eDNA Metabarcoding in Agriculture: A Revolutionary Tool for Biodiversity Monitoring and Pest Surveillance

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is a transformative, non-invasive method for assessing agricultural ecological communities.

eDNA Metabarcoding in Agriculture: A Revolutionary Tool for Biodiversity Monitoring and Pest Surveillance

Abstract

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is a transformative, non-invasive method for assessing agricultural ecological communities. This approach detects genetic material shed by organisms into their environment—such as soil, water, and air—enabling comprehensive biodiversity monitoring, invasive species biosurveillance, and pathogen detection. While eDNA metabarcoding offers a sensitive, efficient, and scalable alternative to traditional field surveys, its accuracy can be influenced by factors like pH, temperature, and methodological choices, making it a powerful complement to, rather than a full replacement for, conventional methods. This article explores the foundational principles, methodological optimizations, practical applications, and validation frameworks of eDNA metabarcoding, providing researchers and agricultural professionals with a roadmap for integrating this technology into modern farming systems to enhance food security and ecosystem management.

The Foundation of eDNA: Unlocking the Hidden Biodiversity in Agricultural Ecosystems

Environmental DNA (eDNA) is the genetic material shed by organisms into their surrounding environment through various biological materials such as mucus, feces, urine, gametes, shed skin, and decomposing tissues [1] [2]. This DNA can be extracted from environmental samples including water, soil, sediments, and even air, without the need to directly observe or capture the organisms themselves [2] [3]. In the context of agroecosystems, eDNA technology offers a transformative approach for monitoring biodiversity, tracking pathogens, and assessing ecosystem health with minimal disturbance to crops and local wildlife [4].

The application of eDNA analysis represents a paradigm shift in ecological monitoring, moving from traditional observational methods to molecular-based detection. Since the first seminal manuscript was published in 2008, eDNA tools have seen rapid adoption for their sensitivity, efficiency, and non-invasive nature [3]. For agricultural research, this technology provides unprecedented opportunities to monitor windborne crop pathogens, assess soil microbial communities, and track beneficial insects and pests within farming landscapes [4].

In agricultural environments, eDNA originates from multiple biological processes and can be categorized based on its mechanism of release:

Lysis-Associated eDNA Release: This occurs when cells undergo breakdown due to bacterial endolysins, prophages, virulence factors, or antibiotics. In agroecosystems, this can include pathogen destruction from plant defenses or agricultural treatments. For example, iron-induced activation of prophages can enhance eDNA release from lysed cells, while virulence factors like hemolysins and leukotoxins play central roles in quorum-sensing mechanisms that regulate cell lysis [2].

Lysis-Free eDNA Release: eDNA can be actively secreted through mechanisms involving membrane vesicles, eosinophils, and mast cells. Living cells may also release eDNA in response to pathogen attacks. Notably, plant root tips release eDNA functioning analogously to human neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in defense against pathogens, a particularly relevant mechanism in agricultural contexts [2].

Shedding rates of eDNA vary considerably among species and even among individuals of the same species, influenced by factors such as stress (which can amplify tissue shedding rates by up to 100 times), age, diet, water temperature, and the composition of the surrounding biological community [2].

Distribution Across Agricultural Matrices

eDNA distribution varies significantly across different agricultural environmental matrices, each presenting unique opportunities for monitoring:

Soil eDNA: Soil represents a rich reservoir of eDNA in agricultural systems, with concentrations typically ranging from 0.03 to 200 µg/g [2]. Most eDNA is found in upper soil layers, with concentrations decreasing with depth. Soil-bound eDNA is protected from nuclease destruction, allowing for detection of historical biological signals. Soil composition, organic matter content, pH levels, and microbial activity are crucial factors influencing DNA preservation in agricultural soils [2].

Aquatic eDNA: In agricultural water systems (irrigation channels, farm ponds, and rice paddies), eDNA is distributed throughout the water column and can be transported over considerable distances by water movement. Concentrations in mesotrophic waters range from 2.5 to 46 µg/L, while eutrophic waters contain 11.5 to 72 µg/L [2]. This transport characteristic means detected eDNA may not always indicate current presence at the sampling location [2].

Airborne eDNA: Recent research demonstrates that air, while having the lowest DNA concentration of all environmental media, contains sufficient eDNA for monitoring agriculturally significant species. Airborne eDNA enables tracking of pathogen abundance changes over time, often correlating with weather variables, providing critical early warning systems for disease outbreaks in monoculture systems [4].

Table 1: eDNA Concentration Ranges Across Agricultural Environmental Matrices

| Environmental Matrix | Typical eDNA Concentration Range | Primary Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Soil | 0.03 - 200 µg/g | Soil composition, organic matter, pH, microbial activity, depth [2] |

| Freshwater (Mesotrophic) | 2.5 - 46 µg/L | Trophic state, season, temperature, flow rates [2] |

| Freshwater (Eutrophic) | 11.5 - 72 µg/L | Nutrient loading, biological activity, season [2] |

| Sediments | 0.5 - 96.8 µg/g | Particle adsorption, depth, organic content [2] |

| Air | Lowest concentration of all media | Air currents, precipitation, relative humidity [4] |

Quantitative Analysis of eDNA in Ecosystems

Understanding the distribution patterns and concentrations of eDNA across different ecosystem types provides valuable context for agricultural applications. The following table summarizes key quantitative data available from eDNA research across various environments.

Table 2: Quantitative Distribution of eDNA Across Ecosystem Types

| Ecosystem Type | Specific Environment | eDNA Concentration | Key Factors Affecting Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Ecosystems | Water Column (Mesotrophic) | 2.5 - 46 µg/L [2] | Currents, temperature, trophic state, season [2] |

| Water Column (Eutrophic) | 11.5 - 72 µg/L [2] | Nutrient loading, biological activity [2] | |

| Sediments (Marine) | 0.30 - 0.45 Gt (total in deep-sea sediments) [2] | Particle adsorption, depth, preservation conditions [2] | |

| Sediments (Haihe River) | 96.8 ± 19.8 µg/g [2] | Organic content, deposition rates [2] | |

| Sediments (Lake Towuti) | 0.5 - 0.6 µg/g (surface layer) [2] | Depth, mineral composition [2] | |

| Terrestrial Ecosystems | Soil | 0.03 - 200 µg/g [2] | Soil type, depth, organic matter, pH, microbial activity [2] |

Experimental Protocols for eDNA Analysis in Agricultural Research

Field Sampling Protocol

Proper field sampling is critical for obtaining reliable eDNA data. The following protocol adapts established methodologies for agricultural contexts [1] [5]:

Water Sampling:

- Collect water samples using sterile containers or specialized sampling equipment like Niskin bottles, avoiding sediment disturbance.

- Filter water through cellulose nitrate membrane filters (typically 0.22 µm pore size) using sterile syringes or peristaltic pumps.

- Record essential metadata: GPS coordinates, depth, salinity, temperature, and habitat characteristics.

- Process filters immediately or preserve in buffer solutions for transport [1].

Soil Sampling:

- Collect soil cores using sterile corers, documenting depth and horizon information.

- For spatial studies, implement stratified random sampling with multiple replicates to account for heterogeneity.

- Store samples in sterile containers and freeze immediately at -20°C or preserve in DNA stabilization buffers [2].

Air Sampling:

- Utilize active air sampling systems that draw known air volumes through DNA collection filters.

- Consider meteorological conditions during sampling, as wind speed, direction, and humidity affect airborne eDNA concentration.

- Process filters following similar protocols to water sampling [4].

Laboratory Processing and Analysis

The laboratory workflow for eDNA analysis involves multiple critical steps:

DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits specifically designed for environmental samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater Sterivex Kit). Include extraction blanks as negative controls in each batch to monitor contamination [5].

PCR Amplification and Metabarcoding:

- Design or select primer pairs targeting taxonomically informative gene regions (e.g., COI for animals, ITS for fungi, 16S for bacteria).

- For genetic diversity studies, design primers to amplify specific fragments that discriminate between haplotypes or lineages [5].

- Perform PCR amplification with appropriate controls (negative controls to detect contamination, positive controls to verify reaction efficiency).

- Utilize next-generation sequencing platforms for metabarcoding applications to characterize entire communities [6].

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal.

- Cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Assign taxonomy using reference databases (e.g., BOLD, SILVA, UNITE).

