Trophic Cascades and Biogeochemical Feedback Loops: Integrating Top-Down Control and Nutrient Cycling in Ecosystem Science

This article synthesizes current research on the interconnected dynamics of trophic cascades and biogeochemical feedback loops, exploring how predator-prey interactions fundamentally influence nutrient cycling and ecosystem function.

Trophic Cascades and Biogeochemical Feedback Loops: Integrating Top-Down Control and Nutrient Cycling in Ecosystem Science

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the interconnected dynamics of trophic cascades and biogeochemical feedback loops, exploring how predator-prey interactions fundamentally influence nutrient cycling and ecosystem function. It addresses the foundational theories of top-down and bottom-up control, examines methodologies for quantifying these complex relationships, and investigates the challenges in predicting outcomes in diverse ecosystems. By comparing evidence across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine systems, this review highlights the critical role of apex predators in maintaining biogeochemical equilibrium and discusses the implications of trophic downgrading for ecosystem stability and function in the context of global anthropogenic change.

Theoretical Foundations: Unraveling Top-Down Control and Nutrient Pathways

The trophic cascade is a fundamental ecological concept describing the powerful indirect interactions that can control entire ecosystems. Formally defined, it occurs when predators limit the density and/or behavior of their prey, thereby enhancing the survival of the next lower trophic level, creating reciprocal changes in relative populations that ripple through food chains [1] [2]. This phenomenon triggers a series of reciprocal changes in the relative populations of predator and prey through a food chain, which can result in dramatic changes in ecosystem structure and nutrient cycling [1]. The concept has evolved significantly since its early formulations, transforming from a seemingly straightforward hypothesis about predator control of herbivores to a nuanced understanding of complex ecological interactions with implications for ecosystem management, conservation biology, and climate science.

The intellectual genesis of trophic cascade theory emerged from the seminal work of Nelson Hairston, Frederick Smith, and Lawrence Slobodkin in 1960—often referred to as the HSS hypothesis or the "green world hypothesis" [3]. They proposed that the Earth remains visibly green because predators regulate herbivore populations, preventing them from consuming all available vegetation [3] [4]. This counteracted the prevailing view that plant production was controlled primarily by physical and chemical factors like solar radiation, climate, and nutrient supply [1]. While physical and chemical factors remain important, we now understand that producer communities and their metabolic rates are also significantly influenced by trophic cascades [1].

Historical Development and Theoretical Underpinnings

The Green World Hypothesis and Its Progenitors

The green world hypothesis, first proposed in a 1957 course by Frederick Edward Smith at the University of Michigan, presented a revolutionary perspective on ecosystem regulation [3]. Hairston, Smith, and Slobodkin formally articulated this hypothesis in 1960, arguing that the world appears green because higher trophic levels control herbivore abundance through predation [3] [2]. Their central premise was that herbivores must not be food-limited given the abundance of green material on Earth, but are instead limited by predators that keep their populations and negative impacts on plants in check [2]. This established a tri-trophic interaction as a key regulatory mechanism in ecosystems.

The HSS model faced immediate challenges from alternative perspectives, particularly the plant self-defense hypothesis, which proposed that plants are not entirely consumed by herbivores primarily because of their adaptations against herbivory, such as thorns, toxicity, and cellulose [3]. This chemically-mediated, bottom-up view suggested that most plants have "won" the predator-prey arms race and are heavily defended, therefore remaining free from significant enemy attack [2]. This fundamental debate between top-down and bottom-up control continues to inform ecological research, with the current understanding acknowledging that both forces operate simultaneously in most ecosystems [5].

Terminology and Conceptual Refinement

The term "trophic cascade" itself was coined by American zoologist Robert Paine in 1980 to describe reciprocal changes in food webs caused by experimental manipulations of top predators [1]. Paine's earlier experiments in 1966 with Pisaster ochraceus sea stars demonstrated their role as a keystone species in regulating mussel populations in intertidal zones, providing crucial empirical support for the concept of top-down control [3]. Paine's work illustrated that predator removal could dramatically reduce biodiversity, fundamentally altering ecosystem structure.

Subsequent theoretical work expanded these concepts beyond simple three-level food chains. Lauri Oksanen argued that the top trophic level in a food chain increases the abundance of producers in food chains with an odd number of trophic levels but decreases producer abundance in chains with an even number of trophic levels [4]. He further proposed that the number of trophic levels in a food chain increases as ecosystem productivity increases, adding sophistication to the original HSS model [4].

Table: Key Historical Developments in Trophic Cascade Theory

| Year | Researcher(s) | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Hairston, Smith, Slobodkin (HSS) | Formulated Green World Hypothesis | Proposed predators as primary regulators preventing herbivores from consuming all vegetation |

| 1966 | Robert Paine | Experimental demonstration with Pisaster sea stars | Introduced keystone species concept; empirical evidence for top-down control |

| 1980 | Robert Paine | Coined term "trophic cascade" | Provided precise terminology for the phenomenon |

| 1980s-1990s | Various researchers | Experimental demonstrations in freshwater lakes | Confirmed trophic cascades control phytoplankton biomass and nutrient cycling |

| 2000s-Present | Multiple research teams | Documentation in terrestrial ecosystems and climate connections | Expanded understanding to complex food webs and climate feedbacks |

Classic Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Aquatic Ecosystems: Foundational Demonstrations

The earliest and most definitive empirical demonstrations of trophic cascades emerged from aquatic ecosystems during the 1980s and 1990s. A series of whole-ecosystem experiments involved adding or removing top carnivores, such as bass (Micropterus) and yellow perch (Perca flavescens), from freshwater lakes [1]. These manipulative experiments demonstrated that trophic cascades controlled biomass and production of phytoplankton, recycling rates of nutrients, the ratio of nitrogen to phosphorus available to phytoplankton, activity of bacteria, and sedimentation rates [1]. Because these cascades affected rates of primary production and respiration by entire lakes, they influenced the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen between the lake and the atmosphere [1].

One of the most cited examples involves the sea otter (Enhydra lutris) in North Pacific coastal ecosystems. Research by James Estes and colleagues demonstrated that where sea otter populations persisted, they suppressed the density and biomass of herbivorous sea urchins, indirectly promoting the abundance of kelp forests [1] [2]. In contrast, at sites where sea otters had been extirpated by the fur trade, sea urchin populations expanded dramatically, creating extensive "urchin barrens" characterized by near-complete elimination of kelp [1] [4] [2]. As sea otter populations recovered in recent decades, predictable changes occurred: reduced urchin densities followed by increased kelp biomass, demonstrating whole-ecosystem recovery with predator reinstatement [2].

Terrestrial Ecosystems: Complexity and Controversy

Although early documented trophic cascades primarily occurred in aquatic systems, subsequent research has identified them in terrestrial ecosystems, albeit often with greater complexity. The reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus) to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s represents one of the most publicized—and debated—examples of a potential terrestrial trophic cascade [6] [4]. Early observations suggested that wolf restoration led to reduced elk populations and altered behavior, subsequently allowing recovery of aspen (Populus tremuloides), willow (Salix spp.), and other woody vegetation that elk had overbrowsed during the wolves' absence [4] [2].

However, this interpretation has faced substantial scientific scrutiny. Recent comprehensive analyses of over 170 studies reveal a more complex picture [6]. The Yellowstone ecosystem is characterized by multiple influential factors beyond wolf predation, including human hunting outside park boundaries, the presence of other predators like grizzly bears and cougars, and the impact of bison—which are largely invulnerable to wolf predation—on vegetation [6]. Furthermore, environmental constraints like drought and changes in hydrology due to the historical loss of beavers have also shaped vegetation recovery [6]. This complexity illustrates the challenge of establishing clear cause-and-effect relationships in open, multifaceted ecosystems subject to numerous simultaneous influences [6].

