Culturing the Uncultured: Innovative Strategies to Overcome Marine Microorganism Cultivation Barriers

Marine microorganisms represent a vast reservoir of untapped biological diversity with immense potential for drug discovery and biotechnology.

Culturing the Uncultured: Innovative Strategies to Overcome Marine Microorganism Cultivation Barriers

Abstract

Marine microorganisms represent a vast reservoir of untapped biological diversity with immense potential for drug discovery and biotechnology. However, the majority of these organisms have historically been inaccessible due to formidable cultivation challenges, often referred to as the 'great plate count anomaly.' This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest scientific advances to overcome these limitations. We explore the foundational reasons for microbial uncultivability, detail innovative methodological approaches from in situ cultivation to growth-curve-guided strategies, present troubleshooting and optimization frameworks for media and conditions, and validate findings through comparative and functional profiling. The integration of these advanced cultivation techniques with omics technologies is paving the way for discovering novel bioactive compounds and unlocking the full potential of marine microbial resources for biomedical applications.

Understanding the Uncultured Majority: Why Marine Microbes Resist Laboratory Cultivation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the "Great Plate Count Anomaly" in marine microbiology? The "Great Plate Count Anomaly" describes the significant discrepancy, often several orders of magnitude, between the number of microbial cells observed in a marine sample via microscopy and the much smaller number that form colonies on standard agar media [1] [2]. In oceanic waters, traditional plating techniques typically culture only 0.01% to 0.1% of the total bacterial cells present, leaving the vast majority of microbial diversity uncharacterized and uncultured [1].

FAQ 2: Why are the majority of marine microorganisms considered "unculturable"? Marine microbes resist cultivation for several interconnected reasons:

- Non-standard Nutrient Conditions: Many indigenous marine bacteria are oligotrophic, meaning they are adapted to environments with very low nutrient concentrations. The high nutrient levels in standard laboratory media can inhibit their growth or even be toxic [1] [2].

- Unknown Growth Requirements: Specific, unidentified growth factors, vitamins, or signaling molecules present in their natural habitat may be absent in synthetic media [3] [2].

- Microbial Interdependence: In nature, bacteria often grow as consortia, relying on metabolic by-products from other species for essential nutrients. Standard isolation techniques disrupt these critical syntrophic interactions [2] [4].

- Dormancy States: A portion of the microbial community may exist in a dormant or slow-growing state, unable to rapidly proliferate under laboratory conditions [5].

FAQ 3: What are the key differences between "culturable" and "non-culturable" states? The distinction is not necessarily permanent but reflects whether the correct laboratory conditions have been discovered.

Table: Contrasting Culturable and Non-Culturable States

| Feature | Culturable State | Non-Culturable State |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Growth | Grows on standard media | Requires specialized, often unknown, conditions |

| Nutrient Preference | Often copiotrophic (high nutrients) | Often oligotrophic (low nutrients) |

| Growth Rate | Typically faster | Can be extremely slow |

| Dependency | Often grows axenically | May require microbial neighbors (syntrophy) |

| Physiological State | Active | Can be active, dormant, or viable but non-culturable (VBNC) |

FAQ 4: Has the estimated proportion of culturable marine microbes changed? Yes, with improved cultivation strategies, estimates have increased for some environments. While the 0.01-0.1% figure is classic, modern approaches like high-throughput extinction culturing have successfully cultured up to 14% of cells from coastal seawater samples, demonstrating that a significantly larger fraction is cultivable if the correct methods are used [1]. Recent studies analyzing diverse communities across biomes have found that a significant proportion of microorganisms have known culturable relatives, suggesting the gap may be narrower than traditionally thought, though still substantial [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Failure to Isolate Dominant Microbial Taxa Revealed by Genetic Surveys

Symptoms: Genetic analysis (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing) of your seawater sample shows a high abundance of Alphaproteobacteria (e.g., the SAR11 clade). However, your plating results on Marine Agar 2216 or R2A yield primarily Gammaproteobacteria [2].

Diagnosis: The standard, nutrient-rich media and high-oxygen plating conditions favor fast-growing, copiotrophic bacteria that are often minor community members in the open ocean, while suppressing the growth of the more abundant oligotrophic specialists [2].

Solution: Simulate the Natural Environment.

- Reduce Nutrient Concentration: Use oligotrophic media, such as diluted Marine R2A (e.g., 1/10 or 1/100 strength) or filtered, autoclaved, and buffered natural seawater [1] [2].

- Extend Incubation Time: Incubate plates for several weeks to months to accommodate slow-growing organisms [2].

- Modify Gelling Agent: Substitute agar with gellan gum. Agar can contain growth-inhibiting impurities, and gellan gum has been shown to increase viable counts and recovery of different bacterial taxa [4].

Table: Reagent Solutions for Oligotrophic Cultivation

| Research Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Filtered & Autoclaved Natural Seawater | Serves as a low-nutrient, chemically accurate base medium. |

| Gellan Gum | A purified gelling agent that can replace agar to reduce oxidative stress on sensitive marine isolates. |

| Catalase or Sodium Pyruvate | Scavenges hydrogen peroxide that can form in autoclaved media, reducing oxidative stress on cells [4]. |

Problem 2: Inability to Cultivate Microbes Dependent on Microbial Interactions

Symptoms: Microscopic counts confirm high cell density in a liquid enrichment, but you cannot obtain pure isolates on solid media. This suggests growth may depend on substances produced by other cells.

Diagnosis: The target microorganism has obligate or facultative syntrophic relationships with other microbes. Physical separation on a plate eliminates these essential cross-feeding interactions [2].

Solution: Facilitate Microbial Communication.

- Diffusion Chambers (e.g., iChip): Immerse a semi-permeable membrane containing diluted cells directly in the native environment, allowing chemical exchange with the surrounding seawater [4].

- Conditioned Media: Filter the spent medium from a mixed enrichment culture and use it to supplement fresh, low-nutrient media. This provides unknown growth factors produced by the community.

- Co-culture Experiments: Systematically culture the target organism with one or more helper strains that may provide essential nutrients or signaling molecules.

Problem 3: Low-Throughput and Insensitive Detection of Growth

Symptoms: When using low-nutrient media in small volumes (e.g., 96-well plates), culture growth is so slow and dilute that it is invisible to the naked eye, leading to false negatives.

Diagnosis: Standard visual inspection lacks the sensitivity to detect low-density microbial growth, especially in extinction culturing where initial inocula can be very small [1].

Solution: Implement High-Throughput, Sensitive Detection.

- Cell Arrays for Fluorescence Microscopy: This method involves filtering aliquots from multiple microtiter wells onto a single membrane, staining with DAPI, and examining under a fluorescence microscope. This allows for the efficient screening of thousands of cultures and detection of cell densities as low as 1.3 × 10³ cells/mL [1].

- Flow Cytometry: Use flow cytometry to automatically count and characterize cells in liquid cultures, providing a rapid and sensitive measure of growth, even in very dilute cultures [1].

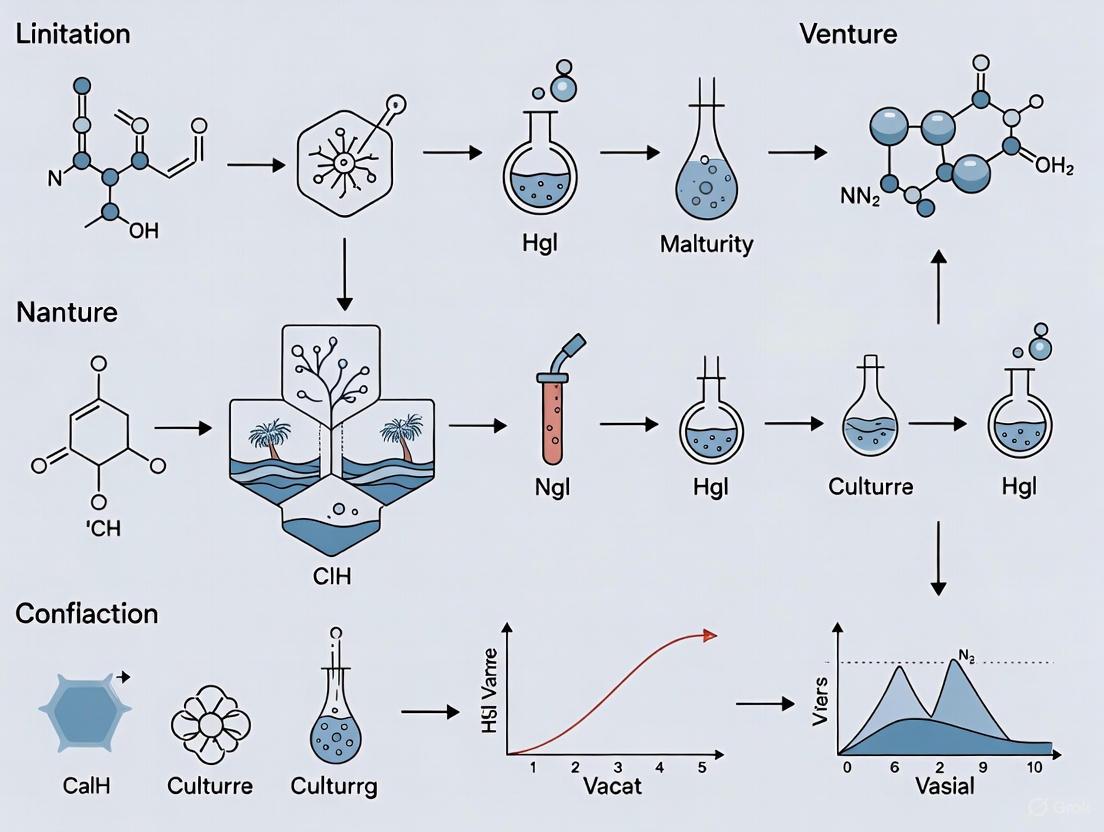

The following workflow diagram illustrates the high-throughput culturing (HTC) method that integrates these solutions:

