Deterministic Drivers and Ecological Assembly of Anammox Bacterial Communities in Wastewater Treatment Systems

This article synthesizes current research on the ecological mechanisms governing the assembly of anammox bacterial communities, a crucial process for sustainable nitrogen removal.

Deterministic Drivers and Ecological Assembly of Anammox Bacterial Communities in Wastewater Treatment Systems

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the ecological mechanisms governing the assembly of anammox bacterial communities, a crucial process for sustainable nitrogen removal. We explore the fundamental principles of stochastic versus deterministic assembly, highlighting recent evidence that deterministic processes, driven by factors like substrate limitation and filtration dynamics, predominantly shape functional biofilms. The review details methodological advances in bioreactor technology, such as Anammox-MBRs and DMBRs, that leverage these ecological principles for robust process application. We further address operational challenges, including sensitivity to temperature and emerging pollutants, and present optimization strategies grounded in microbial ecology. Finally, we compare anammox with other nitrogen-removal pathways, validating its role in the global nitrogen cycle and its potential for creating energy-positive wastewater treatment systems, with implications for environmental biotechnology.

The Ecological Blueprint: Unraveling Core Principles of Anammox Community Assembly

The structure and function of any microbial ecosystem are fundamentally shaped by its assembly processes—the mechanisms that determine which species colonize, persist, and interact within a community. These processes are broadly categorized as either deterministic or stochastic. Deterministic processes encompass predictable selection pressures imposed by abiotic environmental factors (e.g., pH, temperature, substrate availability) and biotic interactions (e.g., competition, facilitation). In contrast, stochastic processes involve unpredictable elements of ecological drift, random birth-death events, and probabilistic dispersal [1]. In engineered biological systems like anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) reactors, understanding the balance between these forces is crucial for optimizing system performance, enhancing functional stability, and steering microbial communities toward desired outcomes [2] [3].

The study of these ecological drivers is particularly salient in anammox bacterial community assembly research. Anammox bacteria, central to a highly efficient biological nitrogen removal technology, are characterized by slow growth and sensitivity to environmental fluctuations [2]. Understanding whether their communities assemble primarily through deterministic selection or stochastic chance provides critical insights for managing biomass retention, preventing process failure, and improving nitrogen removal efficiency in wastewater treatment applications [2] [4] [5].

Theoretical Framework of Stochastic and Deterministic Processes

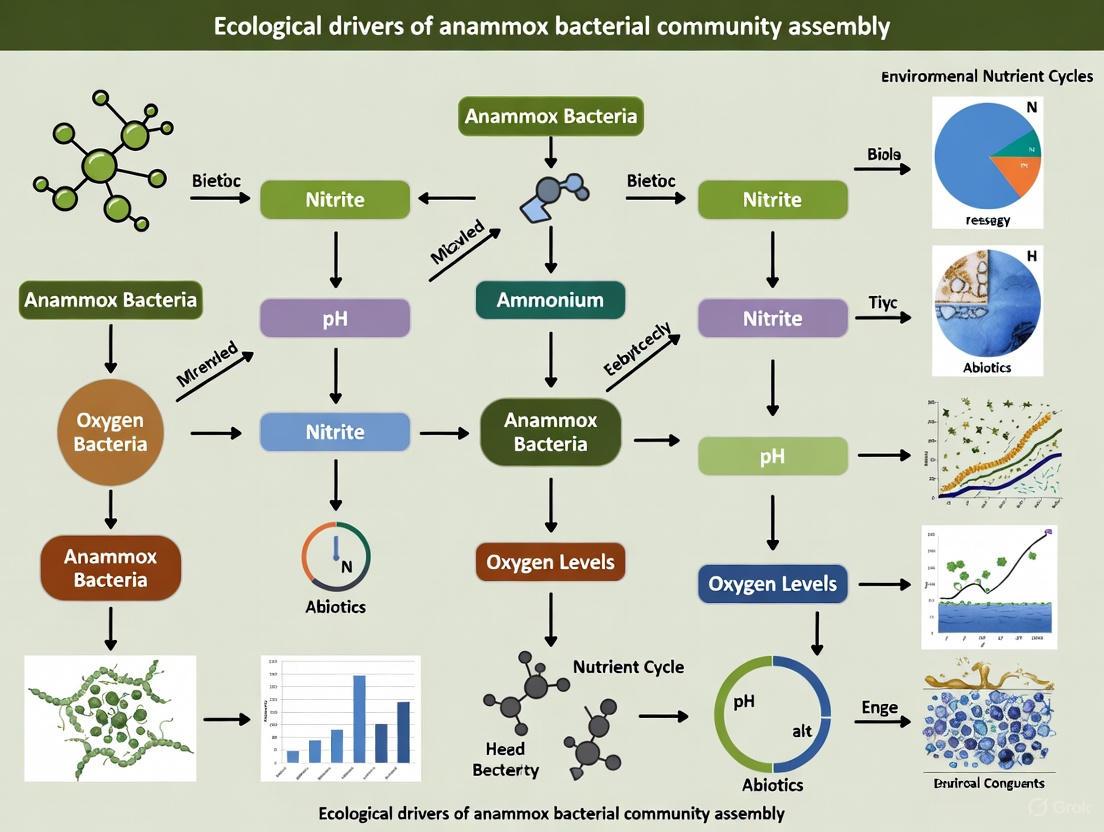

The following diagram illustrates the key processes and their relationships in microbial community assembly.

Deterministic Processes

Deterministic processes result in predictable community composition based on specific environmental conditions and species interactions.

- Homogeneous Selection: This occurs when consistent environmental conditions across habitats select for the same set of microbial species, leading to communities that are more similar than would be expected by chance. In anammox systems, this can be driven by stable operating parameters such as substrate type and concentration, temperature, and pH [2] [3].

- Heterogeneous Selection: Opposite to homogeneous selection, this process dominates when environmental conditions vary between habitats, selecting for different microbial populations and resulting in communities that are more dissimilar than expected by chance [3].

Stochastic Processes

Stochastic processes introduce an element of chance into community assembly, making outcomes less predictable.

- Dispersal Limitation: This arises when geographic or physical barriers prevent microbial taxa from reaching a suitable habitat. In engineered granular sludge systems, the limited microbial exchange between individual granules is a classic example, contributing to high variability between granules even within the same reactor [6].

- Ecological Drift: This refers to random changes in species abundance due to chance birth-death events, whose effects are more pronounced in small populations and can lead to random loss of species from a community [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Assembly Processes in Anammox Systems

The relative influence of stochastic and deterministic processes varies significantly across different anammox reactor configurations and microhabitats. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Contributions of Assembly Processes in Anammox Systems

| System Type | Community Component | Deterministic Contribution | Stochastic Contribution | Key Deterministic Factor(s) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anammox DMBR | Functional Membrane Biofilm | Dominant (Primarily Homogeneous Selection) | Lower | Limited nitrogen substrates, low filtration permeate drag force | [2] |

| Anammox Granules (Swine WWTP) | Whole Community | 10.20-26.47% | 71.51-89.75% (Dispersal Limitation) | Complex wastewater composition | [6] |

| Anammox Granules (Lab-scale) | Whole Community | Lower | Dominant (Dispersal Limitation) | N/A | [6] |

| Anaerobic Digestion Granules | Floating/Settled Biomass | Homogeneous Selection primary mechanism | Dispersal processes also contributed | Temperature shift, flotation event | [1] |

| Cold-Rolling Wastewater Treatment | Activated Sludge | Deterministic dominant | Stochastic also present | Regional environmental factors, wastewater composition | [3] |

The data reveals a critical pattern: the assembly of anammox bacteria is highly context-dependent. While deterministic processes often govern specific functional niches like membrane biofilms, stochasticity, particularly dispersal limitation, frequently dominates in suspended or granular sludge communities [2] [6]. Furthermore, the balance can shift under different conditions. For instance, anammox bacteria were found to be predominantly affected by homogeneous selection under high substrate-loading conditions, but by drift under low substrate-loading [2].

Methodological Approaches for Quantifying Assembly

Experimental Workflow for Community Assembly Analysis

A typical research pipeline for investigating these processes involves sample collection, molecular analysis, and ecological inference, as detailed in the workflow below.

Key Analytical Frameworks

- Null Model Analysis: This is a cornerstone method. It compares observed phylogenetic diversity (e.g., β-diversity) to a distribution of values expected under a null hypothesis of random assembly. The β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) is a key metric derived from this analysis. |βNTI| > 2 indicates a dominant role of deterministic processes (homogeneous selection if βNTI < -2, or heterogeneous selection if βNTI > +2), while |βNTI| < 2 suggests a significant role for stochastic processes [2] [6] [3].

