Optimizing Algal Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms: Coordination of Biophysical and Biochemical Pathways for Enhanced Carbon Fixation

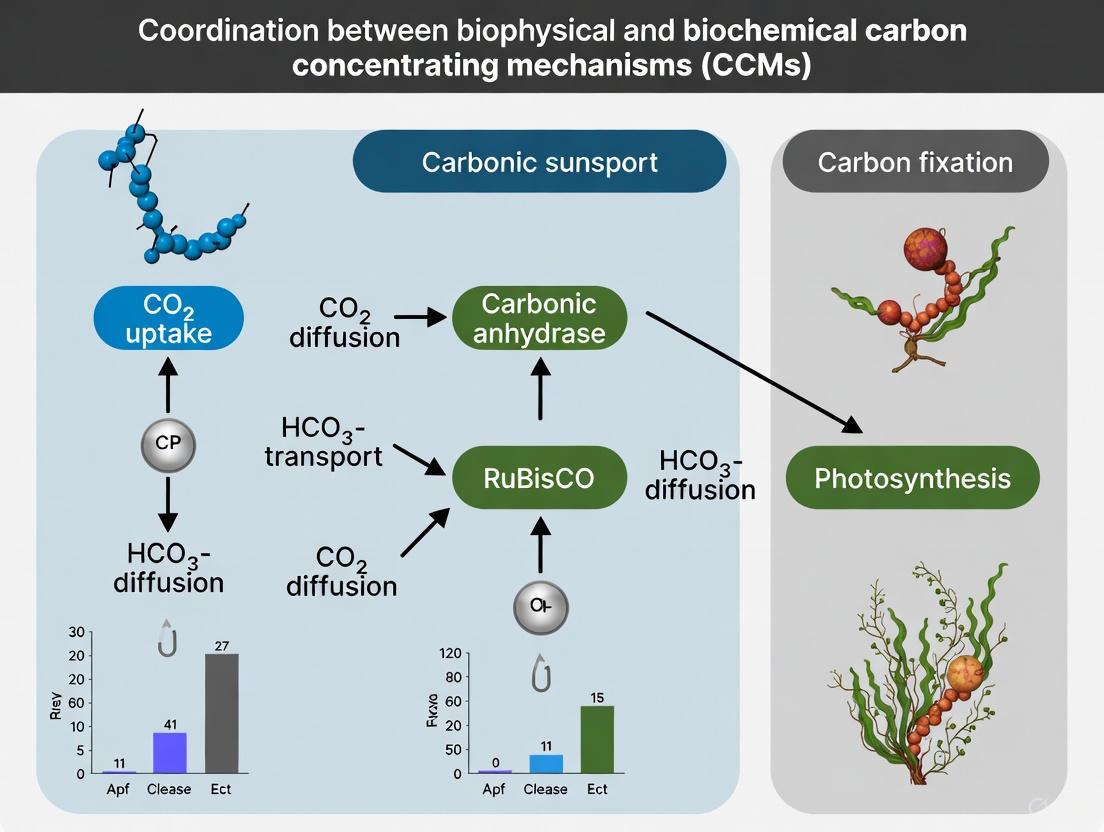

This article synthesizes current research on the coordination between biophysical and biochemical CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) in algae, a critical determinant of photosynthetic efficiency.

Optimizing Algal Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms: Coordination of Biophysical and Biochemical Pathways for Enhanced Carbon Fixation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the coordination between biophysical and biochemical CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) in algae, a critical determinant of photosynthetic efficiency. Targeting researchers and biotechnology professionals, we explore the foundational principles of these mechanisms, their dynamic interplay under varying environmental conditions, and advanced methodologies for their study and manipulation. The review covers experimental approaches for assessing relative CCM contributions, discusses troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance carbon fixation, and validates findings through comparative analysis of model species and synthetic biology applications. By integrating foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodological advances, this work aims to provide a comprehensive framework for leveraging algal CCMs to improve biofuel production, carbon sequestration technologies, and biomedical applications.

Fundamental Principles of Algal Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms: Structure, Function, and Environmental Regulation

Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) are vital adaptive strategies that enable photosynthetic organisms to overcome the limitations of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), the key enzyme for carbon fixation. When environmental CO2 is limited, Rubisco's oxygenase activity competes with its carboxylase function, leading to photorespiration—a process that consumes energy and releases previously fixed carbon. CCMs actively increase the CO2 concentration around Rubisco's active site, thereby enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and reducing photorespiratory losses [1].

Two principal CCM types have evolved: biophysical CCMs rely on inorganic carbon transport and conversion through proteins and enzymes like carbonic anhydrases, while biochemical CCMs (such as C4 photosynthesis) utilize intermediate organic acids to shuttle carbon [1] [2]. In aquatic environments, where CO2 availability is particularly low, most microalgae and some macroalgae employ biophysical CCMs. However, research indicates that many species, including the green macroalga Ulva prolifera, operate both mechanisms in a complementary manner [2] [3] [4]. Understanding and optimizing the coordination between these systems represents a frontier in algal research with significant implications for biotechnology, climate change mitigation, and fundamental knowledge of global carbon cycling.

Core Concepts: Distinguishing the Two CCMs

What are the fundamental differences between biophysical and biochemical CCMs?

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between biophysical and biochemical carbon concentrating mechanisms.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Biophysical and Biochemical CCMs

| Feature | Biophysical CCM | Biochemical CCM (C4-like) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | "Inorganic" mechanism; directly concentrates COâ‚‚ using transporters and compartmentalization [2]. | "Organic" mechanism; uses C4 acid intermediates to shuttle and release COâ‚‚ [2]. |

| Key Components | Carbonic anhydrases (CA), bicarbonate transporters (e.g., HLA3, LCIA), pyrenoid [5] [4]. | C4 enzymes: PEPC, PEPCK, PPDK [2] [4]. |

| Carbon Species Transported | Inorganic Carbon (COâ‚‚, HCO₃â») [2]. | Organic Carbon (C4 acids like malate, aspartate) [2]. |

| Energetic Cost | Consumes ATP for active transport of inorganic carbon [1]. | Consumes additional ATP/equivalent for the carboxylation-decarboxylation cycle. |

| Primary Function | Directly elevate COâ‚‚ at Rubisco site, suppressing photorespiration [1]. | Act as a biochemical pump to concentrate COâ‚‚ in specific cells or compartments. |

How do biophysical and biochemical CCMs coordinate in algae?

Research on the green macroalga Ulva prolifera reveals that its two CCMs do not operate in isolation but form a dynamic, complementary system. Inhibitor studies provide clear evidence of this coordination:

- When the biophysical CCM is inhibited by EZ (a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor), carbon fixation declines. Concurrently, cyclic electron flow around photosystem I increases, indicating the biochemical CCM becomes more active and can compensate for approximately 50% of the total carbon fixation [2] [6].

- Conversely, when the biochemical CCM is inhibited by MPA (a PEPCK inhibitor), the biophysical CCM is reinforced and can compensate for nearly 100% of the total carbon fixation [2] [6].

This plasticity allows U. prolifera to maintain high photosynthetic rates under fluctuating environmental conditions, contributing to its ability to form massive green tides [2]. The following diagram illustrates the coordinated workflow of these mechanisms and how researchers can probe them experimentally.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

This section details key reagents, inhibitors, and model organisms used to dissect the functions of biophysical and biochemical CCMs.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CCM Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) | Inhibits carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity [2]. | Suppresses the biophysical CCM. Used to assess its contribution to carbon fixation and to study compensatory mechanisms. |

| 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) | Inhibits phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) [2]. | Suppresses the biochemical CCM. Used to quantify its role and the compensatory capacity of the biophysical CCM. |

| Acetazolamide (AZ) | Inhibits external, periplasmic carbonic anhydrase [2]. | Specifically targets the extracellular component of the biophysical CCM. |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Unicellular green alga with a well-characterized biophysical CCM and pyrenoid [5] [7] [8]. | A primary model organism for genetic studies, protein localization, and fundamental CCM research. |

| Ulva prolifera | Green macroalga known to operate both biophysical and biochemical CCMs [2] [3] [4]. | An ideal model for studying the coordination and environmental regulation of multiple CCMs. |

| Lucidone C | Lucidone C, CAS:102607-23-8, MF:C24H36O5, MW:404.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diminazene | Diminazene, CAS:536-71-0; 908-54-3, MF:C14H15N7, MW:281.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Data from Key Experiments

The following table compiles critical quantitative findings from recent studies, providing a reference for expected experimental outcomes.

Table 3: Key Quantitative Findings in CCM Research

| Observation / Parameter | Quantitative Value | Context / Organism | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical CCM Compensation | ~50% of total carbon fixation | Contribution when biophysical CCM is inhibited in Ulva prolifera [2]. | |

| Biophysical CCM Compensation | ~100% of total carbon fixation | Capacity to compensate when biochemical CCM is inhibited in Ulva prolifera [2]. | |

| Km (CO₂) for U. prolifera | ~250 µM | Half-saturation constant for photosynthesis; much higher than ambient seawater CO₂ (5-25 µM) [4]. | |

| Critical PCOâ‚‚ for CCM Efficiency | As low as found in plants with biochemical CCMs (C4/CAM) | Level at which adding a biophysical CCM becomes energetically favorable in C3 plants [1]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low carbon fixation efficiency in mutant algal strains.

