Synthetic Consortia vs. Single Strains: A Comparative Analysis of Performance, Design, and Clinical Potential

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between synthetic microbial consortia and single-strain biotherapeutics for researchers and drug development professionals.

Synthetic Consortia vs. Single Strains: A Comparative Analysis of Performance, Design, and Clinical Potential

Abstract

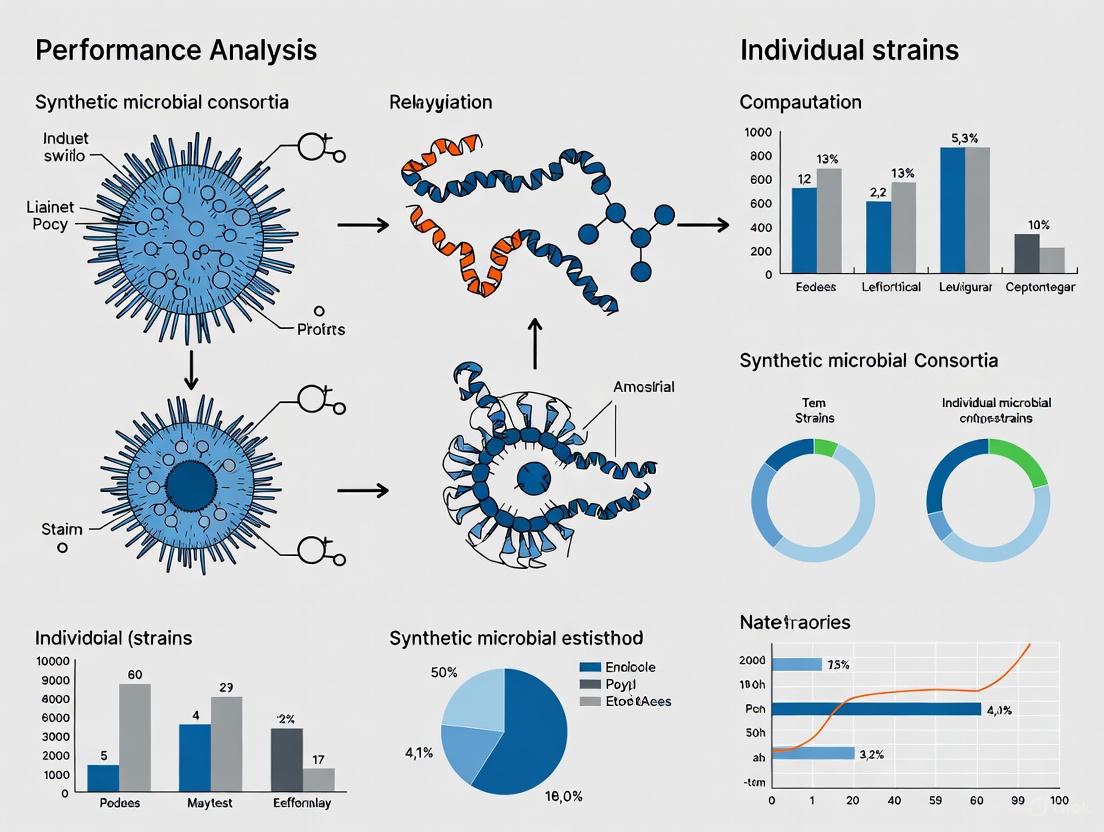

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between synthetic microbial consortia and single-strain biotherapeutics for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of microbial consortia, detailing how multi-strain systems outperform single strains in complex functions and environmental resilience. The content covers advanced methodological approaches, including synthetic biology tools and quorum-sensing communication modules, for constructing therapeutic consortia. It addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhancing consortium stability and efficacy, and presents rigorous validation data and comparative performance metrics from preclinical and clinical studies. The analysis synthesizes evidence supporting consortia's superior capabilities in drug production, bioremediation, and therapeutic applications while outlining future directions for clinical translation.

The Science of Synergy: Understanding Microbial Consortia Fundamentals

Synthetic microbial consortia represent a paradigm shift in biotechnology, moving beyond the constraints of single-strain approaches. These are artificially engineered or designed communities of multiple microorganisms where division of labor, spatial organization, and enhanced robustness enable complex functions unattainable by individual strains [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the performance of synthetic consortia against single-strain alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Consortia vs. Single Strains

Table 1: Biofertilization and Bioremediation Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Single-Species Inoculation | Microbial Consortium Inoculation | Reference Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Enhancement | 29% increase | 48% increase | Compared to non-inoculated treatments [3] |

| Pollution Remediation Effectiveness | 48% increase | 80% increase | Compared to non-inoculated treatments [3] |

| Overall Performance Advantage | Baseline | More significant | Advantage held across various conditions [3] |

| Field vs. Greenhouse Efficacy | Reduced efficacy | Reduced but retained significant advantage | Consortium maintains performance edge despite field challenges [3] |

Table 2: Functional and Robustness Advantages

| Characteristic | Single-Strain Systems | Synthetic Microbial Consortia | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | High on a single chassis | Distributed via division of labor | Reduced burden expands bioproduction capabilities [2] |

| System Robustness | More sensitive to perturbations | Increased resilience to environmental challenges | Sampling hypothesis & social interactions enhance stability [2] |

| Functional Complexity | Limited by host capacity | Expanded via combined capabilities | Enables complex metabolic pathways [1] [2] |

| Substrate Utilization | Limited to host metabolism | Can use complex, mixed substrates | Division of labor allows broader substrate spectrum [2] |

Core Experimental Protocols for Consortium Performance

Meta-Analysis of Live-Soil Studies

A global meta-analysis of 51 live-soil studies (from a pool of 2,149 studies) systematically quantified the effects of single-species versus consortium inoculation on biofertilization and bioremediation [3]. The protocol involved:

- Experimental Design: Comparing inoculated treatments (both single-species and consortium) with non-inoculated control treatments across multiple independent studies.

- Measurement Parameters: Quantifying percent increase in plant growth and pollution remediation.

- Condition Optimization: Identifying that increasing original soil organic matter, available nitrogen, and phosphorus content, while regulating soil pH to 6–7, achieved better inoculation effects [3].

Cross-Feeding Based Consortium Construction

This widely used construction principle creates synthetic microbial consortia based on metabolic interactions [4]. The methodology includes:

- Strain Selection: Choosing microbial strains with complementary metabolic capabilities (e.g., one degrades alkanes, another produces surfactants).

- Co-culture Establishment: Cultivating selected strains together under defined environmental conditions.

- Performance Validation: Measuring functional output (e.g., degradation rate of target pollutant) compared to single-strain systems. In one application, this approach yielded an 8.06% higher alkane degradation rate for a co-culture system of Acinetobacter sp. XM-02 and Pseudomonas sp. compared to the single degrading strain [4].

Engineered Communication Networks

This approach uses synthetic biology tools to program interactions between consortium members [2]:

- Sender-Receiver Engineering: A "sender" strain is engineered to synthesize a signaling molecule (e.g., acyl-homoserine lactone for Gram-negative bacteria), which diffuses and activates gene expression in a "receiver" strain engineered with the corresponding receptor/responsive promoter.

- Orthogonal Systems: Using multiple quorum-sensing systems (e.g., lux, las, rpa, tra) with minimal signal or promoter crosstalk to create independent communication channels.

- Behavioral Control: Linking communication systems to expression of functional genes, antibiotic resistance, or toxins to regulate population dynamics and consortium output.

