Harnessing Microbial Communities: Engineering Consortia for Sustainable Biotech Applications

This article explores the emerging field of community-level engineering, where designed microbial consortia are leveraged for advanced, sustainable biotechnological applications.

Harnessing Microbial Communities: Engineering Consortia for Sustainable Biotech Applications

Abstract

This article explores the emerging field of community-level engineering, where designed microbial consortia are leveraged for advanced, sustainable biotechnological applications. We cover the foundational principles of synthetic ecology, from top-down and bottom-up design strategies to the ecological interactions that govern community function. The article details practical methodologies for constructing and optimizing consortia, including the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle and metabolic modeling. It further addresses critical challenges in biosafety, biosecurity, and real-world deployment, while validating these approaches through comparative analysis of their applications in bioproduction, bioremediation, and healthcare. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future directions for harnessing the power of microbial communities.

The Principles of Synthetic Ecology: From Single Organisms to Complex Consortia

Defining Community-Level Engineering and its Biotechnological Promise

Community-Level Engineering (CLE) is an advanced biotechnological approach focused on the design, construction, and manipulation of microbial consortia to perform complex functions that are challenging or impossible for single-strain systems. This field moves beyond monoculture engineering to harness the power of synergistic interactions between different microbial species, creating systems with distributed metabolic pathways, enhanced stability, and emergent functionalities [1] [2]. CLE represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, drawing inspiration from natural microbial ecosystems where division of labor, syntrophic interactions, and metabolic cross-feeding enable sophisticated community-level behaviors [3]. The core premise of CLE is that microbial communities can be engineered as integrated biological systems with capabilities exceeding the sum of their individual components, offering transformative potential for sustainable biotechnology applications across environmental remediation, biomanufacturing, and therapeutic development.

Key Principles and Ecological Interactions

Engineering functional microbial communities requires a fundamental understanding of the ecological interactions that govern community assembly, stability, and function. These multidimensional interactions create the framework for designing consortia with predictable behaviors and optimized performance characteristics.

Table 1: Ecological Interactions in Engineered Microbial Consortia

| Interaction Type | Ecological Relationship | Metabolic Basis | Engineering Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commensalism | (0/+) | Food chain metabolism | Staged biotransformations; precursor feeding |

| Competition | (-/-) | Substrate competition | Population control; niche specialization |

| Predation | (-/+) | Food chain with waste | Community dynamics regulation |

| Cooperation | (+/+) | Syntrophy | Distributed metabolic pathways |

| Amensalism | (0/-) | Waste product inhibition | Population balancing; pathway regulation |

| No Interaction | (0/0) | No common metabolites | Functional modularity; orthogonal processes |

These ecological interactions form the foundation for engineering stable consortia, with syntrophic cooperation (+/+) being particularly valuable for distributing metabolic burden and combining specialized capabilities across different microbial chassis [1] [2]. Engineering these interactions enables the creation of consortia with division of labor, where complex biochemical tasks are partitioned among community members to reduce metabolic load and improve overall efficiency [2].

Quantitative Framework for Community Design

The engineering of microbial consortia requires careful consideration of quantitative parameters that govern community composition, functional output, and stability. The following data synthesized from multiple studies provides key design constraints and performance metrics.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Community-Level Engineering

| Parameter | Value Range | Impact on Community Function | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Species Richness | 2-10 species | Enables division of labor while maintaining controllability | 16S rRNA sequencing; flow cytometry |

| Optimal Inoculation Ratio | 1:1 to 1:100 | Determines initial community structure and long-term stability | Fluorescent labeling; selective plating |

| Metabolic Load Reduction | 30-70% | Distributed pathway burden compared to single chassis | Growth rate analysis; proteomics |

| Community Stability | 15-100 generations | Duration of maintained function without intervention | Population tracking; functional assays |

| Productivity Enhancement | 2-5 fold | Increased output compared to monoculture systems | Metabolite quantification; HPLC |

| Communication Efficiency | nM-μM AHL concentrations | Quorum sensing signal potency for coordination | LC-MS; reporter assays |

These quantitative parameters provide essential design constraints for developing robust microbial consortia. The data indicates that even minimal communities of 2-10 species can achieve significant functional improvements, with optimal inoculation ratios being highly dependent on the specific ecological interactions being engineered [2]. The substantial reduction in metabolic load (30-70%) demonstrates one of the most significant advantages of CLE approaches, enabling the implementation of complex pathways that would be untenable in single organisms [2].

Experimental Protocols for Community-Level Engineering

Protocol: DBTL Cycle for Microbial Consortia Development

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) framework provides an iterative methodology for engineering robust microbial communities with predictable functions [3]. This systematic approach enables continuous refinement of consortia design based on experimental data.

Design Phase

- Objective Definition: Clearly specify the functional goal (e.g., target compound production, pollutant degradation)

- Top-Down Design: For complex functions, select environmental parameters (substrate loading, dilution rates, physicochemical conditions) to drive ecological selection toward desired metaphenotypes

- Bottom-Up Design: For well-characterized systems, select specific microbial strains based on genomic and metabolic capabilities; reconstruct metabolic networks using tools like flux balance analysis (FBA)

- Interaction Mapping: Define required ecological interactions (Table 1) and potential communication networks

- Theoretical Modeling: Develop computational models predicting community behavior using constraint-based modeling or agent-based simulations

Build Phase

- Strain Selection: Curate microbial chassis from culture collections or environmental isolates based on design parameters

- Genetic Modification: Implement synthetic biology tools (CRISPR, recombinering) to introduce or enhance desired functions

- Communication Engineering: Incorporate cell-cell signaling systems (e.g., lux, las, or synthetic quorum sensing systems) for population coordination

- Consortia Assembly: Combine strains at specified inoculation ratios (Table 2) in appropriate growth media

- Spatial Structuring: Implement encapsulation, biofilm systems, or microfluidic devices when spatial organization is required

Test Phase

- Functional Assessment: Quantify target outputs (product formation, substrate degradation) using analytical methods (HPLC, GC-MS, spectrophotometry)

- Community Dynamics: Monitor population ratios and stability through flow cytometry, sequencing, or microscopy

- Interaction Validation: Verify predicted ecological interactions through spent media experiments, co-culture studies, and omics analyses

- Environmental Robustness: Evaluate performance under different physicochemical conditions (pH, temperature, substrate variations)

Learn Phase

- Data Integration: Combine multi-omics data (metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) with functional measurements

- Model Refinement: Update computational models with experimental data to improve predictive power

- Design Optimization: Identify bottlenecks and suboptimal interactions for correction in subsequent DBTL cycles

- Knowledge Extraction: Derive generalizable principles for future consortia design

Protocol: Synthetic Microbial Consortium for Distributed Bioproduction

This protocol details the creation of a two-member consortium for efficient bioproduction, demonstrating division of labor with reduced metabolic burden compared to a single chassis approach [2].

Materials

- Strain A: Specialized in precursor production (e.g., E. coli with enhanced precursor pathway)

- Strain B: Specialized in final biotransformation (e.g., E. coli with product synthesis pathway)

- Appropriate selective media for each strain

- Co-culture media supporting both strains

- Microfermenters or multi-well plates

- Analytical equipment for product quantification (HPLC, GC-MS)

Methodology

- Individual Strain Optimization

- Engineer each strain with necessary genetic modifications for specialized function

- Optimize growth conditions for each strain individually

- Characterize growth kinetics and metabolic profiles in monoculture

Communication System Implementation

- Implement unidirectional or bidirectional quorum sensing systems if coordinated gene expression is required

- Validate signal production and response in individual strains

- Characterize response curves for quorum sensing circuits

Consortium Assembly and Optimization

- Inoculate strains at varying ratios (1:1, 1:10, 10:1) in co-culture media

- Monitor population dynamics over 24-72 hours using selective plating or fluorescent markers

- Measure target compound production at regular intervals

- Identify optimal inoculation ratio that maximizes function while maintaining stability

Long-Term Stability Assessment

- Perform serial passaging (1:100 dilution every 24 hours) for 10-15 cycles

- Monitor population composition and functional output at each passage

- Isolate strains from endpoint community and re-sequence to identify evolutionary adaptations

Scale-Up Evaluation

- Transfer optimized consortium to bioreactor conditions

- Evaluate performance under controlled pH, dissolved oxygen, and feeding regimes

- Compare productivity to engineered monoculture controls

Troubleshooting

- If population imbalance occurs: Implement negative feedback circuits or trophic dependencies

- If productivity declines: Add metabolic controls or adjust cultivation parameters

- If contamination occurs: Introduce antibiotic markers with corresponding resistance genes

Signaling Pathways in Engineered Microbial Consortia

Cell-cell communication is fundamental for coordinating behavior in engineered microbial consortia. The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways implemented in synthetic communities.