- For population-level studies, identify haplotypes by comparing to known sequences [5] [7].

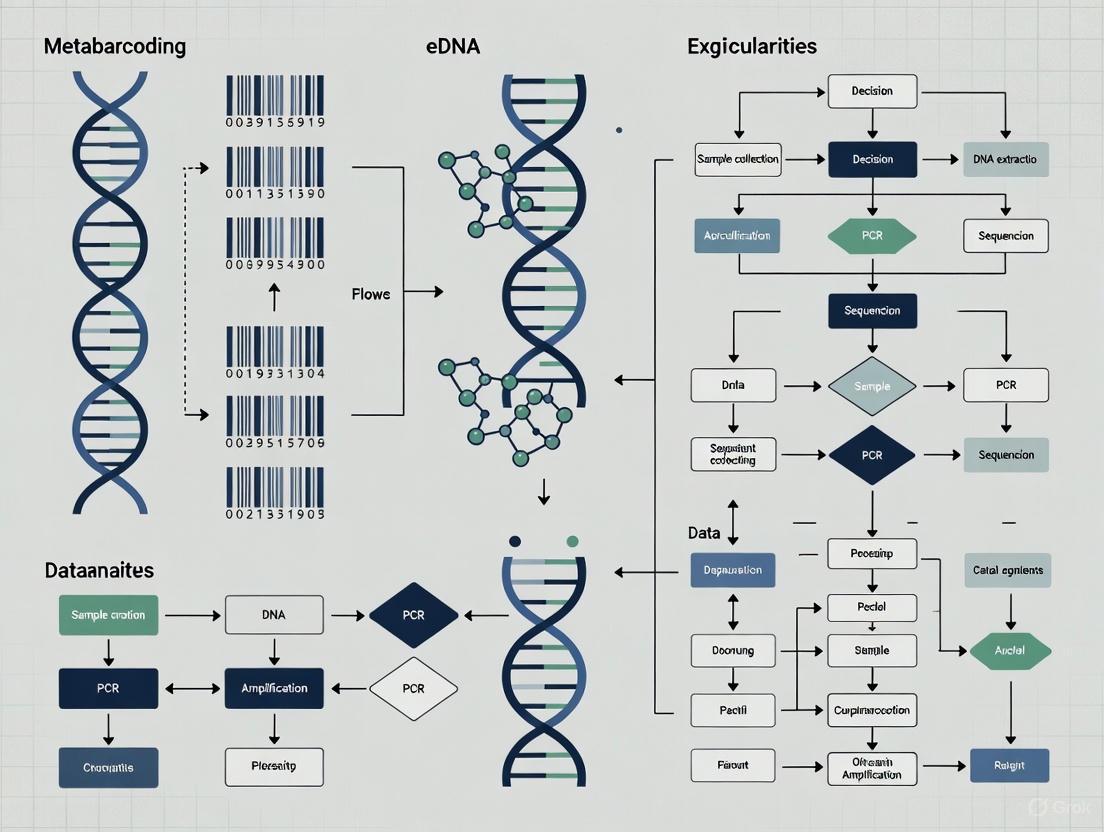

Diagram 1: Complete eDNA analysis workflow from field sampling to data interpretation, highlighting the three major phases of eDNA studies in agricultural research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful eDNA research requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for environmental samples. The following table details essential components of the eDNA research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Studies in Agroecosystems

| Category | Specific Product/Type | Function in eDNA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Equipment | Niskin Bottles | Collect water samples at specific depths without contamination [1] |

| Sterivex-GP Filter Units (0.22 µm) | Capture eDNA particles from water samples during filtration [5] | |

| Sterile Plastic Canisters | Collect and transport water samples while minimizing contamination [5] | |

| Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerWater Sterivex Kit | Extract DNA from water filters with minimal inhibitor co-extraction [5] |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | Optimized for difficult-to-lyse environmental samples like soil [2] | |

| PCR Reagents | Taxon-Specific Primers | Amplify target DNA fragments for species detection [5] |

| Universal Primers (e.g., COI, 16S, ITS) | Amplify DNA from multiple taxa for community metabarcoding [6] | |

| PCR Controls (Positive/Negative) | Monitor contamination and reaction efficiency [5] | |

| Preservation Solutions | DNA/RNA Shield Buffer | Preserve eDNA integrity during sample transport and storage [1] |

| Ethanol or ATL Buffer | Stabilize samples until DNA extraction can be performed [1] | |

| AR-M 1000390 hydrochloride | AR-M 1000390 hydrochloride, MF:C23H29ClN2O, MW:384.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (25RS)-26-Hydroxycholesterol-d4 | (25RS)-26-Hydroxycholesterol-d4, CAS:956029-28-0, MF:C27H46O, MW:390.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Agricultural Ecological Monitoring

eDNA technology offers diverse applications for monitoring agricultural ecological communities:

Pathogen and Pest Surveillance: Airborne eDNA enables tracking of crop pathogen abundance, such as Puccinia striiformis (wheat stripe rust), with changing weather conditions, allowing for early intervention [4]. Soil eDNA can detect root pathogens and nematode communities before visible crop damage occurs.

Biodiversity Assessment: eDNA metabarcoding provides comprehensive biodiversity inventories of agricultural landscapes, detecting everything from soil microbes to beneficial insects and vertebrates [6]. Studies demonstrate eDNA can detect approximately 1.3 times more species than traditional survey methods [6].

Invasive Species Detection: Early detection of invasive species is crucial for agricultural protection. eDNA monitoring of ship ballast water has successfully identified invasive mussel species, demonstrating applications for detecting agricultural invaders in irrigation systems [6].

Genetic Diversity Monitoring: Beyond species presence, eDNA can monitor within-species genetic diversity. Protocols have been validated for detecting mitochondrial DNA haplotypes of amphibian species from water samples, with applications for tracking genetic diversity of non-target species in agricultural ecosystems [5].

Ecosystem Health Assessment: By characterizing biological community changes, eDNA serves as a sensitive indicator of environmental stress from agricultural practices, helping to assess the impact of management strategies and restoration efforts [3] [6].

Diagram 2: Key agricultural applications of eDNA monitoring technology, showing the breadth of uses from pathogen surveillance to ecosystem health assessment in agroecosystems.

Considerations and Limitations for Agricultural Applications

While eDNA technology offers powerful capabilities for monitoring agricultural ecosystems, researchers must consider several important limitations:

Spatial and Temporal Uncertainty: eDNA can be transported from its origin, making precise localization challenging, particularly in aquatic environments with active flow [2]. Temporal detection windows vary significantly, with eDNA persisting from days to several weeks depending on environmental conditions [2].

Detection Sensitivity Issues: False negatives may occur when target organisms are present but eDNA concentration falls below detection thresholds. False positives can result from contamination or detection of eDNA transported from other locations [8] [9].

Quantification Challenges: While eDNA concentration often correlates with biomass, the relationship is not consistently predictable across species and environments due to varying shedding rates and degradation dynamics [2] [9].

Reference Database Limitations: Accurate taxonomic assignment depends on comprehensive reference databases, which remain incomplete for many agricultural taxa, particularly microbes and invertebrates [3] [9].

Standardization Needs: Methodological standardization is still evolving, with current protocols often specific to individual laboratories or projects, complicating cross-study comparisons [3] [9].

These limitations highlight the importance of complementary approaches, where eDNA methods enhance rather than entirely replace traditional monitoring techniques in agricultural research [2] [8].

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has emerged as a transformative tool for monitoring biodiversity in agricultural landscapes, enabling researchers to characterize ecological communities through genetic material recovered from various substrates. In agricultural settings, eDNA metabarcoding provides a non-invasive, high-throughput method for simultaneously detecting a wide range of organisms, including crops, pests, pathogens, beneficial insects, and soil microbiota [2] [10]. The selection of appropriate substrates is paramount for generating comprehensive biodiversity data, as different substrates capture distinct components of agricultural ecosystems. Soil, water, plant surfaces, and air each contain unique eDNA signatures that reflect the complex interactions within agroecosystems, from below-ground microbial processes to airborne pest dispersal patterns.

Agricultural monitoring presents unique challenges for eDNA applications, including the presence of PCR inhibitors in soil, rapid DNA degradation in sun-exposed environments, and the need for precise spatial attribution in mixed-crop landscapes. Despite these challenges, eDNA technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to advance sustainable agriculture by providing detailed insights into pest population dynamics, soil health indicators, and the efficacy of management interventions [10] [11]. This review synthesizes current methodologies and applications of eDNA substrate analysis in agricultural contexts, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these approaches in farm-scale monitoring programs.