Signaling Pathways and Engineering Workflows

Synthetic Consortium Communication Pathways

Diagram Title: Engineered Microbial Communication Pathway

Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle

Diagram Title: Consortium Engineering Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Consortium Engineering and Analysis

| Research Reagent | Category | Function & Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (HSL) | Signaling Molecules | Engineered quorum sensing communication between Gram-negative strains [2] | Activate gene expression in receiver strains via concentration-dependent sensing |

| Orthogonal Inducers (IPTG, aTc) | Gene Expression Regulators | Exogenous control of transgene expression with minimal crosstalk between circuits [2] | Independently regulate different genetic pathways distributed across consortium members |

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Genetic Engineering Tools | Efficient gene deletions, insertions, and transcriptional control in consortium members [2] | Modify metabolic pathways or install communication modules in diverse microbial chassis |

| Synthetic Promoter Libraries | Genetic Parts | Enable orthogonal gene regulation and circuit construction across strains [2] | Build responsive genetic circuits that function predictably in different microbial hosts |

| Microfluidics & Optogenetics Platforms | Validation Tools | Enable precise spatial and temporal control for in-vivo validation of consortium dynamics [5] | Test and optimize consortium interactions in controlled environments mimicking natural conditions |

| 2'-Deoxyisoguanosine | 2'-Deoxyisoguanosine Supplier|CAS 106449-56-3 | Bench Chemicals | |

| 11(R)-Hepe | 11(R)-Hepe, CAS:109430-11-7, MF:C20H30O3, MW:318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Synthetic microbial consortia demonstrate clear quantitative advantages over single-strain approaches, with consortium inoculation providing 48% improvement in plant growth and 80% enhancement in pollution remediation compared to non-inoculated treatments—significantly outperforming single-species inoculation [3]. The field is advancing through computational modeling that shifts focus from individual organisms to functional modules within communities [1], supported by engineering strategies that program communication networks and metabolic interactions [2] [4]. For researchers in drug development and biotechnology, synthetic consortia offer a powerful platform for applications ranging from targeted drug delivery to sustainable bioproduction, overcoming fundamental limitations of single-strain systems through distributed function and enhanced resilience.

The application of beneficial microorganisms is a established strategy for enhancing plant growth and resilience. For years, the primary approach has relied on single-strain inoculants, selected for specific plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits. However, the challenge of achieving consistent and reproducible results under diverse, real-world field conditions has prompted a shift in research and application. Scientists are increasingly exploring the use of designed microbial consortia, which comprise multiple, compatible strains with diverse functional roles. This guide provides a quantitative comparison of the performance of microbial consortia against single-strain inoculants, synthesizing evidence from meta-analyses and controlled experiments to inform research and development in agricultural biotechnology and beyond.

A global meta-analysis of 51 live-soil studies provides the most comprehensive quantitative overview of the performance differential between the two approaches. The analysis systematically compared the impact of single-species and consortium inoculations on key agricultural outcomes [3] [6]. The table below summarizes the findings.

Table 1: Performance Summary from Global Meta-Analysis

| Performance Metric | Single-Strain Inoculants | Microbial Consortia | Comparison to Non-Inoculated Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Promotion | 29% increase | 48% increase | Consortium effect >1.6x that of single strains |

| Pollution Remediation | 48% increase | 80% increase | Consortium effect >1.6x that of single strains |

| Contextual Efficacy | Reduced efficacy in field settings | Maintained a more significant overall advantage under various conditions | Consortia show greater reliability and flexibility |

The meta-analysis identified that the diversity of inoculants and synergistic effects between commonly used microbes like Bacillus and Pseudomonas are significant contributors to the enhanced performance of consortia [3].

Detailed Experimental Comparisons and Protocols

To move beyond broad averages, it is critical to examine performance in specific experimental contexts, which reveal how environmental conditions and management practices influence outcomes.

Case Study I: Greenhouse vs. Open-Field Tomato Production

A direct comparative study investigated the efficiency of single-strain versus consortium products in two distinct tomato production systems [7].

Table 2: Experimental Conditions and Yield Impact

| Experimental Parameter | Case Study I: Greenhouse (Romania) | Case Study II: Open-Field (Israel) |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Type | Clay loam Vertisol, pH 7.1 | Alkaline sandy soil, pH 7.9 |

| Fertilization | Organic (composted manure, guano, hair/feather meal) | Mineral fertilization, low native P availability |

| Environmental Challenge | Standard protected cultivation | High pH, low fertility, desert climate |

| Single-Strain Performance | Significant improvement (39-84% yield increase vs. control) | Limited |

| Consortium (MCP) Performance | Similar beneficial effects to single strains | Superior performance in P acquisition, shoot biomass, and final fruit yield |

3.1.1 Experimental Protocol: Tomato Cultivation & Inoculation [7]

- Plant Material & Growth Conditions:

- Tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) variety Primadona F1 was used.

- Greenhouse (Romania): Nursery plants were grown in a compost-based substrate and later transplanted into a greenhouse soil amended with organic fertilizers (guano, feather meal).

- Open-Field (Israel): Plants were grown in a drip-fertigated system on a high-pH, low-fertility sandy soil with band placement of mineral P fertilizer.

- Microbial Inoculants: The study tested selected fungal and bacterial single-strain inoculants with known PGP potential versus commercial microbial consortium products (MCPs).

- Inoculation Method: In the open-field system, microbial inoculants were applied directly via the fertigation system.

- Data Collection:

- Vegetative Growth: Shoot biomass production was measured.

- Yield: Final fruit yield was harvested and weighed.

- Nutrient Acquisition: Plant P content was analyzed.

- Rhizosphere Analysis: Bacterial community structure at the root surface (rhizoplane) was analyzed using molecular techniques (e.g., 16S rRNA gene sequencing).

Case Study II: Drought Stress Protection in Potato

A study on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under drought stress further highlights the context-dependent advantage of consortia and the critical influence of nitrogen form [8].

3.2.1 Experimental Protocol: Potato Drought Stress [8]

- Plant Material & Growth Conditions:

- Potato cv. Alonso was used in both greenhouse and field trials.

- Pre-germinated tuber pieces with sprouts were planted in pots (greenhouse) or directly in the field.

- Drought Stress: A 70% reduction in water supply was imposed over six weeks in greenhouse trials. Field trials included irrigated and non-irrigated conditions.

- N Fertilization: Plants were supplied with either NO₃⻠(nitrate) or NH₄⺠(ammonium)-dominated fertilizers.

- Microbial Inoculants: Six fungal/bacterial single-strain inoculants and ten consortia were tested, including an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF), Rhizophagus irregularis.

- Inoculation Method: Microbial strains were maintained on specific agar media and applied to the plants during the growth period.

- Data Collection:

- Growth & Yield: Shoot biomass, tuber biomass, and tuberization.

- Physiological Status: Nutritional status (P concentration), irreversible leaf damage, osmotic adjustment (glycine betaine accumulation).

- Stress Signaling: Concentrations of stress hormones (Abscisic Acid-ABA, Jasmonic Acid, Indole Acetic Acid) in shoots.

- Oxidative Stress: Enzymatic detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental design for this case study.

Diagram: Experimental workflow for potato drought stress study.

3.2.2 Key Findings on Performance [8]

- Under NO₃⻠fertilization, drought stress severely reduced tuber biomass by 50%. While several single-strain and consortium inoculants improved the plant's P nutritional status and reduced leaf damage, none mitigated the tuber yield loss.

- Under NHâ‚„âº-dominated fertilization, tuber biomass under drought stress increased dramatically (534% vs. NO₃⻠control). Additional inoculation with AMF further increased this yield benefit to 951%.

- The NH₄⺠+ AMF combination enhanced drought tolerance by:

- Improving enzymatic ROS detoxification.

- Supporting osmotic adjustment (glycine betaine).

- Modulating stress signaling hormones (ABA, JA, IAA) linked to tuberization.

- Adding bacterial inoculants to the AMF further improved antioxidant production but could divert energy to shoot growth at the expense of tubers, demonstrating the need for careful consortium design.

The diagram below summarizes the stress response pathways activated by the successful NH₄⺠+ AMF treatment.

