Optimizing Synthetic Microbial Communities: From Foundational Ecology to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize the function of Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs).

Optimizing Synthetic Microbial Communities: From Foundational Ecology to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize the function of Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs). It explores the foundational ecological principles governing microbial interactions, details cutting-edge design and assembly methodologies from bottom-up to data-driven approaches, and addresses critical challenges in stability and predictability. The content further outlines advanced validation frameworks, including metabolic modeling and gnotobiotic models, for rigorous functional assessment. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this review aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to harness SynComs for transformative applications in biomedicine and therapeutic development.

The Ecological Foundation of Synthetic Microbial Communities

Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) are custom-designed groups of microorganisms intentionally assembled to mimic or enhance natural microbial communities. They are used as tractable model systems to study complex biological interactions and to provide tailored functions for agricultural, environmental, and biomedical applications [1] [2]. These consortia can range from simple combinations of a few strains to complex assemblages of over a hundred members, designed to replicate key functional attributes of natural ecosystems [3] [4].

The core premise behind SynComs is to reduce the overwhelming complexity of natural microbiomes into simpler, well-defined systems that are more amenable to experimental manipulation and mechanistic study. This approach enables researchers to move beyond correlative observations toward causal understanding of microbial interactions and their impacts on host organisms or environments [3] [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What fundamentally distinguishes a SynCom from a single-strain inoculant? While single-strain inoculants consist of one microbial strain targeting a specific function, SynComs are multi-strain consortia designed to capture emergent properties and ecological resilience through microbial interactions. Single-strain approaches often fail to persist in complex environments due to limited functional capacity and inability to form stable ecological networks. In contrast, SynComs leverage division of labor, cross-feeding relationships, and niche complementarity to achieve more stable and robust functionality [1] [4].

FAQ 2: Why does my carefully designed SynCom fail to establish in the target environment? SynCom failure commonly results from inadequate environmental adaptation or disruption by resident microbiota. Even functionally optimized strains may lack necessary traits for persistence in specific environmental conditions like pH, temperature, or nutrient availability. The established native microbiome can also resist invasion through resource competition or direct antagonism. To mitigate this, incorporate environmental preconditioning of strains and include "helper" species that facilitate community integration through metabolic support or protection against competitors [1] [4].

FAQ 3: How do I balance functional precision with ecological stability in SynCom design? Achieving both functional precision and ecological stability requires strategic integration of ecological principles. Incorporate a mix of generalists and specialists to maintain function under fluctuating conditions, and design cross-feeding networks that create interdependent relationships stabilizing the community. Include keystone species that provide structural integrity to the community through habitat modification or facilitation of other members. Implement metabolic modeling to identify potential competitive bottlenecks before experimental validation [1].

FAQ 4: What is the optimal number of strains for a SynCom? SynCom size should be determined by functional requirements rather than arbitrary targets. Research shows successful SynComs range from 3-119 members, with many effective communities containing approximately 13 members on average. The optimal size depends on the complexity of the target function and the stability requirements of the system. Overly simplified consortia risk losing keystone species, while excessively complex communities become difficult to control and reproduce [3] [1].

FAQ 5: How can I predict and prevent cheater strains from undermining my SynCom? Cheater strains that exploit community resources without functional contribution can be minimized through several strategies. Implement spatial structuring in your cultivation system to create microenvironments that alter quorum sensing dynamics and public goods distribution. Design resource utilization patterns that make cooperation evolutionarily stable, and include evolution-guided selection to identify strains with reduced cheating propensity over multiple generations [1].

Comparative Analysis of SynCom Design Approaches

Table 1: Key Approaches for SynCom Design and Construction

| Approach | Methodology | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Function-Based Selection | Selects strains encoding key functions identified through metagenomic analysis; uses metabolic modeling to predict cooperative potential [3] | Building communities for specific functional outputs; modeling disease-associated microbiomes; applications requiring precise metabolic capabilities | May overlook taxonomic representatives that support community stability; requires extensive genomic data and computational resources |

| Top-Down Approach | Starts with complex natural communities and simplifies through culturing and serial dilution; preserves ecological structure [2] | Studying community assembly rules; applications where maintaining natural relationships is priority | Often excludes unculturable members; may retain unnecessary complexity for targeted applications |

| Bottom-Up Approach | Assembling individual strains with well-characterized beneficial functions; "function-first" strategy [2] | Testing specific ecological hypotheses; precision applications with defined mechanisms | May miss emergent properties of more complex systems; requires extensive pre-characterization of individual strains |

| Integrated Approach | Combines microbiome sequencing data with isolate characterization; considers both abundance and functional significance [2] | Developing robust agricultural inoculants; bridging fundamental research with applied outcomes | More resource-intensive; requires expertise in both computational and experimental methods |

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for SynCom Performance Evaluation

| Performance Category | Specific Metrics | Measurement Methods | Target Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Output | Metabolite production, pathogen suppression, nutrient solubilization | HPLC/MS, pathogen growth assays, elemental analysis | Application-dependent; compared to positive controls |

| Community Stability | Strain persistence, resistance to invasion, functional resilience | Strain-specific qPCR, community profiling, perturbation response | >70% original members maintained over relevant timeframe |

| Host Impact | Plant biomass, disease symptoms, animal pathophysiology | Biomass measurement, disease scoring, histological analysis | Statistically significant improvement vs. controls |

| Environmental Resilience | Performance across conditions, survival under stress | Multi-environment testing, stress challenge experiments | Consistent function across relevant environmental variations |

Experimental Protocols for SynCom Development

Protocol 1: Function-Based SynCom Design from Metagenomic Data

This protocol enables design of SynComs based on functional profiling of metagenomic samples, prioritizing key ecosystem functions over taxonomic representation [3].

Materials Required:

- Metagenomic sequences from target environment

- Reference genome collection of isolated strains

- Computing infrastructure with ≥16GB RAM

- Pfam database for functional annotation

- GapSeq software for metabolic modeling

- BacArena toolkit for community simulation

Methodology:

- Metagenomic Annotation: Process metagenomic assemblies through Prodigal for protein prediction and hmmscan against Pfam database to identify encoded functions

- Function Vectorization: Create binarized Pfam vectors for both metagenomes and candidate genomes using MiMiC2-butler.py script

- Function Weighting: Assign additional weights to core functions (>50% prevalence) and differentially enriched functions (Fisher's exact test, p<0.05)

- Strain Selection: Iteratively select highest-scoring genomes based on functional matches to metagenomic profiles, using weighted scoring that prioritizes key functions

- Metabolic Validation: Generate genome-scale metabolic models using GapSeq and simulate cooperative growth in BacArena over 7-hour simulations

Troubleshooting Tip: If selected strains show poor coexistence in validation, adjust function weightings using MiMiC2-weight-estimation.py to identify optimal balance between functional coverage and community compatibility.

Protocol 2: Ecological Interaction Screening for Community Stability

This protocol assesses pairwise interactions between potential SynCom members to identify combinations that promote stable coexistence [1].

