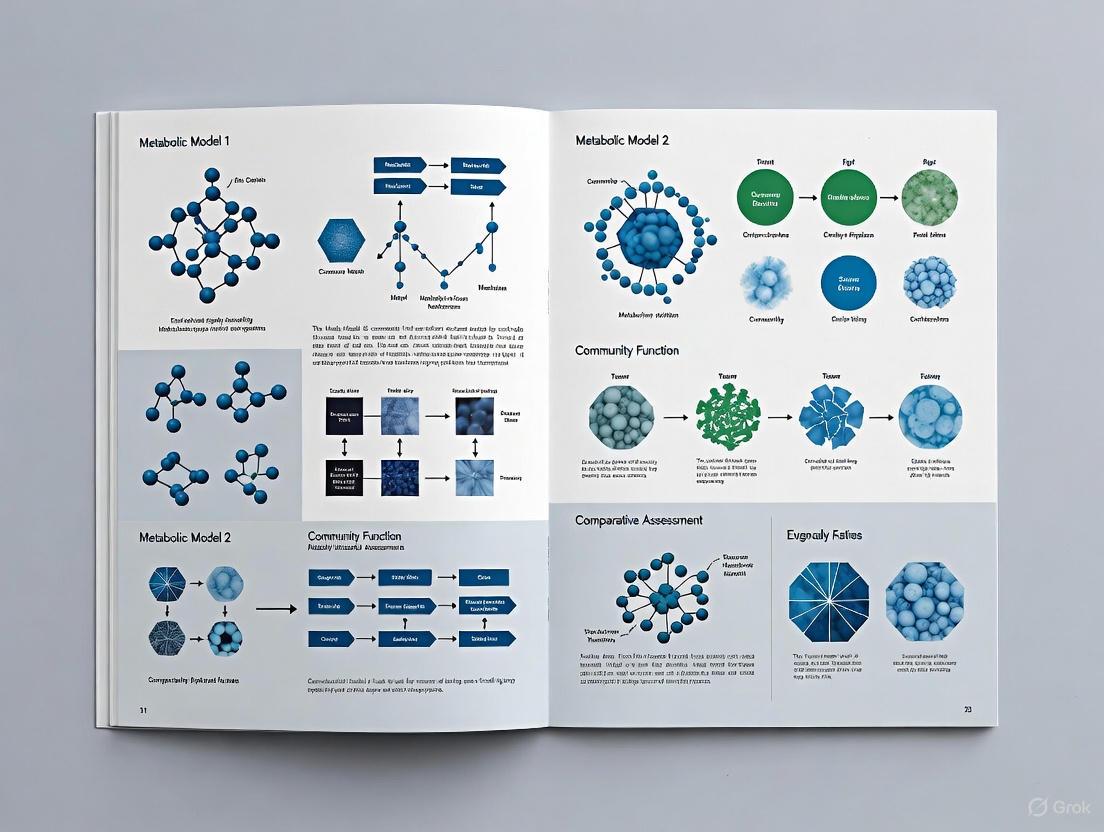

Comparative Assessment of Metabolic Models for Microbial Community Function: From Reconstruction Tools to Biomedical Applications

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become indispensable tools for understanding microbial community functions and their implications in human health and biotechnology.

Comparative Assessment of Metabolic Models for Microbial Community Function: From Reconstruction Tools to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become indispensable tools for understanding microbial community functions and their implications in human health and biotechnology. This article provides a comprehensive comparative assessment of current metabolic modeling approaches for studying community-level metabolism. We explore foundational principles of GEM reconstruction, evaluate automated tools (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) and consensus methods that address database-driven variability. The analysis covers methodological applications in synthetic ecology and host-microbiome interactions, alongside optimization strategies to overcome computational and predictive challenges. Through systematic validation approaches, we demonstrate how metabolic models reveal disease mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease and enable therapeutic discovery. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights for selecting, implementing, and advancing metabolic modeling approaches to decode complex microbial community functions.

Foundations of Microbial Community Metabolic Modeling: Principles, Tools, and Structural Variations

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that mathematically represent the metabolic network of an organism, integrating gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for nearly all metabolic genes [1]. For microbial communities, GEMs provide valuable insights into the functional capabilities of member species and facilitate the exploration of complex microbial interactions that play crucial roles in maintaining microbial diversity, influencing metabolic phenotypes, and shaping community functionality [2]. These models enable researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes—the rates of mass conversion through individual metabolic reactions—which represent the flow of mass through the metabolic network and provide quantitative estimates of metabolites consumed and produced by organisms in a given environment [3].

The application of GEMs has expanded significantly from single-organism models to community-level simulations, enabling the study of metabolic interactions in various environments including the human gut, soils, and industrial bioreactors [2] [4]. This transition reflects the growing recognition that microbial consortia drive essential processes ranging from nitrogen fixation in soils to providing metabolic breakdown products to animal hosts [3]. Community-scale metabolic modeling now serves as a powerful tool for deciphering and designing microbial communities, with applications in agriculture, synthetic biology, pathology, and ecology [2] [4].

Comparative Analysis of GEM Reconstruction Tools

Different automated approaches are available for GEM reconstruction, each with distinct features and underlying databases that significantly impact the resulting models [2]. The major tools include:

- CarveMe: Utilizes a top-down strategy that reconstructs models based on a well-curated, universal template, carving reactions with annotated sequences for fast model generation [2].

- gapseq: Employs a bottom-up approach that constructs draft models through mapping reactions based on annotated genomic sequences, incorporating comprehensive biochemical information from various data sources [2].

- KBase: Implements another bottom-up reconstruction approach using the ModelSEED database, generating immediately functional models suitable for constraint-based modeling [2].

- Consensus Approaches: Combine reconstructed models from multiple tools to integrate their strengths and reduce individual tool-specific biases [2].

Structural and Functional Comparison

A comparative analysis of community models reconstructed from the same metagenomics data revealed significant structural differences depending on the reconstruction approach [2]. The table below summarizes the key structural characteristics observed in models of marine bacterial communities:

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Dead-End Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| gapseq | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Consensus | High | High | High | Lowest |

The analysis further revealed that despite being reconstructed from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), different reconstruction approaches yielded markedly different results with relatively low similarity between respective sets of reactions, metabolites, and genes [2]. Specifically, the Jaccard similarity for reactions between gapseq and KBase models was approximately 0.23-0.24, while similarity for metabolites was approximately 0.37 for models of both coral-associated and seawater bacterial communities [2]. This higher similarity between gapseq and KBase models may be attributed to their shared usage of the ModelSEED database for reconstruction [2].

Impact on Predicted Metabolic Interactions

A critical finding from comparative studies is that the set of exchanged metabolites in community models is more influenced by the reconstruction approach rather than the specific bacterial community investigated [2]. This observation suggests a potential bias in predicting metabolite interactions using community GEMs, as the tool selection alone can significantly impact the predicted metabolic exchanges between community members independent of the actual biological system being modeled [2].

Consensus models have demonstrated advantages in addressing some limitations of individual reconstruction tools. They encompass a larger number of reactions and metabolites while concurrently reducing the presence of dead-end metabolites [2]. By integrating models from multiple tools, consensus approaches retain the majority of unique reactions and metabolites from the original models while incorporating a greater number of genes, indicating stronger genomic evidence support for the reactions [2].