Diagram: Drought stress response pathways with NHâ‚„âº+AMF.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential biological materials and their functions, as used in the featured experiments [7] [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Type / Species | Key Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Rhizophagus irregularis | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus (AMF) | Enhances phosphate uptake, improves water stress tolerance, and modulates plant hormone signaling. |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Bacterial Single-Strain (e.g., FZB42) | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR); produces antibiotics, solubilizes phosphate, produces phytohormones. |

| Pseudomonas brassicacearum | Bacterial Single-Strain (e.g., 3Re2-7) | PGPR; can improve plant fitness under stress, potentially via phytohormone production or niche competition. |

| SynComs (Synthetic Communities) | Designed Microbial Consortia | Multi-strain mixtures designed for complementary functions (e.g., P-solubilization, N-fixation, pathogen suppression) to increase resilience and efficacy. |

| Kings B Medium | Bacterial Growth Medium | Standardized medium for culturing and maintaining Pseudomonas strains. |

| Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) | Fungal Growth Medium | Standardized medium for culturing and maintaining fungal strains like Trichoderma. |

| Feather Meal / Guano | Organic Fertilizer | Slow-release nutrient source used to create realistic soil conditions and test microbial nutrient mobilization. |

| Stabilized Ammonium Sulfate | Mineral N Fertilizer (with nitrification inhibitor) | Used to maintain an ammonium-dominated root environment, which can enhance the effectiveness of certain PGPMs. |

| Zinquin ethyl ester | Zinquin ethyl ester, CAS:181530-09-6, MF:C21H22N2O5S, MW:414.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Nitroisoquinoline | 5-Nitroisoquinoline|High-Purity Research Chemical | High-quality 5-Nitroisoquinoline for research applications. Explore its use in synthesizing novel amides and metal complexes. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The body of evidence from meta-analyses and targeted studies confirms a clear quantitative performance advantage for microbial consortia over single-strain inoculants, with an approximate 60% greater improvement in plant growth and pollution remediation [3] [6]. However, this advantage is not universal; it is most pronounced under challenging environmental conditions such as abiotic stresses (drought, nutrient-poor soils) and in field settings where environmental variability is high [7] [8].

The design of effective consortia must account for synergistic partnerships between compatible strains and critical agronomic management factors, particularly the form of nitrogen fertilization. As the field of synthetic biology advances, enabling more rational design and construction of biological systems [9] [10], the development of precisely engineered microbial consortia represents a promising frontier for achieving more resilient and sustainable agricultural practices.

In microbial ecology, division of labor and metabolic cross-feeding represent fundamental synergistic mechanisms that enable microbial communities to achieve complex metabolic functions beyond the capabilities of individual strains. Division of labor occurs when distinct microbial subpopulations specialize in different metabolic tasks, effectively distributing the biochemical workload across community members [11]. Cross-feeding, the exchange of metabolites between different microbial species or strains, serves as the physical manifestation of this cooperation, where metabolic byproducts from one organism become nutrient sources for another [12]. These mechanisms collectively enhance community productivity, stability, and functional efficiency, making them crucial considerations in the comparative performance analysis of synthetic consortia versus individual strains.

Theoretical frameworks initially suggested limitations to these strategies. The competitive exclusion principle posited that the number of coexisting species could not exceed the number of limiting essential resources [11]. However, natural microbial systems consistently demonstrate stable coexistence of numerous species through violation of this principle via syntrophic interactions - obligately mutualistic metabolic relationships where partners together exploit substrates that neither could process alone [11] [12]. Understanding how these mechanisms function and their quantitative benefits provides critical insights for designing synthetic consortia with enhanced bioproduction, bioremediation, and therapeutic capabilities.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Consortia vs. Single Strains

Experimental data across multiple domains consistently demonstrates the performance advantages of microbial consortia implementing division of labor and cross-feeding strategies compared to single-strain implementations.

Table 1: Biomass and Biofertilization Performance Comparison

| System Type | Performance Metric | Improvement Over Control | Application Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-species inoculation | Plant growth | 29% increase | Biofertilization in live soil | [3] |

| Consortium inoculation | Plant growth | 48% increase | Biofertilization in live soil | [3] |

| Single-species inoculation | Pollution remediation | 48% increase | Bioremediation | [3] |

| Consortium inoculation | Pollution remediation | 80% increase | Bioremediation | [3] |

| Theoretical monoculture | Biomass productivity | Baseline | General metabolic function | [11] |

| Non-adapted binary consortia | Biomass productivity | Lower than monoculture | General metabolic function | [11] |

| Yield-optimized binary consortia | Biomass productivity | Higher than monoculture | General metabolic function | [11] |

Table 2: Therapeutic and Industrial Application Advantages

| System Type | Metabolic Burden | Functional Stability | Environmental Adaptability | Production Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single engineered strain | High | Moderate to Low | Limited | Constrained by cellular capacity |

| Synthetic microbial consortia (SyMCon) | Distributed across strains | Enhanced | Responds to multiple signals | Higher yield through specialization [13] |

The performance advantages evident in these tables stem from fundamental ecological and biochemical principles. Theoretical modeling reveals that simply splitting metabolic pathways between organisms without optimization actually decreases biomass production compared to a single "super microbe" containing all pathways [11]. The observed performance increases depend on critical adaptations in the specialized strains, particularly improved pathway efficiency (yield) rather than merely accelerated growth rates [11]. This efficiency gain occurs because specialized microbes can optimize a smaller set of pathways, reducing enzyme production costs and mitigating biochemical conflicts [11].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Microbial Synergy

Chemostat Modeling of Metabolic Specialization

Theoretical investigations of division of labor often employ chemostat models with standard Monod kinetics to compare metabolic strategies [11]. These models typically examine a metabolic chain where a substrate (A) converts to an intermediate (B), which then converts to a final product (C). The single-strain system performs both conversions (A→B→C), while the binary consortium splits this process between two specialized strains (A→B and B→C).

Key experimental parameters include:

- Growth kinetics (maximum growth rates and substrate affinities for each pathway)

- Metabolic yields (biomass produced per unit substrate)

- Inhibition constants (if intermediate B inhibits growth)

- Dilution rates (in continuous culture systems)

Model simulations systematically vary these parameters to identify conditions where division of labor provides productivity advantages. This approach revealed that yield improvements in specialized organisms provide the most plausible explanation for experimentally observed productivity increases in binary consortia [11].

Metabolomic Analysis of Cross-Feeding Interactions

Metabolomics provides empirical methodology for investigating cross-feeding mechanisms. One representative protocol examined cross-feeding between two Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) strains: P. megaterium PM and P. fluorescens NO4 [14].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomic Cross-Feeding Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | P. megaterium PM and P. fluorescens NO4 | Model organisms for studying cross-feeding interactions |

| Culture Medium | M9 minimal media | Defined, controlled environment without complex nutrient interference |

| Carbon Sources | Glucose (10.0 g/L) and Malic acid (2.0 g/L) | Primary and secondary carbon sources supporting metabolic activity |

| Centrifuge | 4,700 rpm capability | Separation of bacterial cells from conditioned media |

| Filtration System | 0.22 µm membrane filters | Sterilization of donor supernatant for cross-feeding experiments |

| Analytical Instrument | LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Metabolic profiling and identification of exchanged compounds |

Experimental workflow:

- Culture Preparation: Grow donor and receiver strains separately in M9 minimal media to OD600 = 1.0

- Conditioned Media Collection: Centrifuge donor cultures at 4,700 rpm for 15 minutes and filter-sterilize supernatants

- Cross-Feeding Setup: Inoculate receiver strains into donor-conditioned media at OD600 = 0.1

- Monitoring: Sample at intervals (0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 hours) for viability (OD600) and metabolite extraction

- Metabolite Analysis: Employ LC-MS-based metabolomics with multivariate statistical analysis

This methodology identified clear metabolic reprogramming in cross-fed organisms, including decreased primary metabolites (amino acids, sugars) alongside increased secondary metabolites (surfactins, salicylic acid, carboxylic acids) with roles in plant growth promotion and defense [14].