- Neutral Community Model: This model predicts species occurrence and abundance based on random immigration and ecological drift. A good fit between observed data and the neutral model suggests stochastic assembly is dominant. Significant deviations from the model indicate the influence of deterministic selection [6].

- Co-occurrence Network Analysis: This infers potential microbial interactions based on correlation patterns. The Zi-Pi plot derived from network analysis classifies taxa into ecological roles (e.g., specialists, generalists), providing insights into niche-based (deterministic) versus stochastic influences. Increased modularity in networks can indicate a community's response to stress, such as nitrogen-loading fluctuations [4].

Research Reagents and Materials for Assembly Studies

The following table catalogs essential reagents, materials, and tools used in experimental anammox community assembly research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Anammox Assembly Studies

| Category | Item | Technical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreactor Components | Polyurethane Porous Material / PVA Gel Beads | Serves as a biofilm carrier; provides high surface area for bacterial attachment, retains biomass, creates distinct microhabitats for studying assembly [7]. |

| Dynamic Membrane Bioreactor (DMBR) | Creates a functional membrane biofilm; allows investigation of assembly under low permeate drag force and substrate limitation [2]. | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | DNA/RNA Co-extraction Kits | Simultaneous extraction of genomic DNA (for community structure) and RNA (for active community) from complex samples like granules [1]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers (e.g., 338F/806R) | Amplifies the V3-V4 hypervariable region for high-throughput sequencing and microbial community profiling [7]. | |

| Illumina MiSeq Platform | High-throughput sequencing platform for 16S rRNA gene amplicons to characterize microbial community composition [7]. | |

| Analytical Software & Tools | PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States; predicts functional potential of microbial communities from 16S rRNA gene data [4]. |

| I-sanger Cloud Platform / QIIME2 | Bioinformatic platforms for processing and analyzing high-throughput sequencing data, including OTU/ASV picking and diversity analyses [7]. | |

| R (with vegan, picante, etc.) | Statistical computing environment for performing null model analysis, neutral model fitting, and other ecological statistical tests [6] [3]. |

Implications for Anammox Process Optimization

Understanding community assembly rules provides a scientific basis for manipulating anammox systems. When deterministic processes dominate, operators can steer the community by controlling key selective pressures like substrate loading and availability. For instance, niche differentiation among anammox genera can be exploited by creating selective microhabitats; Candidatus Kuenenia, for example, shows preferential enrichment in membrane biofilms with limited nitrogen substrates [2]. Furthermore, the knowledge that biofilms can protect anammox bacteria from inhibitory conditions like low pH suggests that using biofilm reactors is a deterministic strategy to enhance process resilience [5].

Conversely, in systems where stochastic dispersal limitation is a major factor (e.g., in granular sludge), strategies like controlled mixing or bioaugmentation with specific consortia can be employed to overcome random variability and ensure the presence of key functional guilds [6]. Managing the nitrogen-loading rate is critical, as both excessive loading and starvation can cause performance deterioration and alter anammox bacterial abundance, indicating a shift in the dominant assembly processes under stress [4].

Key Anammox Genera and Their Distinct Physiological Niches

The discovery of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the global nitrogen cycle, challenging the long-held paradigm that denitrification was the sole significant pathway for fixed nitrogen removal from ecosystems [8] [9]. These specialized microorganisms perform the anammox reaction, oxidizing ammonium using nitrite as an electron acceptor under anoxic conditions to yield dinitrogen gas [8]. This process provides a more environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional nitrogen removal technologies, with lower energy requirements, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and no need for external carbon sources [10]. Beyond engineered systems, anammox bacteria are now recognized as cornerstone contributors to nitrogen loss in natural environments, accounting for 10-40% of all nitrogen gas production in marine settings [8].

A comprehensive understanding of anammox ecology requires moving beyond treating these organisms as a monolithic functional group. Research has revealed significant genomic and physiological diversity among anammox bacteria, which has led to niche differentiation and distinct distribution patterns across environmental gradients [8] [10] [11]. This technical guide examines the key anammox genera—Candidatus Brocadia, Candidatus Kuenenia, Candidatus Jettenia, and Candidatus Scalindua—detailing their unique physiological characteristics and the ecological mechanisms governing their community assembly. Framed within the context of ecological drivers, this review synthesizes current knowledge on how deterministic and stochastic processes shape anammox bacterial communities across diverse ecosystems.

Physiological Diversity of Key Anammox Genera

Anammox bacteria belong to a monophyletic group within the phylum Planctomycetota [10]. To date, six genera have been identified: Candidatus Brocadia, Candidatus Kuenenia, Candidatus Jettenia, Candidatus Scalindua, Candidatus Anammoximicrobium, and Candidatus Anammoxoglobus [9]. The first four genera represent the most extensively studied and widely distributed, each exhibiting distinct physiological traits and habitat preferences that underpin their ecological niches.

Table 1: Key Physiological Characteristics and Habitat Preferences of Major Anammox Genera

| Genus | Common Environments | Temperature Optima | Salinity Tolerance | Notable Physiological Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca. Brocadia | WWTPs, freshwater sediments, terrestrial ecosystems [10] [11] | Mesophilic (~30-40°C) [10] | Low to moderate [10] | Relatively higher growth rates; adapts to broader environmental conditions [10] |

| Ca. Kuenenia | WWTPs, engineered systems [10] | Mesophilic [10] | Low [10] | Dominates biofilm configurations; exhibits niche differentiation in substrate-limited conditions [2] |

| Ca. Jettenia | WWTPs, some freshwater environments [10] | Mesophilic [10] | Low [10] | Greater environmental specificity; more sensitive to unfavorable conditions [10] |

| Ca. Scalindua | Marine, estuarine sediments [11] [9] | Broader range including lower temperatures [11] | High (marine) [11] | Dominant in marine ecosystems; phylogenetically diverse; acidophilic amino acid bias in proteome [8] [11] |

Table 2: Nutrient Uptake Affinities and Metabolic Partnerships of Anammox Genera

| Genus | Substrate Affinity (NHâ‚„âº/NOâ‚‚â») | Common Metabolic Partners | Interaction Type with Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca. Brocadia | Varies between species [2] | Denitrifiers, AOB [10] | Competition for nitrite [6] |

| Ca. Kuenenia | Varies between species [2] | AOB, NOB [10] | Cooperative (NO provision) [10] |

| Ca. Jettenia | Not well characterized | Dependent on vitamin producers [10] | Cross-feeding (vitamins) [10] |

| Ca. Scalindua | Adapted to low nutrient marine conditions [11] | Unknown in marine environments | Keystone role in co-occurrence networks [11] |

Genomic and Proteomic Adaptations

Genomic analyses reveal significant adaptations among anammox genera that correlate with their environmental preferences. Halophilic and non-halophilic species show distinct genetic profiles, with halophiles possessing a unique set of genes absent in other species [8]. Proteomic investigations further demonstrate evolutionary divergence, with halophilic strains like Ca. Scalindua exhibiting a bias toward acidic amino acids and under-representation of cysteine, adaptations that enhance protein stability and function under high salinity [8]. These fundamental differences in genomic makeup and proteomic composition underscore the deep evolutionary adaptations that have enabled anammox bacteria to colonize diverse habitats.

Community Assembly Processes in Anammox Ecosystems

The assembly of anammox bacterial communities is governed by a complex interplay of deterministic (niche-based) and stochastic (neutral) processes, whose relative importance varies across environmental contexts and ecosystem types.

Deterministic versus Stochastic Assembly

Deterministic processes occur when environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, substrate availability) or biological interactions (e.g., competition, cooperation) impose selection pressures that favor specific taxa. In contrast, stochastic processes arise from random birth-death events, dispersal limitations, and ecological drift [2] [6].

In engineered systems like wastewater treatment plants, deterministic factors often exert strong influences on community composition. Studies of anammox dynamic membrane bioreactors (DMBRs) have demonstrated that deterministic assembly prevails in membrane biofilms, particularly under conditions of limited nitrogen substrates and low filtration permeate drag force [2]. This deterministic selection leads to niche differentiation, with different anammox genera preferentially colonizing specific microhabitats within reactors. For instance, Ca. Kuenenia shows preferential enrichment on membrane biofilms, while Ca. Brocadia and Ca. Jettenia dominate in suspended sludge fractions [2].