Experimental Protocols for GEM Comparison

Standardized Model Reconstruction Workflow

The experimental methodology for comparative analysis of GEM tools follows a systematic workflow:

Genome Input: High-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) or isolate genomes serve as the standardized input for all reconstruction tools [2].

Parallel Reconstruction: Each automated tool (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) processes the same genomic input to generate draft metabolic models using their respective algorithms and reference databases [2].

Model Integration: For consensus approaches, draft models originating from the same MAG are merged using specialized pipelines such as the recently proposed method that was tested with data from species-resolved operational taxonomic units [2].

Gap-Filling: Community model gap-filling is performed using tools like COMMIT, which employs an iterative approach based on MAG abundance to specify the order of inclusion of MAGs in the gap-filling step [2].

Validation: The resulting models are compared using multiple metrics including number of reactions, metabolites, dead-end metabolites, genes, and functional capabilities [2].

Assessment Metrics and Validation Methods

The comparative evaluation of GEM reconstruction tools employs multiple assessment dimensions:

- Structural Metrics: Quantitative comparison of model elements including genes, reactions, metabolites, and dead-end metabolites [2].

- Similarity Analysis: Jaccard similarity calculations for sets of reactions, metabolites, and genes to measure overlap between tools [2].

- Functional Assessment: Evaluation of metabolic capabilities and exchange metabolites under different environmental conditions [2].

- Iterative Order Impact: Analysis of whether the order of MAG processing during gap-filling significantly influences the resulting solutions [2].

Studies have investigated whether iterative order during gap-filling impacts the resulting network by analyzing the association between MAG abundance and gap-filling solutions [2]. Results demonstrated that the iterative order did not have a significant influence on the number of added reactions, with only a negligible correlation (r = 0-0.3) between the number of added reactions and abundance of MAGs [2].

Metabolic Modeling Approaches for Microbial Communities

Framework for Community-Scale Metabolic Models

Transitioning from single-taxon metabolic models to multitaxon models presents unique challenges that go beyond the mere increase in complexity due to larger numbers of metabolic reactions and metabolites [3]. In microbial community-scale metabolic models, individual taxon-specific metabolic models are embedded in their own compartments within a large extracellular compartment that contains all the taxa [3]. The fundamental mathematical representation employs a stoichiometric matrix (S) that describes all reactions present in the system, with the temporal change in metabolite abundances dictated by a metabolic flux vector through the equation:

[ \frac{d\vec{x}(t)}{dt} = S \cdot \vec{v}(\vec{x}) ]

Under steady-state assumptions, this simplifies to:

[ S \cdot \vec{v} = 0 ]

where (\vec{v}) represents the metabolic flux vector [3].

Key Challenges in Community Modeling

Several significant challenges emerge when modeling microbial communities:

Flux Scaling: Fluxes and flux bounds are usually expressed relative to the dry weight of a given organism, which becomes less well-defined in microbial communities where taxa are present in different relative abundances [3]. This requires careful scaling of exchanges between taxa and the extracellular compartment to maintain mass balance [3].

Objective Function Specification: While single-organism models often maximize growth rate, it is unclear what constitutes maximum fitness in a microbial community [3]. The community growth rate μc is given by the sum of individual growth rates scaled by relative abundance:

[ \muc = \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{ai}{ac} \mu_i ]

where (ai) represents the abundance of taxon i and (ac) the total community abundance [3]. However, there is no evolutionary justification for why unrelated microbial taxa would be driven to maximize overall community biomass [3].

Solution Space Definition: Unlike single organisms where near-maximal growth appears to be a realistic objective, stable microbial consortia show a trade-off (α) representing the fraction of maximum community growth that is actually achieved, lying in a suboptimal region proximal to the maximal community growth plane [3].

Reconstruction Tools and Databases

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Reconstruction Tool | Top-down approach, universal template, fast model generation | High-throughput model reconstruction [2] |

| gapseq | Reconstruction Tool | Bottom-up approach, comprehensive biochemical data sources | Detailed metabolic network reconstruction [2] |

| KBase | Reconstruction Platform | Integrated environment, ModelSEED database | End-to-end analysis from genomes to models [2] |

| COMMIT | Gap-Filling Tool | Iterative gap-filling, abundance-based processing | Community model refinement and completion [2] |

| AGORA2 | Reference Resource | Curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes | Host-microbiome interaction studies [5] |

| ModelSEED | Biochemical Database | Consistent reaction namespace, metabolic mappings | Standardized model reconstruction [2] |

Model Evaluation and Analysis Framework

The experimental framework for GEM comparison requires standardized evaluation protocols:

- Reference Gene Sets: Curated lists of essential genes for benchmarking model performance [6].

- Standardized Media Conditions: Defined nutrient availability for consistent phenotype simulation across tools [6].

- Multiple Biomass Definitions: Variation of objective functions to assess model robustness [6].

- Similarity Metrics: Quantitative measures like Jaccard similarity to compare model components [2].

Previous comparative studies have revealed that predictive ability for single-gene essentiality does not correlate well with predictive ability for synthetic lethal gene interactions (R = 0.159), highlighting the importance of multiple assessment metrics [6]. Furthermore, changes in model scope reflect a history of iterative reconstruction development via collaboration between groups, with each model containing evidence of its history and derivation [6].

The comparative assessment of genome-scale metabolic modeling tools for microbial communities reveals that reconstruction approaches, while based on the same genomes, result in GEMs with varying numbers of genes and reactions as well as metabolic functionalities, primarily attributed to the different databases and algorithms employed [2]. This tool-dependent variability necessitates careful consideration when selecting reconstruction approaches for specific research applications.

Future directions in the field include the development of more sophisticated consensus approaches that retain the majority of unique reactions and metabolites from individual tools while reducing dead-end metabolites [2]. Additionally, integration of GEMs with other modeling frameworks such as quorum sensing mechanisms, microbial ecology interactions, machine learning algorithms, and automated modeling pipelines will further enhance their predictive capabilities and applications [4]. As the field evolves, standardization of reconstruction protocols and validation benchmarks will be crucial for advancing our understanding of microbial community metabolism and its applications across biomedical, environmental, and biotechnological domains.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, enabling the prediction of physiological traits and metabolic capabilities from genomic data. The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs is a critical step for studying microbial ecology, host-microbe interactions, and for applications in biotechnology and drug development [7]. Automated reconstruction tools have been developed to efficiently generate these models from genome sequences. This guide provides a comparative assessment of three prominent tools—CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—focusing on their performance, underlying methodologies, and suitability for investigating microbial community functions.

The selected tools employ distinct reconstruction philosophies and databases, which significantly influence the structure and predictive capacity of the resulting models.

- CarveMe: Utilizes a top-down approach, starting with a universal, curated template model and "carving out" a species-specific model by removing reactions without genomic evidence [8]. It relies on the BiGG database and is designed for speed, producing ready-to-use models for flux balance analysis (FBA) [8] [9].

- gapseq: Employs a bottom-up approach, constructing draft models by mapping annotated genomic sequences to a comprehensive, manually curated biochemical database [8] [10]. It features a novel gap-filling algorithm that incorporates network topology and sequence homology to resolve pathway gaps, aiming for high accuracy and reduced media-specific bias [10].

- KBase (ModelSEED): Also a bottom-up tool, integrated into the web-based KBase platform. It constructs models using the ModelSEED biochemistry database and employs automated gap-filling to enable biomass production on a specified medium [8] [11].

The fundamental methodological differences are summarized in the following workflow diagram.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Model Structure and Content

A comparative analysis of models reconstructed from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) revealed significant structural differences attributed to the underlying databases and algorithms [8].