Diagram 1: Bacterial Quorum Sensing Pathway

Diagram 2: Synthetic Consortium with Bidirectional Communication

Research Reagent Solutions for Community-Level Engineering

The successful implementation of CLE requires specialized reagents and tools designed for constructing, monitoring, and controlling multi-strain systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Community-Level Engineering

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Quorum Sensing Systems | Enable programmed cell-cell communication | Population synchronization; coordinated pathway activation |

| Orthogonal Metabolic Switches | Control inter-strain dependencies | Trophic coupling; population balance regulation |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Visualize population dynamics and spatial organization | Real-time monitoring of community composition |

| Metabolic Modeling Software | Predict community metabolic fluxes and interactions | Consortium design optimization; bottleneck identification |

| Selective Media Formulations | Maintain desired community composition | Selective enrichment of functional community members |

| Microfluidic Cultivation Devices | Create spatially structured communities | Study of spatial organization effects on community function |

| CRISPRi/a Systems | Regulate gene expression across communities | Dynamic pathway control without genetic modification |

| Stable Co-culture Media | Support multiple species without favoring one | Maintenance of community diversity and function |

These specialized reagents address the unique challenges of working with multi-strain systems, particularly in maintaining community stability, monitoring population dynamics, and implementing controlled interactions between community members. The development of orthogonal communication systems that do not cross-talk with native microbial signaling pathways is particularly valuable for creating predictable consortia [2].

Applications and Future Perspectives

CLE approaches are being applied across multiple biotechnology sectors, leveraging the unique capabilities of microbial consortia. In bioremediation, consortia can perform complex degradation pathways for persistent pollutants like hydrocarbons, pharmaceuticals, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that exceed the metabolic capabilities of individual strains [4]. In bioproduction, distributed metabolic pathways enable more efficient conversion of complex feedstocks to valuable compounds including biofuels, bioplastics, and pharmaceuticals [2]. Agriculture benefits from engineered microbial communities that enhance nutrient availability, promote plant growth, and provide pathogen protection through complex community interactions that mimic natural rhizosphere communities [3].

The future advancement of CLE will depend on improved computational tools for predicting community dynamics, high-throughput methods for constructing and screening consortia, and standardized parts for reliable inter-strain communication [3]. Integration with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence for community design and microfluidics for spatial control will further expand the capabilities of engineered microbial communities [4]. As the field matures, CLE is positioned to become a foundational biotechnology platform for developing sustainable solutions to challenges in manufacturing, environmental management, and healthcare.

Application Notes: Theoretical Foundations and Quantitative Data

Core Ecological Interaction Theories for Community Engineering

The rational design of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) is guided by key ecological principles that govern community stability and function. Understanding these interactions is critical for engineering robust systems for biotechnology applications [5].

Table 1: Ecological Interaction Types in Microbial Community Design

| Interaction Type | Functional Role in Community | Impact on Community Stability | Biotechnological Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Cross-feeding of metabolic byproducts enhances overall efficiency and resilience [5]. | Increases functional robustness and long-term coexistence [5]. | Division of labor in complex biosynthesis pathways [6]. |

| Commensalism | One member benefits while the other is unaffected; common under extreme conditions [5]. | Aids in environmental adaptation and community assembly. | Biofilm formation, habitat modification for other strains. |

| Competition | Driven by struggle for limited nutrients (e.g., nutrients, space) [5]. | Can destabilize communities if unchecked; can be harnessed to prevent invasion [5]. | Control of community composition, exclusion of pathogens. |

| Antagonism/Amensalism | Chemical warfare via antimicrobial compounds (e.g., antibiotics, bacteriocins) [5]. | Suppresses competitors; outcomes predicted by phylogeny and biosynthetic gene clusters [5]. | Biological control of pathogens, shaping population dynamics. |

| Syntrophy | Metabolic cooperation for degrading recalcitrant compounds; one's waste is another's substrate. | Creates obligate dependencies that strongly stabilize the consortium. | Bioremediation of pollutants, anaerobic digestion. |

Microbial Helper Theory presents a framework where certain microbes, termed "helpers," support the survival or function of "beneficiary" microbes by providing essential nutrients or mitigating stress [7]. This is pivotal in indirect pathogen control strategies, where targeting "helper" bacteria that support a pathogen can be more effective than direct confrontation [7].

Community Stability is a multi-dimensional target for design, encompassing:

- Resistance: The ability to withstand disturbance without significant functional or compositional shifts.

- Resilience: The capacity to recover from perturbation.

- Robustness: The ability to maintain structural organization and functional performance amid disturbances [5].

A critical challenge in community engineering is cheating behavior, where some members exploit shared resources without contributing, potentially leading to the collapse of mutualistic partnerships [5]. Mitigation strategies include incorporating spatial organization to alter quorum sensing dynamics and public goods distribution [5].

Quantitative Data and Design Principles

Table 2: Stability Optimization and Functional Design Parameters for SynComs

| Design Parameter | Target Metric/Consideration | Experimental Validation Method | Reference/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity-Functionality Trade-off | Balance high ecological performance with scalability; over-simplified consortia risk losing keystone species [5]. | Multi-omics analysis (16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomics) [5] [7]. | High-diversity SynComs improve performance but hinder scalability [5]. |

| Spatial Structuring | Implement to promote division of labor, communication, and suppress cheating [5]. | Confocal microscopy, microfluidics. | Alters QS dynamics and public goods distribution [5]. |

| Keystone Species Selection | Identification via genomic screening for hub taxa in interaction networks [5]. | Correlation network analysis (e.g., CoNet, SparCC) [5] [7]. | "Hub" taxa disproportionately influence community structure [5]. |

| Indirect Pathogen Inhibition | Target Pathogen Helper (PH) bacteria instead of the pathogen itself [7]. | Co-culture infection models (e.g., in skin, rhizosphere) [7]. | Suppressing PH with inhibitor (IPH) improved outcomes vs. direct inhibition [7]. |

| Market Size & Investment | Synthetic biology sector investment: US\$16.35B (2023); Market forecast: ~US\$148B by 2033 [4]. | N/A | Combined private and public investment [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DBTL Cycle for Rational SynCom Assembly

This protocol outlines an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) framework for constructing stable and functional Synthetic Microbial Communities [5].

I. Design Phase: Computational Prediction of Interaction Networks

- Strain Selection: Curate a candidate strain library based on genomic data (e.g., presence of specific metabolic pathways, antibiotic resistance genes, known interactions).

- Network Modeling: Use computational tools (e.g., CoNet, SparCC, SPIEC-EASI) to infer microbial association networks from abundance data [5] [7].

- Metabolic Modeling: Employ Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) to predict cross-feeding opportunities, resource competition, and potential for division of labor [5].

- Interaction Scoring: Score and select strain combinations that maximize desired positive interactions (mutualism, commensalism) and minimize destabilizing negative interactions (e.g., unchecked competition).

II. Build Phase: Assembly of Defined Microbial Consortia

- Strain Cultivation: Individually culture each selected strain in its optimal medium to mid-logarithmic growth phase.

- Standardized Inoculation: Harvest cells, wash, and resuspend in a defined, common medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium). Use optical density (OD600) or cell counting to standardize the initial inoculum for each strain.

- Consortium Assembly: Combine strains in the desired initial ratios and total biomass in the chosen cultivation system (e.g., shaken flask, bioreactor, microfluidic device).

III. Test Phase: Functional Validation under Target Conditions

- Longitudinal Sampling: Sample the consortium repeatedly over time (e.g., over 48-120 hours).

- Compositional Analysis:

- DNA Extraction: Perform on all samples.

- qPCR or 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Quantify the absolute or relative abundance of each strain to track population dynamics and assess compositional stability [5].

- Functional Analysis:

- Metabolite Analysis: Use HPLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS to quantify the consumption of substrates and production of target metabolites or byproducts.

- Activity Assays: Perform enzyme activity assays or reporter system measurements for the function of interest (e.g., pollutant degradation, antibiotic production).

IV. Learn Phase: Data-Driven Model Refinement

- Data Integration: Correlate compositional data (from 16S sequencing) with functional output data (metabolite concentrations).

- Model Calibration: Use the experimental data to refine and calibrate the initial computational models, improving their predictive power for the next DBTL cycle.

- Hypothesis Generation: Identify unsuccessful interactions or instability triggers and generate new hypotheses for community re-design.

Protocol 2: Indirect Inhibition of Pathogens via Helper Suppression

This protocol details a method to control pathogens by targeting their supporting "helper" microbes, based on research in skin and plant systems [7].

I. Identification of Pathogen Helper (PH) and Inhibitor (IPH) Bacteria

- Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples from the niche of interest (e.g., rhizosphere soil, human skin swab).

- Co-culture Screening: a. Co-culture the pathogen with individual isolates from the sample collection. b. Measure pathogen growth (e.g., by CFU counting, OD600) and/or virulence factor expression. c. Identify Pathogen Helper (PH) strains that significantly enhance pathogen growth or virulence.

- Antagonism Screening: a. Screen the isolate collection for strains that inhibit the growth of the identified PH. b. Use a standard antagonism assay (e.g., cross-streak, agar diffusion). c. Identify Inhibitor of Pathogen Helper (IPH) strains.

II. Validation of Indirect Inhibition Efficacy

- In Vitro Consortium Setup:

- Group 1 (Control): Pathogen (P) alone.

- Group 2 (Helper Boost): P + PH.

- Group 3 (Direct Inhibition): P + Pathogen Inhibitor (PI).

- Group 4 (Indirect Inhibition): P + PH + IPH.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate all groups and measure:

- Pathogen population density (CFU/mL).

- Expression of key pathogen virulence genes (via RT-qPCR).

- In vitro virulence activity (e.g., biofilm formation, toxin production).

- In Vivo / In Situ Validation:

- Apply the same group formulations to a relevant host model (e.g., tomato plant for phytopathogens, mouse model for skin pathogens) [7].

- Measure disease severity, host inflammation markers, and pathogen load in the target tissue.

- Compare the efficacy of indirect inhibition (Group 4) against direct inhibition (Group 3).

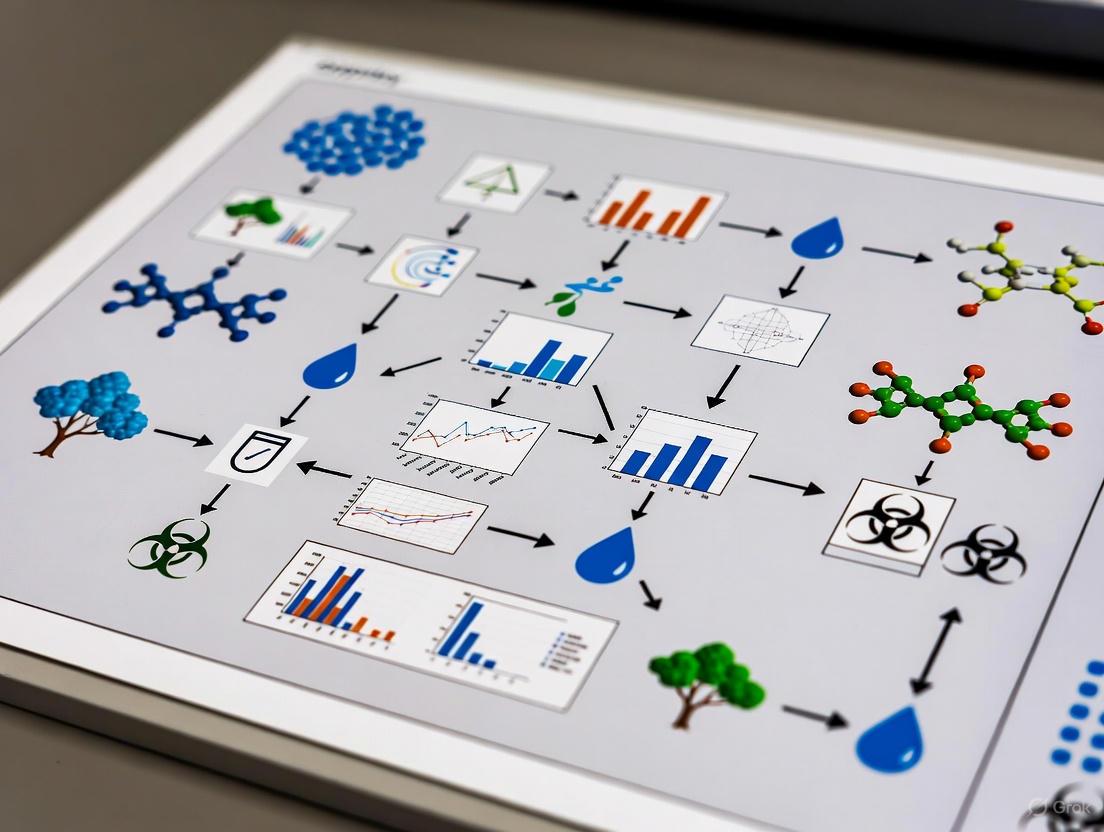

Mandatory Visualizations

Microbial Interaction Network

DBTL Cycle for SynComs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Application | Specific Use-Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| CoNet / SparCC / SPIEC-EASI | Inference of microbial association networks from abundance data [5] [7]. | Predicting mutualistic or competitive pairs during the Design phase of SynCom construction. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Predictive modeling of metabolic interactions, including cross-feeding and resource competition [5]. | Designing a consortium for efficient lignocellulose degradation by dividing metabolic tasks [6]. |

| Synthetic Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) | Chemical inducers for quorum sensing-mediated communication in engineered Gram-negative consortia [6]. | Synchronizing population density-dependent behaviors like biofilm formation or enzyme production. |

| Phenyl Lactic Acid | Metabolite produced by IPH bacteria that inhibits specific Pathogen Helper bacteria [7]. | Indirect control of S. aureus by suppressing its helper, C. acnes, in skin microbiome studies. |

| Defined Minimal Media (e.g., M9) | Cultivation medium with precisely known components for studying metabolic interactions without complex nutrient interference. | Tracking cross-feeding of specific amino acids or carbon sources between mutualistic partners. |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Reagents | Profiling taxonomic composition and tracking population dynamics in a consortium over time [5] [7]. | Monitoring the stability of a 5-strain SynCom during a 4-week longitudinal experiment. |

| 2-Acetoxy-3-deacetoxycaesaldekarin E | 2-Acetoxy-3-deacetoxycaesaldekarin E, MF:C24H30O6, MW:414.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyrocatechol monoglucoside | High-Purity (2R,3S,4S,5R)-2-(hydroxymethyl)-6-(2-hydroxyphenoxy)oxane-3,4,5-triol | Explore the research applications of (2R,3S,4S,5R)-2-(hydroxymethyl)-6-(2-hydroxyphenoxy)oxane-3,4,5-triol. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for personal use. |

Overcoming the Limitations of Single-Strain Engineering with Consortia

Implementing complex genetic circuits or lengthy metabolic pathways in a single microbial host often leads to significant challenges, including metabolic burden, redox imbalance, and the emergence of loss-of-function mutants [8]. These limitations can result in poor product yields, reduced host fitness, and unpredictable system performance. Engineering microbial consortia presents a powerful alternative by distributing these tasks across multiple, specialized populations [9]. This strategy, inspired by natural microbial communities, allows for a division of labor, where each strain is optimized for a specific sub-function, thereby reducing the individual burden and enhancing the overall stability and productivity of the system [10].

The fundamental principle behind using consortia is to overcome competitive exclusion, an ecological concept stating that two species competing for the same niche cannot stably coexist [8]. By designing stabilizing interactions such as amensalism, mutualism, or programmed population control, synthetic biologists can create tunable and robust multi-strain systems for sophisticated biotechnological applications [8] [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for sustainable bioprocesses, including bioremediation, therapeutic applications, and the production of high-value chemicals [8] [10].

Key Strategies for Designing Stable Consortia

A primary challenge in consortium engineering is ensuring the stable coexistence of multiple populations. In the absence of stabilizing mechanisms, faster-growing strains will inevitably outcompete and eliminate slower-growing partners [9]. Several key strategies have been developed to address this:

Amensalism via Bacteriocin-Mediated Killing

This approach involves engineering a strain to produce a bacteriocin—a secreted antimicrobial peptide—that targets a competitor strain [8]. This one-sided inhibitory interaction, known as amensalism, allows the killer strain to regulate the population of the target strain. The system can be made tunable by placing the bacteriocin gene under the control of a quorum-sensing (QS) circuit, enabling population-density-dependent regulation [8]. This mechanism effectively flips the competitive advantage, allowing a slower-growing but armed strain to persist in a co-culture with a faster-growing competitor.

Programmed Population Control

Another method to mitigate competitive exclusion is to implement negative feedback loops that limit the growth of each population [9]. For example, synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) can be used where each strain is engineered to lyse upon reaching a high cell density, which is communicated via QS molecules [9]. This self-limitation prevents any single population from overgrowing and dominating the culture, thus enabling stable coexistence.

Mutualistic Interactions

Mutualism, where both strains derive a benefit from each other, can also stabilize a consortium. This has been successfully used in metabolic engineering, where one strain consumes a waste product (e.g., acetate) produced by the other, thereby detoxifying the shared environment and enabling robust co-culture [9] [10]. Such cross-feeding interactions create interdependencies that maintain community composition.

Table 1: Ecological Interaction Strategies for Consortium Stabilization

| Interaction Type | Mechanism | Effect on Stability | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amensalism | One strain secretes a toxin (e.g., bacteriocin) that kills a competitor [8]. | Prevents competitive exclusion of slower-growing, engineered strain. | Population control in E. coli co-cultures [8]. |

| Programmed Negative Feedback | Strains are engineered to self-lyse via a QS-controlled circuit at high density [9]. | Creates self-limiting populations, allowing for coexistence. | Stable two-strain consortia using synchronized lysis circuits [9]. |

| Mutualism | Strains exchange essential nutrients or remove mutual growth inhibitors [9] [10]. | Creates interdependencies that maintain community composition. | Co-culture of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for taxane production [9]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Bacteriocin-Mediated Tunable Consortium

This protocol details the creation of a stable two-strain consortium using a bacteriocin-producing strain to control the population of a competitor strain [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Bacteriocin-Mediated Control

| Reagent / Strain | Function / Genotype | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Bacteriocin Producer | E. coli JW3910 with plasmid for microcin-V expression and mCherry [8]. | Constitutively expresses fluorescent protein; bacteriocin expression can be inducible (e.g., via 3OC6-HSL). |

| Competitor Strain | E. coli MG1655 [8]. | Faster-growing, susceptible to the bacteriocin. |

| N-3-oxohexanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL) | Exogenous inducer molecule [8]. | Used to repress or tune the bacteriocin production rate in the engineered strain. |

| LB Medium | Standard lysogeny broth [8]. | Growth medium for co-culture. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core logic and workflow for setting up and analyzing the bacteriocin-mediated consortium:

- Strain Preparation: Inoculate separate overnight cultures of the engineered bacteriocin-producing strain (e.g., E. coli JW3910 with microcin-V and mCherry plasmids) and the competitor strain (E. coli MG1655) [8].

- Co-culture Inoculation: Mix the two strains in fresh LB medium at a defined initial ratio (e.g., 1:1). Use a range of initial optical densities (OD) (e.g., from 0.001 to 0.1) to emulate different dilution rates and resource availability [8].

- Induction and Monitoring:

- Add different concentrations of the inducer 3OC6-HSL (e.g., 0 nM to 100 nM) to the co-cultures to repress bacteriocin production [8].

- Incubate the co-cultures with shaking at 37°C.

- Monitor the population dynamics in real-time using a plate reader that tracks optical density (total biomass) and mCherry fluorescence (engineered strain population) [8].

- Population Analysis: At a key time point (e.g., after 5 hours of growth, during late exponential phase), take samples for colony-forming unit (CFU) counts on selective plates to determine the absolute abundance of each strain.

- Data Interpretation: The consortium is considered stable if both populations persist over multiple growth-dilution cycles. The final population ratio can be tuned by the initial density and the concentration of the exogenous inducer.

Protocol 2: Division of Labor for Complex Metabolite Production

This protocol describes the use of a two-species consortium to compartmentalize and optimize a long biosynthetic pathway, reducing metabolic burden and leveraging host-specific advantages [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Division of Labor

| Reagent / Strain | Function / Genotype | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Upstream Pathway Strain | Engineered E. coli for high-level production of a pathway intermediate (e.g., taxadiene) [10]. | Optimized for high-flux, initial steps of the pathway. |

| Downstream Pathway Strain | Engineered S. cerevisiae for functional expression of cytochrome P450s for oxygenation [10]. | Specialized host for expressing difficult enzymes like P450s; consumes intermediate. |

| Specialized Growth Medium | Medium supporting both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (e.g., defined medium with necessary nutrients) [10]. | Must allow for the growth and function of both species. |

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the modular workflow for a divided metabolic pathway:

- Modular Pathway Optimization:

- Independently engineer and optimize the upstream module (e.g., genes for taxadiene production) in E. coli and the downstream module (e.g., P450 genes for oxygenation) in S. cerevisiae [10].

- Confirm that the intermediate (e.g., taxadiene) is secreted by the upstream strain and can be taken up by the downstream strain.

- Consortium Cultivation:

- Inoculate the upstream E. coli strain in a suitable medium and allow it to grow to mid-exponential phase.

- Inoculate the downstream S. cerevisiae strain either simultaneously or after a delay, depending on the production kinetics of the intermediate [10].

- Test different initial inoculation ratios (e.g., 8:2, 5:5, 2:8 for upstream:downstream) to find the optimal population balance for maximum product titer [10].

- Process Monitoring and Harvest:

- Monitor cell density of both populations using species-specific markers or plating.

- Sample the culture broth periodically to measure intermediate and final product concentrations using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Harvest the culture when the product titer reaches its maximum.

Quantitative Data and Analysis

The performance of engineered consortia can be quantified by tracking population dynamics and product output under different conditions.

Table 4: Quantitative Analysis of a Bacteriocin-Stabilized Consortium [8]

| Initial OD | [3OC6-HSL] (nM) | Time to Engineered Strain Dominance (h) | Competitor Strain Reduction at 5h | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | 0 | >20 | <10% | Low density, low bacteriocin: Competitor dominates. |

| 0.01 | 0 | ~10 | ~50% | Intermediate state. |

| 0.1 | 0 | ~5 | >90% | High density, high bacteriocin: Engineered strain dominates. |

| 0.1 | 10 | ~15 | ~30% | Inducer represses bacteriocin, relieving killing. |

| 0.1 | 100 | >20 | <10% | Strong repression: Competitor dominates. |

Table 5: Performance of a Divided Metabolic Pathway for Taxane Production [10]

| Cultivation Method | Strain(s) | Final Product Titer (mg/L) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Strain | S. cerevisiae (full pathway) | Low | Baseline; full pathway is burdensome. |

| Co-culture | E. coli (upstream) + S. cerevisiae (downstream) | 33 mg/L | Division of labor: Each host performs its specialized function optimally. |

| Co-culture (Optimized Ratio) | E. coli + S. cerevisiae (tuned ratio) | >33 mg/L | Tunability: Population ratio can be optimized to maximize flux to the product. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 6: Key Reagents and Tools for Consortium Engineering

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in Consortium Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Genetic Parts | Enable cell-cell communication for coordinated gene expression and population control (e.g., LuxR/LuxI, LasR/LasI) [9]. |

| Bacteriocins / Toxins | Effector Molecules | Used to create amensal interactions and control population dynamics (e.g., microcin-V) [8]. |

| Orthogonal Inducer Molecules | Chemical Regulators | Provide external control over gene circuits without crosstalk (e.g., aTc, IPTG, 3OC6-HSL) [8]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins | Reporter Proteins | Allow for real-time, non-destructive monitoring of individual population densities in a co-culture [8]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational Tools | Enable in silico prediction of metabolic interactions and optimization of consortium composition for desired output [11]. |

| 20S,24R-Epoxydammar-12,25-diol-3-one | 20S,24R-Epoxydammar-12,25-diol-3-one|Research Compound | Explore 20S,24R-Epoxydammar-12,25-diol-3-one for diabetes and cancer research. This natural dammarane triterpenoid is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Beclomethasone 17-Propionate-d5 | Beclomethasone 17-Propionate-d5, MF:C25H33ClO6, MW:470.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineered microbial consortia represent a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving beyond the constraints of single-strain engineering. By strategically employing ecological principles such as amensalism and mutualism, and implementing control strategies like programmed population regulation, researchers can create robust, tunable, and complex multi-strain systems. The protocols and data outlined herein provide a framework for leveraging division of labor to achieve enhanced bioproduction, advanced biosensing, and the sustainable application of biotechnology. As the field progresses, the integration of computational modeling and high-throughput assembly of communities will further accelerate the design and deployment of these sophisticated systems for a wide range of industrial and therapeutic applications [11].

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Design Approaches for Community Assembly

In the pursuit of sustainable biotechnological applications, engineering microbial consortia has emerged as a powerful paradigm for converting waste into valuable resources [12]. The assembly of these complex communities can be orchestrated through two principal design philosophies: the top-down and bottom-up approaches. The top-down approach involves applying selective pressures to steer the structure and function of a native microbial community, whereas the bottom-up approach focuses on the rational design and assembly of a new consortium from isolated or engineered members [12]. Understanding the principles, applications, and methodologies of these strategies is crucial for advancing community-level engineering in bioremediation, biomanufacturing, and therapeutic development. This article provides a detailed comparison of these approaches and outlines standardized protocols for their implementation.

Comparative Analysis: Core Principles and Applications

The distinction between top-down and bottom-up design extends across multiple disciplines, from ecology to software engineering, but the core principles remain consistent. The following table summarizes their fundamental characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of top-down and bottom-up approaches.

| Feature | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Breakdown of a complex system into smaller, manageable subsystems [13] [14]. | Piecing together smaller systems to give rise to a more complex, emergent system [13] [14]. |

| Design Sequence | From the overall system overview to detailed components [13] [15]. | From individual base elements to the complete top-level system [13] [15]. |

| Primary Control Mechanism | Selective environmental pressure (e.g., pH, temperature, substrate) [12]. | Rational design based on known metabolic pathways and interactions [12]. |

| Typical Redundancy | Can be higher, as parts are programmed separately [13]. | Minimized through data encapsulation and reusability of components [13]. |

| Ideal Application Context | Structured programming; steering natural consortia in bioprocesses like anaerobic digestion [12] [13]. | Object-Oriented Programming; constructing synthetic microbial consortia for targeted bioproduction [12] [13]. |

In ecology and biotechnology, these approaches manifest in specific ways for community assembly. A top-down approach uses operating conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, feeding cycles) as a selective pressure to guide an existing, complex microbial consortium toward a desired function, such as enhancing biomethane production in anaerobic digesters [12]. In contrast, a bottom-up approach leverages prior knowledge of microbial metabolism to rationally assemble a synthetic consortium from scratch, offering greater control for producing specific biochemicals [12].

The choice of approach can also be dynamic. Research on marine biofilms has demonstrated that ecological drivers can switch from bottom-up to top-down control during community succession. Early assembly was primarily driven by bottom-up substrate properties, but as the community matured, top-down control by predators became progressively more important in shaping the composition [16] [17].

Table 2: Applications of top-down and bottom-up approaches in microbiome engineering for biotechnology.

| Aspect | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Action | Decomposition of the system occurs [13]. | Composition of the system happens [13]. |

| Representative Bioprocess | Anaerobic Digestion (AD) for biogas production [12]. | Synthetic Consortia for medium-chain carboxylic acid (MCCA) production [12]. |

| Key Challenge | Disentangling complex microbial interactions; low resolution of control [12]. | Ensuring long-term stability of the defined consortium; optimal assembly [12]. |

| Level of Control | Coarse-grained, community-level control [12]. | Fine-grained, species-level control [12]. |

| Explainable Variance | Can be limited; other factors (e.g., top-down predation) may account for significant variance [16]. | High for designed interactions, but emergent interactions may be unpredictable. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Top-Down Community Steerage

This protocol outlines the process of steering a native microbial community derived from activated sludge to enhance the production of medium-chain carboxylic acids (MCCAs) through specific environmental pressures.

1. Principle: To manipulate operational parameters in a bioreactor to apply selective pressure, enriching for a microbial community with a desired metabolic function—in this case, chain elongation for MCCA production [12].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Inoculum: Anaerobic granular sludge or complex municipal/industrial wastewater.

- Substrate: Complex organic waste stream (e.g., food waste, lignocellulosic hydrolysate).

- Bioreactor: Fermenter system with pH, temperature, and gas flow control.

- Anaerobic Chamber: For sample manipulation under oxygen-free conditions.

- Analytical Instruments: HPLC for carboxylic acid analysis, GC for gas analysis, DNA sequencer for community analysis.

3. Procedure: 1. Inoculum Preparation: Collect anaerobic sludge and homogenize it under anaerobic conditions to create a consistent starting community. 2. Bioreactor Setup & Operation: * Fill the bioreactor with inoculum and growth medium containing the complex substrate. * Set the initial pH to 5.5 using a controlled acid/base pump to select for acid-tolerant chain-elongating bacteria [12]. * Maintain a mesophilic temperature of 35°C. * Set a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 4-5 days and a solid retention time (SRT) of 15 days to selectively retain slower-growing microbes. 3. Monitoring: Regularly monitor pH, temperature, and gas production. Take liquid samples for HPLC analysis of SCCAs and MCCAs, and for DNA extraction. 4. Community Analysis: Perform 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing on samples from different time points. Use bioinformatic tools to track shifts in microbial composition (e.g., enrichment of Clostridium and Megasphaera). 5. Iterative Refinement: Based on performance data (MCCA yield) and community analysis, adjust parameters like pH or HRT to further steer the community toward the target function.

Protocol for Bottom-Up Community Assembly

This protocol describes the rational design and assembly of a synthetic microbial consortium for the production of a target compound, such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), from a defined substrate like glycerol [12].

1. Principle: To construct a defined consortium by selecting microorganisms with complementary metabolic pathways that work synergistically to convert a substrate into a desired product [12].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Strains: Pure cultures of selected microorganisms (e.g., Pseudomonas putida for PHA production, and a companion species for substrate pre-processing).

- Growth Media: Defined mineral media suitable for all consortium members.

- Bioreactor: CSTR or batch system with precise monitoring.

- Optical Density (OD) Spectrophotometer

- Flow Cytometer for tracking individual population dynamics.

- HPLC System for substrate and product quantification.

3. Procedure: 1. Consortium Design: * Pathway Identification: Define the metabolic pathway from substrate (glycerol) to product (PHA). Identify key steps and potential bottlenecks. * Strain Selection: Select two or more microbial strains whose combined metabolism covers the entire pathway. For example, one strain may convert glycerol to precursors, while another (e.g., P. putida) converts precursors to PHA. * Interaction Analysis: Use genomic data and literature to predict potential synergistic (e.g., cross-feeding) or competitive interactions. 2. Individual Strain Characterization: * Cultivate each strain in isolation to determine its growth kinetics, substrate consumption profile, and product formation under the intended bioreactor conditions. 3. Consortium Assembly & Cultivation: * Inoculate the bioreactor containing defined media with the pre-cultured strains at a predetermined initial ratio (e.g., 1:1 cell count). * Maintain controlled environmental conditions (pH 7.0, 30°C, sufficient aeration). 4. Performance Monitoring: * Track consortium performance by measuring OD, substrate concentration (HPLC), and PHA yield. * Use flow cytometry (if using fluorescently tagged strains) or qPCR with strain-specific primers to monitor the abundance and stability of each population over time. 5. Optimization: Adjust initial inoculation ratios, media composition, or feeding strategies based on performance and population data to improve product yield and consortium stability.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical flow and key relationships of the two design approaches.

Diagram 1: Top-down community steerage workflow.

Diagram 2: Bottom-up community assembly workflow.

Diagram 3: A hybrid 'middle-out' design strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the featured experiments for community assembly and analysis.

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for community assembly studies.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Waste Stream | Serves as a renewable feedstock and selective pressure in top-down approaches [12]. | Food waste or lignocellulosic biomass used in anaerobic digestion to produce biogas [12]. |

| Defined Mineral Media | Provides essential nutrients without undefined components, crucial for bottom-up consortia [12]. | Supporting the growth of a synthetic PHA-producing consortium in a controlled bioreactor environment [12]. |

| 16S/18S rRNA Primers | Allows for amplification and sequencing of prokaryotic and eukaryotic marker genes for community analysis [16]. | Tracking shifts in microbial composition in response to pH manipulation in a top-down experiment [16]. |

| 100 µm Mesh Enclosure | Excludes large predators to experimentally test the effects of top-down control on community assembly [16]. | Studying the impact of predator exclusion on the succession of marine biofilm communities [16]. |

| 13-O-Deacetyltaxumairol Z | 13-O-Deacetyltaxumairol Z, MF:C31H40O12, MW:604.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Monononyl Phthalate-d4 | Monononyl Phthalate-d4, MF:C₁₇H₂₀D₄O₄, MW:296.39 | Chemical Reagent |

The engineering of microbial communities represents a frontier in synthetic biology for developing sustainable biotechnological applications. Central to this endeavor are three interconnected principles: division of labour, modularity, and robustness. Division of labour, where specialized subpopulations or modules perform distinct tasks, enables complex functions that are difficult or impossible for single strains [18] [6]. This specialization is structured through modularity—the organization of systems into discrete, interconnected units which facilitates independent evolution, enhances robustness, and improves information flows [19] [20]. Robustness, the system's capacity to maintain function despite perturbations, is a critical emergent property that determines the stability and industrial viability of engineered communities [20] [21]. This framework provides the foundation for engineering microbial consortia with enhanced capabilities for pharmaceutical production, bioremediation, and sustainable bioprocessing [1] [6] [22].

Key Theoretical Framework

Evolutionary and Ecological Foundations

Division of labour evolves under specific conditions. Theoretical models indicate it is favoured by: (1) positional effects where module location predisposes specific functions; (2) accelerating performance functions where specialized effort yields disproportionate returns; and (3) synergistic interactions between modules [18]. Conversely, selection for functional robustness can counteract specialization when modules are prone to damage or loss [18].

Spatial structure significantly influences this evolution. In topologically constrained groups (e.g., filaments or branching structures), division of labour can evolve even with diminishing returns from specialization, as local interactions create efficiency benefits at the group level [21]. This contrasts with unstructured groups where accelerating returns are typically essential [21].

Modularity in Biological Systems

Modularity occurs at multiple biological scales, from gene regulatory networks to microbial consortia. In Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), modular structures constrain phenotypic effects of mutations within specific modules, facilitating adaptation without disrupting established functions [20]. This compartmentalization enables independent optimization of different modules and enhances evolvability [19] [20].

The relationship between modularity and robustness is particularly relevant for engineering. Studies of GRNs demonstrate that modularity and robustness are positively correlated; modular structures enhance a system's ability to withstand perturbations while maintaining function [20].

Table 1: Key Concepts and Their Functional Roles in Engineered Communities

| Concept | Functional Role | Engineering Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Division of Labour | Task specialization between subpopulations [18] [6] | Enables complex, multifunctional processes [6] |

| Modularity | Organization into discrete functional units [19] | Allows independent optimization of modules [19] [20] |

| Robustness | Maintenance of function under perturbation [20] | Enhances industrial stability and reliability [1] [6] |

Quantitative Metrics and Analysis

Engineering microbial consortia requires quantitative frameworks to assess system performance. The following metrics enable rigorous characterization of division of labour, modularity, and robustness.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Analyzing Engineered Microbial Consortia

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Application in Consortia |

|---|---|---|

| Division of Labour | Specialization index [18]; Task performance efficiency [21] | Quantifies functional specialization between strains |

| Modularity | Network modularity index (Q) [20]; Interaction density [19] | Measures degree of functional compartmentalization |

| Robustness | Homeostatic capacity [20]; Invasion resistance [6] | Assesses stability against perturbations |

| Performance | Product yield [1]; Biomass productivity [22] | Evaluates overall system functionality |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering Synthetic Microbial Consortia with Division of Labour

Objective: Construct a two-strain consortium where specialized strains cooperate for enhanced production of target compounds.

Background: Division of labour allows distribution of metabolic burden, overcoming limitations of single-strain engineering [1] [22]. This protocol utilizes Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli as model chassis.

Materials:

- Strains: S. cerevisiae BY4741, E. coli DH5α

- Vectors: Golden Gate cloning system compatible plasmids [22]

- Media: Minimal media with selected carbon sources

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC for product quantification, flow cytometer for population tracking

Methodology:

- Strain Design:

- Identify target pathway and divide into specialized modules

- Engineer producer strain with biosynthetic pathway genes

- Engineer helper strain with genes for precursor supply and co-factor regeneration [22]

Genetic Modification:

Consortium Assembly:

- Inoculate strains in co-culture with optimized initial ratios (typically 1:1 to 1:5 helper:producer)

- Monitor population dynamics via fluorescent markers for 72-96 hours

Validation:

- Quantify target compound production versus single-strain controls

- Assess stability over multiple serial passages

- Analyze metabolic cross-talk via transcriptomics

Troubleshooting:

- Competition Issues: Implement dependency mechanisms (e.g., auxotrophies)

- Population Drift: Use inducible kill switches or quorum sensing-based regulation

- Reduced Productivity: Optimize medium composition and cultivation conditions

Protocol 2: Assessing Robustness to Environmental Perturbations

Objective: Quantify consortium stability under variable industrial conditions.

Background: Robustness is essential for industrial application where environmental fluctuations occur [20] [6].

Materials:

- Established synthetic consortium

- Bioreactor systems with monitoring capability

- Stress inducers (temperature shifts, pH variation, osmotic stress)

Methodology:

- Perturbation Regimes:

- Apply abrupt temperature shifts (30°C to 37°C)

- Introduce pH fluctuations (6.8 to 7.5)

- Vary nutrient availability (carbon source switching)

Monitoring:

- Track population composition every 4 hours via flow cytometry

- Measure product titer every 12 hours

- Sample for transcriptomic analysis at peak perturbation

Analysis:

- Calculate resilience index (time to return to baseline production)

- Determine functional redundancy (correlation of function with composition changes)

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core conceptual frameworks and experimental workflows for engineering robust microbial consortia through division of labour and modular design.

Conceptual Framework of Core Principles

Experimental Workflow for Consortium Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Consortium Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning Systems | Golden Gate Assembly [22] | Modular genetic part assembly |

| Communication Modules | Acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) systems [6] | Enable inter-strain coordination |

| Selection Systems | Auxotrophic markers, Antibiotic resistance | Maintain population balance |

| Metabolic Tracers | 13C-labeled substrates | Track metabolite exchange |

| Population Tracking | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) | Monitor strain ratios dynamically |

| Inducible Systems | Tet-On, Arabinose-inducible | Control gene expression timing |

| Junipediol B 8-O-glucoside | Junipediol B 8-O-glucoside, CAS:188894-19-1, MF:C16H22O9, MW:358.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Epipterosin L 2'-O-glucoside | Epipterosin L 2'-O-glucoside, CAS:61117-89-3, MF:C21H30O9 | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Sustainable Biotechnology

Pharmaceutical Production

Engineering microbial consortia enables complex pharmaceutical production through pathway compartmentalization. For example, polyphenol synthesis can be divided between specialized strains: one producing precursors and another performing final modifications [22]. This division of labour reduces metabolic burden and increases titers compared to single-strain approaches.

Biofuel and Bioremediation Applications

Consortia demonstrate superior capabilities in lignocellulosic biofuel production. Specialist strains can separately process five- and six-carbon sugars, overcoming metabolic conflicts that limit single strains [6]. In bioremediation, division of labour allows simultaneous degradation of multiple contaminants through complementary metabolic pathways [1].

Advanced Bioprocessing

Electromicrobiology approaches enhance consortium functionality by using poised electrodes as electron donors/acceptors. This enables targeted stimulation of specific community members and pathways, allowing precise control of consortium function for bioproduction or bioremediation [1].

The integration of division of labour, modularity, and robustness provides a powerful framework for engineering microbial communities with enhanced biotechnological capabilities. By applying the protocols, metrics, and tools outlined in these application notes, researchers can design consortia with the stability and functionality required for industrial applications. This approach represents a paradigm shift from single-strain engineering to community-level engineering, offering new pathways for sustainable bioproduction and environmental applications.

Building and Deploying Microbial Consortia: From Lab to Field

Trait-Based Approaches for Rational Consortium Design

The burgeoning field of synthetic ecology is increasingly focused on designing microbial consortia to perform complex, sustained functions that are challenging for individual strains. Trait-based approaches are central to this endeavor, enabling the rational design of multi-species communities by selecting organisms with specific, complementary biochemical capabilities [23]. This methodology moves beyond taxonomy to focus on the functional roles of microorganisms, such as their metabolic pathways and interaction behaviors, which directly determine the consortium's collective output and stability [24]. Framing consortium design within this trait-based paradigm is crucial for advancing sustainable biotechnological applications, including bioremediation, the production of high-value chemicals, and sustainable energy solutions, as it provides a structured framework for optimizing community-level functions [23] [4] [25].

Core Principles and Key Traits for Design

Rational consortium design relies on partitioning complex metabolic tasks across different specialist members, thereby achieving a division of labor. This strategy can enhance overall productivity, improve substrate utilization, and increase the robustness of the biotechnological process [23] [6]. The stability and function of a synthetic consortium are governed by the interplay of key microbial traits.

Table 1: Key Functional Traits for Microbial Consortium Design

| Trait Category | Specific Trait Examples | Impact on Consortium Function |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Capabilities | Substrate utilization profile, waste product formation, biosynthesis of essential metabolites (e.g., amino acids, vitamins) [25]. | Determines nutrient cycling, cross-feeding opportunities, and division of labor. |

| Interaction Modalities | Metabolic cross-feeding (syntrophy) [25], quorum sensing [25] [6], production of antimicrobials [25]. | Governs population dynamics, structural stability, and collective behavior. |

| Stress Resistance | Tolerance to pH, temperature, oxidative stress, or specific inhibitors (e.g., heavy metals, solvents) [6]. | Enhances community resilience and functional stability in non-ideal or fluctuating environments. |

| Growth Parameters | Specific growth rate, yield, affinity for substrates [25]. | Influences relative population abundances and the long-term balance of the community. |

The selection of traits should be guided by the target application. For instance, a consortium designed for bioremediation might combine traits for the degradation of a complex pollutant across several species, while a consortium for chemical production would emphasize high-yield pathways partitioned to minimize metabolic burden [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing a trait-based approach, from initial design to functional validation.

Protocol 1: Trait-Based Consortium Design and Assembly

Objective: To rationally design and assemble a synthetic microbial consortium based on predefined functional traits.

Materials:

- Strain Collection: Pure cultures of candidate microbial strains.

- Culture Media: Defined minimal media and rich media (e.g., LB, YPD).

- Auxotrophy Validation Media: Minimal media lacking specific amino acids, vitamins, or other nutrients.

- Bioreactors or Multi-Well Plates: For culturing consortia.

- Spectrophotometer or Flow Cytometer: For monitoring microbial growth.

Methodology:

- Define Target Function: Clearly state the overarching function of the consortium (e.g., "Production of resveratrol from simple sugars" or "Degradation of cellulose to ethanol") [23].

- Deconstruct Function into Sub-tasks: Break down the target function into discrete, complementary metabolic tasks. For example, for bioethanol from cellulose: (i) cellulose hydrolysis, (ii) glucose fermentation, and (iii) pentose fermentation [23] [6].

- Identify and Source Strains: Select microbial strains that each perform one or more of the identified sub-tasks. Strains can be wild-type or genetically engineered [23] [25]. For example, Trichoderma reesei (cellulase secretion) can be paired with engineered E. coli (isobutanol production) [25].

- Validate Individual Traits in Isolation:

- Culture each strain individually in defined media to confirm its specific metabolic function (e.g., substrate consumption or product formation).

- For strains engineered for auxotrophy, confirm their inability to grow in minimal media without the required nutrient [25].

- Assemble the Consortium: Inoculate pre-cultured strains into a shared environment (e.g., a bioreactor) at a predetermined starting ratio (e.g., 1:1 for two members). Use a defined medium that supports the growth of all members, potentially through cross-feeding.

- Monitor Population Dynamics: Track the abundance of each member over time using methods like flow cytometry, quantitative PCR, or plating on selective media.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Community Function via Trait-Determining Genetic Features (TDGFs)

Objective: To quantitatively assess the functional performance of a consortium by measuring the expression of key genes responsible for critical traits, using metatranscriptomic data [24].

Materials:

- RNA Stabilization Solution (e.g., RNAlater).

- RNA Extraction Kit suitable for microbial communities.

- DNase I for DNA removal.

- Library Prep Kit for RNA-seq.

- High-Throughput Sequencer.

- Bioinformatics Workstation with software for transcriptome assembly (e.g., Trinity [24]) and abundance estimation (e.g., Kallisto [24]).

Methodology:

- Sample Collection and RNA Extraction:

- Collect samples from the consortium at relevant time points and immediately preserve them in RNA stabilization solution.

- Extract total RNA from the entire community, ensuring efficient lysis of all member species. Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Metatranscriptomic Sequencing:

- Deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from the total RNA to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA).

- Prepare a sequencing library from the enriched mRNA and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Assembly and Quantification: Assemble the quality-filtered sequencing reads into transcripts and estimate their abundance in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) [24].

- TDGF Identification: Identify contigs in the assembly that contain pre-defined Trait-Determining Genetic Features (TDGFs). These are genes encoding key enzymes for the function of interest (e.g., butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase for butyrate production or sulfatase for mucin decomposition) [24].

- Functional Abundance Calculation: Sum the TPM values of all contigs containing a specific TDGF. This cumulative TPM serves as a quantitative proxy for the functional group's activity within the community [24].

Table 2: Example Trait-Determining Genetic Features (TDGFs) for Functional Analysis

| Target Function | Functional Group | Example TDGF (Gene/Enzyme) | Role of TDGF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production | Butyrate Producers | Butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase | Catalyzes the final step in butyrate formation [24]. |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production | Acetogens | Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase / Acetyl-CoA synthetase | Key enzymes in the acetyl-CoA pathway for acetate production [24]. |

| Sulfate Reduction | Sulfate-Reducers | Dissimilatory sulfite reductase | Converts sulfite to hydrogen sulfide, the final step of sulfate reduction [24]. |

| Mucin Degradation | Mucin-Decomposers | Sulfatase / Alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase | Breaks down key covalent bonds in the mucin molecule [24]. |

Experimental Workflow and Metabolic Interactions

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for trait-based consortium design and a simplified view of the metabolic interactions that can be engineered.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Consortium Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Minimal Media | Provides a controlled environment to study nutrient exchange and auxotrophies; eliminates unknown variables from complex media [25]. | Cultivating syntrophic co-cultures to validate obligate mutualisms based on amino acid exchange. |

| Auxotrophic Strains | Genetically engineered strains that lack the ability to synthesize an essential metabolite, creating obligate metabolic dependencies [25]. | Building a stable two-member consortium where each partner cross-feeds an essential amino acid to the other. |

| Quorum Sensing Molecules | (e.g., acyl-homoserine lactones). Used to engineer programmable cell-cell communication and coordinate population-level behaviors [25] [6]. | Synchronizing the production of a toxic intermediate in one population with the expression of a degradation pathway in another. |

| RNA Stabilization Solution | (e.g., RNAlater). Preserves the in-situ transcriptional state of a microbial community instantly upon sampling, ensuring accurate metatranscriptomic data [24]. | Sampling a community for TDGF-based functional analysis to capture a snapshot of real-time activity. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Creates spatially structured environments for cultivating consortia, allowing metabolite exchange while restricting physical contact [25]. | Studying the effect of spatial organization on community stability and function, mimicking natural biofilms. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico reconstructions of microbial metabolism used with constraint-based modeling (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) to predict metabolic fluxes and interactions [11] [25]. | Predicting the optimal division of labor for a bioproduction pathway between two potential chassis organisms. |

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle in Microbiome Engineering

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework adopted from traditional engineering disciplines to advance microbiome engineering for sustainable biotechnological applications. This iterative process provides a structured methodology for harnessing microbial communities to address urgent societal and environmental challenges, ranging from bioremediation to sustainable biomanufacturing [3] [26]. The power of the DBTL framework lies in its iterative nature, where each cycle builds upon knowledge gained from previous iterations, progressively refining microbiome designs toward optimal performance [27]. As synthetic biology moves toward increasingly complex microbial systems, the DBTL cycle offers a rational approach to overcome the limitations of traditional trial-and-error methods, enabling both scientific discovery and translation into innovative solutions [3] [28].

Microbiome engineering applies two complementary design approaches within the DBTL framework: top-down design, which manipulates ecosystem-level controls to force ecological selection for desired functions, and bottom-up design, which focuses on engineering metabolic networks and microbial interactions from first principles [3] [29]. The DBTL cycle integrates these approaches through sequential phases that systematically bridge the gap between design concepts and functional microbial systems, making it particularly valuable for applications in medicine, agriculture, energy, and environmental sustainability [3] [26].

The DBTL Framework: Phase-by-Phase Analysis

Design Phase: Strategic Planning of Microbial Systems

The Design phase establishes the foundational blueprint for microbiome engineering initiatives. This critical first step involves developing preliminary model systems and establishing clear engineering goals before any physical construction begins [3]. Researchers employ both top-down and bottom-up design strategies during this phase, depending on system complexity and available knowledge of component interactions [29].

In top-down design, engineers conceptualize the system as an ecosystem model that captures inputs, outputs, physicochemical conditions, and known abiotic and biotic processes [3]. This approach uses carefully selected environmental variables—such as substrate loading rates, mean cell retention times, and redox conditions—to force ecological selection for desired metaphenotypes [3]. Mathematical modeling supports this process through mass balance analysis around chemicals and relevant microorganisms, simulating chemical and biochemical transformation rates using stoichiometric and kinetic parameters for key functional guilds [3].

In contrast, bottom-up design focuses on engineering the microbiome's metabolic network and microbial interactions from the molecular level upward [3]. This approach begins with obtaining genomes of individual community members, reconstructing their metabolic networks, and using modeling tools like flux balance analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic fluxes within and between populations [3]. Bottom-up design enables engineers to systematically evaluate the metabolic networks driving biological processes and ecological interactions, providing a computational framework for rationally designing microbiomes with specific properties such as distributed pathways, modular species interactions, and optimized ecosystem function [3].

Table 1: Key Elements of Microbiome Design Strategies

| Design Approach | Core Methodology | Applications | Tools and Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down Design | Manipulation of environmental variables to force ecological selection | Wastewater treatment, Bioremediation | Process-based models, Ecological engineering principles |

| Bottom-Up Design | Engineering metabolic networks and microbial interactions from molecular components | Synthetic microbial consortia, Metabolic engineering | Genome-scale metabolic models, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) |

Build Phase: Physical Construction of Engineered Microbiomes

The Build phase translates theoretical designs into physical, biological reality through hands-on implementation of molecular biology techniques [27]. This phase encompasses DNA synthesis, plasmid cloning, and transformation of engineered constructs into host organisms [27] [30]. For microbiome engineering, construction methods range from synthetic assembly of defined strains to self-assembly through environmental selection [3].

Advanced genetic engineering tools are increasingly automating the Build phase, reducing the time, labor, and cost of generating multiple constructs while increasing throughput [31] [30]. In high-throughput workflows, double-stranded DNA fragments are designed for easy gene construction, with assembled constructs typically cloned into expression vectors and verified with colony qPCR or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [30]. For synthetic microbial consortia, construction often involves assembling a limited number of well-characterized strains either through careful co-culturing of naturally occurring strains or using engineered strains with defined dependencies [29].

A key consideration during the Build phase is selecting an appropriate chassis organism that serves as the host for the engineered genetic constructs. For example, in biosensor development, researchers often select well-characterized bacterial strains like E. coli MG1655 due to their ease of handling, established transformation protocols, and reliable heterologous protein expression [32]. Similarly, backbone vectors must be carefully selected—such as the pSEVA261 medium-low copy number plasmid used in PFAS biosensor development—to balance gene expression needs with genetic stability [32].

Test Phase: Functional Characterization and Validation

The Test phase centers on robust data collection through quantitative measurements to characterize the behavior of engineered systems [27]. This critical evaluation stage employs various assays to measure system performance against predefined metrics, determining whether the design-build solution produced the intended objective [3].

Testing methodologies vary significantly based on application goals. For metabolic engineering projects, testing typically involves analytical chemistry techniques to quantify product formation, such as measuring dopamine production in engineered E. coli strains [31]. For therapeutic applications like anti-adipogenic protein discovery, testing might include biological assays such as Oil Red O staining to quantify lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes [27]. Biosensor development requires validation of both specificity (unique signal response to target molecule) and sensitivity (detection at low concentrations) using appropriate detection methods like fluorescence or luminescence measurements [32].

Advanced testing approaches often incorporate multi-omics technologies—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to provide comprehensive functional insights beyond simple output measurements [28]. For instance, in addition to measuring dopamine production, researchers might analyze transcriptomic data to understand system-wide responses to genetic modifications [31]. Similarly, when characterizing exosome-mediated inhibition of adipogenesis, researchers complement lipid accumulation measurements with gene expression analysis of key adipogenesis regulators (PPARγ, C/EBPα) and signaling pathway components (AMPK) to elucidate mechanistic insights [27].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Testing Engineered Microbiomes

| Application Domain | Primary Testing Methods | Key Performance Metrics | Advanced Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Engineering | HPLC, Mass spectrometry | Product titer, yield, productivity | Transcriptomics, Flux analysis |

| Biosensor Development | Fluorescence, Luminescence | Specificity, Sensitivity, Dynamic range | Dose-response characterization |

| Therapeutic Discovery | Cell-based assays, Staining | Efficacy, Toxicity, Mechanism of action | Gene expression, Pathway analysis |

Learn Phase: Knowledge Extraction and Iterative Refinement

The Learn phase represents the most critical component of the DBTL cycle, where data gathered during testing is analyzed and interpreted to extract actionable insights that inform subsequent cycles [27]. This phase addresses fundamental questions: Did the design work as expected? What principles were confirmed or refuted? Why did failures occur? [27] The knowledge gained here, whether from success or failure, drives the iterative refinement process that progressively optimizes system performance [31].