Trait-Based vs. Directed Evolution: A Strategic Guide for Optimizing Biological Communities and Bioprocesses

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between two powerful paradigms for biological optimization: trait-based ecology and directed evolution.

Trait-Based vs. Directed Evolution: A Strategic Guide for Optimizing Biological Communities and Bioprocesses

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between two powerful paradigms for biological optimization: trait-based ecology and directed evolution. We explore the foundational principles of both approaches, from the analysis of functional traits that govern community performance to the laboratory-driven iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection. The scope covers modern methodologies, including CRISPR-based diversification and high-throughput screening, alongside practical strategies for troubleshooting yield variation and process control. By synthesizing insights from theoretical ecology and applied biotechnology, this guide offers a validated framework for selecting the optimal strategy to engineer microbes, cellular communities, and biocatalysts for enhanced robustness, yield, and novel function in biomedical applications.

Core Principles: From Natural Trait Diversity to Laboratory-Driven Evolution

In the pursuit of optimizing biological systems for research and therapeutic applications, two powerful methodologies have emerged: trait-based evolution and directed evolution. While both approaches harness evolutionary principles, they differ fundamentally in their philosophy, implementation, and application. Trait-based evolution is an analytical framework rooted in quantitative genetics that investigates how phenotypic traits evolve in natural populations or communities in response to selective pressures. In contrast, directed evolution is an engineering methodology that mimics natural selection in laboratory settings to optimize biomolecules for specific human-defined functions. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these paradigms, offering researchers a clear framework for selecting appropriate strategies for biological optimization challenges.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Trait-Based Evolution

Trait-based evolution approaches investigate how heritable phenotypic characteristics change in populations over time in response to environmental selective pressures [1]. This framework is grounded in quantitative genetics, which analyzes the evolution of continuous traits influenced by multiple genes and environmental factors. The core mathematical framework is described by the Lande equation: Δz̄ = G∇ȳ, where Δz̄ represents the change in mean phenotype, G is the genetic variance-covariance matrix, and ∇ȳ is the selection gradient [1]. This equation highlights that evolutionary response depends not only on the strength of selection but also on the available genetic variation and its structure.

These approaches typically study evolution in natural populations or controlled experimental settings where selective pressures are observed or manipulated rather than designed. Research focuses on understanding fundamental evolutionary processes, including how traits evolve in response to environmental changes, species interactions, and community dynamics [1] [2]. A key consideration is the evolution of trait variance itself—as species diversity increases in communities, competition often drives the evolution of narrower trait breadths in individual species, which can surprisingly reduce overall functional diversity despite increased species richness [2].

Directed Evolution

Directed evolution is a protein engineering methodology that mimics natural evolution in laboratory settings to optimize biomolecules for specific applications [3] [4]. This approach involves iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection to rapidly isolate improved variants without requiring detailed mechanistic understanding of the sequence-function relationship [5] [6].

The fundamental process consists of creating genetic diversity in a target gene through random or targeted mutagenesis, expressing these variants to create a library, screening or selecting for desired properties, and using improved variants as templates for subsequent evolution cycles [4]. Unlike natural evolution, directed evolution operates on human-defined objectives and typically occurs over much shorter timescales—weeks or months rather than centuries [3]. This methodology effectively navigates complex fitness landscapes by exploring sequence spaces that would be difficult to predict rationally, making it particularly valuable for engineering proteins with novel functions or improved stability [5] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Trait-Based and Directed Evolution Approaches

| Characteristic | Trait-Based Evolution | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Understand natural evolutionary processes | Engineer biomolecules with desired properties |

| Theoretical Basis | Quantitative genetics, population genetics | Molecular evolution, protein engineering |

| Typical Context | Natural populations, ecological communities | Laboratory experiments, industrial applications |

| Timescale | Generational (medium to long-term) | Rapid cycles (days to weeks) |

| Genetic Diversity Source | Standing variation, new mutations | Artificially generated mutations |

| Key Outcome | Understanding of evolutionary patterns | Optimized biomolecules for specific applications |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Trait-Based Evolution Workflows

Trait-based evolution research employs both observational and experimental approaches to investigate evolutionary processes. Long-term observational studies monitor natural populations over extended periods, such as the landmark research on Darwin's finches that has documented evolutionary changes in beak size and shape in response to climatic variations over four decades [7]. These studies incorporate natural environmental complexity, population demographics, and species interactions without experimental manipulation.

Experimental field approaches manipulate selective pressures in natural settings to establish causal relationships between environmental factors and evolutionary outcomes. Examples include long-term studies of guppies in Trinidadian streams, where researchers introduced predators to different populations and observed subsequent evolutionary changes in life history traits [7]. Laboratory selection experiments provide greater environmental control, enabling researchers to examine evolutionary dynamics across thousands of generations while maintaining replicate populations. The Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) with Escherichia coli, ongoing for over 75,000 generations, has revealed fundamental principles about adaptive evolution, historical contingency, and the dynamics of trait evolution [7].

Directed Evolution Workflows

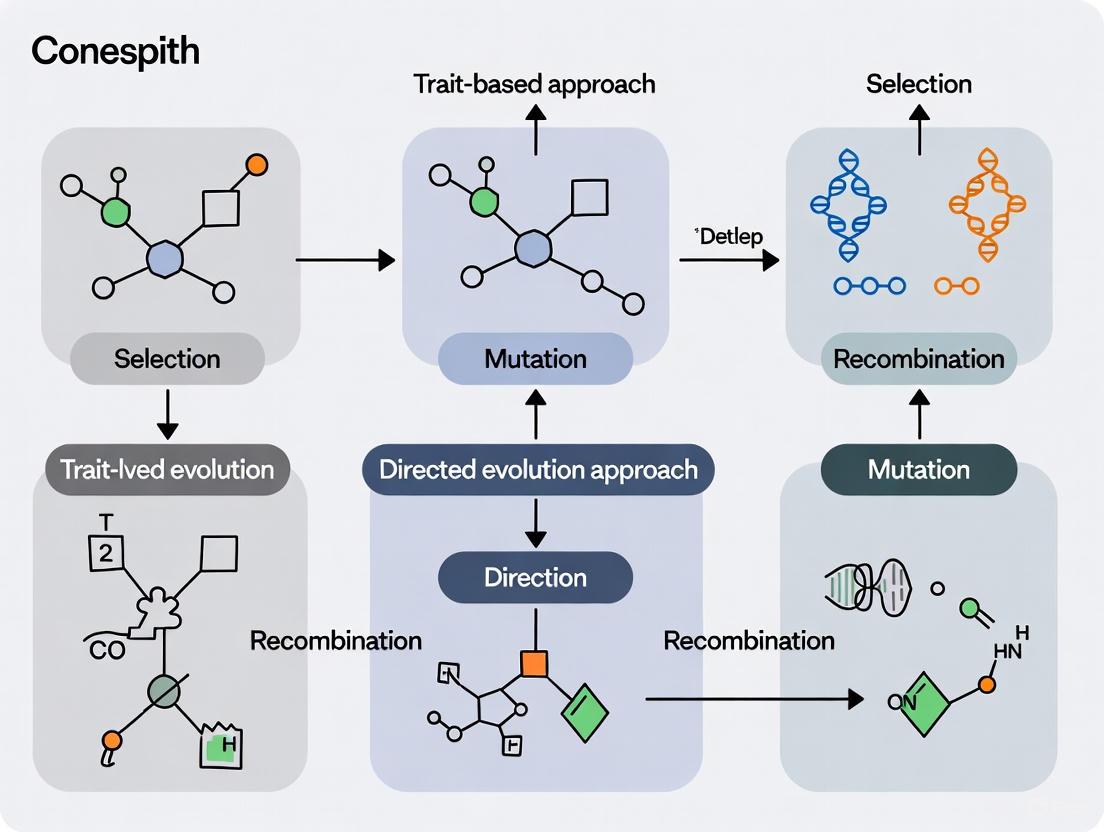

Directed evolution employs systematic laboratory protocols to engineer biomolecules through iterative diversification and selection. The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized directed evolution pipeline:

Library Generation Methods create genetic diversity through various mutagenesis strategies. Error-prone PCR introduces random point mutations throughout the gene sequence using reaction conditions that reduce polymerase fidelity [3] [4]. DNA shuffling recombines fragments from homologous genes to create chimeric proteins, mimicking natural recombination [4]. Site-saturation mutagenesis targets specific residues to explore all possible amino acid substitutions at chosen positions [3].