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Community Metabolic Models Reconstructed from 105 Marine Bacterial MAGs

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Dead-End Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| gapseq | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Consensus | High | High | High | Lowest |

The data indicates that gapseq models contain the most reactions and metabolites, suggesting comprehensive network coverage, but also the highest number of dead-end metabolites, which can indicate network gaps [8]. CarveMe models incorporate the most genes, while KBase models often fall in an intermediate range for these metrics [8].

Predictive Accuracy

Benchmarking against experimental data is crucial for evaluating model quality. Performance varies significantly across tools and data types.

Table 2: Predictive Performance Against Experimental Datasets

| Experimental Validation | gapseq | CarveMe | ModelSEED/KBase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity (True Positive Rate) | 53% | 27% | 30% |

| Enzyme Activity (False Negative Rate) | 6% | 32% | 28% |

| Carbon Source Utilization | Superior | Intermediate | Lower |

| Gene Essentiality Predictions | High Accuracy | Lower | Lower |

| Community Metabolite Cross-Feeding | Accurate | Less Accurate | Less Accurate |

gapseq demonstrates superior performance in predicting enzyme activities and carbon source utilization, showing a significantly higher true positive rate and lower false negative rate compared to CarveMe and ModelSEED/KBase [10]. Its informed gap-filling strategy also leads to more accurate predictions of fermentation products and metabolic interactions within microbial communities [10].

Computational Performance and Usability

Practical considerations like speed and accessibility are important for large-scale studies.

Table 3: Computational and Practical Characteristics

| Characteristic | CarveMe | gapseq | KBase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Speed | Fastest (~20-30 sec/model) | Slowest (~5.5 hours/model) | Intermediate (~3 min/model) |

| Interface | Command Line | Command Line | Web Platform |

| Solver Dependency | CPLEX (Academic) | Open | Open |

| Database Maintenance | Not actively maintained [9] | Actively maintained | Actively maintained |

| High-Throughput Suitability | Excellent | Poor | Limited |

CarveMe is the fastest tool, making it suitable for high-throughput studies involving hundreds to thousands of genomes [9]. In contrast, gapseq's reconstruction process is computationally intensive, taking hours per model, which limits its scalability [9]. KBase provides a user-friendly web interface but is less suited for high-throughput automated workflows [9].

Experimental Protocols for Tool Validation

To ensure reliable and reproducible GEM reconstruction, researchers should follow standardized validation protocols. The methodologies below are synthesized from comparative studies cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Validation of Enzyme Activity and Carbon Source Utilization

Objective: To assess the model's accuracy in predicting core metabolic capabilities.

- Model Reconstruction: Generate GEMs for a set of reference organisms with available phenotypic data using each tool (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase).

- Simulation Conditions: For carbon source utilization, define a minimal medium in the model and systematically allow each carbon source of interest to be the sole carbon input. For enzyme activity, verify the presence of the reaction associated with a specific EC number in the model network.

- Growth Prediction: Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to simulate growth on each carbon source. A growth rate above a defined threshold (e.g., >0.0001 h⁻¹) is predicted as positive.

- Data Comparison: Compare predictions against experimental data from resources like the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase (BacDive) or Phenotype Microarray (Biolog) systems. Calculate accuracy, precision, true positive, and false negative rates [10].

Protocol 2: Assessing Community Model Metabolite Exchange

Objective: To evaluate the tool's performance in predicting metabolic interactions in a community context.

- Community Model Building: Reconstruct GEMs for all members of a defined microbial community (e.g., from MAGs) using the tools under comparison.

- Model Integration: Build a community metabolic model using a compartmentalization approach, where each species' model is placed in a distinct compartment linked via a shared extracellular space.

- Simulation of Interactions: Use a method like costless secretion or dynamic FBA to simulate community metabolism. The medium is dynamically updated based on metabolites secreted by one organism and taken up by another.

- Analysis: Identify the set of predicted exchanged metabolites. Compare these predictions against experimentally measured exometabolomics data or the literature to assess the biological realism of the predicted interactions [8].

Table 4: Key Resources for Metabolic Reconstruction and Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [9] | Software Library | A Python toolbox for simulating and analyzing constraint-based metabolic models. |

| BiGG Models [9] | Knowledgebase | A repository of curated, genome-scale metabolic models using standardized nomenclature. |

| BacDive [10] | Database | Provides experimental data on bacterial phenotypes, used for model validation. |

| AGORA2 [11] | Model Resource | A collection of 7,302 manually curated metabolic reconstructions of human gut microbes. |

| MEMOTE [9] | Software Tool | A community-developed tool for standardized quality control of genome-scale metabolic models. |

| COMMIT [8] | Algorithm | A gap-filling tool designed specifically for microbial community metabolic models. |

The choice between CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase involves a direct trade-off between speed, accuracy, and comprehensiveness.

- Choose CarveMe when your priority is the rapid generation of models for large-scale genomic datasets, such as in population-wide studies, and when a top-down, computationally efficient approach is acceptable [8] [9].

- Choose gapseq when predictive accuracy is the paramount concern, such as for detailed mechanistic studies of organism metabolism or when predicting specific metabolic interactions in communities. Its superior performance in validating against enzymatic and growth data justifies its higher computational cost for smaller-scale studies [10] [12].

- Choose KBase if you prefer a user-friendly web interface and an integrated systems biology platform for analysis, particularly if you are less experienced with command-line tools and are not working with thousands of genomes [11] [9].

For the most reliable assessment of microbial community function, the emerging best practice is to leverage consensus models that integrate reconstructions from multiple tools. This approach has been shown to encompass a larger number of reactions while reducing network gaps, thereby mitigating the individual biases of each tool and providing a more unbiased view of the community's metabolic potential [8].

Database Dependencies and Their Impact on Model Structure and Predictions

The reconstruction and simulation of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are fundamental to systems biology, enabling the prediction of cellular behavior and microbial community interactions. These models are critically dependent on the underlying biochemical databases that provide the curated metabolic reactions, genes, and metabolites. The choice of database can significantly influence the structure, functionality, and predictive outcomes of the resulting models, introducing a source of variability that must be carefully managed. This guide provides a comparative assessment of how different database resources and automated reconstruction tools impact GEM characteristics, with a specific focus on applications in microbial community function research. We synthesize current experimental evidence to objectively compare performance across alternatives, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the data needed to select appropriate resources for their modeling objectives.

Database Landscape and Reconstruction Tool Ecosystem

Major Biochemical Databases

Biochemical databases serve as the foundational knowledge bases for metabolic model reconstruction. Two of the most comprehensive databases are MetaCyc and KEGG, which differ significantly in content and structure. A systematic comparison reveals that KEGG contains approximately 16,586 compounds versus 11,991 in MetaCyc, whereas MetaCyc contains significantly more reactions (10,262 vs. 8,692) and pathways (1,846 base pathways vs. 179 module pathways) [13]. This fundamental difference in content emphasis directly influences the models built upon these resources.

MetaCyc employs a more granular pathway conceptualization with smaller, more biochemically accurate pathway definitions, while KEGG pathways contain 3.3 times as many reactions on average [13]. Additionally, MetaCyc includes broader taxonomic range annotations and relationships from compounds to enzymes that regulate them, attributes largely absent from KEGG. These structural differences propagate to the models generated from these databases, affecting their biological interpretability and simulation characteristics.