Conversely, stochastic processes frequently dominate in granular sludge systems. Analysis of 200 anammox granules from full-scale and lab-scale reactors revealed that dispersal limitation accounted for 71.51-89.75% of community assembly, indicating limited microbial exchange between granules [6]. This stochastic dominance results in high heterogeneity among individual granules, despite functional bacteria maintaining high relative abundance at the system level.

Environmental Filters Shaping Anammox Communities

Key environmental factors act as deterministic filters that shape anammox community composition:

Temperature: Temperature regimes significantly influence anammox bacterial activity and stress response. Under dissolved oxygen (DO) perturbations, anammox biofilms at 20°C and 14°C exhibited divergent transcriptional responses, with community-wide gene expression differing significantly depending on the temperature regime [12]. Lower temperatures generally reduce metabolic activity but may confer protection against oxygen stress [12].

Substrate Availability: Nitrogen substrate concentrations and ratios strongly influence anammox community composition. Variations in nitrogen substrate affinities among anammox genera drive population shifts in reactors, with substrate-limited conditions promoting deterministic assembly [2]. Different anammox species possess distinct half-saturation constants (Km) for ammonium and nitrite, creating niche differentiation along substrate concentration gradients [2].

Salinity: Salinity serves as a powerful environmental filter, clearly separating marine-adapted Ca. Scalindua from freshwater genera like Ca. Brocadia and Ca. Kuenenia [11] [9]. Estuarine environments with salinity gradients demonstrate progressive shifts in anammox community composition along the salinity continuum.

Dissolved Oxygen: DO concentrations represent a critical determinant for anammox distribution, as these strictly anaerobic bacteria exhibit high sensitivity to oxygen. However, different species show varying degrees of oxygen tolerance, creating microhabitat specialization within anoxic zones and biofilms [12].

The following diagram illustrates the ecological processes and environmental factors governing anammox community assembly across different ecosystems:

Diagram Title: Ecological Framework of Anammox Community Assembly

Methodologies for Studying Anammox Ecology

Molecular Techniques for Community Analysis

Advanced molecular techniques have revolutionized our ability to characterize anammox community structure and function:

High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS): 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing enables comprehensive profiling of anammox bacterial diversity and community composition across environmental samples [11] [9]. This approach has revealed unprecedented diversity within anammox communities, including the discovery of rare taxa that play crucial ecological roles.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Target gene quantification (e.g., 16S rRNA and hzo genes) provides accurate measurements of anammox bacterial abundance in environmental samples [9]. This method has demonstrated anammox abundances ranging from 2.34×10ⵠto 9.22×10ⵠcopies/g sediment in estuarine systems like Hangzhou Bay [9].

Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics: Shotgun metagenomic sequencing reveals the functional potential of anammox communities, while metatranscriptomics provides insights into gene expression patterns under different environmental conditions [12]. These approaches have revealed that different anammox species and key biofilm taxa display divergent transcriptional responses to environmental stressors like DO perturbations [12].

Table 3: Molecular Methods for Anammox Community Characterization

| Method | Target | Application in Anammox Research | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions | Diversity assessment, community composition [11] [9] | Identification of six anammox genera; spatial distribution patterns [9] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Functional genes (hzo) and 16S rRNA | Absolute abundance quantification [9] | Anammox abundance correlates with environmental factors [9] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Total community DNA | Functional potential analysis [12] | Identification of halophilic adaptation genes [8] |

| Metatranscriptomic Sequencing | Total community RNA | Gene expression profiling [12] | Stress response mechanisms to DO and temperature [12] |

Experimental Approaches for Physiological Characterization

Controlled laboratory studies have been instrumental in elucidating the physiological characteristics of different anammox genera:

Bioreactor Studies: Continuous-flow bioreactors with precise environmental control enable investigation of growth kinetics, substrate affinities, and inhibition thresholds under defined conditions [2] [12]. These systems have revealed fundamental differences in nutrient uptake kinetics among anammox genera.

Disturbance Experiments: Purposeful application of environmental stressors (e.g., oxygen pulses, temperature shifts) followed by monitoring of process performance and microbial response provides insights into functional resilience and adaptation mechanisms [12]. Such experiments have demonstrated that temperature regime modulates the transcriptional response of anammox bacteria to oxygen shocks [12].

Isotope Tracer Techniques: ¹âµN-labeled substrate incubations allow quantification of anammox process rates in both natural and engineered systems, enabling researchers to link community composition with biogeochemical function [11].

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for investigating anammox community ecology:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Anammox Ecology Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Anammox Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Sets (Brod541F/Amx820R) | Amplification of anammox bacterial 16S rRNA genes [11] | Diversity assessment in coastal sediments [11] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (FastDNA SPIN) | High-quality DNA extraction from complex matrices [11] | Nucleic acid isolation from sediment samples [11] |

| Polycarbonate Incubation Bottles | Contamination-free experimental vessels [13] | Deep-water addition phytoplankton bloom experiments [13] |

| Liquid Waveguide Spectrophotometry | Sensitive nanomolar nutrient concentration measurement [13] | Precise quantification of nutrient drawdown ratios [13] |

| CIE Lab* Color Space Analysis | Digital quantification of anammox sludge chromaticity [14] | Correlation between sludge color and metabolic activity [14] |

| SBR Bioreactor Systems | Controlled cultivation of anammox biofilms [12] | Investigation of temperature and DO disturbance effects [12] |

| Dynamic Membrane Bioreactors (DMBRs) | Biomass retention and functional biofilm study [2] | Analysis of niche differentiation in membrane biofilms [2] |

| ATP (Standard) | ATP (Standard), MF:C10H16N5O13P3, MW:507.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| XST-14 | XST-14, MF:C16H21NO4, MW:291.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Ecological Interactions and Network Dynamics

Anammox bacteria do not function in isolation but rather as embedded members of complex microbial communities. Network analysis of co-occurrence patterns has revealed intricate relationships between anammox bacteria and associated microbial taxa, with predominantly negative correlations (60.00-90.91% of connections) observed between anammox bacteria and heterotrophic populations in granular sludge systems [6]. These negative correlations suggest resource competition, particularly for nitrite, between these functional groups.

In contrast, some anammox genera engage in cooperative interactions. Recent research has identified a novel nitric oxide (NO) cross-feeding mechanism that enhances nitrogen removal performance when strengthened [10]. Additionally, anammox bacteria depend on metabolic partnerships with other community members for essential nutrients; for instance, some anammox bacteria rely on other heterotrophic bacteria to provide essential amino acids and vitamins for growth and development [10].

The role of rare species in maintaining ecological stability has gained increasing recognition. In coastal sediments, rare anammox taxa appear more susceptible to dispersal limitations and environmental selection but play crucial roles in maintaining the ecological stability of anammox bacterial communities [11]. These rare species may serve as a reservoir of functional resilience, potentially becoming more prominent under changing environmental conditions.

The ecological distribution and community assembly of anammox bacteria are governed by a complex interplay between phylogenetic constraints, physiological adaptations, and environmental selection. The major anammox genera—Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Kuenenia, Ca. Jettenia, and Ca. Scalindua—each occupy distinct physiological niches shaped by their evolutionary histories and adaptive capabilities. While Ca. Brocadia and Ca. Kuenenia dominate engineered systems with their broader tolerance ranges and faster growth potential, Ca. Scalindua maintains its supremacy in marine environments through specialized salt adaptation mechanisms.

The relative importance of deterministic versus stochastic processes in community assembly varies across ecosystem types, with deterministic selection predominating in controlled engineered systems and under strong environmental gradients, while stochastic processes frequently govern granular sludge communities and natural environments with moderate selection pressures. This understanding of anammox ecology provides a critical foundation for optimizing nitrogen removal in engineered systems and predicting nitrogen cycling responses to environmental change in natural ecosystems.

Future research directions should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches to link community composition with function, elucidating the mechanisms of rare species contributions to ecosystem resilience, and developing predictive models that incorporate both ecological theory and microbial physiology to forecast anammox community dynamics under changing environmental conditions.

Within the framework of ecological drivers governing anammox bacterial community assembly, environmental filters act as deterministic forces that select for specific functional traits, ultimately shaping community structure and ecosystem function. The anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process, performed by specialized bacteria within the phylum Planctomycetota, represents a crucial microbial pathway for nitrogen removal in both natural and engineered ecosystems. The efficacy of this process is fundamentally governed by key environmental parameters—notably substrate concentration, temperature, and pH—which filter the community composition and metabolic activity of anammox bacteria (AnAOB). This technical guide synthesizes current research on how these deterministic drivers influence anammox ecology and performance, providing a structured analysis of quantitative relationships, underlying mechanisms, and methodological approaches for their investigation. The insights herein are pivotal for predicting anammox community dynamics and optimizing their application in wastewater treatment and biogeochemical cycling models.