Selection and Screening Strategies enable identification of improved variants. Display techniques (phage, yeast, or ribosome display) physically link genotype to phenotype, allowing high-throughput screening of binding affinity or other properties [3]. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) enables ultra-high-throughput screening of cellular properties when the desired function can be linked to fluorescence [3] [5]. Microtiter plate assays facilitate medium-throughput screening of enzymatic activity using colorimetric or fluorimetric substrates [3].

Recent methodological advances focus on optimizing selection conditions to maximize efficiency. Approaches include Design of Experiments (DoE) to systematically evaluate multiple selection parameters and deep sequencing of selection outputs to identify significantly enriched mutants at appropriate coverage levels [5].

Table 2: Key Methodological Techniques in Directed Evolution

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Generation | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, Site-saturation mutagenesis, RAISE, TRINS | Creating genetic diversity in target genes | Varies by technique |

| Selection/Screening | Phage display, FACS, Microplate assays, QUEST, Cofactor regeneration coupling | Identifying variants with desired properties | 10^3 - 10^13 variants |

| Analysis | Next-generation sequencing, Functional characterization, Kinetic analysis | Validating improved variants and understanding mutations | Dependent on variant number |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Trait-Based Evolution Applications

Trait-based approaches provide critical insights for evolutionary biology, conservation, and understanding disease dynamics. In evolutionary rescue research, quantitative genetic models investigate whether populations can adapt rapidly enough to avoid extinction in changing environments, with implications for conservation biology amid climate change [1]. Cancer evolution studies apply evolutionary models to understand how tumor cell populations evolve in response to treatment, investigating how birth-death rate tradeoffs and cellular turnover influence evolutionary trajectories and therapy resistance [8].

Community ecology studies examine how trait evolution shapes species interactions and ecosystem functioning, revealing that increased species diversity does not necessarily increase functional diversity due to competitive constraints on trait variances [2]. Long-term evolutionary studies connect microevolutionary processes to macroevolutionary patterns, addressing fundamental questions about speciation, evolutionary innovations, and the emergence of complex traits [7].

Directed Evolution Applications

Directed evolution has revolutionized protein engineering for therapeutic and industrial applications. Enzyme engineering creates optimized biocatalysts with enhanced stability, activity, or novel substrate specificity for industrial processes and synthetic biology [3] [4]. Therapeutic protein engineering generates improved antibodies, hormones, and other biologics with enhanced potency, stability, or reduced immunogenicity [3].

Xenobiotic nucleic acid (XNA) polymerase engineering develops specialized enzymes capable of synthesizing and reverse-transcribing artificial genetic polymers with applications in therapeutics and biotechnology [5]. Transcription factor engineering rewires regulatory proteins to respond to novel inducters or regulate new DNA sequences, expanding the synthetic biology toolbox for genetic circuit construction [6]. Metabolic pathway engineering optimizes multi-enzyme pathways for production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and valuable chemicals through iterative optimization of pathway components [6] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolution Approaches

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Systems | Error-prone PCR kits, Chemical mutagens, Transposon-based mutagenesis systems | Introducing genetic diversity for directed evolution or experimental evolution studies |

| Display Technologies | Phage display systems, Yeast surface display, Ribosome display | High-throughput screening of protein-ligand interactions |

| Selection Tools | FACS systems, Microplate readers, Selective growth media | Identifying variants with desired properties from libraries |

| Analysis Reagents | Next-generation sequencing kits, Antibodies for detection, Enzyme substrates | Characterizing evolved variants and their properties |

| Specialized Polymerases | XNA polymerases, Error-prone polymerases, High-fidelity PCR enzymes | Enzymatic tools for library construction and specialized applications |

| (E)-Hex-3-en-1-ol-d2 | (E)-Hex-3-en-1-ol-d2, MF:C6H12O, MW:102.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-Sabutoclax | (S)-Sabutoclax, MF:C42H42N2O8S, MW:734.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Implementation

Methodological Synergies

While trait-based and directed evolution approaches differ in implementation, they offer complementary insights. Trait-based models can inform directed evolution strategies by predicting how traits might evolve under specific selective pressures [1] [2]. Conversely, directed evolution experiments provide empirical tests of evolutionary hypotheses generated by trait-based theories [4]. This synergy is particularly valuable for understanding complex evolutionary phenomena such as epistasis, historical contingency, and the emergence of novel functions.

Selection Guidelines

Researchers should consider several factors when choosing between these approaches:

Opt for trait-based evolution when:

- Studying natural evolutionary processes in ecological or population contexts

- Investigating evolutionary responses to environmental changes

- Understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits

- Modeling long-term evolutionary dynamics

Choose directed evolution when:

- Engineering biomolecules with specific, human-defined properties

- Optimizing proteins, pathways, or genetic circuits for industrial or therapeutic applications

- Exploring sequence-function relationships without detailed structural knowledge

- Generating novel biocatalysts not found in nature

Consider hybrid approaches when:

- Engineering complex traits influenced by multiple genes

- Developing evolutionary-informed biomolecule engineering strategies

- Testing evolutionary hypotheses through synthetic biology approaches

Trait-based and directed evolution represent distinct yet complementary paradigms for investigating and harnessing evolutionary processes. Trait-based approaches provide the theoretical foundation and analytical tools for understanding how traits evolve in natural systems, while directed evolution offers powerful engineering methodologies for optimizing biomolecules to address human needs. As both fields advance, integrating their insights and methodologies promises to accelerate progress in fundamental evolutionary biology, drug development, and biotechnology. Researchers can leverage the comparative frameworks presented here to select appropriate strategies for their specific biological optimization challenges.

The Theoretical Basis of Trait-Based Ecology and Community Assembly

The quest to understand and engineer biological communities has coalesced around two distinct philosophical and methodological approaches: trait-based ecology and directed evolution. Trait-based ecology represents a rational, design-forward framework where communities are constructed or analyzed based on functional characteristics of their constituent organisms [9] [10]. In contrast, directed evolution embraces a selection-based paradigm, applying iterative cycles of diversification and artificial selection to steer microbial consortia toward desired functional outcomes without requiring detailed knowledge of underlying mechanisms [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, examining their theoretical foundations, methodological implementations, and performance across research applications, with particular relevance for scientific and drug development professionals seeking to optimize microbial communities for therapeutic or industrial applications.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Core Principles of Trait-Based Ecology

Trait-based ecology operates on the fundamental premise that measurable organismal characteristics (traits) directly influence ecological performance and ecosystem functioning [12] [10]. This approach defines functional traits as morpho-physio-phenological characteristics that directly or indirectly link to fitness, growth, reproduction, and survival [13] [10]. The theoretical framework posits that community assembly is governed by environmental filtering—where abiotic conditions select for species possessing traits suitable for that environment—and biotic interactions, including competition, facilitation, and niche differentiation [14] [13].

A key theoretical advancement in trait-based ecology is the recognition that the relationship between species diversity and functional diversity is not necessarily positive. Research on Galápagos land snails demonstrated that in species-rich communities, competition can drive trait narrowing as species evolve narrower trait breadths to avoid competition, potentially reducing overall functional diversity [2]. This challenges the conventional assumption that increasing species diversity automatically enhances ecosystem functionality.