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Extinction Culturing

This protocol is adapted from Connon and Giovannoni (2002) and is designed to isolate previously uncultured oligotrophic marine bacteria [1].

Objective: To culture a diverse array of marine bacterioplankton by simulating in situ substrate concentrations and using high-throughput screening.

Materials:

- Media: Seawater collected from the target environment, filtered (0.2 µm), autoclaved, and sparged with CO₂/air to restore bicarbonate buffer.

- Inoculum: Fresh marine water sample, processed within hours of collection.

- Equipment: 48-well non-tissue-culture-treated polystyrene plates; custom 48-array filter manifold; 0.2 µm white polycarbonate membrane; fluorescence microscope.

Method:

- Media Preparation: Filter and autoclave seawater. Sparge with sterile COâ‚‚ for 6 hours, then with sterile air for 12 hours. Check for sterility by DAPI staining and counting.

- Sample Inoculation:

- Perform direct cell counts (via DAPI stain) on the inoculum to determine cell density.

- Dilute the inoculum in the prepared seawater medium to a final concentration of approximately 1 to 5 cells per well.

- Dispense 1 mL aliquots into the 48-well plates. Include control plates with uninoculated medium.

- Incubation: Incubate plates in the dark at in situ temperature (e.g., 16°C) for 3 weeks.

- Detection of Growth via Cell Array:

- Filter 200 µL from each well into the corresponding chamber of the 48-array filter manifold.

- DAPI-stain the cells directly on the membrane.

- Transfer the membrane to a microscope slide and cover with a cover glass.

- Systematically scan each sector of the array using a fluorescence microscope. Score a well as positive if cells are present.

- (Optional) Estimate cell titer by counting cells in five random fields within positive sectors.

- Culture Recovery: Return to the original 48-well plate and recover the culture from positive wells for further purification and identification (e.g., by 16S rRNA gene sequencing).

Marine microorganisms are a vast reservoir of untapped biological potential, promising new bioactive compounds for drug development and sustainable food resources [6]. However, culturing these microbes in the laboratory presents significant challenges. In nature, marine microbes frequently exist in a state of slow growth or near-zero growth due to severe nutrient limitation and adverse conditions, a stark contrast to the optimal environments typically used in laboratory settings [7]. This discrepancy, compounded by issues of nutrient specificity and unidentified growth requirements, means that a vast majority of marine microbial diversity remains uncultured and unstudied. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers overcome these specific barriers, framed within the broader thesis of advancing marine microbiology research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Fundamental Challenges in Marine Microbial Culturing

Why is it so difficult to culture marine microorganisms in the lab? The primary challenge is the mismatch between laboratory conditions and natural marine environments. Most culturing methods use nutrient-rich media, but in the ocean, microbes are adapted to survive under extreme nutrient limitation and complex biotic interactions that are difficult to replicate [7] [8].

What is "near-zero growth" and why is it important? Near-zero growth is a state of maintenance metabolism where microbial cells are alive and metabolically active, but not dividing. In nature, this is the dominant state for many microbes due to limited nutrients. Understanding and replicating these conditions is key to cultivating a wider diversity of organisms [7].

How do microbial interactions affect culturing success? Marine microbes exist in complex communities where they "talk to each other with a chemical language" [8]. Some bacteria provide essential nutrients like B-vitamins to their neighbors, while others produce algicidal compounds [9]. Isolating a microbe severs these critical interactions, which can halt growth.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Consistent Failure in Isolating Target Microbes from Marine Samples.

- Potential Cause 1: Standard media are too nutrient-rich.

- Solution: Employ nutrient dilution methods. Use oligotrophic media, such as diluted R2A seawater agar or a 1:10 dilution of a standard marine broth (e.g., Marine Broth 2216) with filter-sterilized seawater. This mimics the low-nutrient conditions many marine microbes are adapted to [7].

- Potential Cause 2: Missing essential chemical signals or cofactors from their natural community.

- Solution: Implement co-culture or conditioned media techniques.

- Co-culture: Introduce a "helper" strain, such as Mameliella alba, which has been shown to provide essential B-vitamins to other microbes [9].

- Conditioned Media: Filter the supernatant from a growing microbial community from the same environment and add it (e.g., 10-50% v/v) to your sterile growth medium to introduce missing signaling molecules [9].

- Solution: Implement co-culture or conditioned media techniques.

- Potential Cause 3: Unidentified growth requirements.

- Solution: Utilize high-throughput screening with various nutrient amendments. Prepare a base minimal seawater medium and supplement different wells of a microtiter plate with various single carbon sources (e.g., pyruvate, acetate, chitin), nitrogen sources, or other potential nutrients to identify specific requirements.

Problem: Isolates Grow Exceptionally Slowly or Enter Stationary Phase Prematurely.

- Potential Cause: The laboratory environment fails to replicate the slow-growth state that is the organism's natural condition.

- Solution: Use continuous culture systems like chemostats. Instead of batch culture, use a chemostat to maintain a constant, very slow growth rate under controlled nutrient limitation. This allows the study of microbial physiology and secondary metabolite production under conditions that more closely resemble their natural state [7].

Problem: Inability to Replicate Natural Product (e.g., Antimicrobial) Production in Lab Cultures.

- Potential Cause: Secondary metabolite production is often activated under stress or growth-limiting conditions, not during optimal, rapid growth.

- Solution: Induce stress responses. Once a pure culture is obtained, experiment with stress factors such as:

Summarized Data and Protocols

Table: Microbial Growth Phases and Metabolic States

| Growth Phase / State | Key Characteristics | Relevance to Marine Culturing |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential Phase | Rapid cell division, high metabolic activity. | Typical target of lab cultures; rare in natural marine environments [7]. |

| Stationary Phase | Growth cessation due to nutrient depletion/waste accumulation; activation of stress responses & secondary metabolite production [7]. | A critical state to study for discovering novel bioactive compounds [7]. |

| Near-Zero Growth | Maintenance metabolism, minimal to no cell division; cells remain viable and metabolically flexible [7]. | The dominant state in oceans; key to unlocking "microbial dark matter" [7]. |

Table: Common Nutrient Amendments and Functions

| Nutrient / Amendment | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Pyruvate | Alternative carbon and energy source; can enhance recovery of stressed cells. | Added at 0.05-0.1% (w/v) to isolation media for samples from low-energy environments. |

| B-Vitamin Mix | Essential cofactors for many metabolic enzymes; often provided by symbionts in nature [9]. | Add a filter-sterilized vitamin mix (e.g., Balch's vitamins) to minimal media at 1 mL/L. |

| Signal Molecules (e.g., AHLs) | Quorum sensing molecules that regulate group behaviors like bioluminescence and biofilm formation. | Use synthetic AHLs (e.g., N-(3-Oxooctanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone) at nanomolar concentrations to induce specific pathways. |

Experimental Protocol: Simulating Nutrient-Limited Conditions for Isolation

Objective: To isolate marine microorganisms adapted to oligotrophic conditions by simulating their natural low-nutrient environment.

Materials:

- Filter-sterilized (0.22 µm) seawater, collected from the same site as the sample if possible.

- Gelling agent (e.g., Gellan Gum for a clear, low-nutrient gel).

- ï‚£ 50 mm Petri dishes.

- Marine sediment or water sample.

Methodology:

- Media Preparation: Prepare a 10x stock solution of a minimal salts medium (e.g., containing NHâ‚„Cl, Kâ‚‚HPOâ‚„). Dilute this stock 1:10 with filter-sterilized seawater to create a 1x working solution.