Diagram 1: Metabolomic cross-feeding experimental workflow.

Ecological and Evolutionary Perspectives

Fitness Impacts and Interaction Dynamics

Cross-feeding interactions manifest with varying fitness impacts on participating organisms, classified by ecological interaction types:

Diagram 2: Ecological interaction classifications in cross-feeding.

True syntrophy represents the most specialized form of mutualistic cross-feeding, classically defined as "obligately mutualistic metabolism" where partners collectively exploit substrates neither could metabolize alone [12]. The quintessential example is interspecies H2 transfer, where hydrogen producers and consumers establish obligate metabolic coupling [12]. Microbial specialization in these systems can become so extreme that participants undergo genome reduction, losing redundant metabolic capabilities and becoming irrevocably dependent on their partners [12].

The Community Stability Paradox

The prevalence of cooperative cross-feeding in stable, diverse ecosystems presents an ecological paradox. Classical ecological theory predicts that strongly cooperative interactions should create boom-and-bust cycles, reducing diversity and creating communities susceptible to invasion and collapse, especially through "cheater" exploitation [12]. However, natural microbial communities like the gut microbiome demonstrate remarkable stability despite extensive cross-feeding.

Explanations for this paradox center on two mechanisms:

- Blocking overgrowth of cooperative species through competitive interactions and host-mediated limitations (e.g., immune regulation)

- Weakening cooperative strength through spatial structure (increasing physical distance between partners) and functional redundancy (replacing single strong interactions with multiple weak ones) [12]

The context-dependence of these interactions further stabilizes communities; the same cross-feeding pair may shift from competition in high-nutrient conditions to obligate mutualism in nutrient-poor environments [12].

Engineering Synthetic Microbial Consortia

Design Principles and Construction Methods

Synthetic microbial consortia (SynComs) represent artificially constructed multi-strain communities designed for specific functions. Compared to single strains, mature SynComs exhibit superior stability, adaptability, efficiency, and metabolic flexibility [15]. The "design-build-test-learn" (DBTL) cycle has emerged as a standard framework for microbiome engineering [15].

Table 4: Synthetic Consortia Construction Methods

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Culture | Combining cultured strains based on known functions | High controllability, predictable interactions | Limited to culturable organisms | Well-characterized systems with available isolates |

| Core Microbiome Mining | Identifying key functional species from complex communities | Maintains ecological relevance | Requires advanced sequencing and analysis | Environmental applications with complex communities |

| Automated Design | High-throughput screening combined with computational modeling | Efficient, data-driven | High technical threshold, resource-intensive | Industrial bioprocessing with ample resources |

| Genetic Engineering | Modifying strains to create specific interactions | High precision, customizable | Regulatory concerns for environmental release | Therapeutic applications with controlled use |

Quorum Sensing-Engineered Therapeutic Consortia

Advanced synthetic microbial consortia (SyMCon) for therapeutic applications employ engineered quorum sensing (QS) systems for precise inter-strain communication [13]. These systems typically incorporate three essential modules:

Diagram 3: QS-engineered therapeutic consortium modules.

- Sensing modules detect pathological signals using engineered biosensors (e.g., butyrate-responsive PpchA-pchA system for colitis, nitrate-responsive NarX-NarL sensor) [13]

- Communication modules employ QS systems (AHLs, AI-2, AIPs) for density-dependent coordination

- Response modules produce and release therapeutic molecules (e.g., IL-22 for inflammation, cytotoxic compounds for tumors) [13]

This modular approach distributes metabolic burden across specialized strains, enabling complex functions impossible for single engineered bacteria, such as simultaneous sensing of multiple environmental signals and coordinated therapeutic delivery [13].

The comparative analysis of synthetic consortia versus individual strains demonstrates that division of labor and metabolic cross-feeding provide measurable performance advantages across agricultural, environmental, and therapeutic applications. The key synergistic mechanisms include distributed metabolic burden, increased pathway efficiency through specialization, and enhanced functional stability through ecological interactions.

Successful consortium design requires careful consideration of both ecological principles and engineering constraints. While theoretical models indicate that mere pathway splitting without optimization decreases performance, empirical evidence shows that yield-enhanced specialized strains in consortia can outperform generalist monocultures by 20-60% depending on the application [11] [3]. Future research directions should focus on orthogonal communication systems, complex genetic circuits, and modular consortium designs that can be adapted for personalized therapeutic applications [13].

These findings support the strategic implementation of synthetic microbial consortia in applications requiring complex metabolic functions, environmental resilience, and high productivity, provided that consortium design optimizes the synergistic mechanisms inherent in natural microbial communities.

Synthetic microbial consortia represent a paradigm shift in biotechnology, moving beyond single-strain engineering by designing communities of microorganisms that work together. This guide objectively compares the performance of these consortia against individual engineered strains, drawing on experimental data and lessons from natural gut and environmental microbiomes to inform their application in drug development and therapeutic design.

The table below summarizes the core comparative advantages of synthetic microbial consortia over single-strain inoculants, highlighting key performance differentiators.

Table 1: Performance Overview of Single Strains vs. Synthetic Consortia

| Performance Metric | Single-Strain Inoculants | Synthetic Microbial Consortia |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | High; all pathway components expressed in one cell, leading to resource competition and reduced productivity [16] | Low; division of labor distributes tasks, relieving individual metabolic burden [13] [16] |

| Functional Stability & Robustness | Prone to loss of function over time due to mutational escape; lower adaptability [17] | High; functional redundancy and distributed tasks enhance stability and adaptability to environmental fluctuations [15] [7] |

| Complex Function Capability | Limited by the host's genetic and metabolic capacity; complex circuit design is challenging [18] [16] | High; capable of complex, multi-step processes like full lignocellulose degradation or synergistic therapy [13] [17] |

| Reproducibility in Application | Variable; performance can be inconsistent across different environmental conditions [7] | More reproducible and controllable due to defined compositions and engineered stability [15] |

| Therapeutic Precision | Can be programmed for targeted functions (e.g., cytokine production) [19] | Superior; can be designed with multi-input sensing and coordinated, localized responses to complex disease signals [13] |

Quantitative Performance Data in Key Applications

Experimental data from foundational studies demonstrates the tangible advantages of a consortium-based approach in both bioproduction and therapeutics.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Key Consortium Applications

| Application Area | Experimental System | Performance Outcome (Consortium vs. Control) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioproduction | Co-culture of E. limosum (consumes CO) and engineered E. coli (consumes inhibitory acetate) [16] | More efficient CO consumption and biochemical production (e.g., itaconic acid) than E. limosum monoculture. | Mutualistic interaction in the consortium improved process efficiency and stability by mitigating metabolite inhibition [16]. |

| Bioproduction | Yeast co-culture specialists for glucose, arabinose, and xylose fermentation [17] | Higher sugar conversion rates and better long-term functional stability than a single generalist yeast strain. | Division of labor prevented the loss of pentose-fermenting function often seen in generalist strains, enhancing industrial suitability [17]. |

| Therapeutics | 37-strain Synthetic Fecal Microbiota Transplant (sFMT1) for C. difficile suppression [20] | Replicated the efficacy of a human fecal transplant in a gnotobiotic mouse model. | A single strain performing Stickland fermentation was identified as both necessary and sufficient for suppression, a discovery enabled by the tractable consortium model [20]. |

| Agriculture | Microbial Consortia Products (MCPs) vs. single strains in tomato production [7] | In challenging desert soil, MCPs improved phosphate acquisition, shoot biomass, and final fruit yield under low P supply. | Single strains performed similarly to MCPs in a balanced greenhouse setting, but MCPs showed superior performance under environmental stress [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Development

The construction and testing of synthetic consortia follow a rigorous, iterative cycle. The workflow below outlines the key phases, from design to validation.

Protocol Details

Design Phase

- Objective Definition: Clearly define the consortium's desired function, such as the production of a specific therapeutic molecule (e.g., butyrate) or the detection and suppression of a pathogen [21] [20].