Trait-based approaches further theorize that environmental gradients filter species according to their traits, leading to predictable community assembly patterns. Studies across subtropical karst forests reveal consistent trait-mediated patterns where deciduous forests in drier, fertile soils exhibit resource acquisition traits (e.g., high specific leaf area), while evergreen forests in moist, infertile conditions display resource conservation traits (e.g., high leaf dry matter content) [14].

Core Principles of Directed Evolution

Directed evolution of microbial communities (DEMC) applies artificial selection principles to steer community-level functions through iterative diversification and selection cycles [11]. Unlike trait-based approaches that require deep understanding of functional mechanisms, DEMC operates agnostically to underlying interactions, instead harnessing selective pressures to enrich communities with desired functionalities [11].

The theoretical foundation of DEMC rests on several key principles: (1) microbial communities can be treated as selectable units, (2) community-level functions respond to selective pressures through compositional and functional shifts, and (3) iterative selection stabilizes desirable functional attributes. This approach leverages natural evolutionary processes—mutation, horizontal gene transfer, and selection—but directs them toward specific functional goals [11] [15].

Research in fermented food systems demonstrates that DEMC can enhance functional stability and performance without genetic engineering. For instance, microbial consortia subjected to acid stress develop improved acid resistance and metabolic performance under extreme pH conditions, illustrating how ecological adaptation through directed evolution produces robust functional outcomes [11].

Comparative Theoretical Framework

Table 1: Theoretical Comparison Between Trait-Based and Directed Evolution Approaches

| Theoretical Aspect | Trait-Based Ecology | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Environmental filtering and niche-based assembly | Artificial selection and evolutionary steering |

| Knowledge Requirement | Requires prior trait-function knowledge | Agnostic to mechanistic understanding |

| Timescale | Primarily ecological (contemporary) | Eco-evolutionary (multiple generations) |

| Unit of Selection | Individual traits/species | Whole community as selectable unit |

| Predictability | High when trait-function relationships known | Emergent through selection history |

| Stability Mechanisms | Niche differentiation and complementarity | Selected functional redundancy |

Methodological Implementation

Trait-Based Experimental Workflows

Trait-based methodologies follow rational design principles beginning with trait characterization and culminating in community assembly or analysis. The experimental workflow typically involves: (1) identifying relevant functional traits for target ecosystem functions, (2) measuring trait values across candidate species, (3) constructing communities based on trait compatibility and complementarity, and (4) validating functional outcomes [9] [16].

Advanced trait-based approaches incorporate phylogenetic inference to predict trait values when direct measurements are unavailable. Research on infant gut microbiome development employed a phylogeny-based method using 16S rRNA data and curated trait databases to infer traits like oxygen tolerance, sporulation ability, and 16S rRNA gene copy number across microbial taxa [13]. This approach enables trait-based analysis even when comprehensive trait measurements are lacking.

Table 2: Key Methodological Components in Trait-Based Ecology

| Methodological Component | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Community-Weighted Means (CWM) | Mean trait values weighted by species abundance | Quantifying dominant traits in karst forests [14] |

| Trait-Based Null Models | Statistical tests comparing observed trait distributions to random expectations | Identifying environmental filtering in plant communities [14] |

| Phylogenetic Trait Imputation | Using evolutionary relationships to infer unknown traits | Predicting microbial traits in infant gut development [13] |

| Functional Diversity Metrics | Quantifying the volume of trait space occupied by a community | Relating species diversity to functional diversity [2] |

Directed Evolution Methodologies

Directed evolution implements iterative selection cycles consisting of four key phases: (1) initial community construction, (2) application of selective pressure, (3) functional screening, and (4) propagation of superior communities [11] [15]. This design-build-test-learn cycle continues until communities stably maintain target functions.

In fermented food applications, DEMC typically begins with diverse starter communities from spontaneous fermentation, backslopping, or defined starters [11]. Selective pressures are then applied based on target functionalities—temperature stress for thermostability, acid stress for pH tolerance, or substrate limitations for metabolic efficiency. Functional screening identifies communities exhibiting enhanced performance, which are then propagated for subsequent selection cycles.

Recent technological innovations have enhanced DEMC capabilities. The PROTEUS platform uses chimeric virus-like vesicles to enable directed evolution in mammalian cells, addressing previous limitations in mammalian directed evolution systems [17]. This platform demonstrates how viral vectors can maintain system integrity across extended evolution campaigns while generating sufficient diversity for functional optimization.

Experimental Protocols for Community Optimization

Protocol 1: Trait-Based Community Assembly

- Initial Characterization: Quantify key functional traits across candidate species pool (e.g., specific leaf area, wood density for plants; oxygen tolerance, substrate utilization for microbes) [14] [13]

- Trait-Function Modeling: Establish statistical relationships between trait values and target functions using regression models or machine learning

- Community Design: Select species combinations that optimize trait complementarity based on functional objectives

- Validation: Assemble synthetic communities and measure functional outcomes versus predictions

- Refinement: Adjust trait-function models based on empirical results

Protocol 2: Directed Evolution of Microbial Communities

- Community Initiation: Construct initial diverse community from environmental samples, culture collections, or defined isolates [11]

- Diversification Phase: Allow natural mutation, horizontal gene transfer, or introduce random mutagenesis to generate variation

- Selection Pressure: Apply targeted stressor relevant to desired function (e.g., high temperature, acidic pH, antibiotic exposure)

- Screening and Propagation: Identify high-performing communities through functional assays; transfer superior communities to fresh medium

- Iteration: Conduct multiple cycles (typically 5-20) of diversification and selection

- Stabilization: Monitor functional stability across transfers without selection pressure

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Functional Optimization Efficiency

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Trait-Based versus Directed Evolution Approaches

| Performance Metric | Trait-Based Ecology | Directed Evolution | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Optimization | Weeks to months | Months to multiple generations | DEMC requires 5-20 cycles for fermented foods [11] |

| Functional Precision | High for known traits | Emergent, potentially superior for complex functions | Trait-based approaches enable precise division of labor [9] |

| Stability Outcomes | Variable, requires careful design | Often high through selected adaptations | DEMC communities maintain function under stress [11] |

| Novel Function Discovery | Limited to designed combinations | Can yield unexpected solutions | DEMC produces novel regulatory tools [17] |

| Knowledge Dependency | High prior knowledge required | Minimal prior knowledge needed | Trait-based relies on established trait-function relationships [10] |

| Technical Barriers | Trait measurement, modeling | High-throughput screening | DEMC benefits from automated screening [11] |

Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

Trait-based approaches have demonstrated particular success in environmental biotechnology where trait-function relationships are well-characterized. Synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) designed using trait-based principles show enhanced performance in pollutant degradation, where complementary metabolic traits are strategically combined [16]. Similarly, agricultural applications employ trait-based design to assemble plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria consortia with balanced competitive and cooperative interactions [16].

Directed evolution excels in optimizing complex, multifunctional outcomes where mechanistic understanding is limited. In fermented food production, DEMC has improved both sensory qualities and production efficiency simultaneously [11]. Medical applications include evolving microbial communities for gut microbiome therapeutics, where DEMC can steer communities toward stable, beneficial configurations without requiring complete understanding of underlying microbial interactions.

Emerging platforms like PROTEUS enable directed evolution of protein functions within mammalian cells, generating tools with mammalian-specific adaptations [17]. This technology has evolved tetracycline-controlled transactivators with altered doxycycline responsiveness, creating more sensitive genetic regulation tools for biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Community Optimization Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PROTEUS Platform | Mammalian directed evolution using virus-like vesicles | Protein evolution in mammalian cellular environment [17] |

| Error-Prone PCR | In vitro random mutagenesis | Generating diverse gene variants for directed evolution [15] |

| Multi-Omics Analysis | Comprehensive community characterization | Tracking compositional and functional changes in both approaches [16] [11] |

| Trait Databases | Curated functional trait data | Informing trait-based design across taxa [13] [10] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Targeted genome editing | Creating specific variants in trait-based design [15] |

| Automated Cultivation Systems | High-throughput community propagation | Scaling directed evolution experiments [11] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Predicting metabolic interactions | Informing trait-based community design [16] |

Trait-based ecology and directed evolution represent complementary rather than competing paradigms for community optimization. Trait-based approaches offer precision and predictability when mechanistic understanding is sufficient, while directed evolution provides powerful functionality discovery when systems are too complex for rational design. The most effective community engineering strategies will likely integrate both approaches—using trait-based principles to design initial communities and guide selective pressures, while employing directed evolution to refine and stabilize functional outcomes. This synergistic framework promises to accelerate development of microbial consortia for therapeutic applications, bioproduction, and environmental restoration, ultimately enhancing our ability to harness biological communities for human needs.