Materials Required:

- Pure cultures of candidate strains

- Appropriate growth media and microplate readers

- Metabolite analysis capability (HPLC, GC-MS)

- Automated cultivation systems (optional)

Methodology:

- Pairwise Interaction Screening: Co-culture all possible strain pairs in microplates, monitoring growth kinetics and final biomass compared to mono-cultures

- Metabolic Profiling: Analyze spent media for cross-feeding metabolites (organic acids, amino acids, vitamins)

- Antagonism Assessment: Screen for inhibitory interactions using agar overlay and spent media transfer assays

- Network Mapping: Construct interaction network with edges representing significant positive/negative interactions

- Module Identification: Identify clusters of strains with predominantly cooperative interactions for SynCom assembly

Troubleshooting Tip: If widespread antagonism prevents community assembly, consider spatial segregation in the delivery system or sequential inoculation of compatible subgroups.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SynCom Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Analysis Tools | MEGAHIT, Prodigal, hmmscan, Pfam database | Assembly, gene prediction, and functional annotation of complex microbial communities [3] |

| Metabolic Modeling Software | GapSeq, BacArena, Virtual Colon | Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and simulation of community interactions [3] |

| Culture Collections | HiBC, miBC2, PiBAC, Hungate1000 | Source of validated, genome-sequenced microbial isolates for consortium assembly [3] |

| SynCom Design Algorithms | MiMiC2 pipeline | Automated selection of community members based on functional profiling [3] |

| Interaction Screening Platforms | Microplate co-culture systems, spent media assays | High-throughput assessment of microbial interactions [1] |

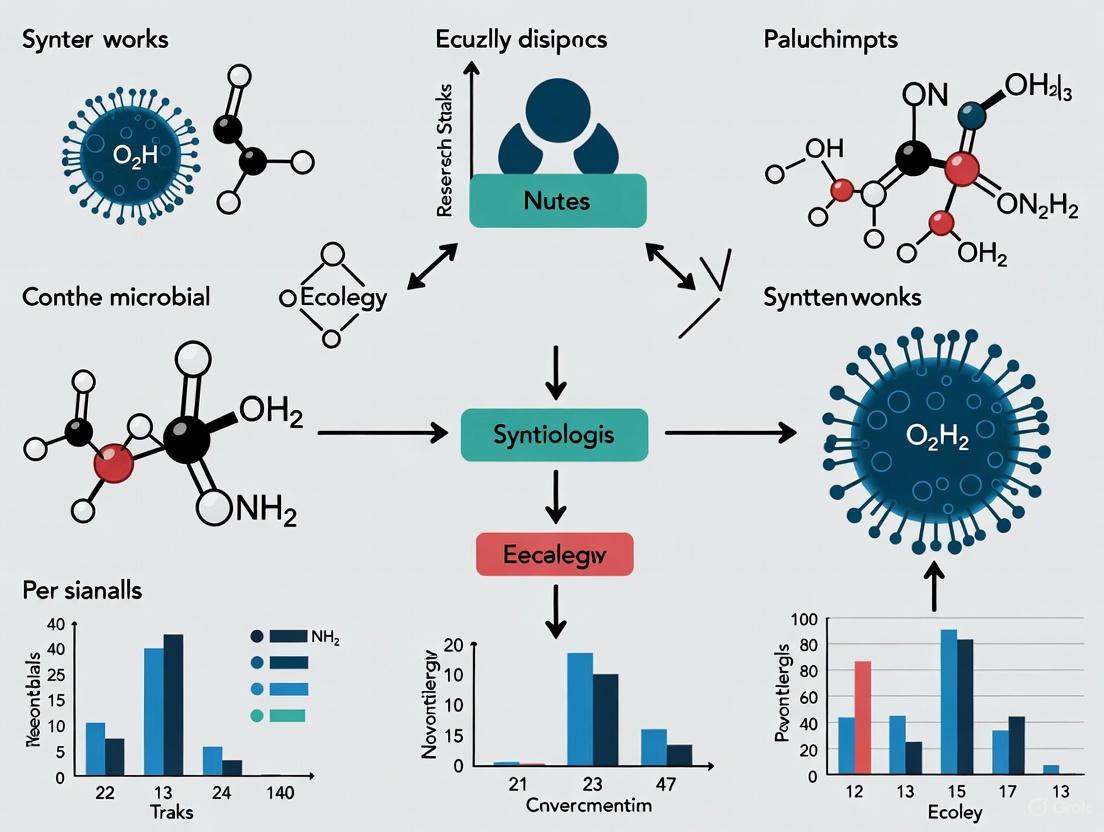

Workflow Visualization

Function-Based SynCom Design Workflow

Ecological Principles for Stable SynCom Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is my synthetic microbial community unstable, and how can I improve its stability?

Instability often arises from uncontrolled competition, cheater exploitation, or unaccounted for higher-order interactions. To improve stability, consider spatial structuring like using porous solid supports in bioreactors to limit cheater access to public goods [6]. You can also engineer obligate mutualisms where each member depends on the other for an essential metabolite, creating evolutionary coupling [7]. Furthermore, analyze your system for potential three- and four-way interactions, as these can dramatically alter community dynamics and impose both lower and upper bounds on stable diversity [8].

FAQ 2: My community does not perform the intended function, even with the correct species. What could be wrong?

The issue likely lies in the environmental context or interaction variability. Environmental factors like pH can fundamentally shift interactions from mutualism to parasitism [6] [9]. First, re-check the environmental conditions (pH, nutrient ratios, temperature) to ensure they align with the functional goals. Second, measure interaction strengths under your specific experimental conditions, as they are not fixed but highly variable. A cooperation optimized at a 1:1 strain ratio may fail at a 10:1 ratio due to the stoichiometry of required subunits [9].

FAQ 3: How can I effectively incorporate Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) into my community design and models?

Start with a bottom-up approach using a few well-characterized species [7] [9]. To identify HOIs, look for deviations from predictions made by models that only include pairwise interactions [10]. When modeling, use frameworks that can capture non-additive effects, where the presence of a third species modifies the interaction between two others [10] [8]. Mechanistic models, parameterized with empirical data, can help reveal how HOIs emerge from underlying biological processes [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Cheater Strains Exploiting Cooperative Members

Background & Diagnosis: Cheaters avoid the metabolic cost of producing public goods (e.g., enzymes, siderophores) but still consume them, leading to a "tragedy of the commons" and community collapse [6]. This is diagnosed by a decline in community function alongside an increasing proportion of non-producer strains.

Solution Steps:

- Implement Spatial Structure: Culture communities in biofilms or on agar instead of well-mixed flasks. Spatial structure allows cooperator clusters to form, limiting cheater access to public goods and providing a local fitness advantage to producers [6].

- Engineer Metabolic Interdependence: Create a system where the cheater strain depends on the cooperator for an essential nutrient. For example, use auxotrophic strains in a cross-feeding mutualism where each strain supplies an essential amino acid or vitamin to the other [7] [6].

- Link Function to Essential Genes: Use synthetic biology to couple the production of the public good to the expression of a gene essential for survival under your culture conditions.

Problem: Unpredicted Community Collapse or Species Loss

Background & Diagnosis: Theoretical models predict that random pairwise interactions create an upper bound on diversity—more species lead to less stability [8]. However, higher-order interactions can create a lower bound, making small communities sensitive to species removal. Collapse can occur if diversity falls outside this stable window.

Solution Steps:

- Diagnose Interaction Types: Determine if collapse is due to overly strong pairwise competition or the loss of a species that was mediating a critical HOI.

- Modulate Interaction Strength: If strong pairwise competition is the issue, reduce its strength by providing more abundant or diverse nutrient sources to lessen resource overlap.

- Optimize Diversity: Use the table below to understand how different interaction types scale with community size (N). Aim for a diversity level that balances these forces.

Table: Scaling of Community Sensitivity with Number of Species (N)

| Interaction Order | Scaling of Sensitivity with N | Impact on Diversity |

|---|---|---|

| Pairwise | Decreases as ~1/N [8] | Imposes an Upper Bound |

| Three-Way (HOI) | Independent of N [8] | Regulates dynamics without a strong diversity bound |

| Four-Way (HOI) | Increases with ~N [8] | Imposes a Lower Bound |

Problem: High Variability in Community Function Across Replicates

Background & Diagnosis: Interaction strengths are not fixed but are highly variable and context-dependent [9]. This variability can stem from slight differences in initial species ratios, local environmental fluctuations (e.g., pH gradients), or stochasticity in gene expression.

Solution Steps:

- Quantify Interaction Variability: Systematically measure the strength of key interactions (e.g., cooperation, inhibition) across a range of relevant conditions and species ratios, as demonstrated in lactococcal bacteriocin systems [9].

- Standardize Inoculum Ratios: Carefully control the initial starting ratios of community members, as functional outputs like antibiotic production are often highly sensitive to founding proportions [9].

- Incorporate Variability into Models: Move beyond models with fixed interaction coefficients. Use modeling frameworks that explicitly incorporate the measured variability of interactions, which dramatically improves the predictive power of bottom-up forecasts [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Quantifying Cooperation and its Variability

Objective: To measure the strength of a cooperative interaction (e.g., joint antibiotic production) and how it varies with the ratio of cooperating strains [9].