Substrate Dynamics and Nitrogen Removal Stoichiometry

Governing Stoichiometry and Metabolic Interferences

The core anammox metabolism follows a well-defined stoichiometry, in which ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) and nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») are converted to dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) under anaerobic conditions. The classic stoichiometric relationship is described by the following equation [15]: NH₄⺠+ 1.32NOâ‚‚â» + 0.066HCO₃⻠+ 0.13H⺠→ 1.02Nâ‚‚ + 0.26NO₃⻠+ 0.066CHâ‚‚Oâ‚€.â‚…Nâ‚€.â‚â‚… + 2.03Hâ‚‚O

This equation reveals two critical stoichiometric ratios for monitoring process performance: the ΔNOâ‚‚â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N consumption ratio (theoretical: ~1.32) and the ΔNO₃â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N production ratio (theoretical: ~0.26). Empirical studies at 30°C have confirmed values close to these theoretical expectations, with reported consumption and production ratios of 1.21 ± 0.11 and 0.25 ± 0.06, respectively [16]. Deviations from these ratios often signal the presence of interfering metabolic processes or suboptimal environmental conditions.

The presence of organic carbon represents a significant environmental filter that shapes microbial community structure by favoring competing heterotrophic denitrifying bacteria (DB). These bacteria compete with AnAOB for the essential electron acceptor, nitrite. The intensity of this competition is largely governed by the chemical oxygen demand (COD) and the carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio of the influent [17]. While a C/N ratio of 0.5 can support synergistic nitrogen removal in integrated systems, a ratio exceeding 2.0 in mainstream wastewater typically triggers intense competition, leading to the suppression of AnAOB and a marked decline in nitrogen removal efficiency [17]. This competitive exclusion represents a clear case of substrate-mediated environmental filtering.

Table 1: Substrate Inhibition Thresholds and Stoichiometric Ratios in Anammox Systems

| Parameter | Theoretical Value | Experimental Value | Inhibition Threshold | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔNOâ‚‚â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N Consumption | 1.32 | 1.21 ± 0.11 [16] | - | Key indicator of anammox activity |

| ΔNO₃â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N Production | 0.26 | 0.25 ± 0.06 [16] | - | Confirms stoichiometric conversion |

| Optimal C/N Ratio | 0.5 [17] | 0.5 [17] | >2.0 (mainstream) [17] | Promotes synergy with denitrifiers |

| NHâ‚„âº-N Influent Concentration (Low-Strength) | - | ~17 mg/L [16] | - | Mimics municipal wastewater partial nitritation effluent |

| NOâ‚‚â»-N Influent Concentration (Low-Strength) | - | ~21 mg/L [16] | - | Must be maintained for stable operation |

Experimental Protocol: Substrate Inhibition and Stoichiometry Assay

Objective: To determine the impact of varying C/N ratios and substrate concentrations on anammox activity and process stoichiometry.

Materials:

- Lab-scale bioreactor (e.g., Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) or Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB))

- Synthetic wastewater feed system

- Anammox biomass (granular or suspended)

- Peristaltic pumps for influent/effluent

- Analytical instruments: Spectrophotometer/Flow Injection Analyzer for NHâ‚„âº-N, NOâ‚‚â»-N, NO₃â»-N; COD reactor

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: Operate a lab-scale UASB reactor with an effective volume of 8 L, inoculated with anammox sludge (e.g., dominated by Candidatus Kuenenia). Maintain temperature at 30±1°C and pH at 7.5-8.0 using a buffer [16].

- Baseline Operation: Establish baseline performance with a synthetic wastewater containing NHâ‚„âº-N (60-700 mg/L) and NOâ‚‚â»-N (80-920 mg/L), and no external organic carbon [18]. Measure the steady-state influent and effluent nitrogen species to confirm the stoichiometric ratios are close to theoretical values.

- C/N Ratio Variation: Introduce sodium acetate or another organic carbon source to the synthetic feed to create a series of C/N ratios (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0). Maintain nitrogen concentrations constant.

- Monitoring and Analysis: For each C/N condition, after reaching steady-state (typically >3 hydraulic retention times), monitor daily:

- Influent & Effluent NHâ‚„âº-N, NOâ‚‚â»-N, NO₃â»-N

- Effluent COD

- Nitrogen Removal Rate (NRR) and Nitrogen Removal Efficiency (NRE)

- Data Processing: Calculate the observed ΔNOâ‚‚â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N and ΔNO₃â»-N/ΔNHâ‚„âº-N ratios. Plot NRE and specific anammox activity against the C/N ratio to identify the inhibition threshold [17].

Diagram 1: Substrate-driven community assembly logic. C/N ratio acts as a key environmental filter, determining the microbial community structure and resulting nitrogen removal performance. PD-DB: Partial Denitrifying Bacteria.

Temperature as a Critical Environmental Filter

Temperature-Dependent Activity and Community Adaptation

Temperature exerts a profound selective pressure on anammox communities, directly influencing metabolic rates and shaping microbial consortia through deterministic selection. AnAOB exhibit a characteristic temperature optimum, typically between 30°C and 40°C [16]. However, their activity is measurable across a much broader range, from below 10°C to over 40°C.

Quantitative data reveals the significant impact of temperature shifts. A pilot-scale study demonstrated that as temperatures decreased from >20°C to <15°C, the contribution of the anammox pathway to total nitrogen removal plummeted from 88.4% to just 8.2%. Concurrently, the system shifted to a denitrification-dominated process, with its contribution rising from 10.1% to 90.1% [19]. This represents a clear temperature-mediated ecological filter, selecting for a different functional microbial guild. Furthermore, the Nitrogen Removal Rate (NRR) is severely affected; one UASB study reported a drop in NRR from 5.73 kg N mâ»Â³ dâ»Â¹ at 30°C to 2.78 kg N mâ»Â³ dâ»Â¹ at 16-20°C [16].

This kinetic response is linked to a shift in the dominant anammox species. The abundance of Candidatus Kuenenia, a common reactor-dwelling AnAOB, was observed to be higher at elevated temperatures, giving it a competitive advantage over denitrifying bacteria in this range [19]. At lower temperatures, other microbial groups like Denitratesoma can become enriched, helping to maintain system robustness through denitrification [19].

Table 2: Temperature-Driven Performance and Kinetic Parameters in Anammox Systems

| Temperature Regime | Nitrogen Removal Rate (NRR) | Dominant Nitrogen Removal Pathway | Contribution to Total N Removal | Key Microbial Shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >20°C (High) | 5.73 kg N mâ»Â³ dâ»Â¹[cite] | Anammox-dominated SAD [19] | Anammox: 88.4% [19] | Candidatus Kuenenia enriched (7.13% abundance) [19] |

| 15-20°C (Moderate) | 4.25 kg N mâ»Â³ dâ»Â¹ (avg) [16] | Transitional SAD [19] | Anammox: ~53.9% [19] | Balance between AnAOB and DB |

| <15°C (Low) | 2.78 kg N mâ»Â³ dâ»Â¹ [16] | Denitrification-dominated SAD [19] | Denitrification: 90.1% [19] | Denitratesoma enriched (3.47% abundance) [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Temperature Kinetics and Thresholds

Objective: To quantify the temperature dependency of anammox activity and identify critical temperature thresholds for process stability.

Materials:

- Temperature-controlled bioreactor (e.g., UASB or SBR with water jacket)

- Thermostatic water bath and circulating pump

- Anammox biomass

- Standard analytical equipment for nitrogen species

Methodology:

- Acclimatization: Start the reactor operation at 30°C with a stable nitrogen load. Allow the system to reach steady-state, indicated by consistent NRR and stoichiometric ratios [16].

- Temperature Variation: Implement a stepwise or gradual decrease in operational temperature. For example, from 30°C → 25°C → 20°C → 16°C, allowing sufficient time (e.g., >20 days per step) for the microbial community to acclimate at each new temperature [16].

- Data Collection: At each temperature steady-state, record:

- Influent and Effluent NHâ‚„âº-N, NOâ‚‚â»-N, NO₃â»-N concentrations

- Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) and Nitrogen Loading Rate (NLR)

- Calculate the NRR and NRE

- Kinetic Analysis: Model the temperature dependency of the NRR. The activation energy for the anammox reaction can be estimated using the Arrhenius equation within the mid-temperature range (e.g., 15-35°C).

- Microbial Community Analysis: At the end of each temperature phase, take sludge samples for DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to track shifts in the relative abundance of AnAOB (e.g., Brocadia, Kuenenia) and denitrifying bacteria (e.g., Denitratesoma) [19].