Directed evolution stands as one of the most powerful tools in protein engineering, mimicking the principles of natural selection to steer biological molecules toward user-defined goals. This method has transformed basic biological research and the development of therapeutics, enabling engineers to create proteins with enhanced stability, novel catalytic activities, and specific binding affinities without requiring prior structural knowledge. This guide traces the pivotal milestones in the history of directed evolution, objectively compares the performance of its key methodologies, and situates these advances within the broader thesis of trait-based versus directed evolution approaches for community optimization research. For the researcher, understanding this evolution is critical for selecting the optimal strategy for a given protein engineering challenge.

Historical Timeline: Key Experiments and Methodologies

The following table chronicles the major developments in directed evolution, from foundational concepts to contemporary, computationally-enhanced practices.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Directed Evolution

| Year(s) | Milestone / Experiment | Key Methodology | Impact & Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Spiegelman's Monster [18] [19] | In vitro evolution of a self-replicating RNA molecule using Qβ replicase, selecting for fastest-replicating variants. | Proof-of-concept: Demonstrated that molecules could be evolved artificially under selective pressure, resulting in a minimal, highly efficient 218-nucleotide RNA [19]. |

| 1980s | Development of Phage Display [18] [4] | Selection: A library of peptide variants is displayed on the surface of bacteriophages; binding to a target antigen enables isolation of high-affinity binders. | Enabled affinity maturation: Revolutionized antibody and peptide engineering. A direct lineage led to modern therapeutic antibodies [18]. |

| 1990s | Modern Directed Evolution of Enzymes [18] [4] | Random Mutagenesis & Screening: Iterative rounds of error-prone PCR and high-throughput screening for improved traits (e.g., stability, activity). | Established the modern paradigm: A seminal study evolved subtilisin E, achieving a 256-fold increase in activity in a non-aqueous solvent (DMF) [4]. |

| 1994 | DNA Shuffling [4] | In vitro Homologous Recombination: DNA fragments from a gene family are randomly reassembled to create chimeric libraries. | Accelerated evolution: Mimicked sexual recombination. Evolution of a β-lactamase increased host antibiotic resistance by 32,000-fold, far surpassing non-recombinogenic methods [4]. |

| 2018 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry [18] | Collective recognition of Frances Arnold (directed evolution of enzymes), and George Smith and Gregory Winter (phage display). | Field validation: Cemented the transformative impact of directed evolution across basic science and medicine, particularly for generating therapeutic antibodies and green industrial catalysts. |

| Present / Future | Integration with AI & Machine Learning [20] [21] [22] | Semi-rational Design: Machine learning models predict fitness landscapes from sequence-activity data, guiding library design and identifying beneficial mutations. | Enhanced efficiency: Reduces experimental burden by focusing on promising sequence regions. AI tools like AlphaFold (for structure prediction) and RFdiffusion (for de novo design) are creating powerful synergies with directed evolution [21] [22]. |

Experimental Protocols in Directed Evolution

The core process of directed evolution is an iterative cycle, but the specific protocols for library generation and selection have diversified significantly.

The General Directed Evolution Workflow

The universal process involves repeated rounds of three steps: Diversification, Selection (or Screening), and Amplification [18]. The workflow is illustrated below.

Detailed Methodologies for Library Creation and Selection

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Directed Evolution

| Method Category | Specific Protocol | Detailed Methodology | Typical Library Size | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Mutagenesis | Error-Prone PCR [18] [4] | PCR is performed under conditions that reduce fidelity (e.g., unbalanced dNTPs, Mn2+ ions), introducing random point mutations throughout the gene. | 10^4 - 10^6 variants | Broad exploration of local sequence space around a parent sequence. |

| Recombination | DNA Shuffling [4] | A family of homologous genes is digested with DNase I, and the fragments are reassembled in a primer-free PCR, creating chimeric genes. | 10^6 - 10^12 variants | Exploring diversity from natural homologs or beneficial mutants from earlier rounds. |

| Selection | Phage Display [18] | A library of protein variants is displayed on the surface of phage particles. Phages binding to an immobilized target are retained and eluted, and their DNA is amplified. | Up to 10^11 variants | Isolating high-affinity binders (e.g., antibodies, peptides). |

| Screening | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [20] | Cells displaying or expressing protein variants are individually analyzed for a fluorescent signal linked to activity. The top-performing fraction is isolated and sorted. | 10^7 - 10^9 variants per hour | Quantifying and isolating variants based on activity levels when a fluorescent reporter is available. |

| Targeted Mutagenesis | Focused Libraries [18] | Based on structural knowledge or computational predictions, specific residues (e.g., in the active site) are randomized using degenerate codons. | 10^2 - 10^5 variants | Efficiently optimizing a specific region of a protein without the noise of global mutagenesis. |

The Evolutionary Design Spectrum: A Unifying Framework

A modern perspective posits that all biological design processes, from traditional design to directed evolution, exist on a unified evolutionary design spectrum [23]. This framework is defined by two key dimensions: the throughput (number of variants tested per cycle) and the number of generations (design cycles). This spectrum directly informs the trait-based versus directed evolution debate.

Trait-Based (Rational) Design: This approach lies on one end of the spectrum, characterized by low throughput but high prior knowledge exploitation. Engineers use structural and mechanistic information to design specific changes, typically testing a small number of variants in a single, knowledge-driven cycle [18] [23].

Directed Evolution: This approach lies on the other end, characterized by high throughput and high exploration over multiple generations. It requires minimal prior knowledge, relying instead on iterative random variation and selection to discover beneficial traits [18] [23].

Semi-Rational (AI-Guided) Design: This hybrid approach is emerging as a powerful middle ground. It uses machine learning to exploit large datasets (knowledge) to create focused libraries, thereby guiding the exploration process more efficiently. This enhances the power of directed evolution by reducing its reliance on pure randomness and massive screening [20] [21] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful directed evolution experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and biological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | A optimized blend of polymerase and buffer conditions to introduce random mutations during gene amplification [18]. |

| Phage Display Vector | A plasmid engineered for the surface display of peptide/protein fusions on bacteriophages, enabling selection [18]. |

| Fluorescent Substrate/Reporter | A molecule that produces a measurable fluorescent signal upon enzymatic activity, enabling high-throughput screening via FACS or microplate readers [20] [18]. |

| Microfluidic Cell Sorter | Advanced instrumentation that allows for high-throughput, single-cell analysis and sorting based on phenotypic traits, enabling complex selection strategies [20]. |

| In vivo Mutagenesis Strain | Engineered host cells (e.g., E. coli) with hypermutable genomes or inducible mutagenesis systems targeted to a plasmid of interest [20]. |

| Yeast Surface Display System | A eukaryotic platform for displaying protein libraries on the yeast surface, allowing for the selection of well-folded, glycosylated proteins [21]. |

| Loloatin B | Loloatin B|Cyclic Decapeptide Antibiotic|RUO |

| Veldoreotide TFA | Veldoreotide TFA, MF:C62H75F3N12O12, MW:1237.3 g/mol |

The journey of directed evolution, from Spiegelman's minimalist RNA to today's AI-integrated protein engineering platforms, demonstrates a clear trajectory toward increasingly sophisticated and efficient design. The historical comparison reveals that no single methodology is universally superior; rather, the choice between high-exploration directed evolution and high-exploitation trait-based design depends on the available knowledge and the specific engineering goal. The emerging paradigm, however, powerfully synthesizes these approaches. By leveraging computational models to learn from fitness landscapes, modern protein engineers can now design smarter libraries and navigate sequence space with unprecedented precision. This semi-rational, data-driven approach represents the current frontier, optimizing the community of protein variants by intelligently balancing the exploration of new traits with the exploitation of known structural principles.