Automated Reconstruction Tools and Their Database Dependencies

Several automated tools leverage these databases to convert genomic information into functional metabolic models. Three widely used tools—CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—employ distinct databases and reconstruction philosophies, resulting in models with different structural and functional properties [2].

- CarveMe utilizes a top-down approach, starting with a universal model template and carving it down based on genomic evidence, primarily using the BiGG database [2].

- gapseq implements a bottom-up approach, building models from annotated genomic sequences by drawing comprehensive biochemical information from various sources, including ModelSEED [2].

- KBase also employs a bottom-up strategy, constructing models using the ModelSEED database for reaction mapping [2].

The database dependencies of these tools directly impact their output. Models reconstructed from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using different tools exhibit markedly different gene, reaction, and metabolite counts, leading to variations in functional predictions [2].

Table 1: Database Dependencies of Major Reconstruction Tools

| Tool | Reconstruction Approach | Primary Database Dependencies | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Top-down | BiGG | Uses a universal template; faster model generation [2] |

| gapseq | Bottom-up | ModelSEED, various sources | Comprehensive biochemical information; more reactions and metabolites [2] |

| KBase | Bottom-up | ModelSEED | ModelSEED reaction mapping; higher gene similarity to CarveMe [2] |

Comparative Analysis of Model Structure and Predictions

Structural Variations in Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Experimental comparisons of GEMs reconstructed from the same set of 105 high-quality MAGs using CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase reveal significant structural differences attributable to their database dependencies [2].

Table 2: Structural Characteristics of Community Models from Different Reconstruction Tools (Adapted from [2])

| Model Characteristic | CarveMe | gapseq | KBase | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Genes | Highest | Lower | Intermediate | High (majority from CarveMe) |

| Number of Reactions | Lower | Highest | Intermediate | Highest (retains unique reactions) |

| Number of Metabolites | Lower | Highest | Intermediate | Highest |

| Number of Dead-End Metabolites | Lower | Higher | Intermediate | Reduced |

| Jaccard Similarity (Reactions) | Low (vs. gapseq/KBase) | Medium (vs. KBase) | Medium (vs. gapseq) | High (vs. CarveMe) |

The structural analysis indicates that gapseq models typically encompass more reactions and metabolites, while CarveMe models include the highest number of genes [2]. However, gapseq models also exhibit a larger number of dead-end metabolites, which can potentially affect metabolic functionality. The low Jaccard similarity coefficients for reactions, metabolites, and genes between models reconstructed from the same MAGs using different tools highlight the significant variability introduced by the database and tool selection [2].

Impact on Predicted Metabolic Interactions

The choice of reconstruction approach and its underlying database significantly influences the prediction of metabolite exchanges within microbial communities, a critical aspect of community function research. Studies have demonstrated that the set of exchanged metabolites is more strongly influenced by the reconstruction approach itself than by the specific bacterial community being investigated [2]. This suggests a potential bias in predicting metabolite interactions using community GEMs, which researchers must account for when interpreting simulation results.

For instance, consensus models that integrate reconstructions from multiple tools demonstrate the ability to reduce the presence of dead-end metabolites while encompassing a larger number of reactions and metabolites [2]. This integrated approach leverages the strengths of different databases, creating more comprehensive and functionally complete network models for studying community interactions.

Experimental Protocols for Model Comparison

Workflow for Comparative Model Reconstruction and Analysis

To systematically evaluate the impact of databases on model structure and predictions, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol, derived from comparative studies [2]:

- Input Data Preparation: Collect high-quality MAGs or genome sequences for the microbial community of interest.

- Parallel Model Reconstruction:

- Process the same set of MAGs through multiple automated reconstruction tools (e.g., CarveMe, gapseq, KBase).

- Use default settings for each tool to reflect their standard database dependencies.

- Draft Consensus Model Generation:

- Merge draft models originating from the same MAG that were generated by the different tools.

- Use a consensus pipeline to integrate the models, taking the union of metabolic capabilities.

- Gap-Filling:

- Perform gap-filling on the draft community models using a tool like COMMIT.

- Employ an iterative approach based on MAG abundance, starting with a minimal medium and dynamically updating it with permeable metabolites identified in each step.

- Structural Comparison:

- Extract and quantify the number of reactions, metabolites, dead-end metabolites, and genes from each resulting reconstruction.

- Compute Jaccard similarity coefficients for these sets between models derived from the same MAGs via different approaches.

- Functional Analysis:

- Simulate metabolic interactions, such as metabolite exchange fluxes, under defined conditions.

- Compare the predicted interaction profiles across the different model sets.

Protocol for Assessing Iterative Gap-Filling

A specific methodological consideration in community modeling is whether the order of processing MAGs during gap-filling influences the final model. The experimental steps to assess this are [2]:

- Define Iterative Orders: Establish both ascending and descending processing orders for MAGs based on their relative abundance in the community.

- Initialize Medium: Start with a chemically defined minimal medium for the initial gap-filling step.

- Iterative Gap-Filling: For each MAG in the specified order:

- Perform gap-filling using the current medium composition.

- Predict permeable metabolites from the gap-filled model.

- Augment the medium by adding these permeable metabolites, making them available for subsequent reconstructions.

- Correlation Analysis: Upon completion, calculate the correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson correlation) between the number of reactions added during gap-filling for each MAG and its abundance rank.

- Result Interpretation: A negligible correlation (e.g., r = 0-0.3) indicates that the iterative order has no significant impact on the gap-filling solution, strengthening the robustness of the consensus approach [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe [2] | Reconstruction Tool | Top-down generation of GEMs from genomes. | Uses universal BiGG template; fast execution. |

| gapseq [2] | Reconstruction Tool | Bottom-up generation of GEMs from genomes. | Comprehensive biochemical data integration. |

| KBase [2] | Reconstruction Platform | Web-based, bottom-up GEM reconstruction and analysis. | Integrated ModelSEED database and analysis apps. |

| COMMIT [2] | Modeling Software | Gap-filling of community metabolic models. | Iterative medium augmentation; context-specific modeling. |

| MetaCyc [13] | Biochemical Database | Curated resource of metabolic pathways and reactions. | Granular, experimentally verified pathways. |

| KEGG [13] | Biochemical Database | Integrated resource for genomic and chemical information. | Broad coverage of compounds and functional modules. |

| BiGG Models [14] | Biochemical Database | Knowledgebase of curated, genome-scale metabolic models. | Standardized namespace for modeling. |

| ModelSEED [15] [2] | Database & Pipeline | Automated reconstruction and analysis of metabolic models. | Core database for gapseq and KBase. |

The dependency of metabolic models on underlying biochemical databases is a fundamental factor determining their structure and predictive power. Evidence consistently shows that the selection of reconstruction tools and their associated databases—such as BiGG for CarveMe and ModelSEED for gapseq and KBase—leads to quantifiable differences in gene content, reaction network complexity, and predicted metabolic interactions. For researchers investigating microbial community functions, the consensus approach emerges as a powerful strategy to mitigate the biases inherent in any single database or tool. By integrating models from multiple sources, consensus building retains a broader set of metabolic functions while reducing network gaps, thereby providing a more robust foundation for generating biological insights and hypotheses in fields ranging from microbial ecology to drug development.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) of microbial communities provide powerful computational frameworks for investigating the functional capabilities of community members and exploring complex microbial interactions [2]. These models are increasingly crucial in diverse fields including agriculture, synthetic biology, human health, and ecology [16]. The reconstruction process for community metabolic models typically employs automated tools that transform genomic information into stoichiometric representations of metabolic networks, enabling constraint-based analysis methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA) [16].