Table: Comparative Trophic Cascade Strength Across Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Key Species | Cascade Strength | Mediating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater Lakes | Piscivorous fish → Zooplanktivorous fish → Zooplankton → Phytoplankton | Strong | Food web simplicity; fast algal growth rates |

| Marine Kelp Forests | Sea otters → Sea urchins → Kelp | Strong | Keystone predator role; limited herbivore diversity |

| Terrestrial Forests | Wolves → Elk → Aspen/Willow | Variable/Moderate | Multiple predator species; prey behavioral adaptations; plant defenses |

| Tropical Systems | Birds/Anthropods → Herbivorous insects → Plants | Variable | High biodiversity; complex food webs; omnivory |

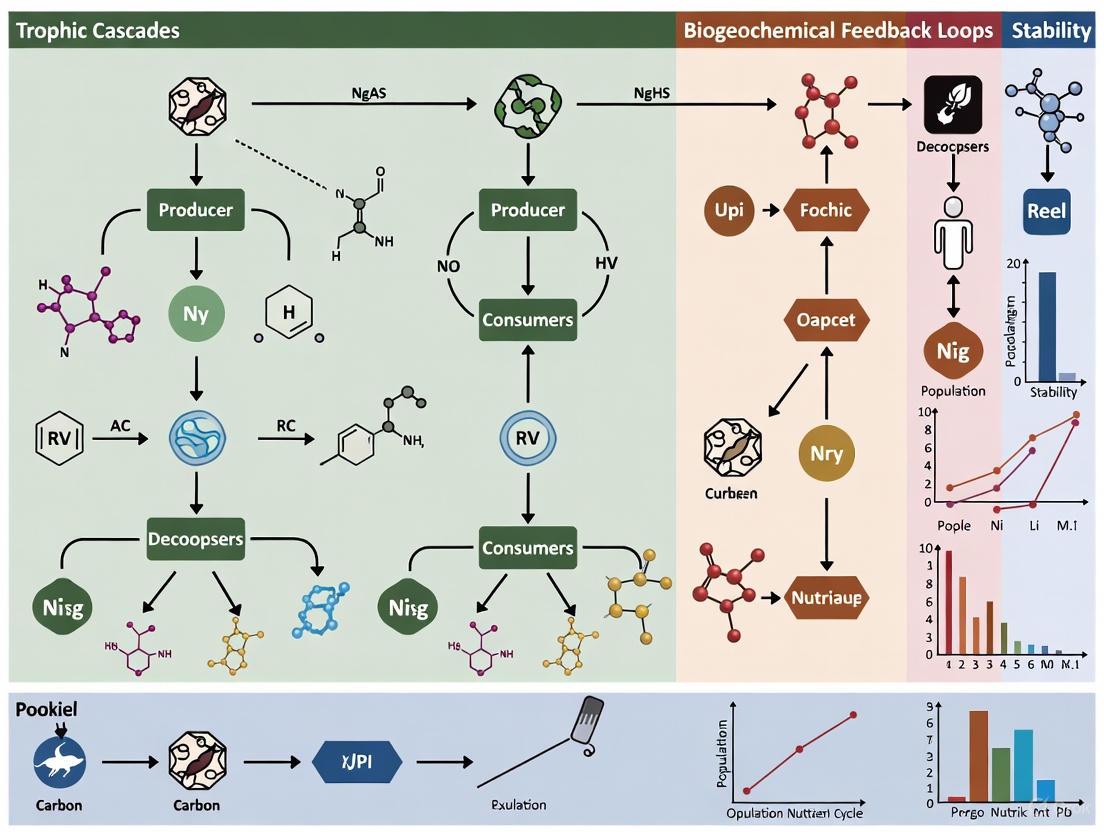

Figure 1: Climate Feedback Loop Involving Trophic Cascades

Modern Paradigms: Complexity, Climate, and Controversies

Beyond Simple Linear Chains: Food Web Complexity

Contemporary understanding has moved beyond viewing trophic cascades as simple linear food chains to recognizing them as complex interactions within broader food webs. The initial HSS model proposed essentially three-level food chains, but we now understand that food web structure significantly influences cascade strength and manifestation [4]. Ecosystems with high species diversity, multiple predator species, and omnivory tend to exhibit dampened trophic cascades compared to simpler systems with linear feeding relationships [4] [2].

This complexity is evident in the phenomenon of mesopredator release, which occurs when the removal of top carnivores allows medium-sized predators to rapidly increase, triggering their own cascading effects [1]. For example, the systematic decline of cougars and wolves across North America during the 20th century facilitated population explosions of mesopredators like coyotes, red foxes, and raccoons [1]. Similarly, the decline of large sharks in the oceans has allowed smaller-bodied sharks and rays to increase, each with consequences for lower trophic levels [1]. These examples illustrate how trophic cascades can involve multiple predator levels with complex interactive effects.

Trophic Cascades and Climate Change Feedbacks

Emerging research reveals profound interconnections between trophic cascades and climate change, with each influencing the other in potentially accelerating feedback loops [5]. Climate change affects trophic cascades through multiple pathways: by forcing species range shifts that create novel species assemblages and interactions, causing phenological mismatches between predators and prey, and increasing the frequency of extreme weather events that disrupt established feeding relationships [5]. For instance, research has documented that reduced winter duration in Montana causes phenological mismatch between seasonal coat color changes in snowshoe hares and snow cover, increasing their vulnerability to predation [5].

Conversely, trophic cascades can significantly influence climate change processes through their effects on carbon cycling and storage [5]. The recovery of sea otters in Pacific coastal ecosystems, by promoting kelp forest growth, enhances carbon sequestration in marine biomass [4]. Similarly, predator-mediated protection of terrestrial vegetation can maintain or increase carbon stocks in forests and other ecosystems [5]. These connections demonstrate that treating climate change and "trophic downgrading" (the loss of apex predators) as isolated phenomena is inadequate—they must be addressed as intertwined challenges [5].

Contemporary Scientific Debates

The field continues to evolve with active scientific debates regarding the prevalence and strength of trophic cascades across different ecosystem types. The question of whether aquatic ecosystems generally exhibit stronger trophic cascades than terrestrial systems remains discussed [3] [2]. Some researchers have suggested that aquatic systems may be more susceptible due to simpler food webs and the prevalence of fast-growing, poorly defended primary producers (phytoplankton and algae) compared to the often chemically defended perennial plants dominating terrestrial systems [2].

The ongoing reevaluation of the Yellowstone wolf reintroduction effects illustrates the continuing scientific dialogue. While early, simplified media accounts presented a straightforward narrative of wolves "restoring" the ecosystem, more recent research emphasizes the complexity of interacting factors [6]. A 2025 comment in a scientific journal even questioned the methodological rigor of certain analyses claiming strong cascading effects, highlighting that willows in Yellowstone have shown limited recovery despite wolf reintroduction [7]. This underscores that in open, complex ecosystems with multiple herbivore species and environmental constraints, straightforward trophic cascades may be masked or dampened [6].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Classic Experimental Designs

The foundational evidence for trophic cascades comes from a variety of rigorous experimental approaches. Whole-ecosystem manipulations have been particularly influential, especially in aquatic environments. These experiments involve intentionally adding or removing top predators from contained systems like lakes and monitoring the responses across multiple trophic levels [1]. For example, researchers have manipulated fish populations in lakes to demonstrate how piscivorous fish reduce planktivorous fish abundance, releasing zooplankton from predation and increasing their grazing pressure on phytoplankton, ultimately resulting in clearer water [1] [4].

Predator exclusion experiments represent another key methodology. By establishing paired treatment and control areas with and without predators (often using fences, cages, or natural barriers), researchers can quantify predation effects on herbivore behavior and density, as well as subsequent impacts on plant communities [2]. This approach has been widely used in both terrestrial and marine environments, from fencing studies with deer and elk to caging experiments with starfish and urchins in intertidal zones [4] [2].

Modern Technological Innovations

Contemporary trophic cascade research increasingly leverages advanced technologies that enable more precise and comprehensive monitoring of complex ecological interactions. GPS telemetry allows detailed tracking of predator and prey movements, revealing how the "landscape of fear" influences herbivore foraging behavior and spatial patterns of plant damage [6]. Genetic sampling techniques, including environmental DNA (eDNA), provide non-invasive methods for monitoring species presence and diet composition [6]. Camera traps and bioacoustic monitoring systems enable continuous, automated surveillance of animal activities across large spatial and temporal scales [6].

These technological advances are particularly valuable for studying the restoration of large carnivores, as they help researchers document subtle behavioral responses and trophic interactions that would be difficult to detect through traditional observation methods [6]. The integration of these tools with experimental manipulations strengthens causal inference in complex field settings where controlled experiments are challenging.