This guide compares two fundamental approaches in evolutionary optimization: trait-based evolution, which observes how natural communities evolve in response to environmental pressures, and directed evolution, an experimental technique that mimics natural evolution to engineer biomolecules with desired properties. The comparison is framed for researchers aiming to optimize biological systems, from microbial communities to therapeutic proteins.

Core Conceptual Comparison

The table below outlines the foundational principles of each approach.

| Feature | Trait-Based Evolution (Eco-Evolutionary) | Directed Evolution (Protein Engineering) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Studies how heritable functional traits influence fitness and ecosystem function in natural environments [24]. | Harnesses Darwinian principles in a laboratory setting to rapidly evolve biomolecules with enhanced functions [3]. |

| Primary Context | Natural ecosystems and communities (e.g., plant communities, land snails) [24] [2]. | In vitro or in vivo laboratory systems [3]. |

| Driving Force | Natural selection from environmental pressures (e.g., competition, abiotic stress) [2]. | Artificial selection for human-defined objectives (e.g., enzyme activity, drug binding) [3]. |

| Key Metrics | Specific Effect Function (SEF), Specific Response Function (SRF), functional diversity, phylogenetic signal [24]. | Library size, enrichment factor, catalytic efficiency ((k{cat}/Km)), binding affinity ((K_d)) [3]. |

| Typical Workflow | 1. Trait measurement → 2. Environmental correlation → 3. Fitness consequence → 4. Phylogenetic analysis [24] | 1. Library generation → 2. Selection/Screening → 3. Characterization → 4. Iteration [3] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

This section details the standard methodologies for both approaches, providing a blueprint for experimental design.

Trait-Based Community Analysis

This protocol is used to understand how communities assemble and function in response to environmental drivers [24] [2].

- Trait Selection and Measurement: Identify and quantify functional traits relevant to the ecosystem process and environmental driver of interest. For plants, this may include leaf nitrogen content (effect trait) and seed mass (response trait). For animals, it could involve body size or feeding structures [24].

- Environmental Grading: Characterize the environmental gradient across study sites (e.g., nutrient availability, temperature, presence of heavy metals or biocides) [25].

- Community Assessment: Census species abundance and distribution across the environmental gradient.

- Data Integration and Modeling:

- Calculate Specific Effect Function (SEF) and Specific Response Function (SRF) for key species [24].

- Analyze the correlation between SEF and SRF and test for phylogenetic signal to assess ecosystem vulnerability [24].

- Use models to test if trait variance decreases in species-rich communities due to competitive packing [2].

Directed Evolution of a Protein

This general workflow is employed to improve or alter enzyme activity, binding affinity, or stability [3].

- Library Generation: Create genetic diversity in a parent gene sequence.

- Selection or Screening: Identify improved variants from the library.

- High-Throughput Selection: Use methods like phage display or FACS to isolate binders or enzymes with desired activity from large libraries (>10^8 members) [3].

- Lower-Throughput Screening: Screen smaller libraries (<10^4 members) using plate-based assays (e.g., colorimetric or fluorimetric changes) [3].

- Characterization: Purify the hit variants and characterize them using relevant biochemical assays (e.g., kinetics, thermostability).

- Iteration: Use the best-performing variant as a template for subsequent rounds of diversification and selection to cumulatively improve the function.

Experimental Data and Comparison

The following table synthesizes quantitative data and outcomes from studies employing these approaches.

| Approach / Study | Key Experimental Data | Outcome / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Trait-Based: Land Snails (Galápagos) [2] | In communities with higher species diversity, individual species evolved narrower trait breadths (reduced intraspecific variance). | Increased species diversity led to reduced functional diversity due to competitive packing, challenging the assumption that species richness always increases ecosystem function [2]. |

| Trait-Based: Co-Selection [25] [26] | Exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of heavy metals (e.g., Cu, Zn) or biocides (e.g., QACs) selected for bacterial populations with increased antibiotic resistance. | Non-antibiotic environmental contaminants can co-select for antibiotic resistance via co-resistance (linked genes) or cross-resistance (e.g., efflux pumps), highlighting a major risk factor in AMR proliferation [25] [26]. |

| Directed Evolution: General [3] | A single round of error-prone PCR typically creates libraries of 10^6 - 10^10 variants. FACS-based screening can sort >10^8 cells per hour. | Enables exploration of a vast sequence space that is impossible with rational design, allowing for the discovery of unexpected solutions. |

| Directed Evolution: RACHITT [3] | Method yielded a 15-fold increase in crossover frequency compared to earlier DNA shuffling techniques. | Results in higher diversity libraries and more efficient exploration of chimeric protein sequences. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for implementing these evolutionary approaches.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Utilizes a DNA polymerase with low fidelity and biased reaction conditions to introduce random point mutations during gene amplification for directed evolution library generation [3]. |

| Phage Display Library | A collection of filamentous phages, each displaying a different protein variant on its surface. Used for high-throughput selection of high-affinity binders from libraries exceeding 10^9 members [3]. |

| FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter) | An instrument that sorts individual cells based on fluorescence. In directed evolution, it is used to isolate enzyme or binder variants labeled with a fluorescent product or tag [3]. |

| Functional Trait Database | Curated databases (e.g., TRY for plant traits) that provide standardized trait measurements. Used in trait-based studies for large-scale comparative analyses and modeling [24]. |

| Metals & Biocides | Heavy metals (e.g., Copper, Zinc) and biocides (e.g., Quaternary Ammonium Compounds) are used in co-selection studies to apply selective pressure and investigate the evolution of cross-resistance in microbial communities [25] [26]. |

| PROTAC SOS1 degrader-5 | PROTAC SOS1 degrader-5, MF:C45H51F3N8O7, MW:872.9 g/mol |

| (1S,9R)-Exatecan mesylate | (1S,9R)-Exatecan mesylate, MF:C25H26FN3O7S, MW:531.6 g/mol |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The diagrams below illustrate the logical flow of each evolutionary approach.

Trait-Based Eco-Evolutionary Framework

Directed Evolution Workflow

The relationship between a protein's amino acid sequence and its biological function is one of the most fundamental yet poorly understood aspects of molecular biology. Despite decades of research, accurately predicting function from sequence alone remains exceptionally difficult, creating a significant bottleneck in fields ranging from drug development to enzyme engineering. This challenge stems from the highly complex nature of sequence-function relationships, which arises from the intricate interplay between biophysical constraints and evolutionary history [27]. The astronomical vastness of sequence space further complicates this picture—a typical protein several hundred amino acids long represents 20³â°â° possible sequences, a number that exceeds the total atoms in the universe [28]. This review examines why this prediction problem persists, comparing two dominant approaches for navigating this complexity: trait-based rational design and empirical directed evolution. We objectively evaluate their performance through experimental data and methodological analysis, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate strategies for protein engineering challenges.

The Core Mechanisms Underlying Prediction Challenges

Epistasis and Context-Dependent Effects

A primary source of prediction difficulty lies in epistasis, where the effect of a mutation depends on its genetic context. Rather than acting independently, amino acid residues engage in complex, higher-order interactions that profoundly influence protein function [28]. Traditional reference-based analyses, which measure mutational effects relative to a single wild-type sequence, often overestimate epistasis by propagating measurement noise and local idiosyncrasies into high-order interactions [29]. This can lead to unnecessarily complex descriptions of genetic architecture. Reference-free analysis (RFA) addresses this by taking a global perspective, defining amino acid effects relative to the average across all possible sequences rather than a single reference point [29]. Studies implementing RFA reveal that sequence-function relationships are surprisingly simple in many cases, with context-independent amino acid effects and pairwise interactions explaining over 92% of phenotypic variance across 20 experimental datasets [29].