Materials:

- Two engineered cooperating strains (e.g., Lactococcus lactis Cα and Cβ, which jointly produce bacteriocin lcnG) [9].

- Appropriate growth medium (e.g., GM17 for L. lactis).

- Soft agar for lawn plates.

- A reporter strain sensitive to the cooperative antibiotic.

Methodology:

- Prepare Supernatants: Grow monocultures of Cα and Cβ to stationary phase. Mix their supernatants in a series of ratios (e.g., 30:1, 10:1, 1:1, 1:10, 1:30), keeping the total volume constant.

- Create Lawn Plates: Seed soft agar with the antibiotic-sensitive reporter strain and pour into plates.

- Inhibition Assay: Place a fixed volume of each supernatant mix into a well on the lawn plate. Incubate the plates at the optimal temperature for 8-24 hours.

- Quantify Cooperation: Measure the diameter of the inhibition zone around each well. The zone size is a proxy for the strength of cooperation (lcnG production). The function will typically be maximized at a specific ratio (often 1:1) and decline as the ratio becomes unbalanced [9].

Workflow for Quantifying Cooperative Variability

Protocol 2: Detecting Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs)

Objective: To determine if the interaction between two species is modified by the presence of a third species [10].

Materials:

- Three microbial strains (A, B, C).

- Standard culture equipment and medium.

Methodology:

- Design Co-cultures: Set up four culture conditions:

- Monocultures of A, B, and C.

- Pairwise co-cultures: A+B, A+C, B+C.

- The full three-species community: A+B+C.

- Measure Growth: For each condition, measure the population density of each species at stationary phase or track growth kinetics.

- Calculate Expected Abundance: Use an additive null model (e.g., the Generalized Lotka-Volterra model parameterized from mono- and pairwise cultures) to predict the abundance of each species in the three-member community.

- Identify HOI: Statistically compare the observed abundances in the three-species community with the model predictions. A significant deviation indicates the presence of a higher-order interaction [10].

Table: Example Data Structure for HOI Detection

| Culture Condition | Observed Abundance of Species A (OD600) | Predicted Abundance of Species A (OD600) | Deviation (HOI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (monoculture) | 1.0 ± 0.1 | (Baseline) | - |

| A + B | 0.7 ± 0.05 | (From model) | - |

| A + C | 1.2 ± 0.1 | (From model) | - |

| A + B + C | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.75 (predicted from pairs) | Significant (p < 0.05) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Synthetic Microbial Ecology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains | Genetically engineered strains unable to synthesize a specific essential metabolite (e.g., an amino acid or vitamin). | Constructing obligate cross-feeding mutualisms for stable consortia [6]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Genes like GFP, mCherry, etc., constitutively expressed in different strains. | Enabling real-time, species-specific quantification of population dynamics in co-cultures [9]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico models of an organism's metabolism. | Predicting potential metabolic interactions, competition, and cross-feeding opportunities between community members [11]. |

| Sensitive Reporter Strain | A strain that is susceptible to an antibiotic or bacteriocin produced by the synthetic community. | Quantifying the functional output of a cooperative behavior (e.g., joint antibiotic production) [9]. |

| ArnicolideC | ArnicolideC, MF:C19H26O5, MW:334.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderic acid I | Ganoderic acid I, MF:C30H44O8, MW:532.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Environmental Context-Dependency in SynCom Research

FAQ 1: Why does my synthetic community (SynCom) perform well in vitro but fail to establish or function in vivo or in field conditions?

This is a common challenge often resulting from a failure to account for the full complexity of the target environment. A SynCom designed in the controlled, stable conditions of a laboratory may not be resilient enough to compete with native microbes or withstand fluctuating environmental stresses like pH shifts or nutrient competition [4]. The laboratory environment does not replicate the dynamic physical and chemical pressures of a natural habitat, such as the rhizosphere or gut. Furthermore, the resident microbiome can outcompete introduced SynCom members for resources and space if they are not selected for their adaptability [12] [13]. To mitigate this, the design process should incorporate evolution-guided selection, where SynComs are pre-adapted under controlled stress conditions (e.g., gradual temperature increases or resource limitation) to enhance their fitness and stability in the target environment [14].

FAQ 2: How do abiotic factors like pH and temperature directly influence the stability of my defined consortium?

Abiotic factors are fundamental drivers of microbial metabolism, interactions, and survival. They can create niche differentiation that either promotes stable coexistence or leads to the collapse of the community [7].

- pH directly affects enzyme activity and nutrient solubility. Shifts in pH can alter the outcome of microbial interactions, turning a neutral relationship into a competitive one if species have different pH optimums for the same resource.

- Temperature influences reaction rates and membrane fluidity. Fluctuations can disrupt synchronized metabolic processes in a division-of-labor SynCom, leading to a buildup of toxic intermediates or a failure to produce a key final product.

- Oxygen Availability determines the types of metabolic pathways that are energetically favorable. The presence of aerobic and anaerobic microniches can be a critical design consideration for ensuring the survival of all constituent members [7].

FAQ 3: What is the role of the "environmental filter" in SynCom assembly and persistence?

The environmental filter is a concept from ecology that describes how the physical and chemical conditions of a habitat selectively determine which species can persist there [14]. Even a SynCom with perfectly engineered in vitro interactions will not establish if its members cannot survive the environmental conditions of the target site. These conditions—such as osmolality in the gut, or UV exposure and desiccation on a leaf surface (phyllosphere)—act as a filter, preventing non-adapted strains from colonizing. A successful design must therefore select strains that can pass through this filter, meaning they are pre-adapted to the salient stresses of the deployment environment [13] [14].

FAQ 4: How can I pre-adapt my SynCom to a specific environmental stress, such as a high salinity soil or an inflamed gut?

Pre-adaptation involves using experimental evolution to guide your SynCom toward greater resilience.

- Identify Key Stresses: Characterize the target environment to define the major stressor (e.g., salt concentration, bile acids, low pH).

- Directed Evolution: Serially passage your SynCom under gradually increasing levels of the stressor in a bioreactor or chemostat.

- Selection Pressure: Maintain the selective pressure over multiple generations, allowing for the enrichment of mutants or sub-strains with enhanced tolerance.

- Characterization: Re-isolate and sequence evolved strains to understand the genetic basis of adaptation and re-assemble the improved SynCom [15] [14]. This process actively selects for communities that are not just functionally defined but also ecologically robust.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SynCom Environmental Failures

| Observed Problem | Potential Environmental Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Colonization & Persistence | Environmental filtering (e.g., wrong pH, temperature); competition from resident microbiota. | Isolate strains from the target environment; use evolution-guided selection for pre-adaptation [14]; include keystone species from the native microbiome [12]. |

| Loss of Community Function | Abiotic stress disrupts metabolic interactions; breakdown of cross-feeding dependencies. | Engineer functional redundancy; design communities with modular metabolic stratification to buffer against perturbations [14]. |

| Unstable Community Composition | Dynamic environmental conditions cause boom-bust cycles for different members. | Engineer ecological interactions by balancing cooperative and competitive relationships to maintain dynamic equilibrium [14]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Labs | Minor variations in growth media, temperature control, or inoculation protocols. | Standardize and meticulously document all culturing and assembly protocols; use gnotobiotic systems for initial validation [16] [15]. |