- Question: How can I determine if the defect is in the CCM or another photosynthetic process?

- Solution:

- Measure photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution or carbon fixation rates across a range of DIC concentrations to generate a P-C curve. An increased half-saturation constant (Kâ‚/â‚‚DIC) suggests impaired CCM activity [3] [4].

- Conduct experiments under photorespiratory (21% Oâ‚‚) and non-photorespiratory (2% Oâ‚‚) conditions. If the growth defect is rescued under low Oâ‚‚, the problem likely lies with the CCM's inability to suppress photorespiration effectively [7].

- Check for proper pyrenoid morphology and Rubisco localization. Mutants with disrupted pyrenoids (e.g., Chlamydomonas) show impaired fatty acid biosynthesis and carbon fixation, linking CCM function to other metabolic pathways [8].

Problem: Inconsistent results when using inhibitors like EZ and MPA.

- Question: Are my inhibitor concentrations and application methods correct?

- Solution:

- Optimal Concentrations: For Ulva prolifera, a final concentration of 50 µmol/L for EZ and 1.5 mmol/L for MPA is effective in culture experiments [2]. Always perform a gradient concentration detection for a new species or strain.

- Experimental Pre-treatment: Ensure algal samples are depleted of endogenous Ci sources before inhibitor application. This is typically done by transferring fragments to Ci-free, buffered artificial seawater for 30-60 minutes [2].

- Control Experiments: Use AZ (Acetazolamide) to distinguish between external (periplasmic) and total CA activity. AZ inhibits only external CA, while EZ penetrates cells and inhibits both external and internal CA [2].

Problem: Failed heterologous expression of algal CCM components in higher plants.

- Question: I have expressed a bicarbonate transporter in a C3 plant, but see no growth enhancement. What could be wrong?

- Solution:

- Check Subcellular Localization: Algal proteins may not automatically target to the correct compartment in plant cells. For example, the algal CAH6 and the putative Ci transporter LCI1 required fusion to an Arabidopsis chloroplast transit peptide for successful retargeting to the chloroplast [5] [9].

- Consider Component Stacking: Expression of individual Ci transporters (e.g., LCIA, HLA3) in Arabidopsis did not enhance growth. A fully functional CCM likely requires the synergistic expression of multiple components, including transporters, carbonic anhydrases, and a RuBisCO that can be packaged into a pyrenoid-like microcompartment [5] [9].

FAQs on CCM Function and Regulation

Q1: Why have biophysical CCMs not evolved more widely in land plants if they are so effective in algae?

- A1: Theoretical modeling suggests that the energy efficiency of a biophysical CCM in a typical C3 land plant leaf is highly dependent on factors like membrane permeability to CO₂. Under many conditions, the energetic cost of operating the CCM can be higher than the cost of photorespiration, making it unfavorable. The exception is in environments with very low CO₂ availability or low gas conductance, as seen in hornworts—the only land plants with a biophysical CCM [1].

Q2: Does the induction of a CCM completely suppress photorespiration in algae?

- A2: No, recent evidence challenges this long-held view. In Chlamydomonas, photorespiration remains active even when the CCM is operational under low COâ‚‚. Glycolate excretion and the down-regulation of glycolate dehydrogenase may serve as a safety valve to prevent the toxic accumulation of photorespiratory metabolites, indicating an integrated and dynamic relationship between CCM and photorespiration [7].

Q3: How do I know which CCM is dominant in the algal species I am studying?

- A3: The dominant mechanism can be environment-dependent. A combination of transcriptomics (looking for genes like HLA3, LCI1, PEPC, PEPCK), enzyme activity assays, and inhibitor studies (using EZ and MPA) is most effective. For example, in Ulva prolifera, the biophysical CCM is generally dominant, but the biochemical CCM can contribute significantly under specific stresses or when the biophysical CCM is impaired [2] [3].

Q4: Are there unexpected metabolic connections to the algal CCM?

- A4: Yes. Cutting-edge research shows that the pyrenoid, the core of the algal biophysical CCM, also plays a role in fatty acid biosynthesis. Under COâ‚‚ limitation, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) subunits localize to the pyrenoid periphery. Disrupting the pyrenoid impairs fatty acid and triacylglycerol biosynthesis, revealing a direct link between the CCM and carbon allocation to energy-rich storage compounds [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My experiment shows negligible carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity in Chlamydomonas under low CO2, contrary to expectations. What could be wrong? The expression of carbonic anhydrases is highly specific. In Chlamydomonas, only a subset of CAs is strongly upregulated under low CO2. Transcriptomic studies reveal that among the twelve annotated CAs, primarily CAH1, CAH4, and CAH5 show significant induction (>2 fold-change) under low-CO2 conditions. Other isoforms may be downregulated or not induced. Confirm you are measuring the activity of the correct isoforms. Furthermore, note that a Cah1 mutant shows no apparent growth or photosynthetic phenotype, indicating it is not essential for the CCM, whereas a Cah3 mutant (thylakoid lumen-localized) is impaired in photosynthesis and exhibits a high-CO2-requiring phenotype [10].

Q2: I am observing inconsistent localization of introduced bicarbonate transporters in my transgenic plant model. How can I improve this? Retargeting algal components to appropriate organelles in higher plants can be challenging. A study expressing the algal plasma membrane transporter LCI1 in tobacco successfully redirected it to the chloroplast by fusing it to an Arabidopsis chloroplast transit peptide. Similarly, the chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase CAH6, which is naturally secreted in algae, was also retargeted to the chloroplast using the same strategy. Ensure your construct includes a validated transit peptide for your target organism and organelle [9].

Q3: How can I experimentally distinguish the activity of a C4-like pathway from the biophysical CCM in my algal cultures? The two mechanisms can be disentangled using enzyme-specific inhibitors and controlled conditions.

- Inhibitor Studies: Use the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPCase)-specific inhibitor 3,3-dichloro-2-dihydroxyphosphinoylmethyl-2-propenoate (DCDP). In the diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii, DCDP inhibition led to a >90% decrease in photosynthesis at low CO2, which was rescued by elevated CO2 or low O2, linking PEPCase activity to CO2 supply. This effect was minimal in the C3 green alga Chlamydomonas sp., where PEPCase serves a primarily anaplerotic role [11].

- Environmental Response: Monitor enzyme activity under varying light and CO2. Research on Ulva prolifera showed that key C3 enzyme (Rubisco) activity peaks in the morning, while C4 enzymes (PEPCase, PEPCKase) peak at noon under high irradiance, indicating a light-dependent role for the C4 pathway [12].

Q4: Why is my Chlamydomonas lci20 mutant showing a growth defect only during a sudden shift to very low CO2, but not when pre-acclimated? The LCI20 protein is a chloroplast envelope glutamate/malate transporter integral to photorespiration. During a sudden, severe CO2 limitation, the coordination between the rapidly induced CCM and photorespiratory metabolism becomes critical. LCI20 is proposed to supply amino groups for the mitochondrial conversion of glyoxylate to glycine. If this exchange is disrupted, photorespiratory metabolites can accumulate to toxic levels, impairing growth. In pre-acclimated cells, other compensatory mechanisms may be up-regulated to mitigate this defect [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Issues with Bicarbonate Transport Assays

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| No HCO3- uptake detected in heterologous system (e.g., Xenopus oocytes). | Transporter not correctly localized to plasma membrane. | Confirm membrane localization with immunocytochemistry. For plant transporters, use an oocyte system validated for plant membrane proteins. |

| The expressed protein is a channel, not an active transporter. | Perform electrophysiology measurements to detect passive, channel-mediated flux. | |

| Inconsistent H14CO3- uptake rates in algal cultures. | Energy supply to the transporter is compromised. | Ensure cultures are well-lit; consider that cyclic electron flow (CEF) and mitochondrial respiration are key energy sources for transporters like HLA3 [13]. |

| The specific transporter is not induced. | Confirm the culture is properly acclimated to low CO2 conditions and check transcript levels of the target transporter (e.g., HLA3, LCIA). |

Resolving Problems in C4 Enzyme Activity Measurements

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low or no detectable PEPCase/PEPCKase activity in algal cell extracts. | Enzyme instability during extraction. | Include protease inhibitors and stabilizing substrates (e.g., PEP) in the extraction buffer. Perform extraction rapidly on ice. |

| Incorrect assumption of C4 pathway activity in the species. | Genomically verify the presence of key C4 enzymes (PEPCase, PEPCKase, PPDKase). Do not rely solely on PPDKase, as its role may be in photoprotection [12]. | |

| High background noise in radiometric assays. | Inefficient separation of metabolites. | Use validated separation methods like silicone oil centrifugation for short-term 14C uptake experiments [11]. |