Comparative Analysis of eDNA Substrates

Substrate Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of primary eDNA substrates in agricultural monitoring

| Substrate | Target Biota | Sampling Density | DNA Yield | Persistence | Key Applications in Agriculture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Soil microbes, microfauna, plant roots, decaying organisms | 5-10 samples/ha | 0.03-200 µg/g [2] | Weeks to months | Soil health assessment, microbial community dynamics, pathogen detection |

| Plant Surfaces (Phyllosphere) | Pathogens, pests, pollinators, epiphytic microbes | 10-30 leaves/field | Variable; requires optimized extraction | Hours to days | Pest monitoring, disease surveillance, beneficial insect detection |

| Air | Airborne spores, pollen, insects, vertebrate DNA | 3-5 samplers/field | Low concentration; requires filtration | Hours | Pollinator tracking, pathogen dispersal, pest migration patterns |

| Water | Aquatic organisms, runoff-associated DNA, irrigation sources | 1-2 samples/water source | 2.5-88 µg/L [2] | Days to weeks | Irrigation pathogen monitoring, watershed-scale biodiversity |

| Spider Webs | Airborne insects, vertebrates, pollen | 3-5 webs/field | Comparable to leaf swabs [12] | Weeks (protected) | Passive pest monitoring, vertebrate presence, biodiversity indices |

Biodiversity Detection Efficiency Across Substrates

Table 2: Biodiversity detection metrics for different eDNA substrates in agricultural landscapes

| Substrate | Taxonomic Richness | Microbial Diversity (Shannon Index) | Pest Detection Rate | Sample Processing Time | Cost per Sample (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | High (150+ OTUs) [11] | 3.87 (organic farms) [10] | Moderate | 2-3 days | $25-40 |

| Plant Surfaces | Moderate (80-140 OTUs) [11] | 2.1-3.2 | High | 1-2 days | $20-35 |

| Air | Variable (70-130 OTUs) [11] | 2.8-3.5 | Moderate-High | 1-2 days | $30-50 |

| Spider Webs | 63 taxa (forest study) [12] | Not assessed | High for flying insects | <1 day | $15-25 |

| Water | Low-Moderate (20-31% overlap with traditional surveys) [13] | 2.4-3.1 | Low | 2-3 days | $35-55 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Soil eDNA Sampling and Processing Protocol

Sample Collection:

- Delineate agricultural field into 1-ha grid cells for systematic sampling

- Using a sterilized soil auger, collect 5-10 soil cores (0-15 cm depth) per sampling location

- Combine cores from each location to create a composite sample of approximately 300g [10]

- Store samples immediately in sterile Whirl-Pak bags on dry ice or blue ice for transport

- For temporal studies, collect samples at consistent phenological stages (e.g., pre-planting, peak growth, post-harvest)

DNA Extraction:

- Homogenize 10g subsamples using sterile mortar and pestle under controlled conditions

- Extract DNA using Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit with the following modifications [10] [11]:

- Extend bead-beating step to 10 minutes for improved cell lysis

- Include negative extraction controls to monitor contamination

- Quantify DNA yield using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer

- Assess DNA integrity via 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis

- Store extracts at -80°C until amplification

Metabarcoding Analysis:

- Amplify bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 785R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3') [10]

- Amplify fungal communities using ITS1F (5'-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3') and ITS2 (5'-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3')

- Perform PCR in 25µL reactions containing 12.5µL of 2× Taq PCR Master Mix, 0.5µM of each primer, and 1µL template DNA

- Use thermal cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, and 72°C for 1min, with final extension at 72°C for 5min [10]

- Purify PCR products using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit before sequencing on Illumina MiSeq platform (2×300 bp)

Figure 1: Soil eDNA processing workflow from field collection to data analysis

Airborne eDNA Sampling Protocol

Passive Air Sampling:

- Deploy passive samplers 1.5m above ground level at 3-5 locations per field [12]

- For spider web sampling: collect intact webs from field margins and structures using sterile forceps

- For leaf surface sampling: randomly select 30 leaves from throughout the canopy

- Expose PBS-moistened filter papers for 2 hours during peak biological activity (morning)

- Record meteorological conditions (temperature, humidity, wind speed) during sampling

Active Air Sampling:

- Use portable air filtration systems with 0.22-0.45 µm filters [14] [15]

- Draw air at standardized flow rates (150+ mL/min) for 30-60 minutes

- Deploy samplers along transects that account for prevailing wind patterns

- Include field blanks exposed for minimal duration to control for contamination

DNA Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract DNA using DNeasy PowerSoil Kit with extended incubation [10]

- For vertebrate detection: amplify 12S-V5 and 16S mam regions [12] [14]

- For arthropod detection: amplify COI gene using primers LCO1490 (5'-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3') and HCO2198 (5'-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3') [10]

- Use similar PCR conditions as soil protocol with annealing temperature adjusted to 50°C for COI

- Include positive controls (known DNA) and negative controls throughout the process

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for agricultural eDNA studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application | Key Features | Considerations for Agricultural Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit [10] [11] | All substrate types | Inhibitor removal technology | Optimal for humic-acid rich agricultural soils |

| DNA Extraction | MP Biomedicals FastDNA Spin Kit | Difficult-to-lyse organisms | Enhanced bead-beating | Effective for fungal spores and insect parts |

| PCR Amplification | Thermo Fisher Scientific Taq PCR Master Mix [10] | Metabarcoding PCR | Standardized formulation | Consistent performance across sample types |

| PCR Purification | QIAquick PCR Purification Kit [10] | Post-amplification clean-up | Remove primers, enzymes | Critical for high-quality sequencing libraries |

| Sampling Equipment | Sterivex 0.45µm filters [15] | Water and air sampling | Inline filtration | Compatible with various pump systems |

| Sampling Equipment | Sterile Whirl-Pak bags [10] | Soil and plant samples | Pre-sterilized | Prevent cross-contamination between samples |

| Quantification | Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 [10] | DNA concentration and purity | Minimal sample requirement | Essential for standardizing input DNA |

| Sequencing | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle) [10] | Metabarcoding sequencing | 2×300 bp reads | Optimal for 16S, ITS, and COI fragments |

Integrated Sampling Strategies

Multi-Substrate Approach for Comprehensive Assessment

Agricultural biodiversity monitoring benefits substantially from integrated substrate sampling that captures both above-ground and below-ground communities. Research demonstrates that combining soil, plant, and air sampling provides complementary biodiversity data that would be missed using single substrates [10] [11]. For instance, while soil eDNA effectively captures microbial and soil-dwelling organism diversity, airborne eDNA better reflects mobile pests and pollinators, and plant surface eDNA detects epiphytic microorganisms and direct pest interactions.

A structured multi-substrate sampling design should include:

- Stratified soil sampling based on management zones (e.g., crop rows vs. interrows, organic vs. conventional sections)

- Systematic plant sampling that accounts for canopy position and plant developmental stage

- Air sampling networks that consider elevation gradients and edge effects

- Temporal alignment across substrates to enable integrated data analysis

Case Study: Integrated Pest Management Monitoring

Research in Bangladesh demonstrated the power of eDNA metabarcoding for evaluating pest management strategies across different farming systems [10] [11]. The study compared organic, agroecological, and conventional farms, finding that organic systems supported higher microbial diversity (Shannon index = 3.87) while conventional systems had higher pest species richness (27 species). The integration of eDNA data with plant extract efficacy trials revealed that neem extract at 50% concentration achieved 91.3% mortality against Helicoverpa armigera, followed by garlic (85.7%) and tobacco (78.5%).

This approach exemplifies how multi-substrate eDNA analysis can directly inform sustainable agricultural practices by linking biodiversity assessments with management outcomes. The methodology enabled researchers to simultaneously monitor target pest populations, non-target effects on beneficial organisms, and soil microbial community responses to different intervention strategies.