A significant challenge in this field stems from the inherent variability introduced by different reconstruction methodologies. Automated reconstruction tools rely on distinct biochemical databases and algorithms, which can lead to substantially different model structures and functional predictions even when based on identical genomic starting material [2]. This variability introduces uncertainty when drawing biological conclusions from in silico analyses. To address this challenge, consensus reconstruction approaches have emerged that integrate outcomes from multiple reconstruction tools, potentially reducing individual tool-specific biases and creating more comprehensive metabolic networks [2] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Approaches

Structural Differences Across Reconstruction Tools

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Community Models from Different Reconstruction Approaches

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Dead-End Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| gapseq | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Consensus | High | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

Comparative studies utilizing metagenomics data from marine bacterial communities have revealed substantial structural variations between GEMs generated by different automated reconstruction tools [2] [18]. When analyzing models reconstructed from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), significant differences emerged in the numbers of genes, reactions, metabolites, and dead-end metabolites [2]. Specifically, CarveMe models consistently contained the highest number of genes, while gapseq models encompassed more reactions and metabolites than either CarveMe or KBase models [2]. However, this comprehensive coverage in gapseq came with a notable drawback: a higher incidence of dead-end metabolites, which can potentially affect model functionality [2].

The consensus approach to model reconstruction demonstrates distinct advantages in structural metrics. By integrating models from multiple tools, consensus models encompass a larger number of reactions and metabolites while simultaneously reducing the presence of dead-end metabolites [2] [17]. This structural improvement suggests that consensus modeling may provide more complete metabolic network coverage while minimizing gaps in metabolic pathways that lead to dead-end metabolites.

Tool-Specific Characteristics and Database Influences

Table 2: Reconstruction Tool Methodologies and Database Dependencies

| Tool | Reconstruction Approach | Primary Database | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Top-down | Custom template | Fast model generation; ready-to-use networks |

| gapseq | Bottom-up | Multiple sources | Comprehensive biochemical information; many data sources |

| KBase | Bottom-up | ModelSEED | User-friendly platform; immediately functional models |

The structural variations observed across different reconstruction tools stem from fundamental methodological differences. CarveMe employs a top-down strategy, beginning with a well-curated universal template and removing reactions without genomic evidence [2]. In contrast, both gapseq and KBase utilize bottom-up approaches, constructing draft models by mapping reactions based on annotated genomic sequences [2]. These different philosophical approaches to model reconstruction naturally yield networks with distinct properties.

Database dependencies significantly influence the resulting model structures. The relatively higher similarity observed between gapseq and KBase models in terms of reaction and metabolite composition has been attributed to their shared utilization of the ModelSEED database for reconstruction [2]. This database effect underscores how the underlying biochemical knowledge resources can shape model content and subsequent predictions. Interestingly, while CarveMe and KBase show higher similarity in gene composition, the consensus models demonstrate strongest similarity with CarveMe in terms of gene content, suggesting that the majority of genes in consensus models originate from CarveMe reconstructions [2].

Experimental Protocols for Model Comparison

Model Reconstruction and Consensus Building

The experimental workflow for comparative analysis of community metabolic models begins with the acquisition of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) as foundational inputs [2]. These genomic resources serve as the common starting point for all subsequent reconstruction efforts, ensuring that observed differences can be attributed to methodological variations rather than genomic quality or completeness.

The reconstruction phase employs multiple automated tools in parallel. The CarveMe tool utilizes its top-down approach with a universal metabolic template, while gapseq and KBase implement their distinct bottom-up methodologies [2]. Following individual reconstructions, the consensus building process integrates these alternative models using specialized pipelines such as GEMsembler, which systematically combines models from different tools while tracking the origin of metabolic features [17]. This consensus approach aims to harness the unique strengths of each reconstruction method while mitigating individual limitations.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for model reconstruction and consensus building

Gap-Filling and Model Validation

After draft model reconstruction, a critical gap-filling step is performed using tools such as COMMIT, which implements an iterative approach based on MAG abundance [2]. This process begins with a minimal medium definition, and after each model's gap-filling procedure, permeable metabolites are predicted and utilized to augment the medium for subsequent reconstructions. This iterative refinement ensures biological relevance while maintaining consistency across community models.

Experimental analyses have investigated whether the iterative order during gap-filling influences the resulting solutions [2]. Studies revealed that the order of MAG processing had negligible correlation (r = 0-0.3) with the number of added reactions, suggesting that reconstruction outcomes are robust to processing sequence [2]. This finding strengthens confidence in the reproducibility of community model reconstruction across different implementation scenarios.

Model validation represents the final critical phase, where structural and functional assessments are conducted. Structural comparisons examine the numbers of reactions, metabolites, dead-end metabolites, and genes, while functional validations assess predictive accuracy for auxotrophy and gene essentiality [2] [17]. Consensus models have demonstrated superior performance in these validation metrics, particularly in reducing dead-end metabolites and improving prediction of essential genes [17].

Impact on Predicted Community Interactions

Metabolic Interaction Predictions

A crucial finding from comparative studies concerns the significant influence of reconstruction methodology on predicted metabolic interactions. Research has demonstrated that the set of exchanged metabolites in community models is more strongly influenced by the reconstruction approach than by the specific bacterial community being investigated [2]. This suggests a potential bias in predicting metabolite interactions using community GEMs, where methodological artifacts may overshadow biological signals.

The consensus approach appears to mitigate this bias by integrating evidence from multiple reconstruction paradigms. By combining top-down and bottom-up strategies, consensus models leverage the complementary strengths of each approach, potentially yielding more biologically realistic interaction predictions [2]. This integration is particularly valuable for identifying cross-feeding relationships and metabolic dependencies that drive community assembly and stability.

Functional Performance and Biological Relevance

Beyond structural metrics, functional performance represents the ultimate validation of model quality. Comparative assessments have demonstrated that consensus models consistently outperform individual reconstructions in predicting experimentally observed metabolic traits [17]. Specifically, GEMsembler-curated consensus models built from automatically reconstructed models of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Escherichia coli surpassed gold-standard models in auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions [17].

The functional advantages of consensus approaches extend to improved gene-protein-reaction (GPR) association resolution. Optimization of GPR combinations from consensus models has been shown to improve gene essentiality predictions, even in manually curated gold-standard models [17]. This capability to enhance prediction accuracy in well-characterized systems highlights the value of consensus approaches for refining metabolic network annotations and functional assignments.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Community Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Software tool | Top-down model reconstruction using universal template; enables fast model generation |

| gapseq | Software tool | Bottom-up model reconstruction incorporating comprehensive biochemical information |

| KBase | Software platform | Integrated platform for bottom-up model reconstruction and analysis |

| GEMsembler | Software package | Builds consensus models from multiple reconstructions; analyzes model structure/function |

| COMMIT | Software tool | Performs gap-filling of community models using iterative approach |

| ModelSEED | Biochemical database | Curated biochemical repository used by multiple reconstruction tools |

The experimental workflow for comparative analysis of community metabolic models relies on specialized computational tools and resources. The core reconstruction tools—CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—provide the foundational model generation capabilities, each with distinct methodological approaches and database dependencies [2]. These are complemented by specialized tools for consensus building (GEMsembler) and gap-filling (COMMIT) that enhance model completeness and functional accuracy [2] [17].