Key Bicarbonate Transporters in Model Organisms

Table 1: Characteristics of selected bicarbonate transporters.

| Transporter | Organism | Gene | Function / Role | Key Characteristics / Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA3 | Chlamydomonas | Cre02.g097800 | Ci uptake into cytosol [9]. | ABC-type transporter, plasma membrane, induced under very low CO2 [9] [7]. |

| LCIA | Chlamydomonas | Cre06.g309000 | Ci transport from cytosol to stroma [9]. | Putative HCO3- channel, chloroplast envelope [9]. |

| BicA | Cyanobacteria | N/A | Na+-dependent HCO3- transporter [14]. | Low-affinity, high-flux, SulP family [14]. |

| SbtA | Cyanobacteria | N/A | Na+-dependent HCO3- transporter [14]. | High-affinity, low-flux [14]. |

| AE1 | Human | SLC4A1 | Cl-/HCO3- exchange [15]. | Acid loader; 911 amino acids, 13 transmembrane segments [15]. |

| NBCe1 | Human | SLC4A4 | Na+/HCO3- cotransport (electrogenic) [15]. | Acid extruder; 1035 amino acids [15]. |

Enzyme Activity Ranges in Algae

Table 2: Representative enzyme activities in algae under different conditions. NA: Data Not Available in the provided search results.

| Enzyme | Organism | Condition | Activity (nmol·minâ»Â¹Â·gFWâ»Â¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubisco (C3) | Ulva prolifera | Sunny day, 10:00 h | 274 | Activity drops significantly at noon [12]. |

| PEPCase (C4) | Ulva prolifera | Sunny day, noon | Peak Activity | Activity is high and correlates with irradiance [12]. |

| PEPCKase (C4) | Ulva prolifera | Sunny day | High | Significantly higher than on a cloudy day [12]. |

| PEPCase | T. weissflogii | Low CO2 (10 μM) | Functional | Inhibition causes >90% drop in photosynthesis [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Confirming HCO3- Transport Function inXenopusOocytes

Application: Functional characterization of putative bicarbonate transporters (e.g., LCIA, HLA3) [9]. Principle: The cRNA of the transporter is injected into oocytes. HCO3- uptake is quantified by measuring radioactivity (H14CO3-) in the oocytes after incubation.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Clone and Prepare cRNA: Clone the full-length coding sequence of the transporter gene into an oocyte expression vector (e.g., pOX). In vitro transcribe capped cRNA.

- Inject Oocytes: Defolliculate Stage V-VI Xenopus laevis oocytes. Inject 50 nL of cRNA (or water as a negative control) per oocyte. Incubate at 16°C in Barth's solution for 2-3 days to allow for protein expression.

- Uptake Assay: Wash oocytes in a CO2/HCO3--free buffer (e.g., ND96). Transfer groups of 10-15 oocytes to uptake solution (pH X.X) containing 1-2 µCi of H14CO3-.

- Terminate and Quantify: After a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes), rapidly wash oocytes with ice-cold, non-radioactive uptake solution to stop the reaction. Lyse individual oocytes and quantify radioactivity via liquid scintillation counting.

- Data Analysis: Compare H14CO3- uptake in cRNA-injected oocytes to water-injected controls. Statistically significant increases confirm transport function.

Protocol: Assessing theIn VivoRole of C4 Metabolism using PEPCase Inhibition

Application: Determining the contribution of the C4 pathway to overall photosynthetic carbon fixation in diatoms and algae [11]. Principle: The specific PEPCase inhibitor DCDP is used to block the initial carboxylation step of the C4 pathway. The subsequent impact on photosynthesis is measured via O2 evolution.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Culture and Acclimate: Grow algal cells (e.g., Thalassiosira weissflogii) in air-equilibrated medium to acclimate them to low CO2 conditions.

- Inhibitor Incubation: Resuspend cell aliquots in fresh medium with or without the PEPCase inhibitor DCDP (e.g., 1 mM). Pre-incubate for a defined period (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Measure Photosynthesis: Transfer cell suspensions to an O2 electrode chamber. Illuminate at saturating light intensity and measure the rate of photosynthetic O2 evolution.

- Rescue Experiments: To confirm the effect is due to limited CO2 supply, repeat the inhibition assay under elevated CO2 (e.g., 150 µM) or low O2 (e.g., 80-180 µM) conditions. Recovery of photosynthesis under these conditions supports the role of PEPCase in a CCM.

- Interpretation: A strong suppression of O2 evolution by DCDP at low CO2 that is rescued by high CO2/low O2 indicates a major role for the C4 pathway in carbon accumulation.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Carbon Concentration Mechanism Coordination

Diagram Title: Coordination of Biophysical and Biochemical CCM Components

Experimental Workflow for CCM Component Analysis

Diagram Title: Functional Analysis Workflow for CCM Components

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and their applications in algal CCM research.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DCDP (3,3-dichloro-2-dihydroxyphosphinoylmethyl-2-propenoate) | Specific inhibitor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPCase). Used to dissect C4 metabolism contribution to photosynthesis [11]. | In T. weissflogii, 1 mM DCDP caused >90% decrease in O2 evolution at low CO2 [11]. |

| Mercaptopicolinic acid | Inhibitor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCKase). Used to probe decarboxylation steps in C4 metabolism [11]. | Used in cell extraction solutions to inhibit PEPCKase during 14C uptake assays [11]. |

| H14CO3- | Radioactive tracer for measuring bicarbonate uptake and flux in various experimental systems (whole cells, oocytes) [9] [11]. | Provides direct measurement of transporter activity and carbon fixation pathways. |

| Chloroplast Transit Peptides | Protein sequences used to retarget algal proteins (e.g., transporters, CAs) to chloroplasts in plant transformation experiments [9]. | An Arabidopsis transit peptide successfully retargeted algal CAH6 and LCI1 to chloroplasts in tobacco [9]. |

| Antibodies (Specific) | Tools for detecting protein expression, localization (immunocytochemistry), and confirming knockout mutants. | An LCI20 antibody was used to confirm the absence of the protein in the lci20 Chlamydomonas mutant [7]. |

| Xenopus laevis Oocytes | Heterologous expression system for characterizing the function of ion transporters and channels [9]. | Validated for functional expression of algal Ci transporters like LCIA and HLA3 [9]. |

| Valtrate hydrine B4 | Valtrate hydrine B4, MF:C27H40O10, MW:524.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bph-742 | Bph-742, MF:C16H37O6P3, MW:418.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Pyrenoid Function and Experimental Analysis

FAQ 1: What is the primary function of the pyrenoid? The pyrenoid is a phase-separated organelle found in the chloroplasts of most eukaryotic algae and hornworts. Its main function is to serve as the central hub for a biophysical CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) that enhances photosynthetic carbon assimilation. It concentrates CO2 around the enzyme Rubisco, thereby increasing its carboxylation rate and suppressing wasteful photorespiration [16] [17].

FAQ 2: My experiment shows low carbon fixation efficiency in a pyrenoid-deficient mutant. What is the underlying cause? This is an expected phenotype. The functional value of the pyrenoid matrix is to concentrate CO2 for Rubisco. Mutants with disrupted pyrenoids lack this concentrated CO2 supply, leading to increased Rubisco oxygenation and reduced carbon fixation efficiency. Research shows that preventing Rubisco condensation into a pyrenoid matrix carries a clear fitness cost [16].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally distinguish the activity of a biophysical CCM from a biochemical CCM in my algal samples? You can use specific enzyme inhibitors in culture experiments to dissect the contributions of each mechanism.

- To inhibit the biophysical CCM: Use carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitors like Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) or Acetazolamide (AZ). These block the interconversion of HCO3- and CO2, which is crucial for biophysical carbon concentration [2].

- To inhibit the biochemical CCM: Use 3-mercaptopicolinic acid (MPA), an inhibitor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), a key enzyme in the C4-like biochemical pathway [2]. The relative contribution of each CCM can be estimated by measuring changes in photosynthetic parameters (e.g., O2 evolution, carbon fixation rates) upon addition of these inhibitors [2].

FAQ 4: Why is a diffusion barrier considered critical for an efficient pyrenoid-based CCM? Computational models demonstrate that without a barrier to slow CO2 leakage, most CO2 generated within the pyrenoid escapes without being fixed by Rubisco. This creates a futile cycle where energy is wasted to concentrate CO2 that then diffuses away. The cell must expend additional energy to recapture this escaped CO2, making the CCM energetically inefficient. Models show that adding a diffusion barrier drastically reduces this leakage, enabling high Rubisco saturation (e.g., ~80%) at a lower energy cost (2-4 ATP per CO2 fixed) [18] [19].

FAQ 5: What are the known components of the pyrenoid in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii? The core molecular components in C. reinhardtii include:

- Rubisco: The main matrix component, assembled via interactions with EPYC1 [17].

- EPYC1 (Essential Pyrenoid Component 1): An intrinsically disordered linker protein essential for forming the phase-separated Rubisco matrix [17].

- SAGA1 and MITH1: Proteins necessary for forming the thylakoid membrane tubules that traverse the pyrenoid to deliver HCO3- [17].