- Gelling: Add a low concentration of Gellan Gum (e.g., 0.5-0.8% w/v) to the diluted medium. Heat to dissolve completely.

- Pouring Plates: Autoclave the medium and allow it to cool to approximately 45°C before pouring into sterile Petri dishes.

- Inoculation: Spread-plate a low concentration of the marine sample (e.g., 50-100 µL of a diluted sample) onto the solidified medium.

- Incubation: Seal plates in plastic bags to prevent desiccation and incubate at the in situ temperature (or a relevant range) for 4 to 12 weeks, monitoring periodically for the appearance of very slow-growing microcolonies [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Overcoming Marine Culturing Barriers

| Item | Function | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Oligotrophic Media | Provides a low-nutrient base that prevents the overgrowth of fast-growing species and supports slow-growing specialists. | Dilute Marine Broth, R2A Seawater Agar, Synthetic Seawater Medium with trace carbon. |

| Chemical Supplementations | Provides specific nutrients or signals that are missing in artificial media but required for growth. | B-Vitamin Mix, Sodium Pyruvate, Quorum Sensing Molecules (AHLs), Siderophores. |

| Continuous Culture Systems (Chemostats) | Maintains microbial populations in a steady state of slow growth under precise nutrient limitation, mimicking natural conditions [7]. | Bench-top bioreactor systems with controlled nutrient feed and effluent removal. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits (Marine) | For molecular validation of culture identity and analysis of community DNA/RNA from initial samples to guide culturing efforts. | Metagenomic DNA extraction kits optimized for low-biomass, high-inhibitor marine samples. |

| Gellan Gum | A superior gelling agent for forming a clear, solid surface with less potential for inhibition than agar, ideal for visualizing microcolonies. | Gelrite, Phytagel. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Microbial Interaction Network Influencing Growth

Diagram: Workflow for Isolating Slow-Growth Marine Microbes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common reasons for culture failure when working with microorganisms from extreme environments? Culture failure is frequently due to an environmental mismatch between the natural habitat and the laboratory culture conditions. Common specific reasons include: inaccurate replication of physicochemical conditions (temperature, pH, hydrostatic pressure), the presence of toxic oxygen levels for anaerobic taxa, inadequate supply of specific electron donors/acceptors, and missing essential trace elements or growth factors found in the native environment [10].

Q2: Which physicochemical parameters are most critical to replicate for deep-sea hydrothermal vent microorganisms? The most critical parameters to control are temperature, pH, and specific electron donors and acceptors [10]. The required values vary significantly between taxa, as shown in Table 1. For example, many chemosynthetic organisms rely on hydrogen or sulfur compounds as energy sources [11].

Q3: How can I prevent oxidative stress in anaerobic isolates from anoxic environments like hydrothermal vents or sediments? Maintain a strict anoxic environment throughout the cultivation process. This involves using an anaerobic chamber or sealed tubes with an anoxic gas headspace (e.g., Nâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ or Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ mixes). The culture medium should be pre-reduced with supplements like sodium sulfide (Naâ‚‚S) or cysteine-HCl [10].

Q4: What is the significance of large genome sizes discovered in some marine bacteria, and how might it affect their culturing? The discovery of bacterial genomes up to 18.4 Mb in size, redefining the upper limit for marine bacteria, suggests a high degree of metabolic versatility and regulatory complexity [12]. These organisms may have evolved under conditions of high environmental variability. To culture them, it may be necessary to provide a complex mixture of nutrients or simulate fluctuating conditions that mimic their native ecosystem [12].

Q5: Can you provide an example of a successful cultivation methodology for a nitrous oxide (Nâ‚‚O)-reducing bacterium from a deep-sea vent? A novel thermophilic bacterium from the Okinawa Trough was successfully cultured. It can use the greenhouse gas Nâ‚‚O as a terminal electron acceptor, reducing it to harmless Nâ‚‚ gas. It can also utilize COâ‚‚ as a carbon source. Culture experiments were conducted under elevated temperature and specific gas mixtures (Nâ‚‚O, COâ‚‚) to demonstrate this high reduction ability [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: No Growth in Inoculated Cultures

| Possible Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Temperature | Verify the optimal temperature for your target organism (see Table 1). | Research the isolation source's known temperature range before setting up cultures [10]. |

| Inadequate Energy Source | Provide a mix of potential electron donors (Hâ‚‚, Sâ°, Sâ‚‚O₃²â») and acceptors (Oâ‚‚, NO₃â», Sâ°, SO₄²â»). | Design media based on meta-omics data from the source environment [10]. |

| Oxidative Stress | Ensure anoxic conditions for anaerobes by using resazurin as a redox indicator. | Pre-reduce media and use anaerobic work chambers for strict anaerobes [10]. |

| Missing Growth Factors | Supplement media with yeast extract, vitamins, or trace element mixtures. | Co-culture with other microbes from the same environment or use habitat-simulated medium [10]. |

Issue 2: Growth Inhibition After Initial Success

| Possible Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Toxin Accumulation | Sub-culture into fresh medium or use a continuous culture system. | Use a larger medium-to-inoculum volume ratio to dilute waste products. |

| Nutrient Depletion | Replenish energy sources and carbon donors during extended cultivation. | Monitor metabolic substrates and products (e.g., Hâ‚‚S, CHâ‚„) in real-time if possible [10]. |

| pH Shift | Monitor pH during growth and use buffered media with HEPES or PIPES. | Adjust the buffer capacity and type to match the natural habitat's stability [13]. |

| Precipitation | Check for precipitation of metal sulfides or other ions; adjust medium composition. | Ensure thorough mixing and proper dissolution of all medium components [13]. |

Data Tables

| Genus (Phylum) | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Metabolism & Electron Usage | Isolation Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desulfurobacterium (Aquificae) | 65 - 75 | Anaerobe, autotroph, Hâ‚‚-oxidizer, Sâ°-reducer | Chimney, sulfide, animal |

| Persephonella (Aquificae) | 73 | Aerobe/anaerobe, autotroph, S-oxidizer | Chimney |

| Caminibacter (Campylobacterota) | 55 - 60 | Aerobe/anaerobe, autotroph, Hâ‚‚-oxidizer, Sâ°-reducer | Chimney |

| Nautilia (Campylobacterota) | 40 - 60 | Anaerobe, autotroph/heterotroph, Hâ‚‚-oxidizer, Sâ°-reducer | Chimney, animal |

| Sulfurovum (Campylobacterota) | 28 - 35 | Aerobe/anaerobe, autotroph, S-oxidizer, Hâ‚‚-oxidizer | Chimney, sediment, rock, animal |

| Deferribacter (Deferribacteres) | 60 - 65 | Anaerobe, heterotroph, Hâ‚‚-oxidizer, Fe-reducer | Chimney, fluid |

| Marinithermus (Deinococcus-Thermus) | 67.5 | Aerobe, heterotroph | Chimney |

| Pathway | Description | Typical Microbial Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) Cycle | The most common COâ‚‚ fixation pathway; uses RuBisCO enzyme. | Zetaproteobacteria, Thiomicrospira, Beggiatoa, animal endosymbionts. |

| Reductive Tricarboxylic Acid (rTCA) Cycle | Preferred by many anaerobes and aerobic Campylobacterota. | Desulfobacterales, Aquificales, Thermoproteales, Campylobacterota. |

| 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate (3-HP/4-HB) Cycle | Used by many mixotrophs. | Desulfobacterium autotrophicum, acetogens, methanogenic archaea. |

| Reductive Acetyl-CoA Pathway | - | Acetogenic bacteria, methanogenic archaea. |

| Dicarboxylate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Cycle | - | Deferribacter autotrophicus (can also use the roTCA cycle). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Designing a Selective Cultivation Medium for Deep-Sea Chemolithoautotrophs

Principle: This protocol outlines the steps to create a medium that supports the growth of chemosynthetic microorganisms by replicating the key chemical energy sources of their habitat [10].

Materials:

- Artificial seawater base

- Vitamin and trace element solutions

- Electron donors (e.g., Na₂S·9H₂O, Na₂S₂O₃, H₂ gas)

- Electron acceptors (e.g., Oâ‚‚, NO₃â», Sâ°, SO₄²â»)

- pH buffer (e.g., HEPES, PIPES)

- Resazurin (redox indicator)

- Anaerobic chamber or gas exchange system

Procedure:

- Base Medium Preparation: Prepare an artificial seawater solution, omitting oxygen-sensitive components.

- Add Buffers and Nutrients: Add a pH buffer suitable for the target pH (e.g., neutral for many Campylobacterota, slightly acidic for some thermophiles). Add vitamin and trace element mixes.