The pH Filter and Process Stability

Optimal Range and Inhibitory Extremes

pH acts as a stringent physiological filter for anammox bacteria, directly impacting enzyme activity and cellular integrity. The generally accepted optimal pH range for the anammox process is between 7.5 and 8.0 [18]. Operating within this window is critical for maintaining the activity of key enzymes like hydrazine hydrolase (Hzs) and hydrazine dehydrogenase (Hdh).

Deviations from this optimal range can lead to severe inhibition. Excessively low pH (<6.5) can cause the conversion of free ammonia (NH₃) to ammonium (NHâ‚„âº), but more critically, it may disrupt the proton motive force across the anammoxosome membrane, impairing energy conservation [15]. Conversely, at high pH (>8.5), the equilibrium shifts to increase the concentration of free ammonia (FA), which is known to be inhibitory to anammox bacteria even at relatively low concentrations (e.g., >10 mg/L) [20].

Novel strategies are emerging to exploit pH as a selective filter. For instance, the cultivation of acid-tolerant ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) like Candidatus Nitrosoglobus in Membrane Aerated Biofilm Reactors (MABRs) has enabled stable partial nitritation at a pH as low as 5.0-5.2. This acidic environment strongly suppresses nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB), creating ideal conditions (i.e., a mix of NH₄⺠and NOâ‚‚â») for a subsequent anammox process in a two-stage system [15].

Experimental Protocol: Determining pH Optimum and Inhibition

Objective: To establish the optimal pH range for anammox activity and quantify inhibition at pH extremes.

Materials:

- Batch reactors (serum bottles or small bioreactors)

- Active anammox biomass

- pH stat system or buffers for precise pH control

- Titrants (e.g., HCl and NaOH solutions)

- Analytical equipment for nitrogen species

Methodology:

- Batch Test Setup: Dispense equal volumes of well-homogenized anammox sludge into multiple batch reactors.

- pH Adjustment: Set each reactor to a target pH across a defined range (e.g., 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0) using mild acids or bases. Maintain pH constant throughout the experiment using a pH stat system or a robust buffer.

- Activity Assay: Spike all bottles with the same initial concentrations of NHâ‚„âº-N and NOâ‚‚â»-N. Place them on a shaker to ensure mixing and maintain anaerobic conditions.

- Sampling: Take liquid samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) over several hours to track the depletion of NHâ‚„âº-N and NOâ‚‚â»-N.

- Kinetic Calculation: Calculate the Specific Anammox Activity (SAA) for each pH condition, expressed as mg N gâ»Â¹ VSS hâ»Â¹, based on the maximum slope of substrate depletion.

- Data Modeling: Plot SAA against pH to identify the optimum pH and the inhibitory thresholds. The data can be fitted to a non-linear model (e.g., a Gaussian curve) to describe the pH-activity relationship.

Diagram 2: Hierarchical impact of environmental filters. The primary drivers (Substrate, Temperature, pH) exert effects at physiological and ecological levels, which converge to determine overall process performance and ultimately lead to a deterministically filtered microbial community.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Anammox Ecological Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Wastewater Base | Provides essential inorganic nutrients (P, Ca, Mg, trace elements) and buffer capacity. | Used in all continuous and batch cultures to maintain microbial growth and stable pH [18]. |

| Ammonium Chloride (NHâ‚„Cl) | Primary ammonium source for anammox metabolism and microbial growth. | Component of synthetic feed to maintain specific NHâ‚„âº-N influent concentration [16]. |

| Sodium Nitrite (NaNOâ‚‚) | Essential electron acceptor for the anammox reaction. | Component of synthetic feed; concentration is carefully controlled to avoid inhibition [16]. |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) | Inorganic carbon source for autotrophic growth and pH buffer. | Added to synthetic wastewater (e.g., 1.25 g/L) to maintain pH in optimal range (7.5-8.0) [18]. |

| Sodium Acetate (or other organic carbon) | Organic carbon source to manipulate C/N ratio and study heterotrophic competition. | Used in substrate inhibition assays to simulate the impact of organic matter in wastewater [17]. |

| Trace Element Solutions | Supplies vital micronutrients (e.g., Fe, Zn, Co, Cu, Mo) for metalloenzymes in anammox metabolism. | Added in small quantities (e.g., 1 mL/L) to synthetic wastewater to prevent nutrient limitation [18]. |

| Plastic Biofilm Media (e.g., Bee-Cell 2000) | Provides high-surface-area attachment site for biofilm formation, enhancing biomass retention. | Used in upflow anaerobic biofilm reactors to support biomass growth and improve process stability [18]. |

| Ansamitocin P-3 | Ansamitocin P-3, MF:C32H43ClN2O9, MW:635.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CCG 203769 | CCG 203769, MF:C8H14N2O2S, MW:202.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Substrate, temperature, and pH function as powerful deterministic filters in the assembly of anammox bacterial communities. Their effects are quantifiable and predictable, governing system performance through defined stoichiometric relationships, kinetic thresholds, and structured microbial interactions. Mastering these environmental drivers is essential for advancing the application of anammox ecology, enabling more reliable reactor operation, accurate ecosystem modeling, and the development of robust nitrogen removal technologies for a sustainable water cycle. Future research should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches with kinetic modeling to unravel the complex regulatory networks that underpin the deterministic selection processes described herein.

In microbial ecology, the assembly and function of bacterial communities are driven by two fundamental types of interactions: competition and cross-feeding. These interactions are particularly consequential in engineered ecosystems such as wastewater treatment systems, where they determine the efficacy of biotechnological processes. The anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process, renowned for its energy-efficient nitrogen removal capabilities, presents an ideal model system for investigating these microbial interactions. Within anammox consortia, complex networks of competition for resources and cross-feeding of metabolites emerge as critical ecological drivers that shape community structure, stability, and function. This technical guide examines the roles of competition and cross-feeding in anammox bacterial community assembly, integrating contemporary research findings and methodological approaches to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and biotechnology professionals.

Ecological Framework of Microbial Interactions

Microbial interactions form a continuum from cooperative cross-feeding to competitive exclusion, with the balance between these forces determined by environmental conditions, niche availability, and species traits. In anammox systems, these interactions manifest at multiple scales, from the molecular level of metabolite exchange to the population level of resource competition.

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Microbial Interactions in Anammox Systems

| Interaction Type | Ecological Definition | Manifestation in Anammox Systems | Impact on Community Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition | Mutual inhibition between populations seeking the same limited resources | Competition for nitrogen substrates (NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â»), space on biofilm carriers, essential micronutrients | Drives niche partitioning and deterministic assembly; promotes functional heterogeneity |

| Cross-Feeding | One population produces metabolites that benefit another population | Exchange of amino acids, vitamins (B6), cofactors (MOCO), and signaling molecules | Enhances metabolic efficiency and community stability; enables division of labor |

| Cooperative Facilitation | Multiple populations collectively perform functions neither can achieve alone | Anammox bacteria coupled with AOB and DNB for complete nitrogen removal | Increases functional redundancy and system resilience to perturbations |

| Exploitative Interactions | One population benefits from metabolites without reciprocal benefit | "Cheater" strains utilizing pyoverdine siderophores without production costs | Can destabilize communities but may be regulated through spatial structuring |

Deterministic versus Stochastic Assembly

The relative importance of competition and cross-feeding in community assembly is reflected in the balance between deterministic and stochastic processes. Recent research on anammox dynamic membrane bioreactors (DMBRs) reveals that membrane biofilm communities assemble primarily through deterministic processes, particularly homogeneous selection driven by environmental filtering [2] [21]. This deterministic assembly is influenced by factors including substrate affinity variations among anammox genera, limited nitrogen substrate availability in biofilms, and relatively weak permeate drag forces during filtration [2].

In contrast, suspended sludge communities in most anammox bioreactors are primarily governed by stochastic processes like random dispersion and ecological drift [2]. This dichotomy highlights how reactor engineering and operational parameters can fundamentally shift the ecological forces shaping microbial communities, with direct implications for nitrogen removal performance.

Cross-Feeding in Anammox Consortia

Cross-feeding represents the cornerstone of metabolic cooperation in anammox communities, enabling complex metabolic networks that enhance functional efficiency and stability.