Table: Essential Research Toolkit for Studying Trophic Cascades

| Methodology | Application in Trophic Cascade Research | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-ecosystem manipulation | Adding/removing predators from contained systems | Demonstrated causal links across multiple trophic levels in aquatic systems |

| Predator exclusion experiments | Using fences, cages, or natural barriers | Quantified predation effects on herbivore behavior and plant communities |

| GPS telemetry | Tracking animal movements and spatial patterns | Revealed behaviorally-mediated cascades via "landscape of fear" |

| Stable isotope analysis | Tracing energy flow and food web connections | Elucidated trophic positions and feeding relationships |

| Long-term monitoring | Repeated sampling of populations over decades | Documented ecosystem responses to predator recovery/decline |

| Remote sensing & GIS | Mapping vegetation changes over large areas | Detected landscape-scale impacts of predator-mediated herbivory |

Figure 2: Modern Research Workflow for Studying Trophic Cascades

Applications in Conservation and Ecosystem Management

Biomanipulation for Ecosystem Restoration

The principles of trophic cascades have been directly applied to ecosystem management through approaches such as biomanipulation, particularly in freshwater lakes [1]. This management practice involves intentionally removing or adding species to trigger trophic cascades that improve water quality [1]. The most common application involves reducing populations of plankton-eating fish to enhance zooplankton grazing pressure on phytoplankton, particularly to control harmful algal blooms like toxic blue-green algae [1]. In some shallow lakes, managers have removed bottom-feeding fish to promote the growth of rooted vegetation, which stabilizes sediments and increases water clarity [1]. These approaches demonstrate how understanding of trophic cascades can provide practical tools for addressing environmental problems.

Predator Restoration and Rewilding

The intentional restoration of apex predators represents a major application of trophic cascade theory in conservation biology. Efforts to recover wolf populations in North America and Europe, reintroduce tigers in protected areas, and conserve African lions all draw upon the understanding that these predators may help regulate entire ecosystems [6]. However, recent research emphasizes that outcomes are context-dependent and less predictable than often assumed [6]. Restoration efforts are ecologically beneficial for increasing biodiversity and ecosystem complexity, but they may not produce simple, predictable trophic cascades, especially in human-modified landscapes where other factors constrain ecological dynamics [6].

This nuanced perspective suggests that while predator restoration is valuable, the most effective conservation strategy is to prevent the loss of large carnivores in the first place [6]. As one researcher noted, "putting them back, while useful to do, could take 50 to 100 years or more to really restore what was lost" [6]. This highlights the importance of maintaining intact predator-prey relationships rather than attempting to reassemble them after they have been disrupted.

The concept of trophic cascades has evolved substantially from Hairston's original "green world hypothesis" to encompass complex interactions within diverse ecosystems. The fundamental insight that predators can indirectly influence plant communities and ecosystem processes through cascading interactions remains well-established, but contemporary research reveals significant variation in the strength and manifestation of these effects across different ecological contexts [1] [6] [2]. Future research priorities include better understanding the interplay between temperature-induced changes in predator-prey relationships, carbon cycling implications of trophic cascades, species range shift effects, and the impacts of extreme weather and wildfire events on food web dynamics [5].

Rapidly improving technologies such as GPS telemetry, genetic sampling, camera traps, and bioacoustic monitoring promise to advance our understanding by enabling more comprehensive tracking of predator and prey populations and their interactions [6]. Furthermore, integrating trophic cascade research with climate science will be essential for developing effective ecosystem management strategies in an era of rapid global change [5]. As the field moves forward, recognizing that trophic cascades operate within complex networks of species interactions and environmental constraints will lead to more realistic models and more effective conservation applications.

Biogeochemical cycles describe the movement and transformation of chemical elements through different reservoirs within the Earth system, including the atmosphere, hydrosphere (water and ice), biosphere (life), and lithosphere (rock) [8]. These cycles keep essential elements available to plants and other organisms, forming the fundamental metabolic pathways of ecosystems [9]. Unlike energy, which flows unidirectionally through ecosystems, matter is conserved and recycled according to the law of conservation of mass [9]. The cycling of key elements—particularly carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus—is interconnected, with human activities now significantly altering these natural pathways through agricultural practices, fossil fuel combustion, and wastewater discharge [10] [11].

The interplay between biogeochemical cycles and trophic dynamics creates complex feedback loops that regulate ecosystem functioning. Trophic cascades—the indirect effects of carnivores on plants mediated by herbivores—represent a crucial mechanism through which biological interactions influence nutrient cycling [12] [13]. This review examines biogeochemical cycles through the lens of trophic cascades and their associated feedback loops, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for investigating these critical ecosystem processes.

Core Elemental Cycles

The Carbon Cycle

The carbon cycle is comprised of interconnected rapid and long-term cycles that dynamically exchange carbon between active and geological reservoirs [9]. Carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚) represents the primary atmospheric phase of carbon, where it functions as a greenhouse gas that absorbs heat and contributes to the regulation of Earth's temperature [8].

Table 1: Major Carbon Fluxes and Reservoirs in the Biosphere

| Reservoir/Process | Description | Scale/Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric COâ‚‚ | Primary atmospheric phase of carbon | Increased from ~280 ppm to >423 ppm since industrial revolution [14] |

| Terrestrial Biosphere Uptake | Carbon transfer via photosynthesis | Critical pathway for atmospheric carbon sequestration [8] |

| Geological Reservoirs | Carbonate rocks and fossil fuels | Largest carbon reservoir on Earth [9] |

| Oceanic Uptake | COâ‚‚ dissolution and carbonate formation | Carbonate ions (CO₃²â») form calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) for marine organism shells [9] |

| Inland Water Bodies | Processing, transport, and sequestration | Disproportionately significant despite covering ~1% of Earth's surface [14] |

Carbon cycles rapidly between organisms and the atmosphere through photosynthesis and respiration. Photosynthesis removes COâ‚‚ from the atmosphere to produce energy-rich organic molecules, while respiration returns it through energy-releasing processes [9]. This reciprocal relationship means significant disruption of one process can dramatically affect atmospheric COâ‚‚ levels [9].

Carbon also cycles slowly between land and ocean through geological processes. Weathering of terrestrial rocks releases carbon into soil, where it can be washed into water bodies [9]. In oceans, carbon precipitates as calcium carbonate in marine organism shells, forming sediments that eventually become limestone through geological compression [9]. Plate tectonics subsequently subducts these carbonate sediments, melting and returning them to the surface via volcanic activity [9].

Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycles

Nitrogen and phosphorus are essential macronutrients with distinctly different biogeochemical cycles. Nitrogen, though abundant in the atmosphere as Nâ‚‚, must be converted to reactive forms via biological or industrial fixation [11]. The Haber-Bosch process now contributes more reactive nitrogen to ecosystems than natural biological fixation, dramatically disrupting nitrogen cycles [11]. In contrast, phosphorus derives exclusively from finite phosphate rock, with no known substitute for its vital functions in DNA synthesis, membrane function, and energy transfer [11].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycles

| Characteristic | Nitrogen Cycle | Phosphorus Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Atmospheric Nâ‚‚ gas | Phosphate rock (non-renewable) |

| Global Reservoirs | Atmosphere, terrestrial systems, oceans | Geological deposits, soils, aquatic sediments |

| Human Alteration | Haber-Bosch process; fossil fuel combustion | Mining for fertilizers; wastewater discharges |

| Environmental Issues | Eutrophication, algal blooms, GHG emissions | Eutrophication, harmful algal blooms |

| Recovery Potential | From wastewater and agricultural runoff | 15-20% of global fertilizer demand potentially from wastewater [11] |

| Policy Examples | USEPA: 10 mg N Lâ»Â¹ nitrate limit | EU: 0.1 mg P Lâ»Â¹ phosphate limit; China: 0.5 mg P Lâ»Â¹ limit [11] |

Nutrient loss from human activities has severe environmental consequences. Approximately 15 million tons of phosphorus and 21 kg N haâ»Â¹ are lost annually from croplands through leaching, runoff, and erosion [11]. These mobilized nutrients accumulate in aquatic systems, driving eutrophication and harmful algal blooms that degrade water quality and ecosystem health [10] [11]. The economic impacts are substantial, with eutrophication mitigation costs in the U.S. alone estimated at $2.2 billion annually [11].

Trophic Cascades and Biogeochemical Feedback Loops

Conceptual Framework

Trophic cascades—defined as the indirect effects of carnivores on plants mediated by herbivores—represent a powerful mechanism through which biological interactions influence biogeochemical cycles [12] [13]. The "green world" hypothesis first attributed the prevalence of terrestrial vegetation to top-down control of herbivores by predators [13]. These cascading effects can manifest through both consumptive effects (direct predation) and non-consumptive effects (fear-mediated behavioral changes) that alter herbivore feeding patterns [12].

