Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: Diffusion-Based Cultivation for Novel Marine Bacteria and Drug Discovery

Over 99% of marine bacteria remain uncultured, representing a vast untapped reservoir of biodiversity and biotechnological potential.

Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: Diffusion-Based Cultivation for Novel Marine Bacteria and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Over 99% of marine bacteria remain uncultured, representing a vast untapped reservoir of biodiversity and biotechnological potential. This article explores diffusion-based cultivation methods, innovative techniques designed to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches by mimicking natural habitats. We detail the principles and apparatuses, such as the 'microbial aquarium,' that enable the growth of previously unculturable taxa. The discussion covers optimization strategies, comparative performance analyses against conventional methods, and the profound implications for discovering novel natural products and therapeutic agents, providing a critical resource for microbiologists and drug development professionals.

The Uncultured Majority: Why Traditional Methods Fail and The Promise of Diffusion

The term Microbial Dark Matter (MDM) describes the immense majority of microbial organisms, primarily bacteria and archaea, that microbiologists are unable to culture in the laboratory using standard methods due to an inability to replicate their required growth conditions [1]. In marine ecosystems, these uncultured microorganisms represent a vast, unexplored reservoir of biological diversity and metabolic potential. It is estimated that over 99% of marine microorganisms have not been cultivated, confining their study almost entirely to culture-independent, genomic-based techniques [2]. This knowledge gap is profound; despite their numerical dominance and critical roles in global biogeochemical cycles, the basic biology, physiology, and ecological interactions of most marine microbes remain shrouded in mystery.

The challenge is analogous to astronomy's dark matter problem: just as astronomers infer the existence of unseen mass through its gravitational effects, microbiologists infer the presence and function of MDM through molecular signals and metagenomic sequencing [1]. However, a key distinction exists. Unlike cosmological dark matter, microbial dark matter is directly accessible; we can sequence its genes, observe cells under microscopes, and, with innovative approaches, increasingly bring it into cultivation [3]. This Application Note defines the scale of the MDM problem within marine environments and details advanced diffusion-based protocols designed to illuminate this biological frontier, providing researchers with actionable methodologies to bridge the great cultivation divide.

Quantifying Marine Microbial Dark Matter

The Great Plate Count Anomaly in the Ocean

The discrepancy between the number of microbial cells observed under a microscope and the number of colonies that grow on standard culture media is known as the "great plate count anomaly." This anomaly is particularly extreme in marine settings. Marine ecosystems are teeming with life, with microbial abundances estimated at 10^4–10^7 cells/mL in seawater and a staggering 10^3–10^10 cells/cm^3 in sediments [4] [2]. These microbes, including bacteria, archaea, and protists, constitute over 70% of the total marine biomass and are the fundamental drivers of the ocean's biogeochemical cycles [5].

Traditional cultivation methods with defined, nutrient-rich media, such as marine agar 2216, have historically only been able to isolate a minute fraction of this diversity. This has resulted in a situation where entire microbial phyla are known only from environmental DNA sequences, with no laboratory-cultivated representatives available for study [1]. For example, the Omnitrophota (formerly candidate phylum OP3) were first detected via DNA sequencing nearly three decades ago and are frequently found in aquatic samples worldwide, yet have only recently been characterized in detail without successful pure cultivation [6].

Genomic Insights into Diversity and Novelty

The advent of high-throughput sequencing has allowed scientists to quantify the scale of MDM more precisely. Metagenomic studies suggest that the total diversity of marine microbes could be as high as one trillion species, though this estimate is still debated [5]. Single-cell genomics and metagenomics have uncovered numerous new branches on the tree of life, revealing that a single study can recover hundreds of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from an environment, a significant proportion of which represent novel, uncultured lineages.

Table 1: Novel Microbial Lineages Recovered from Recent Marine Studies

| Environment/Source | Total Genomes/Isolates Recovered | Classified as Novel MDM | Key Novel Lineages Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypersaline Microbial Mats (Solar Lake) [7] | 364 MAGs | 116 MAGs (~30%) | Ca. Lokiarchaeota, Ca. Heimdallarchaeota, Ca. Coatesbacteria (RBG-13-66-14), novel Myxococcota |

| Marine Sediments (Diffusion-Based Cultivation Approach) [4] | 196 Isolates | 115 Isolates (58% novelty ratio) | Verrucomicrobiota, Balneolota |

| Marine Sediments (Traditional Cultivation) [4] | 165 Isolates | 20 Isolates (12% novelty ratio) | Predominantly novel species within known phyla |

These data underscore two critical points: first, culture-independent methods reveal a vast phylogenetic novelty, with some ecosystems having nearly a third of their recovered genomes belonging to MDM [7]. Second, innovative cultivation methods can dramatically increase the yield of novel isolates from the same environment compared to traditional techniques, successfully accessing phyla like Verrucomicrobiota that are rarely, if ever, captured by standard media [4].

Advanced Protocol: Diffusion-Based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA)

The following protocol, the Diffusion-Based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA), is designed to overcome the key limitations of traditional methods by using a device that allows for chemical exchange with the natural environment and low-nutrient media that mimic native conditions [4] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for the DICA Protocol

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Microbial Aquarium Apparatus | A custom glass device consisting of a large outer chamber and smaller, semi-permeable inner chambers that allow for diffusion of chemicals and signaling molecules. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filter (0.22 µm pore size) | Creates a semi-permeable barrier on inner chambers, permitting molecular exchange while preventing cell migration. |

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) | A defined salt mixture that serves as the base for all media, replicating the ionic composition of seawater. |

| Low-Nutrient Media (Lig & St) | Growth media supplemented with complex/recalcitrant carbon sources (0.5% alkali-lignin or 0.5% starch) to simulate natural organic matter. |

| Sediment Slurry (0.5% w/v) | A dilute suspension of the environmental sample used to fill the outer chamber, recreating the native chemical and biological context. |

| Trace Element & Vitamin Mixtures | Supplements to provide essential micronutrients required by fastidious microorganisms. |

| Diluted Marine 2216E & R2A Agar (50%) | Low-nutrient solid media used for the subsequent sub-cultivation of enriched microbes. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Methodology

Part A: Preparation of the Microbial Aquarium

- Apparatus Sterilization: Thoroughly clean the custom glass "microbial aquarium." Sterilize the entire apparatus by treating with 75% (v/v) ethanol, rinsing with particle-free molecular grade water, and then drying under UV light in a laminar flow hood for a minimum of 12 hours [4].

- Inner Chamber Preparation: The microbial aquarium consists of a large outer glass box (e.g., 30 L) and three inner cylindrical glass chambers (e.g., 2 L each). Drill 15 holes (6 mm diameter) evenly across the surface of each inner chamber. Securely attach a 0.22 µm polycarbonate membrane filter over the holes using a non-toxic, waterproof glue, ensuring a complete seal. This membrane is critical as it enables the diffusion of metabolites, nutrients, and signaling molecules while keeping the microbial cells separate [4] [8].

- Media Formulation: Prepare the following three types of low-nutrient media in artificial seawater (ASW) [4]:

- Lig-medium: Supplement ASW with 0.5% (w/v) alkali-lignin.

- St-medium: Supplement ASW with 0.5% (w/v) starch.

- ASW-medium: Artificial seawater only, with no additional carbon source.

- Apparatus Inoculation:

- Place the prepared inner chambers inside the sterilized outer container.

- In the outer chamber, add 75 g of fresh marine sediment mixed with 15 L of ASW to create a 0.5% (w/v) sediment slurry. This slurry recreates the natural chemical environment.

- To each of the three inner chambers, add 0.25 g of the same sediment along with 500 mL of one of the three prepared media (Lig-, St-, and ASW-medium). Use a different medium in each inner chamber to maximize the diversity of organisms targeted.

- Seal the inner chambers with glass lids and cover the outer chamber with a glass sheet.