Table 2: Key Environmental Parameters to Monitor in Different Contexts

| Application Context | Critical Physical Parameters | Critical Chemical Parameters | Recommended Reagents for Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gut/Medical (LBP) | Temperature (37°C), Anaerobic conditions, Fluid flow & shear stress. | pH gradient, Bile salts, Digestive enzymes, Oxygen concentration. | Anaerobic chamber, Bile salts (e.g., Oxgall), Pancreatin, pH-stable buffers. |

| Rhizosphere/Agriculture | Soil porosity, Water potential, Temperature flux, Root exudate flow. | pH, Root exudates (specific sugars, organic acids), Nutrient gradients (N, P, K). | Plant agar, Hoagland's solution, Specific carbon sources (e.g., malic acid). |

| Bioremediation | Temperature, Mixing/Oxygen transfer, Contaminant bioavailability. | pH, Contaminant concentration, Electron acceptors (O2, NO3-), Salinity. | Defined mineral salts media, Target pollutant (e.g., phenol), Redox indicators. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SynCom Environmental Research

| Item | Function/Application in SynCom Research |

|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Systems (e.g., germ-free mice) | Provides a sterile living host for testing SynCom establishment and function in the absence of confounding environmental variables from a native microbiome [16] [15]. |

| Chemostats/Bioreactors | Enables continuous culture for maintaining stable environmental conditions (pH, temperature, nutrient levels) and for performing experimental evolution and pre-adaptation studies [7]. |

| Anaerobe Chamber | Creates an oxygen-free atmosphere essential for cultivating and manipulating strict anaerobic species common in gut and soil SynComs [16]. |

| Defined Minimal Media | Allows precise control over the chemical environment and nutrient availability, forcing synergistic interactions and making outcomes more interpretable and reproducible [7]. |

| High-Throughput Culturing Platforms | Facilitates the rapid screening of hundreds of microbial isolates and community combinations under different environmental conditions to identify optimal assemblages [14]. |

| Biosensors (e.g., GFP, Luciferase) | Genetically engineered reporters that allow real-time monitoring of gene expression, metabolic activity, and spatial localization of SynCom members in response to environmental changes [15]. |

| Hymexelsin | Hymexelsin, MF:C21H26O13, MW:486.4 g/mol |

| Linderanine C | Linderanine C, MF:C15H16O5, MW:276.28 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing SynCom Resilience to Abiotic Stressors

Objective: To evaluate the stability and functional output of a SynCom under a gradient of a specific environmental stressor (e.g., pH, salinity, temperature).

- SynCom Cultivation: Grow the defined SynCom to mid-exponential phase in an appropriate defined medium under standard conditions.

- Stress Gradient Setup: Prepare a multi-well plate or series of flasks with media titrated to create a gradient of the stressor (e.g., pH from 5.0 to 8.0 in 0.5 increments; NaCl from 0mM to 500mM).

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate each condition with a standardized inoculum of the SynCom. Incubate under static or shaking conditions with controlled temperature.

- Monitoring:

- Growth Kinetics: Use optical density (OD600) measurements to track population dynamics over 24-72 hours.

- Compositional Stability: At endpoint, plate communities on selective media or use 16S rRNA gene sequencing to quantify the relative abundance of each member.

- Functional Output: Measure the concentration of a key functional metabolite (e.g., a plant hormone, antibiotic, or detoxification product) using HPLC or ELISA.

- Data Analysis: Determine the range of the stressor over which the community maintains stable composition and target function [7] [12].

Protocol 2: Pre-adapting a SynCom via Experimental Evolution

Objective: To enhance the fitness and resilience of a SynCom for a specific challenging environment.

- Base Community: Start with your well-characterized, defined SynCom.

- Selection Environment: Establish a chemostat or use serial batch culture in a medium that mimics the key stressor of the target environment (e.g., high bile salts for gut applications, low phosphorus for soil).

- Evolutionary Passaging: Serially transfer the community into fresh selective medium at a fixed dilution and time interval (e.g., 1:100 every 48 hours). This maintains a constant selective pressure.

- Monitoring Evolution: Periodically sample the evolving community to:

- Track changes in fitness (growth rate/yield) under the selective condition.

- Monitor community composition via sequencing.

- Isolation and Characterization: After dozens of generations, isolate the evolved community and individual strains. Sequence evolved isolates to identify mutations. Re-constitute the SynCom with evolved members and test its performance against the ancestral community in the target environment model [15] [14].

Visualizing Environmental Influence on SynCom Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of how the physical and chemical environment acts as a filter and a driver of dynamics in synthetic microbial communities.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common experimental challenges in synthetic microbial community (SynCom) research, providing solutions grounded in ecological principles.

FAQ 1: Why does my SynCom fail to persist or function consistently when introduced into a natural environment (e.g., soil or a host)?

- Problem: A synthetic community that is stable in vitro shows poor survival or functional redundancy in situ.

- Solution & Rationale:

- Challenge from Resident Microbes: The native microbiome competes with your SynCom. One study showed that a 6-member Pseudomonas SynCom exhibited reduced growth and a significant increase in dead cells (up to 81%) when exposed to native soil microbes [17].

- Mitigation Strategy: Screen for "persistent" strains. These persistent strains may employ survival strategies like metabolic down-regulation or dormancy. Incorporating such strains, identified through co-culture assays with native communities, can enhance SynCom resilience [17].

- Pre-Validation: Before large-scale application, test SynCom stability in a system that allows chemical interaction with the native microbiome (e.g., a transwell system) without physical contact, to pre-screen for competitive exclusion [17].

FAQ 2: How do I select the right microbial members for a functionally stable SynCom?

- Problem: The designed community is unstable, or members fail to cooperate, leading to loss of function.

- Solution & Rationale: Member selection should be guided by more than just taxonomy. The following integrated strategies are recommended:

- Top-Down Approach: Start with a complex natural community from a high-performing environment (e.g., disease-suppressive soil) and progressively simplify it to identify a core, functional group [16] [11].

- Bottom-Up Approach: Assemble individual strains with known, complementary functional traits (e.g., nutrient solubilization, pathogen inhibition) [13] [11].

- Function-First Screening: Prioritize strains based on genomic and metabolic data, looking for key functional genes related to your desired outcome (see Table 2) [11]. A purely taxonomy-based co-occurrence network may not ensure functional compatibility.

FAQ 3: What are the critical control points when isolating bacterial DNA from low-biomass plant samples (e.g., phyllosphere) for downstream SynCom validation?

- Problem: Low DNA yield and quality from phyllosphere samples, leading to sequencing biases and inaccurate community profiling.

- Solution & Rationale:

- Avoid Enzymatic Lysis: Protocols relying solely on enzymatic lysis often yield DNA with low purity (OD 260/280 ratios of 1.2-1.54) due to plant-derived contaminants [18].

- Recommended Protocol: A combined mechanical–chemical lysis method, followed by sonication and membrane filtration, has been shown to produce high-quality DNA (concentrations up to 38.08 ng/µL with OD 260/280 of ~1.85) suitable for advanced sequencing [18]. This method is more effective at breaking tough bacterial cell walls and minimizing co-isolation of plant compounds.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing SynCom Stability Against a Native Microbiome

This protocol uses a transwell system to evaluate SynCom persistence through chemical interactions [17].

- 1. SynCom and Native Community Preparation:

- Grow your defined SynCom to mid-log phase in an appropriate medium.

- Collect the native microbial community (e.g., soil suspension or gut microbiota sample). Centrifuge and wash cells to remove residual metabolites.

- 2. Transwell Co-culture Setup:

- Place the native community suspension in the lower well of a transwell plate.

- Place the SynCom suspension in the upper transwell insert, which has a porous membrane (e.g., 0.4 µm). This allows free passage of chemical signals and metabolites but prevents physical contact between the cell populations.

- 3. Incubation and Sampling:

- Incubate the system under conditions mimicking the target environment (e.g., temperature, pH).

- Sample the SynCom from the upper chamber at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 24, 48, 72 hours).

- 4. Analysis:

- Viability Assessment: Use flow cytometry with viability stains (e.g., propidium iodide) to quantify live, dead, and dormant cells within the SynCom [17].

- Metabolic Profiling: Assess the metabolic activity of persistent vs. non-persistent strains using phenotype microarrays (Biolog) to track utilization of carbon, nitrogen, and other substrates [17].

Protocol: A Workflow for Functional SynCom Design

This integrated workflow combines genomic and experimental data for rational SynCom assembly [11].