- CAH3: A carbonic anhydrase located in the thylakoid lumen within the pyrenoid that converts HCO3- to CO2 [18].

- LCIB/LCIC: A protein complex forming a layer around the pyrenoid, hypothesized to recapture escaped CO2 [17].

- BST1-3: Putative HCO3- channels that allow HCO3- to move from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Pyrenoid Induction in Algal Cultures

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate control of CO2 levels in the growth environment. The pyrenoid and CCM are highly inducible, primarily by low CO2 conditions [17].

- Solution: Pre-acclimate cultures to the target CO2 condition (e.g., high CO2 vs. air-level vs. very low CO2) for a sufficient period (≥24 hours). Use precise gas mixing systems or bubbled air with verified CO2 content for consistent results [20].

- Cause 2: Variations in light intensity during culture.

- Solution: Standardize light quantum levels and photoperiods across experiments, as light availability is a key regulator of photosynthesis and can influence CCM induction [2].

- Cause 3: Cell cycle effects. The pyrenoid partially dissolves and re-condenses during cell division [16] [17].

- Solution: Use synchronized cultures or sample cells at the same growth phase (e.g., mid-logarithmic phase) to minimize variability.

Problem: High CO2 Leakage in Pyrenoid Function Models

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of or defective diffusion barrier. Modeling indicates that a physical barrier is essential to reduce futile CO2 cycling [18] [19].

- Solution 1 (In vivo): In species like Chlamydomonas, ensure the integrity of the starch sheath, which can act as a diffusion barrier. Mutants with thinner or absent starch sheaths (e.g., sta2-1, sta11-1) show decreased CCM efficacy at low CO2 [19].

- Solution 2 (In silico): When constructing computational models, explicitly include a diffusion barrier with low permeability (on the order of 10â»â´ m/s) around the pyrenoid matrix to accurately simulate its function [19].

Problem: Difficulty in Distinguishing Between Multiple CCMs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Organisms can employ complementary CCMs. Some algae, like Ulva prolifera and Nannochloropsis oceanica, can operate both biophysical and biochemical (C4-like) CCMs, which may be coordinated or compensate for each other [2] [20].

- Solution: Implement a multi-omics approach. As demonstrated in N. oceanica, track transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles over time during a shift from high to low CO2. This can identify the coordinated upregulation of key genes and proteins specific to each CCM type, such as bicarbonate transporters/CAs for the biophysical CCM and PEPC/PEPCK for the biochemical CCM [20].

Data Presentation

Key Experimental Reagents for Pyrenoid and CCM Research

Table 1: Essential research reagents for studying pyrenoid-based carbon concentrating mechanisms.

| Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function in Experiments | Key Application/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) | Inhibitor | Inhibits carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity [2]. | Used to suppress the biophysical CCM; inhibits both extracellular and intracellular CA [2]. |

| Acetazolamide (AZ) | Inhibitor | Inhibits carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity [2]. | Used to suppress the biophysical CCM; primarily targets external periplasmic CA [2]. |

| 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) | Inhibitor | Inhibits phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) [2]. | Used to suppress the biochemical C4-like CCM [2]. |

| EPYC1 Knockout Mutants | Genetic Tool | Lacks the linker protein essential for pyrenoid matrix formation in C. reinhardtii [17]. | Used to study pyrenoid assembly and the functional impact of a disrupted Rubisco matrix [17]. |

| Starch Sheath Mutants (e.g., sta2-1) | Genetic Tool | Possesses a thinner or absent pyrenoid starch sheath [19]. | Used to investigate the role of the starch sheath as a potential CO2 diffusion barrier [19]. |

Quantitative Metrics for PCCM Performance

Table 2: Key quantitative metrics used to evaluate the efficacy and efficiency of the pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanism (PCCM) from computational and experimental studies.

| Performance Metric | Description | Interpretation | Reported Values/Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rubisco Saturation | The extent to which Rubisco active sites are occupied by CO2, relative to the maximum possible rate [18]. | Directly measures PCCM efficacy. Higher saturation indicates a more effective CO2 concentration. | A model with an efficient PCCM can achieve ~80% saturation [19]. |

| ATP cost per COâ‚‚ fixed | The total number of ATP molecules consumed to fix one molecule of COâ‚‚ [18]. | Measures PCCM energetic efficiency. Lower cost is more efficient. | A passive-uptake PCCM can theoretically cost 2-3 ATP/COâ‚‚; an active mode costs 3-4 ATP/COâ‚‚ [19]. |

| Ci (Inorganic Carbon) Affinity | The ability of the cell to uptake Ci (COâ‚‚ + HCO₃â») from the external environment at low concentrations. | Indicates the activity of Ci uptake systems. Higher affinity is characteristic of an induced CCM. | Measured experimentally in mutants (e.g., starch sheath mutants show decreased affinity) and used to fit models [19]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing CCM Contributions Using Specific Inhibitors

This protocol is adapted from studies on Ulva prolifera to distinguish the relative contributions of biophysical and biochemical CCMs to photosynthetic carbon fixation [2].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Clark-type oxygen electrode system.

- Buffered artificial seawater (e.g., 20 mmol/L Hepes-NaOH, pH 8.0).

- Inhibitor stock solutions: 50 mmol/L Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) in DMSO, 1.5 mol/L 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) in DMSO.

- NaHCO₃ solution.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Culture Acclimation: Grow algal samples under the desired COâ‚‚ condition (e.g., high COâ‚‚ vs. air-level) for at least 24-48 hours to fully induce or repress the CCM.

- Ci Depletion: Cut algal samples into small fragments and transfer them to buffered artificial seawater that has been pre-aerated with Nâ‚‚ at low pH to remove dissolved COâ‚‚. Incubate for 30 minutes to deplete internal inorganic carbon pools.

- Inhibitor Application: Distribute the Ci-depleted samples into the reaction vessel of the O₂ electrode system. Add inhibitors to the respective treatment groups to achieve final concentrations of 50 μmol/L EZ (for biophysical CCM inhibition) or 1.5 mmol/L MPA (for biochemical CCM inhibition). Include a control group with an equivalent volume of solvent (DMSO).

- Measurement: Add NaHCO₃ to all samples to a final concentration of 2 mmol/L. Measure the steady-state rate of photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution under saturating light (e.g., 200 μmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage inhibition for each CCM pathway using the formula:

% Inhibition = 100 x [1 - (Rate with inhibitor / Rate without inhibitor)]. The results indicate the relative contribution of each CCM to total carbon fixation under the tested conditions [2].

Protocol: Multi-Omics Analysis for CCM Identification

This protocol outlines a systems biology approach to identify components of multiple CCMs, as demonstrated in Nannochloropsis oceanica [20].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Environmental Shift and Sampling: Grow a batch culture under high COâ‚‚ (e.g., 50,000 ppm). Harvest a sample for the "0-hour" time point. Then, rapidly transfer the culture to a very low COâ‚‚ (VLC) environment (e.g., 100 ppm). Collect subsequent samples at multiple time points (e.g., 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours post-shift) [20].

- Multi-Omics Profiling:

- Transcriptomics: Extract mRNA and perform RNA-Seq for all time points under both HC and VLC conditions. Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in VLC compared to HC [20].

- Proteomics: Analyze protein extracts using mass spectrometry. Identify proteins that show significant changes in abundance in response to VLC [20].

- Metabolomics: Analyze metabolite pools to track changes in intermediates of the Calvin cycle, photorespiration, and potential C4 acids [20].

- Integrated Data Analysis:

- Triangulation: Cross-reference transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets to identify robust, coordinated responses to VLC.

- Functional Annotation: Map the induced genes/proteins to specific CCM types:

- Biophysical CCM: Look for significant upregulation of genes encoding bicarbonate transporters (BCTs) and various carbonic anhydrases (CAs) [20].

- Biochemical CCM: Look for induction of key C4-like pathway enzymes (e.g., PEPC, PEPCK, malate enzyme) at both the transcript and protein levels, alongside accumulation of C4 acids [20].

- Basal CCM: Investigate the upregulation of genes related to photorespiration and mitochondrial CO2 recycling systems [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for pyrenoid and CCM research.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Mutant Library | A resource for identifying genes essential for pyrenoid function, CCM, and related processes via screening of targeted or random mutants [16]. |

| Fluorescently Tagged Protein Lines | Strains with fluorescently tagged pyrenoid components (e.g., EPYC1, Rubisco, LCIB) for visualizing protein localization and pyrenoid dynamics in vivo [16]. |

| Pyrenoid Proteome & Proxiome Datasets | Comprehensive lists of proteins localized to the pyrenoid and their interaction networks, providing a basis for hypothesizing protein functions [16]. |

| Computational (Reaction-Diffusion) Model of the PCCM | A quantitative framework to test hypotheses about PCCM operation, predict the impact of perturbations, and guide engineering strategies [18] [19]. |

| Fosfazinomycin B | Fosfazinomycin B, MF:C10H23N6O6P, MW:354.30 g/mol |

| DHA Ceramide | DHA Ceramide, MF:C40H67NO3, MW:610.0 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My algal cultures are not achieving the expected biomass yield despite adequate CO2 supplementation. What are the key environmental factors I should optimize?