- Add Electron Donors/Acceptors: Based on the target physiology (see Table 1 & 2):

- For sulfur-oxidizers: Add Na₂S₂O₃ and a limited amount of O₂.

- For hydrogen-oxidizers: Equilibrate the medium with Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ gas mix.

- For sulfate-reducers: Add Na₂S as a reducing agent and SO₄²⻠as an electron acceptor.

- Set Redox Potential: Add resazurin. For anaerobes, pre-reduce the medium by boiling and sparging with Nâ‚‚, then add a reducing agent like Naâ‚‚S until the resazurin becomes colorless.

- Dispense and Inoculate: Dispense the medium into tubes or bottles. For anaerobes, do this within an anaerobic chamber or with continuous sparging of anoxic gas. Inoculate with sample material.

- Incubate: Incubate at the appropriate temperature and pressure, if applicable. Monitor for growth visually (turbidity), microscopically, or via chemical consumption/production (e.g., Hâ‚‚S production).

Diagrams and Workflows

Cultivation Workflow for Extreme Marine Microbes

Key Microbial Carbon Fixation Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cultivation |

|---|---|

| Artificial Seawater Base | Provides the fundamental ionic composition (Naâº, Mg²âº, Clâ», SO₄²â») of the marine environment. |

| HEPES/PIPES Buffers | Maintains a stable pH in the medium, critical for replicating specific microniches (e.g., neutral vs. acidic vents). |

| Sodium Sulfide (Na₂S·9H₂O) | Acts as a reducing agent to maintain anoxic conditions and as an electron donor for sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | A common, soluble electron donor for cultivating sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms. |

| Hydrogen Gas (Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ Mix) | Serves as an electron donor for hydrogen-oxidizing chemolithoautotrophs and a carbon source with COâ‚‚. |

| Nitrate (NO₃â») / Nitrous Oxide (Nâ‚‚O) | Acts as an alternative electron acceptor for denitrification and, for Nâ‚‚O, studies on greenhouse gas reduction [11]. |

| Vitamin & Trace Element Mixes | Supplies essential cofactors and micronutrients required for microbial growth that may be absent in a defined basal medium. |

| Resazurin | A redox indicator that turns pink in the presence of oxygen, visually confirming the anoxic status of the medium. |

| Gellan Gum | A substitute for agar to solidify media, as it is more stable at high temperatures and does not inhibit growth of some fastidious organisms. |

| VDR agonist 3 | VDR agonist 3, MF:C24H36O7, MW:436.5 g/mol |

| tBID | tBID, MF:C11H3Br4N3O2, MW:528.78 g/mol |

FAQs: Overcoming Challenges in Marine Microorganism Research

FAQ 1: Why should I use co-culture instead of genetic engineering to activate silent biosynthetic pathways? Genetic engineering often faces challenges with plasmid instability and a substantial metabolic burden on engineered strains, which can lead to the loss of desired traits during growth [14]. Co-culture mimics natural ecosystems, where microbial interactions provide a balanced distribution of energy resources for cell growth and the coordinated expression of metabolic pathways necessary for metabolite synthesis [14]. This approach leverages ecological interactions to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters without the need for complex genetic manipulation [15].

FAQ 2: My co-culture does not produce the expected new metabolites. What could be wrong? The outcome of a co-culture system is highly specific to the paired microorganisms and the environmental conditions [16]. The results may not always be novel compounds and can instead manifest as one of three outcomes:

- A significant increase in the yield of known bioactive compounds [16].

- The production of known compounds that were not detected in axenic monocultures [16].

- The production of previously undescribed compounds [16]. Success depends on factors like nutrient availability, the presence of signaling molecules, and the dynamics of intercellular communication [14].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the stability and reproducibility of my microbial consortia? Community stability is a recognized challenge in co-culture technology. To improve stability:

- Optimize environmental factors such as medium composition, pH, and nutrient availability, as these heavily shape interactions and metabolic activities [14].

- Aim for a balanced growth of both partners, as some systems require this for reproducible metabolite production [16].

- Explore the use of synthetic communities with well-defined genetic backgrounds to reduce unpredictability [17].

FAQ 4: What is the "phycosphere" and why is it important for microbial interactions? The phycosphere is a microscale mucosal region around a phytoplankton cell, analogous to the rhizosphere of terrestrial plants [17]. It is a critical environment where metabolic interactions between the phytoplankton and associated bacteria and archaea navigate the biochemistry of the sea [17]. Studying these micro-environments is essential for understanding how metabolic interactions drive large-scale biochemical processes [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or Undetectable Yield of Target Metabolites

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters | Perform genomic analysis (e.g., antiSMASH) to identify cryptic gene clusters not expressed in lab conditions [16]. | Employ co-culture with a challenging partner. Example: Co-culture of *Streptomyces cinnabarinus with Alteromonas sp. induced a 10.4-fold increase in the antifouling diterpene lobocompactol [16]. |

| Sub-optimal Culture Conditions | Analyze the impact of different media (solid vs. liquid), salinity, and carbon sources on metabolomic profiles. | Implement the OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) approach. Systematically vary culture parameters like medium composition and agitation to activate different pathways [15]. |

| Lack of Essential Ecological Signals | Check if the co-culture requires physical contact or close proximity for metabolite induction. | Optimize the cultivation method. Example: Static incubation was critical for the balanced growth of *Streptomyces sp. and Bacillus mycoides, leading to significant production of bacillamides and tryptamine derivatives [16]. |

Problem: Unstable Co-culture with One Strain Dominating

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive Exclusion | Monitor individual population dynamics in the co-culture using colony-forming unit (CFU) counts or qPCR. | Engineer syntrophy by designing the system so that the waste product of one strain is the nutrient source for the other, creating mutual dependence [14]. |

| Inhibitory Metabolite Production | Identify the inhibitory compound through metabolomic analysis of the culture supernatant. | Introduce a resistant partner. Example: Using a lobocompactol-resistant strain of *Alteromonas sp. allowed for stable co-culture and high production of the compound [16]. |

| Nutrient Imbalance | Analyze the medium composition to ensure it does not preferentially support one strain. | Use a minimal or defined medium that forces interdependence, or use fed-batch techniques to control nutrient availability [14]. |

Quantitative Data on Co-culture Outcomes

The table below summarizes documented results from marine bacterial co-cultures, demonstrating the potential of this approach to enhance metabolite production.

Table 1: Enhanced Metabolite Production in Marine Bacterial Co-cultures

| Co-culture System | Metabolite(s) Produced | Outcome vs. Monoculture | Reference Activity/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces cinnabarinus PK209 + Alteromonas sp. KNS-16 | Lobocompactol (antifouling diterpene) | 10.4-fold increase in production | [16] |

| Streptomyces sp. CGMCC4.7185 + Bacillus mycoides | Bacillamides A-C, Tryptamine derivatives | Significant increase; compounds barely detected in axenic culture | [16] |

| Streptomyces sp. PTY087I2 + MRSA | Granatomycin D, Granaticin, Dihydrogranaticin B | Significantly increased antibacterial activity and compound detection | MIC against MRSA: 6.25 μg/ml [16] |

| Streptomyces sp. ANAM-5 + Streptomyces sp. AIAH-10 | Crude extract with anticancer activity | 75.75% inhibition of EAC cells at 100 mg/kg dose | Increased mouse lifespan by 71.79% [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Co-culture for Antibacterial Compound Induction

This protocol is adapted from a study where co-culture of Streptomyces sp. PTY087I2 with pathogen bacteria induced enhanced production of naphthoquinone derivatives with antibacterial activity [16].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Strains: Target marine bacterium (e.g., Streptomyces sp.), inducing pathogen (e.g., Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)).

- Growth Medium: Liquid medium per liter: Peptone (1 g), Yeast Extract (2 g), Starch (5 g), Instant Ocean (33 g) [16].

- Equipment: Shaker incubator, Centrifuge, Laminar flow hood, Erlenmeyer flasks.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Pre-culture. Inoculate the marine bacterium and the inducing pathogen separately into the growth medium. Incubate at 30°C with shaking for 24-48 hours to establish active cultures [16].

- Step 2: Inoculation. In a fresh flask containing the growth medium, inoculate with the pre-cultured marine bacterium. The inducing pathogen can be added simultaneously or after a delay, depending on the experimental design.

- Step 3: Co-culture Fermentation. Incubate the co-culture at 30°C for 10 days with agitation (e.g., 220 rpm) [16].

- Step 4: Harvest and Extraction. After incubation, separate the biomass from the culture broth by centrifugation. The cell-free supernatant can be extracted with an organic solvent like ethyl acetate. The biomass can be extracted with a solvent like methanol.

- Step 5: Analysis. Analyze the crude extracts for antibacterial activity using assays like Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and for chemical composition using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [16].