The GEMsembler package deserves particular note for its comprehensive functionality in comparing cross-tool GEMs, tracking feature origins, and constructing consensus models containing customized subsets of input models [17]. This tool provides specialized analysis capabilities including identification and visualization of biosynthesis pathways, growth assessment, and agreement-based curation workflows that significantly enhance model quality and biological relevance [17].

Comparative analysis of structural variations in community metabolic models reveals significant differences in reactions, metabolites, and dead-end metabolites across reconstruction approaches. These methodological variations substantially impact subsequent biological interpretations, particularly in predicting metabolic interactions and functional capabilities. The consensus modeling approach emerges as a powerful strategy for mitigating individual tool biases, combining complementary strengths to generate more comprehensive and biologically accurate metabolic networks. By systematically integrating evidence from multiple reconstruction paradigms, consensus models enhance structural completeness while reducing metabolic gaps, ultimately advancing our capacity to investigate complex community-level metabolic processes in silico.

In the field of systems biology, top-down and bottom-up approaches represent two fundamentally different philosophies for reconstructing and analyzing complex biological systems. These methodologies are particularly crucial in metabolic modeling, where researchers aim to build computational representations of metabolic networks to predict cellular behavior and function. The top-down approach begins with system-wide 'omics' data and works downward to infer network components and interactions, while the bottom-up approach starts with detailed component knowledge and builds upward to reconstruct entire systems [19] [20]. Both strategies offer distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different research scenarios and objectives.

The comparative assessment of these reconstruction approaches is particularly relevant in the context of metabolic models for community function research, where understanding multi-species interactions is essential for applications in drug development, microbiome research, and biotechnology. As the field advances, researchers are increasingly recognizing that a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both methodologies may offer the most comprehensive path forward for modeling complex biological systems [2]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these foundational approaches, supported by experimental data and practical implementation frameworks.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Differences

Core Principles and Methodologies

The bottom-up approach is characterized by its systematic assembly of biological systems from their fundamental components. This methodology begins with detailed knowledge of individual elements—genes, proteins, and metabolites—and progressively integrates them into larger functional units. In metabolic modeling, this typically involves draft reconstruction based on genomic data, followed by manual curation to ensure biological accuracy, and culminating in network reconstruction through mathematical frameworks [19]. The bottom-up approach heavily relies on existing knowledge databases such as KEGG, MetaCyc, and Reactome to establish gene-protein-reaction rules that form the foundation of constraint-based models [20]. This method is inherently mechanistic, building comprehensive genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) from well-annotated genomic information and biochemical transformations.

In contrast, the top-down approach begins with system-wide observational data and works to identify the underlying network structure. This methodology employs high-throughput 'omics' data—such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—processed with statistical and bioinformatics tools to reverse-engineer the active metabolic network for a specific condition [19] [20]. Rather than building from first principles, top-down approaches infer network architecture from patterns in experimental data, making them particularly valuable for identifying condition-specific biological states. The top-down process can be viewed as a reverse-engineering strategy that extracts information content from metabolome data to discover underlying network structures without a priori knowledge of all components [20].

Conceptual Frameworks and Directionality

The philosophical distinction between these approaches can be visualized through their fundamental directionality of investigation:

This conceptual distinction translates into practical differences in application. Bottom-up approaches are particularly valuable when comprehensive genomic information is available and the goal is to build a mechanistic understanding of system capabilities. These models excel at predicting metabolic fluxes under different conditions and identifying potential engineering targets for metabolic optimization. Top-down approaches, conversely, are most beneficial when studying system responses to specific conditions or perturbations, where the focus is on identifying the actually active network components rather than all possible capabilities [20].

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Approaches

Structural and Functional Comparison

Direct comparison of metabolic models reconstructed through different approaches reveals significant differences in their structural properties and functional capabilities. Recent research analyzing genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) of microbial communities has demonstrated that the choice of reconstruction approach substantially impacts model composition and predictive capabilities [2].

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Metabolic Models from Different Reconstruction Approaches

| Characteristic | Bottom-Up Approach | Top-Down Approach | Consensus Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Genes | Variable (tool-dependent) | Generally lower | Highest (aggregates multiple sources) |

| Number of Reactions | Comprehensive coverage | Condition-specific | Most comprehensive |

| Number of Metabolites | Extensive | Focused on detected compounds | Most extensive |

| Dead-End Metabolites | Tool-dependent | Fewer (data-constrained) | Fewest (gap reduction) |

| Database Dependency | High (KEGG, ModelSEED) | Minimal (data-driven) | Multiple databases |

| Condition Specificity | General (all possible states) | Specific to data conditions | Balanced |

The structural differences between approaches have direct implications for their functional predictions. Studies comparing models reconstructed from the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using different tools revealed surprisingly low Jaccard similarity between the resulting sets of reactions, metabolites, and genes [2]. This indicates that the reconstruction approach itself introduces significant variation in model composition, which subsequently affects predictions about metabolic capabilities and potential microbial interactions.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Experimental validation of reconstruction approaches provides critical insights into their relative strengths and limitations. Comparative studies have evaluated these methodologies across multiple performance dimensions relevant to research and drug development applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Reconstruction Approaches

| Performance Metric | Bottom-Up Approach | Top-Down Approach | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy of Metabolic Flux Predictions | High for known pathways | Conditionally accurate | 13C flux analysis |

| Identification of Exchange Metabolites | Potentially biased by database | Limited by detection | Mass spectrometry |

| Coverage of Metabolic Functions | Comprehensive (all possible) | Context-dependent | Physiological assays |

| Handling of Missing Knowledge | Gap-filling required | Data interpolation | Knockout studies |

| Condition-Specific Relevance | Lower | Higher | Multi-condition culturing |

| Computational Demand | High for simulation | High for data processing | N/A |

A critical finding from comparative analyses is that predictions of exchanged metabolites in community models are more strongly influenced by the reconstruction approach than by the actual biological community being studied [2]. This indicates a significant potential bias in predicting metabolite interactions using community metabolic models, regardless of whether top-down or bottom-up approaches are employed. This has profound implications for drug development targeting microbial communities, where metabolic cross-feeding and interactions may be therapeutic targets.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Bottom-Up Reconstruction Workflow

The bottom-up reconstruction protocol involves multiple systematic steps to build biological networks from component knowledge:

Step 1: Genome Annotation and Draft Reconstruction

- Input: Annotated genome sequence

- Process: Identify metabolic genes and map to biochemical reactions using databases (KEGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED)

- Tools: CarveMe, gapseq, KBase, ModelSEED

- Output: Draft metabolic network containing all possible reactions

Step 2: Manual Curation and Network Refinement

- Input: Draft metabolic network

- Process: Validate reaction presence through literature mining, correct gene-protein-reaction associations, add transport reactions, and define biomass composition

- Validation: Growth simulation under different conditions, comparison with experimental data

- Output: Curated genome-scale metabolic reconstruction

Step 3: Mathematical Model Formulation

- Input: Curated metabolic network

- Process: Convert to stoichiometric matrix, define constraints (enzyme capacity, nutrient availability), implement computational framework (COBRA Toolbox)

- Methods: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA)

- Output: Computational model capable of simulating metabolic states

Step 4: Model Validation and Gap Analysis

- Input: Computational model

- Process: Compare predictions with experimental data, identify dead-end metabolites, perform gap-filling to complete pathways

- Validation: 13C metabolic flux analysis, comparison with cultivability data

- Output: Validated genome-scale metabolic model [19] [20] [2]