Figure 2: Relationship between farming systems, eDNA substrates, and management outcomes

Quality Control and Methodological Considerations

Contamination Prevention

eDNA studies in agricultural environments require rigorous contamination controls due to the high potential for cross-contamination between samples and the presence of PCR inhibitors. Essential quality control measures include:

- Field controls: Process blank samples exposed to field conditions

- Extraction controls: Include negative controls during DNA extraction

- PCR controls: Incorporate no-template controls in all amplification runs

- Spatial separation: Physically separate pre- and post-PCR activities

- Equipment sterilization: Use bleach-based decontamination protocols for reusable equipment

Data Validation

Method validation should include:

- Positive controls: Known DNA samples to verify amplification efficiency

- Technical replicates: Assess methodological consistency

- Spike-in standards: Quantify potential inhibition and recovery efficiency

- Method comparison: Where possible, compare eDNA results with traditional monitoring data

- Database verification: Curate taxonomic assignments against validated reference databases

The protocols outlined herein provide a foundation for implementing robust eDNA monitoring in agricultural systems, enabling researchers to generate reproducible, high-quality data for assessing ecological communities across multiple substrates.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is a powerful molecular technique that combines high-throughput sequencing (HTS) with DNA barcoding to identify multi-species communities from complex environmental samples such as soil, water, or air [16]. This approach has revolutionized the monitoring of ecological communities by allowing researchers to characterize biodiversity without direct observation or capture of organisms, thereby reducing the need for taxonomic expertise and extensive fieldwork effort [17] [18]. In agricultural research, metabarcoding provides unprecedented insights into soil health, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem functioning by revealing the composition and dynamics of microbial and invertebrate communities that drive essential ecological processes [19] [20].

The core principle of metabarcoding lies in its ability to simultaneously amplify and sequence DNA barcode markers from multiple taxa within a sample, followed by bioinformatic analysis to assign these sequences to taxonomic groups. This methodology enables researchers to move beyond single-species detection to comprehensive community profiling, making it particularly valuable for assessing the impacts of agricultural management practices on soil biological communities and overall ecosystem health [19].

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Core Conceptual Framework

Metabarcoding operates on several key principles that distinguish it from traditional monitoring approaches. First, it leverages the fact that all organisms continuously shed DNA into their environment through skin cells, feces, mucus, or decomposition [16]. This environmental DNA persists in terrestrial ecosystems for varying durations—from days to years—depending on environmental conditions that affect degradation rates [16]. Second, the approach utilizes universal PCR primers that target conserved regions of taxonomic marker genes, flanking variable regions that provide species-level discrimination [20]. Finally, the quantitative potential of sequence data, while subject to biases, can provide insights into relative abundance patterns within communities when carefully calibrated and interpreted [17] [18].

The application of these principles in agricultural research allows for non-invasive monitoring of how farming practices affect soil nematode communities, microbial pathways, and overall ecosystem health indicators [19] [20]. For instance, tillage practices significantly influence nematode community structure and distribution within soil profiles, with different tillage regimes favoring distinct functional groups that indicate the health and stability of agricultural ecosystems [19].

Standardized Workflow Diagram

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standardized metabarcoding process from sample collection to data analysis, specifically tailored for agricultural soil samples:

Figure 1: Standardized metabarcoding workflow for agricultural soil samples, highlighting key stages from field collection to data analysis.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Collection and Processing for Agricultural Studies

Proper sample collection and processing are critical for obtaining representative metabarcoding data. In agricultural soil studies, samples should be collected using a standardized soil corer (typically 2.5 cm diameter) from multiple random locations within each plot [19]. For depth-stratified community analysis, cores should be divided into relevant depth increments (e.g., 0-5 cm and 5-20 cm) and pooled to create composite samples [19]. A minimum of 10 cores per composite sample is recommended to account for spatial heterogeneity.

Key considerations for agricultural samples:

- Timing: Sample during key agricultural phases (e.g., pre-planting, post-harvest) to capture management impacts

- Storage: Transport samples on dry ice and store at 4°C for short-term or -20°C for long-term preservation

- Homogenization: Sieve soils through a 5mm mesh to remove stones and debris, with thorough cleaning between samples

- Replication: Include multiple biological replicates (recommended n=4) per treatment to account for variability

For nematode community analysis specifically, subsequent extraction of nematodes from soil using centrifugation and sugar flotation methods is recommended prior to DNA extraction to enrich target organisms and reduce inhibitor content [19] [20].

DNA Extraction and Amplification Protocols

DNA extraction should be performed using commercial kits optimized for soil samples, with modifications as needed for difficult soils. The DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) has been successfully used in agricultural nematode studies, with an extended proteinase K digestion step (overnight at 55°C) to ensure complete lysis [19]. DNA concentration should be quantified using fluorometric methods (e.g., Nano spectrophotometer) to ensure sufficient template for library preparation.

For amplification of nematode communities, the 18S rRNA ribosomal gene provides optimal coverage and taxonomic resolution [20]. The primer pair NF1 (GGTGGTGCATGGCCGTTCTTAGTT) and 18Sr2b (TACAAAGGGCAGGGACGTAAT) targeting the V6-V8 regions has demonstrated excellent performance for nematode community profiling in agricultural systems [19]. PCR conditions should be optimized for the specific thermal cycler and reaction composition, typically involving 25-35 cycles with annealing temperatures between 55-60°C.

Quantitative Approaches: For quantitative applications, the qMiSeq approach incorporates internal standard DNAs to convert sequence read numbers to DNA copy numbers, accounting for sample-specific PCR biases [17]. This method enables more reliable cross-sample comparisons and correlation with traditional abundance measures.

Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Library preparation follows manufacturer protocols for the chosen sequencing platform, with Illumina MiSeq being commonly used for metabarcoding studies (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads recommended) [19]. Include appropriate controls (extraction blanks, PCR negatives) throughout the process to monitor contamination.

Bioinformatic processing typically involves:

- Demultiplexing: Assignment of reads to samples based on dual indexes

- Quality Filtering: Removal of low-quality reads and adapter sequences

- OTU Clustering: Grouping sequences into operational taxonomic units (≥97% similarity)

- Taxonomy Assignment: Using reference databases (e.g., curated nematode databases)

- Contamination Filtering: Removal of sequences present in negative controls

For agricultural applications, subsequent analysis should focus on calculating Nematode-Based Indices (NBIs) such as Maturity Index (MI), Structure Index (SI), Enrichment Index (EI), and Nematode Channel Ratio (NCR) to interpret ecological conditions [19] [20].

Quantitative Data in Metabarcoding Studies

Interpreting Sequence Data for Quantitative Assessment

The interpretation of sequence count data in metabarcoding studies represents a significant methodological consideration. While traditional approaches often convert sequence counts to presence/absence data (Frequency of Occurrence, FOO), there is growing evidence that Relative Read Abundance (RRA) can provide more accurate representations of population-level diet or community composition when appropriate controls are implemented [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Data Interpretation Approaches in Metabarcoding Studies

| Approach | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Occurrence (FOO) | Uses presence/absence based on count thresholds | Conservative; less affected by technical biases | Overestimates importance of rare taxa; sensitive to threshold selection | Species inventories; detection of rare taxa |

| Relative Read Abundance (RRA) | Uses proportion of sequence reads per taxon | Better reflects quantitative composition; more statistical power | Affected by primer biases, genome size, and amplification efficiency | Community comparisons; dominant taxa assessment |

| Quantitative MiSeq (qMiSeq) | Uses internal standards to estimate DNA copies | Accounts for sample-specific PCR efficiency; more quantitative | Requires additional controls and standardization | Absolute abundance estimation; cross-study comparisons |

The qMiSeq approach has demonstrated significant positive relationships between eDNA concentrations and both abundance (R²=0.81) and biomass of captured taxa in validation studies, supporting its utility for quantitative monitoring [17].

Agricultural Application Data

In agricultural contexts, metabarcoding has revealed significant tillage impacts on nematode communities. Research shows that beneficial free-living nematodes are most abundant in surface layers (0-5 cm), with >70% of populations concentrated in this zone, while herbivores dominate deeper soil layers (5-20 cm) [19]. Minimum tillage (MT) and no-tillage (NT) systems support 1.7 times higher bacterivore populations compared to conventional tillage (CT) at crop maturity stages [19].