Protocol 2: Static Co-culture for Metabolite Optimization

This protocol is effective for co-culture systems that require balanced, static growth for optimal metabolite production, as demonstrated with Streptomyces sp. and Bacillus mycoides [16].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Strains: The two marine bacteria to be co-cultured.

- Optimized Medium: Per liter: Glycerol (5 g), Yeast Extract (5 g), 75% seawater, pH 8.0 [16].

- Equipment: Static incubator.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Pre-culture the Producer. Inoculate the primary metabolite producer (e.g., Streptomyces sp.) into the optimized medium and incubate with shaking for 7 days [16].

- Step 2: Introduce the Partner. After 7 days, add a 1% (v/v) inoculum of the challenging partner (e.g., B. mycoides) to the established culture [16].

- Step 3: Static Co-culture. Transfer the co-culture to static incubation conditions (without shaking) and incubate for an additional 14 days [16].

- Step 4: Monitoring and Harvest. Monitor the system for balanced growth. Harvest and extract as described in Protocol 1.

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Interactions in Co-culture

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms and signaling interactions that are activated in a successful microbial co-culture system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Marine Microbe Co-culture Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Item Example | Function in Co-culture Research |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media Components | Instant Ocean / Artificial Sea Salts | Replicates the natural marine ionic environment, crucial for osmoregulation and function of marine isolates [16]. |

| Glycerol & Yeast Extract | Common carbon and nitrogen sources in optimized media for marine actinomycetes; their concentration can be tuned to force interdependence [16]. | |

| Elicitor Strains | Mycolic-acid-containing Bacteria | Used to challenge actinomycetes, often leading to activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters and production of new antibiotics [16]. |

| Resistant Pathogen Strains (e.g., MRSA) | Co-culture with resistant targets can induce the producer strain to synthesize defensive antimicrobial compounds [16]. | |

| Analytical Tools | LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Essential for detecting, identifying, and quantifying known and novel metabolites in complex co-culture extracts [16]. |

| AntiSMASH (Software) | A genomic tool used to identify Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in a strain's genome, guiding the choice of co-culture candidates [16]. | |

| 8-CPT-6-Phe-cAMP | 8-CPT-6-Phe-cAMP, MF:C22H19ClN5O6PS, MW:547.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sp-8-pCPT-PET-cGMPS | Sp-8-pCPT-PET-cGMPS, MF:C24H19ClN5O6PS2, MW:604.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Cultivation Techniques: From In Situ Chambers to Microfluidic Devices

The Core Challenge: Why Marine Microorganisms Resist Cultivation

A fundamental obstacle in marine microbiology is the "great plate count anomaly"—the observation that typically only 1% of marine bacteria seen under a microscope can be cultured using standard laboratory procedures [18]. The majority of marine microorganisms have evolved to thrive in specific, often extreme, environments characterized by unique combinations of temperature, light, pressure, nutrient availability, and biological interactions [19] [20] [21]. When removed from these intricate environmental networks and placed on conventional, nutrient-rich agar plates, many microbes enter a dormant state or simply fail to grow, limiting our access to their bioactive potential [21].

Strategic Framework: Matching Cultivation Strategies to Microbial Physiology

To systematically address uncultivability, researchers categorize target microorganisms based on their abundance and physiological state, with each group requiring a distinct isolation strategy [21].

Technical Solution 1: Advanced Gelling Agents as Solid Substrates

The choice of gelling agent is a critical, yet often overlooked, factor that significantly impacts the culturability of marine microbes. Moving beyond traditional agar can dramatically improve recovery rates.

Comparison of Common Gelling Agents

| Gelling Agent | Source | Melting Temp. | Key Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agar [22] [23] | Red Seaweed (Gelidium, Gracillaria) | ~85°C | Standard; good clarity; metabolically inert for many microbes | General purpose; mesophilic cultures |

| Gellan Gum [18] [22] | Bacterium (Sphingomonas elodea) | ~110°C | High clarity; forms gel with cations (Mg²âº, Ca²âº); stable at low concentrations | Improving overall diversity; previously uncultured groups |

| Gelatin [22] | Animal Collagen | ~37°C | Digested by many bacteria; low melting point | Historical use; not recommended for most microbial work |

| Carrageenan [22] | Red Seaweed | 50-80°C | Stable at high pH | Cultivating alkaliphilic microorganisms |

| Xanthan Gum [22] | Bacterium (Xanthomonas campestris) | ~270°C | Stable over wide pH/temperature range; high viscosity | Growing various bacteria and fungi |

Key Experimental Findings

- Superiority of Gellan Gum: Replacing agar with gellan gum in media formulations increased viable counts by 3 to 40-fold, achieving culturability of up to 6.6% of total bacterial counts compared to a maximum of 2.3% on agar-based substrates [18].

- Enhanced Diversity: The culturable bacterial communities grown on gellan gum were significantly different and more representative of the original seawater community than those grown on agar, enabling the growth of bacterial orders that did not form colonies on agar [18].

Technical Solution 2: Mimicking the Natural Environment

Abiotic Factor Control

Creating an incubation environment that closely mirrors the dynamic conditions of the target marine habitat is crucial for success.

- Dynamic Temperature and Light Control: A modified shaking water bath system can be programmed with fully customizable temperature and light gradients, or can scrape and mimic real-time field data from coastal buoys. This allows for the simulation of natural diurnal cycles, which are critical for maintaining authentic microbial community structure and function [19].

- Chemical Composition: Using filtered, autoclaved natural seawater as the base for media, rather than artificial seawater, helps to preserve essential trace elements and micronutrients. For oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) microbes, creating low-nutrient media such as SWG (Seawater Gellan gum) is essential to avoid overfeeding and metabolic shock [18].

Incorporating Biotic and Signaling Factors

- Quorum Sensing Molecules: Supplementing media with acylated homoserine lactones (AHLs), which are bacterial signaling molecules, has been shown to increase the relative abundance of certain bacterial groups like Sphingobacteria, though the effect on total viable counts can be variable [18].

- Co-culture and Diffusion Systems: Devices like the iChip (isolation chip) allow for the cultivation of microbes in situ or in the lab while permitting the diffusion of chemical growth factors and signaling molecules from neighboring microbes, simulating the natural web of biological interactions [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Media and Gelling Agents

Q1: My gellan gum media is forming clumps during preparation. How can I prevent this? A: Clumping occurs when the outer molecules of the gelling agent hydrate too quickly, forming a barrier that prevents the medium from penetrating. To avoid this:

- Use a magnetic stirrer to ensure rapid and thorough mixing while adding the gelling agent to the hot liquid [25].

- Consider adding a small amount of glycerol as a wetting agent to reduce clump formation [25] [23].

- Sieve the powder into the medium while stirring gently [23].

Q2: My solid culture media appears watery and has a glassy appearance. What is happening? A: This is a sign of vitrification (or hyperhydricity), which is caused by excessive hydration of the medium [25].

- Solution: Increase the concentration of your gelling agent to reduce the water retention capacity of the media [25].

Q3: How long should I wait for marine isolates to grow? A: Patience is key. Many marine oligotrophs are slow-growing. Incubation times can vary significantly:

- Standard incubation at 25°C may require at least 2 to 5 weeks for colony formation [18].

- Incubation at lower temperatures (e.g., 10°C) for samples from cold environments may require extended incubation of 5 to 10 weeks or more [18].

Experimental Protocol: Culturing with Gellan Gum

This protocol is adapted from methods shown to significantly improve the culturability of marine bacteria [18].

Objective: To prepare solid culture media using gellan gum as a gelling agent for the isolation of marine bacteria.

Materials:

- Gellan gum (e.g., Gelrite, Phytagel)

- Marine Broth (MB) or filtered natural seawater (SW)

- Divalent cation solution (e.g., MgClâ‚‚ or CaClâ‚‚, filter-sterilized)

- Standard microbiology lab equipment (autoclave, stir plate, etc.)

Procedure:

- Prepare Liquid Base: Prepare the liquid medium (e.g., Marine Broth or filtered seawater) according to your requirements. Gellan gum requires cations to gel.

- Add Gelling Agent: Add gellan gum to the cold liquid medium at a concentration of 2.0 g/L [25]. To prevent clumping, stir vigorously and continuously while sprinkling in the powder.

- Autoclave: Autoclave the medium at 121°C for 20 minutes [25]. The gellan gum will be in solution and the medium will appear clear.

- Add Cations: After autoclaving and cooling to approximately 40-50°C, aseptically add a filter-sterilized solution of MgCl₂ or CaCl₂ to a final concentration of approximately 5-10 mM. Mix gently but thoroughly. Note: Without these cations, the gellan gum will not form a firm gel.

- Pour Plates: Quickly pour the medium into sterile Petri dishes (approx. 20 mL per plate) before it solidifies.