Trophic control of ecosystem structure exists along a continuum from complete bottom-up regulation (driven by nutrient availability and primary productivity) to top-down control (where predators regulate biomass distribution across multiple trophic levels) [13]. Most ecosystems operate under a combination of attenuating top-down and bottom-up control, modulated by nutrient cycling and spatiotemporal variability [13]. The incidence of community-level trophic cascades varies across ecosystems, occurring more frequently in marine benthic ecosystems than in their lacustrine and neritic counterparts, and least often in pelagic ecosystems [13].

Trophic Cascades and Carbon Cycling

Empirical evidence demonstrates that trophic cascades significantly influence carbon dynamics in terrestrial ecosystems. A landmark 13C pulse-chase experiment in grassland ecosystems revealed that predators indirectly enhance carbon fixation and retention through behavioral changes in herbivores, even without reducing herbivore biomass [12].

Table 3: Cascading Effects of Predators on Ecosystem Carbon Dynamics

| Parameter | Plants Only (Control) | Plants + Herbivores | Plants + Herbivores + Carnivores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Plant Biomass | Baseline | No significant difference from control | No significant difference from control |

| 13C Fixation | Baseline | 33% less than control | Mitigated decline, similar to control |

| 13C Respiration | Baseline | 9.3% more fixed C respired | Decreased proportion of fixed C respired |

| Total 13C Storage | Baseline | 1.4-fold less than +carnivore | 1.2-1.4-fold greater than other treatments |

| Belowground Allocation | Baseline | Reduced | Significantly enhanced |

| Grass Carbon Storage | Baseline | Reduced | Greatest storage, creating carbon sink |

This experiment demonstrated that the presence of hunting spiders (Pisaurina mira) indirectly increased carbon retention in plant biomass by 1.4-fold compared to treatments without predators [12]. This effect occurred primarily through non-consumptive mechanisms, as grasshoppers (Melanoplus femurrubrum) reduced feeding time and shifted foraging patterns in response to predation risk [12]. The cascading effects of predators thus began to affect carbon cycling through enhanced carbon fixation by plants, even without initial changes in total plant or herbivore biomass [12].

The diagram below illustrates the pathways through which trophic cascades influence carbon cycling in terrestrial ecosystems:

Pathways of Trophic Cascades on Carbon Cycling

In marine ecosystems, trophic cascades similarly influence carbon sequestration and storage. Predators in kelp forests, coral reefs, and other benthic habitats indirectly enhance carbon storage in vegetation by reducing herbivory pressure [13]. These cascading impacts extend to biodiversity maintenance, extinction prevention, and strong selective pressures that shape organism morphology and behavior across multiple trophic levels [13].

Methodological Approaches

Experimental Designs for Trophic Cascade Studies

Investigating trophic cascades and their biogeochemical consequences requires carefully controlled experimental designs. The established methodology involves replicated field enclosures with factorial manipulation of trophic levels [12]:

Experimental Treatments: Three core treatments in replicated enclosures: (i) plants only (control for animal effects), (ii) plants and herbivores (+ herbivore), and (iii) plants, herbivores, and carnivores (+ carnivore) [12].

Organism Selection: Use dominant species from the study ecosystem, maintaining natural field densities. The grassland experiment used grasses and perennial herbs, the grasshopper herbivore Melanoplus femurrubrum, and the hunting spider carnivore Pisaurina mira [12].

Carbon Tracing: Employ 13C pulse-chase labeling to track carbon fixation, allocation, and respiration dynamics across treatments [12].

Measurement Parameters: Quantify plant community biomass, 13C fixation rates, ecosystem respiration of 13C, belowground vs. aboveground carbon allocation, and carbon storage in different plant functional groups [12].

The experimental workflow for trophic cascade studies is systematized as follows:

Experimental Workflow for Trophic Cascade Studies

Quantitative Approaches for Biogeochemical Cycling

Process-based quantitative descriptions of biogeochemical cycles require integrated measurement strategies. Research on reclaimed water intake areas demonstrates comprehensive approaches to carbon budget quantification [14]:

Conceptual Model Development: Establish a biogeochemical mass balance model with the water body as the core, creating budget links with atmosphere (water-atmosphere), phytoplankton (water-phytoplankton), and fluvial sediment (water-sediment) [14].

Field Measurements: Monitor environmental parameters including pH, turbidity, suspended solids, oxidation-reduction potential, electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids, and dissolved COâ‚‚ along flow gradients [14].

Process Quantification: Calculate internal carbon conversion rates including total organic carbon, dissolved inorganic carbon (COâ‚‚(aq), HCO₃â», CO₃²â»), and precipitation rates of Ca²⺠and Mg²⺠[14].

Incubation Experiments: Investigate sediment role in carbon cycling through laboratory incubation studies measuring organic matter mineralization and dissolved inorganic carbon production [14].

Research Tools and Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Biogeochemical Studies

| Reagent/Technique | Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| 13C Isotope Labeling | Carbon tracing experiments | Pulse-chase methodology to track carbon fixation, allocation, and respiration dynamics [12] |

| Gas Chromatography | Greenhouse gas flux measurements | Quantify COâ‚‚ and CHâ‚„ fluxes at ecosystem interfaces (e.g., water-air) [14] |

| Elemental Analyzer | Total organic carbon (TOC) analysis | Measure organic carbon content in water, soil, and sediment samples [14] |

| Spectrophotometric Kits | Nutrient concentration analysis | Determine nitrate, ammonium, and phosphate concentrations in water samples [11] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Microbial community analysis | Identify and quantify functional genes involved in nutrient cycling (e.g., nifH, amoA, ppk) [11] |

| pH/Ion-Selective Electrodes | Water chemistry characterization | Monitor physicochemical parameters (pH, Eh, EC) in aquatic systems [14] |

| Sediment Traps | Carbon sedimentation quantification | Collect and measure particulate organic matter settling in aquatic ecosystems [14] |

| Climate-Controlled Chambers | Incubation experiments | Study temperature-dependent biogeochemical processes under controlled conditions [11] |

Biogeochemical cycles form the fundamental infrastructure for ecosystem nutrient flow, with trophic cascades serving as critical biological mechanisms that regulate carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus pathways. The integration of top-down trophic control with bottom-up biogeochemical processes creates complex feedback loops that determine ecosystem productivity, carbon sequestration potential, and nutrient retention capacity.

Understanding these interconnected dynamics has never been more urgent, as human activities dramatically alter natural element cycles through fossil fuel combustion, agricultural intensification, and wastewater discharge. The experimental approaches and methodological frameworks outlined herein provide researchers with robust tools to quantify these complex interactions across diverse ecosystems.

Future research priorities should include: (1) scaling trophic cascade-biogeochemical relationships from plot to ecosystem levels, (2) investigating interactive effects of multiple element cycles under global change scenarios, and (3) developing integrated models that couple trophic dynamics with biogeochemical processes to predict ecosystem responses to anthropogenic pressures. Such advances will be essential for developing effective conservation strategies and climate change mitigation approaches that harness natural ecosystem processes.

Predators are not merely passive occupants of the top echelons of food webs; they are dynamic regulators of ecosystem processes whose influence permeates through trophic levels to directly affect biogeochemical cycling [15]. This interconnection forms a critical component of a broader thesis on trophic cascades and biogeochemical feedback loops, representing a paradigm shift from viewing nutrient cycles as solely physically or microbially driven processes. Contemporary research reveals that predators influence elemental transfer and recycling through a complex interplay of consumptive effects (direct killing and consumption of prey) and non-consumptive effects (risk-induced changes in prey traits and behavior) [15] [16]. These effects can alter the distribution of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) among trophic compartments, modify the chemical composition of organic matter, and ultimately determine the fate of nutrients within ecosystems. This technical guide synthesizes the mechanisms, evidence, and methodologies for studying how predators shape nutrient cycling, providing a foundation for researchers investigating the intersection of food web ecology and biogeochemistry.

Theoretical Framework and Key Mechanisms

The theoretical underpinning of predator-driven nutrient cycling rests on integrating principles from ecological stoichiometry with classic ecosystem compartment models [15]. This fusion provides a predictive framework for understanding how predators alter the flow and balance of essential elements.