Functional Screening Workflow

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Functional Traits for SynCom Design

This table outlines critical functional categories and associated markers to guide the selection of microbial strains for SynComs [11].

| Functional Trait Category | Example Genes/Pathways/Compounds | Relevance in SynCom Design | Common Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Acquisition | Phosphate solubilizing genes (e.g., pqq), nitrogen fixation genes (e.g., nif), phytase | Enhances plant nutrient availability; can influence colonization ability and niche competition [11]. | Pikovskaya's agar assay for P-solubilization; nitrogen-free media; gene expression analysis. |

| Biotic Stress Resistance | Chitinases, biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for antibiotics (e.g., phenazines), siderophores | Provides direct antagonism against pathogens and induces systemic resistance in hosts [11]. | Antagonism assays on agar; CAZy database mining; LC-MS for metabolite detection. |

| Abiotic Stress Tolerance | Genes for osmolyte production (e.g., proline, glycine betaine), EPS production, heat shock proteins | Improves SynCom resilience to drought, salinity, and temperature fluctuations, aiding survival [19]. | Growth assays under stress; quantification of EPS; RT-qPCR of stress-responsive genes. |

| Host Interaction & Signaling | Genes for auxin (IAA), ACC deaminase, biofilm-forming exopolysaccharides | Modulates plant hormone levels to promote growth and enhances root colonization stability [13] [11]. | Salkowski assay for IAA; PCR for acdS gene; biofilm formation assays. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common SynCom Experimental Issues

This table summarizes specific problems, their potential causes, and evidence-based solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low DNA yield from phyllosphere samples | Inefficient bacterial cell lysis; high levels of plant contaminants. | Use a mechanical–chemical lysis protocol instead of solely enzymatic methods. | [18] |

| SynCom shows poor colonization in vivo | High competition from resident microbiota; lack of ecological niche. | Pre-screen for persistent strains; include members that form biofilms or utilize host-specific exudates. | [17] [11] |

| Inconsistent functional output | Community instability; loss of key members; unpredicted negative interactions. | Use integrated top-down/bottom-up design; perform in vitro interaction assays prior to final assembly. | [16] [13] [11] |

| Failure to reconstitute a desired phenotype | Missing key functional genes or synergistic interactions present in the native community. | Base design on functional genomic traits (Table 1) rather than taxonomy alone; consider "knock-out" communities. | [16] [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category / Item | Function & Application in SynCom Research |

|---|---|

| Model Microbial Communities | |

| Altered Schaedler Flora (ASF) | A defined 8-member community used to colonize germ-free mice, providing a standardized model for studying gut microbiome-host interactions [16]. |

| Gnotobiotic Systems | |

| Germ-Free Mice | Essential for establishing causal relationships between a SynCom and a host phenotype, as they lack any resident microbiota [16]. |

| Laboratory Tools & Assays | |

| Transwell Co-culture Systems | Permits the study of chemical interactions and competition between SynComs and native microbiomes without physical contact [17]. |

| Flow Cytometry with Viability Stains | Enables quantitative tracking of SynCom population dynamics (live, dead, dormant cells) in response to environmental challenges [17]. |

| Phenotype Microarrays (e.g., Biolog) | High-throughput screening of metabolic capabilities of individual strains or simple communities to predict functional interactions and niche preferences [17] [11]. |

| Bioinformatics & Data Resources | |

| MicrobiomeAnalyst | A web-based platform for comprehensive statistical, visual, and functional analysis of microbiome data from marker gene or shotgun sequencing [20]. |

| CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes) Database | A key resource for identifying and cataloging microbial enzymes that break down, modify, or create glycosidic bonds, crucial for assessing nutrient cycling potential [11]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models used to predict the metabolic interactions between SynCom members and to design communities with desired metabolic outputs [11]. |

| Eupalinolide H | Eupalinolide H, MF:C22H28O8, MW:420.5 g/mol |

| Eltrombopag olamine | Eltrombopag olamine, CAS:496775-62-3, MF:C29H36N6O6, MW:564.6 g/mol |

Strategies for Design and Assembly: From Trait-Based to Function-First Approaches

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Design Philosophies

Core Concept Definitions

What are the fundamental differences between bottom-up and top-down design approaches?

The design of synthetic microbial communities primarily follows two distinct philosophies, which differ in their starting point, methodology, and level of control.

Bottom-Up Design: This approach constructs synthetic microbial consortia from scratch by rationally assembling well-characterized microorganisms based on prior knowledge of their metabolic pathways and potential interactions. It offers significant control over consortium composition and function, but faces challenges in optimal assembly methods and long-term stability [21] [22].

Top-Down Design: This classical method applies selective environmental pressures to steer an existing, complex microbial community toward a desired function. While this approach leverages natural community dynamics, it can be challenging to disentangle complex microbial interactions and precisely control the resulting structure [21].

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of Design Philosophies

| Feature | Bottom-Up Approach | Top-Down Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Individual, characterized strains [21] | Complex natural community [21] |

| Methodology | Rational assembly based on known traits [21] [7] | Selective enrichment via environmental variables [21] |

| Level of Control | High control over composition [21] | Lower direct control, relies on selection [21] |

| Key Challenge | Long-term stability and predicting interactions [21] [23] | Disentangling complex interactions in a black box [21] |

| Typical Community Complexity | Defined, low-diversity consortia [24] | Complex, potentially undefined consortia [22] |

Implementation and Protocols

How do I implement a bottom-up approach to construct a synthetic consortium?

A bottom-up construction involves selecting partner strains with complementary functions and assembling them in a way that promotes the desired community-level behavior.

- Identify and Engineer Functional Strains: Select microbial strains based on known metabolic capabilities. For complex functions, you may need to genetically engineer organisms to express specific pathways, create auxotrophies (dependencies), or implement communication systems like quorum sensing [24] [23] [25].

- Assemble the Consortium: Combine the chosen strains in a co-culture. For systematic testing, a Full Factorial Assembly is ideal. This involves creating all possible combinations of your candidate strain library to empirically map the community-function landscape [26].

- Apply a Division of Labor Principle: Distribute different parts of a metabolic pathway across specialized strains. For example, one strain can be engineered to break down cellulose, while a partner strain ferments the resulting sugars into a target biofuel [24] [7].

What is the standard protocol for a top-down enrichment process?

Top-down engineering manipulates a microbial community as a whole by applying selective pressures to steer its function.

- Inoculate with a Complex Natural Sample: Start with a microbial sample from a relevant environment (e.g., soil, sediment, or marine water) that possesses the innate capability for your target function [22].

- Apply Selective Pressure: Culture the community for multiple generations under conditions that favor the desired function. This can involve providing a specific waste stream (e.g., lignocellulose) as the sole carbon source [22] or manipulating environmental parameters like pH, temperature, or salinity [21].

- Serially Passage and Stabilize: Periodically transfer the enriched culture to fresh medium under the same selective conditions. This process encourages the growth of beneficial members and leads to a stabilized, adapted community over several cycles [22].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for both design philosophies, from inception to a functional community.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My synthetically assembled bottom-up consortium is unstable. What could be the cause?

Instability in synthetic consortia often arises from uncontrolled microbial interactions.

- Problem: Cheater Strain Domination. A non-cooperating strain that benefits from public goods without contributing may outcompete essential partners [25].

- Solution: Implement Stabilizing Circuits. Engineer mutual dependency using synthetic biology. For example, create a cross-protection mutualism where each strain produces a bacteriocin that is repressed by a quorum sensing signal from the other strain. This forces coexistence, as each strain's survival depends on its partner [23].

- Problem: Unbalanced Growth or Collapse. The consortium does not maintain the intended population ratios, leading to functional failure [21].

- Solution: Refine Metabolic Interdependencies. Adjust the strength of auxotrophies or metabolic cross-feeding. Utilize computational tools like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to model and predict metabolite exchange fluxes before experimental assembly [24].

My top-down enriched community is not producing the desired function efficiently. How can I improve it?

Inefficiency in enriched consortia suggests that the selective pressure may not be optimally aligned with the target function.

- Problem: Inefficient Function. The community degrades a substrate or produces a product at a low yield [21] [22].

- Solution: Optimize Selective Conditions. Systematically vary key environmental parameters such as carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio, pH, or temperature to find the optimal conditions that strongly couple community fitness to your desired functional output [21].