- Strain Selection: Choose microbial chassis based on their native functions, genetic tractability, and compatibility. Common chassis include Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, Bacteroides species, and Lactococcus lactis for gut applications, or Pseudomonas putida and Rhodococcus for environmental processes [19] [17].

- Metabolic Modeling: Use Genome-Scale Metabolic models (GEMs) and computational tools like SteadyCom to simulate interactions, predict community assembly, and optimize the division of labor before experimental construction [21] [18].

Build Phase

- Genetic Engineering: Employ advanced tools like CRISPR-Cas systems to make precise genomic edits (knock-outs, insertions) in chosen chassis strains. This is used to eliminate competing pathways or integrate new biosynthetic modules [19].

- Program Communication: Engineer quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms using acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) or other signaling molecules to enable synchronized, density-dependent behavior and coordination between different strains in the consortium [13] [16].

Test Phase

- In Vitro Co-culture: Assemble engineered strains in a chemically defined medium under controlled environmental conditions (e.g., anaerobic chambers for gut microbes) [21].

- Functional Measurement: Quantify the consortium's output. This involves measuring target metabolite concentrations (e.g., via HPLC), tracking the degradation of pollutants, or assessing pathogen suppression in co-culture assays [21] [20].

- Stability Assessment: Monitor population dynamics over time using flow cytometry or sequencing to ensure stable coexistence and prevent the overgrowth of one strain [16].

Learn Phase

- Data Integration: Feed experimental data back into the computational models to refine parameter estimates and improve predictive accuracy [21].

- Iterative Refinement: Use model predictions to identify bottlenecks and inform the next cycle of design, for instance, by adjusting genetic parts or strain ratios [21] [18].

Engineered Signaling and Control Pathways

Stability and coordinated function in synthetic consortia are achieved by engineering specific ecological interactions. The diagram below illustrates three core control strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogues essential materials and tools for the construction and analysis of synthetic microbial consortia.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Consortium Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Model Chassis Strains | Engineered hosts with known genetics and culturing requirements. | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN), Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Lactococcus lactis, Pseudomonas putida [19] [17]. |

| Genetic Engineering Toolkits | For precise genomic modifications and circuit integration. | CRISPR-Cas12a systems for Bacteroides; CRISPR-Cas9 for E. coli; stable plasmid vectors with anaerobic promoters [19] [13]. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Engineered communication modules for coordinated behavior. | Acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) systems; Autoinducer-2 (AI-2); Orthogonal QS systems to prevent crosstalk [13] [16]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational modeling of metabolic interactions and predictions of community behavior. | SteadyCom (predicts steady-state abundances); BacArena (individual-based modeling) [18]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Supports reproducible co-culture by providing a fully known nutrient composition. | Essential for elucidating metabolic cross-feeding and quantifying nutrient consumption/production [21]. |

| Biosensor Components | Genetic parts that allow consortia to sense and respond to environmental signals. | Promoters responsive to inflammation markers (e.g., tetrathionate, nitrate), hypoxia, or specific metabolites [13]. |

| 16-Oxokahweol | 16-Oxokahweol | High Purity Reference Standard | 16-Oxokahweol, a coffee diterpene metabolite. For research into neurobiology & metabolism. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 4-Iodobutyl benzoate | 4-Iodobutyl benzoate, CAS:19097-44-0, MF:C11H13IO2, MW:304.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In microbial ecology, emergent properties refer to patterns or functions of a community that cannot be deduced as the simple sum of the properties of its constituent members [22]. These properties represent the synergistic potential that arises when multiple microbial strains interact within a consortium, leading to capabilities and functionalities that individual strains cannot achieve alone. The theoretical foundation of emergent properties rests on the principle that microbial communities function as higher-order units where microscopic interactions between individual strains give rise to macroscopic properties observable at the community level [22]. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in synthetic microbial communities (SynComs), where rational design principles are applied to construct consortia with predictable, enhanced functionalities for applications in biomedicine, agriculture, and environmental biotechnology [23].

Emergent properties typically arise when community members reach a critical threshold of community size and connectivity [22]. Examples in microbial systems include enhanced resilience to biotic and abiotic perturbations, stable co-existence of multiple species, niche expansion, spatial self-organization, and biochemical abilities that exceed the metabolic capabilities of individual strains [22]. The non-linear nature of these emergent properties makes mathematical modeling imperative for establishing the quantitative link between community structure and function [22]. Understanding and harnessing these properties is now recognized as a fundamental challenge in microbial ecology with significant implications for drug development, microbiome-based therapies, and bioproduction [23].

Comparative Performance: Consortia vs. Single-Strain Applications

Quantitative Meta-Analysis of Performance Advantages

A global meta-analysis of 51 live-soil studies systematically compared the impacts of single-species versus microbial consortium inoculation on biofertilization and bioremediation efficacy [3]. The results demonstrated clear and significant advantages for consortium-based approaches across both domains, with the diversity of inoculants and synergistic effects between commonly used inoculums such as Bacillus and Pseudomonas contributing to the enhanced effectiveness of consortium inoculation [3].

Table 1: Meta-Analysis of Single-Species vs. Consortium Inoculation Effects

| Performance Metric | Single-Species Inoculation | Consortium Inoculation | Comparison Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Increase | 29% improvement vs. non-inoculated control | 48% improvement vs. non-inoculated control | 65% relative improvement for consortia |

| Pollution Remediation | 48% improvement vs. non-inoculated control | 80% improvement vs. non-inoculated control | 67% relative improvement for consortia |

| Field Performance | Reduced efficacy compared to greenhouse results | Maintained significant advantage over single-strain | Superior environmental adaptability |

Despite a general reduction in efficacy in field settings compared to greenhouse conditions, consortium inoculation maintained a more significant overall advantage across various environmental conditions [3]. The analysis further recommended optimizing environmental conditions, including increasing original soil organic matter, available nitrogen and phosphorus content, and regulating soil pH to 6-7, to achieve better inoculation effects [3].

Agricultural Performance Under Differential Environmental Challenges

Direct comparative studies of single-strain inoculants versus microbial consortia products (MCPs) in tomato production systems have revealed context-dependent performance advantages [7]. Under protected greenhouse conditions in Timisoara, Romania, with composted cow manure, guano, hair-, and feather-meals as major fertilizers, both fungal and bacterial single-strain inoculants and microbial consortium products showed similar beneficial responses, significantly improving nursery performance, fruit setting, fruit size distribution, seasonal yield share, and cumulative yield (39-84% compared to control) over two growing periods [7].

However, under the more challenging environmental conditions of an open-field drip-fertigated tomato production system in the Negev desert, Israel—characterized by mineral fertilization on a high pH (7.9), low fertility sandy soil with limited phosphate availability—MCPs demonstrated superior performance [7]. This advantage was reflected in improved phosphate acquisition, stimulation of vegetative shoot biomass production, and increased final fruit yield under conditions of limited phosphorus supply [7].

Table 2: Agricultural Performance Under Different Environmental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Single-Strain Performance | Consortium Performance | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Greenhouse (Romania) | Significant improvement (39-84% yield increase) | Similar beneficial effects | No clear consortium advantage under optimized conditions |

| Open-Field Desert (Israel) | Limited efficacy under stress | Significant improvement in P acquisition and yield | Clear consortium advantage under challenging conditions |

| Rhizosphere Modulation | Minimal community changes | Selective changes in bacterial community structure | Increased Sphingobacteriia and Flavobacteria (salinity/drought indicators) |

| Phosphate Limitation | Reduced bacterial diversity | Restored rhizoplane diversity | Improved plant P status with MCP inoculation |

The superior performance of microbial consortia under challenging conditions was associated with selective changes in the rhizosphere bacterial community structure, particularly with respect to Sphingobacteriia and Flavobacteria, which have been reported as salinity indicators and drought stress protectants [7]. Notably, phosphate limitation reduced the diversity of bacterial populations at the root surface (rhizoplane), and this effect was reverted by MCP inoculation, reflecting the improved phosphorus status of the plants [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Laboratory Protocols for Consortium Assembly and Testing

The design and implementation of experiments comparing single-strain versus consortium approaches require standardized methodologies to ensure valid, reproducible results. For agricultural applications, typical experimental protocols involve several key phases. The pre-culture phase begins with sowing seeds in plastic pots containing a standardized nursery substrate mixture, typically based on composted cow manure, garden soil, peat, and sand in specific ratios (e.g., 45:30:15:10 v/v) [7]. At appropriate phenological growth stages (e.g., BBCH 51), nursery plants are transplanted to the main culture environment, which may involve greenhouse or open-field conditions with different soil types and fertilization regimes [7].