Core Conceptual Model

At its foundation, the ecosystem is represented as interconnected compartments (soil elemental pools, plants, herbivores, predators) through which elements like C and N flux via trophic interactions, respiration, excretion, egestion, and leaching [15]. This model obeys fundamental mass balance requirements, ensuring elemental inputs equal outputs plus storage at equilibrium. Predators instigate effects through two primary pathways:

- Consumptive Effects (CEs): The killing and consumption of prey determines the flux rate of elements from herbivores to predators. This governs the amount of elements stored in the predator trophic level and released back to the environment via respiration, excretion, and egestion [15].

- Non-Consumptive Effects (NCEs) / Trait-Mediated Effects: The perceived risk of predation alters herbivore behavior (e.g., foraging time and location) and physiology (e.g., metabolic stress) [15] [16]. This changes the flux rate of elements into the herbivore trophic level and can alter the elemental composition of herbivore tissues and waste products.

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways and elemental fluxes in a predator-driven ecosystem model, highlighting the distinct routes of consumptive and non-consumptive effects.

Stoichiometric Bottlenecks and Predator Effects

A critical concept from ecological stoichiometry is the mismatch in elemental demand between trophic levels [15]. Herbivores require a diet with a low C:N ratio to support growth, but often forage on plant material with a high C:N ratio. This creates a bottleneck in the transfer of elements up the food chain. Predators directly and indirectly manipulate this bottleneck:

- Consumptive Effects on Stoichiometry: By reducing herbivore density, predators decrease overall grazing pressure, potentially shifting the plant community toward more palatable species with lower C:N ratios.

- Non-Consumptive Effects on Stoichiometry: Predation risk induces chronic stress in herbivores, elevating their metabolic rate and increasing demand for energy-rich carbon [15]. This can force herbivores to selectively forage for high-carbohydrate foods, leading to excess nitrogen intake which is then excreted [15]. This mechanism represents a direct top-down alteration of nutrient cycling, where fear shifts the balance of C and N entering the soil pool.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Predator Effect Mechanisms on Nutrient Cycling

| Mechanism | Primary Effect on Prey | Impact on Elemental Fluxes | Result on Ecosystem Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumptive (Density-Mediated) | Reduces herbivore population density | Decreases C & N transfer to predator level; increases detritus from killed prey | Alters top-down control on plants; shifts nutrient recycling pathways |

| Non-Consumptive (Trait-Mediated) - Behavioral | Alters herbivore foraging time and habitat use | Reduces herbivory rate, modifying C flow from plants | Can increase plant biomass and C sequestration; spatial heterogeneity in grazing |

| Non-Consumptive (Trait-Mediated) - Physiological | Increases herbivore metabolic stress | Increases herbivore C respiration and N excretion rates | Changes stoichiometry of recycled nutrients (higher N availability); alters soil microbial activity |

Empirical Evidence and Ecosystem Manifestations

The theoretical mechanisms of predator-driven nutrient cycling are supported by empirical evidence from diverse ecosystems. The strength and manifestation of these effects depend on food web structure, predator identity, and environmental context.

Classic Trophic Cascades in Aquatic Systems

Some of the most definitive evidence for predator-driven nutrient cycling comes from aquatic systems, which often have simpler food webs that strongly transmit top-down effects [2].

- Kelp Forest Ecosystems: The sea otter-urchin-kelp trophic cascade is a seminal example. Where sea otters (Enhydra lutris) are present, they suppress sea urchin populations, which allows kelp forests to flourish [2]. The kelp beds then act as significant carbon sinks and their physical structure alters local nutrient dynamics and biodiversity. In areas where otters have been extirpated, urchin populations explode and create "urchin barrens," fundamentally shifting the ecosystem to a state of reduced primary production and altered nutrient cycling [2].

- Lake Ecosystems: Experimental and observational studies have demonstrated that piscivorous fish can control planktivorous fish populations, which in turn releases herbivorous zooplankton from predation. The resulting increase in zooplankton biomass intensifies grazing pressure on phytoplankton, increasing water clarity and altering the cycling of nitrogen and phosphorus [2] [17].

Terrestrial Ecosystems and Behavioral Cascades

The influence of predators on nutrient cycling in terrestrial systems is often mediated through more complex, behaviorally-driven pathways.

- Yellowstone Wolf Reintroduction: The reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in Yellowstone National Park is proposed to have initiated a behaviorally-mediated trophic cascade [2]. Elk (Cervus elaphus) alter their foraging patterns in response to predation risk, avoiding high-risk areas like river valleys. This spatial shift in herbivory has been linked to the recovery of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and willows, which in turn can stabilize stream banks, alter hydrology, and influence soil chemistry through increased litter input [2].

- Transgenerational Amplification of Effects: Recent research reveals that predator effects can amplify across prey generations. A three-year common garden experiment in a terrestrial old-field system demonstrated that the ecosystem impacts of predators on plant community biomass and soil carbon accumulation were larger in the second generation of predator exposure [16]. This amplification was correlated with heightened antipredator behaviors in the second generation, demonstrating a transgenerational plastic response that links eco-evolutionary dynamics to ecosystem function [16].

Table 2: Ecosystem-Level Outcomes of Predator-Driven Nutrient Cycling

| Ecosystem Type | Key Predator | Documented Effect on Nutrient Cycling | Cascade Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kelp Forest (Marine) | Sea Otter | Increases kelp-derived carbon storage & nitrogen retention; alters detrital pathways | Strong |

| Lake (Freshwater) | Piscivorous Fish | Reduces phytoplankton biomass; alters N:P ratios; increases light penetration | Strong |

| Temperate Forest (Terrestrial) | Gray Wolf | Spatial redistribution of herbivory; increases riparian plant litter input & soil C | Moderate to Strong |

| Old-Field (Terrestrial) | Spider/Insect | Increases soil C accumulation; alters N mineralization via prey stress & excretion | Moderate (Amplifies over generations) |

Methodologies for Experimental Investigation

Quantifying the mechanisms of predator-driven nutrient cycling requires integrated experimental approaches that disentangle consumptive and non-consumptive effects.

Experimental Protocols

Researchers employ a combination of field manipulations, mesocosm studies, and controlled laboratory experiments to isolate the pathways through which predators influence biogeochemistry.

Protocol 1: Field-Based Predator Exclusion/Enclosure

- Objective: To measure the in-situ ecosystem-level effects of predator presence/absence on nutrient pools and fluxes.

- Procedure:

- Establish replicate experimental plots in the field of interest.

- Randomly assign plots to treatments: (a) Predator Access, (b) Predator Exclusion (using fences, cages, or other barriers that permit herbivore but not predator access), and (c) Cage Control (to account for artifact effects of the exclusion structure).

- Monitor predator and herbivore activity via camera traps, direct observation, or track counts.

- Periodically collect data on:

- Plant Biomass and Community Composition: Non-destructive measurements and destructive harvests.

- Herbivore Behavior: Foraging time, vigilance, and habitat use.

- Soil and Water Nutrients: Collect soil cores/water samples for analysis of inorganic N (NHâ‚„âº, NO₃â»), available P, and dissolved organic carbon.

- Elemental Stoichiometry: Analyze C:N:P ratios of plant tissue, herbivore frass, and soil.

- Use isotopic tracers (e.g., ¹âµN) to track the flow of nutrients from plants through the food web and into the soil.

Protocol 2: Trait-Mediated Effect Mesocosm

- Objective: To isolate the non-consumptive (risk) effects of predators from their consumptive effects.

- Procedure:

- Construct controlled mesocosms (e.g., terrariums, aquatic tanks) containing a standardized soil medium, plant community, and herbivore population.

- Assign mesocosms to one of three treatments:

- Risk Treatment: Predators are present but physically separated (e.g., in a cage) so they can be seen, smelled, or heard by herbivores but cannot consume them.

- Consumptive Treatment: Free-ranging predators and herbivores.

- Control Treatment: No predators present.

- Maintain experiments for a duration sufficient for physiological and behavioral responses to manifest (weeks to months).

- Measure herbivore physiological stress indicators (e.g., corticosterone levels, metabolic rate), behavioral changes, and elemental excretion rates.

- Quantify endpoints as in Protocol 1, focusing on differences between Risk and Control treatments to isolate the non-consumptive effect.

Protocol 3: Transgenerational Response Experiment

- Objective: To test for the amplification or dampening of predator effects across herbivore generations [16].

- Procedure:

- Establish a laboratory population of the target herbivore.

- Subject the F0 generation to either a predator risk environment or a control environment.

- Collect offspring (F1 generation) and rear them in a common garden environment without predators.

- Divide the F1 generation, subjecting half to the same risk treatment as their parents and half to a control.