Metabolic Cross-Feeding Mechanisms

Table 2: Documented Cross-Feeding Relationships in Anammox Systems

| Exchanged Metabolite | Producer Organisms | Recipient Organisms | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitric Oxide (NO) | Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), Denitrifying bacteria (DNB) | Anammox bacteria | Crucial intermediate enabling alternative anammox pathway with reduced NO₃⻠production [22] |

| Vitamin B6 | Symbiotic bacteria in consortia | Anammox bacteria | Serves as highly effective antioxidant, protecting anammox bacteria from high NH₄⺠concentrations and variable dissolved oxygen [23] |

| Molybdopterin Cofactor (MOCO) | Armatimonadetes, Proteobacteria | Anammox bacteria | Essential cofactor for anammox metabolism; influences carbon fixation and acetyl-CoA production [22] |

| Folate | Symbiotic bacteria | Anammox bacteria | Secondary metabolite supporting growth and activity of anammox bacteria [22] |

| Exopolysaccharides | Acidobacteriota-affiliated bacteria | Anammox consortia | Promotes consortium aggregation and biofilm formation [22] |

| Amino Acids | Anammox bacteria | Symbiotic bacteria | Anammox bacteria synthesize costly amino acids for auxotrophic symbionts [23] |

Nitric Oxide as Key Cross-Fed Metabolite

The cross-feeding of nitric oxide (NO) represents a particularly sophisticated interaction within anammox consortia. Meta-omics analyses reveal that NO produced by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and denitrifying bacteria (DNB) can be directly utilized by anammox bacteria through an alternative metabolic pathway that condenses NO with NH₄⺠to form N₂ [22]. This pathway bypasses the production of NO₃⻠as a byproduct, potentially increasing the nitrogen removal efficiency of the process.

Batch tests with selective inhibitors have confirmed that approximately 91.3% of nitrogen removal can be attributed to anammox activity supported by this NO cross-feeding mechanism, despite anammox bacteria comprising only 14.4% of the community [22]. This demonstrates the profound functional impact that cross-feeding interactions can have on ecosystem processes.

Figure 1: Nitric Oxide (NO) Cross-Feeding Pathway in Anammox Consortia

Dynamic Regulation of Cross-Feeding Under Stress

Cross-feeding relationships are not static but respond dynamically to environmental conditions. Research on full-scale anammox reactors treating sludge digester liquor revealed that under high NH₄⺠concentrations (1785.46 ± 228.5 mg/L), anammox bacteria adjusted their cooperative strategies to reduce metabolic costs [23]. Specifically, anammox bacteria reduced their supply of amino acids to symbiotic partners while increasing uptake of vitamin B6, which served as a critical antioxidant for stress resistance.

This metabolic reallocation demonstrates how microbial communities dynamically optimize resource investment under stressful conditions, prioritizing essential survival functions over cooperative exchanges that carry high metabolic burdens [23].

Competition and Niche Differentiation

While cross-feeding represents cooperative interactions, competition exerts equally powerful selective pressures that shape anammox community assembly and function.

Competition for Substrates and Spatial Niches

In anammox dynamic membrane bioreactors (DMBRs), competition for limited nitrogen substrates (NH₄⺠and NOâ‚‚â») in membrane biofilms creates strong selective pressures that drive deterministic community assembly [2] [21]. Different anammox bacterial genera exhibit varying substrate affinities, leading to niche differentiation and spatial segregation:

- Candidatus Kuenenia: Selectively enriched in membrane biofilms (8.5% abundance) due to high substrate affinity under limited conditions [21]

- Candidatus Brocadia and Jettenia: Occupy distinct niches in suspended sludge versus biofilm environments [2]

This niche differentiation illustrates how competition for resources promotes spatial organization and functional specialization within anammox communities.

Competition Mediated by Secondary Metabolites

Iron competition represents another key competitive interaction mediated through siderophore production and utilization. Research on pseudomonads has revealed complex "lock-key" systems where specific pyoverdine siderophores (keys) match with corresponding receptor proteins (locks), creating intricate interaction networks [24].

These iron competition networks demonstrate distinctive topological properties across habitats and lifestyles:

- Pathogenic strains: Form simpler, more specialized networks dominated by specific lock-key groups

- Environmental strains: Develop complex, interconnected networks with numerous "deceiver" receptors that can utilize siderophores produced by other strains [24]

This habitat-specific network architecture demonstrates how ecological context shapes the evolution of competitive strategies.

Research Methodologies for Investigating Microbial Interactions

Experimental Protocols for Interaction Analysis

Pairwise Interaction Screening Protocol

A standardized method for quantifying microbial interactions involves comparing growth yields in mono-culture versus co-culture systems [25]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Test bacterial strains (e.g., WR4 Flavobacterium johnsoniae, WR21 Chryseobacterium daecheongense)

- Liquid and solid NA media

- 48-well culture plates

- Incubation shaker maintaining 30°C

- Colony counting equipment

Procedure:

- Inoculate single strains separately in NA liquid medium, incubate at 30°C for 12 hours

- Adjust bacterial suspensions to approximately 10ⷠcells/mL (OD₆₀₀ ~0.1)

- For mono-cultures: Transfer 7 μL of single-strain suspension to 693 μL fresh NA medium in 48-well plate

- For co-cultures: Mix equal volumes of two strain suspensions, then transfer 7 μL mixture to 693 μL fresh NA medium

- Incubate plates at 30°C with shaking at 170 rpm for 48 hours

- Serially dilute cultures and plate on solid NA medium for colony counting

- Calculate interaction types based on biomass comparisons:

[ \text{Interaction Type} = \begin{cases} \text{Facilitation} & \text{if } MPi + MPj < CP{i+j} \ \text{Neutral} & \text{if } MPi + MPj = CP{i+j} \ \text{Competition} & \text{if } MPi + MPj > CP_{i+j} \end{cases} ]

Where (MPi) and (MPj) represent mono-culture biomass, and (CP_{i+j}) represents total co-culture biomass [25].

Community Interaction Strength Quantification

For multi-strain communities, the average interaction strength can be quantified using absolute quantitative PCR with strain-specific primers:

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial DNA extraction kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Bacterial DNA Kit)

- Strain-specific 16S rRNA primers

- SYBR Premix Ex Taq for qPCR

- Quantitative PCR instrument

- NanoDrop spectrophotometer for DNA quantification

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from mono-cultures and multi-strain co-cultures after 48 hours incubation

- Design strain-specific primers by aligning full-length 16S rRNA sequences and identifying variable regions

- Validate primer specificity using PCR with all test strains as templates

- Generate standard curves for each strain using known cell concentrations

- Perform quantitative PCR on DNA from co-cultures using each strain-specific primer set

- Calculate observed interaction strength (OIF) for n-strain communities:

[ \text{OIF} = \frac{\sum \log{10}(\frac{CPi}{MP_i})}{n} ]

Where (CPi) represents strain i biomass in co-culture, and (MPi) represents strain i biomass in mono-culture [25].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Microbial Interaction Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Microbial Interactions

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Valent Iron (ZVI) | Nanopowder, 65-75 nm particle size, >99.5% Fe | Enhancing anammox activity at low temperatures (10-30°C) [26] | Stimulates specific anammox activity; modulates oxidative stress; promotes key genera (Ca. Brocadia) |

| Selective Inhibitors | Specific metabolic pathway inhibitors | Differentiating contributions of AOB, DNB, and anammox bacteria [22] | Enables dissection of individual functional group contributions in complex consortia |

| SAG Bioink | Alginate-Gelatin composite with microbial suspension | 3D bioprinting of stable denitrifier niches [27] | Creates controlled microenvironments with optimized porosity, mechanical stability, and metabolic activity |

| Strain-Specific Primers | 16S rRNA variable region targets | Absolute quantification of strain abundances in co-cultures [25] | Enables precise tracking of population dynamics in complex communities |

| Metabolic Analytes | Vitamin B6, amino acids, NO detection assays | Tracking cross-fed metabolites in anammox consortia [23] | Quantifies metabolic exchange rates and pathways |

| Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Extraction Kits | Chemical extraction and quantification | Analyzing biofilm matrix components in anammox granules [2] | Characterizes structural foundation of microbial aggregates |

| Elabela(19-32) | Elabela(19-32), MF:C75H119N25O17S2, MW:1707.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CW-069 | CW-069, MF:C23H21IN2O3, MW:500.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Technological Applications and Engineering Strategies

Biofilm Reactor Engineering

The manipulation of microbial interactions enables significant advances in wastewater treatment engineering. In anammox dynamic membrane bioreactors (DMBRs), the deterministic assembly of membrane biofilm communities can be harnessed to enhance nitrogen removal performance [2]. Engineering strategies include:

- Substrate gradient control: Creating limited nitrogen substrate conditions in membrane biofilms to selectively enrich high-affinity anammox bacteria like Candidatus Kuenenia

- Permeate drag force optimization: Regulating filtration forces to promote preferential colonization of functional microbes from suspended sludge to membrane biofilm

- Niche differentiation promotion: Utilizing distinct inoculated anammox sludges to create spatially segregated functional zones

These engineered communities demonstrate significantly improved nitrogen removal efficiency, with membrane biofilms contributing 5.2-7.2% of the total nitrogen removal load despite representing only 8.5% of the community abundance [21].