Rugged Fitness Landscapes and Nonlinearity

The presence of epistasis creates rugged fitness landscapes rather than smooth, easily navigable surfaces. These landscapes are characterized by multiple peaks, valleys, and plateaus, making it difficult to predict the functional outcome of multiple simultaneous mutations [28]. This ruggedness arises not only from direct structural contacts between residues but also from indirect effects modulated by ligands, substrates, allostery, cofactors, and conformational dynamics [28]. Additionally, global nonlinearities in the relationship between sequence and function further complicate prediction. Without accounting for these nonlinear transformations, analyses must invoke pervasive complex interactions to explain why mutation effects vary across genetic backgrounds [29]. For example, a stability threshold effect can occur where individually beneficial but destabilizing mutations combine to completely abolish activity [28].

Sparse Determinants and Multi-Functionality

Protein sequence-function relationships exhibit sparse determinism, where a minute fraction of possible amino acids and interactions account for the majority of functional variance [29]. This sparsity makes identification of key determinants challenging, especially with limited experimental data. Furthermore, many proteins exhibit multi-functionality, performing multiple distinct biological roles. The MoonProt database catalogs hundreds of proteins experimentally demonstrated to have more than one function [30]. This multi-functionality often arises from small sequence or structural changes that are difficult to predict a priori. For instance, the enolase superfamily contains evolutionarily related enzymes with similar TIM-barrel folds that catalyze different reactions, including enolases, muconate lactonizing enzymes, and mandelate racemases [30]. Small changes in active site residues are sufficient to alter catalytic specificity, creating prediction challenges even among well-characterized protein families.

Comparative Analysis of Engineering Approaches

Trait-Based Rational Design

Trait-based approaches rely on prior structural and mechanistic knowledge to make informed predictions about which sequence changes will produce desired functions. These methods leverage detailed understanding of protein biochemistry to design variants with improved or altered properties.

Methodological Framework

Trait-based design typically begins with structural analysis to identify key residues influencing target functions, such as active site residues for catalysis or interface residues for binding interactions. Researchers then employ computational modeling to predict the functional consequences of mutations, often using molecular dynamics simulations or energy calculations. Finally, a limited set of designed variants is synthesized and experimentally validated [30]. This approach requires high-quality structural data and robust computational models that accurately capture sequence-structure-function relationships.

Experimental Performance and Limitations

While successful in many applications, trait-based design faces significant limitations. Performance varies considerably depending on the protein system and target function, with particularly poor outcomes for functions lacking clearly correlated structural features [30]. For example, predicting protein-protein interaction sites remains challenging because these interfaces often consist of relatively smooth surface regions without well-conserved motifs [30]. Similarly, many RNA-binding proteins lack canonical RNA-binding domains, making computational prediction of interaction sites difficult. These limitations underscore the fundamental gaps in our understanding of how sequence encodes function.

Directed Evolution Approaches

Directed evolution mimics natural selection in the laboratory, using iterative rounds of diversification and selection to improve protein functions without requiring detailed mechanistic knowledge.

Methodological Framework

The directed evolution cycle begins with the creation of genetic diversity through random mutagenesis, DNA shuffling, or targeted methods like CRISPR-Cas systems [31] [32]. This variant library is then subjected to high-throughput screening or selection to identify individuals with improved functional characteristics. The top-performing variants serve as templates for subsequent rounds of diversification and selection, progressively optimizing the desired function [28] [32]. Unlike trait-based approaches, directed evolution does not require prior structural knowledge, instead relying on functional screening to guide the optimization process.

Experimental Performance and Applications

Directed evolution has demonstrated remarkable success across diverse applications. In agricultural biotechnology, researchers used CRISPR-Cas-mediated directed evolution to develop herbicide-resistant crops by evolving rice acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC) and acetolactate synthase (ALS1) variants [31]. These evolved enzymes conferred resistance while maintaining catalytic function, with specific mutations (P1927F and W2125C in ACC; P171F in ALS1) identified as responsible for the herbicide-tolerant phenotype [31]. Similarly, directed evolution of rice splicing factor SF3B1 generated variants (SGR mutants) resistant to splicing inhibitors herboxidiene and pladienolide B while maintaining splicing functionality [31]. These successes highlight the power of directed evolution to optimize complex functions without detailed structural knowledge.

Machine Learning-Enabled Approaches

Recent advances integrate machine learning with directed evolution, creating hybrid approaches that leverage large-scale sequence-function data.

Methodological Framework

Machine learning methods for protein engineering typically involve training models on deep mutational scanning (DMS) data, which combines high-throughput functional screening with next-generation sequencing to map sequence-function relationships for thousands to millions of variants [33]. These models learn the mapping between sequence and function, enabling prediction of functional outcomes for uncharacterized sequences. Positive-unlabeled learning frameworks have been developed specifically to handle DMS data, which often lacks explicit negative examples [33]. The trained models guide subsequent library design, creating an iterative optimization cycle that reduces experimental burden.

Experimental Performance and Applications

Machine learning approaches have demonstrated excellent predictive performance across diverse protein systems. In one notable application, researchers used learned sequence-function models to design highly stabilized enzymes, successfully extrapolating beyond the training data to create thermostable variants [33]. These methods effectively identify key functional determinants while handling the high dimensionality and correlations inherent to protein sequence data. The GOLabeler method, which integrates multiple data sources using machine learning, significantly outperformed other function prediction algorithms in the critical assessment of functional annotation (CAFA) challenges [30].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Protein Engineering Approaches

| Approach | Key Methodologies | Typical Experimental Throughput | Success Rate | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait-Based Rational Design | Structure-based design, computational modeling, molecular dynamics | Low (10-100 variants) | Variable (high for well-characterized systems) | Requires detailed structural knowledge; poor for complex functions |

| Directed Evolution | Random mutagenesis, DNA shuffling, CRISPR-Cas diversification | Medium to High (10³-10⸠variants) | Consistently high across diverse systems | Limited by screening capacity; can require many iterations |

| Machine Learning-Enabled | Deep mutational scanning, positive-unlabeled learning, neural networks | Very High (10âµ-10â¹ variants in silico) | Increasingly high with sufficient training data | Requires large training datasets; model interpretability challenges |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Representative Studies

| Protein System | Engineering Goal | Trait-Based Results | Directed Evolution Results | Machine Learning Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice SF3B1 [31] | Herbicide resistance | N/A | SGR mutants with full splicing function and drug resistance | N/A |

| Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase [31] | Herbicide resistance | N/A | P1927F and W2125C mutations conferring haloxyfop resistance | N/A |

| GB1 binding protein [32] | Enhanced binding affinity | N/A | N/A | Accurate prediction of optimized combinatorial libraries |

| Multiple enzyme systems [33] | Thermostability | Variable success | N/A | Successful design of stabilized enzymes |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Deep Mutational Scanning Protocol

Deep mutational scanning (DMS) provides comprehensive sequence-function maps by combining high-throughput functional screening with deep sequencing [33]. The protocol begins with library generation, creating variant libraries covering targeted regions through saturation mutagenesis, error-prone PCR, or oligonucleotide synthesis. The library is then subjected to functional screening, applying selective pressure to separate functional from non-functional variants. This is followed by high-throughput sequencing of pre-selection and post-selection populations to quantify variant enrichment. Finally, enrichment analysis calculates fitness scores for each variant based on frequency changes, generating a quantitative sequence-function map [33]. DMS data typically contains only positive and unlabeled examples, necessitating specialized computational approaches like positive-unlabeled learning for accurate modeling [33].