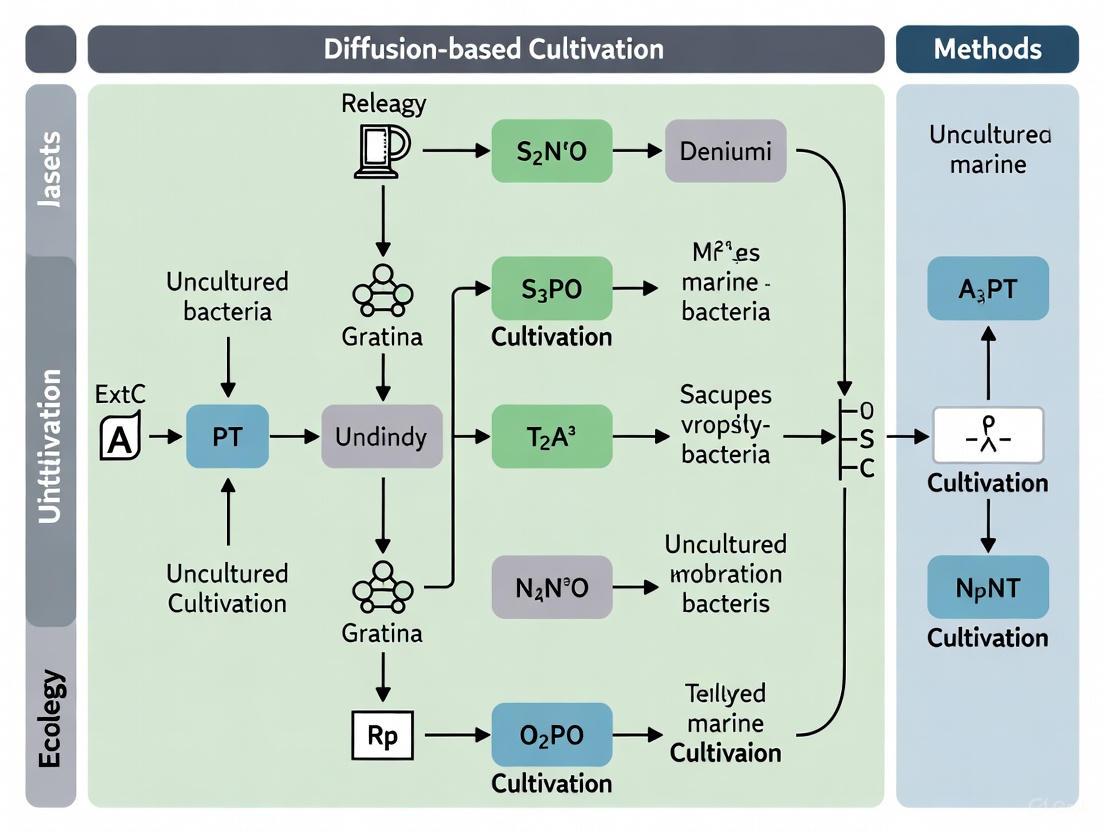

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and structure of the DICA system:

Part B: Incubation and Monitoring

- Incubation Conditions: Place the entire assembled system in a temperature-controlled environment at 25°C for an extended period of 4 weeks [4]. Longer incubation times are often necessary to support the slow growth of rare and previously uncultured bacteria.

- Homogenization: To ensure consistent chemical diffusion, use an electric rotator to gently stir the contents of the outer chamber. Manually stir the contents of the inner chambers with a sterile pipette at 72-hour intervals.

Part C: Sub-cultivation and Isolation

- Sampling: After the 4-week incubation, aseptically collect samples from the inner chambers.

- Plating: Perform serial dilutions of the enriched culture and spread onto solid agar plates prepared with 50% diluted marine 2216E or R2A media. These diluted solid media maintain the low-nutrient conditions favorable for MDM.

- Colony Selection: Incubate plates and monitor for colony formation. Select colonies based on varying morphologies for further purification.

- Identification: Purify isolates through repeated streaking. Identify and assess novelty by performing 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Discussion: Implications for Research and Drug Discovery

Successfully cultivating marine MDM using the DICA protocol or similar methods opens new frontiers in microbial ecology and biotechnology. The isolates obtained are not merely taxonomic curiosities; they represent sources of novel bioactive compounds, enzymes with unique properties for industrial applications, and foundational biological knowledge [2]. For drug development professionals, this approach provides access to a untapped reservoir of genetic diversity that may encode novel antibiotics, anti-tumor agents, and other pharmaceuticals [2].

Furthermore, illuminating MDM is critical for accurately modeling global biogeochemical cycles. Studies have shown that microbial community composition and functional potential shift in response to environmental changes like ocean warming [9]. These shifts, which include changes in the genes responsible for organic carbon degradation, nitrogen cycling, and nutrient stress responses, cannot be fully understood without knowing the capabilities of the dominant yet uncultured players [9] [7]. Protocols like DICA, which bridge the gap between in situ environmental conditions and laboratory cultivation, are therefore essential tools for moving from genetic potential to validated function, transforming the microbial dark matter of the oceans from a black box into a catalog of characterized biological resources.

Limitations of Traditional Cultivation Media and Conditions

The vast majority of marine microorganisms, crucial players in global biogeochemical cycles, remain inaccessible to scientific study due to the limitations of traditional cultivation techniques [2]. It is estimated that over 99% of marine bacteria and archaea have not been cultured under standard laboratory conditions, creating a significant gap in our understanding of microbial diversity and function [2] [4]. This "microbial dark matter" represents an unexplored reservoir of genetic and metabolic potential with profound implications for biotechnology, drug discovery, and environmental science [2] [10].

The core challenge stems from an inherent disparity between artificial laboratory environments and the complex, dynamic natural habitats where these microorganisms evolved. Traditional cultivation methods, largely unchanged for over a century, fail to replicate the intricate physical, chemical, and biological conditions essential for the survival and growth of most marine microbes [10] [4]. This application note examines the specific limitations of traditional cultivation approaches and highlights advanced, diffusion-based strategies designed to overcome these barriers, thereby enabling the cultivation of previously uncultured marine bacteria.

The Great Plate Count Anomaly and Its Causes

The discrepancy between microscopic cell counts and colony-forming units in environmental samples, known as the "great plate count anomaly," underscores the fundamental inadequacy of traditional cultivation [11] [12]. While once generalized to suggest that less than 1% of environmental microbes are culturable, recent studies indicate this figure can be higher with improved techniques, yet a vast diversity remains inaccessible [11]. The primary limitations of traditional methods can be categorized as follows:

- Nutritional Inadequacy: Conventional nutrient-rich media (e.g., high in peptone, yeast extract) favor fast-growing copiotrophs but inhibit slow-growing oligotrophs adapted to low nutrient concentrations in many marine environments like open oceans and deep sediments [8] [13]. These media lack the complex recalcitrant organic substrates (e.g., lignin, humic acids) that serve as carbon sources in deep-sea sediments [8] [4].

- Disruption of Microbial InterdVependencies: In nature, microbes exist in complex consortia where metabolic cross-feeding, quorum sensing, and other interactions are vital. Traditional isolation on pure-culture plates severs these dependencies, leaving many microbes unable to grow without metabolites or signaling molecules from their neighbors [2] [10] [14].

- Failure to Mimic Natural Physicochemical Conditions: Laboratory conditions often fail to replicate key environmental parameters such as precise temperature, pressure, pH, and oxygen gradients. This is particularly critical for extremophiles from deep-sea hydrothermal vents or high-pressure zones [5] [10].

- Overlooked Physiological States: Many bacteria enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state under stress. While metabolically active, these cells do not form colonies on conventional media, necessitating specific resuscitation stimuli [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Cultivation Outcomes

The following tables summarize experimental data demonstrating the superior performance of advanced diffusion-based and integrative cultivation methods compared to traditional approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of Traditional vs. Diffusion-Based Cultivation from Marine Sediment

| Cultivation Approach | Total Isolates | Novel Taxa Cultivated | Novelty Ratio | Taxonomic Classes Recovered | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Cultivation Approach (TCA) | 165 | 20 (Species level) | 12% | 6 | Standard nutrient-rich agar plates [8] [4] |

| Diffusion-Based Integrative Approach (DICA) | 196 | 115 (39 at genus level, 4 at family level) | 58% | 12 | "Microbial Aquarium" with low-nutrient media and diffusion chambers [8] [4] |

Table 2: Performance of Other Advanced Cultivation Methods for Marine Microbes

| Method | Key Principle | Application | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spent Culture Medium (SCM) | Uses supernatant from helper archaea (e.g., Ca. Bathyarchaeia) to provide growth factors | Deep-ocean sediment | 35% novelty ratio (80 new strains); isolated rare phyla like Planctomycetota | [15] |

| High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction | Dilution in defined low-nutrient media to isolate oligotrophs | Freshwater lakes (analogous to marine oligotrophs) | Recovered widespread, abundant oligotrophs; up to 72% of genera from original sample | [13] |

| In Situ Cultivation (I-tip) | Device allows chemical exchange with natural environment in situ | Sponge-associated bacteria | Isolated novel species requiring "growth initiation factors" from the host | [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Diffusion-Based Integrative Cultivation

This protocol details the application of the Diffusion-based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA) for isolating previously uncultured bacteria from marine sediments [8] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for DICA

| Item | Specification/Composition | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) | 26.0 g/L NaCl, 5.0 g/L MgCl₂·6H₂O, 1.4 g/L CaCl₂·2H₂O, 4.0 g/L Na₂SO₄, 0.3 g/L NH₄Cl, 0.1 g/L KH₂PO₄, 0.5 g/L KCl, trace elements, vitamins, NaHCO₃. | Base for media, provides essential ions and osmotic balance. |

| Lignin Medium (Lig-medium) | ASW supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) alkali-lignin. | Provides recalcitrant carbon source to target microbes specialized in complex carbon degradation. |

| Starch Medium (St-medium) | ASW supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) starch. | Complex polysaccharide source for enrichment. |

| Low-Nutrient Agar Plates | 50% diluted Marine 2216E or R2A agar with 1.5% agar. | For subsequent sub-cultivation of enriched isolates. |

| Microbial Aquarium Apparatus | Outer glass chamber (30 L), inner semi-permeable chambers (3x 2 L) with 0.22 µm membrane filters. | Core device allowing chemical exchange between inner chambers and outer sediment slurry. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Apparatus Sterilization: Sterilize the entire microbial aquarium assembly (outer box and inner chambers) with 75% (v/v) ethanol. Rinse with particle-free molecular grade water and dry under UV light in a laminar flow hood for 12 hours [4].