- Answer: Biomass yield is a function of several interdependent environmental factors. Beyond CO2, you must systematically optimize light, temperature, and nutrients. Recent research using machine learning models has identified that CO2 concentration and pH are often the most influential factors, followed by light colour (wavelength) and temperature [21]. Ensure your cultivation system allows for independent control and monitoring of these parameters. Use the table below (Summary of Optimal Environmental Conditions for Algal Biomass and Lipids) as a starting point for optimization.

FAQ 2: How can I non-destructively monitor the physiological status of my algal cultures in real-time during CCM experiments?

- Answer: Chlorophyll a fluorescence is a powerful, non-invasive technique to probe the efficiency of photosystem II (PSII), which is directly linked to the photosynthetic electron transport chain and affected by CCM activity [22] [23]. Parameters such as the maximum quantum yield of PSII (

Fv/Fm) provide a sensitive measure of photochemical efficiency and can indicate stress long before changes in biomass are detectable. Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) fluorometers are specifically designed for these measurements, even in ambient light conditions [23].

FAQ 3: I observe a discrepancy between high electron transport rates (inferred from fluorescence) and low carbon fixation rates. What does this indicate?

- Answer: This disconnect often points to processes that consume reducing power without fixing carbon. A primary suspect is the induction of photorespiration [22] [23]. This can occur when the CCM is not fully active or is overwhelmed, leading to oxygenase activity by Rubisco. To confirm, simultaneously measure chlorophyll fluorescence and gas exchange (CO2 fixation). An increased electron requirement per molecule of CO2 fixed is a clear indicator of photorespiratory activity [23].

FAQ 4: Why does the chlorophyll content of my algal samples vary significantly under different nutrient regimes, and how does this affect my biomass estimates?

- Answer: Chlorophyll content per cell is a dynamic photoacclimation parameter. Under low light, cells increase chlorophyll to harvest more energy. Crucially, nutrient availability, especially nitrogen, strongly modulates this, as chlorophyll molecules are nitrogen-rich [24]. Under nitrogen limitation, cellular chlorophyll decreases, meaning that chlorophyll concentration can be a poor proxy for actual algal carbon biomass [24]. Always consider the Chlorophyll-to-Carbon (Chl:C) ratio for accurate biomass estimation under varying nutrient and light conditions.

FAQ 5: What is the most critical step when measuring the Fv/Fm parameter to assess the maximal PSII efficiency?

- Answer: Proper dark adaptation is essential. Samples must be dark-adapted for a sufficient period (typically 15-30 minutes) to ensure all PSII reaction centers are fully "open" and non-photochemical quenching is relaxed [22] [23]. Failure to do so will result in an underestimation of

Fv/Fmand an incorrect diagnosis of your culture's physiological state.

The following table consolidates optimal environmental conditions for maximizing algal biomass and lipid production, as identified in experimental studies.

Table 1: Summary of Optimal Environmental Conditions for Algal Biomass and Lipids

| Environmental Factor | Optimal Condition for Biomass/Lipids | Observed Effect / Quantitative Outcome | Key Genera Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| COâ‚‚ Concentration | 9% | Significant positive correlation with lipid content (7.2–24.5%) and biomass (0.2–2.1 g Lâ»Â¹) [21]. | Chlorella, Botryococcus, Chlamydomonas, Tetraselmis, Closterium [21] |

| pH | 7 (Neutral) | Identified as a top-tier influential factor for growth and biochemical composition [21]. | Chlorella, Botryococcus, Chlamydomonas, Tetraselmis, Closterium [21] |

| Light Colour (Wavelength) | Red LED | Promoted the best growth rates in algal cultures [21] [25]. | Chlorella spp. and Chondracanthus acicularis (red seaweed) [21] [25] |

| Light Intensity | 3000 lux | Optimized biomass production under laboratory conditions [21]. | Chlorella, Botryococcus, Chlamydomonas, Tetraselmis, Closterium [21] |

| Temperature | 30°C | Supported optimal growth and biochemical productivity [21]. | Chlorella, Botryococcus, Chlamydomonas, Tetraselmis, Closterium [21] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ChlorophyllaFluorescence Measurement for PSII Health

This protocol is critical for non-invasively monitoring the photochemical performance of your algae, which is modulated by CCM activity [22] [23].

- Principle: The yield of chlorophyll fluorescence is inversely related to the photochemical efficiency of PSII. Measuring the fluorescence parameters provides insights into the energy partitioning within photosynthesis [23].

- Key Parameters:

- Fv/Fm: Maximum quantum yield of PSII. Values ~0.65-0.83 indicate healthy, unstressed phytoplankton. Lower values indicate photoinhibition or other stresses [23] [24].

- ΦPSII (Y(II)): Effective quantum yield of PSII under actinic (measuring) light. Estimates the rate of linear electron transport [23].

- Procedure:

- Dark Adaptation: Dark-adapt an algal sample for at least 15-20 minutes to ensure all reaction centers are open and relax non-photochemical quenching [22] [23].

- Measurement: Use a PAM fluorometer.

- Fâ‚€ Measurement: Apply a weak, modulated measuring beam to determine the minimum fluorescence yield.

- Fm Measurement: Apply a saturating pulse of light (e.g., 0.2-1s) to close all PSII reaction centers and measure the maximum fluorescence yield.

- Calculation: Calculate variable fluorescence

Fv = Fm - Fâ‚€and then the maximum quantum yieldFv/Fm[23]. - Light-Adapted Parameters: Under actinic light, you can further measure

Fm'(light-adapted maximum fluorescence) andFt(steady-state fluorescence) to calculateΦPSII = (Fm' - Ft) / Fm'[23].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Workflow for Optimizing Environmental Factors

This modern approach efficiently navigates the complex, multi-factorial space of environmental modulators to optimize CCM performance and biomass yield [21].

- Principle: Machine learning (ML) models can analyze complex datasets from controlled experiments to predict the optimal combination of environmental factors for a desired output (e.g., high lipid content).

- Procedure:

- Factorial Experiment: Systematically culture algae across a matrix of different conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, COâ‚‚, light colour/intensity) [21].

- Data Collection: For each condition, quantify response variables such as biomass dry weight, lipid content (e.g., by gravimetric analysis after extraction), and protein content [21].

- Model Training: Use the experimental data to train ML models, such as Random Forest (RF), which has shown strong performance in this domain [21].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use the trained model to identify which environmental factors (e.g., COâ‚‚, pH) are the most influential predictors of your target output [21].

- Validation: Validate the model's predictions with a new set of experiments conducted at the predicted optimal conditions.

Signaling and Regulatory Pathways

The following diagram summarizes the regulatory network through which key environmental signals modulate the Carbon Concentrating Mechanism (CCM) in algae, integrating both biophysical and biochemical components.

Diagram: Environmental Regulation of Algal CCM. Key environmental signals are transduced into coordinated gene expression and physiological changes, optimizing the coordination between biophysical and biochemical CCM components for enhanced carbon fixation and biomass yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Algal CCM and Growth Studies

| Item | Function / Application in CCM Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bold's Basal Medium (BBM) | A standard synthetic nutrient medium for the axenic cultivation of a wide variety of freshwater algae [21]. | Provides essential macronutrients (N, P, S, Ca, Mg) and trace metals (Fe, Mn, Cu) necessary for growth [21]. |

| Provasoli's Enriched Seawater (PES) Medium | A common nutrient medium used for the cultivation of marine macroalgae and microalgae [25]. | Used in studies on red seaweeds like Chondracanthus acicularis; supports growth with a balanced nutrient profile [25]. |

| PAM Fluorometer | Measures chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters (e.g., Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, NPQ) to assess PSII photochemistry in vivo and non-destructively [22] [23]. |

Instruments like the IMAGING-PAM M-Series (Walz) allow for spatial resolution of photosynthetic performance [26]. Critical for monitoring culture health and CCM efficiency. |

| Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) Technique | The underlying methodology that allows fluorescence measurement in ambient light by using a modulated measuring beam [23]. | This is the technological foundation that makes most modern fluorescence measurements possible outside of a dark lab. |

| COâ‚‚ Air Mixing System | To precisely control and maintain specific COâ‚‚ concentrations (e.g., 5%, 9%, 11%) in the culture aeration stream [21]. | Typically involves mass flow controllers and compressed air/COâ‚‚ gas tanks. Essential for studying CCM induction and its environmental modulation. |

| LED Light Panels (Multi-color) | To provide specific light wavelengths (e.g., red, blue, white) for studying the impact of light quality on photosynthesis and CCM activity [21] [25]. | Red light has been shown to promote optimal growth in several algal and seaweed species [21] [25]. |

| Nikkomycin Lx | Nikkomycin Lx, MF:C21H27N5O9, MW:493.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isariin D | Isariin D, MF:C26H45N5O7, MW:539.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of photosynthetic research, Rubisco (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) presents a fundamental evolutionary puzzle. This key enzyme, responsible for carbon fixation during photosynthesis, is constrained by a well-documented inverse relationship between its specificity for COâ‚‚ versus Oâ‚‚ and its catalytic turnover rate. This trade-off directly impacts the efficiency of carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms. For researchers engineering algal strains for enhanced carbon capture or biofuel production, understanding and navigating this trade-off is crucial for optimizing the coordination between biophysical and biochemical COâ‚‚ concentrating mechanisms (CCMs). This guide addresses the experimental challenges and solutions for investigating this critical relationship within the context of algal CCM optimization.