CRISPR-Cas-Mediated Directed Evolution Protocol

CRISPR-Cas systems enable targeted diversification for directed evolution in native genomic contexts [31]. The protocol involves sgRNA library design to target specific gene regions, library delivery into plant cells via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, and CRISPR-Cas editing to generate diverse mutations through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). Edited cells are then subjected to selection pressure (e.g., herbicide application), followed by recovery and analysis of resistant variants [31]. This approach was successfully used to evolve herbicide resistance in rice by targeting the SF3B1 gene, generating splicing factor variants that maintained function while gaining resistance to pladienolide B and herboxidiene [31].

Reference-Free Analysis Protocol

Reference-free analysis (RFA) addresses limitations of traditional reference-based approaches by providing a global perspective on sequence-function relationships [29]. The method involves data collection from combinatorial mutagenesis studies, global mean calculation across all variants, first-order effect estimation for each amino acid state as the difference between sequences containing that state and the global mean, and epistatic effect calculation for state combinations as differences between observed and expected means based on lower-order effects [29]. RFA can be accurately estimated using least-squares regression even with missing data and provides the most efficient explanation of sequence-function relationships by maximizing variance explained at each epistatic order [29].

Visualizing Sequence-Function Relationship Concepts

Protein Fitness Landscape Complexity

Directed Evolution Workflow

Reference-Based vs Reference-Free Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Sequence-Function Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversification Technologies | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, MAGE, CRISPR-Cas systems | Generate genetic variation for functional screening | Mutation rate, library diversity, bias introduction |

| Screening Systems | FACS, microfluidics, growth selection, phage display | Identify functional variants from libraries | Throughput, sensitivity, false positive/negative rates |

| Sequence-Function Mapping | Deep mutational scanning, phage-assisted continuous evolution | Comprehensive analysis of variant effects | Coverage, quantitative accuracy, statistical power |

| Computational Tools | Positive-unlabeled learning, reference-free analysis, neural networks | Model sequence-function relationships | Data requirements, interpretability, predictive accuracy |

| Specialized Databases | UniProt, PDB, MoonProt, DisProt, Enzyme Portal | Access to sequence, structure, and function data | Coverage, annotation quality, update frequency |

| 2'-Deoxyadenosine-13C10 | 2'-Deoxyadenosine-13C10, MF:C10H13N5O3, MW:261.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Me-Tet-PEG5-COOH | Me-Tet-PEG5-COOH, MF:C24H35N5O8, MW:521.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The relationship between protein sequence and function remains difficult to predict a priori due to epistasis, rugged fitness landscapes, and sparse functional determinants. Our comparative analysis reveals that while trait-based rational design provides mechanistic insights for well-characterized systems, directed evolution offers more consistent success across diverse protein engineering challenges. Machine learning approaches are rapidly bridging this divide, leveraging large-scale experimental data to build predictive models that capture complex sequence-function relationships. The emerging paradigm integrates these approaches, using directed evolution to generate functional data and machine learning to extract generalizable principles. This integrated framework promises to accelerate protein engineering for therapeutic development, industrial applications, and fundamental biological research, gradually transforming the sequence-function relationship from a fundamental mystery to a tractable engineering problem.

Toolkits and Techniques: Implementing Directed Evolution and Trait Analysis

Genetic diversification is a cornerstone of biological research and biotechnology, enabling the exploration of gene function and the evolution of proteins with novel traits. The methods to achieve this diversification broadly fall into two categories: random, untargeted approaches (like error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling) and precise, targeted approaches (exemplified by CRISPR-Cas systems). This guide provides an objective comparison of these three key techniques—Error-Prone PCR, DNA Shuffling, and CRISPR-Cas Systems—framed within the broader thesis of trait-based versus directed evolution approaches for optimizing biological functions. We summarize their mechanisms, applications, and experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their community optimization research.

The following table offers a high-level comparison of the three genetic diversification methods.

| Feature | Error-Prone PCR | DNA Shuffling | CRISPR-Cas Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Introduces random point mutations during PCR amplification using error-prone conditions [34]. | Recombines fragments from related DNA sequences in vitro to create chimeric genes [35]. | Uses a programmable RNA-guided Cas nuclease to make targeted double-strand breaks in the genome, engaging cellular repair mechanisms to introduce changes [36] [37]. |

| Primary Type of Diversity | Point mutations, small insertions/deletions [34]. | Recombination of existing mutations and gene homologs; can create novel combinations of sequences from parent genes [35]. | User-defined mutations via HDR; random indels via NHEJ; can be targeted to specific chromosomal loci [36]. |

| Typical Library Size | Limited by cloning efficiency [34]. | Can rapidly generate very large libraries (e.g., millions of clones) [35]. | Limited by HDR efficiency in many systems, but sgRNA libraries can offer extensive coverage [36]. |

| Key Advantage | Technically simple, no structural knowledge of protein required. | Rapidly recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parents. | Enables precise, chromosomal diversification at the native locus, preserving endogenous regulation [36]. |

| Major Limitation | Mutations are random and largely blind to function. | Requires sequence homology or common restriction sites for some methods [35]. | Lower efficiency of HDR in mammalian cells; risk of unintended on-target structural variations [36] [38]. |

| Tyk2-IN-15 | Tyk2-IN-15|Potent TYK2 Inhibitor|For Research | Bench Chemicals | |

| Ebov-IN-6 | EBOV-IN-6 | EBOV-IN-6 is a benzothiazepine compound with anti-Ebola virus (EBOV) research activity (IC50 = 10 μM). This product is for research use only and not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Below are the standardized experimental workflows for each method, from library generation to variant screening.

Error-Prone PCR Workflow

- Step 1: Library Generation. The gene of interest is amplified by PCR under "sloppy" conditions. This involves using a polymerase with low fidelity, increasing the concentration of MgClâ‚‚, adding MnClâ‚‚, and using unequal concentrations of the four dNTPs. These conditions promote misincorporation of nucleotides during amplification, resulting in a pool of PCR products with random point mutations [34].

- Step 2: Cloning and Transformation. The mutated PCR products are then cloned into a suitable plasmid expression vector. This library of plasmids is transformed into a bacterial host (e.g., E. coli) to create a library of clones, each expressing a different variant of the gene [34].

- Step 3: Screening/Selection. The transformed library is screened using high-throughput assays (e.g., for enzyme activity, ligand binding, or fluorescence) to identify clones with the desired improved or altered function [34].

DNA Shuffling Workflow

- Step 1: Fragmentation. Multiple parent genes (which can be natural homologs or pre-mutated variants) are physically fragmented. This can be done enzymatically using DNase I [35] [39] or via more controlled methods like Nucleotide Exchange and Excision Technology (NExT), which uses the incorporation of uracil and subsequent excision to generate fragments [39].

- Step 2: Reassembly. The fragments are mixed and subjected to a primer-less PCR. Due to sequence homologies, fragments from different parents can anneal to each other. The DNA polymerase then extends these overlapping fragments, reassembling them into full-length, chimeric genes [35].

- Step 3: Cloning and Selection. The reassembled genes are amplified with primers and cloned into an expression vector. The resulting library, which contains hybrids recombining sequences from all parent genes, is then screened for variants with enhanced or novel properties [35].

CRISPR-Cas Mediated Chromosomal Diversification Workflow

- Step 1: Component Design. A single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is designed to target the specific genomic locus of interest. A library of donor DNA templates (HDR templates) is synthesized, containing the desired diversified sequences (e.g., saturated mutations, barcodes, or coding variants) flanked by homologous arms [36].

- Step 2: Delivery and Cleavage. The sgRNA, Cas9 nuclease, and the HDR template library are co-delivered into the target cells. The Cas9-sgRNA complex creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the chromosome at the target site [36] [37].

- Step 3: Homology-Directed Repair. The cell's repair machinery uses the supplied donor DNA library as a template for HDR, thereby integrating the diversified sequences directly into the native chromosomal location. This ensures the variants are expressed under endogenous regulatory control [36].