- Compare the behavioral, physiological, and ecosystem responses (e.g., plant consumption, soil C accumulation) of the F1 groups to each other and to the F0 generation. An amplified effect is indicated if the F1 risk group shows a stronger response than the F0 risk group [16].

The workflow for a comprehensive investigation integrating these protocols is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Investigating Predator-Nutrient Cycling Links

| Item/Category | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹âµN, ¹³C) | To track the pathway, fate, and transformation of nutrients in the ecosystem. | Pulse-labeling plants with ¹³COâ‚‚ to trace C fixed by photosynthesis into herbivore tissues, predator tissues, and soil organic matter. |

| Respiration Chambers | To measure metabolic COâ‚‚ flux from soil, plants, or individual consumers. | Quantifying elevated respiration rates in herbivores exposed to predator cues, indicating physiological stress [15]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | To determine the elemental (C, N, P) composition and stoichiometry of biological and soil samples. | Measuring C:N ratios of plant tissue before and after predator introduction to test for shifts in plant quality. |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) Kits | To detect predator or prey presence and diet composition from non-invasive samples. | Monitoring predator distribution in a landscape and analyzing gut contents to confirm trophic links. |

| Soil Nutrient Probes & Kits | For in-situ or lab-based measurement of bioavailable nutrients (NO₃â», NHâ‚„âº, PO₄³â»). | Tracking changes in soil nitrogen availability in predator exclusion plots over time. |

| Radio Telemetry / GPS Trackers | To monitor animal movement and behavior in response to experimental treatments. | Documenting elk avoidance of high-risk habitats in Yellowstone following wolf reintroduction [2]. |

| Enzyme Assay Kits (e.g., for urease, phosphatase) | To quantify microbial activity and nutrient processing rates in soil. | Assessing how predator-induced changes in herbivore excretion alter microbial decomposition dynamics. |

| Ethyl Lauroyl Arginate Hydrochloride | Ethyl Lauroyl Arginate Hydrochloride, CAS:60372-77-2, MF:C20H40N4O3 . ClH, MW:421.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| O-Benzyl Posaconazole-4-hydroxyphenyl-d4 | O-Benzyl Posaconazole-4-hydroxyphenyl-d4, CAS:170985-86-1, MF:C44H48F2N8O4, MW:790.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The interconnection between predators and nutrient cycling is a robust ecological phenomenon mediated by both the killing of prey and the pervasive "landscape of fear" that alters prey traits and behavior. These effects propagate through ecosystems to determine the distribution, balance, and recycling rates of key elements like carbon and nitrogen, creating biogeochemical feedback loops that are integral to ecosystem functioning [15]. The growing evidence for transgenerational amplification of these effects [16] further deepens the complexity, suggesting that eco-evolutionary dynamics can intensify the ecosystem-level impacts of predators over time. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is not merely an academic exercise; it is critical for predicting the ecosystem consequences of predator extirpation, for informing rewilding and conservation efforts, and for building resilient ecosystems in an era of global change. Future research must continue to integrate stoichiometric theory, sophisticated experimental designs, and modern tracking technologies to fully unravel the intricate ways in which predators shape the very chemical foundation of their environments.

The 'Landscape of Fear' (LOF) conceptual framework represents a paradigm shift in predator-prey ecology, emphasizing that predators influence their prey not merely through direct consumption, but profoundly through non-lethal, trait-mediated interactions. The concept, formally introduced by Laundré in 2001, is a progeny of the broader "ecology of fear" framework, which defines fear as the strategic manifestation of the cost-benefit analysis of food and safety tradeoffs [18]. Essentially, the LOF is the spatially explicit distribution of perceived predation risk as seen by a population [18]. It is a behavioral trait that provides a spatially dependent measure of how an animal perceives its world (umwelt), influencing where it chooses to forage, rest, and travel based on the perceived threat of predation [18].

This framework is crucial for understanding trait-mediated indirect interactions, where predators trigger changes in prey traits (such as behavior, physiology, or morphology), which in turn indirectly affect other species in the community, including the prey's own resources [19]. These interactions are now recognized as widespread and strong, often carrying equal or greater ecological impact than the direct consumptive effects of predators [20]. The LOF model asserts that the behavior of prey is shaped by psychological maps of their geographical surroundings, which account for the spatial variation in predation risk [21]. This perception of risk drives antipredator behavior, which carries substantial costs by reducing fecundity, survival, and population sizes, thereby becoming a key driver of ecosystem structure and function [21].

Core Principles and Ecological Mechanisms

The Theoretical Foundation: From Risk Perception to Ecosystem Impact

The operation of the Landscape of Fear can be conceptualized as a sequence of distinct, measurable spatial maps. The central element is the Landscape of Fear itself, defined as the spatial variation in prey perception of predation risk [22]. This cognitive map is distinct from, though influenced by, three other interconnected landscapes:

- The Physical Landscape: The abiotic and biotic template, including topography, vegetation structure, and resource distribution.

- The Predation Risk Landscape: The spatial variation in the actual likelihood of encounter and death by a predator.

- The Prey Response Landscape: The observable spatial manifestation of antipredator behavior, such as habitat use, foraging patterns, and vigilance [22].

The following diagram illustrates the relationships and potential mismatches between these landscapes:

Figure 1: The Core Conceptual Framework of the Landscape of Fear. The model centers the Landscape of Fear (prey perception) as distinct from the actual risk and the physical environment, while also illustrating the feedback loop where prey responses can alter the physical landscape through trophic cascades [22].

Key Factors Shaping the Landscape of Fear

The topography of an individual's LOF is sculpted by a complex interplay of internal and external factors, which guide the strategic trade-off between foraging benefits and predation costs.

Predation Risk Factors: The most studied factor is direct and perceived predation risk, which is influenced by (1) the diversity of the predator community, (2) predator activity levels (predation intensity), and (3) the information available to the prey about the likelihood of an attack [18]. For instance, the "rugosity" or "wrinkled" nature of the LOF increases with predator activity, meaning the difference in risk between safe and risky patches becomes steeper [18].

Prey Energetic-State: An animal's internal state critically modulates its risk-taking behavior. Prey in a poor energetic state, due to resource shortage, drought, or disease, are often forced to take greater risks to meet their physiological needs [18]. This aligns with the asset protection principle, where an animal in a high energy state has more to lose and should be more risk-averse [22].

Demographics and Competition: Life-history stages and intraspecific competition alter risk perception. For example, parents protecting offspring may exhibit heightened aversion to risk [18], while competition for mates can temporarily increase risk-taking in males [18]. Furthermore, intra-specific competition can force subordinate individuals into riskier habitats [18].

Prey Ontogeny: The relative strength of consumptive and non-consumptive effects can decouple as prey grow. A study on the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus found that consumptive effects were greater on smaller urchins, while non-consumptive effects (reduced grazing) acted only on larger, predation-resistant individuals [23]. This finding that "risk and fear" change with ontogeny is crucial for predicting community impacts.

Methodologies for Quantifying the Landscape of Fear

Experimental Protocols and Field Methods

Empirically measuring the LOF requires innovative experimental designs that manipulate either predation risk, resource distribution, or both, while controlling for confounding variables. The following protocols are central to the field.

Protocol 1: Giving-Up Density (GUD) Experiments This method quantifies foraging cost and perceived predation risk by measuring the amount of food left behind in a patch [18].

- Setup: Multiple foraging trays are established across a landscape, containing a known amount of food mixed with a neutral, inedible substrate (e.g., sand).

- Manipulation: Tray placement systematically varies environmental covariates such as distance to cover, vegetation height, or illumination.

- Monitoring: After a standardized foraging period, the remaining food is collected and weighed. This residual is the Giving-Up Density.

- Analysis: Lower GUDs indicate a higher perceived harvest rate and thus a lower perceived predation risk. Spatial analysis of GUDs maps the LOF, revealing how factors like distance to cover shape risk perception [18].

Protocol 2: Landscape-Scale Habitat Manipulation (as in Bardia National Park) This protocol tests the integration of the LOF concept into active wildlife management by manipulating both resources and perceived safety [24].

- Design: Establish a series of experimental plots that vary in:

- Size: To test for the "safe site" effect (e.g., 49 m², 400 m², 3600 m²).

- Mowing Frequency: To alter resource quality and visibility (e.g., 0 to 4 times per year).

- Fertilization: To enhance resource quality (e.g., none, phosphorus, nitrogen).

- Measurement: Use indirect metrics like pellet group counts to measure habitat use by herbivores (e.g., chital, swamp deer, hog deer).