- Sample Inoculation:

- Incubation and Maintenance:

- Seal the apparatus with glass lids and incubate at 25°C for 4 weeks.

- Homogenize the outer chamber continuously using an electric rotator.

- Manually stir the inner chambers with a sterile pipette at 72-hour intervals to prevent sedimentation [4].

- Monitoring and Sub-cultivation:

- Periodically sample from the inner chambers to monitor microbial growth via microscopy or optical density.

- After the incubation period, streak samples from the inner chambers onto low-nutrient agar plates (e.g., 50% Marine 2216E) to obtain pure isolates.

- Identification and Characterization:

- Purify colonies through successive streaking.

- Identify isolates via 16S rRNA gene sequencing and compare with databases to determine novelty [8].

Workflow and Conceptual Framework

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and core principles of the diffusion-based cultivation approach, contrasting it with the traditional method.

The limitations of traditional cultivation media and conditions are a significant bottleneck in marine microbiology. These methods are fundamentally mismatched with the ecological realities of most marine microbes, which have evolved complex dependencies and adaptations to their specific environments. The development of diffusion-based cultivation techniques, such as the microbial aquarium, represents a paradigm shift. By prioritizing the recreation of key aspects of the natural habitat—specifically chemical exchange, low-nutrient conditions, and complex carbon sources—these methods have demonstrated a remarkable ability to bring previously uncultured marine bacteria into pure culture. The continued adoption and refinement of these integrative approaches are essential for illuminating the vast and unexplored microbial dark matter of the oceans, with profound implications for science and industry.

A paradigm shift is underway in environmental microbiology. For decades, the vast majority of marine bacteria—often cited as >99%—remained uncultured and uncharacterized in the laboratory, creating a substantial knowledge gap in our understanding of microbial ecosystems [8] [2]. This "microbial dark matter" represents an immense untapped reservoir of genetic and metabolic diversity with profound implications for biotechnology, drug discovery, and fundamental ecology [16]. The central barrier to cultivation has been our inability to replicate the complex environmental conditions that these microorganisms require for growth under laboratory settings [8] [14].

Diffusion-based cultivation methods have emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge by fundamentally reimagining the relationship between the laboratory and natural environments. Rather than attempting to bring microorganisms entirely into artificial conditions, these innovative approaches bridge the two worlds by allowing continuous chemical exchange while containing target cells for isolation [17]. This article explores the core principles underpinning these methods, examining how they mimic natural habitats to access previously uncultured marine bacteria, with specific applications for research and drug development professionals.

Core Principles of Diffusion-Based Cultivation

Recreating the Natural Chemical Environment

The foundational principle of diffusion-based cultivation is the maintenance of a natural chemical environment through semi-permeable membranes. These membranes create physical boundaries that contain microbial cells while permitting the free passage of nutrients, signaling molecules, growth factors, and metabolites between the natural environment and the cultivation chamber [17] [18]. This continuous exchange ensures that microorganisms receive the complex combination of chemical cues and nutrients they evolved to utilize, which are often unknown to researchers and therefore impossible to replicate precisely in conventional media [8].

This permeability is crucial because marine microbial habitats feature intricate chemical gradients and nutrient flows that are dynamic and challenging to reconstruct artificially. In traditional cultivation, the static nature of petri dishes and culture tubes fails to capture these dynamics, favoring fast-growing generalists over slow-growing specialists adapted to specific microenvironments [8] [11]. Diffusion-based systems maintain these essential chemical connections, providing previously uncultured bacteria with the specific conditions they need to resume growth and division.

Facilitating Microbial Interactions

Microbes in natural environments exist within complex communities characterized by diverse interactions including symbiosis, competition, cross-feeding, and quorum sensing [16] [14]. These social dynamics profoundly influence microbial growth, physiological states, and metabolic activities, yet they are largely eliminated in traditional pure culture isolation methods [16]. Diffusion-based cultivation preserves these critical interactions by allowing chemical communication between the trapped cells and the external environment [8].

The semi-permeable membranes enable the exchange of signaling molecules, peptides, siderophores, and quinones that mediate microbial interactions [8]. This principle is particularly important for species that depend on metabolic byproducts from other organisms or require quorum-sensing signals to initiate growth. By maintaining these communication channels, diffusion methods provide the social context many microbes need to grow, effectively overcoming the isolation-induced "shock" of conventional pure culture techniques [14].

Simulating Natural Substrate Availability

Marine sediments and water columns contain complex organic matter, including recalcitrant substrates that serve as natural carbon sources for diverse microbial communities [8]. Traditional cultivation media typically rely on simple, labile organic compounds that favor fast-growing generalists, while diffusion-based approaches allow microorganisms to access their natural substrates at environmentally relevant concentrations [8].

In deep-sea sediments, for instance, dissolved organic matter is predominantly composed of recalcitrant carbon compounds that sustain slow-growing, specialized bacteria [8]. Diffusion chambers placed in such environments enable trapped cells to utilize these natural substrates through the membrane barrier. Research has demonstrated that media containing recalcitrant organic substrates like lignin can improve enrichment of previously uncultured sedimentary microbial groups [8]. This principle of providing access to natural substrate pools represents a significant advantage over defined laboratory media.

Performance and Efficacy Data

Quantitative Comparison of Cultivation Approaches

Table 1: Performance comparison of diffusion-based versus traditional cultivation methods

| Method | Novelty Ratio | Novel Taxa Levels Identified | Phyla Recovered | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion-Based Integrative Approach (DICA) | 58% (115/196 isolates) | 39 at genus level, 4 at family level | 12 different classes | "Microbial aquarium" design with low-nutrient media containing recalcitrant substrates |

| Traditional Cultivation | 12% (20/165 isolates) | All at species level only | 6 classes | Defined rich media (e.g., marine agar 2216E) |

| Continuous-Flow Bioreactor | Higher novel species ratio than SDP | Multiple novel species | Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Alpha-/Gammaproteobacteria | Maintains low substrate concentration, uses porous carrier materials |

| In Situ I-tip Cultivation | Higher novel species ratio than SDP | Multiple novel species | Bacteroidetes, Alpha-/Gammaproteobacteria | Provides "growth initiation factors" from natural environment |

The quantitative superiority of diffusion-based methods is evident across multiple studies. The Diffusion-based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA) developed by Ahmad et al. demonstrated a nearly five-fold increase in novelty ratio compared to traditional methods (58% versus 12%), recovering twice the number of microbial classes [8]. This substantial enhancement underscores the effectiveness of principles that better mimic natural environments.

Similarly, studies of sponge-associated bacteria found that advanced methods including continuous-flow bioreactors and in situ cultivation yielded higher phylogenetic diversity than standard direct plating, with Shannon-Weaver diversity indexes of 21.9 and 19.1 respectively, compared to 10.8 for conventional methods [14]. Importantly, each method recovered largely non-overlapping sets of species, suggesting they access different portions of the microbial "dark matter" through distinct mechanisms [17] [14].