Microbial inoculants are typically applied through seed treatment, root dipping, or fertigation systems, depending on the experimental design and target application [7]. In controlled greenhouse studies, plants may be cultivated in containers filled with pre-fertilized clay peat substrate supplemented with organic fertilizers such as mixed hair/feather meal fertilizer at recommended dosages [7]. Supplementary foliar fertilization during the culture period is often divided into multiple cumulative application rates with specific nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium inputs [7].

For functional assessment, parameters such as plant growth characteristics, yield formation, fruit quality parameters, nutrient acquisition efficiency, and soil microbial community structure are monitored throughout the experiment duration [7]. Molecular analysis of rhizosphere communities through techniques such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing provides insights into the structural changes induced by different inoculation strategies [7].

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Mathematical modeling is indispensable for linking community composition and connectivity to emergent functions, bridging principles learned from simple laboratory systems to complex natural ecosystems [22]. Several modeling approaches have been developed to predict and analyze emergent properties in microbial consortia:

Lotka-Volterra Models: These models use nonlinear, coupled, first-order differential equations where the growth rate of a species population is described as a function of its intrinsic growth rate and the linear effects exerted by other populations [22]. While requiring relatively few parameters (intrinsic growth rates for each species and interaction coefficients for species pairs), these models typically assume static interactions and pair-wise relationships, potentially missing higher-order interactions [22].

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSSMs): These metabolism-centered models have intracellular reactions as main units and nutrient generation/consumption as the focus, providing detailed insights into metabolic interactions and resource partitioning within consortia [22] [23].

Consumer-Resource Models: These approaches explicitly represent the dynamics of resources that microbial species consume and produce, offering mechanistic insights into how resource competition and cross-feeding contribute to emergent community properties [22].

Individual-Based Models: These models simulate individual cells or organisms, allowing for the emergence of population-level patterns from individual behaviors and interactions, particularly useful for understanding spatial self-organization [22].

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) framework has emerged as a systematic approach for engineering synthetic microbial communities with predictable emergent properties [23]. This iterative engineering framework comprises four stages: Design (computational prediction of interaction networks), Build (assembly of defined microbial consortia), Test (functional validation under target conditions), and Learn (data-driven model refinement) [23].

Diagram 1: DBTL Framework for Consortium Design

Signaling Pathways and Interaction Networks

Microbial Interaction Typologies and Network Dynamics

Microbial interactions within consortia follow defined typologies that govern community dynamics and emergent properties. These interactions can be categorized as positive interactions (mutualism, commensalism), negative interactions (competition, antagonism, amensalism), and exploitative relationships (cheating behavior) [23]. The balance and spatial organization of these interaction types fundamentally determine the stability, functionality, and emergent properties of microbial consortia.

Positive interactions frequently emerge from metabolic specialization, where cross-feeding of metabolic byproducts enhances overall efficiency and resilience [23]. Engineered SynComs leveraging such positive interactions demonstrate superior performance, as evidenced by cross-feeding yeast consortia that increase bioproduction yields through evolved mutualism [23]. Negative interactions primarily manifest through competition for limited resources (nutrients, space) and chemical warfare mediated by antimicrobial compounds [23]. Interestingly, even in cooperative systems, competition can emerge upon community expansion, highlighting the dynamic nature of microbial interactions [23].

Cheating behavior represents a significant challenge in consortium design, where certain members exploit shared resources without contributing, potentially leading to the collapse of mutualistic partnerships [23]. Spatial organization has emerged as a powerful strategy for enhancing cooperation while suppressing cheating, as confined microenvironments alter quorum sensing dynamics and public goods distribution [23].

Diagram 2: Microbial Interaction Networks

Metabolic Pathways and Cross-Feeding Mechanisms

At the molecular level, emergent properties in microbial consortia are fundamentally governed by metabolic interactions and cross-feeding relationships. These interactions involve the exchange of metabolites, signaling molecules, and public goods that create interdependencies between consortium members. The division of labor principle, where metabolic pathways are distributed across different strains, enables consortia to perform complex functions that would be metabolically burdensome or impossible for individual strains [23].

Key metabolic interaction types include: complementary resource utilization, where different strains specialize in consuming different substrates; cross-feeding, where metabolic byproducts from one strain serve as substrates for another; and collective stress tolerance, where consortium members collaboratively mitigate environmental stresses through complementary protection mechanisms [23]. These metabolic interactions often lead to emergent metabolic capabilities, where the consortium can degrade complex substrates or synthesize valuable compounds more efficiently than any single member [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation of emergent properties in multi-strain systems requires specialized research reagents and materials designed to support the assembly, maintenance, and analysis of synthetic microbial communities. The following table details essential research tools and their specific functions in consortium research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Consortium Studies

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Media Formulations | Provide controlled nutritional environment for consortium assembly | In vitro studies of microbial interactions and cross-feeding dynamics |

| Soil Substrate Mixtures | Simulate natural environments for ecological studies | Greenhouse and field studies of plant-microbe interactions [7] |

| Organic Fertilizers (guano, feather meal) | Serve as nutrient sources while supporting microbial diversity | Agricultural studies of biofertilizer efficacy [7] |

| Molecular Barcoding Primers | Enable strain-level tracking and community composition analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomic analysis of consortium dynamics |

| Fluorescent Tagging Proteins | Visualize spatial organization and strain localization | Microscopy analysis of consortium structure and interactions |

| Quorum Sensing Reporters | Monitor cell-cell communication dynamics | Studies of signaling-mediated emergent behaviors |

| Metabolomic Standards | Quantify metabolic exchange and cross-feeding | Analysis of metabolic interactions within consortia |

| Antibiotic Selection Markers | Maintain consortium composition and prevent contamination | Controlled assembly of defined synthetic communities |

| Cryopreservation Media | Enable long-term storage of consortium libraries | Preservation of reference consortia for reproducible research |

| Microfluidic Device Systems | Create spatially structured environments for consortium studies | Analysis of population dynamics in confined geometries |

| Linalool oxide | Linalool oxide, CAS:5989-33-3, MF:C10H18O2, MW:170.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzalazine | Benzalazine (CAS 588-68-1) - High Purity Azine Reagent | High-purity Benzalazine from a trusted supplier. This compound is for professional research use only (RUO). Not for personal, household, or medicinal use. |

Advanced research in emergent properties increasingly relies on automated cultivation systems that enable high-throughput screening of consortium combinations, multi-omics integration platforms for analyzing relationships between community composition and function, and computational modeling tools for predicting consortium dynamics and stability [23]. The convergence of these experimental and computational tools is accelerating the transition from empirical consortium construction to predictive ecosystem engineering [23].

The theoretical foundations of emergent properties in multi-strain systems reveal a consistent pattern of functional advantages for microbial consortia over single-strain inoculants across diverse application domains. Quantitative meta-analyses demonstrate significant performance enhancements, with consortium inoculation improving plant growth by 48% compared to 29% for single-species inoculation, and pollution remediation by 80% compared to 48% for single-species approaches [3]. While these advantages are context-dependent—more pronounced under challenging environmental conditions—the overall evidence supports the superior resilience, functional capacity, and adaptability of properly designed microbial consortia [7].