Table 2: Nematode Community Responses to Tillage Practices in Corn-Soybean Systems

| Parameter | Conventional Tillage (CT) | Minimum Tillage (MT) | No-Tillage (NT) | Soil Depth Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterivores | Lower abundance | 1.7x higher than CT at maturity | Similar to MT | >70% at 0-5cm depth |

| Herbivores | 47-76% higher than MT/NT | Lower abundance | Lower abundance | Dominate at 5-20cm depth |

| Fungal-Feeding | Lower abundance | Intermediate | Higher abundance | NT shifts to fungal channel |

| Maturity Index | Initially high but declines | Stable | Increases over time | More stable in surface layers |

| Structure Index | Initially high but declines | Stable | Increases over time | Indicates food web complexity |

| Key Genera | Dominated by Pratylenchus | Balanced community | Balanced community | Rhabditis abundant in MT/NT |

These quantitative patterns demonstrate how metabarcoding can detect management impacts on soil biological communities, providing valuable indicators for agricultural sustainability assessment.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful metabarcoding requires careful selection of reagents and materials throughout the workflow. The following table details key solutions and their applications in agricultural metabarcoding studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabarcoding Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from nematode extracts | Extended proteinase K digestion (overnight, 55°C) improves yield |

| PCR Primers | NF1/18Sr2b primer pair | Amplification of 18S rRNA V6-V8 regions | Optimal for nematode community coverage; annealing ~58°C |

| Sequencing Kit | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 | 2×300 bp paired-end sequencing | Provides sufficient read length for 18S rRNA region |

| Quantification Standards | Synthetic DNA standards (qMiSeq) | Absolute quantification of sequence copies | Enables cross-sample comparisons and abundance estimates |

| Soil Nematode Extraction | Centrifugation-sucrose flotation | Separation of nematodes from soil particles | Reduces PCR inhibitors; improves DNA quality |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera XT Index Kit | Dual indexing for sample multiplexing | Allows pooling of multiple samples in single sequencing run |

| Quality Control | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, TapeStation | Quantification and quality assessment | Ensires adequate DNA concentration and fragment size |

| Reference Databases | Curated nematode 18S databases | Taxonomic assignment of sequences | Critical for accurate identification; requires regular updating |

Applications in Agricultural Ecological Monitoring

Metabarcoding provides powerful applications for monitoring agricultural ecosystems, particularly through the assessment of nematode communities as bioindicators of soil health. Nematodes occupy multiple trophic levels and respond predictably to environmental disturbances, making them ideal indicators for ecosystem structure and function [19] [20]. Key applications include:

Tillage Impact Assessment: Research has demonstrated that tillage practices significantly influence nematode community structure, with conventional tillage favoring herbivore nematodes (especially Pratylenchus), while minimum tillage and no-tillage systems support higher abundances of beneficial bacterivores [19]. These community shifts directly inform about nutrient cycling pathways and ecosystem stability.

Soil Health Monitoring: Metabarcoding enables calculation of Nematode-Based Indices (NBIs) including the Maturity Index (MI), Structure Index (SI), Enrichment Index (EI), and Nematode Channel Ratio (NCR) [19] [20]. These indices provide integrated measures of soil food web condition, with MI indicating disturbance levels, SI measuring food web complexity, and NCR distinguishing between bacterial and fungal decomposition pathways.

Management Practice Optimization: By revealing how agricultural practices affect soil biological communities, metabarcoding data can guide management decisions toward more sustainable approaches. For instance, the dynamic response of nematode communities to occasional tillage within no-tillage systems helps balance the benefits of conservation practices with practical agronomic needs in clayey soils [19].

The integration of metabarcoding into agricultural monitoring frameworks represents a significant advancement in our ability to assess and manage soil health, providing comprehensive biological data that complements traditional physical and chemical indicators.

Global food production systems are under unprecedented pressure from population growth and climate change, making the monitoring of agricultural biodiversity more critical than ever [21]. Biodiversity supports essential ecosystem functions such as pollination, pest control, and soil fertility maintenance, which are fundamental to productive agriculture. However, traditional biodiversity monitoring methods often fail to capture the full complexity of agricultural ecosystems, creating a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of how farming practices affect ecological communities.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding represents a transformative approach for profiling multi-trophic biodiversity in agricultural landscapes [10]. This novel technique detects genetic material shed by organisms into their environment (e.g., soil, water, air), allowing for comprehensive biodiversity assessment without the need for direct observation or trapping. The application of eDNA metabarcoding in agricultural research enables scientists to explore agro-biodiversity and microbial dynamics at unprecedented scales and resolutions, providing crucial insights for developing sustainable pest management strategies and enhancing food security [10].

The eDNA Metabarcoding Advantage in Agricultural Systems

Technical Foundations and Capabilities

eDNA metabarcoding combines environmental DNA sampling with high-throughput sequencing to identify multiple taxa simultaneously from environmental samples [16]. This approach leverages the fact that all organisms continuously shed genetic material (e.g., through skin cells, feces, mucus, pollen) into their surroundings. In agricultural contexts, this genetic material can be collected from soil, irrigation water, plant surfaces, and even air samples, providing a holistic picture of the agricultural ecosystem [10].

The technique primarily uses two genetic markers for identification: the 16S rRNA gene for bacteria and archaea, and the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene for pest species and other eukaryotes [10]. These standardized genetic regions allow for taxonomic classification across diverse organismal groups, from soil microbes to invertebrate pests and beneficial insects.

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Traditional biodiversity monitoring in agricultural systems typically relies on visual surveys, trapping, and morphological identification, which are often labor-intensive, taxonomically biased, and limited in temporal and spatial resolution [16]. In contrast, eDNA metabarcoding offers several distinct advantages:

- Comprehensive taxonomic coverage: From microorganisms to mammals in a single sample [22]

- High sensitivity: Detection of rare, cryptic, or elusive species [16]

- Non-invasiveness: Minimal disturbance to crops and wildlife [10]

- Standardization: Reproducible protocols across different agricultural contexts [22]

- Cost-effectiveness: Reduced labor requirements compared to traditional surveys [22]

- Archival value: Samples can be stored for future reanalysis [16]

Recent research demonstrates that organic farming systems exhibit significantly higher microbial diversity (Shannon index = 3.87) compared to conventional systems, while conventional farms recorded the highest pest species diversity (species richness = 27) [10]. These findings highlight how different agricultural practices shape distinct ecological communities, knowledge that is essential for developing targeted management strategies.

Application Note: Integrated Pest Management and Biodiversity Assessment

Experimental Design and Workflow

A recent study investigated the integration of plant-based pest control methods with eDNA metabarcoding to develop eco-friendly pest management strategies [10]. The research employed a comparative approach across organic, agroecological, and conventional farms in Bangladesh, collecting soil, plant, and air samples for eDNA analysis while testing the efficacy of botanical pesticides against Helicoverpa armigera, a major agricultural pest.

The following workflow illustrates the integrated experimental design:

Key Findings and Implications

The study revealed significant differences in biodiversity patterns across farming systems and demonstrated the efficacy of plant-derived pesticides:

Table 1: Biodiversity Indicators Across Agricultural Management Systems

| Management System | Microbial Diversity (Shannon Index) | Pest Species Richness | Dominant Microbial Taxa | Key Pest Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic | 3.87 | 18 | Beneficial decomposers | Helicoverpa armigera |

| Agroecological | 3.45 | 22 | Mixed community | Spodoptera litura |

| Conventional | 2.91 | 27 | Reduced diversity | Multiple pest species |

Table 2: Efficacy of Botanical Pesticides Against H. armigera

| Plant Extract | Concentration | Mortality Rate (%) | Time to 50% Mortality (hours) | Impact on Non-Target Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neem | 10% | 68.2 | 48 | Low |

| 25% | 82.7 | 36 | Low | |

| 50% | 91.3 | 24 | Moderate | |

| Garlic | 10% | 59.8 | 52 | Low |

| 25% | 74.3 | 42 | Low | |

| 50% | 85.7 | 30 | Low | |

| Tobacco | 10% | 52.4 | 60 | Low |

| 25% | 67.9 | 48 | Moderate | |

| 50% | 78.5 | 36 | High |

Statistical analysis using One-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test confirmed significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments and controls, validating the effectiveness of this integrated approach [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Field Sampling and eDNA Collection

Materials Required:

- Sterile Whirl-Pak bags

- Sterilized soil auger (0-15 cm depth)

- Sterile scissors and polyethylene bags for plant samples

- PBS-moistened filter paper for air sampling

- Cooler with ice packs for sample transport

- GPS unit for geolocation recording

Procedure:

- Site Selection: Identify representative plots (10 m × 10 m) within each farming system with a minimum 10 m buffer between plots to reduce edge effects [10].