- Spatial Analysis: Compare use between plot centers and edges to determine if animals perceive the core of large, open plots as safer, despite the energetic cost of traveling further from cover [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

A range of methodological tools and "reagents" are essential for implementing these protocols and advancing LOF research.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Landscape of Fear Studies

| Item/Category | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GPS Telemetry Collars | Track fine-scale movement and habitat selection of prey and predators in relation to spatial features. Used to construct response landscapes and validate risk models [22]. | Studying elk movement in response to wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone [18]. |

| Giving-Up Density (GUD) Stations | Quantify perceived predation risk by measuring foraging cost. The primary tool for mapping the rugosity of the LOF [18]. | Foraging trays for desert gerbils used to measure risk from owls vs. vipers [18]. |

| Camera Traps & Drones | Remotely monitor animal presence, behavior (vigilance), and habitat use without human interference. Validate pellet count data [24]. | Monitoring deer use of experimental plots in Bardia National Park [24]. |

| Predator Cues | Experimentally simulate predation risk to isolate non-consumptive effects from consumptive ones. | Using audio playbacks of predator calls, artificial predator scents (e.g., wolf urine), or model predators [23]. |

| GIS & Spatial Statistics Software | Analyze and visualize the spatial relationships between risk factors, prey perception, and behavioral responses. Create predictive models of the LOF [22]. | Mapping predation risk models derived from landscape features against prey GPS data. |

| 5'-DMT-5-F-2'-dU Phosphoramidite | FdU-amidite|5-F-dU CE Phosphoramidite Reagent | FdU-amidite for incorporating 5-fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine into oligonucleotides. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 1-Cbz-3-Hydroxyazetidine | 1-Cbz-3-Hydroxyazetidine, CAS:128117-22-6, MF:C11H13NO3, MW:207.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Trophic Cascades and Biogeochemical Loops

The LOF concept provides the mechanistic link that explains trait-mediated trophic cascades and their subsequent biogeochemical feedbacks. When prey alter their habitat use and foraging behavior in response to fear, they can indirectly shape the distribution, biomass, and species composition of basal resources like plants, thereby influencing ecosystem-level processes.

A canonical example is the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone National Park. The presence of wolves created a LOF for elk, which reduced their browsing intensity in high-risk areas like river valleys. This behavioral shift, a trait-mediated interaction, facilitated the regrowth of aspen and willows, a trophic cascade [21]. This vegetation recovery then led to further biogeochemical feedbacks, including streambank stabilization and altered nutrient cycling [18] [21]. The following diagram outlines this causal pathway and its ecosystem consequences:

Figure 2: Pathway of a Trait-Mediated Trophic Cascade. The diagram illustrates how a predator, via the Landscape of Fear, triggers behavioral changes in prey that cascade down to affect primary producers and ultimately drive biogeochemical feedbacks, as observed in Yellowstone National Park [18] [21].

The flexibility in trait expression is a key source of context-dependency in ecosystem functioning [19]. For instance, the competitive goldenrod Solidago rugosa dominates old-field ecosystems not only through resource competition but also because its structure serves as a predation refuge for grasshopper herbivores, which in turn determines grazing pressure and nutrient cycling [19]. This demonstrates that functional traits affecting ecosystems cannot be understood in isolation from the trait-mediated interactions driven by the LOF.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from major Landscape of Fear studies, highlighting the measurable effects of perceived risk on prey behavior and ecosystem properties.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Findings in Landscape of Fear Research

| Study System / Organism | Experimental Manipulation | Key Measured Outcome | Result & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bardia National Park, Nepal (Cervids) [24] | Plot size (49m², 400m², 3600m²) & mowing/fertilization. | Pellet group density (use/m²). | Larger plots had higher use (0.10/m² in 3600m² vs 0.05/m² in 49m²). Core areas of large plots preferred (0.21/m² center vs 0.13/m² edge), indicating perceived safety in large, open areas. |

| Negev Desert Gerbils [18] | Exposure to different predator types (Barn Owls vs. Vipers) in a vivarium. | Giving-Up Density (GUD) and foraging effort. | Gerbils altered their LOF more significantly in response to the higher perceived threat (owls), demonstrating risk assessment is predator-specific. |

| Mediterranean Sea Urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) [23] | Exposure to predator cues. | Grazing activity on macroalgae. | Non-consumptive effects reduced grazing by 60% in larger, predation-resistant urchins, showing decoupling of risk and fear with ontogeny. |

| Song Sparrows (Melospiza melodia) [18] | Playback of predator calls to simulate risk. | Reproductive output (number of offspring). | "Parental intimidation" by predators led to a 40% reduction in offspring production, linking fear directly to demography. |

Table 3: Factors Modulating the Topography of the Landscape of Fear

| Modulating Factor | Effect on Risk Perception (LOF 'Rugosity') | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Prey Ontogeny | Changes dynamically with life stage; larger prey may feel safer from consumption but not from fear effects. | Larger sea urchins ignored predator cues, but their grazing was significantly suppressed by them [23]. |

| Prey Energetic-State | Increases risk-taking and flattens the LOF when prey are in a poor state (e.g., hungry, thirsty). | Ungulates in drought forage near crocodile-infested waterholes, prioritizing water over safety [18]. |

| Predator Hunting Mode | Ambush predators create sharp risk gradients near cover; cursorial predators create risk in open areas. | Gerbils showed different spatial avoidance behaviors to ambush vipers versus flying owls [18]. |

| Human Presence | Can create a "super predator" effect, inducing a fear response that exceeds that of natural predators. | Mesocarnivores like badgers exhibited greater fear of human voices than of dogs or wolves [21]. |

The 'Landscape of Fear' framework has fundamentally refined our understanding of predator-prey interactions by highlighting the pervasive power of non-consumptive, trait-mediated effects. It provides the mechanistic tissue that connects predator presence to prey behavior, community-level trophic cascades, and ecosystem functioning, including biogeochemical cycles. Moving forward, research is being directed towards several key frontiers [18] [22]:

- Applied Management: Using the LOF as a trait to define population habitat-use and suitability to guide conservation actions, such as the deliberate design of safe habitats in managed landscapes [24].

- Temporal Dynamics: Studying the diel and seasonal dynamics of the LOF, acknowledging that it is a fluid and shifting landscape, not a static map.

- Intra-Population Variability: Investigating how the LOF differs between individuals within a population based on personality, state, and experience.

- Neuro-Ecological Integration: Combining ecology and neuroscience to understand the neurological underpinnings and long-term effects of fear in wild animals (e.g., PTSD-like changes) [21].

- Cross-Context Synthesis: Further integration with the concept of "energy landscapes" and a broader application of state- and prediction-based theory (SPT) to model how unique individuals make trade-offs in unpredictable environments [20].

Trophic cascades, the indirect effects of predators propagating through food webs to influence lower trophic levels, represent a fundamental ecological process regulating ecosystem structure and function [17]. These cascades manifest as density-mediated interactions, where predators reduce herbivore populations, and trait-mediated interactions, where predator presence alters herbivore behavior [17]. Understanding the differential strength of these cascades across aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems is critical for predicting ecosystem responses to anthropogenic disturbances and informing conservation strategies. This review synthesizes current knowledge on comparative cascade strength, examining the underlying mechanisms, methodological approaches for quantification, and implications for ecosystem management within the broader context of biogeochemical feedback loops in ecosystems research.

Quantitative Comparison of Cascade Strength

Meta-analyses reveal significant differences in how trophic cascades propagate through aquatic versus terrestrial ecosystems. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics and findings.

Table 1: Comparative strength of trophic cascades in aquatic versus terrestrial ecosystems

| Characteristic | Aquatic Ecosystems | Terrestrial Ecosystems | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cascade Strength | Stronger, more frequently observed | Weaker, more attenuated | [25] [17] |

| Herbivore Response Type | Primarily density-mediated | Mix of density and trait-mediated | [17] |

| Attenuation Pattern | Propagates across multiple trophic levels with less attenuation | Strongly attenuated, often within one trophic level | [25] [17] |

| Key Regulating Factors | Consumer uptake and mortality rates; nutrient stoichiometry | Behavioral interactions; intraguild predation; species richness | [26] [17] |

| Metabolic/Taxonomic Influences | Systems dominated by invertebrate herbivores and endothermic vertebrate predators show strongest cascades | Less clearly defined by metabolic class | [17] |

The log10 response ratio has emerged as a standardized metric for quantifying cascade strength. In a notable terrestrial example, the reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in Yellowstone National Park produced a log10 ratio of 1.21, corresponding to a ∼1500% increase in willow crown volume—a strength surpassing 82% of those reported in a global meta-analysis of trophic cascades [27]. Despite this strong localized effect, terrestrial cascades generally demonstrate greater attenuation than their aquatic counterparts [25].