- Step 4: Functional Screening. The population of edited cells, now a library of genetic variants at the target locus, can be subjected to a selective pressure (e.g., a drug, growth condition, or fluorescent assay). Variants with enhanced function are enriched, and their sequences can be identified via next-generation sequencing [36].

Performance and Quantitative Data Comparison

The tables below summarize key performance metrics and experimental data for these methods, illustrating their practical capabilities and limitations.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Genetic Diversification Methods

| Method | Diversity Introduced | Typical Mutation Rate/ Efficiency | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Point mutations (transitions, transversions), small indels [34]. | Error rate can be tuned up to ~2% per base [34]. | Evolving individual proteins for improved stability, activity, or altered substrate specificity [34]. |

| DNA Shuffling | Recombination of point mutations and homologous blocks from multiple parent genes [35]. | Can generate libraries of >10ⴠto 10ⶠclones; low background mutation rate (e.g., 0.1% with NExT) [39]. | Rapidly combining beneficial mutations from different homologs; family shuffling to evolve complex traits like herbicide detoxification [35]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | User-defined single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or small sequences integrated via HDR; random indels via NHEJ [36]. | HDR efficiency is variable and often low (e.g., 0.2% - 3.3% in mammalian cells); can be increased with small molecules, but this may raise SV risk [36] [38]. | Saturation genome editing to map variant effects; CasPER for directed evolution of pathways (11-fold yield increase reported); gene therapy [36] [38]. |

Table 2: Documented Experimental Outcomes from Literature

| Method | Experimental System | Reported Outcome | Reference & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Shuffling | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene | Successful shuffling of truncated CAT variants with an average parental fragment size of 86 bp and a low mutation rate (0.1%). | NExT DNA shuffling methodology [39]. |

| CRISPR-HDR (Saturation Editing) | Human HAP1 cells | Efficiency of saturation editing for exons in genes like BRCA1 ranged from 0.2% to 3.33%. | Functional profiling of disease-associated genes [36]. |

| CRISPR-HDR (CasPER) | Yeast Mevalonate Pathway | Integration of 300-600 bp donor sequences with >98% efficiency, leading to an 11-fold increase in isoprenoid production after selection. | Directed evolution of endogenous yeast genes [36]. |

Critical Considerations for Research Applications

Safety and Limitations: The Case of CRISPR-Cas

While revolutionary, CRISPR-Cas systems carry specific risks that must be accounted for in experimental design, especially for therapeutic applications. Beyond well-known off-target effects, a pressing concern is the introduction of on-target structural variations (SVs). These include large deletions (kilobase- to megabase-scale), chromosomal translocations, and other complex rearrangements [38]. Critically, strategies to improve HDR efficiency, such as using DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648), can dramatically increase the frequency of these SVs—by a thousand-fold for some translocations [38]. Furthermore, traditional short-read amplicon sequencing often fails to detect these large deletions, leading to an overestimation of precise HDR efficiency [38]. Therefore, comprehensive genomic integrity checks using long-read sequencing or dedicated SV-detection assays (like CAST-Seq) are recommended for rigorous safety assessment [38].

Integration in Trait-Based vs. Directed Evolution Frameworks

The choice of diversification method aligns with different ecological optimization strategies:

- Trait-Based Approaches leverage rational design by assembling communities from members with known, complementary traits. This is analogous to using CRISPR for precise, hypothesis-driven saturation editing to understand gene function [36] [9].

- Directed Evolution Approaches remain agnostic to mechanism, instead using iterative rounds of diversification and selection to find high-performing variants or communities. Error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling are classic tools for this, mimicking the evolutionary process of mutation and recombination [9] [34] [35]. CRISPR methods like CasPER now bring the power of targeted, chromosomal diversification to this paradigm [36].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions crucial for implementing these genetic diversification methods.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Genetic Diversification Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase & Sloppy Buffer | Enzyme and optimized buffer system for performing error-prone PCR. Contains elevated Mg²âº, Mn²âº, and unbalanced dNTPs to promote nucleotide misincorporation [34]. | Random mutagenesis of a gene to create a variant library for enzyme evolution. |

| DNase I or NExT Reagents | Enzymes for fragmenting DNA. DNase I randomly cleaves DNA, while NExT (using dUTP incorporation, UDG, and piperidine) offers a more controllable fragmentation pattern [35] [39]. | Initial step in DNA shuffling to create fragments for recombination. |

| Cas9 Nuclease (Wild-type & HiFi) | Effector protein that creates a double-strand break at a DNA target specified by the sgRNA. High-fidelity (HiFi) variants reduce off-target editing [36] [38] [37]. | Targeted chromosomal gene disruption (KO) or diversification via HDR. |

| sgRNA Library | A pooled collection of single-guide RNAs designed to target multiple genomic sites or to cover a specific gene region comprehensively [36]. | Genome-wide screens or saturation editing of a specific gene. |

| HDR Donor Template Library | A pool of single or double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing the variant sequences to be integrated, flanked by homology arms matching the target locus [36]. | Introducing a library of specific mutations (e.g., all possible amino acid changes) into a genomic locus. |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitor (e.g., AZD7648) | Small molecule inhibitor of the NHEJ DNA repair pathway. Used to tilt the balance of DSB repair towards HDR, thereby increasing editing efficiency [38]. | Use with caution. Boosts HDR rates but significantly increases risk of large structural variations [38]. |

Error-Prone PCR, DNA Shuffling, and CRISPR-Cas Systems each offer distinct pathways for genetic diversification, catering to different research needs. The choice between them hinges on the core objective: whether the aim is broad, random exploration of sequence space or precise, targeted hypothesis testing. As the field of synthetic biology and community optimization advances, the integration of robust traditional methods like DNA shuffling with the precision of CRISPR-Cas systems promises to be a powerful strategy. This hybrid approach can leverage the strengths of both directed evolution and rational, trait-based design to engineer biological systems with unprecedented control and functionality. Researchers must carefully weigh the trade-offs in precision, efficiency, and safety—particularly the risk of structural variations with CRISPR—when designing their experimental pipelines.

For decades, random mutagenesis served as the cornerstone of protein engineering, mimicking natural evolution through untargeted genetic diversification and phenotypic screening. While successful, this approach explores sequence space inefficiently, often requiring immense screening efforts and frequently failing to identify optimal mutations due to its undirected nature. The field has progressively shifted towards more precise, knowledge-driven strategies. Site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM) and other targeted evolution methodologies now empower researchers to conduct systematic, focused investigations into protein function and stability, leading to more efficient engineering of biocatalysts, therapeutics, and research tools [40] [41]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these targeted strategies against classical random mutagenesis, providing a framework for selecting the optimal approach for community optimization and drug development research.

Methodological Comparison: Core Techniques and Workflows

Fundamental Principles

- Random Mutagenesis introduces mutations randomly throughout a gene or genome using methods like error-prone PCR or chemical mutagens. It requires no prior structural or mechanistic knowledge but demands high-throughput screening to find rare beneficial mutations amid predominantly neutral or deleterious ones [42].

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) is a targeted technique that systematically substitutes a single codon (or set of codons) with all possible amino acids at that position. This creates a comprehensive library for a specific region, allowing researchers to exhaustively map the sequence-function relationship at defined sites [43] [41].

- Semi-Rational Design leverages bioinformatics and structural biology data to identify key "hotspot" residues for mutagenesis. This approach uses information from multiple sequence alignments, phylogenetic analysis, or protein structures to design small, functionally rich libraries, thereby minimizing screening effort while maximizing the potential for improvement [40].

Experimental Workflows

The fundamental difference between these strategies is visualized in their experimental pathways. The diagram below illustrates the key steps involved in random mutagenesis versus the more streamlined site-saturation and semi-rational approaches.

Performance and Outcome Comparison

The theoretical advantages of targeted strategies are borne out in direct experimental comparisons. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and documented outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Mutagenesis Strategies