- Problem: Low Abundance of Key Functional Populations. Metagenomic analysis reveals that critical degraders or producers are present but not thriving.

- Solution: Bioaugmentation. Introduce a known, high-performing strain into the enriched community to bolster the specific functional guild. This hybrid strategy combines top-down enrichment with a bottom-up modification [27] [21].

Advanced Optimization and Emerging Strategies

What are the advanced computational methods for designing and optimizing microbial communities?

Computational tools are indispensable for predicting the behavior of complex microbial systems.

- Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis: Tools like COMETS simulate microbial growth and metabolic interactions in spatially structured environments, providing predictions beyond steady-state conditions [24].

- Automated Community Design (AutoCD): This workflow uses Bayesian model selection to automatically generate and evaluate all possible genetic circuit configurations within a multi-strain system, identifying the most robust designs for achieving a stable community [23].

- Economic and Agent-Based Models: These frameworks model metabolite exchange between microbes as "trade," using principles like comparative advantage to predict stable trading partnerships and community configurations [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Community Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains [24] [25] | Engineered to lack the ability to synthesize an essential metabolite (e.g., an amino acid). | Creating obligate cross-feeding mutualisms where strains depend on each other for survival. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems [24] [23] | Genetic parts that allow cells to communicate and coordinate population-level behaviors. | Building synthetic circuits for synchronized enzyme production or population control. |

| Bacteriocins & Immunity Genes [23] | Toxins that inhibit sensitive strains and corresponding genes for self-protection. | Engineering competitive interactions or stabilization via cross-protection. |

| Microfluidic Devices (e.g., kChip) [26] | Platforms for high-throughput assembly and testing of thousands of microbial assemblages. | Screening a vast number of community combinations with minimal reagents. |

| 96-well Plates & Multichannel Pipettes [26] | Standard labware for medium-throughput culturing and assays. | Manually assembling a full factorial set of communities from a candidate strain library. |

Pathway to a Hybrid "Middle-Out" Philosophy

How can I combine the strengths of both design philosophies?

The emerging "middle-out" strategy integrates the control of bottom-up design with the evolutionary power of top-down enrichment [27] [21]. This hybrid approach involves:

- Starting with a Rationally Designed Bottom-Up Consortium composed of well-characterized strains to establish a base function.

- Applying Top-Down Selective Pressures to this defined consortium, allowing evolution to fine-tune interactions, improve efficiency, and enhance robustness in the desired environment.

- Using Omics Technologies to monitor the evolutionary changes and re-isolate improved strains, which can then be used to inform the design of next-generation, more robust synthetic communities [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind trait-based assembly of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs)? Trait-based assembly moves beyond simple taxonomic classification (e.g., species identity) to focus on the measurable, functional characteristics of individual microbes. These functional traits—such as the ability to fix nitrogen, produce specific enzymes, or tolerate oxygen—are properties that directly influence an organism's performance and its contribution to community-level functions [28]. The core principle is that by selecting and combining microbes based on their complementary functional traits, researchers can rationally design SynComs with predictable, optimized, and stable ecosystem functions, such as enhanced nutrient acquisition for plants or robust waste degradation [11].

Q2: How do I choose which functional traits to target for my specific application? Trait selection should be directly guided by the desired function of your SynCom. The table below outlines common functional trait categories and their relevance.

Table 1: Key Functional Trait Categories for SynCom Design

| Trait Category | Example Traits/Genes | Relevance in SynCom Design |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Acquisition | Chitinases, phytase, phosphate solubilizing genes (e.g., pqq), nitrogen fixation genes (e.g., nif) | Determines the consortium's ability to cycle nutrients and improve resource availability for itself or a host plant [11]. |

| Stress Tolerance | Oxygen tolerance, sporulation ability, biofilm formation | Influences ecological stability and survival in fluctuating environments, such as the shift from oxic to anoxic conditions [29]. |

| Metabolic Capabilities | Specific CAZymes, pathways for B-vitamin synthesis, utilization of root exudates | Drives division of labor, enables the consumption of complex substrates, and can prevent competitive exclusion [7] [11]. |

| Interaction-Related | Antibiotic production (e.g., phenazines), secretion systems, phytohormone production | Mediates microbe-microbe interactions (e.g., pathogen suppression) and microbe-host interactions [11]. |

Q3: What are the most common reasons for the failure of a trait-assembled SynCom? Failure often stems from overlooking ecological and practical complexities.

- Ignoring Trait Trade-offs: Microbes often face physiological trade-offs. For instance, a trait like rapid growth (associated with high 16S rRNA gene copy number) may be mutually exclusive with a trait like high resource use efficiency [29]. Selecting for one can inherently exclude the other.

- Neglecting the Environment: A trait is only advantageous in a specific context. Oxygen tolerance is critical for dispersal and initial colonization, but becomes a cost in a mature, anoxic gut environment [29]. Your experimental conditions (e.g., media, pH) must align with the selected traits.

- Overlooking Interdependence: A microbe with a desirable trait may only express it in the presence of a metabolite provided by another community member. Failure can occur if these cross-feeding or facilitative interactions are not accounted for in the design [28].

Q4: What is the difference between a comparative study and a manipulation study in trait-based research, and when should I use each? These are two distinct approaches with different strengths, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Trait-Based Research Approaches

| Aspect | Comparative Study | Manipulation Study |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Correlates naturally occurring trait patterns with environmental gradients or ecosystem functions [28]. | Directly manipulates community composition to establish a causal link between traits and function [28]. |

| Level of Trait Assessment | Community-weighted mean traits, trait distributions [28]. | Taxon-specific traits, trade-offs among traits in individual strains [28]. |

| Key Techniques | Environmental 'omics (metagenomics, metatranscriptomics), stable isotope probing [28]. | Physiological studies of individual strains, gnotobiotic systems, bottom-up community assembly [28] [7]. |

| Main Scale | The real world (field studies); complex natural communities [28]. | Laboratory (model systems); synthetic communities [28]. |

| When to Use | To generate hypotheses about which traits are important in a natural system [28]. | To test mechanistic hypotheses and establish causality under controlled conditions [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Community Instability and Functional Collapse

Symptoms: The designed SynCom fails to maintain its initial species composition over multiple generations. One or a few species dominate, leading to the loss of others and a subsequent drop in the target function.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Intense Interspecific Competition.

- Diagnosis: Check if members have overlapping niche preferences, particularly for the primary carbon or nitrogen source in your system.

- Solution: Refine your trait selection to ensure functional complementarity. Instead of selecting multiple strains that all consume glucose the fastest, choose a consortium where members specialize on different substrates (e.g., one degrades polymers, another consumes monomers) to reduce direct competition [28] [11]. This leverages the complementarity effect from BEF theory.

Cause: Lack of Facilitation or Cross-Feeding.

- Diagnosis: Analyze metabolomic data or use genome-scale metabolic modeling (GEMs) to see if a critical metabolite is missing.

- Solution: Introduce a keystone species that provides a public good. This could be a strain that breaks down a complex compound into simpler ones used by others, or one that produces an essential vitamin or siderophore that benefits the community [28]. This creates positive interdependencies that stabilize the community.

Cause: Evolutionary Pressures.

- Diagnosis: Monitor for genetic changes in constituent strains over time that might reduce their cooperative function.

- Solution: Consider imposing obligate mutualisms through genetic engineering, where two strains become interdependent for survival (e.g., by making an essential amino acid an obligate exchange metabolite) [7]. This can enhance long-term stability.

Diagram: Troubleshooting Community Instability

Problem: SynCom Fails to Achieve Target Function

Symptoms: The community is stable but does not perform the desired biochemical process (e.g., pollutant degradation, metabolite production) at the expected level.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Incorrect Trait Inference.

- Diagnosis: A trait (e.g., "chitin degradation") predicted from genome analysis may not be expressed under your experimental conditions.

- Solution: Always pair in silico trait prediction with high-throughput experimental validation [11]. Use agar plate assays (e.g., on chitin as sole carbon source) or physiological profiling (e.g., Biolog plates) to confirm phenotypic expression.

Cause: Context-Dependent Trait Expression.