Top-Down Reconstruction Protocol

The top-down reconstruction methodology follows a contrasting approach focused on inference from system-wide data:

Step 1: Multi-Omics Data Acquisition

- Input: Biological samples under specific conditions

- Methods: Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq), Proteomics (mass spectrometry), Metabolomics (LC-MS, GC-MS)

- Replication: Multiple biological and technical replicates across conditions

- Output: Quantitative molecular profiling data

Step 2: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Input: Raw omics data

- Process: Quality control, normalization, batch effect correction, missing value imputation

- Statistical Methods: Principal component analysis, clustering, outlier detection

- Output: Cleaned, normalized dataset for analysis

Step 3: Network Inference and Reverse Engineering

- Input: Processed omics data

- Methods: Correlation networks (WGCNA), statistical inference (ARACNe), integration with prior knowledge

- Validation: Network robustness tests, comparison with known pathways

- Output: Condition-specific metabolic network

Step 4: Integration with Structural Databases

- Input: Inferred network

- Process: Map components to biochemical databases, identify complete pathways, contextualize with existing knowledge

- Tools: Metabolite enrichment analysis, pathway mapping algorithms

- Output: Functional interpretation of inferred network [20]

The experimental workflow for both approaches can be visualized as follows:

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of reconstruction approaches requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key solutions used in metabolic modeling and systems biology research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Reconstruction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Approach | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Software Tool | Automated model reconstruction from genomes | Top-down based on universal template | High-throughput model building |

| gapseq | Software Tool | Biochemical reaction mapping from genomic sequences | Bottom-up | Customized metabolic reconstruction |

| KBase | Platform | Integrated bioinformatics and modeling | Bottom-up | Multi-omics data integration |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB Suite | Constraint-based modeling and simulation | Both | Metabolic flux analysis |

| MetaCyc | Database | Curated metabolic pathway database | Both | Reaction and pathway reference |

| KEGG | Database | Integrated pathway mapping resource | Both | Genomic and chemical data |

| COMMIT | Software Tool | Community metabolic model gap-filling | Both | Microbial community modeling |

| ModelSEED | Platform | Automated model reconstruction and analysis | Primarily bottom-up | Genome-scale model building |

The selection of appropriate tools significantly influences reconstruction outcomes. Comparative studies have demonstrated that tools using different biochemical databases produce models with varying metabolic functionalities, even when starting from the same genomic information [2]. This database dependency introduces uncertainty in predictions and highlights the importance of tool selection based on research objectives.

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The comparative assessment of top-down and bottom-up approaches has significant implications for pharmaceutical research and therapeutic development. Each methodology offers distinct advantages for different stages of the drug discovery pipeline.

For target identification, bottom-up approaches provide comprehensive mapping of potential metabolic interventions, while top-down methods can identify condition-specific vulnerabilities in pathological states. In microbiome-related therapeutics, consensus approaches that combine multiple reconstruction methods have demonstrated superior performance in capturing community-level metabolic interactions that may serve as therapeutic targets [2].

The integration of both approaches presents a promising path forward for metabolic modeling in drug development. Hybrid frameworks leverage the comprehensive coverage of bottom-up reconstruction with the condition relevance of top-down inference, potentially offering more accurate predictions of metabolic behavior in health and disease states. This is particularly valuable for modeling drug metabolism, identifying mechanism-based toxicity, and understanding the metabolic consequences of therapeutic interventions.

As the field advances, improvements in automated reconstruction, quality control protocols, and consensus-building methodologies will further enhance the reliability of metabolic models for pharmaceutical applications. The continuing development of these computational approaches promises to accelerate drug discovery and improve success rates in clinical development through more accurate prediction of metabolic effects.

The Emergence of Consensus Models for Enhanced Functional Coverage

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are pivotal computational tools in systems biology, enabling researchers to investigate cellular metabolism and predict phenotypic responses to genetic and environmental perturbations [17]. These models integrate genomic information with biochemical knowledge to reconstruct metabolic networks, providing a platform for simulating metabolic fluxes using methods such as flux balance analysis [21]. However, a significant challenge arises from the fact that different automated reconstruction tools—such as CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—generate GEMs with substantially different structural and functional properties, even when starting from the same genomic data [2]. This variability stems from their reliance on different biochemical databases, reconstruction algorithms, and template networks, leading to inconsistent predictions and highlighting gaps in our metabolic knowledge [17] [2].

Consensus genome-scale metabolic models represent an emerging approach to address these limitations. Rather than relying on a single reconstruction method, consensus models integrate multiple GEMs reconstructed for the same organism using different tools, synthesizing their collective metabolic capabilities into a unified network [17] [2]. This methodology harnesses the unique strengths of each reconstruction approach while mitigating individual weaknesses, effectively creating metabolic networks with enhanced functional coverage and predictive accuracy. The resulting models capture a more comprehensive view of an organism's metabolic potential, combining genomic evidence from multiple sources to reduce reconstruction bias and improve biological relevance [17]. For microbial communities, where metabolic interactions play crucial roles in maintaining diversity and shaping community functionality, consensus approaches offer particular promise for more accurately predicting metabolic exchanges and community-level metabolic phenotypes [2].

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Approaches

Structural and Functional Variations Across Tools

Automated reconstruction tools employ distinct methodologies that significantly impact the structural and functional properties of the resulting GEMs. CarveMe utilizes a top-down approach, starting with a universal template model and carving out reactions based on genomic evidence, enabling rapid model generation [2]. In contrast, gapseq and KBase employ bottom-up strategies, constructing models by mapping annotated genomic sequences to biochemical reactions, with gapseq incorporating particularly comprehensive biochemical information from diverse data sources [2]. These methodological differences translate into substantial variations in model content and predictive capabilities, as evidenced by comparative studies using metagenomics data from marine bacterial communities [2].

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of GEMs Reconstructed Using Different Approaches for Marine Bacterial Communities

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Dead-end Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| gapseq | Intermediate | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Consensus | High | High | High | Lowest |

The structural differences highlighted in Table 1 have direct implications for functional predictions. While gapseq models encompass the largest number of reactions and metabolites, they also contain the most dead-end metabolites—metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed due to network gaps—which potentially compromises metabolic functionality [2]. Consensus models effectively balance these trade-offs, incorporating a comprehensive set of reactions and metabolites while simultaneously reducing dead-end metabolites through network complementation [2].

Quantitative Performance Assessment

The ultimate value of metabolic models lies in their ability to accurately predict biological phenotypes. Comparative studies have demonstrated that consensus models consistently outperform individual reconstructions and even manually curated gold-standard models in key functional predictions [17]. When evaluated using established benchmarks such as auxotrophy (nutrient requirement) predictions and gene essentiality screens, consensus models exhibit superior agreement with experimental observations across multiple bacterial species [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GEM Types for Functional Predictions

| Model Type | Auxotrophy Prediction Accuracy | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | Functional Coverage | Network Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Intermediate | Intermediate | Moderate | Moderate |

| gapseq | Varies | Varies | High | Low to Moderate |

| KBase | Intermediate | Intermediate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gold-Standard (Manual) | High | High | High | High |

| Consensus | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

Notably, consensus models not only outperform automatically reconstructed individual models but also show improved performance compared to manually curated gold-standard models for specific prediction tasks [17]. This performance advantage stems from the consensus approach's ability to integrate complementary metabolic knowledge from multiple sources, effectively capturing a more complete representation of an organism's metabolic capabilities. Additionally, optimizing gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations within consensus models further enhances gene essentiality predictions, highlighting how this approach can inform even expert manual curation [17].