Mechanisms Underlying Ecosystem Differences

Structural and Functional Attributes

Several hypotheses attempt to explain the divergent cascade strengths between ecosystems. Food chain compartmentalization appears more pronounced in terrestrial systems, creating weak links that inhibit cascade propagation [17]. Additionally, behavioral responses of prey to predators differ significantly between media; trait-mediated indirect interactions (e.g., "fear of being eaten") play a more substantial role in terrestrial environments, potentially creating non-consumptive cascade effects that complement density-mediated interactions [17].

Biogeochemical Influences

Nutrient stoichiometry regulates cascade strength differently across ecosystems. Aquatic systems experience more direct nutrient coupling, where altered nutrient compositions rapidly affect all trophic levels [26]. In aquatic environments, nutrient enrichment (eutrophication) with imbalanced nitrogen:phosphorus ratios creates immediate effects on algal species composition, which subsequently propagate upward through the food web [26]. Consumers further accelerate stoichiometric discrepancies through various feedbacks, release, and recycling pathways [26].

Table 2: Methodological approaches for quantifying trophic cascade strength

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Ecosystem Application | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Observation | Long-term monitoring; predator reintroduction studies; natural experiments | Both aquatic and terrestrial | Population densities; biomass measurements; vegetation structure |

| Experimental Manipulation | Mesocosm experiments; nutrient enrichment; predator exclusion | More common in aquatic systems | Log10 response ratio; change in biomass across trophic levels |

| Mathematical Modeling | Food chain models; network analysis; stability analysis | Theoretical frameworks applied to both | Cascade strength; interaction strength; stability parameters |

| Stoichiometric Analysis | Nutrient ratio measurements; elemental analysis | Particularly informative in aquatic systems | C:N:P ratios; nutrient use efficiency; recycling rates |

Experimental Protocols for Cascade Quantification

Field-Based Assessment Protocol

Terrestrial Cascade Monitoring (Yellowstone Model)

- Site Selection: Identify representative riparian areas with established willow (Salix spp.) communities

- Predator Presence Documentation: Monitor gray wolf (Canis lupus) and other large carnivore populations through direct observation, tracking, and remote cameras

- Herbivore Density Estimation: Conduct regular elk (Cervus canadensis) population surveys using standardized transect or aerial methods

- Vegetation Response Quantification:

- Measure willow height and crown dimensions at permanently marked stations

- Calculate crown volume using geometric modeling (e.g., cylindrical or spherical approximations)

- Conduct annual measurements during peak growing season to minimize seasonal variability

- Compare pre- and post-reintroduction data using the log10 response ratio: LRR = log10(Xpost/Xpre), where X represents crown volume [27]

Aquatic Mesocosm Experiment Protocol

Nutrient-Mediated Cascade Analysis

- Experimental Setup: Establish multiple replicated mesocosms (≥12) with standardized volumes and initial biological communities

- Treatment Application: Implement gradient nutrient additions (N and P at varying ratios) to simulate eutrophication scenarios [26]

- Community Monitoring:

- Quantify phytoplankton biomass via chlorophyll-a measurements and microscopic enumeration

- Sample zooplankton communities using vertical tows and enumeration

- Monitor planktivorous fish populations through mark-recapture or visual survey methods

- Stoichiometric Analysis: Measure elemental composition (C:N:P) of key species and seston across trophic levels [26]

- Statistical Analysis: Use structural equation modeling to quantify direct and indirect pathways of trophic interactions

Visualization of Cascade Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the differential pathways of trophic cascades in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, highlighting key feedback mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for trophic cascade studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Ecosystem Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll-a Extraction Kit | Phytoplankton biomass quantification | Measures primary producer abundance in aquatic systems | Primarily aquatic |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (¹âµN, ¹³C) | Food web tracing | Tracks energy flow and nutrient pathways through trophic levels | Both |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) Sampling Kit | Biodiversity assessment | Detects species presence through genetic material in environment | Both |

| Dendrometer Bands | Tree and shrub growth monitoring | Measures plant response to herbivore pressure | Primarily terrestrial |

| Nutrient Autoanalyzer | Water chemistry analysis | Quantifies N, P, and other nutrient concentrations | Primarily aquatic |

| Radio Telemetry Equipment | Animal movement tracking | Monitors predator-prey spatial interactions and behavior | Both |

| Mesocosm Experimental Systems | Controlled ecosystem studies | Isulates specific trophic interactions for manipulation | Both |

| GIS and Remote Sensing Software | Landscape-scale pattern analysis | Maps vegetation changes and habitat use across large areas | Both |

| 5,5'-Dicarboxy-2,2'-bipyridine | 5,5'-Dicarboxy-2,2'-bipyridine, CAS:1802-30-8, MF:C12H8N2O4, MW:244.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Azocarmine G | Azocarmine G, CAS:25641-18-3, MF:C28H18N3NaO6S2, MW:579.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis of trophic cascade strength across aquatic and terrestrial realms reveals fundamental differences in ecosystem organization and functioning. Aquatic ecosystems generally exhibit stronger cascade propagation with less attenuation across trophic levels, while terrestrial systems demonstrate greater compartmentalization and stronger trait-mediated interactions. These differences emerge from distinct structural constraints, biogeochemical contexts, and behavioral dynamics characteristic of each environment.

Understanding these differential cascade strengths has profound implications for ecosystem management and conservation strategies. The restoration of apex predators, as demonstrated by the Yellowstone wolf reintroduction, can catalyze powerful top-down effects that restore ecosystem structure and function [27] [28]. In aquatic systems, managing nutrient inputs requires consideration of how stoichiometric imbalances propagate through food webs [26]. Future research should focus on integrating molecular tools, advanced monitoring technologies, and cross-ecosystem comparisons to further elucidate the mechanisms governing cascade strength and their implications for ecosystem resilience in an era of rapid global change.

Research and Restoration: Methodologies for Measuring and Applying Trophic Interactions

Understanding trophic linkages—the feeding relationships between species—is fundamental to ecology and crucial for predicting how ecosystems respond to environmental change. These linkages form the architecture of food webs, and their disruption can trigger trophic cascades, which are powerful indirect interactions that can control entire ecosystems [29] [4]. For instance, the removal of a top predator can lead to an overabundance of herbivores, which in turn overgraze vegetation, fundamentally altering the ecosystem structure [4]. These dynamics are intimately connected to biogeochemical feedback loops, as the flow of nutrients and energy through food webs regulates elemental cycling in the biosphere [30].

Modern ecosystem research relies on a suite of advanced technologies to quantify these complex relationships. This guide details three pivotal techniques: stable isotope analysis, which traces the flow of nutrients through food webs; bioacoustics, which monitors species presence and behavior through vocalizations; and acoustic telemetry, which tracks animal movement and interactions. Together, these tools provide the empirical data needed to map trophic interactions, measure the strength of cascades, and model ecosystem-wide responses to perturbations, thereby offering a holistic view of ecosystem function and stability [29] [31] [32].

Stable Isotope Analysis

Core Principles and Ecological Applications

Stable isotope analysis (SIA) leverages the natural variation in the ratios of heavy to light isotopes of elements such as carbon (13C/12C), nitrogen (15N/14N), hydrogen (2H/1H), and oxygen (18O/16O) to unravel ecological processes. These ratios, expressed as δ-values (e.g., δ13C, δ15N), act as natural recorders or fingerprints [31]. The fundamental principle is that isotopic compositions are altered, or fractionated, through biological, geochemical, and physical processes, creating distinctive signatures in organic matter [33].

In trophic ecology, SIA is indispensable for:

- Trophic Position Estimation: Nitrogen isotope ratios (δ15N) exhibit a predictable enrichment (typically 3-4‰) with each trophic transfer, allowing researchers to estimate an organism's trophic level [31] [33].

- Nutrient Source Tracing: Carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) change minimally with trophic transfer but vary significantly among primary producers with different photosynthetic pathways (e.g., C3 vs. C4 plants, phytoplankton vs. benthic algae). This makes δ13C an excellent tracer of basal nutrient sources within a food web [31] [33].