- Inoculate and Incubate: Inoculate with your marine sample and incubate under appropriate conditions (temperature, light) for several weeks, monitoring periodically for colony formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gellan Gum [18] [25] [22] | Alternative gelling agent for improved culturability of diverse marine bacteria. | Products: Gelrite, Phytagel. Requires divalent cations (Mg²âº, Ca²âº) to solidify. |

| iChip (Isolation Chip) [24] | High-throughput in situ cultivation device that facilitates growth via diffusion of natural metabolites and signals. | Useful for isolating rare active bacteria and those dependent on helper microbes. |

| Acylated Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) [18] | Quorum-sensing signaling molecules used to induce growth in bacteria that require community signals. | Supplemented at low concentrations (e.g., 0.5 μM) in media. |

| Catalase or Sodium Pyruvate [24] | Scavenging agents added to media to reduce hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species. | Mitigates oxidative stress, improving colony formation for some sensitive strains. |

| Circulating Chiller & Heating Pads [19] | Components of a custom incubation system for creating dynamic, environmentally-relevant temperature cycles. | Essential for experiments where temperature fluctuation is a key environmental parameter. |

| CK1-IN-2 | CK1-IN-2, MF:C17H12FN3O2, MW:309.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (11Z)-eicosenoyl-CoA | (11Z)-eicosenoyl-CoA, MF:C41H72N7O17P3S, MW:1060.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: My dilution-to-extinction cultures are showing no growth. What could be the cause?

Several factors can lead to unsuccessful cultures. The table below summarizes common issues and solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No growth in wells | Medium toxicity (overly rich) or incorrect osmotic conditions [26] [21] | Use filtered seawater from the sample site as the base for the dilution medium or prepare an artificial seawater medium [26]. |

| Substrate concentration is too high, proving toxic for oligotrophs [26] [21] | Dilute standard laboratory media (e.g., 10% Tryptic Soy Broth) or use low-nutrient media specifically designed for marine oligotrophs [27]. | |

| Contamination in multiple wells | Failure of aseptic technique during sample preparation or plating [26] | Strictly practice aseptic techniques, including equipment sterilization and the use of a controlled environment like a laminar flow hood [26]. |

| Overgrowth from fast-growing strains | Inefficient separation of cells; dilution factor not optimal [28] | Perform a dilution series to achieve a theoretical concentration of 1–10 cells per well and select plates where only 30%–50% of wells show growth for isolation [26] [27]. |

FAQ 2: I am trying to isolate rare microbes using microfluidics, but my recovery rates for sorted cells are low. How can I improve this?

Low recovery rates after sorting are often related to cell stress or damage during the process.

- Use Protective Encapsulation: Techniques like double water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsions or encapsulation in gel microdroplets (agarose) can protect cells from shear stress during sorting and maintain a more favorable micro-environment. These are compatible with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [29].

- Optimize Droplet Size and Sorting Parameters: Ensure that the microdroplets are large enough to not physically damage the cells but small enough for high-throughput processing. Validate and adjust the sorting parameters (e.g., pressure, trigger threshold) on control samples to maximize viability [29].

- Employ In Situ Cultivation: For particularly fragile or fastidious cells, consider using microfluidic devices like the microbe domestication pod (MD Pod) that allow for incubation of encapsulated cells in their natural environment, bypassing the need for immediate laboratory cultivation and sorting altogether [29].

FAQ 3: My microfluidic device is prone to clogging when processing environmental marine samples. What can I do?

Clogging is a common issue with complex environmental samples.

- Implement Pre-filtration: Pre-process the sample by passing it through a filter with a larger pore size (e.g., 5-10 μm) to remove large particulate matter and debris before loading it into the microfluidic chip [30].

- Design Clog-Resistant Architectures: If designing a custom device, incorporate features that minimize trap points, such as avoiding sudden changes in channel diameter and using weir-style filters instead of pillar arrays where possible.

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: Dilution-to-Extinction Culturing for Marine Samples

This protocol is adapted for isolating marine microorganisms and is based on established methods used for plant and marine microbiota [26] [28] [27].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Filtered Seawater | Serves as the base for dilution media, mimicking the natural ionic and osmotic conditions of the sample environment [26]. |

| 10% Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | A low-nutrient growth medium suitable for oligotrophic marine bacteria. Prepared in filtered seawater [27]. |

| Sterile 1X Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Used for sample washing and preparing initial cell suspensions [28]. |

| 96-well Microplates | The platform for high-throughput dilution culturing [28] [27]. |

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation and Cell Suspension:

- For water samples, concentrate microbial biomass via filtration (e.g., onto a 0.22 μm filter) and resuspend in a small volume of sterile PBS or filtered seawater [30].

- For sediment samples, homogenize a small amount (e.g., 1 g) in sterile PBS or filtered seawater and allow large particles to settle. Use the supernatant as the cell suspension [26].

Serial Dilution:

- Perform a serial dilution of the cell suspension in your chosen growth medium (e.g., 10% TSB in filtered seawater). A threefold serial dilution series is common, starting from a 2000× dilution to over 480,000× [27].

- The goal is to statistically dilute the sample to a point where aliquots contain, on average, fewer than one cell.

Inoculation and Incubation:

- Dispense the diluted suspensions into sterile 96-well microtiter plates, typically 100-200 μL per well.

- Seal the plates to prevent evaporation and incubate them at a temperature relevant to the sample's origin (e.g., room temperature for surface water) for an extended period (e.g., 12 days to several weeks). Patience is critical, as many marine microbes are slow-growing [26] [21].

Identification of Positive Growth and Isolation:

- Screen the plates for turbidity, which indicates microbial growth.

- For downstream isolation and identification, select plates where only 18-55% of wells show growth. This increases the probability that the growth originated from a single cell [27].

- Use an aliquot from positive wells for streak plating on solid media to obtain pure cultures or proceed directly to molecular identification (e.g., 16S rRNA gene sequencing) [27].

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Isolation via Gel Microdroplet Encapsulation

This protocol outlines a high-throughput method for isolating single microbial cells using microfluidics [26] [29].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Agarose | Forms a porous gel matrix for the microdroplets, allowing diffusion of nutrients and waste while physically separating individual cells [26]. |

| Fluorinated Oil with Surfactant | Forms the oil phase for generating water-in-oil emulsions, stabilizing the droplets and preventing coalescence. |

| Lysis Buffer & PCR Master Mix | Used for downstream genetic analysis directly from the microdroplets or sorted cells. |

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated cell suspension as described in the dilution-to-extinction protocol.

Microdroplet Generation:

- Mix the cell suspension with molten, low-melting-point agarose.

- Using a microfluidic droplet generator, disperse this mixture into a flowing stream of fluorinated oil to form a water-in-oil emulsion. The conditions are controlled to generate droplets where a small fraction contain a single bacterial cell [26] [29].

- Rapidly cool the emulsion to solidify the agarose, forming gel microdroplets (GMDs).

Incubation and Screening:

- Incubate the GMDs in a nutrient medium that diffuses into the droplets.

- Cells that grow will form microcolonies within their respective droplets.

- Screen for droplets containing microcolonies, potentially using fluorescent dyes or biosensors that indicate metabolic activity or the production of a compound of interest [29].

Sorting and Recovery:

- Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to selectively sort GMDs based on the screening signal (e.g., fluorescence from a biosensor) [29].

- The sorted GMDs can be broken or dissolved to release the microcolonies for further cultivation on standard agar plates or for direct molecular analysis.

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram 1: Dilution-to-Extinction Culturing Workflow

Diagram 2: Microfluidic Gel Microdroplet Isolation Workflow

Overcoming the limitation of the "uncultured majority" is a central challenge in marine microbiology research. While metagenomics has revealed an immense diversity of marine microbes, translating this genetic blueprint into successful cultivation requires precise, data-driven strategies. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to help researchers design effective culture media based on metagenomic insights, thereby bridging the gap between sequence data and living microbial isolates.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) suggests my target bacterium should grow on my designed media, but I see no growth after 2 weeks. What should I do?

Answer: This common issue often stems from incomplete metabolic pathway interpretation or unmet growth requirements. We recommend the following systematic approach:

- Re-examine MAG Completeness and Contamination: First, verify the quality of your MAG. A genome with low completeness may be missing essential metabolic genes. Use tools like CheckM. A contamination level above 5% can lead to erroneous functional predictions.

- Analyze Auxotrophies: Your MAG likely indicates missing biosynthetic pathways for essential vitamins, amino acids, or cofactors. Consult the following table of common auxotrophies and their genomic signatures.