- Soil Sampling: Collect three sub-samples diagonally from each plot at 0-15 cm depth using a sterilized soil auger. Pool sub-samples to form one composite sample (~300 g). Store in sterile Whirl-Pak bags on ice [10].

- Plant Sampling: Clip leaf and stem tissues (~5 g) from plants showing visible signs of pest infestation using sterile scissors. Place in labeled, sterile polyethylene bags [10].

- Air Sampling: Expose PBS-moistened filter papers for 2 hours at 1.5 m height to capture airborne microbes and particulates. Use triplicate plates with negative controls (unexposed plates) processed alongside each batch to detect contamination [10].

- Sample Preservation: Transport all samples to the laboratory on ice and store at -20°C until DNA extraction.

Laboratory Analysis: DNA Extraction and Metabarcoding

Materials Required:

- Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Cat. No. 12888)

- NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- PCR reagents and thermal cycler

- Illumina MiSeq platform

- Primers: 16S rRNA (341F/785R) and COI (LCO1490/HCO2198)

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract eDNA from soil, plant surface, and air samples using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit following manufacturer's instructions, with bead-beating for 10 minutes to enhance cell lysis [10].

- Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration and purity using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Check integrity by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis [10].

- PCR Amplification:

- For microbial analysis: Amplify V3–V4 region of 16S rRNA gene using primers 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 785R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) [10].

- For pest identification: Amplify 658 bp fragment of COI gene using primers LCO1490 (5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′) [10].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify PCR products using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit. Sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform (2×300 bp) following standard protocols [10].

- Quality Control: Include positive controls (extracted DNA from Escherichia coli and Helicoverpa armigera) and No-template Controls (NTCs) in each PCR run to detect contamination [10].

Bioassay for Pest Management Efficacy

Materials Required:

- Neem (Azadirachta indica), garlic (Allium sativum), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plant materials

- Solvents for extraction (ethanol, water)

- Helicoverpa armigera larvae colonies

- Artificial diet or host plants

- Greenhouse facilities with controlled conditions

Procedure:

- Plant Extract Preparation: Prepare extracts from neem, garlic, and tobacco using appropriate solvents (ethanol or water) at concentrations of 10%, 25%, and 50% [10].

- Insect Rearing: Maintain H. armigera colonies on artificial diet or host plants under controlled conditions (25±2°C, 65±5% RH, 14:10 L:D photoperiod) [10].

- Treatment Application: Apply plant extracts to H. armigera larvae using standardized methods (e.g., leaf-dip bioassay or direct application). Include untreated controls and synthetic pesticide treatments for comparison [10].

- Data Collection: Record mortality rates at 24, 48, and 72 hours post-treatment. Calculate corrected mortality using Abbott's formula if necessary [10].

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze data using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test to determine significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural eDNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Product | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex matrices | Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | Optimal for inhibitor-rich soil samples; includes bead-beating step [10] |

| PCR Master Mix | Amplification of target DNA regions | Thermo Fisher Scientific Taq PCR Master Mix | Provides consistent performance for metabarcoding applications [10] |

| Sequencing Platform | High-throughput DNA sequencing | Illumina MiSeq | 2×300 bp configuration ideal for 16S and COI amplicons [10] |

| Universal Primers | Amplification of taxonomic marker genes | 16S: 341F/785RCOI: LCO1490/HCO2198 | Standardized primers enable cross-study comparisons [10] |

| Plant Extraction Solvents | Extraction of bioactive compounds | Ethanol, distilled water | Different solvents extract different compound classes; water extracts often show lower non-target effects [10] |

| Bioassay Materials | Efficacy testing of pest management | Artificial diet, rearing containers | Standardized conditions essential for reproducible results [10] |

| LYG-202 | LYG-202, CAS:1175077-25-4, MF:C25H30N2O5, MW:438.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (Rac)-Epoxiconazole | Epoxiconazole | Epoxiconazole is a broad-spectrum triazole fungicide for plant disease control research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or animal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Data Integration and Analysis Framework

The power of eDNA metabarcoding in agricultural research lies in integrating biodiversity data with management outcomes. The following conceptual framework illustrates how to translate raw data into actionable insights:

The integration of eDNA metabarcoding with agricultural research represents a paradigm shift in how we monitor and manage biodiversity in food production systems. This approach provides unprecedented insights into the complex interactions between farming practices, ecological communities, and ecosystem functions that underpin food security.

Future applications of eDNA metabarcoding in agriculture should focus on:

- Developing standardized protocols for different agricultural contexts and regions [22]

- Establishing long-term monitoring networks to track biodiversity changes in response to management practices and climate change [22]

- Integrating eDNA data with remote sensing and other technologies for multi-dimensional ecosystem assessment [22]

- Expanding reference databases to improve taxonomic resolution, particularly for understudied agricultural regions [21]

As the technology continues to advance and become more accessible, eDNA metabarcoding promises to play an increasingly vital role in guiding the transition toward more sustainable, productive, and resilient agricultural systems worldwide. By embracing this powerful tool, researchers, farmers, and policymakers can make informed decisions that simultaneously address food security and biodiversity conservation challenges.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a transformative tool for monitoring biodiversity, enabling the detection of species from genetic material shed into their environment [2]. This review examines the application of eDNA metabarcoding within agricultural ecosystems, framing it within a broader thesis on monitoring agricultural ecological communities. While eDNA approaches have seen rapid adoption in aquatic and marine systems [13] [2], their application to agricultural landscapes reveals significant methodological gaps and a pronounced bias in global implementation. Agricultural systems present unique challenges and opportunities for eDNA monitoring, from tracking pest populations and beneficial organisms to assessing soil health and the impacts of management practices [20] [10] [23]. This article provides a critical analysis of the current landscape, summarizes quantitative findings from key studies into structured tables, details essential experimental protocols, and visualizes core workflows to support researchers in advancing this field.

The Agricultural eDNA Gap and Global Bias

The potential of eDNA metabarcoding in agriculture is immense, yet its application remains uneven and methodologically heterogeneous. Current evidence indicates a significant gap between technological capability and systematic agricultural implementation.

Table 1: Documented Global Applications of eDNA Metabarcoding in Agriculture

| Region/Country | Study Focus | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Integrated pest management; microbial dynamics | Organic farms had highest microbial diversity (Shannon Index=3.87); conventional farms had highest pest richness (27 species) | [10] |

| Canada | Farmland arthropod biodiversity and pest monitoring | 7,707 arthropod species detected; 231 registered pest species identified; community composition influenced more by site than crop | [23] |

| United Kingdom | National terrestrial biodiversity using airborne eDNA | 1,120+ taxa identified via air quality networks; complementary to citizen science data | [14] |

| Netherlands | Freshwater macroinvertebrate biomonitoring protocols | Aggressive-lysis of sorted samples showed 70% community overlap with morphology; eDNA only 20% | [13] |

| Global (Review) | Ecosystem biodiversity detection | eDNA is a sensitive, efficient complement to traditional methods; accuracy affected by environmental factors | [2] |

A critical analysis reveals a twofold challenge. Firstly, a methodological gap persists; no single standardised protocol exists for agricultural settings. Studies use different sampling strategies (soil, water, air, specimens), DNA extraction methods (destructive vs. non-destructive), and bioinformatic pipelines, complicating cross-study comparisons [20] [13]. Secondly, a geographical application bias is evident. While research and infrastructure are advancing in North America and Europe [14] [23] [24], large-scale, standardised applications in developing regions, which often host the most biodiversity-rich agricultural landscapes, are limited. The study from Bangladesh [10] represents a notable exception, highlighting the potential for eDNA to guide sustainable pest management in diverse agroecological contexts.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Agricultural eDNA

Bridging the identified gaps requires robust, standardised methodologies. The following sections detail protocols for key applications in agricultural research.

Protocol 1: Soil Nematode Community Analysis for Soil Health Assessment

Nematodes are critical bioindicators of soil food web structure and ecosystem function. The following workflow provides a standardised method for generating nematode-based indices (NBIs) from soil samples [20].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect composite soil samples using a sterilized soil auger from the top 0-15 cm. A minimum of three sub-samples per field is recommended, pooled into a sterile Whirl-Pak bag and immediately stored on ice [10].