3D Bioprinting for Stable Ecological Niches

Emerging technologies like 3D bioprinting enable unprecedented control over microbial microenvironment design. Recent research demonstrates the construction of stable niches for denitrifiers using 3D bioprinting with optimized bioink composed of alginate, gelatin, and bacterial suspensions [27]. This approach yields:

- Enhanced functional performance: 3D-bioprinted denitrifying materials achieve >95% total nitrogen and COD removal, matching the performance of 10-fold higher concentrations of free cells

- Improved ecological stability: Functional bacteria relative abundance increases by nearly 60% compared to free-cell systems

- Superior mechanical properties: Printed structures demonstrate Young's modulus of 0.1075 MPa and fracture energy of 611.69 J/m², enabling resilience in complex hydraulic environments

- Optimal mass transfer: Controlled pore structures (20×20×5 mm with 4 mm spacing) enhance substrate diffusion and metabolic product removal

This biofabrication approach represents a paradigm shift in environmental biotechnology, enabling precise ecological niche construction for enhanced process stability and functionality [27].

Microbial interactions through competition and cross-feeding constitute fundamental ecological drivers that shape the assembly, stability, and function of anammox bacterial communities. The intricate balance between these opposing forces determines community structure and metabolic efficiency in engineered ecosystems. Contemporary research reveals that these interactions are not fixed but dynamically responsive to environmental conditions, with communities adjusting cooperation strategies under stress and competition driving niche differentiation.

Advanced methodological approaches, including pairwise interaction screening, molecular quantification of population dynamics, and engineered niche construction through 3D bioprinting, provide powerful tools for investigating and harnessing these interactions. As our understanding of these complex ecological relationships deepens, novel opportunities emerge for optimizing biotechnological processes through targeted management of microbial community interactions. Future research directions should focus on real-time monitoring of interaction dynamics, evolutionary trajectories of cooperative systems, and integration of interaction network data into predictive models for enhanced ecosystem engineering.

The ecological drivers governing the assembly of anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) bacterial communities are a central focus in modern wastewater treatment research. A critical aspect of this ecological understanding is the pronounced spatial differentiation between two key microhabitats: suspended sludge and membrane biofilms. In engineered anammox systems, such as membrane bioreactors (MBRs) and dynamic membrane bioreactors (DMBRs), these distinct niches support microbial communities that differ fundamentally in their assembly mechanisms, composition, and function [2] [28]. Understanding the deterministic and stochastic processes that shape these communities is essential for optimizing nitrogen removal performance and advancing the application of anammox technology. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth technical guide on the ecological drivers of anammox bacterial community assembly across different spatial niches, framing these findings within the broader context of microbial ecology.

Core Concepts and Ecological Framework

Defining the Niches: Suspended Sludge vs. Membrane Biofilms

In anammox bioreactors, suspended sludge and membrane biofilms represent distinct microhabitats with unique physicochemical properties. Suspended sludge consists of microbial aggregates freely moving in the liquid phase, while membrane biofilms are surface-attached communities that develop on filtration membranes [2] [28]. These differences in physical structure create variations in substrate availability, mass transfer limitations, and shear forces, ultimately driving divergent ecological assembly processes.

From an ecological perspective, community assembly is governed by the balance between deterministic and stochastic processes. Deterministic processes include environmental selection, where abiotic factors like substrate concentration or dissolved oxygen shape the community, and biotic interactions such as competition or cooperation. Stochastic processes encompass random birth-death events (ecological drift), dispersal limitations, and random colonization [2] [29]. The relative influence of these processes varies significantly between suspended and biofilm habitats.

Anammox Process Biochemistry and Key Microorganisms

Anammox bacteria are chemolithoautotrophic organisms that belong to the phylum Planctomycetes. They anaerobically oxidize ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) using nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») as an electron acceptor to produce dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) [15]. The metabolic pathway occurs within a specialized organelle called the anammoxosome and involves the intermediate production of hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„), a highly reactive compound [15]. The overall stoichiometry of the reaction is: NH₄⺠+ 1.32 NOâ‚‚â» + 0.066 HCO₃⻠+ 0.13 H⺠→ 1.02 Nâ‚‚ + 0.26 NO₃⻠+ 0.066 CHâ‚‚Oâ‚€.â‚…Nâ‚€.â‚â‚… + 2.03 Hâ‚‚O [15]

Several anammox genera have been identified, each with distinct ecological preferences and substrate affinities. The most common genera include:

- Candidatus Brocadia: Frequently dominant in suspended sludge systems [28]

- Candidatus Kuenenia: Often preferentially enriched in membrane biofilms [2] [21]

- Candidatus Jettenia: Tolerant of low nitrogen loading rates [30]

- Candidatus Scalindua: Dominant in marine and saline environments [29] [11]

Table 1: Key Anammox Bacterial Genera and Their Characteristics

| Genus | Preferred Habitat | Key Characteristics | Relative Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca. Brocadia | Suspended sludge | Common in wastewater treatment plants | Moderate |

| Ca. Kuenenia | Membrane biofilms | High substrate affinity; biofilm-adapted | Moderate |

| Ca. Jettenia | Low-load systems | Tolerates low nitrogen loading | Slow |

| Ca. Scalindua | Marine/saline environments | Salt-tolerant; dominant in marine sediments | Variable |

Quantitative Comparison of Community Assembly

Performance and Community Structure Metrics

Recent comparative studies have revealed systematic differences between suspended sludge and membrane biofilm communities in anammox systems. The spatial differentiation of anammox bacteria significantly influences nitrogen transformation pathways and overall reactor performance [2] [31].

Table 2: Comparative Performance and Community Metrics in Anammox DMBRs

| Parameter | Suspended Sludge | Membrane Biofilm | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anammox abundance | Variable (inoculum-dependent) | Up to 8.5% selective enrichment of Ca. Kuenenia | 16S rRNA gene sequencing [21] |

| NH₄⺠removal contribution | ~70-80% of total removal | 5.2-7.2% of nitrogen removal load | Mass balance calculation [2] |

| Community assembly process | Primarily stochastic (ecological drift) | Primarily deterministic (homogeneous selection) | Neutral community model; null model analysis [2] |

| Dominant anammox genus | Ca. Brocadia or Ca. Jettenia | Ca. Kuenenia (preferentially enriched) | High-throughput sequencing [2] [28] |

| Influence of permeate drag force | Minimal direct influence | Significant influence on community structure | Controlled filtration experiments [2] |

Ecological Assembly Mechanisms

The assembly processes governing suspended sludge and membrane biofilm communities follow fundamentally different trajectories. In suspended sludge, stochastic processes predominantly shape the community, with ecological drift explaining a substantial portion of community variation [2]. This results in more unpredictable community composition and greater susceptibility to random fluctuations in population dynamics.

In contrast, membrane biofilm communities are primarily assembled through deterministic processes, particularly homogeneous selection [2] [21]. This process accounts for approximately 9.67-9.82% of the variance in membrane biofilm communities, significantly higher than in suspended sludge [21]. The deterministic assembly is driven by consistent environmental filters, including limited substrate availability (NH₄⺠and NOâ‚‚â») due to mass transfer resistance within the biofilm matrix, and the relatively weak permeate drag force during DMBR filtration that enables selective colonization [2].

Research Methods and Experimental Approaches

Core Methodologies for Studying Community Assembly

Investigating spatial differentiation in anammox systems requires integrated experimental and analytical approaches. The following workflow outlines key methodologies used in this field:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Reactor Operation and Sampling

Lab-scale anammox DMBRs are typically operated for extended periods (e.g., 360 days) to observe community succession [2]. Systems are inoculated with different anammox sludges dominated by specific genera (e.g., Candidatus Kuenenia or Candidatus Jettenia) to track population dynamics. The bioreactors employ submerged flat-sheet membrane modules with a total filtration area of approximately 0.02 m² and operate with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 24-48 hours [2]. Sampling involves collecting both suspended sludge and membrane biofilm samples at regular intervals for comparative analysis.