- Diagnosis: The trait is present but is suppressed by the local environment (e.g., pH, oxygen tension) or by interactions with other community members.

- Solution: Optimize environmental conditions to match the trait's requirements. Furthermore, use a trait-based null model approach to determine if the observed trait distribution in your community is significantly different from a random assembly, which can help identify if environmental filtering or competitive exclusion is suppressing key traits [30].

Cause: Inadequate Functional Redundancy.

- Diagnosis: Only one member of the SynCom possesses the critical trait, and it is sensitive to small environmental fluctuations.

- Solution: Incorporate multiple, phylogenetically distinct strains that possess the same key trait. This provides insurance against the failure of any single strain and increases the robustness of the function, a key insight from biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Function-Informed SynCom Design

This protocol outlines a multidimensional strategy that integrates computational genomics with high-throughput phenotyping to select optimal strains for a SynCom [11].

Diagram: SynCom Design Workflow

Procedure:

- Sample and Isolate: Collect environmental samples relevant to your target function (e.g., rhizosphere soil for plant growth promotion). Isolate a large number of pure bacterial cultures.

- Genome Sequencing and In Silico Trait Mining: Sequence the genomes of all isolates. Use bioinformatics tools to mine for genes related to your target function (see Table 1). Examples include:

- High-Throughput Phenotyping: Validate genomic predictions experimentally.

- Substrate Utilization: Use phenotype microarrays (e.g., Biolog GEN III plates or custom Eco-Plates) to profile carbon source usage [28] [11].

- Functional Assays: Perform plate-based assays for specific traits (e.g., siderophore production on CAS agar, phosphate solubilization on Pikovskaya's agar, antagonism against a pathogen) [11].

- Interaction Screening: Pairwise co-culture strains to identify positive (facilitation) and negative (inhibition) interactions. This helps avoid incompatible combinations and identify potential synergistic partners [11].

- In Silico Modeling with GEMs: For a shortlist of strains, reconstruct Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs). Use these models to predict potential metabolic interactions, such as cross-feeding, and to simulate community growth and function in silico before moving to wet-lab assembly [11].

- Final Strain Selection: Integrate all data—genomic potential, confirmed phenotypes, interaction patterns, and modeling results—to make a final, rational selection of strains for your SynCom.

Protocol 2: Inferring Traits for Unculturable Taxa via Phylogeny

This protocol allows for the prediction of traits for microbial taxa that cannot be easily cultured, which is essential for designing SynComs based on meta'omic data [29].

Procedure:

- Build a Comprehensive Phylogeny: Generate a high-resolution phylogenetic tree that includes your OTUs/ASVs from sequencing data along with a large number of reference taxa with formally described traits (e.g., from type culture collections) [29].

- Map Known Trait Data: Curate trait data for the reference taxa from literature and culture collection databases. Map these known trait values onto the corresponding tips of the phylogeny [29].

- Infer Unknown Traits: Use phylogenetic comparative methods (e.g., hidden state prediction, ancestral state reconstruction) to infer the trait values for the OTUs/ASVs with unknown traits, based on the evolutionary relationships and the traits of their close relatives [29].

- Calculate Community-Weighted Means (CWMs): For each sample, calculate the CWM of a trait. This is the mean trait value of all OTUs/ASVs in that community, weighted by their relative abundance. Formula:

CWM = Σ (p_i * t_i), wherep_iis the relative abundance of OTU i and `t_i* is its trait value [29]. Shifts in CWMs over time or across conditions can reveal the mechanisms of community assembly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Trait-Based SynCom Research

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Systems | Sterile growth chambers (for plants or animals) that allow inoculation with a known set of microbes. | Essential for testing the causal effects of your SynCom on a host function without interference from a background microbiota [11]. |

| Phenotype Microarrays (e.g., Biolog) | Multi-well plates pre-coated with different carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus sources. | High-throughput profiling of microbial substrate utilization profiles, a key set of functional traits [28] [11]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models that simulate the entire metabolic network of an organism. | Used to predict metabolic capabilities, resource competition, and potential cross-feeding interactions between SynCom members in silico [11]. |

| Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) | Technique using stable-isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., ¹³C) to track their incorporation into DNA/RNA. | Identifies which members of a complex community are actively utilizing a specific substrate, linking identity to function [28]. |

| AntiSMASH Database | A bioinformatics platform for the genome-wide identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). | Used to mine microbial genomes for their potential to produce antibiotics, siderophores, or other bioactive compounds [11]. |

| CAZy Database | A knowledge resource on Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes. | Essential for identifying microbes with the genomic potential to degrade complex plant polysaccharides or other carbohydrates [11]. |

| GSK317354A | GSK317354A, MF:C25H18F4N6O, MW:494.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arv-771 | Arv-771, MF:C49H60ClN9O7S2, MW:986.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Function-First SynCom Design

This guide addresses specific technical challenges researchers may encounter when applying function-first selection methods for Synthetic Community (SynCom) construction.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Representation | SynCom does not capture key ecosystem functions [3] | • Over-reliance on taxonomy• Missing core/critical functions• Inadequate genome collection | • Prioritize functional over taxonomic profiling [3]• Assign additional weights to core functions (>50% prevalence) and differentially enriched functions (P-value < 0.05) [3] |

| Community Stability | Member strains fail to coexist; community collapses [3] [31] | • Metabolic incompatibility• Unchecked competition• Lack of synergistic interactions | • Use genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., GapSeq) with tools like BacArena for in silico coexistence testing [3]• Design communities with ~13 members on average to balance diversity and stability [3] |

| Metagenomic Data Processing | High complexity and fragmented sequences hinder binning [32] | • High genomic diversity in sample• Uneven sequencing coverage• Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | • Use hybrid binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT 2) that combine sequence composition and coverage information [32]• Apply tools like CheckM to evaluate MAG quality and completeness [32] |

| Strain-Level Resolution | Inability to track specific strains in a community [33] | • Low sequencing coverage• Co-existing strain mixtures• Limited reference databases | • Employ statistical strain deconvolution tools (e.g., StrainFacts) to infer genotypes and abundances from metagenotypes [33] |

| Experimental Validation | SynCom fails to induce expected phenotype in vivo [3] | • Poor functional representation of disease state• Neglect of host-microbe interactions | • When modeling disease, weight functions differentially enriched in diseased vs. healthy metagenomes [3]• Use gnotobiotic mouse models (e.g., IL10−/− for colitis) for validation [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle behind a "function-first" selection approach for SynComs?

A function-first approach selects strains for a Synthetic Community based on the key functions they encode, rather than their taxonomic identity [3]. These target functions are first identified from metagenomic data of the ecosystem one wishes to mimic. The goal is to create a simplified community that captures the functional landscape of the original, complex microbiome, ensuring it fills the same ecological niches [3].

2. Why should I use a function-first approach instead of selecting phylogenetically representative species?

While taxonomic selection is common, it may exclude taxa that provide critical functionality [3]. A function-first strategy directly addresses this by prioritizing the preservation of ecosystem-level processes. This is particularly important for modeling diseases, as you can deliberately over-represent functions associated with a diseased state to create a model system that recapitulates key phenotypes, such as inducing colitis in mouse models [3].

3. What are the key computational steps in a standard function-first workflow?

A standard pipeline, such as MiMiC2, involves several key steps [3]:

- Annotation: Predicting and annotating protein sequences from both metagenomic assemblies and isolate genomes (e.g., using Prodigal and hmmscan against Pfam).

- Vectorization: Creating binarized presence/absence vectors of protein families (Pfam) for both the metagenomes and the available genomes.

- Weighting and Selection: Assigning weights to core and differentially enriched functions, then iteratively selecting the highest-scoring genomes from a collection to build the SynCom.

4. How can I predict if my selected strains will coexist stably before moving to lab cultures?

Genome-scale metabolic modeling is a powerful method for this. Tools like GapSeq can generate metabolic models for each candidate strain, and platforms like BacArena can simulate the growth and metabolic interactions of these models in a shared virtual environment [3]. This provides in silico evidence for cooperative potential and coexistence, allowing for community optimization prior to costly and time-consuming experimental validation [3].