Accessing Rare and Previously Uncultured Taxa

Table 2: Previously uncultured microbial groups successfully cultivated using diffusion-based methods

| Environment | Method | Previously Uncultured Groups Recovered | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Sediment | DICA | Verrucomicrobiota, Balneolota | Rarely cultivated phyla despite widespread detection in molecular surveys |

| Marine Sponge | I-tip In Situ Cultivation | Novel species of Bacteroidetes, Alpha-/Gammaproteobacteria | Access to symbiotic bacteria with potential for bioactive compound production |

| High Arctic Lake Sediment | Diffusion Chambers | Unique OTUs from Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes | Demonstration that multiple approaches are necessary to capture full diversity |

| Various Environments | Ichip | Multiple novel species across diverse habitats | High-throughput adaptation enabling cultivation of "uncultivable" species |

The true measure of success for any novel cultivation method is its ability to access microbial taxa that have consistently resisted previous cultivation attempts. Diffusion-based approaches have demonstrated remarkable capability in this regard, successfully cultivating members of rarely isolated phyla such as Verrucomicrobiota and Balneolota from marine sediments [8]. These groups have been widely detected in molecular surveys from various ecosystems, often in high abundance, but have remained largely inaccessible for laboratory study until now [8].

The ecological significance of these breakthroughs extends beyond simply adding new names to microbial databases. Each newly cultivated representative from previously inaccessible groups provides opportunities to understand their physiological characteristics, metabolic capabilities, and ecological roles in natural environments [2] [16]. For drug development professionals, these novel isolates represent untapped resources for discovering new bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic applications [16].

Experimental Protocols

Diffusion-Based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA)

Apparatus Design and Setup The DICA method employs a "microbial aquarium" consisting of a rectangular glass outer chamber (30 L capacity: 50 × 30 × 20 cm) containing three inner, semi-permeable cylindrical glass chambers (2 L each: 10 × 24 × 8 cm) [8] [4]. Each inner chamber is perforated with 15 holes (6 mm diameter) covered with 0.22 µm pore size polycarbonate membrane filters, firmly attached using laboratory-grade glue [8]. This design creates a nested system where inner chambers contain the target inoculum and growth media, while the outer chamber holds natural sediment slurry to maintain environmental conditions.

Media Preparation and Inoculation For marine sediment bacteria, three modified low-nutrient media are recommended: (1) 0.5% alkali-lignin in artificial seawater (Lig-medium), (2) 0.5% starch in artificial seawater (St-medium), and (3) artificial seawater alone (ASW-medium) as a control [8]. The artificial seawater base should contain essential ions: 26.0 g/L NaCl, 5.0 g/L MgCl₂·6H₂O, 1.4 g/L CaCl₂·2H₂O, 4.0 g/L Na₂SO₄, 0.3 g/L NH₄Cl, 0.1 g/L KH₂PO₄, 0.5 g/L KCl, supplemented with 1.0 mL trace element mixture, 30.0 mL 1 mol/L NaHCO₃ solution, 1.0 mL vitamin mixture, 1.0 mL thiamine solution, and 1.0 mL vitamin B12 solution [8]. After sterilization, add 0.25 g of sediment inoculum with 500 mL of media to each inner chamber; the outer chamber should contain 75 g of sediment mixed with 15 L of artificial seawater [8].

Incubation and Monitoring Incubate the entire apparatus at 25°C for 4 weeks [8]. To maintain homogeneity, use an electric rotator in the outer container and manually stir inner chambers with a sterile pipette at 72-hour intervals [8]. Monitor microbial growth periodically through sampling. For isolation, subsequently sub-culture using 50% diluted marine 2216E and R2A agar media for plate cultivation [8].

In Situ I-tip Cultivation Protocol

Device Construction The I-tip device is constructed from a sterile 200 µL pipette tip, with the lower portion filled with acid-washed glass beads of varying sizes (60-200 µm diameter) to prevent invasion of larger organisms [17] [14]. The tip is then filled with sterilized media mixed with 0.7% agar above the glass beads [14]. The narrow tip opening is placed just under the sediment surface, while the opposite end is sealed with waterproof silicone adhesive [14].

Deployment and Recovery Deploy multiple I-tip devices in the target environment for 2-4 weeks to allow microbial colonization [14]. Following incubation, carefully recover devices and transfer content to laboratory conditions for further analysis and sub-culturing [14].

Continuous-Flow Bioreactor Cultivation

Bioreactor Configuration The continuous-flow (CF) bioreactor system utilizes porous materials such as polyester nonwoven fabric or polyurethane sponge as carrier material to provide adequate pore space and enlarged surface area for microbial growth [14]. The reactor is designed to maintain low substrate concentrations and high flow rate conditions, creating an environment conducive for slow-growing organisms [14].

Operation Parameters Operate the CF bioreactor with a continuous flow of low-nutrient media, maintaining conditions that mimic the natural environment of the target microorganisms [14]. The extended residence time and constant nutrient flow support the enrichment of K-strategists and bacterial types inhibited by their own growth metabolites in batch cultures [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for diffusion-based cultivation

| Item | Specification | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate Membrane | 0.22 µm or 0.03 µm pore size | Permits chemical exchange while containing cells | Critical pore size selection affects diffusion rates and cell containment [8] [17] |

| Artificial Seawater Base | Defined ion composition | Provides essential marine ions | Foundation for media preparation; maintain natural ion ratios [8] |

| Recalcitrant Organic Substrates | Alkali-lignin (0.5%) | Carbon source for specialized microbes | Mimics natural dissolved organic matter in sediments [8] |

| Trace Element Mixture | Comprehensive metal ions | Supports diverse metalloenzymes | Critical for organisms with specific metal requirements [8] |

| Vitamin Supplements | B-vitamins, thiamine, B12 | Cofactors for fastidious organisms | Essential for species lacking biosynthetic pathways [8] |

| Polyester Carrier Material | Nonwoven fabric or polyurethane sponge | Provides attachment surface in CF bioreactors | Increases surface area for biofilm formation [14] |

| Glass Beads | Acid-washed, 60-200 µm | Controls cell entry in I-tip devices | Prevents larger organisms from entering cultivation chamber [14] |

| N-Cyclopropyl Bimatoprost | N-Cyclopropyl Bimatoprost | N-Cyclopropyl Bimatoprost is a synthetic prostaglandin analog for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Biotinyl-Somatostatin-14 | Biotinyl-Somatostatin-14, MF:C86H118N20O21S3, MW:1864.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Mechanisms of Success: Scientific Basis

The remarkable success of diffusion-based cultivation methods can be attributed to several interconnected biological mechanisms that address fundamental limitations of traditional approaches:

Overcoming Metabolic Dependence Many uncultured marine bacteria exist in complex metabolic relationships with other organisms in their natural environment, depending on cross-feeding or metabolic byproducts they cannot synthesize themselves [16] [14]. The continuous exchange enabled by semi-permeable membranes allows these dependencies to be maintained, providing essential metabolites that would be absent in defined laboratory media [8]. This principle explains why some bacteria cultivated in diffusion chambers can subsequently be adapted to laboratory conditions—the initial growth period in the chamber allows them to activate dormant metabolic pathways or adapt to alternative nutrient sources [14].

Signaling-Mediated Growth Activation Research has identified the presence of "growth initiation factors" in natural environments that can stimulate bacterial resuscitation from a non-growing state [14]. These signaling-like compounds, which may include peptides, siderophores, or other molecules, diffuse through the membrane and trigger growth initiation in previously dormant cells [8] [14]. This mechanism is particularly important for bacteria that exist in viable but non-culturable (VBNC) states or require quorum-sensing signals to activate growth programs [2].

Mitigation of Growth Inhibitors Traditional batch cultivation in closed systems often leads to the accumulation of metabolic byproducts that can inhibit further growth, particularly for slow-growing organisms [14]. Diffusion-based systems continuously remove these inhibitors while introducing fresh nutrients, preventing their buildup to toxic concentrations [8] [14]. This principle is especially important for K-strategists (slow-growing organisms adapted to stable, low-nutrient environments) that would be outcompeted in traditional rich media [14].

Diffusion-based cultivation methods represent a fundamental advancement in environmental microbiology by creatively addressing the core challenge of microbial uncultivability. Through principles that maintain natural chemical environments, facilitate microbial interactions, and provide appropriate substrate availability, these approaches have successfully accessed previously untapped microbial diversity from marine ecosystems [8] [17] [14]. The substantial increase in novelty ratios—from 12% with traditional methods to 58% with diffusion-based approaches—demonstrates the profound efficacy of these techniques [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these methodologies offer powerful tools to access the immense biotechnological potential of microbial dark matter [16]. The cultivation of novel taxa from previously inaccessible phylogenetic groups opens new frontiers for discovering bioactive compounds, novel enzymes, and understanding fundamental microbial processes [2] [16]. As these protocols become more refined and widely adopted, they promise to transform our relationship with the microbial world, turning what was once considered "unculturable" into valuable resources for scientific and therapeutic advancement [8] [14].

For over a century, microbiologists have faced a fundamental challenge known as the "Great Plate Count Anomaly" – the observation that only about 1% of environmental microorganisms can be cultivated using standard laboratory techniques [19]. This limitation has represented a significant bottleneck in microbial research and natural product discovery, leaving the vast majority of bacterial species, often referred to as "microbial dark matter," unexplored and uncharacterized [20]. The development of diffusion-based cultivation methods has progressively addressed this challenge, evolving from simple diffusion chambers to sophisticated high-throughput platforms that enable researchers to access previously unculturable microorganisms from diverse marine environments [19] [21].

Historical Progression of Diffusion-Based Technologies

The historical development of diffusion-based cultivation methods represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, moving from artificial laboratory conditions toward approaches that maintain microorganisms in their natural environmental context.

The Diffusion Chamber (2002)

The initial breakthrough came in 2002 with the development of a diffusion chamber that addressed a fundamental limitation of conventional cultivation [19]. This early device consisted of a simple design where bacterial samples were sandwiched between a breathable material containing pores sufficiently large to permit the passage of nutrients and waste products, yet small enough to retain the bacterial cells inside [19]. When incubated in the original environmental setting, this chamber demonstrated a remarkable 30,000% increase in bacterial colony growth compared to standard agar plates [19]. However, this initial design had a significant limitation: it could not isolate specific bacterial strains, as it typically contained multiple species simultaneously [19].

The Isolation Chip (iChip) (2010)

In 2010, researchers transformed the diffusion chamber concept into a high-throughput technology platform with the development of the iChip [21]. This innovative device consisted of a central plate manufactured from hydrophobic plastic (polyoxymethylene) containing 192-384 tiny wells, each approximately 1 mm in diameter [21]. The manufacturing process involved precisely machining these plates with multiple registered through-holes arranged in systematic arrays [21]. The operational principle involved dipping the central plate into a diluted bacterial suspension mixed with a gelling agent, resulting in individual cells becoming trapped in separate wells [21]. Semi-permeable membranes (typically 0.03 μm pore size polycarbonate membranes) were then secured to both sides of the central plate, effectively creating hundreds of miniature diffusion chambers [21]. The entire assembly was incubated in the native environment of the sampled microorganisms, allowing natural nutrients and growth factors to diffuse through the membranes and support the growth of previously uncultivable species [21].

Table 1: Key Developmental Stages of Diffusion-Based Cultivation

| Technology | Development Year | Key Innovation | Cultivation Efficiency | Limitations Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Chamber | 2002 [19] | Permeable membrane allowing environmental nutrient exchange | 30,000% increase over agar plates [19] | Enabled environmental nutrient access |

| Standard iChip | 2010 [21] | High-throughput platform with 192-384 miniature diffusion chambers | Significant increase over standard cultivation [21] | Enabled single-cell isolation and massively parallel cultivation |

| Modified iChip | 2023 [22] | Polypropylene material, gellan gum substitute, glued membranes | Successful isolation of 107 strains from hot springs [22] | Adapted for extreme environments (85°C thermal tolerance) |

Recent Advancements and Modifications (2018-2024)

Recent years have witnessed further refinements and applications of iChip technology, including:

- Modified iChip for Extreme Environments (2023): Researchers successfully adapted the iChip for thermo-tolerant microorganisms from hot springs (85°C) by replacing agar with gellan gum and using polypropylene plastic with glued membranes for improved thermal and chemical stability [22].

- Diffusion-based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA) (2024): This system featured a "microbial aquarium" design with inner chambers separated by 0.22 µm membrane filters, achieving a 58% novelty ratio (115 previously uncultured taxa out of 196 isolates) from marine sediments [4].

- iChip-Inspired Filtration Plates (2022): Research demonstrated the use of commercial MultiScreen 96-Well Filtration Plates with 0.22 µm hydrophilic polyvinylidene fluoride filters to simulate miniature diffusion chambers, successfully isolating marine Actinomycetota with bioactive potential [23].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The effectiveness of diffusion-based cultivation methods is clearly demonstrated through comparative performance metrics across multiple studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cultivation Methods Across Studies

| Cultivation Method | Environment | Novelty Rate/Novel Taxa | Total Isolates | Phylogenetic Diversity | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Cultivation | Marine Sediment | 12% novel isolates [4] | 165 [4] | 6 classes [4] | [4] |

| DICA Method | Marine Sediment | 58% novel taxa (115/196) [4] | 196 [4] | 12 classes [4] | [4] |

| Standard iChip | Various Environments | "Significant phylogenetic novelty" [21] | Not specified | "Far superior" diversity [21] | [21] |

| Modified iChip | Hot Spring | 25 previously uncultured strains [22] | 133 [22] | 19 genera [22] | [22] |

| iChip-Inspired | Marine Beach Sediment | 96 strains of Actinomycetota [23] | 158 [23] | Multiple novel taxa [23] | [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Principle: The iChip enables high-throughput in situ cultivation by creating hundreds of miniature diffusion chambers that allow environmental nutrients and growth factors to reach individually isolated cells while preventing their escape.

Materials:

- Central plate (72 × 19 × 1 mm) with 192-384 through-holes (1 mm diameter)

- Two symmetrical top and bottom plates (72 × 19 × 6.5 mm)

- 0.03 μm pore size polycarbonate membranes (47 mm diameter)

- Sterile Delrin plastic components

- Diluted growth medium with gelling agent

Procedure:

- Sterilization: Sterilize all iChip components in ethanol, followed by drying in a laminar flow hood and rinsing in particle-free DNA-grade water.

- Cell Preparation: Create a diluted cell suspension in warm (45°C), diluted (0.1% w/v) LB agar to achieve approximately one cell per through-hole volume.

- Inoculation: Dip the central plate into the cell-agar mixture, allowing each through-hole to capture a small volume containing, on average, one bacterial cell.

- Membrane Application: Apply membranes to both sides of the central plate, ensuring complete coverage of the through-hole arrays.

- Assembly: Align top and bottom plates and tighten screws to provide pressure, creating 384 separate miniature diffusion chambers.

- Incubation: Incubate the assembled iChip in the original environmental habitat for a period of typically 2-6 weeks.

- Recovery: Disassemble the iChip and extract grown colonies from individual wells for further analysis and subculturing.

Adaptations for Thermal Tolerance:

- Material Substitution: Replacement of standard materials with polypropylene plastic (5 mm thickness, 5 cm diameter) with 37 holes (3 mm diameter each).

- Gelling Agent: substitution of agar with 20% gellan gum for improved thermal stability.

- Membrane Attachment: Direct adhesion of PCTE membranes (0.03 μm pore size) to the central plate using RTV 108 glue instead of mechanical fasteners.

- Inoculation: Precise application of 10 μL hot spring samples into each hole after gellan gum solidification.

- Incubation: Floating incubation in water bath at 85°C for 8 weeks with weekly replenishment of hot spring water.

Simplified Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Create cell suspension from marine sediment in sterile seawater.

- Cell Counting: Determine cell density using a Thoma counting chamber.

- Gelled Suspension: Prepare mixture of sterile natural seawater with agar (0.8% w/v) containing approximately 10 cells per 100 μL.

- Inoculation: Seed 100 μL of suspension into each well of a MultiScreen 96-Well Filtration Plate.

- Sealing: Seal the plate with Parafilm and place in a box with filter end covered with wet sediment from the sampling site.

- Incubation: Maintain in darkness at room temperature for 60 days.

- Transfer: Inoculate grown cells into appropriate medium (e.g., M600 medium) for further analysis.

Visualization: Historical Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for iChip Experiments

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate Membranes | 0.03 μm pore size; enables nutrient diffusion while containing cells | Critical for creating diffusion barrier; affects molecular weight cutoff | [21] |

| Gelling Agents | Agar (standard), Gellan Gum (high-temperature), Low-melting-point Agarose | Choice depends on temperature requirements and chemical compatibility | [21] [22] |

| Growth Media | Diluted LB agar (0.1%), Marine-specific supplements | Low nutrient concentrations often mimic natural conditions better | [21] |

| Chip Materials | Delrin (standard), Polypropylene (high-temperature) | Material compatibility with environmental conditions essential | [21] [22] |

| Sealing Materials | Screws (standard), RTV 108 glue (high-temperature) | Ensures chamber integrity during extended incubation periods | [22] |

| Cell Suspension Buffer | Sterile seawater, Particle-free DNA-grade water | Maintains osmotic balance and cell viability during inoculation | [23] [21] |

| 3,5,6-Trichloro-2-pyridinol-13C5 | 3,5,6-Trichloro-2-pyridinol-13C5, CAS:1330171-47-5, MF:C5H2Cl3NO, MW:203.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Colterol hydrochloride | Colterol hydrochloride, CAS:52872-37-4, MF:C12H20ClNO3, MW:261.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Significant Applications and Discoveries

The implementation of iChip technology has led to several groundbreaking discoveries with particular relevance to marine drug discovery:

Antibiotic Discovery

The most prominent success of iChip technology has been the discovery of teixobactin, a novel class of antibiotic from a previously uncultured soil bacterium, Eleftheria terrae [19]. This discovery was particularly significant because:

- Teixobactin represents the first new class of antibiotics discovered in decades [20]

- It demonstrates activity against several drug-resistant pathogens [20]

- The producing bacterium had resisted all previous cultivation attempts using standard methods [19]

Marine Natural Product Discovery

Application of iChip and diffusion-based methods to marine environments has yielded significant results:

- Isolation of 96 strains of Actinomycetota from marine sediments, with 53 strains containing genes for polyketide synthase (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) – key enzymes in antibiotic production [23]

- 11 strains demonstrated antimicrobial activity against clinically relevant pathogens including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [23]

- Discovery of multiple previously uncultured taxa from marine sediments with potential for novel bioactive compound production [4] [23]

Extreme Environment Microbiome Exploration

Modified iChip approaches have enabled access to microbial diversity in previously inaccessible niches:

- Successful cultivation of 107 bacterial strains from hot spring environments at 85°C, including 25 previously uncultured strains [22]

- Isolation of thermo-tolerant species from genera including Alkalihalobacillus, Lysobacter, and Agromyces with previously unrecognized heat tolerance [22]

- Expansion of cultivable microbial diversity to include representatives from rarely cultivated phyla such as Verrucomicrobiota and Balneolota [4]

The historical development from simple diffusion chambers to sophisticated iChip technology represents a transformative advancement in marine microbiology. By maintaining the connection between microorganisms and their natural chemical environment during cultivation, these methods have effectively addressed the century-old challenge of the Great Plate Count Anomaly. The continued refinement of these platforms – including adaptations for extreme environments, integration with molecular screening approaches, and miniaturization for increased throughput – promises to further expand access to Earth's microbial dark matter. For researchers focused on marine drug discovery, these technologies offer a powerful pathway to access the extensive biosynthetic potential of previously uncultured marine bacteria, opening new frontiers in natural product discovery and development.

A Guide to Diffusion-Based Techniques: From Microbial Aquariums to In Situ Cultivation

The pursuit of cultivating environmental microorganisms in the laboratory is a fundamental yet challenging endeavor in microbiology. Despite their ecological significance, a vast majority of marine bacteria have remained uncultured and uncharacterized using traditional cultivation methods (TCA) [4]. This gap in our understanding is largely due to the inability of conventional techniques to replicate the complex chemical and physical conditions of natural habitats, particularly the subtle microbial interactions and nutrient gradients essential for growth [4]. To address this, a diffusion-based integrative cultivation approach (DICA), featuring a novel device termed the "microbial aquarium," has been developed. This apparatus and its associated protocols are designed to efficiently isolate novel taxonomic candidates from marine sediments by better mimicking their natural environment, thereby facilitating the cultivation of previously uncultured bacteria for downstream applications in research and drug discovery [4].

Apparatus Design and Specifications

The core of the DICA method is the "microbial aquarium," a multi-chamber apparatus that facilitates the exchange of chemical signals and metabolites between a simulated natural environment and inner cultivation chambers.

Physical Dimensions and Components

The apparatus is constructed with the following key components and dimensions [4]:

- Outer Chamber: A rectangular glass box serving as the main reservoir, with a capacity of 30 liters and dimensions of 50 cm (width) × 30 cm (height) × 20 cm (depth).

- Inner Chambers: Three semi-permeable cylindrical glass chambers are housed within the outer container. Each inner chamber has a 2 L capacity, with dimensions of 10 cm (width) × 24 cm (height) × 8 cm (depth).

- Semi-Permeable Barriers: Each inner chamber is perforated with 15 holes, each 6 mm in diameter. These holes are covered with a 0.22 µm pore size polycarbonate membrane filter, which allows for the free diffusion of water, nutrients, and signaling molecules while containing bacterial cells within their respective compartments.

Configuration and Setup

The experimental setup is designed to create a bridge between a natural sediment slurry and controlled growth media [4]:

- The outer chamber is filled with a 0.5% (w/v) sediment slurry prepared from the same sample intended for cultivation, mixed with 15 L of artificial seawater (ASW).

- The three inner chambers are each loaded with 0.25 g of sediment sample and 500 mL of a specific nutrient medium: Lig-medium (0.5% alkali-lignin), St-medium (0.5% starch), or ASW-medium (artificial seawater alone).

- The entire apparatus is kept at a constant temperature of 25 °C for an incubation period of 4 weeks.

The following diagram illustrates the structure and flow of materials within the microbial aquarium:

Operational Protocol

Apparatus Preparation and Sterilization

- Sterilization: Prior to use, the entire microbial aquarium apparatus must be thoroughly sterilized. This is achieved by washing with 75% (v/v) ethanol, rinsing with particle-free molecular grade water, and then drying under a UV light (e.g., TUV 8W/G8 T5) in a laminar flow hood for 12 hours [4].

- Assembly: Firmly attach the 0.22 µm polycarbonate membrane filters over the holes of the inner chambers using a suitable, non-toxic adhesive (e.g., 08d-2 Contact CR glue). Place the three inner chambers inside the sterilized outer container [4].

- Loading:

- Fill the outer chamber with 75 g of sediment mixed with 15 L of Artificial Seawater (ASW) to create the slurry.

- In each of the three inner chambers, add 0.25 g of sediment along with 500 mL of one of the three pre-prepared media: Lig-medium, St-medium, or ASW-medium.

- Sealing: Tightly cover the openings of the inner chambers with their glass lids and seal the outer chamber with a glass cover sheet to create a closed system [4].

Incubation and Maintenance

- Incubation Conditions: Place the fully assembled apparatus in a temperature-controlled environment set to 25 °C for 4 weeks [4].

- Homogenization: To maintain homogeneity and promote diffusion, employ gentle stirring.

- In the outer chamber, use an electric rotator for continuous, gentle mixing.

- In the inner chambers, manually stir the contents using a sterile 25 mL pipette at 72-hour intervals [4].

- Contamination Control: Perform all loading and maintenance steps under sterile conditions, such as within a laminar flow hood, to prevent airborne microbial contamination [4].

Post-Incubation Processing and Isolation

After the 4-week incubation, proceed with bacterial isolation [4]:

- Sub-cultivation: Sample the contents from each inner chamber and sub-culture onto solid agar plates. The recommended solid media are 50% diluted marine 2216E agar and R2A agar.

- Purification: Isolate individual colonies from the sub-culture plates and purify them through repeated streaking.

- Identification: Identify the isolated pure cultures using 16S rRNA gene sequencing to determine phylogenetic novelty.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful application of the DICA protocol relies on a set of specifically formulated reagents and media.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for the DICA Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Components / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) [4] | Base medium for preparing sediment slurry and dilution; provides essential ions and a marine-simulated environment. | NaCl (26.0 g/L), MgCl₂·6H₂O (5.0 g/L), CaCl₂·2H₂O (1.4 g/L), Na₂SO₄ (4.0 g/L), NH₄Cl (0.3 g/L), KH₂PO₄ (0.1 g/L), KCl (0.5 g/L), trace elements, vitamins, NaHCO₃. |

| Lig-Medium [4] | Modified low-nutrient enrichment medium; uses recalcitrant carbon (lignin) to select for bacteria capable of degrading complex organic matter. | ASW base supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) alkali-lignin. |

| St-Medium [4] | Modified low-nutrient enrichment medium; uses starch as a complex polysaccharide carbon source. | ASW base supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) starch. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane [4] | Semi-permeable physical barrier; allows free diffusion of molecules while containing bacterial cells within specific chambers. | 0.22 µm pore size. |

| Solid Sub-culture Media [4] | For isolation and purification of colonies after the enrichment period in the microbial aquarium. | 50% diluted marine 2216E agar and R2A agar. |

Performance and Experimental Outcomes

The efficacy of the DICA method was quantitatively evaluated against a Traditional Cultivation Approach (TCA), demonstrating its superior ability to access microbial diversity.

Quantitative Comparison of Cultivation Efficiency

The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of the bacterial diversity cultivated by DICA versus TCA, based on 16S rRNA gene identification of isolates [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DICA vs. Traditional Cultivation (TCA)

| Performance Metric | DICA (Diffusion-Based Approach) | TCA (Traditional Approach) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Isolates Recovered | 196 | 165 |

| Previously Uncultured Taxa | 115 | 20 |

| Novelty Ratio | 58% | 12% |

| Highest Taxonomic Level of Novelty | 39 genera, 4 families | Species level only |

| Phyla Recovered | Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota, Verrucomicrobiota, Balneolota | Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota |

| Classes Represented | 12 | 6 |

Experimental Workflow

The complete experimental workflow, from sample collection to final identification, is outlined in the following diagram:

Discussion

The Microbial Aquarium (DICA) represents a significant advancement in cultivation technology. Its design directly addresses two major obstacles in cultivating environmental microbes: the lack of natural chemical cues and the use of overly rich artificial media [4]. By enabling a continuous exchange of metabolites and signaling molecules between the sediment slurry in the outer chamber and the enclosed media, DICA partially recreates the chemical landscape of the original habitat. This is crucial for supporting the growth of bacteria that depend on interactions with other community members [4].

The integration of low-nutrient media with complex carbon sources like lignin and starch further selects for oligotrophic bacteria adapted to nutrient-poor environments, which are often missed by TCA that use high-nutrient media [4]. The outstanding performance of DICA, evidenced by its high novelty ratio and recovery of rare phyla like Verrucomicrobiota, validates this integrative strategy [4]. For researchers in drug discovery, DICA provides a powerful tool to access a previously untapped reservoir of microbial genetic and metabolic diversity, opening new avenues for the discovery of novel bioactive compounds.

Over 99% of marine bacteria have historically resisted cultivation in laboratory settings, creating a significant gap in our understanding of microbial diversity and function [8] [2]. Traditional cultivation methods often rely on nutrient-rich media that favor fast-growing organisms, inadvertently excluding the vast majority of microbial taxa adapted to oligotrophic conditions [8] [4]. The failure to replicate key aspects of natural marine environments—particularly the chemical complexity of native dissolved organic matter (DOM)—represents a fundamental limitation in conventional approaches [24].

Advanced diffusion-based cultivation systems, such as the Diffusion-based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA), have demonstrated remarkable success by strategically incorporating low-nutrient media and recalcitrant carbon sources that better mimic the natural sedimentary environment [8] [25]. These methodological innovations have enabled researchers to access previously uncultivated microbial lineages, including members of the rarely cultivated phyla Verrucomicrobiota and Balneolota [8]. This protocol details the formulation and application of specialized media components essential for cultivating the microbial "dark matter" of marine sediments.

Theoretical Foundation

In deep-sea sediments, dissolved organic matter is predominantly composed of recalcitrant carbon compounds that serve as the primary carbon source for in situ microbial communities [8]. Unlike labile substrates such as glucose or pyruvate that stimulate rapid growth of generalist bacteria, complex organic molecules support a more diverse microbial consortium by mimicking the natural chemical environment [8] [24].

Bacterial processing of organic matter generates exometabolites of remarkable molecular and structural diversity, with a significant fraction possessing properties consistent with refractory molecules that persist in marine environments [24]. This microbial transformation of simple biochemicals into complex molecular mixtures represents a crucial mechanism in the marine carbon cycle and provides the scientific basis for incorporating recalcitrant substrates into cultivation media [24]. The strategic use of these substrates creates a positive feedback between primary production and refractory DOM formation, effectively simulating the natural microbial carbon pump in laboratory settings [24] [26].

Ecological Basis for Low-Nutrient Conditions

High-nutrient concentrations typically favor fast-growing, opportunistic taxa while inhibiting the growth of oligotrophic specialists adapted to nutrient-scarce environments [8] [27]. Low-nutrient media reduces competitive exclusion and allows slow-growing bacteria to establish colonies without being overgrown by generalist species [8] [11]. The concentration of organic substrates in natural marine environments is typically orders of magnitude lower than in conventional laboratory media, creating a fundamental mismatch that has contributed to the "great plate count anomaly" where <1% of environmental microbes form colonies on standard media [11].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cultivation Approaches Using Different Media Formulations

| Cultivation Method | Media Type | Novelty Ratio | Phyla Recovered | Previously Uncultured Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DICA [8] | Lignin-based low-nutrient | 58% (115/196) | 12 classes across multiple phyla | 39 genera, 4 families |

| DICA [8] | Starch-based low-nutrient | 58% (115/196) | 12 classes across multiple phyla | 39 genera, 4 families |

| Traditional Approach [8] | Conventional rich media | 12% (20/165) | 6 classes across common phyla | Species level only |

| Novel Soil Technique [27] | Soil extract-based | 35 previously uncultured strains | 4 phyla | 35 uncultured soil bacteria |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Media Components for Cultivating Previously Uncultured Marine Bacteria

| Reagent Category | Specific Components | Final Concentration | Function in Cultivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recalcitrant Carbon Sources | Alkali-lignin | 0.5% (w/v) | Mimics natural sedimentary carbon; selects for specialists |

| Starch | 0.5% (w/v) | Complex carbohydrate source; encourages diversity | |

| Basal Salts | NaCl, MgCl₂·6H₂O, CaCl₂·2H₂O, Na₂SO₄ | Varies (see protocol) | Maintains marine ionic environment |

| Nutrient Supplements | NHâ‚„Cl, KHâ‚‚POâ‚„ | 0.3 g/L, 0.1 g/L | Nitrogen and phosphorus sources |

| Trace Elements | SL-10 trace element mixture | 1.0 mL/L | Provides essential micronutrients |

| Vitamin Solutions | Vitamin mixture, thiamine, vitamin Bâ‚â‚‚ | 1.0 mL/L each | Supplies growth factors for fastidious bacteria |

| Buffer System | NaHCO₃ | 30.0 mL/L of 1M stock | pH stabilization in closed systems |

Protocol: Diffusion-Based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA)

Apparatus Design and Assembly

The DICA system employs a "microbial aquarium" consisting of a rectangular glass outer chamber (30 L) housing three inner, semi-permeable cylindrical glass chambers (2 L each) [8]. The specific design parameters are as follows:

- Inner Chamber Modification: Drill 15 holes (6 mm diameter) distributed across the surface of each inner chamber [8]

- Membrane Installation: Cover holes with 0.22 µm pore size polycarbonate membrane filters, firmly attached using aquarium-safe glue [8]

- Apparatus Sterilization: Sterilize the fully assembled system with 75% (v/v) ethanol, rinse with particle-free molecular grade water, and dry under UV light in a laminar flow hood for 12 hours [8]

This design enables continuous chemical exchange between the inner chambers containing the cultivation media and the outer chamber containing native sediment slurry, allowing diffusion of signaling molecules, siderophores, and other essential growth factors [8].

Media Formulation and Preparation

Lignin-Containing Medium (Lig-Medium)

- Prepare artificial seawater base [8]:

- NaCl: 26.0 g/L

- MgCl₂·6H₂O: 5.0 g/L

- CaCl₂·2H₂O: 1.4 g/L

- Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„: 4.0 g/L

- KCl: 0.5 g/L

- Add nutrient components [8]:

- NHâ‚„Cl: 0.3 g/L

- KHâ‚‚POâ‚„: 0.1 g/L

- Incorporate carbon source [8]:

- Alkali-lignin: 5.0 g/L (0.5% w/v)

- Supplement with solutions [8]:

- Trace element mixture (SL-10): 1.0 mL/L

- NaHCO₃ (1 mol/L): 30.0 mL/L

- Vitamin mixture: 1.0 mL/L

- Thiamine solution: 1.0 mL/L

- Vitamin Bâ‚â‚‚ solution: 1.0 mL/L

Starch-Containing Medium (St-Medium)

- Follow the same preparation as Lig-medium but substitute alkali-lignin with 0.5% (w/v) starch as the carbon source [8]

Artificial Seawater Control (ASW-Medium)

- Prepare without additional carbon sources to monitor background growth [8]

Inoculation and Incubation

Sample Inoculation [8]:

- Inner chambers: Add 0.25 g marine sediment + 500 mL test media

- Outer chamber: Add 75 g marine sediment mixed with 15 L artificial seawater

Incubation Conditions [8]:

- Temperature: 25°C

- Duration: 4 weeks

- Mixing: Continuous gentle rotation in outer chamber; manual stirring of inner chambers every 72 hours

Monitoring and Subculturing [8]:

- Periodically sample from inner chambers for community analysis

- Perform serial dilutions in sterilized normal saline (10â»Â¹ to 10â»â¶)

- Plate 100 µL aliquots onto 50% diluted marine 2216E and R2A agar

- Incolate plates aerobically at 25°C for 4 weeks

- Purify colonies through repeated subculturing

Expected Outcomes and Quality Control

Diversity Metrics and Validation

The successful implementation of this protocol should yield substantially enhanced microbial recovery compared to traditional methods. Quality control indicators include [8]:

Novelty Assessment: 16S rRNA gene sequencing should reveal a significantly higher proportion of novel taxa compared to traditional methods (approximately 58% vs 12%) [8]