Table 1: Common Microbial Auxotrophies and Genomic Indicators

| Auxotrophy For | Key Missing Genes in Pathway | Potential Media Supplement |

|---|---|---|

| B Vitamins | bioF, bioB (Biotin); ribA, ribB (Riboflavin, B2) | Yeast extract (0.01-0.05%), soil extract (1-2%) |

| Amino Acids | trpC, trpD (Tryptophan); leuA, leuB (Leucine) | Casamino acids (0.02%), specific amino acid mix (50 µg/mL) |

| Heme | hemA, hemL (Heme biosynthesis) | Sterile defibrinated blood (0.5-1%), hemin (10-50 µg/mL) |

- Mimic the Natural Environment: The marine environment provides unique micronutrients. Supplement your medium with filter-sterilized seawater or sterile supernatant from a related, successful enrichment culture to provide unknown growth factors [31].

- Adjust Physical Conditions: Confirm that your incubation temperature, pH, and light conditions match the source environment. For anaerobic species, ensure a proper anaerobic chamber or sealed jar with an anaerobic gas pack.

FAQ 2: My target microbe grows very slowly and is consistently outcompeted by faster-growing contaminants. How can I selectively enrich it?

Answer: Selective enrichment is key for slow-growing bacteria. Leverage the metabolic predictions from your MAG to create a selective advantage for your target.

- Use Substrate-Specific Selection: Your MAG's annotation may reveal a unique carbon or nitrogen source utilization potential, such as the ability to degrade complex polysaccharides (e.g., chitin, alginate) or specific aromatic compounds. Use that compound as the sole carbon source in your medium [31].

- Implement Chemical Inhibitors: Add low concentrations of antibiotics or other inhibitors that target common contaminants but not your organism, based on predicted resistance genes (e.g., vancomycin for Gram-negative selection).

- Employ Physical Separation Techniques: Use methods like floating filter cultivation or microcapsule-based cultivation to physically separate slow-growing cells from faster-growing competitors, allowing isolated microcolonies to form [32].

FAQ 3: I suspect my target marine bacterium requires a symbiotic partner. How can I design a co-culture experiment?

Answer: Dependency on other microbes is a major reason for unculturability [31]. A targeted co-culture strategy can overcome this.

- Identify Potential Partners: Analyze your MAG for missing metabolic pathways. Then, screen metagenomic data from the same sample for other microbes that could fill these gaps (e.g., a vitamin producer or a partner that degrades a complex substrate into a simpler one your target can use).

- Design a Cross-Feeding Setup: A straightforward method is to grow the suspected helper strain on one side of a semi-solid medium plate and inoculate your target bacterium on the other, allowing metabolites to diffuse. Alternatively, use a membrane system where the two strains are separated by a permeable membrane.

- Start with a Community Inoculum: If specific partners are unknown, use a highly diluted sample as your inoculum in a medium designed for your target. This can result in microcosms where the necessary cross-feeding partners are present but diversity is low enough to eventually isolate the target.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Defined Medium from MAG-predicted Metabolism

This protocol details the creation of a defined medium based on genomic evidence.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Artificial Seawater Base | Provides essential ions and trace metals (Na+, Mg2+, K+, Ca2+, Cl-, SO42-). |

| Carbon Source Mix | Based on MAG prediction (e.g., sodium succinate, N-acetylglucosamine, chitin). |

| Vitamin & Cofactor Supplement | A defined mix of B vitamins, heme, etc., tailored to predicted auxotrophies. |

| Amino Acid Supplement | A defined mix of specific amino acids if biosynthetic pathways are incomplete. |

| Reducing Agents | For anaerobes (e.g., cysteine-HCl, thioglycolate). |

Methodology:

- Reconstruct Metabolism: Use tools like KEGG and MetaCyc to map the metabolic pathways in your MAG. Identify complete pathways for energy metabolism and incomplete ones for biomass building blocks [31].

- Formulate Base Medium: Start with a defined artificial seawater recipe.

- Add Carbon and Energy Sources: Incorporate the specific carbon source(s) your MAG indicates the organism can utilize (e.g., 5-10 mM).

- Supplement for Gaps: Add the specific amino acids, vitamins, and nucleobases for which biosynthetic pathways are missing, using Table 1 as a guide.

- pH and Redox Adjustment: Adjust the pH to match the source environment (e.g., pH 7.5-8.2 for seawater). For anaerobic microbes, add reducing agents and purge the medium with N2/CO2.

- Sterilize and Inoculate: Filter-sterilize the medium (0.22 µm) to avoid heat-degrading supplements. Inoculate and monitor growth.

Protocol 2: Metagenome-Guided Enrichment and Isolation using Floating Filters

This protocol uses physical separation to isolate slow-growing microbes [32].

Methodology:

- Prepare Enrichment Broth: Create a medium tailored to your target organism's predicted metabolism, as per Protocol 1.

- Inoculate and Pre-enrich: Inoculate the broth with a small amount of the environmental sample (e.g., marine sponge tissue). Incubate with mild shaking for 24-48 hours.

- Transfer to Floating Filter: Aseptically pipet a portion of the pre-enrichment culture onto a sterile filter membrane (e.g., 0.45 µm pore size) floating on a rich, non-selective medium (e.g, Marine Agar broth).

- Incubate for Microcolony Formation: The filter allows diffusion of nutrients and signaling molecules from the underlying medium while physically separating slow-growing cells from fast-growing planktonic cells in the pre-enrichment. Incubate for several weeks.

- Pick and Sub-culture: Periodically examine the filter under a microscope for microcolony formation. Pick individual microcolonies and transfer them to fresh, targeted medium to establish a pure culture.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic process of going from metagenomic data to a purified isolate.

Metagenome-Guided Cultivation Workflow

The following table summarizes the primary data types and how they inform specific cultivation design strategies.

Table 2: Metagenomic Data Informs Cultivation Strategy

| Metagenomic Data Type | Information Gained | Corresponding Cultivation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| 16S/18S rRNA Gene | Phylogenetic identity, diversity profile. | Guides initial media choice based on known relatives. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) | Metabolic potential, biosynthetic capabilities, auxotrophies [31]. | Enables design of defined/semi-defined media; suggests selective substrates. |

| Metatranscriptome | Active metabolic pathways & community interactions in situ [31]. | Indicates optimal substrates & conditions; identifies key cross-feeding dependencies. |

| Single-Amplified Genome (SAG) | Genome from a single, uncultured cell. | Provides a clean metabolic blueprint for media design, free of community contamination. |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

As the field evolves, new technologies are being integrated with metagenomics to further break down cultivation barriers. For instance, AI-powered tools are now being developed to assist in complex biological design tasks, a concept that could be adapted to predict optimal cultivation conditions from complex genomic data [33]. Furthermore, targeted function-guided screening of metagenomic libraries expressed in heterologous hosts remains a powerful, though challenging, approach to access natural products from uncultured marine microbes [34] [35].

Cultivating anaerobic microorganisms is a cornerstone of environmental and biomedical research, yet it presents a unique set of challenges due to the oxygen sensitivity of these organisms. Overcoming these challenges is particularly crucial within the context of marine microbiology, where an estimated over 99% of microorganisms have not been cultured under standard laboratory conditions [36]. These "microbial dark matter" represent an immense reservoir of unexplored biodiversity with potential for novel bioactive substances, including new antibiotics and anti-tumor agents [36]. The development and precise implementation of specialized anoxic cultivation techniques, such as the Hungate method, are therefore not merely technical exercises but fundamental to expanding our understanding of complex marine ecosystems and unlocking their biotechnological potential. This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers navigating the complexities of anaerobic cultivation, offering troubleshooting solutions and detailed protocols to overcome the persistent limitations in marine microbial research.

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in Anaerobic Cultivation

Q1: Why is my anaerobic culture showing no growth, and how can I troubleshoot this?

A systematic approach is essential for diagnosing the absence of growth in anaerobic cultures. Please consult the table below for common issues and solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for No Growth in Anaerobic Cultures

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Contamination | Check for pink discoloration in media containing resazurin (a redox indicator) [37]. | Use pre-reduced anaerobically sterilized (PRAS) media. Ensure all procedures are conducted within an anaerobic chamber or using anaerobic jars [37]. |

| Incorrect Media Composition | Verify that all necessary nutrients and electron acceptors are present. | Use specialized media like reinforced clostridial or peptone yeast extract broth. Supplement with vitamin K1, hemin, or blood as required by your specific organism [37]. |

| Inadequate Sample Collection & Transport | Review how the specimen was collected and stored. | Collect samples with needle/syringe and immediately inject into anaerobic transport vials containing oxygen-free gas to prevent deterioration [38] [39]. |

| Overlooked Long Lag Phases | Maintain cultures for an extended period. | Be aware that some anaerobic enrichments can have lag phases of 6 months or longer before showing visible growth [40]. |

Q2: What are the fundamental differences between the Hungate Technique and the use of an anaerobic chamber?