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia with predictable emergent properties represents a paradigm shift in microbial biotechnology, moving from trial-and-error approaches to rational design principles grounded in ecological theory [23]. Key design principles include the strategic balancing of cooperative and competitive interactions, hierarchical species orchestration ensuring structural integrity through keystone species governance, evolution-guided artificial selection overcoming functional-stability trade-offs, and modular metabolic stratification for efficient resource partitioning [23]. As research in this field advances, the integration of computational modeling, high-throughput screening, and molecular characterization techniques will further enhance our ability to harness emergent properties for biomedical, agricultural, and industrial applications.

Engineering Microbial Alliances: Design Strategies and Therapeutic Applications

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving beyond the capabilities of individual engineered strains. These consortia leverage division of labor, where different sub-populations perform specialized tasks, leading to more robust and complex biological systems. This guide objectively compares the core enabling technologies—CRISPR-Cas9 systems and advanced DNA assembly toolkits—for constructing and optimizing such consortia, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their selection for specific consortium engineering applications.

The performance of synthetic consortia is highly dependent on the precision and efficiency of genetic modifications in individual strain members, as well as the ability to assemble complex genetic circuits that govern intercellular interactions. This review provides a direct performance comparison of modern CRISPR-based editing platforms and DNA assembly systems, focusing on their application in building multi-strain systems for therapeutic and bioproduction applications.

Performance Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies

CRISPR-Cas9 vs. Traditional Editing Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | TALENs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | Guide RNA (gRNA) | Protein-DNA binding (zinc finger domains) | Protein-DNA binding (TALE repeats) |

| Efficiency | High; capable of multiple simultaneous edits [24] [25] | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Specificity | Moderate to High; subject to off-target effects [24] [25] | High | High |

| Ease of Use | Simple gRNA design; accessible with basic molecular biology expertise [24] [25] | Requires extensive protein engineering [24] | Challenging design and implementation [25] |

| Cost | Low | High | High |

| Scalability | High; ideal for high-throughput experiments [24] | Limited | Limited |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs) | Low | Low |

| Therapeutic Applications | Clinical trials for sickle cell, beta thalassemia, hATTR [26] | HIV therapy [24] | Hemophilia therapy [24] |

CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized genetic engineering due to its simple guide RNA-based targeting mechanism, which eliminates the need for complex protein engineering required by ZFNs and TALENs [24] [25]. This accessibility has dramatically accelerated the development of synthetic consortia by enabling simultaneous editing of multiple genomic loci across different consortium members. For therapeutic applications, CRISPR-based therapies have advanced to clinical trials for multiple genetic disorders, including sickle cell disease, beta-thalassemia, and hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) [26].

While traditional methods like ZFNs and TALENs offer high specificity and have proven successful in clinical applications for HIV and hemophilia, their complexity and cost limit their practicality for large-scale consortium engineering projects requiring extensive genetic manipulation [24]. The multiplexing capability of CRISPR systems is particularly valuable for consortium engineering, where coordinated edits across multiple strains are often necessary to establish division of labor.

Advanced CRISPR Systems Beyond Native Cas9

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced CRISPR-Derived Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Editing Type | Efficiency | Key Applications in Consortium Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editing | Fusion of catalytically impaired Cas with deaminase enzymes | Single nucleotide conversion without DSBs | High (typically >50% in optimized systems) | Creating precise metabolic control switches |

| Prime Editing | Cas9-reverse transcriptase fusion with pegRNA | Targeted insertions, deletions, and all base-to-base conversions | Moderate to High (varies by cell type) | Installing pathway regulators without donor templates |

| CRISPRa/i | dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators/repressors | Gene expression modulation without DNA cleavage | High (up to 1000-fold induction reported) | Tunable control of metabolic fluxes in sub-populations |

| CAST Systems | CRISPR-associated transposases | Large DNA fragment insertion without DSBs | High in prokaryotes (>90% in E. coli) | Stable integration of biosynthetic pathways |

The evolution of CRISPR technology beyond simple cutting enzymes has created specialized tools for consortium engineering. Base editors enable precise single-nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks (DSBs), reducing unintended mutations and making them ideal for installing point mutations that fine-tune metabolic pathway regulation [24] [27]. Prime editors offer even greater versatility, capable of making all types of small edits without DSBs or donor templates, though efficiency can vary across different microbial hosts [28] [27].

For controlling gene expression in consortium members without permanent genetic changes, CRISPR activation and interference (CRISPRa/i) systems use catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional effectors to precisely tune expression levels of target genes [29]. This is particularly valuable for dynamically balancing metabolic fluxes across different sub-populations in a consortium.

For pathway engineering, CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems enable insertion of large DNA fragments (up to 30 kb) without DSBs, allowing stable integration of entire biosynthetic pathways into consortium members [27]. While currently most efficient in prokaryotic systems, ongoing development is improving their efficacy in eukaryotic hosts.

DNA Assembly Toolkits for Complex Construct Engineering

Modular DNA Assembly Systems

Advanced DNA assembly toolkits are essential for constructing the complex genetic circuits required to coordinate behavior in synthetic consortia. Modern toolkits have evolved from simple single-vector systems to modular platforms that support rapid assembly of multi-gene constructs.

The YaliCraft toolkit for Yarrowia lipolytica exemplifies this approach, featuring a modular architecture with 147 plasmids and 7 specialized modules that enable various genetic operations through Golden Gate assembly [30]. This system addresses critical bottlenecks in consortium engineering by enabling: (1) easy switching between marker-free and marker-based integration, (2) rapid redirection of integration cassettes to alternative genomic loci via homology arm exchange, and (3) simplified gRNA assembly through recombineering in E. coli [30].

Such modular systems are particularly valuable for engineering consortia because they enable rapid iteration of construct design and facilitate the standardization of genetic parts across multiple consortium members. The ability to quickly exchange regulatory elements and targeting sequences allows researchers to optimize inter-strain communication pathways and metabolic balancing without completely rebuilding constructs.

Advanced Integration Technologies

Table 3: Comparison of DNA Integration Technologies for Pathway Assembly

| Technology | Mechanism | Insert Size Capacity | Efficiency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | CRISPR-induced DSB with donor template | Moderate (<5 kb typically) | Low to Moderate (cell cycle dependent) | High precision |

| Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI) | NHEJ-mediated insertion | Large (≥10 kb) | Moderate | Works in non-dividing cells |

| Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE) | Site-specific recombinases | Large (≥10 kb) | High | Predictable, single-copy integration |

| CAST Systems | RNA-guided transposases | Very Large (up to 30 kb) | High in prokaryotes | DSB-free, highly specific |

| Gomisin L1 | Gomisin L1 - CAS 82425-43-2 - Lignan for Cancer Research | Gomisin L1 is a bioactive lignan from Schisandra berries for research use only (RUO). It induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer studies. Inhibits cell viability. | Bench Chemicals | |

| DL-Propargylglycine | DL-Propargylglycine, CAS:64165-64-6, MF:C5H7NO2, MW:113.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

For installing large genetic constructs into consortium members, several integration technologies offer different advantages. Traditional HDR works effectively in organisms with high homologous recombination efficiency but is limited by small insert size and cell-cycle dependence [27]. HITI leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway to enable larger insertions in non-dividing cells, but can result in unintended indels [27].

Recombinase-based systems like RMCE provide highly efficient, predictable integration of large DNA fragments and are particularly valuable when single-copy integration is required for consistent expression across consortium members [27]. The emerging CAST systems represent the most promising technology for large fragment integration, combining RNA-guided targeting with transposase-mediated insertion to enable DSB-free integration of very large constructs (up to 30 kb) [27].