Key Concepts & Theoretical Framework

The Stability-Activity Trade-Off

Research on the adaptive evolution of Rubisco in C3 and C4 plants reveals that the enzyme's evolution has been constrained by stability-activity trade-offs [27]. The evolutionary shift from C3 to C4 photosynthesis involved a small number of mutations under positive selection that enhanced COâ‚‚ turnover rate at the cost of reduced COâ‚‚ specificity and structural stability [27].

- Molecular Mechanism: These adaptive mutations are often located near—but not directly in—the active site or at subunit interfaces, where they are inferred to enhance conformational flexibility required for the open-closed transition during catalysis [27].

- Evolutionary Preconditioning: The C3 to C4 transition was preceded by a period of increased Rubisco stability, creating the capacity to accept the necessary destabilizing mutations, followed by compensatory mutations that restored global stability [27].

Coordination of CCMs in Algal Systems

In aquatic environments where algae thrive, COâ‚‚ availability is limited, making CCMs essential for efficient photosynthesis. These mechanisms operate through complementary pathways:

- Biophysical CCMs: Rely on active transport of inorganic carbon (Ci) and the action of carbonic anhydrases (CAs) to concentrate COâ‚‚ near Rubisco [2].

- Biochemical CCMs: Similar to C4 photosynthesis in plants, they involve the fixation of Ci into C4 acid intermediates, which are later decarboxylated to release COâ‚‚ for Rubisco [2].

Recent studies demonstrate that these mechanisms operate jointly, with photorespiration remaining active even when CCMs are operational [7]. The relative contribution of each CCM type can shift based on environmental conditions, providing algae with metabolic plasticity [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: How can I determine the relative contributions of biophysical versus biochemical CCMs in my algal cultures?

- Challenge: Disentangling the simultaneous operation of multiple carbon fixation pathways.

- Solution: Use specific metabolic inhibitors in combination with measurements of photosynthetic output:

- Inhibit biophysical CCMs using ethoxyzolamide (EZ), a inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase activity [2].

- Inhibit biochemical CCMs using 3-mercaptopicolinic acid (MPA), a inhibitor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) [2].

- Monitor changes in photosynthetic rate (e.g., via Oâ‚‚ evolution) and cyclic electron flow around photosystem I to quantify compensatory effects [2].

- Interpretation: In Ulva prolifera, when the biochemical CCM is inhibited, the biophysical CCM can compensate for almost 100% of carbon fixation, whereas when the biophysical CCM is inhibited, the biochemical CCM contributes approximately 50% [2]. This indicates dominance of the biophysical CCM with biochemical support.

FAQ: Why does my Rubisco engineering strategy lead to unstable enzymes despite improved kinetics?

- Challenge: Directly introducing mutations to enhance turnover rate often compromises structural stability.

- Solution: Implement a two-stage evolution strategy inspired by natural evolutionary paths:

- First, introduce stabilizing mutations to create a "robustness reservoir" [27].

- Then, introduce functionally necessary but destabilizing mutations that enhance conformational flexibility and turnover [27].

- Finally, select for compensatory secondary mutations that restore global stability without sacrificing the gained activity [27].

FAQ: How do I account for photorespiration when studying CCMs in algae?

- Challenge: The assumption that active CCMs completely suppress photorespiration is incorrect.

- Solution: Actively monitor photorespiratory metabolites and recognize that CCM and photorespiratory genes can be co-induced.

- Monitor glycolate excretion, as it indicates photorespiratory activity and helps prevent toxic metabolite accumulation [7].

- Use mutants defective in specific photorespiratory components (e.g., the LCI20 chloroplast envelope transporter) to dissect the relationship between CCM and photorespiration [7].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Inhibitor-Based Dissection of CCM Contributions

This protocol determines the relative contributions of biophysical and biochemical CCMs by measuring photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution under specific inhibition.

Workflow: Assessing CCM Contributions with Inhibitors

Materials & Reagents:

- Algal Culture (e.g., Ulva prolifera, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii)

- Clark-type Oâ‚‚ Electrode System (e.g., Hansatech) [2]

- Inhibitors:

- Buffered Artificial Seawater: 20 mmol/L Hepes-NaOH, pH 8.0 [2]

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Cut algal samples into uniform fragments (e.g., 1-cm for macroalgae) and culture in natural seawater for >2 hours prior to measurement [2].

- Ci Depletion: Transfer fragments to buffered artificial seawater without Ci for 30 minutes to deplete endogenous carbon sources. Use seawater previously aerated at low pH with pure Nâ‚‚ to remove COâ‚‚ [2].

- Inhibitor Application: Add inhibitors to buffered artificial seawater containing 2 mmol/L NaHCO₃ in four treatment conditions:

- Control (no inhibitors)

- EZ only (50 µM)

- MPA only (1.5 mM)

- EZ + MPA combination

- Oâ‚‚ Evolution Measurement: Measure photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution rates at standardized conditions (e.g., 22°C, 200 μmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹) using an Oâ‚‚ electrode system [2].

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage inhibition for each pathway:

- % Biophysical CCM contribution = [1 - (Rate with EZ)/(Control rate)] × 100

- % Biochemical CCM contribution = [1 - (Rate with MPA)/(Control rate)] × 100

Protocol: Measuring Photosynthetic Rates via Oâ‚‚ Production

This general protocol measures photosynthetic rate under different experimental conditions using respirometers.

Materials & Reagents:

- Respirometers with calibrated pipettes [28]

- Aquatic Plants (e.g., Elodea species) [28]

- Sodium Bicarbonate Solution (NaHCO₃) as carbon source [28]

- Light Source with adjustable intensity (portable lights) [28]

- Photometer for measuring light intensity (μmol mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹) [28]

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Obtain a 5-6 inch aquatic plant shoot, cut the basal end, and place it cut-end-up in a test tube [28].

- Setup: Fill the tube with sodium bicarbonate solution, cap with a rubber stopper holding a curved pipette, and ensure the pipette end is submerged. Seal with Parafilm [28].

- Control Preparation: Prepare a second tube without a plant as a thermobarometer to account for temperature and pressure changes [28].

- Equilibration: Suspend tubes in a water-filled beaker to buffer temperature changes. Wait ten minutes for equilibrium before starting measurements [28].

- Measurement: Turn light on and record fluid position in pipettes every two minutes for at least ten minutes. Reset using syringes if needed [28].

- Data Correction: Subtract thermobarometer readings from plant readings to control for atmospheric changes [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Investigating Rubisco Trade-offs and CCM Coordination

| Reagent/Equipment | Specific Function | Example Application | Considerations & References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) | Inhibits carbonic anhydrase (CA), blocking biophysical CCM | Quantifying biophysical CCM contribution by measuring O₂ evolution reduction after application | Use at 50 µM; inhibits both extracellular and intracellular CA [2] |

| 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) | Inhibits phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), blocking biochemical CCM | Quantifying biochemical CCM contribution by measuring Oâ‚‚ evolution reduction after application | Use at 1.5 mM; specific to PEPCK-dependent C4 pathways [2] |

| Clark-type Oâ‚‚ Electrode | Measures photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution rates | Core instrument for quantifying photosynthetic output under different inhibitor treatments or conditions | Standardize light (200 μmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹) and temperature (22°C) [2] |

| LCI20 Mutant Strains | Defective in chloroplast glutamate/malate transporter | Studying link between photorespiration, metabolite transport, and CCM operation under very low COâ‚‚ | Available from CLiP collection; shows impaired growth during sudden COâ‚‚ limitation [7] |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) | Provides dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) for photosynthesis | Essential component in experimental media for maintaining carbon fixation in aquatic plants | Concentration should be optimized for specific organism; used in photosynthetic rate measurements [28] |

Data Presentation & Quantitative Analysis

Table 2: Quantitative Data on CCM Contributions from Inhibitor Studies in Ulva prolifera

| Experimental Condition | Photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ Evolution Rate | Inhibition Percentage | Compensatory Mechanism | Inferred Contribution to Carbon Fixation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No inhibitor) | Baseline rate (100%) | 0% | N/A | Baseline carbon fixation |

| EZ (CA Inhibitor) | ~50% of baseline | ~50% | Increase in biochemical CCM activity | Biophysical CCM contributes ~50% |

| MPA (PEPCK Inhibitor) | ~50% of baseline | ~50% | Increase in biophysical CCM activity | Biochemical CCM contributes ~50% |

| EZ + MPA (Both inhibitors) | Strongly reduced | >90% | Limited compensation possible | Combined CCMs account for majority of fixation |

Key Findings: The data demonstrates the functional complementarity between CCM types. When one CCM is inhibited, the other can partially compensate, maintaining approximately 50% of photosynthetic activity [2]. This plasticity is crucial for algal survival in fluctuating environments.