- Nematode Elutriation: Extract nematodes from large soil quantities (e.g., 100-300 g) using centrifugal-flotation or Baermann funnel techniques to separate organisms from soil particles [20].

- DNA Extraction: Perform bulk DNA extraction on the nematode elutriate. The Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit is widely used and effective. Include bead-beating (e.g., 10 minutes) to ensure adequate cell lysis of tough nematode cuticles [20] [10].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the 18S rRNA gene region using the primers NF1 (5'-GCGGTAATTCCAGCTCCAAT-3') and 18Sr2b (5'-CCTTCCGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3'). These primers provide optimal coverage and taxonomic resolution for nematodes [20].

- PCR Mix (25 µL): 12.5 µL of 2× Taq PCR Master Mix, 0.5 µM of each primer, 1 µL (~10 ng) of template DNA, and nuclease-free water.

- Thermal Cycling: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [10].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Purify PCR products and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2×300 bp). Process sequences using a pipeline like QIIME2. Assign taxonomy against a curated nematode-specific reference database (e.g., curated SILVA or PR2) for accurate NBI calculation [20].

Protocol 2: Airborne eDNA for Large-Scale Terrestrial Biodiversity Monitoring

Leveraging existing air quality monitoring networks allows for unprecedented continental-scale biodiversity assessment. This protocol is adapted from the first national-scale airborne eDNA survey [14].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Utilize active air samplers from national ambient air quality monitoring networks. These devices draw air through particulate filters (e.g., PM10, PM2.5), which trap airborne eDNA. No modification to standard network operation is required [14].

- DNA Extraction: Carefully remove a portion of the particulate filter using a sterile punch. Extract DNA using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Kit, following standard protocols [14].

- Multi-Marker PCR Amplification: To maximize biodiversity recovery, amplify multiple genetic markers in parallel reactions [14]. Using only one marker can miss a significant portion of the community.

- For Vertebrates: Use both 12S and 16S rRNA primers for comprehensive coverage, as they recover non-overlapping sets of species.

- For Arthropods/Plants/Fungi: Use the COI gene (primers LCO1490/HCO2198) and ITS regions.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Pool amplified products after purification and sequence on an Illumina platform. Process data bioinformatically to assign sequences to taxa. Compare detections with complementary data sources like citizen science records to validate and contextualize findings [14].

Protocol 3: Freshwater Macroinvertebrate Biomonitoring

Macroinvertebrates are key indicators of water quality in agricultural landscapes. This protocol compares different DNA extraction approaches against traditional morphology [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Freshwater Macroinvertebrate Monitoring Protocols

| Protocol Step | Morphology (Gold Standard) | Aggressive-Lysis (Destructive) | Soft-Lysis (Non-Destructive) | eDNA from Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Live-sorted specimens | Live-sorted specimens | Live-sorted specimens | Filtered water |

| DNA Source | Not applicable | Homogenized tissue | Preservative/lysis buffer | Environmental DNA |

| Community Overlap with Morphology | 100% | 70% ± 6% | 58% ± 7% | 20% ± 9% |

| Key Advantage | Taxonomic verification; gold standard | High similarity to morphology | Voucher specimens preserved | No sorting required; fast |

| Key Disadvantage | Labor-intensive; requires expertise | Specimens destroyed | Lower DNA yield for hard-bodied taxa | Low overlap with traditional methods |

Step-by-Step Methodology (Aggressive-Lysis Approach):

- Field Collection: Collect macroinvertebrates using standard pond-net sweeps in drainage ditches or streams. Preserve one sample in 96% ethanol for DNA analysis and a parallel sample for morphological identification.

- Sample Sorting and Lysis: Live-sort specimens from debris in the field. For the aggressive-lysis protocol, transfer sorted specimens to a tube with lysis buffer and incubate overnight at 56°C with gentle shaking [13].

- DNA Extraction and PCR: Extract DNA from the lysate using a membrane-based protocol (e.g., Pall Corporation Acroprep plates). Amplify the COI barcode region using primers such as LCO1490/HCO2198.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform. Compare metabarcoding results to the morphological identification from the parallel sample to validate and calibrate the molecular data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful eDNA metabarcoding relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for agricultural applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Agricultural eDNA

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from complex samples (soil, filters, debris) | Effective for inhibiting substance removal; includes bead-beating step [10]. |

| NF1/18Sr2b Primers | Amplification of 18S rRNA for nematode and microeukaryote communities | Provides optimal coverage and taxonomic resolution for NBIs [20]. |

| LCO1490/HCO2198 Primers | Amplification of COI gene for arthropod and pest identification | Standard barcode marker for animal species; used for pest detection [10] [23]. |

| 341F/785R Primers | Amplification of 16S rRNA V3-V4 region for bacterial community analysis | Used for soil and plant microbiome studies [10]. |

| Illumina MiSeq System | High-throughput sequencing of amplicon libraries | Standard platform for metabarcoding; 2x300 bp provides sufficient read length. |

| Sylphium eDNA Dual Filter Capsule | Standardized filtration of water samples for aquatic eDNA | 0.8 µm pore size; allows consistent processing of water volumes [13]. |

| BOLD/GenBank Databases | Reference databases for taxonomic assignment of sequences | Completeness and curation are critical for accurate identification [23]. |

| QIIME2 Platform | Bioinformatic pipeline for processing raw sequence data | From demultiplexing to diversity analysis; widely supported [10]. |

| Impurity F of Calcipotriol | Impurity F of Calcipotriol, CAS:112875-61-3, MF:C39H68O3Si2, MW:641.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bupropion morpholinol-d6 | Bupropion morpholinol-d6, CAS:1216893-18-3, MF:C13H18ClNO2, MW:261.78 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

From Lab to Field: Methodological Protocols and Practical Applications in Agriculture

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a revolutionary tool for monitoring ecological communities, offering a sensitive, non-invasive, and comprehensive alternative to traditional survey methods. In agricultural landscapes, understanding the complex interactions between crops, pests, soil microbes, and beneficial organisms is vital for sustainable management. The foundation of any successful eDNA study lies in the strategic selection and sampling of environmental substrates—soil, water, and air—each providing a unique window into the agricultural ecosystem. The adoption of eDNA technology in soil health monitoring has seen a rapid increase, with more than 700 publications on soil eDNA methods since 2001 and an annual growth rate of over 20% since 2017 [25]. This application note provides detailed protocols for the strategic sampling of these substrates, framed within the context of monitoring agricultural ecological communities.

Soil eDNA: Capturing the Rhizosphere Revolution

Soil serves as a massive reservoir of environmental DNA, providing critical insights into microbial dynamics, pest presence, and overall soil health. The eDNA concentration in soil is abundant, accounting for roughly 40% of the total DNA pool, with estimated content ranging from 0.03 to 200 µg/g [2]. Soil health is essential for sustainable agricultural practices, biodiversity conservation, and ecosystem functioning, with eDNA technology revolutionizing soil health monitoring by enabling sensitive, non-invasive assessments of soil biodiversity [25].

Strategic Sampling Protocol for Agricultural Soils

- Site Selection: Based on a study comparing farming practices, establish replicate plots (e.g., 10 m × 10 m) within each farm type (organic, conventional, agroecological) with a minimum 10 m buffer between plots to reduce edge effects and spatial autocorrelation [10].

- Collection Technique: Using a sterilized soil auger, collect samples at a depth of 0-15 cm. From each plot, collect three sub-samples (approximately 100 g each) diagonally and pool to form one composite sample (~300 g) [10].

- Spatial Considerations: Sample distribution should be higher in the upper soil layers where eDNA is most abundant, noting that eDNA concentration decreases with increasing depth [2].

- Storage and Preservation: Store composite samples in sterile Whirl-Pak bags and keep on ice immediately after collection. For DNA preservation, use a liquid preservative such as ethanol for storing eDNA on filters at room temperature when refrigeration is not feasible in field conditions [26].