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Engineering

Assessment of Editing Efficiency in Consortium Members

Accurately measuring editing efficiency is crucial for characterizing and optimizing synthetic consortia, as editing outcomes can vary significantly between different microbial species. Multiple methods are available with different tradeoffs:

T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay: This mismatch detection assay cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed by hybridization of edited and wild-type PCR products, producing distinguishable bands on agarose gels. While rapid and inexpensive, it provides only semi-quantitative results and lacks sensitivity compared to modern quantitative techniques [28].

Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) & Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE): These Sanger sequencing-based methods use sequence trace decomposition algorithms to quantify the frequencies of different editing outcomes. They offer more quantitative analysis than T7EI but depend heavily on PCR amplification and sequencing quality [28].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This method uses differentially labeled fluorescent probes to provide absolute quantification of editing efficiencies with high precision. It is particularly valuable for discriminating between different edit types (e.g., NHEJ vs. HDR) and determining the frequency of edited versus unedited cells in a population [28].

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Method Assessment of Editing Efficiency

- Sample Preparation: Harvest cells from each consortium member strain 72 hours post-transfection with editing constructs.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Use standardized extraction kits to obtain high-quality genomic DNA from all strains.

- Parallel Analysis:

- T7EI Assay: Amplify target region by PCR (30 cycles, 60°C annealing). Hybridize PCR products and digest with T7EI at 37°C for 30 minutes. Separate fragments on 1% agarose gel and quantify band intensities using densitometry [28].

- TIDE/ICE Analysis: Perform Sanger sequencing of target regions. Upload sequencing chromatograms (.ab1 files) to TIDE web tool or ICE analysis software. Set decomposition window to encompass the edited region (typically 100-200 bp around cut site) [28].

- ddPCR: Design FAM- and HEX-labeled probes for wild-type and edited sequences. Perform ddPCR reaction with 20,000 droplets per sample. Quantify editing efficiency as ratio of positive droplets for each fluorophore [28].

- Data Integration: Combine results from all methods to obtain comprehensive editing efficiency profile across consortium members.

Toolkit Assembly for Consortium Strain Engineering

The YaliCraft toolkit protocol demonstrates a systematic approach to engineering consortium members:

Experimental Protocol: Modular Strain Engineering

- Toolkit Access: Obtain the basic set of 147 plasmids and 7 module types from repository sources.

- Modular Assembly:

- Module 1 (Promoter/ORF Assembly): Combine selected promoters and open reading frames via Golden Gate assembly using BsaI restriction enzyme.

- Module 2 (Terminator Integration): Add appropriate terminators to transcription units.

- Module 3 (Multigene Assembly): Combine multiple transcription units using Golden Gate assembly with Esp3I.

- Module 4 (Homology Arm Exchange): Redirect assembled constructs to alternative genomic loci by exchanging homology arms via Golden Gate reaction [30].

- gRNA Assembly: For CRISPR-based editing, assemble guide sequences via recombineering between Cas9-helper plasmids and single oligonucleotides in E. coli [30].

- Transformation: Co-transform assembled editing constructs and gRNA plasmids into target consortium members.

- Validation: Confirm edits via diagnostic PCR and sequencing across integration junctions.

Modular Engineering Workflow for Synthetic Consortia

Reagent Toolkit for Consortium Engineering

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Consortium Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Consortium Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, FnCas12a, CasMINI | Targeted DNA cleavage for genetic editing of consortium members |

| Editing Enhancers | HDR enhancers, NHEJ inhibitors | Improve specific editing outcomes in different strain backgrounds |

| Assembly Systems | Golden Gate Mix, Gibson Assembly Mix | Modular construction of complex genetic circuits |

| Delivery Tools | Electroporation kits, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Efficient introduction of editing components into diverse species |

| Efficiency Assays | T7EI assay kit, ddPCR supermixes | Quantify editing success across consortium members |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, Fluorescent proteins | Track and maintain engineered strains in consortium |

| Modular Vectors | YaliCraft toolkit, Golden Gate compatible vectors | Standardized parts for rapid strain construction |

| Sarasinoside B1 | Sarasinoside B1, MF:C61H98N2O25, MW:1259.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Heptyl-4-quinolone | 2-Heptyl-4-quinolone, CAS:40522-46-1, MF:C16H21NO, MW:243.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that advanced CRISPR-Cas9 systems and modular DNA assembly toolkits provide unprecedented capability for engineering synthetic microbial consortia. CRISPR technologies offer superior flexibility and multiplexing capacity compared to traditional editing platforms, while modern DNA assembly systems enable rapid construction of complex genetic circuits that distribute metabolic pathways across multiple strains.

For researchers engineering synthetic consortia, the selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific requirements of the application. For consortia requiring extensive genome editing across multiple strains, CRISPR-Cas9 systems with high-fidelity variants provide the necessary precision and efficiency. For consortia where metabolic balancing is critical, CRISPRa/i systems offer dynamic control without permanent genetic changes. Modular DNA assembly toolkits are essential for rapidly iterating on consortium design and standardizing genetic parts across different strain backgrounds.

The integration of these technologies—combining the precision of CRISPR editing with the flexibility of modular DNA assembly—enables the creation of sophisticated synthetic consortia with specialized divisions of labor. As these toolkits continue to evolve, particularly with the integration of AI-designed editors [31] and improved large-fragment integration systems [27], they will unlock even greater potential for constructing complex microbial communities for therapeutic, bioproduction, and environmental applications.

Modular design frameworks represent a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, enabling the construction of complex biological systems from standardized, interchangeable parts. This approach allows researchers to decompose intricate biological functions into discrete modules responsible for sensing environmental cues, processing information, and executing programmed responses. Within synthetic microbial communities (SynComs), this modularity becomes particularly powerful, allowing scientists to engineer consortia where specialized functions are distributed across different microbial strains rather than attempting to engineer all capabilities into a single organism [23]. The comparative performance between these multi-strain synthetic consortia and individual engineered strains represents a critical frontier in biological engineering, with significant implications for drug development, biomedical applications, and industrial biotechnology.

The fundamental architecture of these systems typically comprises three core module types: sensing modules that detect specific environmental signals or biomarkers, communication modules that enable information exchange between cellular units, and response modules that execute defined biological functions. This architectural separation allows for greater flexibility in system design and optimization, as modules can be independently improved and recombined to create systems with novel capabilities [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the performance characteristics of these modular frameworks is essential for selecting appropriate design strategies for specific applications, whether developing novel therapeutics, biosensors, or bioproduction platforms.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Synthetic Consortia vs. Individual Strains

The choice between implementing a biological system using a synthetic consortium of specialized strains or a single extensively engineered strain involves significant trade-offs across multiple performance dimensions. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics based on current research findings:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthetic Consortia vs. Individual Engineered Strains

| Performance Metric | Synthetic Consortia | Individual Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Complexity | High (Distributed functions across specialists) [23] | Limited (Burden of all functions on single strain) [23] |

| Metabolic Burden | Distributed (Lower per-strain burden) [23] | Cumulative (High burden on single chassis) [23] |

| Stability & Robustness | Context-dependent (Can leverage ecological principles) [23] | Often challenging (Prone to evolutionary drift) [23] |

| Engineering Tractability | More complex (Requires multi-strain coordination) [23] | Simplified (Single strain optimization) [23] |

| Productivity/Yield | Potentially higher (via division of labor) [23] | Often limited by cellular capacity [23] |

| Predictability | Lower (Emergent interactions) [23] | Higher (Reduced variables) [23] |

Synthetic consortia excel in applications requiring complex, distributed functions that would overwhelm the metabolic capacity of a single strain. The division of labor principle allows different community members to specialize in specific tasks, potentially increasing overall system productivity and efficiency [23]. For instance, in bioproduction applications, consortia have demonstrated the ability to achieve higher yields by distributing metabolic pathways across multiple specialists, thereby reducing the burden on any single strain [23]. This approach has shown particular promise in complex biosynthesis pathways where intermediate metabolites can be toxic or place excessive demand on cellular resources.