The choice between these two primary methods depends on the required stringency, workflow volume, and cost considerations.

Table: Comparison of Primary Anaerobic Cultivation Methods

| Feature | Hungate Tube Technique | Anaerobic Chamber |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Creates an oxygen-free environment in individual tubes via gassing and sealing [40]. | An enclosed glove box filled with an oxygen-free gas mixture (e.g., Nâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚) [37]. |

| Best For | Culturing extremophiles and strict anaerobes; broth cultures; long-term storage [37]. | High-throughput work; processing multiple samples or agar plates simultaneously [37]. |

| Key Advantage | Superior for maintaining strict anoxic conditions, especially in pressurized tubes (Balch tubes) [40]. | Convenience and efficiency for manipulating cultures and performing experiments without exposure to oxygen [37]. |

| Potential Limitation | Can be labor-intensive and requires technical skill for gassing operations [40]. | Higher initial cost; potential for oxygen leakage over time [37]. |

Q3: My digester or enrichment culture is producing excessive foam/scum. What could be the cause?

Foaming is a common operational issue often linked to an imbalance in the microbial community or process parameters.

- Potential Causes: This can result from improper mixing, nutrient deficiencies, or an excessive organic loading rate that leads to the accumulation of surface-active compounds [41].

- Corrective Actions: Regularly inspect and maintain agitators to ensure consistent mixing. Analyze your feedstock for sudden compositional shifts and avoid overloading the system [41]. If foaming persists, it may indicate a deeper imbalance requiring professional diagnostic support.

Essential Protocols for Anaerobic Cultivation

The Hungate Technique for Strict Anaerobes

The Hungate technique, a cornerstone of anaerobic microbiology, relies on the principle of excluding oxygen by using gassing to create and maintain an anoxic environment [40].

Detailed Methodology:

- Media Preparation and Reduction: Prepare media by boiling to drive off dissolved oxygen. During cooling and dispensing, continuously sparge the media with an oxygen-free gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or a Nâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ mix). Add a reducing agent, such as cysteine-HCl or sodium sulfide, which chemically binds any residual oxygen [37] [40]. The indicator resazurin (0.0001%) is used to visually confirm anoxic conditions; it turns pink in the presence of oxygen and is colorless when reduced [37].

- Dispensing under Gas: Dispense the pre-reduced media into Hungate tubes (screw-capped tubes with butyl rubber septa) or Balch tubes (for crimped aluminum seals) while maintaining a constant stream of oxygen-free gas over the medium [37] [40].

- Sterilization: Autoclave the tubes with caps loosely tightened, then tighten fully after sterilization once the tubes have cooled.

- Inoculation: Inoculate using a syringe and needle to pierce the rubber septum, ensuring the tip of the needle is within the gas stream to avoid introducing oxygen. For liquid inoculum, the medium can be briefly flushed with oxygen-free gas via a second needle [40].

- Incubation: Incubate the tubes at the appropriate temperature without agitation for strict anaerobes.

Diagram: Workflow of the Classic Hungate Tube Technique

Cultivation of Dormant and "Unculturable" Marine Bacteria

A significant challenge in marine microbiology is that many bacteria are in a dormant or "viable but nonculturable" (VBNC) state, requiring specific resuscitation signals [36].

Detailed Methodology:

Simulating the Natural Environment:

- Low-Nutrient Media: Use diluted nutrients or natural seawater-based media to avoid shocking oligotrophic bacteria [36] [42]. Studies have achieved cultivation efficiencies up to 45% using standard marine agar, far exceeding the traditional 1% dogma [42].

- Extended Incubation: Incubate plates for several weeks to months to allow slow-growing bacteria to form colonies [42].

Application of Resuscitation Stimuli:

- Signaling Molecules: Add low concentrations of resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpfs), quorum-sensing molecules, or other signaling compounds to the medium to stimulate the exit from dormancy [36].

- Metabolic Cofactors: Supplement media with catalase (to degrade Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) or siderophores (for iron acquisition) to alleviate environmental stresses [36].

- Co-culture: Cultivate target strains together with helper bacteria that provide essential metabolites or cross-protection, mimicking natural microbial interactions [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful anaerobic cultivation depends on the use of specialized reagents and materials to create and maintain an oxygen-free environment.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Anaerobic Work

| Item | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Resazurin Indicator | A redox-sensitive dye that turns pink in the presence of oxygen, providing a visual check of anoxic conditions [37]. | Quality control for media preparation in all anaerobic systems. |

| Cysteine-HCl / Sodium Sulfide | Reducing agents that chemically scavenge trace oxygen from culture media, creating a low redox potential [37] [40]. | Essential component of PRAS media for the Hungate technique and anaerobic chambers. |

| Butyl Rubber Stoppers | Made of material with very low oxygen permeability, used to seal Hungate tubes or serum bottles [37] [40]. | Maintaining long-term anaerobic conditions in tube cultures. |

| Pre-reduced Anaerobically Sterilized (PRAS) Media | Media that are boiled, gassed, sealed, and autoclaved to ensure they are oxygen-free upon receipt [37]. | Gold standard for ensuring media is not a source of oxygen contamination. |

| Anaerobic Transport Vials | Vials containing an oxygen-free gas mix (COâ‚‚ or Nâ‚‚) for clinical or environmental sample transport [38] [39]. | Preserving viability of anaerobic specimens from the field/clinic to the lab. |

| Anoxomat / Anaerobic Jars | Systems that automatically evacuate air and replace it with precise anaerobic gas mixtures from jars or pouches [37]. | A convenient method for incubating a small number of agar plates. |

| 3-Methyldecanoyl-CoA | 3-Methyldecanoyl-CoA, MF:C32H56N7O17P3S, MW:935.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stearyl arachidonate | Stearyl arachidonate, MF:C38H68O2, MW:556.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Techniques: Bridging to Marine Microbial Dark Matter

Overcoming the "unculturable" dogma requires innovative methods that more closely mimic the natural environment. The following diagram and table summarize two such advanced approaches.

Diagram: Advanced Cultivation Strategies for Challenging Microbes

Table: Advanced Cultivation Methods for Marine Microorganisms

| Technique | Core Principle | Protocol Summary | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Cultivation (e.g., iChip, Diffusion Chambers) | Cells are confined in a device with a semi-permeable membrane, which is then returned to the natural environment, allowing diffusion of chemical signals and nutrients [36]. | 1. Dilute environmental sample. 2. Load into multiple miniature diffusion chambers. 3. Seal chambers and incubate in the original habitat or a simulated one. 4. Retrieve and recover grown cells on lab media [36]. | Has enabled the cultivation of previously uncultivable marine bacteria, leading to the discovery of new antibiotics and metabolites [36]. |

| Microfluidic Droplet Cultivation | Encapsulates single microbial cells in nanoliter-sized droplets, which function as independent bioreactors, enabling high-throughput cultivation [36]. | 1. Generate water-in-oil droplets containing a single cell and growth medium. 2. Incubate the emulsion. 3. Monitor for growth within droplets. 4. Break droplets to retrieve viable cultures of interest [36]. | Ideal for cultivating rare bacteria from marine samples and for performing ultra-miniaturized enzyme or antibiotic screening [36]. |

Optimizing Growth and Yield: Strategic Frameworks for Stubborn Microbes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons for the failure to culture marine microorganisms in the laboratory? The primary challenge is known as the "great plate count anomaly," where standard microbiological techniques typically cultivate less than 1% of the bacterial diversity observed in marine samples through microscopy [2] [42]. Failure often occurs because laboratory conditions disrupt essential environmental factors, including:

- Disruption of Microbial Consortia: Many marine bacteria rely on metabolic by-products or signaling molecules from other organisms in their natural consortia. Standard pure culture techniques isolate cells from these necessary interactions [2].

- Incorrect Nutrient Profiles: The use of overly rich media or inappropriate substrate combinations can inhibit growth, especially for oligotrophic bacteria adapted to low-nutrient conditions in the open ocean [2].

- Absence of Essential Signals: Laboratory media may lack specific chemical or physical signals, such as those for quorum sensing, that are required to initiate growth [2].

FAQ 2: Beyond simple media supplementation, what advanced strategies can improve cultivation yields? Moving beyond basic nutrient addition, successful strategies focus on mimicking the natural marine environment more closely:

- High-Throughput Techniques: Methods like dilution-to-extinction in low-nutrient media help isolate slow-growing bacteria by reducing competition from fast-growing species [24] [43].

- In Situ Cultivation: Devices like the iChip (isolation chip) allow microbes to be cultured in their natural habitat by using semi-permeable membranes that permit the diffusion of environmental chemicals and growth factors while containing individual cells [24].