5. What is functional redundancy and why is it a challenge in SynCom design?

Functional redundancy occurs when multiple species in a community are capable of performing the same function [34]. This can be a challenge for interpretation because it complicates the link between a specific function and a single taxonomic entity. Furthermore, reduced variability in a functional profile across communities is often interpreted as evidence of selection for that function, but it can also arise simply from statistical averaging when summing the abundances of multiple taxa that share the function, even in the absence of direct selection [34]. Careful null model analysis is needed to distinguish between these scenarios.

Experimental Protocol: Core Function-Weighted SynCom Assembly

This protocol outlines the key methodology for constructing a function-directed SynCom, based on the MiMiC2 pipeline [3].

1. Metagenomic and Genomic Data Preparation

- Input: Obtain metagenomic sequencing reads from the target ecosystem (e.g., healthy vs. diseased human gut).

- Quality Control & Assembly: Filter out host reads using a tool like BBMAP. Assemble the high-quality microbial reads into contigs using an assembler such as MEGAHIT [3].

- Functional Annotation: Predict the proteome from the assembled contigs using Prodigal in meta-mode (

-p meta). Annotate the resulting protein sequences against a functional database (e.g., Pfam) using hmmscan [3]. - Genome Collection: Curate a collection of isolate genomes or high-quality Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from a relevant source (e.g., human gut isolates). Annotate their proteomes in the same manner as the metagenomes.

2. Function Vectorization and Weighting

- Vectorization: Convert the Pfam annotations for both the metagenomic samples and the genome collection into binarized vectors, indicating the presence or absence of each protein family [3].

- Identify Core Functions: Calculate the prevalence of each Pfam across the metagenomic samples. Pfams present in >50% of samples are designated "core" and given an additional weight (default: 0.0005) [3].

- Identify Differentially Enriched Functions: If comparing two sample groups (e.g., Healthy vs. Disease), use a Fischer's exact test to find Pfams with significantly different prevalence (P-value < .05). These are given an additional weight (default: 0.0012) [3].

3. Iterative Strain Selection

- Scoring and Selection: For each metagenome, compare the Pfam vector of every genome in the collection to the metagenome's Pfam vector.

- The score for a genome is the sum of weights for all matching Pfams (Pfam present in both the genome and metagenome). Pfams in the genome but not the metagenome (mismatches) do not contribute to the score.

- The highest-scoring genome is selected for the SynCom.

- Iteration: The Pfams encoded by the selected genome are accounted for, and the scoring process is repeated iteratively until the desired number of strains is selected or the functional representation is deemed sufficient [3].

4. In Silico Community Validation with Metabolic Modeling

- Model Generation: Create a genome-scale metabolic model for each selected strain using a tool like GapSeq [3].

- Simulation: Use a metabolic modeling toolkit like BacArena to simulate community behavior.

- Create an "arena" representing the environment.

- Load the metabolic models and set a default medium.

- Place virtual cells of the SynCom members into the arena.

- Simulate growth over a set period (e.g., 7 hours).

- Analysis: Extract growth data to evaluate potential for cooperative coexistence before proceeding to in vitro assembly [3].

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the key stages of the function-first SynCom construction pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Software

| Category | Item | Function in SynCom Design |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | MEGAHIT [3] | De novo assembler for metagenomic short reads. |

| Prodigal [3] | Predicts protein-coding genes in microbial genomes and metagenomes. | |

| HMMER (hmmscan) [3] | Scans protein sequences against profile-HMM databases (e.g., Pfam) for functional annotation. | |

| MetaBAT 2 [32] | Bins assembled contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using tetranucleotide frequency and coverage. | |

| CheckM [32] | Assesses the quality and completeness of MAGs. | |

| StrainFacts [33] | Deconvolutes strain-level genotypes and abundances from metagenomic data. | |

| Metabolic Modeling | GapSeq [3] | Generates genome-scale metabolic models from genomic data. |

| BacArena [3] | Simulates the growth and interactions of metabolic models in a shared environment. | |

| SynCom Design | MiMiC2 [3] | A computational pipeline for the function-based selection of SynCom members from metagenomic data. |

| Reference Databases | Pfam [3] | A large collection of protein families, each represented by multiple sequence alignments and hidden Markov models (HMMs). |

| APY0201 | APY0201, MF:C23H23N7O, MW:413.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CRT0066101 | CRT0066101, MF:C18H22N6O, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Leveraging Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMM) for In Silico Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Model Reconstruction and Curation

FAQ 1: My draft model cannot produce biomass on a minimal medium. What is wrong and how can I fix it?

- Problem: Draft metabolic models, built from genome annotations, often contain gaps—missing reactions or transporters—that prevent them from producing all essential biomass precursors [35] [36].

- Diagnosis: Use the

GapFindalgorithm or similar functionality in your modeling platform (e.g., KBase, COBRA Toolbox) to identify dead-end metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed [37]. - Solution: Perform gap-filling. This computational process adds a minimal set of reactions from a biochemical database to enable biomass production [36].

- Protocol:

- Specify Media: Clearly define the growth medium for the gap-filling process. Using a minimal medium is often best for the initial gap-filling, as it forces the model to biosynthesize many essential substrates [36].

- Run Gap-filling Algorithm: Use tools like the KBase "Gapfill Metabolic Model" app or the

fillGapsfunction in COBRA Toolbox. These typically use Linear Programming (LP) to minimize the sum of flux through gapfilled reactions, effectively finding the most parsimonious solution [36]. - Inspect Added Reactions: After gap-filling, review the added reactions. Sort the model's reaction list by the "Gapfilling" column to see which were added. Manually curate this list, as the algorithm may add reactions based on network connectivity rather than biological evidence [36].

- Troubleshooting: If the gap-filled solution seems biologically irrelevant, you can:

- Protocol:

FAQ 2: How do I choose a template model for reconstructing a GEM for a non-model organism?

- Problem: Automatic reconstruction from genome annotation alone can be error-prone, especially for non-model organisms with limited biochemical data [38] [39].

- Solution: Use a semi-automated, homology-based pipeline that leverages existing, high-quality models as templates.

- Protocol (using the RAVEN Toolbox):

- Identify Template Models: Survey the literature for high-quality GEMs. The choice is a trade-off between phylogenetic proximity and tissue/organism specificity. For a fish liver model, you might choose a human liver model over a generic zebrafish model for its more relevant metabolic scope [38].

- Perform Homology Search: Use the

getBlastfunction in RAVEN to create a structure with homology measurements between your target organism and the template organism(s) [38]. - Generate Draft Reconstruction: Use the

getModelFromHomologyfunction to create a draft model containing reactions associated with orthologous genes [38].

- Troubleshooting: Be aware that the quality of the draft model is highly impacted by the quality of the template model and the genome annotation of your target organism. Manual curation is always necessary [38].

- Protocol (using the RAVEN Toolbox):

FAQ 3: How can I account for uncertainty in my model's gene annotations?

- Problem: Homology-based gene annotations are imperfect, leading to incorrect or missing Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations, which is a major source of uncertainty in GEMs [39].

- Solution: Utilize probabilistic annotation and ensemble modeling approaches.

- Protocol:

- Probabilistic Annotation: Use pipelines like ProbAnno (within the ModelSEED framework) or GLOBUS instead of binary yes/no annotations. These tools assign a probability to each metabolic reaction being present based on homology scores, phylogenetic profiles, and other genomic context information [39].

- Generate Model Ensembles: Create not one, but multiple versions of your GEM that represent plausible alternative network structures based on the probabilistic annotations [39].

- Test Predictions: Run simulations across the entire ensemble of models. Predictions that are consistent across most models are considered robust, while variable predictions highlight areas sensitive to annotation uncertainty [39].

- Protocol:

Simulation and Analysis

FAQ 4: My model's Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions do not match experimental growth or secretion rates. What could be the cause?

- Problem: FBA predictions are highly sensitive to the constraints applied to the model, particularly exchange reaction bounds and the biomass objective function [35] [39].

- Diagnosis & Solution: