Strategies for Mitigating Noise and Crosstalk in Synthetic Genetic Circuits: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Synthetic genetic circuits are revolutionizing biotechnology and therapeutic development, but their reliability is often compromised by noise and crosstalk, which can lead to unpredictable behavior and functional failure.

Strategies for Mitigating Noise and Crosstalk in Synthetic Genetic Circuits: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Synthetic genetic circuits are revolutionizing biotechnology and therapeutic development, but their reliability is often compromised by noise and crosstalk, which can lead to unpredictable behavior and functional failure. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of these challenges, exploring the fundamental mechanisms of circuit-host interactions, resource competition, and non-orthogonal signaling. We examine cutting-edge mitigation strategies, including orthogonal operational amplifiers, resource-aware design, and novel physical buffering through phase separation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes troubleshooting methodologies and validation frameworks essential for constructing robust, predictable genetic systems. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical applications and future perspectives, this work serves as a guide for advancing synthetic biology toward more reliable clinical and industrial deployment.

Understanding the Sources: Noise, Crosstalk, and Circuit-Host Interactions in Synthetic Biology

FAQs: Understanding Core Concepts

What is the fundamental difference between "noise" and "crosstalk" in genetic circuits?

Noise (or stochasticity) refers to random fluctuations in gene expression that cause genetically identical cells in the same environment to exhibit variation in protein levels and other molecular components. This arises from the inherently stochastic nature of biochemical reactions, such as transcription and translation, where low-copy-number molecules lead to cell-to-cell variability [1].

Crosstalk occurs when components of a synthetic circuit inappropriately interact with each other or with the host's native systems. For example, a sensor designed for one specific signal (e.g., Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) might inadvertently respond to a non-cognate signal (e.g., paraquat), compromising the circuit's specificity and function [2].

How does growth-mediated feedback interfere with circuit memory?

A feedback loop exists between synthetic circuits and host cells: circuit expression consumes cellular resources, burdening the host and slowing cell growth. In turn, fast cell growth dilutes circuit components. This growth-mediated dilution can rapidly erase the memory of bistable switches. Research shows that a self-activation (SA) switch quickly loses its memory during exponential growth phases because the circuit products are diluted faster than they can be replenished [3].

Can noise ever be beneficial for synthetic genetic circuits?

Yes, while often considered a nuisance, noise can be functionally beneficial. Cells may exploit internal noise to cope with unpredictable environments, and it can be a source of variability for adaptation. In synthetic systems, noise has been used to generate complex patterns, such as in engineered bacteria that exhibit stochastic Turing patterns for tissue formation [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Loss of Circuit Memory

Symptoms: A bistable switch (e.g., a self-activation circuit) fails to maintain its state after cell dilution into fresh medium. The population reverts to the OFF state instead of showing hysteresis.

Underlying Mechanism: This is typically caused by growth-mediated dilution [3]. When "ON" cells are diluted into fresh medium, they enter a rapid growth phase. The increased dilution rate of the circuit's proteins (e.g., transcription factors) outpaces their production, collapsing the circuit's state before growth slows again.

Solutions:

- Circuit Topology Selection: Choose a toggle switch topology over a self-activation switch. The toggle switch has been demonstrated to be more refractory to growth-mediated dilution and can recover its memory after the fast-growth phase [3].

- Decouple from Growth Feedback: Engineer the circuit to minimize the metabolic burden on the host, thereby reducing the growth feedback that leads to dilution.

- Mathematical Modeling: Develop a model that integrates both circuit dynamics and cell growth to predict and identify dilution-prone designs before experimental implementation [3].

Problem: Crosstalk in Multi-Sensor Systems

Symptoms: A sensor circuit designed to detect a specific input (e.g., Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ via the OxyR system) shows an undesired response to a different, non-cognate signal (e.g., paraquat).

Underlying Mechanism: Pathway crosstalk occurs due to a lack of specificity at the molecular level. A transcription factor or promoter might respond to multiple stimuli, or shared cellular resources might create indirect interference [2].

Solutions:

- Crosstalk Compensation: Instead of solely trying to insulate the pathways, build a compensatory circuit. Use a second sensor that specifically detects the interfering signal and integrates its output to subtract the unintended effect from the primary sensor's signal [2].

- Promoter and Factor Engineering: Characterize and select highly specific promoters. For instance, among OxyR-activated promoters,

oxySpdemonstrated superior performance with high output fold-induction and a wide input range [2]. - Utility Metric Analysis: Quantify sensor performance using a utility metric (Utility = Relative Input Range × Output Fold-Induction). This helps select components that minimize ambiguous outputs [2].

Problem: Low or Silenced Transgene Expression

Symptoms: A circuit that initially functions correctly gradually loses expression over time, especially in primary or stem cells.

Underlying Mechanism: Transgene silencing, often through epigenetic modifications that make the synthetic construct inaccessible to the transcriptional machinery [4].

Solutions:

- Insulator Elements: Flank the synthetic circuit with chromatin insulators to protect it from silencing effects from the genomic integration site.

- Epigenetic Engineering: Modify the synthetic DNA sequence to avoid known silencing motifs or incorporate elements that promote an open chromatin state.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Quantifying Sensor Crosstalk

Objective: To measure the degree of crosstalk between two sensor circuits (e.g., an Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor and a paraquat sensor) in a single cell.

- Strain Construction: Create a dual-sensor strain. For example, integrate a paraquat-sensing circuit (using SoxR and the

pLsoxSpromoter driving mCherry) with an Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-sensing circuit (using OxyR and theoxySppromoter driving sfGFP) on separate plasmids with different copy numbers [2]. - Stimulation: Expose the strain to a range of concentrations for:

- The cognate inducer (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚)

- The non-cognate inducer (paraquat)

- Both inducers simultaneously

- Measurement: Use flow cytometry to measure the fluorescence output (mCherry and sfGFP) for each condition at the single-cell level.

- Data Analysis:

- Generate input-output transfer curves for each sensor under the different induction schemes.

- Fit the data to Hill functions.

- Calculate the utility metric for each sensor when alone and in the presence of the other inducer to quantify performance degradation [2].

Protocol: Characterizing Growth-Mediated Memory Loss

Objective: To test the robustness of a bistable switch's memory under dynamic growth conditions.

- Circuit Activation: Start with populations of cells in the "OFF" state and "ON" state (pre-treated with a high dose of inducer).

- Dilution and Monitoring: Dilute both populations into fresh medium with varying concentrations of the inducer.

- Time-Course Tracking: Measure both the optical density (OD at 600 nm) to monitor growth and the fluorescence/OD to monitor circuit state over time (e.g., every hour for 6-8 hours) [3].

- Analysis:

- Plot growth curves and fluorescence dynamics.

- A rapid decline in fluorescence per OD during the exponential growth phase indicates memory loss due to dilution.

- Compare the steady-state fluorescence after growth stabilizes to the initial state to confirm if memory was retained.

| Circuit Design | Constitutive oxyR Expression Plasmid | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Utility Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (oxySp) | Medium-Copy | 15.0 | 58.4 | 876.0 |

| Open-Loop (ahpCp) | Medium-Copy | Not Specified | Not Specified | 214.9 |

| Open-Loop (katGp) | Medium-Copy | Not Specified | Not Specified | 324.2 |

| Open-Loop, Tuned | High-Copy | 23.6 | 63.0 | 1486.8 |

| Positive Feedback | High-Copy (as fusion) | 15.9 | 72.5 | 1152.8 |

| Circuit Design | IPTG Concentration | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Utility Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop | Not applicable | 42.3 | 95.8 | 4052.3 |

| Positive Feedback | Not applicable | 10.2 | 82.6 | 842.5 |

| Genomic SoxR only | Not applicable | Not Specified | Not Specified | 4364.7 |

| Tuned Open-Loop | Lowest tested | Highest achieved | Highest achieved | 11,620.0 |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| OxyR Transcription Factor | Activates promoters in response to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚; core component of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor circuits. | Allows construction of analog sensor circuits with graded responses [2]. |

| SoxR Transcription Factor | Activates promoters in response to superoxide and paraquat; core of paraquat sensors. | Can be used to build orthogonal sensing systems [2]. |

| oxySp Promoter | OxyR-regulated promoter used for constructing Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-responsive gene circuits. | High utility metric, combining good fold-induction and a wide input range [2]. |

| pLsoxS Promoter | SoxR-regulated promoter used for constructing paraquat-responsive gene circuits. | A synthetic promoter made by fusing a SoxR binding site to a phage promoter region [2]. |

| Dual-Sensor Strain | A single strain harboring multiple sensor circuits to study pathway crosstalk. | Enables quantification of unintended interactions between different signal transduction pathways [2]. |

| Mathematical Model (Growth-Integrated) | A computational model that includes both gene circuit dynamics and host cell growth. | Predicts topology-dependent effects of growth-mediated dilution on circuit function (e.g., memory loss) [3]. |

| Scandine N-oxide | Scandine N-oxide, MF:C21H22N2O4, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Boeravinone A | Boeravinone A, MF:C18H14O6, MW:326.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

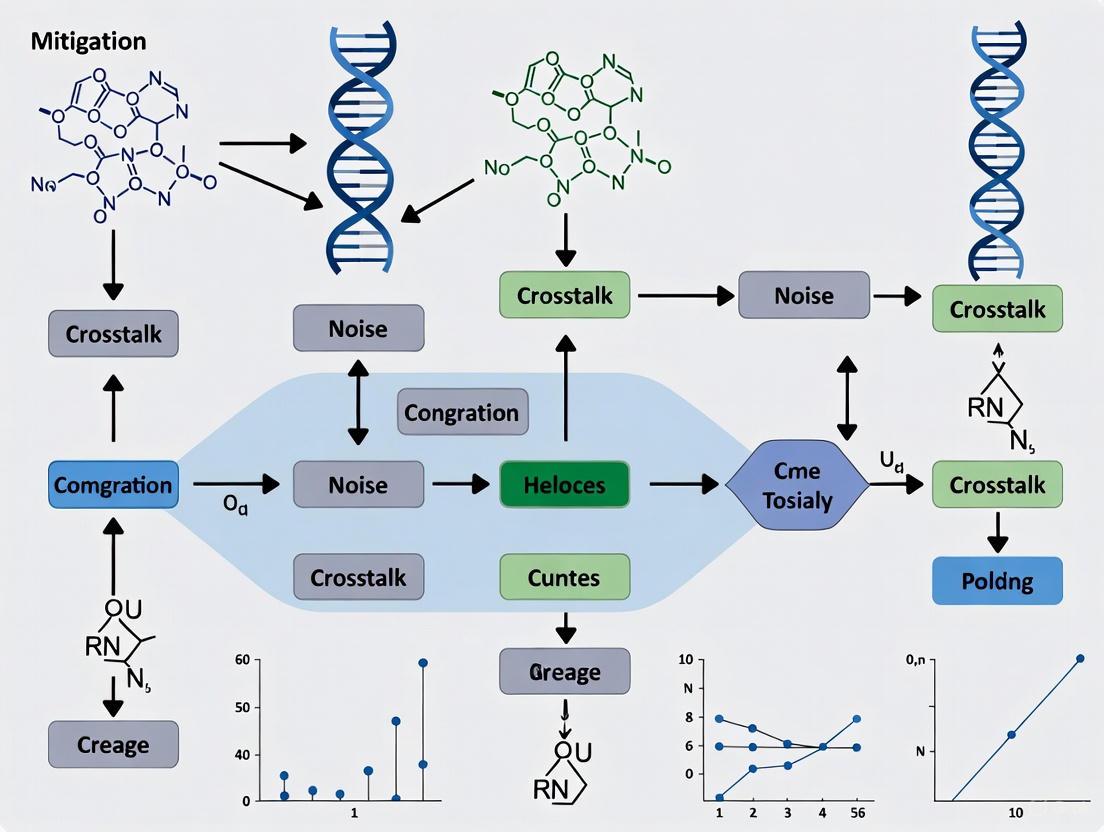

Signaling Pathway & Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Growth Feedback Loop

Diagram 2: Crosstalk Compensation Design

The Impact of Metabolic Burden and Resource Competition on Circuit Performance

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary symptoms of metabolic burden in my bacterial culture? A: The most common symptoms are a reduced cellular growth rate and a decrease in the overall biomass accumulated over time. This occurs because the host cell redirects essential resources, like ribosomes and energy, away from growth and maintenance to express your synthetic circuit [5].

Q2: How does resource competition differ from direct genetic crosstalk? A: Resource competition is an indirect coupling where multiple genes (both native and synthetic) compete for a limited, shared pool of cellular machinery, such as ribosomes, RNA polymerases, and nucleotides [5]. Direct crosstalk, in contrast, involves unintended biochemical interactions between circuit components, such as a transcription factor binding to a non-cognate promoter [6]. Both can lead to performance glitches, but they require different mitigation strategies.

Q3: What circuit design strategies can make my system more robust to burden? A: Key strategies include:

- Implementing Orthogonality: Using components (e.g., transcription and translation machinery) from other organisms that do not interact with the host's native systems [6] [7].

- Employing Feedback Control: Designing circuits with negative feedback loops to maintain stable protein levels and make output robust to resource fluctuations [5].

- Distributing Functions: In a consortium-based approach, distributing different circuit modules across multiple cell populations can isolate and reduce the burden on any single cell [8].

Q4: My circuit works in a test tube but fails in the host organism. Could resource competition be the cause? A: Yes, this is a classic symptom. In vitro testing does not replicate the dynamic, resource-limited environment of a living cell. Once inside the host, your circuit must compete for finite resources, which can alter its dynamic behavior, lead to unexpected coupling between seemingly independent modules, and even trigger stress responses that degrade performance [9] [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Failures

Problem: Unstable or Oscillatory Circuit Output

- Potential Cause: High metabolic burden triggering a stress response (e.g., ppGpp alarmone production) that globally modulates resource availability, creating a feedback loop between circuit performance and host health [5].

- Solutions:

- Weaken the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strength of your circuit genes to lower their translation demand and resource consumption [6] [5].

- Re-engineer the circuit to include an orthogonal ribosome system, creating a dedicated pool of ribosomes for your circuit that does not compete with host genes [5].

Problem: Circuit Performance Drifts Over Time or Between Cell Generations

- Potential Cause: Mutations that alleviate the metabolic burden imposed by the circuit. Cells with mutations that inactivate or downregulate your circuit have a growth advantage and will outcompete the desired cells over time [5].

- Solutions:

- Couple your circuit to an essential host gene, so that cells cannot lose the circuit without a fitness cost.

- Use a more stable genetic architecture (e.g., genomic integration instead of high-copy plasmids) to reduce the rate of loss.

- Implement a biomolecular controller that actively stabilizes the concentration of a key shared resource, like ribosomes [5].

Problem: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio and High Cell-to-Cell Variability

- Potential Cause: Extrinsic noise stemming from cell-to-cell differences in the concentrations of limiting resources (e.g., free RNA polymerase). This is exacerbated by resource competition [9].

- Solutions:

Data and Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Effects of Metabolic Burden

The tables below summarize key relationships and experimental parameters for understanding and quantifying metabolic burden.

Table 1: Quantifying the Impact of Synthetic Gene Expression on Host Cells

| Metric | Observed Effect | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Linear decrease with increasing heterologous protein load [5]. | Measure optical density (OD600) over time in a microplate reader. Calculate the maximum growth rate (μ) during exponential phase. |

| Ribosome Mass Fraction | Deviation from the classic bacterial growth law; fraction may not scale linearly with growth rate under high burden [5]. | Quantify ribosomal RNA via quantitative PCR (qPCR) or use a fluorescent reporter under a ribosomal promoter. |

| ppGpp Level | Increase in concentration, indicating a stringent response triggered by resource scarcity [5]. | Use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) or fluorescent biosensors to measure intracellular ppGpp. |

| Circuit Output | Sub-linear or non-monotonic response to input signals due to saturation of shared resources [5]. | Measure output promoter activity using flow cytometry (e.g., via GFP reporter). |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Resource-Aware Circuit Modeling

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range (E. coli) |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Pool Size (Ribosomes) | Total available ribosomes for translation. | Varies with growth rate; ~20,000-70,000 per cell [5]. |

| Transcription Rate (ktxn) | Rate of mRNA production from a promoter. | 0.1 - 10 mRNA/min/gene [5]. |

| Translation Rate (ktl) | Rate of protein production per mRNA. | 1 - 100 protein/min/mRNA (depends on RBS strength) [6] [5]. |

| mRNA Degradation Rate (γm) | Inverse of mRNA half-life. | 0.1 - 1 minâ»Â¹ (half-life of ~1-10 min) [6]. |

| Protein Degradation Rate (γp) | Inverse of protein half-life (includes dilution from growth). | 0.01 - 0.05 minâ»Â¹ (for stable proteins) [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Resource Competition

This protocol outlines steps to determine if your circuit's failure is linked to resource competition.

Goal: To correlate circuit-induced growth rate reduction with changes in ribosomal mass fraction and circuit output.

Materials:

- Strains: (1) Wild-type host strain, (2) Host strain carrying your synthetic gene circuit, (3) Control strain carrying a low-burden scaffold (e.g., empty vector).

- Equipment: Microplate reader, flow cytometer, qPCR machine.

- Reagents: Growth medium, SYBR Green qPCR kit, primers for 16S rRNA and a housekeeping gene.

Methodology:

- Growth Curve Analysis:

- Inoculate all three strains in triplicate in a 96-well deep-well plate with your chosen medium.

- Transfer to a clear-bottom 96-well plate and monitor OD600 in a microplate reader for 12-24 hours.

- Analysis: Calculate the maximum growth rate (μ) for each culture from the exponential phase of the growth curve.

Sampling for Ribosomal Content and Circuit Output:

- For each strain, sample cells during mid-exponential phase (e.g., OD600 ≈ 0.5).

- Split the sample: one part for RNA extraction (for qPCR) and one part for fixation and flow cytometry.

Ribosomal Mass Fraction via qPCR:

- Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR using primers for 16S rRNA (a proxy for ribosome number) and a housekeeping gene (e.g., rpoD) for normalization.

- Analysis: Use the ΔΔCt method to calculate the relative abundance of 16S rRNA in your circuit strain compared to the wild-type and empty vector controls.

Circuit Output via Flow Cytometry:

- Analyze the fixed cells from Step 2 using a flow cytometer to measure the fluorescence from your circuit's output reporter (e.g., GFP).

- Analysis: Compare the mean fluorescence intensity and the distribution (noise) across the three strains.

Interpretation: A significant reduction in both growth rate and ribosomal mass fraction in your circuit strain, compared to the controls, is a strong indicator of high metabolic burden. If the circuit output is also lower than expected or highly variable, it is likely suffering from resource competition.

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

The ppGpp-Mediated Resource Allocation Pathway

This diagram illustrates the key pathway through which high circuit burden triggers the stringent response, leading to growth rate reduction.

Resource-Aware Circuit Design Workflow

This workflow provides a methodology for designing genetic circuits that account for resource competition from the outset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Mitigating Metabolic Burden and Crosstalk

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ/anti-σ Factor Pairs [6] | Engineered transcription factors that do not interact with the host's native regulatory network. Used to build synthetic operational amplifiers (OAs) that decompose complex signals. | Enables precise, modular circuit design with minimal direct genetic crosstalk. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase & Lysozyme [6] | An orthogonal polymerase system from bacteriophage T7. The lysozyme acts as a specific inhibitor, allowing for tunable negative feedback in OA circuits. | Provides a dedicated, high-level transcription resource that can be dynamically controlled. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Libraries [6] [5] | A collection of DNA sequences with varying translation initiation strengths. Used to fine-tune the translation rate and resource demand of each circuit gene. | Allows for balancing gene expression to minimize burden and optimize system performance. |

| Coarse-Grained Bacterial Cell Model [5] | A mathematical model that simulates host cell resource allocation (ribosomes, nucleotides) and growth in response to synthetic circuit expression. | Predicts burden effects and circuit performance in silico before costly experimental implementation. |

| Multicellular Control Architecture [8] | A design paradigm where complex circuit functions are distributed across different cell populations in a consortium. | Reduces burden on individual cells by isolating resource-intensive modules, enhancing overall system stability. |

| Tenulin | Tenulin, CAS:55780-22-8, MF:C17H22O5, MW:306.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Picrasin B acetate | Picrasin B acetate, MF:C23H30O7, MW:418.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common Growth Feedback Issues

FAQ 1: My synthetic gene circuit loses its memory or bistable state over time. Could growth feedback be the cause?

Yes, this is a documented effect of growth feedback. The functional failure of memory circuits, such as a loss of bistability, is a common symptom. The underlying mechanism often involves the growth-mediated dilution of circuit components like transcription factors and proteins. During rapid cell growth, the increased dilution rate can shift the balance between protein production and degradation, effectively erasing a programmed state [10] [11]. This effect is highly topology-dependent; for instance, a self-activation switch is more prone to memory loss than a toggle switch built with mutual repression [10].

FAQ 2: Why does my circuit's output show high, unpredictable fluctuations in a multi-module system?

These fluctuations are frequently due to resource competition, a phenomenon closely linked to growth feedback. When multiple synthetic modules compete for limited, shared cellular resources—such as RNA polymerases, ribosomes, and nucleotides—it introduces an additional layer of noise and can cause anti-correlated fluctuations in the expression levels of different genes [12]. This competition acts as a hidden coupling between otherwise independent circuit modules.

FAQ 3: My sensor circuit is producing non-specific readings. Is this related to growth conditions?

Crosstalk between signaling pathways can be exacerbated by the cellular state during growth. A novel strategy to combat this is not insulation, but crosstalk compensation. This involves designing a network that integrates signals from a primary sensor and a sensor for the interfering input, using the latter's signal to computationally cancel out the crosstalk at the network level [2].

Key Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Growth Feedback

Protocol: Quantifying Growth-Mediated Dilution in a Bistable Switch

This protocol outlines a method to test the robustness of a bistable memory circuit against growth feedback, based on research that compared self-activation and toggle switches [10].

- Objective: To determine how different growth rates affect the stability of a programmed bistable state.

- Key Materials:

- Strains: E. coli strains harboring the self-activation switch or the toggle switch circuits.

- Inducers: Specific molecules to set the circuit to its "ON" or "OFF" state (e.g., L-ara for pBad-AraC systems).

- Growth Media: Use different media (e.g., rich vs. minimal) to create cultures with varying maximum growth rates.

- Methodology:

- Pre-conditioning: Inoculate separate cultures and use the appropriate inducer to program one set to the "ON" state and another to the "OFF" state.

- Growth Phase: Dilute the pre-conditioned cultures into fresh media that supports fast growth. Do not re-apply the inducer.

- Measurement and Analysis: After several hours of growth, measure the output (e.g., fluorescence) of the cultures.

- Expected Outcome: A circuit sensitive to growth dilution (e.g., the self-activation switch) will show a loss of memory, with both pre-conditioned cultures converging to the same output. A robust circuit (e.g., the toggle switch) will maintain distinct "ON" and "OFF" populations [10].

Protocol: Mapping a Circuit's Input-Output Transfer Curve

This method is used to quantitatively characterize a sensor circuit's performance and its utility under different conditions [2].

- Objective: To measure the input dynamic range and output fold-induction of a sensor circuit, which are used to calculate its "utility" as an analog sensor.

- Key Materials:

- Sensor Circuit: A plasmid-based circuit with a sensor (e.g., OxyR for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, SoxR for paraquat) controlling a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, mCherry).

- Input Signal Gradient: A range of concentrations for the input molecule (e.g., 0-1.2 mM Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚).

- Methodology:

- Induction: Expose separate cultures of the sensor strain to different concentrations of the input signal.

- Measurement: Use flow cytometry or a plate reader to measure the resulting reporter protein expression level for each input concentration.

- Data Analysis: Fit the dose-response data to a Hill function. The relative input range is the ratio of the input concentration at 90% of the maximum output to the concentration at 10% of the maximum output. The output fold-induction is the ratio of the maximum to the minimum output level. The utility is the product of these two values [2].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Optimized Sensor Circuits

| Sensor Type | Circuit Topology | Key Tuning Strategy | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Utility Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (OxyR) | Open-Loop | High-copy constitutive OxyR expression | 23.6 | 63.0 | 1,486.8 |

| Paraquat (SoxR) | Open-Loop | Low, IPTG-tuned SoxR expression | Not Specified | Not Specified | 11,620.0 |

Protocol: Implementing a Crosstalk-Compensation Circuit

This protocol describes a network-level solution to mitigate crosstalk between two sensor pathways [2].

- Objective: To design a dual-sensor strain that compensates for crosstalk by integrating signals from both sensors.

- Methodology:

- Crosstalk Quantification: Build a dual-sensor strain with two different reporters (e.g., sfGFP for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and mCherry for paraquat). Expose it to each input signal individually and in combination to map the degree of non-cognate activation.

- Circuit Design: Design a compensation circuit where the output from the sensor affected by crosstalk is adjusted by the output from the sensor that detects the interfering input. This creates an integrated network that computationally cancels out the crosstalk.

- Validation: Test the new circuit with combined inputs. The output for each specific signal should show reduced influence from the non-cognate input [2].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Growth Feedback on Circuit States

The following diagram illustrates how growth feedback differentially affects two common bistable circuit topologies.

Crosstalk Compensation Network

This diagram shows the logical design of a network that compensates for crosstalk instead of insulating against it.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Growth Feedback and Noise

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Repressive Links / Toggle Switches [10] [11] | Circuit topology for robust memory. Uses mutual repression to maintain bistable states under growth-mediated dilution. | More robust than self-activation switches. Can be designed with repressors like TetR and LacI. |

| NCR Antithetic Controller [12] | Multi-module control for noise reduction. Employs two antisense RNAs that co-degrade, effectively reducing noise from resource competition. | Superior performance in reducing anti-correlated fluctuations compared to local or global controllers. |

| Orthogonal Resource Systems [12] | Reduces inter-module coupling. Provides dedicated pools of ribosomes or RNA polymerases for synthetic circuits, minimizing resource competition. | Increases design complexity but can significantly improve modularity and predictability. |

| Burden-Responsive Promoters [11] | Implements negative feedback. A host promoter activated by stress/load represses synthetic gene expression, stabilizing growth and output. | Stabilizes output at the cost of reduced protein production yield. |

| Sensor Circuit Tuning (OxyR/SoxR) [2] | Optimizes analog sensor performance. Modulating transcription factor expression levels (e.g., with IPTG-tuned promoters) maximizes utility. | Critical for achieving high dynamic range and fold-induction in quantitative sensing applications. |

| Wilfordine | Wilfordine, MF:C43H49NO19, MW:883.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kudinoside D | Kudinoside D, MF:C47H72O17, MW:909.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

FAQ 1: How can I reduce crosstalk between my synthetic genetic circuit and the host's native regulatory networks?

Problem: Unwanted interactions between a synthetic circuit and the host genome cause unpredictable behavior, such as off-target gene expression or metabolic burden, reducing circuit performance.

Solution: Implement orthogonal biological parts that do not interact with the host's native systems [7].

- Use Orthogonal Regulators: Employ transcription factors (TFs) from distantly related species (e.g., bacterial TFs in plant or mammalian cells) [7]. CRISPR-dCas9 systems with custom guide RNAs offer high programmability and orthogonality [13] [14].

- Employ Synthetic σ/Anti-σ Factor Pairs: These pairs can create highly orthogonal operational amplifiers for signal processing, minimizing interference with host RNA polymerase [6].

- Select an Appropriate Chassis: Choose a host organism with well-characterized genetics. For complex circuits, consider using minimal genome strains that reduce native complexity and potential interference [13].

Experimental Protocol: Testing for Crosstalk

- Construct Control Circuits: Build circuits where the output of a synthetic promoter is measured both in the presence and absence of the putative orthogonal regulator.

- Quantify Leakiness: Measure baseline expression (e.g., fluorescence without inducer) of your circuit in the host using flow cytometry or microplate readers.

- Assess Specificity: Activate your circuit and use RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) or targeted RT-qPCR to monitor changes in host gene expression. Significant changes in non-target genes indicate crosstalk.

- Compare Hosts: Repeat the experiment in different chassis (e.g., different E. coli strains) to identify the most insulated environment [13].

FAQ 2: My genetic circuit's output is noisy and inconsistent. How can I improve its signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range?

Problem: High cell-to-cell variability (noise) in gene expression obscures the circuit's output signal, making it difficult to interpret results reliably.

Solution: Utilize circuit architectures that stabilize output and amplify the signal.

- Implement Negative Feedback: Design a circuit where the output product represses its own production pathway. This dampens internal noise and stabilizes the output level [6].

- Incorporate Signal Amplifiers: Synthetic biological operational amplifiers (OAs) can be built using orthogonal σ/anti-σ pairs. Tuning the ribosome binding site (RBS) strength allows you to control the amplifier's gain, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio [6].

- Use Robust Promoters: Characterize and select promoters with low intrinsic noise. Libraries of well-characterized, standardized promoters (e.g., from the Registry of Standard Biological Parts) can provide more predictable performance [15].

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Circuit Performance

- Clone Circuit Variants: Build circuit designs with and without feedback loops and with different RBS strengths controlling amplifier components [6].

- Measure Single-Cell Outputs: Use time-lapse fluorescence microscopy or high-throughput flow cytometry to measure output in hundreds to thousands of individual cells over time.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculate as the mean output in the "ON" state divided by the standard deviation of the output in the "OFF" state.

- Dynamic Range: Calculate as the ratio between the maximum ("ON") and minimum ("OFF") mean output levels.

- Compare Distributions: Analyze the data to determine which circuit design yields a tighter, more distinct distribution of "ON" and "OFF" states, indicating lower noise and better performance [13] [6].

FAQ 3: How can I design a circuit that responds specifically to a complex biological signal, like a particular growth phase?

Problem: Many biological signals, such as those marking the transition from exponential to stationary growth phase, are non-orthogonal, meaning multiple inputs can activate the same promoter, leading to lack of specificity.

Solution: Decompose the complex signal into orthogonal components using a synthetic biological operational amplifier (OA) framework [6].

- Design an Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) Circuit: This circuit processes multiple input signals (e.g., from growth-phase-responsive promoters) and performs linear operations (subtraction, scaling) to generate a unique, orthogonal output for the desired condition.

- Matrix-Based Design: Model the input signals as vectors and design a coefficient matrix that, when applied, diagonalizes the signal, isolating the component of interest.

Experimental Protocol: Decomposing Growth-Phase Signals

- Identify Input Promoters: Select two promoters, P1 and P2, with known but overlapping activities during exponential and stationary growth phases [6].

- Construct the OA Circuit: Build a circuit that performs the operation α·P1 - β·P2. The activators and repressors can be orthogonal σ factors and their cognate anti-σ factors. Tune parameters α and β by varying the RBS strengths of the activator and repressor [6].

- Calibrate the System: Measure the activity of P1 and P2 individually throughout the growth cycle in your host organism.

- Validate Specificity: Test the OST circuit output. A successfully designed circuit will show high output only during the specific growth phase targeted by the decomposition, and low output at all other times [6].

FAQ 4: What strategies can I use to create a stable, long-lasting memory device in a living cell?

Problem: Transient expression systems lose information once the inducing signal is removed, which is unsuitable for applications that require recording past events.

Solution: Engineer permanent, DNA-level changes using site-specific recombinases or CRISPR-Cas based recorders [13] [14].

- Recombinase-Based Memory: Use serine integrases (e.g., Bxb1, PhiC31) or tyrosine recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp) to invert or excise DNA segments. This physically alters the circuit's DNA, creating a permanent and heritable record of a signal event [13] [14].

- CRISPR-Cas Memory: Employ Cas1-Cas2 integrase systems to sequentially incorporate DNA spacers into a CRISPR array upon signal detection, creating a chronological record of events [14].

Experimental Protocol: Building a Recombinase-Based Memory Switch

- Construct the Memory Module: Clone a promoter driving the expression of a recombinase (e.g., Cre). Place a terminator or an inverted coding sequence for a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) between two recombinase recognition sites (e.g., loxP sites) [14].

- Integrate into Host: Stably integrate this construct into the host genome.

- Induce and Record: Expose the cells to the input signal that triggers the promoter, expressing the recombinase. The recombinase will catalyze the inversion or excision of the DNA between the recognition sites.

- Read the Memory: The permanent DNA rearrangement will lead to a stable change in reporter gene expression (e.g., turning ON GFP). This state is inherited by all daughter cells, even after the original signal is gone [13] [14].

Quantitative Data Tables for Circuit Design

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifiers (OAs)

This table summarizes key parameters for tuning OA circuits to optimize signal processing and reduce noise [6].

| Parameter | Definition | Impact on Circuit Function | Tuning Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain (O_max) | Maximum output level of the amplifier. | Determines the amplitude of the output signal. | Modify the binding strength of the activator to the output promoter [6]. |

| Binding Coefficient (Kâ‚‚) | Activator concentration at half-maximal output. | Defines the linear range of the circuit's response. A higher Kâ‚‚ extends the linear range [6]. | Engineer the promoter sequence or the DNA-binding domain of the activator [6]. |

| Bandwidth | The range of input signal frequencies the circuit can process with minimal error. | Determines how quickly the circuit can respond to changing signals. | Affected by degradation rates of circuit components (γâ‚, γ₂). Faster degradation can increase bandwidth [6]. |

| RBS Strength (r) | Translation initiation rate of activator/repressor. | Directly sets coefficients α and β in the OA operation α·X₠- β·X₂ [6]. | Use libraries of synthetic RBSs with varying predicted strengths [6]. |

Table 2: Stability and Thresholds of Sensing Circuits in Engineered Living Materials

This table provides experimental data on the performance of genetic circuits embedded in material scaffolds, highlighting their stability and operational ranges [16].

| Stimulus Type | Input Signal | Host Organism | Material Scaffold | Detection Threshold | Reported Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Pb²⺠| B. subtilis | Biofilm@biochar | 0.1 μg/L | >7 days [16] |

| Cu²⺠| B. subtilis | Biofilm@biochar | 1.0 μg/L | >7 days [16] | |

| Hg²⺠| B. subtilis | Biofilm@biochar | 0.05 μg/L | >7 days [16] | |

| Synthetic Inducer | IPTG | E. coli | Hydrogel | 0.1–1 mM | >72 hours [16] |

| Theophylline | S. elongatus | Hydrogel | ~0.5 mM | >7 days [16] | |

| Light | Blue Light (470 nm) | S. cerevisiae | Bacterial Cellulose | N/A | >7 days [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Host-Circuit Interactions

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Regulator Pairs | ECF σ/anti-σ factors [6], T7 RNAP/T7 lysozyme [6], Bacterial Transcription Factors (e.g., TetR, LacI) [7] | Core components for building circuits with minimal crosstalk to the host genome. Enable linear signal processing and amplification [6] [7]. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Serine Integrases (Bxb1, PhiC31) [14], Tyrosine Recombinases (Cre, Flp, FimE) [13] [14] | Create permanent, DNA-level memory of past events. Used for building logic gates and state-switching devices [13] [14]. |

| Programmable DNA-Binding Systems | CRISPR-dCas9 fused to activator/repressor domains [13] [14] | Provide highly programmable and orthogonal transcriptional control. Allow for epigenetic silencing (CRISPRoff/on) and logic operations [14]. |

| Standardized Genetic Parts | BioBricks from the Registry of Standard Biological Parts [15] | Pre-characterized promoters, RBSs, and terminators that facilitate modular, predictable, and reproducible circuit construction [15]. |

| Chassis Engineering Tools | Minimal genome strains, Protease-deficient strains | Host organisms engineered to reduce native complexity, degradation of synthetic parts, and overall metabolic burden, improving circuit predictability and stability [13]. |

| trans-Feruloyl-CoA | trans-Feruloyl-CoA, CAS:142185-30-6, MF:C31H44N7O19P3S, MW:943.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| aspergillusidone F | aspergillusidone F, MF:C19H16Br2O5, MW:484.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Circuit Diagrams

Orthogonal Signal Transformation Workflow

This diagram visualizes the experimental workflow for decomposing complex biological signals using synthetic operational amplifiers.

Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifier Design

This diagram illustrates the internal architecture of a synthetic biological operational amplifier (OA) used for precise signal processing.

CRISPR-dCas9 Transcriptional Control

This diagram shows how CRISPR-dCas9 systems can be used for orthogonal transcriptional control of synthetic gene circuits.

In synthetic biology, emergent dynamics are complex behaviors that arise from the interaction of simpler genetic components within a living cell. A fundamental challenge in this field is that these dynamics cannot always be predicted from circuit design alone, as they are significantly influenced by the cellular context and unintended interactions with the host [17]. This technical support guide focuses on two key emergent behaviors—bistability and trimodality—that frequently arise from feedback loops in synthetic gene circuits.

Bistability describes a system with two stable steady states, allowing a genetically identical cell population to sustain two distinct expression profiles. This phenomenon serves as the foundation for cellular memory devices and decision-making systems [18] [19]. When engineers observe unexpected bimodal expression patterns or difficulties in switching states, they are likely encountering bistable behavior. Similarly, trimodality extends this concept to three stable states, enabling more complex computational capabilities in engineered cells.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for mitigating noise and crosstalk—two significant obstacles in reliable circuit implementation. Noise refers to unwanted variability in gene expression, while crosstalk occurs when circuit components unintentionally interact with host systems or other synthetic parts. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting approaches to help researchers distinguish designed emergent behaviors from problematic experimental artifacts, ultimately advancing the construction of robust, predictable biological systems.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My synthetic toggle switch circuit shows unexpected bimodal expression instead of uniform response. Is this a design flaw or expected behavior? Bimodal expression is often the intended behavior in toggle switches, not necessarily a flaw. The co-repressive topology of a toggle switch, where two genes mutually repress each other, is classically known to generate bistability [17] [18]. This creates two stable states where each strain or cell population exclusively expresses one gene while repressing the other. Before troubleshooting, verify if your circuit design incorporates mutual repression. If confirmed, use time-lapse microscopy to track single cells and confirm state inheritance, which distinguishes true bistability from transient noise.

FAQ 2: I observe growth retardation in my engineered cells when my genetic circuit is activated. How does this affect circuit function? Circuit-induced growth retardation is a documented phenomenon that can significantly modulate circuit dynamics. Research on an auto-activating T7 RNA polymerase circuit demonstrated that growth retardation creates an emergent positive feedback loop on circuit components through reduced dilution effects [19]. This interaction can generate unexpected bistability even in circuits without cooperative regulation. To troubleshoot:

- Measure and compare growth rates of ON and OFF populations.

- Incorporate growth rate measurements into your mathematical models.

- Consider using orthogonal expression systems that minimize resource competition with host machinery.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish true trimodality from experimental noise in my population-level data? Distinguishing trimodality from noise requires single-cell resolution and temporal tracking:

- Use flow cytometry with appropriate controls to establish baseline noise levels.

- Employ time-lapse microscopy to track lineages and verify that all three expression states are stable and heritable across multiple cell divisions.

- Perform statistical analysis on distribution data; trimodal distributions will show three distinct peaks that persist over time, while noise appears as transient, non-heritable variations.

FAQ 4: What strategies can reduce crosstalk in complex genetic circuits with multiple feedback loops? Implementing orthogonality is the primary strategy for crosstalk mitigation. This involves using genetic components that interact strongly with intended partners but minimally with host systems and other synthetic parts [7]. Effective approaches include:

- Using bacterial transcription factors in mammalian systems to avoid interference with endogenous networks [7].

- Employing orthogonal σ/anti-σ factor pairs and RNA polymerase systems [6].

- Implementing operational amplifier-inspired circuits that linearly process signals to decompose overlapping inputs [6].

FAQ 5: My oscillator circuit produces irregular pulses instead of regular oscillations. What could be causing this? Irregular oscillations often stem from incorrect coupling between circuit dynamics and population dynamics. In microbial consortia, oscillations require precise tuning where growth rates depend on transcriptional states, creating an additional feedback loop [17]. Troubleshoot by:

- Verifying that growth rate differences between strains or states are sufficient to sustain oscillations.

- Checking for unintended metabolic burden that may desynchronize the population.

- Ensuring proper spatial mixing if using consortia, as localized signaling can disrupt temporal patterns.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Validating Bistability

Problem: Unconfirmed bistable behavior in a positive feedback circuit.

Background: Bistability creates two stable expression states maintained through positive feedback or mutual repression. Validation requires demonstrating hysteresis and state inheritance.

Experimental Protocol:

- Hysteresis Test: Gradually induce your circuit across a concentration range, then gradually de-induce. A bistable system will show different induction/de-induction thresholds.

- Single-Cell Lineage Tracking:

- Use microfluidics or time-lapse microscopy to track cells expressing a fluorescent reporter.

- Classify initial cell states as OFF, Intermediate (INT), or ON based on fluorescence.

- Monitor microcolonies originating from single cells for 3-6 hours under constant induction.

- Expected Outcome: Colonies from OFF cells remain predominantly OFF; ON colonies remain ON; INT colonies may bifurcate [19].

- State Stability Validation:

- Sort populations into OFF and ON subpopulations using FACS.

- Culture both subpopulations without induction for 4 hours to reset expression.

- Re-induce and monitor for 8 hours.

- Expected Outcome: Both subpopulations should return to similar bimodal distributions, confirming functional circuits in both states [19].

Interpretation: True bistability shows state inheritance and hysteresis. If not observed, check for insufficient feedback strength or high noise overwhelming the bistable region.

Guide 2: Resolving Unintended Emergent Dynamics

Problem: Circuit exhibits unexpected dynamics not accounted for in design.

Background: Synthetic circuits interact with host physiology, potentially creating emergent behaviors. A documented case showed non-cooperative auto-activation generating bistability through growth modulation [19].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Correlate Circuit Activity with Growth:

- Track single-cell growth rates (e.g., by cell division time or biomass accumulation) alongside fluorescence.

- Compare average growth rates of OFF, INT, and ON subpopulations.

- Expected Result: ON cells typically show slower growth (e.g., 0.18/hr vs 0.47/hr for OFF cells) if resource competition exists [19].

- Model with Growth Coupling:

- Expand mathematical models to include growth rate dependence on circuit activity.

- Account for nonlinear dilution of circuit components due to growth variation.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Use weaker promoters or ribosome binding sites to reduce metabolic burden.

- Implement resource-aware design principles that account for host capacity.

- Consider orthogonal chassis systems with minimized native interference.

Interpretation: If growth rate correlates with circuit activity, host modulation likely contributes to emergent dynamics. Model refinement incorporating these effects improves predictability.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Parameters

Key Parameters in Bistable Systems

Table 1: Experimentally measured parameters in synthetic bistable systems

| Parameter | System Description | Measured Values | Bistability Requirement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate Modulation | T7 RNAP* auto-activation | OFF: 0.47/hr, INT: 0.36/hr, ON: 0.18/hr | >20% difference between states | [19] |

| Cooperativity | T7 RNAP* transcription | Hill coefficient ≈ 0.99 | Not required for bistability | [19] |

| Population Ratio Dynamics | Co-repressive consortium | Logistic equation: ṙ = (β₠- β₂)r(1-r) | Dependent on growth rate difference | [17] |

| Repression Threshold | Co-repressive toggle | Half-maximal repression parameter θ | Proper spacing between switch thresholds | [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents for analyzing emergent dynamics

| Reagent/Circuit Type | Key Function | Example Components | Utility in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auto-activation Circuit | Tests positive feedback | Mutant T7 RNAP*, PT7 promoter, LacI/IPTG system | Validates hysteresis and growth modulation effects [19] |

| Co-repressive Toggle | Creates mutual exclusion | Orthogonal quorum sensing (cinI/R, rhlI/R), repressors | Demonstrates population-level bistability [17] |

| Operational Amplifier (OA) | Signal decomposition | σ/anti-σ pairs, RBS libraries, T7 RNAP/lysozyme | Mitigates crosstalk in multi-signal systems [6] |

| Recombinase-Based Switch | DNA-level memory | Tyrosine/serine recombinases (Cre, Flp, Bxb1), recognition sites | Creates stable, inheritable states with minimal energy [14] |

| Orthogonal σ/anti-σ Systems | Crosstalk mitigation | ECF σ factors, anti-σ factors | Provides insulation from host regulatory networks [6] |

Visualization of Core Concepts

Regulatory Topologies and Emergent Dynamics

This diagram illustrates three fundamental network architectures that can produce bistability. The positive feedback loop enables self-sustaining activation, while mutual repression creates exclusive states. Critically, growth-mediated feedback demonstrates how unintended host interactions can generate emergent bistability through reduced dilution of circuit components.

Experimental Workflow for Bistability Validation

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for confirming bistable behavior. The process begins with population-level screening using flow cytometry, followed by critical single-cell validation through time-lapse microscopy and hysteresis assays. This multi-scale approach distinguishes true bistability from transient noise or population heterogeneity.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Operational Amplifiers for Noise Mitigation

Recent advances in synthetic biological operational amplifiers (OAs) provide powerful tools for mitigating noise and crosstalk. These circuits implement mathematical operations of the form α·X₠- β·X₂ to decompose non-orthogonal biological signals into distinct components [6]. By engineering σ/anti-σ pairs and tuning RBS strengths, researchers can create OA circuits that enhance signal-to-noise ratios and enable precise orthogonal control over multiple pathways simultaneously. This approach is particularly valuable for constructing growth-phase-responsive systems without external inducers and for resolving multi-dimensional crosstalk in complex genetic networks.

Engineered Living Materials and Biosensing

The integration of synthetic genetic circuits with material science has enabled the development of engineered living materials (ELMs) with sophisticated sensing capabilities [16]. These systems embed genetic circuits within microbial consortia encapsulated in synthetic matrices, creating responsive materials that detect environmental signals. For such applications, bistable switches and feedback loops provide crucial signal processing functions, enabling digital-like responses to analog environmental inputs. Implementation requires careful consideration of matrix properties, nutrient diffusion, and long-term circuit stability to maintain predictable emergent behaviors outside laboratory conditions.

Engineering Solutions: Orthogonal Systems, Signal Processing, and Insulation Strategies

FAQs: Orthogonality in Genetic Circuit Design

What is "crosstalk" in synthetic genetic circuits? Crosstalk occurs when components of a synthetic genetic circuit, such as transcription factors, regulators, or signals, unintentionally interact with or interfere with multiple parts of the system. For example, a transcription factor designed to regulate one gene might also bind to and activate another, unintended promoter. This faulty wiring introduces noise, reduces circuit predictability, and can lead to functional failure. Minimizing crosstalk is thus crucial for building robust, complex circuits [13].

How does using "heterologous parts" promote orthogonality? Heterologous parts are biological components (like promoters, ribosome binding sites, or coding sequences) derived from a different species than the host organism. Their key advantage is orthogonality—they are designed to function as intended within the host without interacting with the host's native systems or with other, unrelated synthetic parts. Using a library of heterologous parts from diverse origins allows designers to create multiple, independent circuit pathways within a single cell that do not interfere with one another, thereby minimizing crosstalk [13].

What are the main sources of crosstalk in a circuit, and how can I identify them? The main sources include:

- Resource Competition: Shared cellular resources, like RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and nucleotides, can lead to unexpected coupling between seemingly independent circuit modules.

- Regulator Lack of Specificity: A regulator (e.g., a transcription factor) may not be fully specific to its target promoter or binding site.

- Metabolic Burden: High expression from a synthetic circuit can burden the host cell, indirectly affecting the function of other circuits. Identification often requires careful characterization. You can screen for crosstalk by measuring the output of your "victim" circuit module when the suspected "aggressor" module is activated, even in the absence of its designed input.

My circuit is not producing the expected output. Could crosstalk be the cause? Yes. Unpredictable or "leaky" expression, low signal-to-noise ratios, and failure to achieve desired dynamic behaviors (like oscillations or switches) are common symptoms of underlying crosstalk. Before assuming a complete design flaw, it is essential to systematically test for unintended interactions between your circuit's components [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background Noise or Leaky Expression

Potential Cause: Insufficient orthogonality of regulatory parts. The transcription factor or regulatory protein may be binding weakly to non-cognate promoters.

Solutions:

- Use Orthogonal Regulators: Replace standard parts (like LacI, TetR) with more specialized, heterologous regulators from a curated library. Recent efforts have significantly expanded the number of available orthogonal DNA-binding proteins (e.g., Zinc Finger Proteins, TALEs, CRISPR-dCas9) for this purpose [13].

- Characterize and Tune Parts: Use computational tools to model and predict interaction strengths. Experimentally, you can fine-tune the expression levels of your regulators or mutate their binding sites to improve specificity and reduce off-target binding [13].

- Employ CRISPRi/a: Use catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor or activator domains. The high specificity of guide RNA-DNA binding can provide superior orthogonality compared to some traditional repressors [13].

Problem: Unintended Circuit Activation

Potential Cause: Signal transduction crosstalk, where a molecule or signal from one pathway activates a sensor in another, unrelated pathway.

Solutions:

- Implement Orthogonal Signal Systems: Utilize completely heterologous signal transduction systems. For instance, in engineered living materials, circuits can be designed to respond to synthetic inducers (like IPTG or aTc), specific light wavelengths, or other physical cues that do not naturally occur in the host's environment, ensuring they do not interfere with native processes [16].

- Physical Insulation: Increase the "spacing" between potentially interfering pathways. In genetic terms, this can mean using distinct, non-homologous genetic parts and ensuring that the regulatory elements for one circuit are not similar to those of another [20].

Problem: Unstable Circuit Performance or Loss of Function Over Time

Potential Cause: Resource competition and metabolic burden, leading to increased noise and evolutionary pressure to inactivate the circuit.

Solutions:

- Balance Resource Usage: Avoid overloading the host with high-copy plasmids or strong, constitutive promoters. Use "tuning knobs" such as ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering and promoter strength modulation to balance expression levels across all circuit modules, reducing competition for shared pools of ribosomes and polymerases [13].

- Use Orthogonal Hosts: In some cases, using a minimal or genomically recoded chassis can eliminate the possibility of crosstalk with native genes and free up cellular resources [13].

Experimental Protocols for Crosstalk Mitigation

Protocol 1: Characterizing Promoter-Transcription Factor Orthogonality

Objective: To quantitatively assess the specificity of a library of heterologous transcription factors (TFs) to their cognate promoters.

Materials:

- Plasmid Library: A set of plasmids, each containing a different TF gene under a controlled inducible promoter.

- Reporter Plasmids: A set of plasmids, each with a distinct reporter gene (e.g., GFP, RFP) driven by a promoter targeted by one of the TFs.

- Host Strain: An appropriate microbial host (e.g., E. coli).

- Inducers: Molecules to induce TF expression.

- Flow Cytometer or Plate Reader: For quantifying reporter output.

Procedure:

- Co-transform the host strain with one TF plasmid and one reporter plasmid, creating a matrix of all possible TF-reporter combinations.

- Grow colonies for each combination in triplicate.

- Induce TF expression using a standardized concentration of inducer.

- Measure the fluorescence intensity (reporter output) for each culture after a defined period of growth.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fold-change in expression for each TF on its cognate versus non-cognate promoters. A high signal on the cognate promoter with minimal signal on non-cognate promoters indicates good orthogonality.

Expected Outcome: A matrix of data that visually confirms which TF-promoter pairs are orthogonal and which exhibit significant crosstalk.

Protocol 2: Implementing an Orthogonal CRISPRi Gate

Objective: To construct a NOT logic gate using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) that is orthogonal to the host's transcriptional machinery.

Materials:

- dCas9 Gene: A gene for catalytically inactive Cas9, codon-optimized for your host.

- Guide RNA (gRNA) Scaffold: A DNA sequence for expressing the gRNA.

- Target Promoter: The promoter you wish to repress, driving a reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Inducible Promoter: A promoter to control the expression of the gRNA.

- Standard Molecular Biology Reagents: For DNA assembly and transformation.

Procedure:

- Construct the Circuit: Assemble a plasmid where the dCas9 is expressed constitutively. On a second plasmid (or a different location on the same plasmid), place the gRNA scaffold under the control of an inducible promoter (Input). Design the gRNA sequence to be complementary to a region within the target promoter (Output).

- Transform the circuit into your host organism.

- Test the Gate: Grow cultures with and without the inducer for the gRNA.

- Measure the output (e.g., GFP fluorescence).

- Verify Orthogonality: Confirm that the dCas9 and gRNA do not affect other, unrelated genes or circuits in the cell by measuring their expression in the presence of the induced CRISPRi system.

Expected Outcome: High GFP output in the absence of the inducer and low GFP output in the presence of the inducer, demonstrating specific repression without affecting other circuit components.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Orthogonal Genetic Circuit Construction

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example & Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal TFs & Promoters | Provides specific, non-cross-reacting transcriptional regulation. | Libraries of TetR-family repressors or synthetic σ factors/anti-σ factors for AND/NAND logic [13]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | Enables highly specific gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) via programmable RNA guides. | dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressor/activator domains; offers high designability and orthogonality via guide RNA sequence [13]. |

| Serine Integrases | Enables permanent, unidirectional DNA inversion for building memory elements and logic gates. | Phage-derived integrases (e.g., Bxb1, φC31); used to build memory circuits and complex logic by flipping DNA segments [13]. |

| Synthetic Inducers | Provides external, user-defined control over circuit activation, minimizing interaction with native cellular processes. | Chemicals like IPTG, aTc, or AHL; or physical signals like specific light wavelengths used in engineered living materials [16]. |

| Computational Design Tools | Aids in the in silico design, modeling, and prediction of circuit behavior and potential crosstalk. | Software like MATLAB/SimBiology or COPASI for simulating circuit dynamics and predicting resource competition [13]. |

Visualizing Orthogonality and Crosstalk

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of using heterologous parts to achieve orthogonality and minimize crosstalk.

Diagram 1: Orthogonal circuits with no crosstalk.

Diagram 2: Resource competition and transcriptional crosstalk.

Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifiers for Complex Signal Decomposition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of a synthetic biological operational amplifier (OA) in genetic circuits?

Biological OAs are engineered genetic devices designed to process complex, non-orthogonal cellular signals. Their primary function is to decompose mixed input signals—such as those originating from different growth phases or quorum sensing molecules—into distinct, orthogonal outputs. This is achieved through linear operations like weighted subtraction and amplification, implemented using orthogonal transcription factor pairs like σ/anti-σ factors or T7 RNAP and its inhibitor. The process enhances the signal-to-noise ratio and enables precise, dynamic control of gene expression without external inducers, which is crucial for advanced applications in metabolic engineering and biosensing [6] [21] [22].

Q2: My OA circuit is exhibiting a nonlinear response. What could be the cause?

A nonlinear response typically occurs when the effective activator concentration (XE) exceeds the linear operational range of the circuit. The output O is defined by the equation O = (O_max * X_E) / (K_2 + X_E), where K_2 is the activator binding constant. The relationship between XE and the output is linear only when X_E << K_2 [6]. To restore linearity:

- Adjust the Binding Affinity: Engineer the output promoter to have a larger

K_2value, thereby extending the linear range of operation. - Tune Circuit Gains: Modify the RBS strengths of the activator and repressor components to reduce the overall gain (

αandβ), ensuring that X_E remains within the linear window for your expected input signals [6].

Q3: How can I minimize crosstalk when processing multiple signals simultaneously?

To mitigate crosstalk in multi-signal systems, implement an Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) framework.

- Use Orthogonal Regulator Pairs: Employ multiple, highly orthogonal transcription factor pairs (e.g., different ECF σ/anti-σ pairs) that do not interact with each other or the host's native systems [6].

- Matrix-Based Design: Frame the signal decomposition as a matrix operation. Design your OA circuits to implement the coefficient matrix that will diagonalize the input signal matrix, ensuring that each output channel is independently controlled [6]. This approach has been successfully used to resolve crosstalk among three bacterial quorum-sensing signals [6] [22].

Q4: What strategies can reduce the metabolic burden on the host cell from OA circuits?

Host burden becomes significant as circuit complexity increases. Key strategies include:

- Limit Component Count: The practical number of dimensions

Nfor signal decomposition is limited by the availability of orthogonal regulatory pairs and the cumulative metabolic load. Start with simpler 2D systems before scaling up [6]. - Optimize Expression Levels: Fine-tune RBS strengths and promoter activities to express circuit components at the minimal levels required for function, avoiding unnecessary protein overexpression [6].

- Consider Insulation Modules: To further enhance modularity and reduce unintended interference (retroactivity) between connected circuits, incorporate insulation devices like phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles, which are known to attenuate load effects [23].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key quantitative data from the implementation of synthetic biological OAs in E. coli, as presented in the research [6] [21] [22].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifiers

| Performance Metric | Reported Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Signal Amplification | Up to 153-fold / 688-fold | Achieved in growth-stage-responsive circuits in E. coli [6] [21]. |

| Signal Decomposition Dimensionality | Resolved 3D signal crosstalk | Successfully orthogonalized three intertwined quorum-sensing signals into independent outputs [6] [22]. |

| Key Mathematical Operation | ( XE = α \cdot X1 - β \cdot X_2 ) | The core linear operation performed by the OA circuit on input signals X₠and X₂ [6]. |

| Application: Shikimic Acid Production | Inducer-free, autonomous switching | Cells autonomously switched metabolism to produce shikimic acid during the production phase, improving efficiency and cost [21] [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a Basic Open-Loop Biological OA Circuit

This protocol details the construction of a biological OA capable of performing the operation ( α \cdot X1 - β \cdot X2 ) [6].

1. Reagent Setup

- Activator (A) and Repressor (R) Plasmids: Create two input plasmids. The first plasmid places the gene for the Activator (A), such as an ECF σ factor or T7 RNAP, under the control of promoter Xâ‚. The second plasmid places the gene for the Repressor (R), such as the cognate anti-σ factor or T7 lysozyme, under the control of promoter Xâ‚‚.

- Output Reporter Plasmid: Construct a third plasmid containing an output promoter, which is strongly activated by the Activator (A) and repressed by the Repressor (R). This promoter drives the expression of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Tuning Elements: Incorporate synthetically designed RBS sequences with varying predicted strengths upstream of the Activator and Repressor genes.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Co-transform the three plasmids (Activator, Repressor, and Output) into your E. coli host strain.

2. Culture the transformed bacteria and expose them to conditions that trigger the input promoters Xâ‚ and Xâ‚‚.

3. Measure the resulting output signal (e.g., fluorescence) and the concentrations of the key internal components.

4. Characterize the Transfer Function: By varying the inputs Xâ‚ and Xâ‚‚ and measuring the output, map the circuit's transfer function to verify it performs the intended weighted subtraction.

5. Tune the Circuit: If the response is too weak or nonlinear, iterate by swapping the RBSs on the Activator and Repressor plasmids to adjust the translation rates r₠and r₂, thereby modifying the coefficients α and β [6].

3. Analysis and Troubleshooting

- Validation: Plot the output against the calculated

X_Eto check for linearity within the expected range. - Common Issue: High Output Leakage: If leakage is high when both inputs are off, check the specificity of your transcription factor pairs and consider using lower-leakage promoters or optimizing repressor binding.

Protocol: Implementing Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) for Crosstalk Mitigation

This protocol describes applying the OA framework to decompose a 2D non-orthogonal signal, such as overlapping exponential/stationary phase promoter activities [6].

1. Reagent Setup

- Input Sensors: Utilize promoters that respond to the conditions of interest (e.g., P{exp} and P{stat}) but exhibit overlapping activities.

- OA Circuit Library: Have a set of pre-characterized biological OA circuits ready, each with different, known

αandβcoefficients. - Orthogonal Reporters: Use distinct, orthogonal reporter genes (e.g., GFP, RFP, BFP) for each output channel to enable simultaneous measurement.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Characterize Input Promoters: Measure the activities of P{exp} and P{stat} individually and in combination under exponential and stationary growth conditions to establish the input signal matrix.

2. Define Target Matrix: Determine the desired orthogonal output matrix. Typically, this is a diagonal matrix where Output 1 is high only in the exponential phase and Output 2 is high only in the stationary phase.

3. Calculate Coefficient Matrix: Using the known input matrix and desired output matrix, compute the required coefficient matrix that transforms one into the other.

4. Select and Assemble OAs: Choose OA circuits from your library whose α and β parameters match the coefficients in the calculated matrix. Assemble the genetic circuits accordingly.

5. Validate the System: Test the complete OST circuit by measuring all outputs under exponential and stationary growth conditions. Confirm that the outputs are now orthogonalized, with minimal crosstalk.

3. Analysis and Troubleshooting

- Validation: Successful orthogonalization will show a strong, specific response in each output only to its target condition.

- Common Issue: Residual Crosstalk: If crosstalk persists, fine-tune the RBS strengths in your OA circuits or verify the orthogonality of your regulatory pairs. The matrix calculation might need adjustment for biological constraints, as negative values from operations are often set to zero [6].

Visualization of Core Concepts

OA Circuit Architecture and Workflow

Diagram Title: Biological OA Circuit Design and Signal Flow

Orthogonal Signal Transformation Matrix

Diagram Title: Signal Orthogonalization via Matrix Operation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Synthetic Biological OA Construction

| Research Reagent | Function in OA Circuits | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factor Pairs | Core components that perform linear activation and repression. | ECF σ/anti-σ factor pairs (e.g., from E. coli or other bacteria); T7 RNA Polymerase (T7 RNAP) and its inhibitor T7 lysozyme [6]. |

| Tunable Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS) | Fine-tunes the translation efficiency of activators and repressors, setting the coefficients α and β in the OA operation. |

A library of synthetic RBS sequences with varying predicted strengths to empirically adjust circuit parameters [6]. |

| Growth-Phase Responsive Promoters | Serves as input sensors for dynamic, inducer-free control circuits. | Native E. coli promoters with characterized activity profiles during exponential and stationary growth phases [6] [21]. |

| Quorum Sensing Systems | Provides complex, multi-dimensional input signals for demonstrating crosstalk mitigation. | Components of bacterial QS systems (e.g., Lux, Las, Rhl) that produce intertwined signaling molecules [6] [22]. |

| Reporters for Quantification | Enables measurement of input and output signals. | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP, BFP); enzymatic reporters; Broccoli fluorescent RNA aptamer for transcriptional readout [6] [24]. |

| 17-GMB-APA-GA | 17-GMB-APA-GA, MF:C39H53N5O11, MW:767.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PIN1 degrader-1 | PIN1 degrader-1, MF:C30H32Cl2N6O4, MW:611.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing Negative Feedback Control for Noise Reduction and Stability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main benefits of using negative feedback control in synthetic genetic circuits? Negative feedback is a fundamental control mechanism where a system's output is fed back in a way that reduces fluctuations and drives the output toward a desired set point. In synthetic gene circuits, it is primarily used to enhance robustness and reliability [25] [26]. Key benefits include:

- Noise Reduction: It suppresses variations in circuit output caused by both internal stochasticity (intrinsic noise) and external fluctuations (extrinsic noise), such as changes in cellular resource availability [25] [27].

- Increased Stability: It helps maintain consistent performance despite disturbances, such as changes in growth conditions or mutations, promoting a stable equilibrium [25] [11] [26].

- Evolutionary Longevity: Circuits with negative feedback can maintain function over more generations by reducing the cellular burden (growth disadvantage) associated with circuit expression, thereby slowing down the selection for non-functional mutant cells [28].

FAQ 2: My circuit's output is unstable. How can I diagnose where the problem is in the feedback loop? A feedback loop can be broken down into four core elements. Diagnosing faults involves checking the input and output of each element to identify where the expected relationship fails [29].

- 1. Decision-making (Controller): Check the controller (e.g., a repressor protein or sRNA). Is its production and activity appropriate given the current process variable (PV, e.g., output protein level) and the set point (SP)? If not, the problem may be with the controller's design or tuning [29].

- 2. Sensing (Measurement): Compare the actual process variable (verified by an independent method) with the value "seen" by the controller. A discrepancy indicates a fault in the sensing mechanism, such as a poorly characterized promoter or sensor [29].

- 3. Influencing (Actuation): Compare the controller's output signal (e.g., concentration of repressor) with the actual state of the final control element (e.g., the promoter it is supposed to regulate). If the actuator is not responding correctly to the controller, this is the source of the problem [29].

- 4. Reacting (Process): Determine if the process itself (e.g., gene expression and translation) is reacting as expected to the state of the actuator. If not, the issue may lie with the core process components, such as ribosome binding site strength or mRNA degradation rates [29].

FAQ 3: Should I use a transcriptional or post-transcriptional controller for negative feedback? The choice depends on your specific goals for performance and burden. The table below compares the two common strategies.

| Feature | Transcriptional Control (e.g., TF-based) | Post-Transcriptional Control (e.g., sRNA-based) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | A transcription factor (TF) represses its own promoter [25]. | A small RNA (sRNA) binds to and inhibits translation of the target mRNA [25]. |

| Speed | Slower, due to the time required for protein production and maturation [25]. | Faster, as it bypasses the protein production step and leverages rapid RNA degradation [25]. |

| Noise Profile | Can effectively suppress noise, but may increase noise if repression is too strong or weak [27]. | Does not typically result in large increases in noise; can filter extrinsic noise [25]. |

| Input-Output Response | Steep, sigmoidal response, allowing only coarse tuning [25]. | More linear response, enabling finer and more precise tuning of the output [25]. |

| Cellular Burden | Higher, due to the energy cost of producing regulatory proteins [25] [28]. | Lower, as sRNAs are faster and less costly for the cell to produce [25] [28]. |