Advanced Technical Considerations

Interorganellar Communication in CCM Function

Emerging research highlights the importance of organelle coordination in CCM operation:

The diagram illustrates how the LCI20 transporter, located in the chloroplast envelope, facilitates a malate/glutamate exchange that connects chloroplast metabolism with mitochondrial photorespiratory processes [7]. This exchange may supply amino groups for mitochondrial conversion of glyoxylate to glycine during photorespiration [7]. Simultaneously, mitochondria may supply ATP to power plasma membrane bicarbonate transporters like HLA3, creating an integrated energy network supporting CCM operation [7].

Pyrenoid as a Metabolic Hub

Recent findings in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveal that the pyrenoid serves beyond its traditional role in CCM:

- Fatty Acid Biosynthesis Center: Subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) form phase-separated condensates at the pyrenoid periphery under COâ‚‚ limitation, linking carbon concentration to lipid metabolism [8].

- Metabolic Coordination: Pyrenoid-disrupted mutants show impaired fatty acid and triacylglycerol biosynthesis, supporting a model where CCMs supply carbon to FAS [8].

Advanced Methodologies for Investigating CCM Coordination: From Inhibitor Studies to Synthetic Biology

Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) are vital for efficient photosynthesis in algae, allowing them to overcome the slow diffusion of COâ‚‚ in water and the low affinity of Rubisco for COâ‚‚. Algae utilize two primary types of CCMs: biophysical CCMs, which actively transport and concentrate inorganic carbon (Ci) via carbonic anhydrases (CAs) and bicarbonate transporters, and biochemical CCMs (or C4-like pathways), which fix Ci into C4 organic acids before decarboxylation to supply COâ‚‚ to Rubisco [2]. Understanding the individual contribution of each mechanism is crucial for research on algal productivity, bloom dynamics, and bioengineering.

A powerful method to dissect these contributions involves the use of specific enzyme inhibitors. Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) inhibits carbonic anhydrase, thereby disrupting the biophysical CCM. Conversely, 3-Mercaptopicolinic acid (MPA) inhibits phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), a key enzyme in the biochemical CCM [2]. By applying these inhibitors separately and in combination, researchers can quantify the relative roles and compensatory interactions between these two carbon fixation pathways.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the specific functions of EZ and MPA in disrupting CCMs?

- EZ (Ethoxyzolamide): This cell-permeant inhibitor targets carbonic anhydrase (CA), both extracellular and intracellular [2]. CA catalyzes the interconversion between bicarbonate (HCO₃â») and COâ‚‚. By inhibiting CA, EZ disrupts the efficient conversion and transport of Ci forms, effectively impairing the biophysical CCM's ability to concentrate COâ‚‚ around Rubisco.

- MPA (3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid): This inhibitor specifically targets phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) [2]. In the biochemical CCM of some algae, PEPCK is responsible for the decarboxylation of C4 acids (like oxaloacetate) to release COâ‚‚. Inhibiting PEPCK thus blocks the function of the C4-like biochemical pathway.

Q2: During inhibitor experiments, carbon fixation declines but is not completely eliminated. Why?

This is a common observation and is indicative of the robust, complementary coordination between biophysical and biochemical CCMs. Research on Ulva prolifera has shown that when the biophysical CCM is inhibited by EZ, the biochemical CCM can be reinforced and compensate for approximately 50% of the total carbon fixation [2]. Conversely, when the biochemical CCM is inhibited by MPA, the biophysical CCM can compensate for nearly 100% of carbon fixation [2]. This plasticity ensures that the alga maintains a baseline level of photosynthetic activity.

Q3: How do I determine the optimal concentration of EZ and MPA for my algal species?

The optimal concentration can vary based on the algal species and experimental conditions. It is critical to perform a dose-response curve. The following table summarizes concentrations used successfully in a study on Ulva prolifera [2]:

| Inhibitor | Target Enzyme | Mechanism Disrupted | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZ (Ethoxyzolamide) | Carbonic Anhydrase (CA) | Biophysical CCM | 50 µM [2] |

| MPA (3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid) | Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase (PEPCK) | Biochemical CCM | 1.5 mM [2] |

Troubleshooting Tip: If you observe no effect, verify the solubility and stability of your inhibitor stock solutions. If the inhibition effect is too severe, try a lower concentration and ensure you are measuring photosynthesis parameters (e.g., Oâ‚‚ evolution) within a linear range.

Q4: What are the expected changes in photosynthetic parameters when these inhibitors are applied?

The expected changes, based on the mechanism of action, are as follows:

| Parameter | EZ Application (Biophysical CCM inhibited) | MPA Application (Biochemical CCM inhibited) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fixation Rate | Decreases [2] | Decreases [2] |

| Photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ Evolution | Decreases [2] | Decreases [2] |

| Compensatory CCM Activity | Biochemical CCM becomes more active [2] | Biophysical CCM becomes more active [2] |

| Cyclic Electron Flow (PSI) | Increases (supports reinforced biochemical CCM) [2] | May not show a significant change |

Q5: My results show unexpected activation of one CCM upon inhibition of the other. Is this normal?

Yes, this is a key finding and not an experimental error. The two CCMs are not independent but exist in a complementary coordination mechanism [2]. The inhibition of one pathway appears to trigger a compensatory upregulation of the other, a plasticity that allows the alga to maintain photosynthetic efficiency under fluctuating environmental conditions or chemical stress.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for assessing CCM contributions using inhibitors, showing the compensatory relationship between pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents essential for experiments designed to quantify CCM contributions using enzyme inhibition.

| Reagent | Function/Application in CCM Research |

|---|---|

| Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) | Cell-permeant inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase (CA); used to disrupt the biophysical CCM [2]. |

| 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) | Specific inhibitor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK); used to disrupt the biochemical (C4-like) CCM [2]. |

| Acetazolamide (AZ) | Specific inhibitor of external, periplasmic carbonic anhydrase; used to dissect internal vs. external CA activity [2]. |

| Buffered Artificial Seawater (e.g., with 20 mmol/L Hepes-NaOH, pH 8.0) | Provides a controlled ionic and pH environment for photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution measurements after Ci depletion [2]. |

| Clark-type Oâ‚‚ Electrode System | Standard apparatus for measuring rates of photosynthetic oxygen evolution as a proxy for carbon fixation efficiency [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing CCM Contributions via Inhibitors and Oâ‚‚ Evolution

This protocol is adapted from methods used in studies on Ulva prolifera [2].

Objective: To quantify the relative contributions of biophysical and biochemical CCMs to photosynthetic carbon fixation by applying specific enzyme inhibitors and measuring Oâ‚‚ evolution rates.

Materials:

- Healthy, axenic algal material.

- EZ inhibitor stock solution.

- MPA inhibitor stock solution.

- Buffered artificial seawater (e.g., 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0).

- Clark-type Oâ‚‚ electrode system.

- LED light source providing saturating quantum irradiance (e.g., 200 μmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut algal thalli into small, uniform fragments. Pre-culture them in natural seawater for several hours to ensure healthy metabolic activity.

- Ci Depletion: Transfer the fragments to Ci-free buffered artificial seawater. Bubble with pure Nâ‚‚ at low pH to remove dissolved COâ‚‚. Incubate for 30-60 minutes to deplete internal Ci pools.

- Inhibitor Incubation: Prepare experimental vials containing buffered artificial seawater with 2 mM NaHCO₃ as the Ci source.

- Control: No inhibitor added.

- +EZ: Add EZ to a final concentration of 50 µM.

- +MPA: Add MPA to a final concentration of 1.5 mM.

- (Optional) +EZ+MPA: Add both inhibitors to assess non-CCM background fixation. Equilibrate algal fragments in these inhibitor solutions for a predetermined time (e.g., 15-30 minutes) before measurement.

- Oâ‚‚ Evolution Measurement: Place the inhibitor-treated samples in the Oâ‚‚ electrode chamber. Measure the rate of photosynthetic Oâ‚‚ evolution under constant light and temperature.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage inhibition for each treatment:

% Inhibition = 100 × [1 - (Rate with Inhibitor / Rate without Inhibitor)]. - The inhibition by EZ reflects the contribution of the biophysical CCM.

- The inhibition by MPA reflects the contribution of the biochemical CCM.

- The compensatory effect is evidenced by the remaining activity in each single-inhibitor treatment.

- Calculate the percentage inhibition for each treatment:

Diagram 2: EZ and MPA inhibition targets in biophysical and biochemical CCM pathways.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

The quantitative data from inhibition experiments can be clearly summarized in a table for easy comparison and interpretation.