Table 1: Soil eDNA Concentration Variations Across Environments

| Soil Type/Environment | eDNA Concentration | Key Factors Influencing Detection |

|---|---|---|

| General Soil | 0.03 - 200 µg/g [2] | Soil composition, organic matter, pH, microbial activity [2] |

| Haihe River Sediments | 96.8 ± 19.8 µg/g [2] | Particle adsorption, protection from nuclease destruction [2] |

| Ferruginous Sediments (Lake Towuti) | 0.5-0.6 µg/g (surface layer) [2] | Depth, oxidation conditions, mineral composition |

| Agricultural Soils | Highly Variable | Farming practice (organic vs. conventional), crop type, pesticide use [10] |

Water eDNA: Liquid Biopsies for Agricultural Ecosystems

In agricultural contexts, water eDNA can be collected from irrigation channels, ponds, runoff collection areas, and subsurface drainage, providing information about water-borne pathogens, nutrient cycling microbes, and aquatic pests. eDNA analysis enables the identification of organisms without direct observation, making it particularly valuable for detecting rare or invasive species in aquatic agricultural environments [2].

Strategic Sampling Protocol for Agricultural Waters

- Sample Volume: For most agricultural applications, 1 or 2 L of water is typically collected, as this volume has been established as optimal for filtration and concentrating DNA from water samples [26].

- Collection Method: Collect water samples in sterile bottles. For surface waters in irrigation channels or ponds, sample from approximately 10-15 cm below the surface to avoid surface debris [26].

- Filtration Protocol: Filter water samples through 0.7-μm glass fiber filters, which have been identified as the most common and effective filter material for eDNA capture [26]. Filtration can be performed on-site or in the laboratory:

- On-site filtration is beneficial for eDNA preservation but requires portable equipment.

- Laboratory filtration is preferable when processing large sample numbers or turbid water.

- Timing Considerations: The sampling-to-filtering steps should be completed within 24 hours of collection. For remote survey sites, filter locally to reduce transportation time and costs [26].

Table 2: Water Sampling and Filtration Parameters for Agricultural Applications

| Parameter | Recommended Specification | Agricultural Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | 1-2 L [26] | Adjust based on target organism abundance and water body size |

| Filter Pore Size | 0.7 μm glass fiber filters [26] | Effective for capturing fish DNA (1-10 μm particles) [26] |

| Filtration Location | Field (preferred) or lab | Field filtration prevents eDNA decay during transport [26] |

| Processing Time | Within 24 hours [26] | Extended times reduce DNA quality and detection sensitivity |

| Sample Replicates | ≥3 per site [26] | Accounts for spatial heterogeneity in agricultural water bodies |

Airborne eDNA: The Frontier of Aerobiome Monitoring

Airborne eDNA represents an emerging frontier in agricultural monitoring, particularly for tracking pathogen dispersal, pollen flow, and aerial pest movements. This substrate offers unique insights into the aerobiome of agricultural ecosystems, complementing information obtained from soil and water sampling.

Strategic Sampling Protocol for Agricultural Airborne eDNA

- Collection Method: Employ passive sampling systems using PBS-moistened filter papers. Position collection plates at approximately 1.5 m height to align with crop canopy level [10].

- Exposure Duration: Utilize a 2-hour exposure period following guidelines for standard bioaerosol sampling in field conditions [10].

- Quality Control: Implement triplicate plates and process negative controls (unexposed plates) alongside each batch to detect potential contamination [10].

- Sample Processing: Extract DNA from exposed filters using the same methodologies as for soil and water samples, with appropriate modifications for the expected lower biomass.

Agricultural eDNA Sampling Workflow

Integrated Experimental Design for Agricultural Monitoring

Strategic substrate selection should be guided by specific research questions in agricultural contexts. Different substrates reveal complementary aspects of the agricultural ecosystem, and an integrated approach provides the most comprehensive understanding.

Substrate Selection Framework

- Soil eDNA: Essential for monitoring soil health, microbial communities, root-associated pathogens, and soil-dwelling pests. A study comparing farming systems found organic farms exhibited the highest microbial diversity (Shannon index = 3.87), demonstrating the value of soil eDNA for assessing farming practice impacts [10].

- Water eDNA: Ideal for detecting aquatic pathogens, irrigation-borne diseases, and organisms in agricultural water systems. The qMiSeq approach for water eDNA has shown significant positive relationships between eDNA concentrations and both abundance and biomass of captured taxa [17].

- Airborne eDNA: Crucial for monitoring aerial pathogen dispersal, pollen flow, and flying insect pests. This emerging substrate provides real-time information about airborne communities that affect crop health.

Table 3: Comparative eDNA Detection Metrics Across Agricultural Substrates

| Metric | Soil | Water | Air |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Yield Range | 0.03-200 µg/g [2] | 2.5-88 µg/L [2] | Variable (typically lower) |

| Primary Agricultural Targets | Microbial communities, nematodes, soil pests | Pathogens, aquatic pests, runoff indicators | Fungal spores, pollen, airborne pests |

| Spatial Resolution | High (localized) | Moderate (influenced by flow) | Low (broad dispersal) |

| Temporal Resolution | Weeks to months [2] | Days to weeks [2] | Hours to days |

| Detection of Rare Species | Moderate to High | Moderate | Challenging |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust eDNA protocols requires specific laboratory reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for agricultural eDNA studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural eDNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | Cat. No. 12888 [10] | Optimal extraction for soil samples with inhibitors |

| Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit | - [26] | High-quality eDNA extraction for filters |

| Glass Fiber Filters | 0.7 μm pore size [26] | eDNA capture from water samples |

| 341F/785R Primers | 16S rRNA V3-V4 region [10] | Amplification of bacterial communities |

| LCO1490/HCO2198 Primers | COI gene, 658 bp [10] | Detection of pest arthropods |

| Illumina MiSeq Platform | 2×300 bp configuration [10] | High-throughput sequencing |

| SterivexTM-GP Filter Units | 0.22 μm pore size [26] | Closed-system filtration for field collection |

| 1alpha, 25-Dihydroxy VD2-D6 | 1alpha, 25-Dihydroxy VD2-D6, CAS:216244-04-1, MF:C28H44O3, MW:434.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,4-Dibromo-Mal-PEG2-N-Boc | 3,4-Dibromo-Mal-PEG2-N-Boc, MF:C15H22Br2N2O6, MW:486.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quality Assurance and Data Standardization

Ensuring data quality and interoperability is paramount in eDNA studies, particularly for long-term agricultural monitoring. Adherence to standardized protocols and metadata recording enables cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses.

Critical Quality Control Measures

- Field Controls: Include field blanks (e.g., cooler blanks) and negative controls during sampling to detect contamination [17].

- Laboratory Controls: Implement extraction blanks, PCR negative controls, and positive controls throughout laboratory processing [10].

- Inhibition Testing: Assess sample inhibition through spiked internal controls or dilution series [26].

- Metadata Documentation: Follow standardized frameworks such as the FAIR eDNA (FAIRe) metadata checklist, which incorporates terms from MIxS, Darwin Core, and eDNA-specific fields [27].

eDNA Quality Assurance Framework

Application in Agricultural Research: A Case Study

A recent study leveraging eDNA metabarcoding across organic, agroecological, and conventional farms in Bangladesh demonstrates the power of integrated substrate sampling. Researchers collected soil, plant, and air samples from each farming system and used eDNA metabarcoding to analyze microbial and pest diversity [10]. The findings revealed that organic farms exhibited the highest microbial diversity (Shannon index = 3.87), while conventional farms recorded the highest pest species diversity (species richness = 27) [10]. This integrated eDNA approach provided a comprehensive view of how farming practices influence agro-ecosystem composition, enabling more targeted pest management strategies.

When combined with bioassays of plant extracts against major pests like Helicoverpa armigera, the eDNA data helped contextualize treatment efficacy within the broader ecosystem context. Neem extract at 50% concentration achieved the highest mortality rate (91.3%), followed by garlic (85.7%) and tobacco (78.5%), demonstrating how eDNA monitoring can inform the selection of effective plant-based pesticides [10].

Strategic substrate selection—soil, water, and air—forms the foundation of robust agricultural eDNA monitoring programs. Each substrate offers unique insights into different components of agricultural ecosystems, from soil microbial communities to airborne pathogen dispersal. By implementing the standardized protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can generate comparable, high-quality data that tracks agricultural community dynamics across space and time. The integration of eDNA metabarcoding with emerging technologies such as GIS and remote sensing is expected to further expand its applications in agricultural monitoring, providing real-time, large-scale insights into ecosystem health and resilience [25]. As agricultural systems face increasing pressures from climate change, pest invasions, and sustainability demands, eDNA approaches will play an increasingly vital role in guiding evidence-based management decisions that balance productivity with ecological preservation.