Diversity Expansion: Recovery of taxa across 12 different bacterial classes, including representatives from rarely cultivated phyla such as Verrucomicrobiota and Balneolota [8]

Taxonomic Validation: Identification of novel isolates at multiple taxonomic levels (species, genus, and family) indicating access to deeper phylogenetic diversity [8]

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Diffusion-Based Cultivation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low diversity recovery | Overly rich media | Further dilute nutrient components (1:10 or 1:100) |

| No growth in inner chambers | Membrane clogging | Verify membrane pore integrity; increase hole diameter to 8-10 mm |

| Contamination | Improper sterilization | Extend UV sterilization to 24 hours; add antifungal agents |

| Limited novel isolates | Insufficient incubation time | Extend incubation to 6-8 weeks for slow-growing taxa |

| Dominance by fast-growing taxa | Excessive nutrient diffusion | Reduce carbon source concentration to 0.1-0.2% |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biotechnology

The strategic application of low-nutrient media with recalcitrant carbon sources enables researchers to access microbial taxa with unique biosynthetic potential [2]. Previously uncultivated bacteria represent an untapped reservoir of novel secondary metabolites, including antibiotics, antitumor compounds, and other pharmacologically active molecules [2]. Cultivation-based approaches have successfully identified novel bioactive compounds that were not detected through metagenomic analyses alone, highlighting the complementary value of traditional microbiology techniques in bioprospecting [11].

The integration of diffusion-based systems with targeted media formulation creates opportunities for microbiome engineering and the development of specialized microbial consortia for biotechnology applications [26]. By mimicking the chemical complexity of natural environments, researchers can cultivate microbial communities that perform coordinated functions, such as the conversion of labile organic matter into refractory compounds that contribute to carbon sequestration [24] [26].

The overwhelming majority of marine bacteria, often exceeding 99%, have never been cultured and characterized in laboratory conditions using traditional cultivation methods [4]. This represents a vast reservoir of unexplored biological diversity and potential, particularly for drug discovery professionals seeking novel bioactive compounds [28] [29]. The Diffusion-based Integrative Cultivation Approach (DICA) is a novel technique designed to overcome this bottleneck by better mimicking a microbe's natural habitat. DICA combines a custom "microbial aquarium" apparatus with modified low-nutrient media, allowing for the diffusion of signaling molecules, nutrients, and other essential factors from the natural environment into the cultivation chamber [4] [8]. This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide for implementing DICA, enabling researchers to access previously uncultured marine bacteria for basic research and pharmaceutical development.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials and reagents required for the successful implementation of the DICA protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for DICA

| Item Name | Function/Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) | Base for preparing all media; provides essential ions and osmotic balance for marine bacteria [4] [8]. |

| Alkali-lignin (Lig-medium) | Recalcitrant carbon source in modified low-nutrient media; promotes growth of bacteria utilizing complex organic matter [4] [8]. |

| Starch (St-medium) | Organic substrate in modified low-nutrient media [4] [8]. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filter (0.22 µm pore size) | Creates a semi-permeable barrier for the inner chambers; allows diffusion of molecules while containing bacterial cells [4]. |

| Trace Element Mixture | Supplement in ASW and media; provides essential micronutrients for bacterial growth [4] [8]. |

| Vitamin Mixture | Supplement in ASW and media; provides essential vitamins for fastidious bacteria [4] [8]. |

| Marine 2216E & R2A Agar (50% diluted) | Used for subsequent sub-cultivation and isolation of pure strains on solid media [4] [8]. |

Equipment and Apparatus

- Microbial Aquarium: A rectangular glass outer chamber (30 L, approx. 50 cm x 30 cm x 20 cm) and three inner, cylindrical glass chambers (2 L each, approx. 10 cm x 24 cm x 8 cm) [4].

- Electric Rotator: Placed in the outer chamber to stir and homogenize the sediment slurry [4].

- Sterile Pipettes (e.g., 25 mL): For manual stirring of the inner chambers.

- Laminar Flow Hood: For sterile assembly and handling.

- UV Light Source (e.g., TUV 8W/G8 T5 Philips): For sterilization of the apparatus.

- Incubator: Capable of maintaining a stable temperature of 25°C.

Experimental Procedures

Apparatus Preparation and Sterilization

- Drill Holes: Drill 15 holes, each 6 mm in diameter, evenly over the surface of each inner glass chamber [4].

- Attach Membrane: Firmly cover the holes on the outer side of each inner chamber with a 0.22 µm pore size polycarbonate membrane filter. Use a non-toxic, waterproof glue (e.g., CR glue) to ensure a complete seal, preventing cell exchange but allowing molecular diffusion [4].

- Sterilize Apparatus: Place the entire assembled apparatus (outer chamber and membrane-sealed inner chambers) in a laminar flow hood. Sterilize all surfaces with 75% (v/v) ethanol. Rinse thoroughly with particle-free molecular grade water. Dry and then expose to UV light for 12 hours to achieve complete sterilization [4] [27].

Media Preparation

- Prepare Artificial Seawater (ASW) Base: Prepare the ASW solution with the following composition per liter [4] [8]:

- NaCl: 26.0 g

- MgCl₂·6H₂O: 5.0 g

- CaCl₂·2H₂O: 1.4 g

- Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„: 4.0 g

- NHâ‚„Cl: 0.3 g

- KHâ‚‚POâ‚„: 0.1 g

- KCl: 0.5 g

- Trace element mixture: 1.0 mL

- 1 mol/L NaHCO₃ solution: 30.0 mL

- Vitamin mixture: 1.0 mL

- Thiamine solution: 1.0 mL

- Vitamin Bâ‚â‚‚ solution: 1.0 mL

- Prepare Enrichment Media: Prepare the three low-nutrient enrichment media by supplementing the ASW base [4] [8]:

- Lig-medium: Add 0.5% (w/v) alkali-lignin.

- St-medium: Add 0.5% (w/v) starch.

- ASW-medium: Use the ASW base without additional carbon sources.

- Prepare Sub-cultivation Media: Prepare solid media plates using 50% diluted marine 2216E and R2A agars, solidified with 1.5% agar [4] [8].

Experimental Setup and Inoculation

- Place Inner Chambers: Position the three sterile inner chambers inside the sterile outer chamber.

- Fill Outer Chamber: Add 75 g of the marine sediment sample mixed with 15 L of ASW-medium into the outer chamber. This creates the natural environmental context [4].

- Inoculate Inner Chambers: To each of the three inner chambers, add 0.25 g of the same marine sediment sample along with 500 mL of one of the three different enrichment media (Lig-, St-, and ASW-medium), assigning one medium type per chamber [4].

- Seal the Apparatus: Tightly cover the openings of the inner chambers with their glass lids. Seal the outer chamber with a glass cover sheet to prevent contamination [4].

Incubation and Monitoring

- Incubate: Transfer the entire microbial aquarium to an incubator and maintain at 25°C for 4 weeks [4].

- Agitate: Activate the electric rotator in the outer chamber for continuous, gentle homogenization of the sediment slurry. Manually stir the contents of each inner chamber with a sterile pipette at 72-hour intervals [4].

Post-Incubation Processing and Isolation

- Sample the Inner Chambers: After the 4-week incubation, aseptically collect samples from each inner chamber.

- Generate Serial Dilutions: Perform serial dilutions of the samples in sterile normal saline or a suitable buffer.

- Plate for Isolation: Spread plate 100 µL aliquots of the dilutions onto the 50% diluted marine 2216E and R2A agar plates.

- Incubate Plates: Incubate the agar plates aerobically at 25°C for up to 4 weeks, monitoring periodically for colony formation [4] [27].

- Purify Isolates: Randomly pick resulting colonies and perform repeated sub-culturing on fresh agar plates until pure isolates are obtained.

Expected Outcomes and Data Analysis

The success of the DICA protocol is evaluated by the diversity and novelty of the isolated bacterial strains, typically through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis [4] [27]. The quantitative results from a foundational study demonstrate the superior performance of DICA compared to the Traditional Cultivation Approach (TCA).

Table 2: Comparative Performance of DICA vs. Traditional Cultivation

| Cultivation Metric | DICA (Diffusion-Based) | Traditional Approach (TCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Isolates Recovered | 196 | 165 |

| Previously Uncultured Taxa | 115 | 20 |

| Novelty Ratio | 58% (115/196) | 12% (20/165) |

| Novelty Level (Genus/Family) | 39 at genus level, 4 at family level | All at species level only |

| Phylogenetic Diversity (Classes) | 12 different classes | 6 classes |

| Representation of Rare Phyla | Successful cultivation of Verrucomicrobiota and Balneolota | Primarily Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota |

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key procedural stages of the DICA protocol.

Applications in Drug Discovery