Table: Example Quantitative Contributions of CCMs in Ulva prolifera under Inhibitor Treatment [2]

| Experimental Condition | Impact on Carbon Fixation | Inferred CCM Contribution | Key Compensatory Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No Inhibitor) | 100% baseline activity | Both CCMs operational | N/A |

| + 50 µM EZ (Biophysical CCM inhibited) | ~50% reduction | Biophysical CCM contributes ~50% | Biochemical CCM activity increases; Cyclic electron flow around PSI is enhanced [2]. |

| + 1.5 mM MPA (Biochemical CCM inhibited) | ~0% reduction (fully compensated) | Biochemical CCM contribution is compensated | Biophysical CCM is reinforced, compensating for nearly 100% of total carbon fixation [2]. |

| Theoretical: EZ + MPA | Severe reduction (>90%) | Confirms both pathways are major Ci acquisition routes | Little to no compensation possible. |

Interpretation Guide:

- Dominant Pathway: In Ulva prolifera, the biophysical CCM is the dominant pathway under standard conditions, as its inhibition leads to a direct and significant drop in carbon fixation.

- Supporting Role: The biochemical CCM plays a crucial supporting role, providing functional redundancy and resilience.

- Plasticity: The ability of one CCM to upregulate upon inhibition of the other highlights a sophisticated regulatory network for maintaining photosynthetic performance. This coordination is a key target for optimizing algal growth in both natural and biotechnological contexts.

Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) are essential biological systems that enhance photosynthetic efficiency by elevating the concentration of COâ‚‚ around the carbon-fixing enzyme RuBisCO. In algal systems, two primary CCM types exist: biophysical CCMs, which rely on inorganic carbon transport and conversion, and biochemical CCMs, which utilize organic carbon intermediates in C4-like pathways [2]. Understanding the coordination between these mechanisms requires metabolomic tracing, a powerful technique that uses stable isotope tracers to track carbon flux through metabolic pathways, providing dynamic insights into pathway activities [29] [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between metabolomics and metabolic tracing? Metabolomics provides a static snapshot of metabolite concentrations at a single point in time, showing what metabolites are present and their relative amounts. In contrast, metabolic tracing uses stable isotope labels to track how metabolites move through pathways over time, revealing the dynamic flow of carbon and the actual activity of metabolic pathways. While metabolomics might show that a metabolite pool has increased, only tracing can determine if this is due to increased production or decreased consumption [30].

Q2: Why is understanding both biophysical and biochemical CCMs important in algae research? Research on Ulva prolifera has demonstrated that these two CCM types function complementarily. When the biophysical CCM is inhibited, the biochemical CCM can compensate for approximately 50% of carbon fixation. Conversely, the biophysical CCM can compensate for nearly 100% of fixation when the biochemical CCM is inhibited. This plasticity allows algae to maintain efficient photosynthesis under varying environmental conditions [2].

Q3: What are the key advantages of stable isotopes over radioactive tracers? Stable isotopes (such as ¹³C, ¹âµN, ²H) are non-radioactive, making them safer to handle without special precautions. They allow parallel measurement of label incorporation into many downstream metabolites simultaneously using mass spectrometry or NMR. Modern instruments can detect these isotopes with high sensitivity, enabling comprehensive tracking through multiple pathways [29] [30].

Q4: What common issues affect labeling patterns in tracer experiments? Several factors can confound interpretation: insufficient tracer exposure time for slow-turnover pathways, failure to account for tracer dilution from endogenous sources, loss of labeled atoms as COâ‚‚ in decarboxylation reactions, and metabolic cross-talk between parallel pathways that can obscure the original tracer source [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Label Detection or Low Signal Intensity

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak isotope signal | Tracer concentration too low | Optimize tracer dose through pilot experiments; ensure it doesn't disturb endogenous physiology [30] |

| Incomplete labeling | Incorrect exposure time for pathway kinetics | Extend labeling time for slower processes (e.g., protein synthesis vs. glycolytic lactate production) [30] |

| High variability between replicates | Inconsistent sample preparation or quenching | Standardize metabolite extraction protocols; use rapid quenching methods to halt metabolism instantly [29] |

| Carryover between samples | Contaminated LC-MS system | Include blank runs (mobile phase only) and solvent injections between samples to identify and reduce carryover [31] |

Data Quality and Interpretation Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Batch effects in large studies | Instrument drift across multiple batches | Use quality control (QC) samples from a pooled mixture of all samples; apply intra- and inter-batch normalization algorithms [31] |

| Misidentification of labeled peaks | Inaccurate isotopologue extraction | Use targeted extraction tools like MetTracer that generate theoretical m/z values for all possible isotopologues [32] |

| Inconsistent pathway interpretation | Natural isotope abundance not accounted for | Apply appropriate correction algorithms for natural abundance of ¹³C, ²H, ¹âµN, etc., before flux interpretation [29] |

| Unknown peaks in data | Limited metabolite database coverage | Use untargeted approaches with MS/MS spectral matching against public databases; report unknown compounds per Metabolomics Standards Initiative [33] |

Experimental Design Challenges

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unclear coordination between CCMs | Difficulty isolating mechanisms | Use specific inhibitors: EZ (ethoxyzolamide) for CA in biophysical CCMs; MPA (3-mercaptopicolinic acid) for PEPCK in biochemical CCMs [2] |

| Inability to distinguish nutrient sources | Single tracer limitations | Use multiple tracers simultaneously (e.g., [U-¹³C]-glucose, [U-¹³C]-glutamine, [U-¹³C]-acetate) with different labeling patterns [32] |

| Low coverage of labeled metabolites | Limited analytical scope | Implement global tracing technologies like MetTracer that combine untargeted metabolomics with targeted extraction for metabolome-wide coverage [32] |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Distinguishing Biophysical vs. Biochemical CCM Contributions

Purpose: Quantify the relative contributions of biophysical and biochemical CCMs to carbon fixation in algal systems [2].

Reagents and Materials:

- Ethoxyzolamide (EZ): Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor targeting biophysical CCM

- 3-mercaptopicolinic acid (MPA): PEPCK inhibitor targeting biochemical CCM

- Buffered artificial seawater (20 mmol/L Hepes-NaOH, pH 8.0)

- Clark-type Oâ‚‚ electrode system

- ¹³C-labeled bicarbonate or CO₂ source

Procedure:

- Prepare axenic cultures of algal species (e.g., Ulva prolifera).

- Divide cultures into four treatment groups: control, EZ-only (50 µM), MPA-only (1.5 mM), and EZ+MPA combination.

- Deplete endogenous carbon sources by incubating samples in Ci-free buffered seawater for 30 minutes.

- Add inhibitors to respective treatments 15 minutes before isotopic measurements.

- Introduce ¹³C-labeled carbon source (e.g., NaH¹³CO₃) simultaneously with photosynthetic O₂ evolution measurements.

- Terminate experiments at timed intervals (30, 60, 120 minutes) for metabolomic analysis.

- Quantify ¹³C incorporation into metabolites using LC-MS and calculate relative contributions of each CCM.

Protocol: Global Isotope Tracing with MetTracer

Purpose: Achieve comprehensive tracking of isotope labeling across the metabolome [32].

Workflow:

Critical Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Rapidly quench metabolism (liquid Nâ‚‚), extract metabolites with methanol:ethanol (1:1 v/v) containing internal standards.

- LC-MS Analysis: Use reverse-phase chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometer (Q-TOF or Orbitrap).

- Metabolite Annotation: Match MS2 spectra against standard libraries (e.g., HMDB, MassBank).

- Targeted Extraction: Generate theoretical m/z values for all possible isotopologues from annotated metabolites.

- Quantification: Extract and quantify isotopologue peaks, applying natural abundance correction.

- Pathway Mapping: Calculate labeling extents and patterns across metabolic pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Tracing in Algal CCM Research

| Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-¹³C]glucose | Tracing glycolysis vs. PPP | Distinguishes oxidative PPP (M+1 lactate) from glycolysis (M+2 lactate) [29] |

| [U-¹³C]glutamine | Tracing TCA cycle & reductive carboxylation | Detects "backwards" TCA flux via M+5 citrate formation [29] |

| Ethoxyzolamide (EZ) | Inhibits carbonic anhydrase | Suppresses biophysical CCM by blocking HCO₃â»/COâ‚‚ interconversion [2] |

| 3-Mercaptopicolinic Acid (MPA) | Inhibits PEPCK | Suppresses biochemical CCM by blocking C4 acid decarboxylation [2] |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Quality control & normalization | Monitors instrument performance; corrects technical variation [31] |

| ¹³C-bicarbonate (NaH¹³CO₃) | Direct carbon fixation tracing | Tracks inorganic carbon incorporation into metabolites [2] |

Data Analysis Pathway

Implementation Tools:

- XCMS, MZmine3: For peak detection and alignment [33]

- MetTracer, X13CMS: For isotopologue extraction and quantification [32]

- geoRge, mzMatch: For data normalization and batch effect correction [31] [33]

- PathVisio, MetaboAnalyst: For pathway mapping and visualization [33]

Advanced Applications: System-Wide Metabolic Coordination Analysis