Methodological Framework for Consensus Modeling

GEMsembler: A Computational Platform for Consensus Assembly

The GEMsembler Python package represents a specialized computational framework designed specifically for consensus metabolic model assembly and analysis [17]. This tool provides comprehensive functionality for comparing cross-tool GEMs, tracking the origin of model components, and constructing consensus models containing user-specified subsets of input models [17]. The package implements an agreement-based curation workflow that systematically identifies and resolves inconsistencies between input models while preserving their complementary strengths.

GEMsembler operates through a multi-stage process that includes: (1) standardized loading and normalization of input GEMs from different reconstruction tools; (2) systematic comparison of model structures, including reactions, metabolites, genes, and pathway organizations; (3) identification of consensus and unique elements across models; (4) configurable assembly of consensus models based on user-defined rules for component inclusion; and (5) integrated analysis capabilities for evaluating model performance and uncertainty [17]. This structured approach enables researchers to generate consensus models that effectively harness the metabolic information distributed across multiple reconstructions.

Consensus Model Construction for Microbial Communities

For microbial communities, consensus modeling adopts a more complex workflow to account for interspecies interactions and community-level metabolic functions. The process involves generating individual consensus models for each species or metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) before integrating them into a community metabolic model [2]. This approach has been successfully applied to marine bacterial communities, demonstrating its value for elucidating community-level metabolic interactions and functional capabilities [2].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for constructing consensus metabolic models for microbial communities:

A critical consideration in community metabolic modeling is the potential influence of iterative gap-filling order on the resulting network structure. Studies have investigated whether the sequence in which individual models are incorporated affects gap-filling solutions, particularly when using tools like COMMIT for community model integration [2]. Reassuringly, empirical analyses reveal that the iterative order has minimal impact on the number of added reactions, with only negligible correlations (r = 0-0.3) observed between model abundance and gap-filling extent [2]. This finding supports the robustness of consensus approaches for community metabolic modeling.

Experimental Validation and Applications

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Rigorous validation is essential to establish the predictive accuracy and biological relevance of consensus metabolic models. The following experimental protocols represent standardized approaches for benchmarking model performance:

4.1.1 Auxotrophy Prediction Assays Auxotrophy predictions evaluate a model's ability to correctly identify essential nutrients that an organism cannot synthesize. Validation involves cultivating the target organism in chemically defined media with systematic nutrient omissions and measuring growth phenotypes [21]. For example, Streptococcus suis validation experiments utilized a complete chemically defined medium (CDM) containing glucose, amino acids, nucleotides, vitamins, and ions, with growth rates measured optically at 600 nm after 15 hours of cultivation [21]. The model prediction is considered accurate if it correctly identifies impaired growth in omitted-nutrient conditions that the organism requires.

4.1.2 Gene Essentiality Screens Gene essentiality assessments compare model predictions with empirical data from mutant libraries. Computational simulations involve sequentially constraining the flux through reactions catalyzed by each gene to zero and evaluating the impact on biomass production [17] [21]. A gene is predicted as essential if its knockout reduces the growth rate below a threshold (typically <1% of wild-type). Experimental validation employs transposon mutagenesis or CRISPR-based approaches to generate mutant libraries, with essential genes identified through statistical analysis of insertion frequencies or growth deficits [17].

4.1.3 Quantitative Growth Phenotyping Comprehensive growth profiling under multiple nutrient conditions provides additional validation. This involves cultivating organisms in different carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus sources while measuring growth kinetics [21]. Model predictions are generated through flux balance analysis by constraining uptake reactions to available nutrients and comparing simulated growth rates with experimental measurements. Correlation between predicted and observed growth phenotypes across conditions indicates model accuracy.

Application Case Studies

Consensus metabolic models have demonstrated significant utility across multiple biological domains:

4.2.1 Microbial Community Ecology In marine bacterial communities derived from coral-associated and seawater environments, consensus models revealed structural and functional differences that were obscured in individual reconstructions [2]. These models successfully identified conserved and variable metabolic functions across communities, elucidating how evolutionary history and ecological niche shape metabolic capabilities. The consensus approach proved particularly valuable for predicting metabolic interactions and exchanged metabolites within communities, although researchers noted a potential reconstruction-method bias that must be considered in interaction predictions [2].

4.2.2 Pathogen Metabolism and Virulence For pathogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus suis, metabolic models have identified critical connections between metabolic capabilities and virulence mechanisms [21]. Through consensus approaches, researchers identified 131 virulence-linked genes, 79 of which participated in 167 metabolic reactions within the S. suis model [21]. Importantly, 26 genes were found to be essential for both growth and virulence factor production, highlighting potential dual-function drug targets, particularly in capsular polysaccharide and peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathways [21].

4.2.3 Metabolic Engineering and Biotechnology Consensus models provide robust platforms for metabolic engineering applications by offering more complete and accurate representations of metabolic networks. The enhanced functional coverage enables better prediction of engineering outcomes, including gene knockout effects, heterologous pathway integration, and substrate utilization optimization. The improved gene essentiality predictions from consensus models directly inform genetic engineering strategies by more reliably identifying non-essential genes suitable as insertion sites and essential genes to avoid modifying.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows supporting consensus metabolic modeling rely on specialized reagents, computational tools, and databases. The following table details essential resources for implementing these approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Consensus Metabolic Modeling

| Category | Resource | Description | Application in Consensus Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | GEMsembler | Python package for consensus model assembly | Core platform for comparing GEMs and building consensus models [17] |

| CarveMe | Top-down automated reconstruction tool | Input model generation for consensus building [2] | |

| gapseq | Bottom-up automated reconstruction tool | Input model generation with comprehensive biochemical data [2] | |

| KBase | Web-based reconstruction and analysis platform | Input model generation and community modeling [2] | |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package for constraint-based modeling | Model simulation, gap-filling, and validation [21] | |

| Biochemical Databases | ModelSEED | Biochemical database and reconstruction platform | Standardized biochemical namespace for model integration [21] |

| Metanetx | Biochemical reaction database with cross-references | Reaction and metabolite standardization across models [22] | |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Curated protein sequence database | Gene-protein-reaction association validation [21] | |

| Experimental Assays | Chemically Defined Media | Precisely controlled nutrient composition | Auxotrophy validation and growth phenotyping [21] |

| Transposon Mutagenesis Libraries | Genome-wide mutant collections | Experimental gene essentiality validation [17] | |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Analytical instrumentation for metabolite detection | Metabolomic validation of predicted metabolic capabilities [23] |

Consensus metabolic modeling represents a significant methodological advancement in systems biology, effectively addressing the limitations of individual reconstruction approaches by integrating their complementary strengths. Through systematic comparison and integration of multiple GEMs, consensus approaches enhance metabolic network certainty, improve functional prediction accuracy, and provide more reliable platforms for investigating metabolic processes across diverse biological systems [17] [2].

The structural and functional advantages of consensus models—including their expanded reaction coverage, reduced dead-end metabolites, and improved genomic evidence support—translate directly into enhanced performance for critical prediction tasks such as auxotrophy assessment and gene essentiality identification [17] [2]. Furthermore, their ability to outperform even manually curated gold-standard models in specific applications demonstrates the value of synthesizing knowledge from multiple automated reconstructions [17].