Nitrogen Removal Performance Assessment

Regular monitoring of nitrogen compounds (NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â», NO₃â») in influent and effluent streams is conducted using standard methods [2]. Total nitrogen removal efficiency (TNRE) is calculated as: TNRE (%) = [(Influent TN - Effluent TN) / Influent TN] × 100. In DMBR systems, the specific contribution of membrane biofilms to nitrogen removal is quantified by comparing removal rates before and after biofilm development, or by selectively inhibiting specific pathways [2].

Molecular Biological Analysis

DNA Extraction and Amplification: Total genomic DNA is extracted from samples using commercial kits (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for soil) [11]. The 16S rRNA gene of anammox bacteria is amplified using specific primer sets such as Brod541F and Amx820R [11].

High-Throughput Sequencing: Amplified genes are sequenced using Illumina platforms. Processing of raw sequences involves quality filtering, chimera removal, and clustering into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity threshold [30] [11].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Absolute abundances of anammox bacteria and functional genes are quantified using SYBR Green-based qPCR assays with genus-specific primers [28].

Community Assembly Analysis

Null Model Testing: The relative importance of deterministic vs. stochastic processes is quantified using null model approaches [2]. The deviation of observed community similarity from that expected under stochastic assembly is measured using β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) [29]. |βNTI| > 2 indicates predominantly deterministic assembly, while |βNTI| < 2 suggests stochastic dominance [2].

Co-occurrence Network Analysis: Microbial interactions are investigated through correlation-based network construction using SparCC algorithm [30]. Network topology parameters (modularity, connectivity, centrality) identify keystone species and potential interactions between anammox and denitrifying bacteria [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Anammox Community Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function/Principle | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastDNA SPIN Kit | DNA extraction | Efficient lysis and purification of microbial DNA from complex matrices | MP Biomedical, suitable for soil and sludge samples [11] |

| Brod541F/Amx820R primers | Anammox detection | Specific amplification of anammox bacterial 16S rRNA gene | Target ~279 bp region; annealing temperature ~56°C [11] |

| PBS Buffer | Sample preparation | Washing sludge samples to remove residual substrates | 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 [28] |

| ¹âµN-labeled substrates | Isotopic tracing | Quantifying anammox contribution to Nâ‚‚ production | ¹âµNH₄⺠as tracer; analysis by mass spectrometry [28] |

| Polyurethane sponge fillers | Biofilm carriers | Providing surface for biofilm attachment and growth | Used in bioreactors to enhance microbial attachment [30] |

| Trace element solution | Microbial growth | Supplying essential micronutrients for anammox metabolism | Contains EDTA, Fe²âº, Zn²âº, Cu²âº, etc. [28] |

| FR122047 | FR122047, MF:C23H25N3O3S, MW:423.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PLH1215 | PLH1215, MF:C19H26N4O, MW:326.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Mechanisms Underlying Spatial Differentiation

Environmental Drivers of Niche Partitioning

The spatial differentiation between suspended sludge and membrane biofilms is driven by distinct environmental conditions in each microhabitat. Key factors include:

Substrate Gradients: Membrane biofilms exhibit steeper substrate concentration gradients due to diffusion limitations, creating distinct microenvironments [2]. Candidatus Kuenenia, with its high substrate affinity, is selectively enriched in the substrate-limited biofilm environment [2] [21].

Hydrodynamic Forces: The permeate drag force during filtration creates selective pressure that influences microbial colonization on membranes [2]. Weaker drag forces promote more deterministic assembly by enabling preferential attachment of specific taxa.

Oxygen Gradients: In integrated fixed-film systems, oxygen penetration depth creates aerobic, anoxic, and anaerobic zones within biofilms, allowing coexistence of aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and anaerobic anammox bacteria [32] [28].

Microbial Interactions and Cross-Feeding

Complex microbial interactions contribute to spatial differentiation. Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) have revealed that dominant denitrifiers can provide essential resources for anammox bacteria, including amino acids, cofactors, and vitamins [30]. These cross-feeding relationships are structured spatially, with different interactions occurring in suspended versus biofilm habitats.

Niche differentiation is also influenced by the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Anammox bacteria, particularly Candidatus Brocadia sinica, exhibit highly hydrophobic cell surfaces that promote aggregation and biofilm formation [32]. The composition and molecular structure of EPS vary between suspended and biofilm communities, further reinforcing spatial differentiation [32].

Implications and Future Research Directions

Applications in Wastewater Treatment

Understanding spatial differentiation in anammox systems enables more efficient bioreactor design and operation. The findings directly inform:

Bioreactor Optimization: Knowledge of deterministic assembly in biofilms allows for precise manipulation of membrane biofilm communities to enhance nitrogen removal [2] [21].

Process Stability: The cooperation between anammox and denitrifying bacteria in biofilms increases community stability and functional resilience [30].

Advanced Configurations: Integration of anammox with heterotrophic processes in biofilm systems enables treatment of complex wastewaters while maintaining process efficiency [32].

Knowledge Gaps and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in understanding and exploiting spatial differentiation in anammox systems:

Mechanistic Drivers: Further research is needed to precisely quantify the contribution of specific factors (substrate affinity, attachment mechanisms, microbial interactions) to niche differentiation [2].

Advanced Imaging Techniques: Application of high-resolution techniques like FISH-NanoSIMS could spatially resolve metabolic activities and interactions within biofilms.

Rare Biosphere Dynamics: The functional roles of rare anammox taxa in community assembly and ecosystem functioning require further investigation [29] [11].

Process Control Strategies: Developing real-time monitoring and control strategies that account for spatial differentiation could optimize reactor performance and stability [32].

In conclusion, the spatial differentiation between suspended sludge and membrane biofilms represents a fundamental ecological phenomenon with significant implications for anammox process optimization. The deterministic assembly of specialized anammox communities in membrane biofilms, contrasted with the stochastic assembly in suspended sludge, provides a framework for targeted management of functional microbial communities in wastewater treatment systems.

Engineering Ecosystems: Methodologies for Harnessing and Applying Anammox Assembly

The pursuit of efficient and resilient biological wastewater treatment has catalyzed a paradigm shift from simply evaluating bioreactor performance to fundamentally understanding and engineering the microbial ecosystems within them. Central to this is the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process, a revolutionary microbial reaction that converts ammonium and nitrite directly into nitrogen gas under anoxic conditions, offering significant energy and cost savings over traditional nitrogen removal methods [33]. The core challenge, however, lies in the slow growth rate of anammox bacteria (doubling time >11 days) and their susceptibility to environmental perturbations, making biomass retention and community control paramount [2] [33]. This guide examines three advanced bioreactor configurations—Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs), Dynamic Membrane Bioreactors (DMBRs), and Biofilm Reactors—through the lens of microbial community assembly (MCA), the ecological processes that determine how these complex communities develop, function, and withstand stress [34]. A nuanced understanding of the interplay between deterministic (predictable, selection-based) and stochastic (random, dispersal-based) assembly processes enables researchers to move beyond black-box approaches and strategically design systems for enhanced nitrogen removal [2] [34] [6].

Core Bioreactor Configurations: Mechanisms and Microbial Niches

The physical configuration of a bioreactor defines the microhabitats available to microorganisms, thereby directly influencing the assembly and function of the microbial community.

Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs)

MBRs employ a microfiltration or ultrafiltration membrane (typically with a pore size of 0.1 µm) to achieve complete biomass retention, effectively decoupling the hydraulic retention time (HRT) from the solids retention time (SRT) [2] [33]. This is critical for anammox processes, as it prevents the washout of slow-growing bacteria, allowing for rapid start-up and high biomass concentrations [33]. The primary ecological challenge in MBRs is membrane fouling, a complex process driven by the adsorption of anammox microorganisms, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and soluble microbial products (SMP) onto membrane surfaces [33]. This fouling layer creates a unique microhabitat with potential mass transfer limitations for substrates like ammonium and nitrite. While this can lead to functional stratification, it also increases operational costs and complexity due to the need for membrane cleaning and fouling control strategies, such as optimizing gas sparging or backwashing [33].

Dynamic Membrane Bioreactors (DMBRs)

DMBRs represent an evolution of the MBR concept, utilizing a coarse-pore support material (e.g., nylon mesh) upon which a functional, self-forming "dynamic membrane" or "cake layer" develops [2]. This biofilm layer serves a dual purpose: it acts as the filtration barrier and, crucially, as a highly active site for nitrogen removal. Research shows that anammox bacteria, particularly Candidatus Kuenenia, can be preferentially enriched within this dynamic membrane, contributing significantly to the total nitrogen removal [2]. Ecologically, the assembly of the membrane biofilm community in DMBRs is strongly influenced by deterministic processes. Key factors include: