Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation in Coastal Sediments: Microbial Mechanisms, Environmental Drivers, and Biogeochemical Significance

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is a critical microbial process responsible for significant nitrogen loss in coastal ecosystems, converting reactive nitrogen into inert dinitrogen gas and thereby mitigating eutrophication.

Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation in Coastal Sediments: Microbial Mechanisms, Environmental Drivers, and Biogeochemical Significance

Abstract

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is a critical microbial process responsible for significant nitrogen loss in coastal ecosystems, converting reactive nitrogen into inert dinitrogen gas and thereby mitigating eutrophication. This article synthesizes current research on the foundational microbiology, novel pathways like manganammox, and key genera such as Candidatus Scalindua and Brocadia. It explores advanced methodological approaches for quantifying rates, examines the complex ecological interactions between anammox and denitrifying bacteria, and addresses challenges in process optimization. Through comparative analysis of diverse coastal environments, we evaluate the relative contributions of anammox to net nitrogen loss and its response to global change, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and environmental professionals.

Unveiling the Anammox Process: From Microbial Core to Global Significance

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is a microbially mediated process that constitutes a key sink for fixed nitrogen in global biogeochemical cycles, particularly in coastal marine sediments [1] [2]. This process, performed by specialized bacteria within the phylum Planctomycetota, converts ammonium and nitrite directly into dinitrogen gas under anoxic conditions [3] [2]. The anammox reaction is a unique form of chemolithoautotrophic metabolism that provides a significant ecological service by removing bioavailable nitrogen from aquatic ecosystems, thereby helping to mitigate eutrophication resulting from anthropogenic nitrogen inputs [1] [4]. Understanding the precise stoichiometry and energetics of this reaction is fundamental for quantifying its contribution to nitrogen losses in coastal sediments and for harnessing its potential in wastewater treatment technologies [5] [6]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the anammox biochemical reaction, with a specific focus on its stoichiometric relationships, thermodynamic properties, and the enzymatic machinery that facilitates this ecologically critical process.

Core Reaction Stoichiometry and Energetics

The anammox process is a redox comproportionation where ammonium serves as the electron donor and nitrite as the electron acceptor. The widely accepted stoichiometry, first established by Strous et al. (1998) and confirmed by subsequent studies, is as follows [5] [3] [2]:

NH4+ + 1.32 NO2- + 0.066 HCO3- + 0.13 H+ → 1.02 N2 + 0.26 NO3- + 0.066 CH2O0.5N0.15 + 2.03 H2O

This overall reaction represents the net result of catabolic energy generation and anabolic carbon fixation. The standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°') for this overall process is approximately -357 kJ/mol, making it thermodynamically favorable [3] [2]. A slightly revised stoichiometry was later proposed by Lotti et al. (2014) based on kinetic experiments and elemental analysis [5]:

1 NH4+ + 1.146 NO2- + 0.071 HCO3- + 0.057 H+ → 0.986 N2 + 0.161 NO3- + 0.071 CH1.74O0.31N0.20 + 2.002 H2O

Table 1: Comparison of Anammox Stoichiometric Coefficients

| Component | Strous et al. (1998) Stoichiometry | Lotti et al. (2014) Revised Stoichiometry |

|---|---|---|

| NH4+ | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| NO2- | 1.32 | 1.15 |

| HCO3- | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| H+ | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| N2 | 1.02 | 0.99 |

| NO3- | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| Biomass | 0.07 CH2O0.5N0.15 | 0.07 CH1.74O0.31N0.20 |

| H2O | 2.03 | 2.00 |

Energetic Considerations

The anammox process consists of two coupled partial reactions: the energy-generating catabolic reaction and the energy-consuming anabolic reaction for carbon fixation [3]. The catabolic reaction alone:

NH4+ + NO2- → N2 + 2H2O

has a ΔG°' of -357 kJ/mol, which provides the energetic drive for the process [3]. The nitrate produced (0.26 mol per mol NH4+ consumed) results from the oxidation of nitrite to generate reducing equivalents (electrons) necessary for carbon fixation [6]. This partial reaction:

0.27 NO2- + 0.066 HCO3- → 0.26 NO3- + 0.066 CH2O0.5N0.15

is endergonic with a ΔG°' of +82 kJ/mol and is driven by the energy released from the catabolic reaction [3]. The overall favorable thermodynamics enable anammox bacteria to thrive in various anoxic environments, including coastal sediments where they contribute significantly to nitrogen removal.

Biochemical Mechanism and Key Enzymes

Metabolic Pathway

The anammox catabolism occurs within a specialized organelle called the anammoxosome, which is surrounded by membrane lipids known as ladderanes that limit the diffusion of toxic intermediates [2]. The current model of the anammox biochemical pathway involves three coupled redox reactions with nitric oxide (NO) and hydrazine (N2H4) as intermediates [6] [3] [2]:

Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide: Catalyzed by nitrite reductase (Nir) NO2- + 2H+ + e- → NO + H2O (E0' = +0.38 V)

Condensation of ammonium and NO to form hydrazine: Catalyzed by hydrazine synthase (HZS) NO + NH4+ + 2H+ + 3e- → N2H4 + H2O (E0' = +0.06 V)

Oxidation of hydrazine to dinitrogen gas: Catalyzed by hydrazine dehydrogenase (HDH) N2H4 → N2 + 4H+ + 4e- (E0' = -0.75 V)

The electrons generated from hydrazine oxidation (step 3) are used to drive the initial reduction of nitrite to NO (step 1), creating a cyclic electron flow [6]. Additionally, some electrons are diverted for carbon fixation, which requires supplemental oxidation of nitrite to nitrate:

- Nitrite oxidation to nitrate: Catalyzed by nitrite oxidoreductase (NXR) NO2- + H2O → NO3- + 2H+ + 2e- (E0' = +0.43 V)

This final reaction replenishes electrons withdrawn from the quinone pool for biosynthetic purposes, explaining the nitrate byproduct in the overall stoichiometry [6].

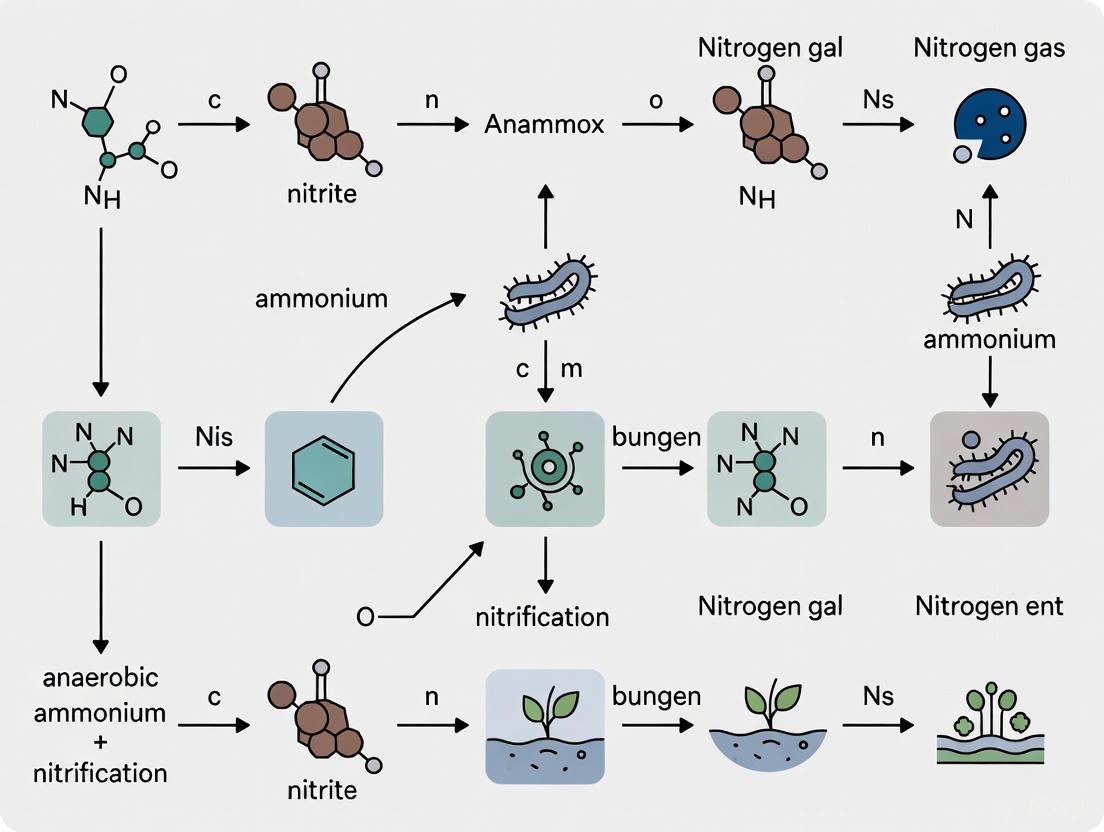

Diagram 1: Anammox Metabolic Pathway in the Anammoxosome

Role of Trace Hydrazine

Research has demonstrated that adding trace amounts of hydrazine can enhance the anammox process by increasing the yield of anammox bacteria and reducing nitrate production [5]. The kinetic parameters for hydrazine utilization were determined to be:

- Maximum specific substrate utilization rate: 25.09 mg N/g VSS/d

- Half-saturation constant: 10.42 mg N/L

- Inhibition constant: 1393.88 mg N/L

This enhancement occurs because the oxidation of externally added hydrazine partly substitutes for the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate for generating electrons required for cellular synthesis [5].

Anammox in Coastal Sediment Environments

Ecological Significance

In coastal sediments, anammox represents a crucial mechanism for nitrogen removal, working in concert with denitrification to convert reactive nitrogen into inert N2 gas [1]. Global measurements indicate that anammox can contribute 24-67% of total N2 production in continental shelf sediments [2], with some studies reporting contributions of up to 50% in specific marine ecosystems [4]. A recent global database of actual nitrogen loss rates documented through intact core incubations reported 255 measurements specifically for anammox across various coastal and marine systems [1]. The process is particularly significant in coastal regions receiving high anthropogenic nitrogen inputs, where it helps mitigate eutrophication effects [7] [1].

Microbial Community Structure

Molecular analyses of coastal sediments have revealed distinct spatial distribution patterns of anammox bacteria across different estuaries along the Chinese coastline [7] [8]. The predominant anammox genus in marine environments is Candidatus Scalindua, while Candidatus Brocadia and Candidatus Kuenenia are more abundant in estuarine sediments [7] [8]. Recent research has highlighted the critical ecological roles of rare species in maintaining the stability and function of anammox bacterial communities in coastal sediments, with these low-abundance taxa being more susceptible to dispersal limitations and environmental selection than their abundant counterparts [7] [8].

Table 2: Anammox Bacterial Distribution in Coastal Sediments

| Location | Predominant Genera | Species Richness | Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| South China Sea (SCS) | Candidatus Scalindua | Lowest Shannon diversity | Marine conditions, lower ammonium |

| Jiulong River Estuary (JLE) | Candidatus Brocadia, Candidatus Kuenenia | Highest Shannon diversity | Higher ammonium concentration |

| Changjiang Estuary (CJE) | Mixed community | Highest species richness | Estuarine gradient conditions |

| Oujiang Estuary (OJE) | Transitional community | Moderate diversity | Intermediate conditions |

Alternative Electron Acceptors

Beyond the conventional anammox process using nitrite, recent evidence indicates that anammox bacteria in coastal sediments can utilize alternative electron acceptors. One significant discovery is the manganammox process, where Mn(IV)-oxide serves as the terminal electron acceptor [4]:

2NH4+ + 3MnO2 + 4H+ → 3Mn2+ + N2 + 6H2O (ΔG°' = -552.9 kJ/mol)

This reaction is thermodynamically more favorable than conventional anammox and has been documented in coastal sediments from Baja California, where it demonstrated a nitrogen loss rate of 4.2 ± 0.4 μg ³â°N2/g-day - 17-fold higher than the feammox process (anaerobic ammonium oxidation linked to Fe(III) reduction) measured in the same sediments [4]. Several clades of Desulfobacterota have been identified as potential microorganisms catalyzing the manganammox process [4].

Experimental Methodologies

Stoichiometry Determination

The precise stoichiometry of the anammox process has been established through carefully controlled chemostat experiments and titration methods [5]. Key methodological approaches include:

Fixed-endpoint titration: Used to measure proton (H+) consumption during the anammox reaction, providing critical data for stoichiometric calculations [5].

Mass balancing: Tracking changes in substrates (NH4+, NO2-) and products (N2, NO3-) over time in closed systems, allowing for the calculation of stoichiometric coefficients [5] [2].

Isotope pairing technique (IPT): Using ¹âµN-labeled substrates (e.g., ¹âµNH4+ with ¹â´NO2- or vice versa) to distinguish N2 produced specifically from anammox versus denitrification in environmental samples [1].

Intact core incubations: Maintaining the natural structure of sediment cores during laboratory incubations to preserve the natural gradients of substrates and redox conditions, thereby providing more ecologically relevant rate measurements [1].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Anammox Stoichiometry

Molecular Detection Methods

Characterizing anammox bacterial communities in coastal sediments involves several molecular techniques:

DNA extraction: Using commercial kits (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for soil) to extract total community DNA from sediment samples [7] [9].

PCR amplification: Employing anammox-specific primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., Brod541F/Amx820R) or functional genes such as hzo (hydrazine oxidase) [7] [9].

High-throughput sequencing: Utilizing platforms such as Illumina to sequence amplified genes, followed by bioinformatic analysis using tools like QIIME 2 to determine microbial diversity and community structure [7].

Phylogenetic analysis: Constructing phylogenetic trees based on aligned sequences using software such as MEGA to determine evolutionary relationships among anammox bacteria [9].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Quantifying anammox bacterial abundance using specific gene markers [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Anammox Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ¹âµN-labeled ammonium (¹âµNHâ‚„âº) | Isotope pairing technique to quantify anammox rates | >98% atomic enrichment; used at environmentally relevant concentrations (μM range) |

| Sodium nitrite (NaNOâ‚‚) | Anammox substrate | Anoxic stock solutions; typical concentration range: 10-500 mg N/L |

| Hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) | Intermediate studies and process enhancement | Trace additions (kinetic parameters: Ks = 10.42 mg N/L) |

| FastDNA SPIN Kit | DNA extraction from sediment samples | Optimized for difficult environmental matrices |

| Anammox-specific primers | Molecular detection of anammox bacteria | Brod541F/Amx820R for 16S rRNA gene; hzo gene primers for functional detection |

| Vernadite (δ-MnO₂) | Manganammox studies | Nano-crystal size ~15 Å; electron acceptor in alternative anammox |

| HCO₃â»/COâ‚‚ source | Carbon source for anammox growth | Typically NaHCO₃; 0.066 mol per mol NH₄⺠consumed |

| Resazurin | Redox indicator for anoxic conditions | Visual confirmation of anaerobic conditions |

Factors Influencing Stoichiometry and Energetics

Environmental Conditions

The stoichiometry and energetic efficiency of the anammox process are influenced by various environmental factors prevalent in coastal sediments:

Temperature: Anammox activity has been documented across a wide temperature range from 20°C to 85°C, with optimal activity typically between 20°C and 43°C [9] [2]. However, specialized populations exist in thermophilic environments, including oil reservoirs (55-75°C) and hydrothermal vents (60-85°C) [9] [2].

pH: The anammox process consumes protons (H+), with stoichiometric coefficients ranging from 0.057 to 0.13 mol H+ per mol NH4+ consumed [5]. This proton consumption can influence local pH conditions in sediments.

Organic carbon: While anammox bacteria are autotrophic, the presence of organic matter can influence the competitive dynamics between anammox and heterotrophic denitrifiers in coastal sediments [6] [3].

Heavy metals: Ionic forms of heavy metals (e.g., Cu²âº, Zn²âº) can inhibit anammox activity, with Cu²⺠causing up to 85% decrease in specific anammox activity [10]. Nanoparticulate forms generally show less inhibition than ionic forms [10].

Kinetic Parameters

Understanding the kinetics of the anammox process is essential for modeling its contribution to nitrogen cycling in coastal sediments. Key kinetic parameters include:

- Maximum specific substrate utilization rate: Ranges from 25.09 mg N/g VSS/d for hydrazine to higher values for the overall process [5]

- Half-saturation constant (Ks): Typically in the sub-micromolar range, reflecting the high affinity of anammox bacteria for their substrates [2]

- Inhibition constants: For various potential inhibitors including substrates (NO2-), heavy metals, and other environmental toxins [5] [10]

The Monod equation, Haldane model, and pseudo-first order reaction models have all been applied to describe the kinetics of the anammox process under different conditions [5].

The anammoxosome is a unique and defining intracellular compartment found in anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria, representing a remarkable example of prokaryotic cellular complexity. This specialized organelle is the exclusive site of the energy metabolism that converts ammonium and nitrite into dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚), a process of critical importance to the global nitrogen cycle [11] [12]. Anammox bacteria belong to the phylum Planctomycetes and perform the anammox process under anoxic conditions, making substantial contributions to nitrogen loss in various environments, particularly in coastal and marine sediments [13] [14].

The ecological significance of the anammox process has been extensively documented in estuarine and coastal sediments, where it can contribute substantially to nitrogen removal. Studies in Chinese estuaries, including the Changjiang, Oujiang, and Jiulong River Estuaries, have revealed that anammox bacterial communities, particularly those dominated by genera like Candidatus Scalindua, play crucial roles in nitrogen cycling [13]. Similarly, research in the Indus Estuary has demonstrated that anammox bacteria contribute approximately 21.9% to total nitrogen loss on average [15]. Beyond its environmental significance, the anammoxosome has recently attracted attention for its potential applications in biotechnology and medicine, particularly due to its unique ladderane lipid membrane [11].

This review provides a comprehensive examination of the anammoxosome, focusing on its structural properties, biochemical functions, and ecological roles. We present detailed experimental protocols for studying this unique compartment and analyze quantitative data on its distribution and activity across different environments, with particular emphasis on coastal sediment ecosystems.

Structural and Biochemical Characteristics of the Anammoxosome

Unique Ladderane Lipid Membrane

The most distinctive structural feature of the anammoxosome is its membrane, composed of ladderane lipids. These remarkable molecules consist of three to five concatenated cyclobutane rings with unusual ladder-like structures [11]. The ladderane lipids form a dense and exceptionally impermeable membrane that serves critical physiological functions:

- Containment of toxic intermediates: The anammox process generates highly reactive and toxic intermediates, including hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„). The ladderane membrane acts as a barrier, preventing the diffusion of these compounds into the cytoplasm and protecting other cellular components [12].

- Maintenance of proton gradients: The low permeability of the ladderane membrane enables the establishment and maintenance of proton gradients across the anammoxosome membrane, which is essential for energy conservation through ATP synthesis [11].

- Structural stability: The unique arrangement of cyclobutane rings provides structural rigidity to the membrane, potentially contributing to the overall stability of the anammoxosome compartment [11].

Recent research has explored the biotechnological applications of ladderane lipids, particularly in the creation of artificial liposomes for drug delivery. Studies have demonstrated that liposomes incorporating ladderane lipids exhibit increased colloidal stability at elevated concentrations compared to those made solely of conventional phospholipids [11].

Anammox Metabolic Pathway and Key Enzymes

The anammoxosome houses the complete enzymatic machinery for the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium, a process that involves multiple steps and specialized enzymes:

- Nitrite reduction: Nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») is reduced to nitric oxide (NO) by the enzyme nitrite reductase (NirS).

- Hydrazine synthesis: Ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) and nitric oxide (NO) are condensed to form hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) by hydrazine synthase (HZS).

- Hydrazine oxidation: Hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) is oxidized to dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) by hydrazine dehydrogenase (HDH) [12].

The overall stoichiometry of the anammox process can be represented by the following equation: NH₄⺠+ 1.32 NOâ‚‚â» + 0.066 HCO₃⻠+ 0.13 H⺠→ 1.02 Nâ‚‚ + 0.26 NO₃⻠+ 0.066 CHâ‚‚Oâ‚€.â‚…Nâ‚€.â‚â‚… + 2.03 Hâ‚‚O [16]

All these catabolic reactions occur within the anammoxosome, generating a proton gradient across the anammoxosome membrane that drives ATP synthesis [12]. This compartmentalization of energy metabolism is unusual among prokaryotes and represents a significant evolutionary adaptation.

Figure 1: The anammox metabolic pathway localized within the anammoxosome compartment. Key enzymes catalyze the step-wise conversion of ammonium and nitrite to dinitrogen gas, with hydrazine as a toxic intermediate contained by the ladderane membrane. Notably, the pathway bypasses nitrous oxide production, unlike denitrification.

Research Methodologies for Anammoxosome Studies

Anammoxosome Isolation Protocol

The isolation of intact anammoxosomes is crucial for detailed biochemical and structural studies. Recent methodological advances have improved the efficiency of this process, particularly for aggregate cultures that were previously challenging to work with. The following protocol, adapted from studies on Candidatus Brocadia sapporoensis, provides a reliable approach for anammoxosome isolation [11]:

Sample Preparation:

- Start with an aggregated anammox biomass cultivated in a fed-batch reactor under anoxic conditions.

- Maintain the reactor at 30°C and pH 7.2, with continuous sparging using a CO₂/N₂ mixture (5%/95%) to ensure anoxic conditions.

- Feed the reactor with a synthetic substrate containing ammonium chloride and sodium nitrite in a 1:1 molar ratio, along with essential minerals and trace elements.

Isolation Procedure:

- Cell disruption: Gently disrupt the aggregated biomass to release intracellular components while preserving anammoxosome integrity.

- Enzymatic treatment: Apply a cocktail of enzymes including cellulase Onozuka R-10 and Macerozyme R-10 to degrade the extrapolymeric substances (EPS) matrix that surrounds anammox cells in aggregates.

- Extended EDTA treatment: Prolong the application of EDTA to enhance the disruption of the EPS and cell walls.

- Differential centrifugation: Perform sequential centrifugation steps to separate anammoxosomes from other cellular debris.

- Sucrose density gradient centrifugation: Replace traditional Percoll with a sucrose gradient for better separation efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Layer the sample on a discontinuous sucrose gradient and centrifuge at high speed.

- Anammoxosome collection: Carefully collect the anammoxosome-rich layer from the gradient and wash to remove residual sucrose.

Validation:

- Confirm the success of isolation through transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which should reveal intact anammoxosomes with characteristic membrane structures.

- Verify the presence of ladderane lipids using lipid extraction and analysis techniques.

This enhanced protocol efficiently removes EPS and other debris, yielding a purified fraction of anammoxosomes suitable for further analysis [11].

Molecular Detection of Anammox Bacteria

The study of anammox bacteria in environmental samples typically relies on molecular techniques targeting specific gene markers:

DNA Extraction:

- Use the FastDNA SPIN Kit for soil or similar protocols to extract genomic DNA from sediment samples.

- Quantify DNA concentration and purity using fluorometric methods and spectrophotometry.

PCR Amplification:

- Amplify the anammox bacterial 16S rRNA gene using specific primers such as Brod541F and Amx820R.

- Perform reactions with 35 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 45 s), annealing (56°C, 30 s), and extension (72°C, 50 s).

High-Throughput Sequencing:

- Sequence amplicons using platforms such as Illumina.

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, chimera removal, and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering at 97-98% similarity.

- Classify sequences against specialized anammox bacteria databases [13].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Quantify anammox bacterial abundance using primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene or functional markers like hydrazine synthase (hzsB).

- Perform reactions in triplicate with appropriate standard curves for absolute quantification [17] [15].

Metagenomic Analysis:

- Sequence total community DNA to recover metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) of anammox bacteria.

- Assess genome completeness and contamination using single-copy marker genes.

- Annotate genes involved in the anammox metabolism, particularly those encoding key enzymes [18].

Activity Measurements Using Isotope Tracing

The anammox process can be quantified in environmental samples and enrichment cultures using ¹âµN isotope tracing techniques:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect intact sediment cores or anammox biomass and pre-incubate under in situ conditions to stabilize metabolic activity.

- Prepare parallel samples with ¹âµN-labeled ammonium (¹âµNHâ‚„âº) or ¹âµN-labeled nitrite (¹âµNOâ‚‚â»).

Incubation and Analysis:

- Incubate samples anaerobically in gas-tight vials for specified periods.

- Terminate reactions by adding appropriate preservatives.

- Analyze the produced Nâ‚‚ gases for ²â¹Nâ‚‚ and ³â°Nâ‚‚ using gas chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

- Calculate anammox rates based on the production of ²â¹Nâ‚‚ from ¹âµNH₄⺠and ¹â´NOâ‚‚â», or ³â°Nâ‚‚ from ¹âµNH₄⺠and ¹âµNOâ‚‚â» [14] [15].

This sensitive method allows researchers to distinguish anammox from denitrification and quantify their respective contributions to Nâ‚‚ production in environmental samples.

Ecological Distribution and Activity in Coastal Sediments

Diversity and Community Composition

Anammox bacteria exhibit distinct distribution patterns across different coastal environments, with community composition strongly influenced by environmental factors. The table below summarizes the diversity and abundance of anammox bacteria in various estuarine and coastal sediments:

Table 1: Anammox Bacterial Diversity and Abundance in Coastal Sediments

| Location | Dominant Genera | Abundance (16S rRNA gene copies/g) | Key Environmental Drivers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiulong River Estuary | Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Kuenenia | Not specified | Ammonium concentration | [13] |

| South China Sea | Ca. Scalindua | Not specified | Dispersal limitation | [13] |

| Hangzhou Bay | Ca. Scalindua, Ca. Jettenia, Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Kuenenia, Ca. Anammoxoglobus | 2.34×10ⵠ- 9.22×10ⵠ| Salinity, depth, pH | [17] |

| Indus Estuary | Ca. Kuenenia, Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Scalindua, Ca. Jettenia | 1.64×10ⶠ- 8.21×10⸠| Temperature, sediment sulfide, Fe(II) | [15] |

| Global Inland Waters | Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Kuenenia | 3.1×10ⴠ- 3.3×10ⷠcopies/g | Moisture content, organic matter | [14] [19] |

Recent studies have expanded the known diversity of anammox bacteria with the discovery of novel lineages. A newly proposed family, Candidatus Bathyanammoxibiaceae, represents a deep-branching lineage within the order Candidatus Brocadiales. Members of this family contain the genetic potential for anammox metabolism and have been detected in both marine and terrestrial environments, suggesting that the diversity and ecological distribution of anammox bacteria may be broader than previously recognized [18].

Environmental Controls on Anammox Activity

The activity of anammox bacteria in coastal sediments is regulated by a complex interplay of environmental factors:

Salinity: Anammox bacteria exhibit niche partitioning along salinity gradients. The genus Candidatus Scalindua typically dominates in marine environments, while Candidatus Brocadia and Candidatus Kuenenia are more abundant in estuarine and low-salinity regions [13] [15]. Salinity influences the community composition and activity of anammox bacteria, with different genera showing distinct salinity optima.

Organic Matter: The availability of organic carbon indirectly affects anammox bacteria by influencing the activity of heterotrophic denitrifiers that compete for nitrite. However, high concentrations of organic matter can inhibit anammox activity, as observed in continuous acetate addition experiments that reduced the abundance of Candidatus Kuenenia by 8.00% and its activity by 66.80% [16].

Temperature: Anammox bacteria are sensitive to temperature fluctuations, which directly affect their metabolic rates and growth. Temperature optima vary among different species, but generally fall within the mesophilic range (20-40°C). A decline in temperature from 17.9°C to 15.1°C resulted in decreased abundance of anammox bacteria, with Candidatus Brocadia declining from 4.30% to 1.80% and Candidatus Kuenenia from 0.25% to 0.03% of the microbial community [16].

Dissolved Oxygen: Anammox bacteria are strictly anaerobic and sensitive to oxygen exposure. Increasing dissolved oxygen from 0.3 to 1.0 mg/L led to a sharp decline in the relative abundances of Candidatus Brocadia and Candidatus Kuenenia, decreasing from 1.63% and 1.32% to 0.83% and 0.09%, respectively [16].

Substrate Availability: The anammox process requires both ammonium and nitrite as substrates. The concentration of these compounds strongly influences anammox activity, with inhibitory effects observed at high concentrations. The half-saturation constant (Kₛ) for ammonium is generally below 5 μM, while values for nitrite range from 0.2-0.3 μM for Candidatus Kuenenia to less than 5 μM for Candidatus Brocadia, giving anammox bacteria a competitive advantage in low-nutrient environments [14].

Table 2: Anammox Process Contributions to Nitrogen Loss in Different Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Anammox Rate Range | Contribution to N-loss | Primary Environmental Controls | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Sediments | 0.01 - 0.32 μmol N kgâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | Up to 21.9% (average) | Salinity, Fe(II), TOC | [15] |

| Global Inland Waters | 1.0 - 975.9 μmol N mâ»Â² hâ»Â¹ | 0.9 - 82.2% | Moisture content, NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â» | [14] [19] |

| Oxygen Minimum Zones | Not specified | Significant contribution | Nitrate, dissolved oxygen | [19] |

| Global Wetlands | Not specified | 2.0 Tg N yrâ»Â¹ (China) | Soil moisture content | [19] |

| Paddy Fields | Not specified | 32.0 Tg N yrâ»Â¹ (global) | Flooding duration, fertilizer input | [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Anammoxosome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Product References |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastDNA SPIN Kit | DNA extraction | Efficient lysis and purification of genomic DNA from complex matrices like sediments | [13] |

| Brod541F/Amx820R primers | PCR amplification | Specific detection of anammox bacterial 16S rRNA genes | [13] |

| Cellulase Onozuka R-10 | Anammoxosome isolation | Degrades cellulose in extrapolymeric substances (EPS) for better cell disruption | [11] |

| Macerozyme R-10 | Anammoxosome isolation | Digests plant cell walls, helpful for degrading complex EPS matrices | [11] |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme treatment | General protease for degrading protein components in EPS and cell walls | [11] |

| DNase I | Enzyme treatment | Degrades extracellular DNA in EPS matrices | [11] |

| Sucrose gradient | Density centrifugation | Separates anammoxosomes based on buoyant density; alternative to Percoll | [11] |

| ¹âµN-labeled ammonium/nitrite | Isotope tracing | Quantifying anammox rates through ¹âµN pairing technique | [14] [15] |

| Carlo-Erba EA 2100 analyzer | Elemental analysis | Measures organic carbon and nitrogen content in sediments | [13] |

| OX 50 oxygen microsensor | Microprofiling | High-resolution dissolved oxygen measurements in sediments | [13] |

| MYC degrader 1 (TFA) | MYC degrader 1 (TFA), MF:C34H32ClF6N5O5, MW:740.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PLK1/p38|A-IN-1 | PLK1/p38|A-IN-1 | Bench Chemicals |

Research Workflow and Experimental Design

Figure 2: Integrated research workflow for comprehensive anammoxosome studies, encompassing molecular ecology, activity measurements, and biochemical characterization.

The anammoxosome represents a remarkable example of prokaryotic subcellular compartmentalization, housing the complete enzymatic machinery for the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium. Its unique ladderane lipid membrane serves critical functions in containing toxic intermediates and maintaining proton gradients for energy conservation. In coastal sediments, anammox bacteria containing this specialized organelle contribute significantly to nitrogen removal, with their diversity, abundance, and activity shaped by complex interactions between environmental factors and ecological processes.

Future research on anammoxosomes should focus on several promising directions:

- Cultivation of novel lineages: The recent discovery of deep-branching anammox bacteria like Candidatus Bathyanammoxibiaceae highlights the need for improved cultivation strategies to isolate these novel lineages and characterize their anammosome structures [18].

- Biotechnological applications: The unique properties of ladderane lipids warrant further exploration for pharmaceutical applications, particularly in drug delivery systems where membrane stability is crucial [11].

- Integration of multi-omics approaches: Combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metaproteomics will provide comprehensive insights into the function and regulation of anammoxosomes in natural environments.

- Engineering applications: Optimizing anammox-based wastewater treatment systems requires better understanding of how environmental factors affect anammoxosome function and overall process efficiency [16].

As research methodologies continue to advance, particularly in the areas of single-cell analysis and high-resolution imaging, our understanding of the anammoxosome's structure-function relationships will deepen, potentially revealing new insights into prokaryotic cellular complexity and evolutionary biology.

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is a critical microbial process responsible for a significant portion of nitrogen loss in natural and engineered ecosystems. This whitepaper examines the niche partitioning of key anammox genera, focusing on the dominance of Candidatus Scalindua in marine environments compared to the prevalence of Candidatus Brocadia and Candidatus Kuenenia in estuarine and freshwater systems. Through a synthesis of genomic, molecular, and biogeochemical evidence, we elucidate the environmental drivers, metabolic adaptations, and competitive mechanisms underlying this distribution pattern. Understanding these distinctions is paramount for modeling global nitrogen fluxes and developing biotechnological applications for nitrogen removal from saline wastewaters.

The anammox process, the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium with nitrite as the electron acceptor to yield dinitrogen gas, represents a major pathway in the global nitrogen cycle [20]. This process is exclusively mediated by a monophyletic group of bacteria within the phylum Planctomycetes [21] [22]. Among the described anammox genera, a clear biogeographical pattern has emerged: the genus Scalindua is the primary and often sole representative in open marine ecosystems, while genera such as Brocadia and Kuenenia dominate freshwater and terrestrial systems, with estuarine environments representing a critical transitional zone where these communities mix and shift [23] [24] [25]. This distribution is not random but is governed by a complex interplay of environmental gradients, physiological constraints, and genomic adaptations. This technical guide delves into the mechanisms behind this niche differentiation, framing it within the broader context of anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the dynamic and environmentally critical realm of coastal sediments.

Ecological Distribution and Environmental Drivers

Estuarine and coastal sediments are hotspots for nitrogen cycling, where anammox can contribute substantially to the removal of fixed nitrogen. The community composition of anammox bacteria in these sediments is highly sensitive to key environmental variables.

Biogeographical Partitioning

The global distribution of anammox bacteria is primarily governed by salinity, which acts as a master filter selecting for specific genera [23] [24].

- Marine Environments: Open marine waters and sediments worldwide are dominated by members of the genus Scalindua [21] [22]. In the marine water columns and sediments of oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), Scalindua is responsible for up to 50% of total nitrogen loss [21] [23]. Its near-exclusive presence in these stable, saline habitats indicates a high degree of specialization.

- Freshwater and Estuarine Environments: In contrast, non-saline ecosystems, including wastewater treatment systems, freshwater lakes, and terrestrial soils, are primarily inhabited by the genera Brocadia, Kuenenia, Jettenia, and Anammoxoglobus [23] [24] [26]. Estuaries, characterized by steep salinity gradients, serve as natural laboratories to observe the transition between these communities. Studies in the Cape Fear River Estuary [25] and the Indus Estuary [15] have demonstrated a shift in community composition along the salinity gradient, with Scalindua abundance increasing with salinity and Brocadia/Kuenenia dominating the freshwater and low-salinity stations.

Table 1: Key Environmental Drivers of Anammox Bacterial Distribution

| Environmental Factor | Effect on Anammox Community | Key Genera Impacted |

|---|---|---|

| Salinity | Primary driver; determines community composition at a global scale. | Scalindua (high salinity); Brocadia/Kuenenia (low/no salinity) [15] [23] [25] |

| Temperature | Influences activity and community distribution. | All genera; distribution linked to temperature in estuaries [15] |

| Substrate Availability (NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â») | Affects bacterial abundance and anammox rates. | All genera; Scalindua has high-affinity transport systems [21] |

| Sediment Sulfide | Correlates with community distribution in estuaries. | All genera, particularly in sulfidic environments [15] |

| Organic Matter | Can inhibit anammox or favor heterotrophic denitrifiers. | All genera [15] |

Quantitative Community Analysis

Molecular studies using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing provide quantitative evidence for these distribution patterns. In the Indus Estuary, the abundance of anammox bacteria based on 16S rRNA gene copies varied between 1.64 × 10ⶠand 8.21 × 10⸠copies gâ»Â¹ of sediment [15]. Furthermore, a study of the Cape Fear River Estuary found that the highest anammox rate occurred at the site where Scalindua dominated and anammox bacterial abundance was highest [25]. In terrestrial ecosystems, while Scalindua can be detected, Kuenenia and Brocadia are the most common representatives, indicating a higher diversity of anammox bacteria in terrestrial than in marine ecosystems [26].

Genomic and Metabolic Adaptations

The distinct habitats of marine and non-marine anammox bacteria have driven specific genomic and metabolic adaptations that underpin their competitive fitness.

Core Anammox Metabolism

All anammox bacteria share a core metabolic pathway that occurs within a specialized, membrane-bound organelle called the anammoxosome [27] [22]. The pathway involves three key steps:

- Reduction of nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») to nitric oxide (NO) by a cdâ‚ nitrite reductase (NirS) [21] [27].

- Condensation of ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) and NO to hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) by hydrazine synthase (HzsAB) [21] [27].

- Oxidation of hydrazine to dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) by hydrazine oxidoreductase (HZO) [21] [27].

Energy conservation is proposed to occur via a chemiosmotic mechanism involving an electron transport chain located on the anammoxosome membrane [21].

Diagram 1: Core anammox metabolic pathway in the anammoxosome.

Specialized Adaptations of Scalindua

Comparative genomics of "Candidatus Scalindua profunda" and the freshwater "Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis" reveal significant genetic divergence, with approximately 2,000 genes in S. profunda not found in K. stuttgartiensis and a similar number unique to K. stuttgartiensis [21]. These genomic differences translate to key adaptive features for Scalindua:

- Adaptation to Substrate Limitation: The marine water column is characterized by low and stable concentrations of ammonium and nitrite. Scalindua possesses highly expressed ammonium, nitrite, and oligopeptide transport systems, allowing it to effectively scavenge substrates and other nutrients (e.g., amino acids) from a dilute environment [21].

- Versatile Carbon Metabolism: Scalindua has genetic pathways for the transport, oxidation, and assimilation of small organic compounds, potentially allowing for a more versatile lifestyle that supplements its primary chemolithoautotrophic metabolism [21]. This may provide a competitive advantage in the marine realm where resources are limited.

- Salinity Tolerance: The fundamental partitioning suggests fundamental physiological adaptations to high osmotic pressure, though the specific genetic mechanisms are still under investigation [23] [24].

Adaptations of Brocadia and Kuenenia

Freshwater anammox bacteria like Brocadia and Kuenenia thrive in environments with higher and more fluctuating substrate concentrations, such as wastewater treatment plants and estuaries with significant terrestrial input.

- Interaction with Flanking Community: In non-saline bioreactors, Brocadia and Kuenenia often coexist in syntrophy with bacteria from phyla like Chloroflexi and Ignavibacteriae [23] [24]. These flanking communities may perform critical functions such as reducing nitrate to nitrite, which is then used by the anammox bacteria, creating a cooperative metabolic network [24].

- Kinetic Characteristics: While kinetic data can vary, it is postulated that differences in substrate affinity and growth rates between genera contribute to their distribution, with freshwater species potentially being more competitive in high-substrate environments [23].

Table 2: Comparative Genomic and Physiological Features of Key Anammox Genera

| Feature | Scalindua (Marine) | Brocadia / Kuenenia (Freshwater/Estuarine) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Habitat | Marine water columns, sediments, OMZs [21] [22] | Freshwater sediments, wastewater treatment, soils [23] [26] |

| Genomic Distinctness | ~2000 unique genes not in K. stuttgartiensis [21] | ~2000 unique genes not in S. profunda [21] |

| Key Adaptations | High-affinity transport systems; use of organic compounds [21] | Syntrophy with nitrate-reducing community [23] [24] |

| Salinity Preference | High (Marine, ~3.5%) [23] [22] | Low/None (Freshwater) [23] |

| Tolerance to Oxygen | Inhibited by oxygen > 2 μM [22] | Inhibited by oxygen [20] |

Experimental Methodologies for Sediment Research

Research on anammox bacteria in coastal sediments relies on a combination of molecular techniques to detect the organisms and isotope tracer methods to quantify their activity.

Molecular Detection and Community Analysis

- DNA Extraction: Microbial biomass is first collected from sediment samples. Due to the slow growth of anammox bacteria and their often low abundance, efficient and unbiased DNA extraction is critical. The under-representation of anammox sequences in metagenomic studies can be caused by incomplete DNA extraction [21].

- PCR Amplification: Specific primer sets targeting the 16S rRNA gene or functional genes (e.g., hzsA) unique to anammox bacteria are used. A nested PCR approach is often employed to successfully detect anammox bacteria in all sediment samples, even when abundance is low [15].

- Community Analysis: After PCR amplification, several techniques are used:

- Cloning and Sequencing: Provides detailed information on the diversity and phylogenetic identity of anammox bacteria present [15] [25].

- Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (T-RFLP): A fingerprinting method used to rapidly analyze temporal and spatial variations in anammox community structure [25].

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Used to determine the abundance (gene copy number) of anammox bacteria in the sediment, which can be correlated with environmental parameters and process rates [15] [25].

Activity Measurements and Isotope Tracing

The contribution of anammox to total Nâ‚‚ production is quantified using stable isotope tracing.

- Incubation Setup: Sediment slurries or intact cores are incubated under strictly anoxic conditions with ¹âµN-labeled substrates (either ¹âµNH₄⺠or ¹âµNOâ‚‚â») [15] [25].

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): The production of labeled dinitrogen gas (²â¹Nâ‚‚ and ³â°Nâ‚‚) is measured over time using GC-MS.

- Rate Calculation: The anammox rate is calculated based on the production of ²â¹Nâ‚‚ from ¹âµNHâ‚„âº, as anammox produces Nâ‚‚ from one ¹âµN-atom and one ¹â´N-atom. Simultaneously, denitrification rates can be estimated from the production of ³â°Nâ‚‚ and ²â¹Nâ‚‚ [15]. Studies in the Indus Estuary reported potential anammox rates in the range of 0.01–0.32 μmol N kgâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ [15].

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for anammox community and activity analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Anammox Research in Sediments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specific PCR Primers | Amplification of anammox-specific 16S rRNA or functional genes (hzsA, hzo) for detection and diversity analysis. | Brocadia- or Scalindua-specific 16S rRNA primers; nested PCR primers for low-abundance samples [15] [25]. |

| ¹âµN-Labeled Substrates | Tracer for quantifying anammox activity and contribution to Nâ‚‚ production in incubation experiments. | ¹âµNH₄⺠(e.g., (¹âµNHâ‚„)â‚‚SOâ‚„) or ¹âµNOâ‚‚â»; used in isotope pairing techniques [15] [25]. |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Probes | Visual identification, enumeration, and spatial localization of anammox cells in sediment samples or biofilms. | Oligonucleotide probes targeting the 16S rRNA of specific anammox genera (e.g., Amx368 for most anammox bacteria, Sca1309 for Scalindua) [21]. |

| Metagenomic Assembly Kits | Preparation of high-quality DNA for sequencing to reconstruct genomes and analyze metabolic potential from complex sediment communities. | Used for community sequencing and assembly of genomes from enrichment cultures (e.g., for "Ca. Scalindua profunda") [21] [23]. |

| Membrane Filtration Systems | Biomass retention in enrichment cultures; concentration of cells from water samples for DNA extraction. | Critical for enriching slow-growing anammox bacteria in membrane bioreactors (MBRs) [21] [23]. |

| Hsd17B13-IN-57 | Hsd17B13-IN-57|HSD17B13 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Hsd17B13-IN-57 is a potent HSD17B13 inhibitor. It is for research use only, not for human, veterinary, or diagnostic use. |

| Icmt-IN-46 | Icmt-IN-46|ICMT Inhibitor|For Research Use | Icmt-IN-46 is a potent ICMT inhibitor for cancer research. It disrupts Ras membrane localization and function. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Implications for Research and Biotechnology

The niche differentiation between anammox genera has profound implications for both environmental science and environmental biotechnology.

- Global Nitrogen Modeling: The dominance of Scalindua in marine systems means that its activity and response to environmental change (e.g., expansion of OMZs due to climate change) must be accurately parameterized in global nitrogen cycle models [21].

- Biotechnological Applications: The discovery that Scalindua is uniquely adapted to saline environments signifies its potential application for treating nitrogen-rich saline wastewaters, such as those from seafood processing, aquaculture, and certain industrial processes [23] [24]. Inoculating bioreactors with marine anammox bacteria could avoid the need for costly dilution of saline wastewater.

- Functional Redundancy: Despite the phylogenetic differences between marine and freshwater anammox communities, there is functional redundancy in the nitrogen removal process. Both systems achieve the same goal—the conversion of fixed nitrogen to N₂ gas—through the core anammox metabolism, even if the flanking microbial communities that support them differ [24].

The partitioning of anammox bacterial genera along the marine-estuarine-freshwater continuum is a paradigm of microbial biogeography. Scalindua's dominance in the marine realm is underpinned by genomic adaptations for life in a stable, saline, and nutrient-poor environment, including sophisticated transport systems and metabolic versatility. In contrast, Brocadia and Kuenenia prevail in freshwater and estuarine systems where they interact with a syntrophic microbial network. This fundamental understanding, derived from advanced molecular and isotopic techniques, is critical for predicting the response of the nitrogen cycle to anthropogenic change and for harnessing the power of these unique microorganisms in sustainable wastewater treatment technologies. Future research, particularly leveraging long-read metagenomic sequencing to obtain high-quality genomes from complex environments, will continue to unveil the intricate details of their ecophysiology.

Within the framework of anaerobic ammonium oxidation research in coastal sediments, the discovery of novel pathways beyond the conventional anammox process represents a paradigm shift. For decades, anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrite reduction (anammox) was considered the primary biological process responsible for nitrogen loss in anoxic marine environments. However, emerging evidence now confirms that ammonium can be oxidized using a broader range of electron acceptors, particularly metals like manganese and iron [28]. These processes, termed manganammox (Mn-ANAMMOX) and feammox (Fe-ANAMMOX), constitute non-canonical anammox pathways that significantly expand our understanding of the nitrogen cycle in coastal ecosystems [29]. Their discovery challenges traditional nitrogen cycle models and reveals complex interconnections between nitrogen, manganese, and iron biogeochemical cycles. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of these novel pathways, their mechanisms, quantitative significance, and methodologies for their investigation in coastal sediment research.

Biochemical Foundations and Stoichiometry

Manganammox: Ammonium Oxidation Coupled to Mn(IV) Reduction

The manganammox process involves the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium coupled to the reduction of Mn(IV) oxides. The thermodynamically favorable complete oxidation to dinitrogen gas follows this stoichiometry [4]:

[2NH4^+ + 3MnO2 + 4H^+ \rightarrow 3Mn^{2+} + N2 + 6H2O \quad \Delta G°' = -552.9 \, KJ/mol]

Experimental studies with coastal sediments from San Quintin Bay (Mexico) demonstrated a ratio of ∆[Mn(II)]/∆[NHâ‚„âº] of 1.8, closely aligning with the theoretical stoichiometric value of 1.5 for the complete oxidation of ammonium to Nâ‚‚ [4]. The process can also proceed through partial oxidation pathways producing nitrite or nitrate, though the complete oxidation to Nâ‚‚ appears dominant in coastal systems [29].

Feammox: Ammonium Oxidation Coupled to Fe(III) Reduction

Feammox represents the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium linked to Fe(III) reduction, with three potential transformation pathways identified [30] [31]:

Complete oxidation to Nâ‚‚: [3Fe(OH)3 + 5H^+ + NH4^+ \rightarrow 3Fe^{2+} + 9H2O + 0.5N2 \quad \DeltarGm = -245 \, kJ/mol]

Partial oxidation to nitrite: [6Fe(OH)3 + 10H^+ + NH4^+ \rightarrow 6Fe^{2+} + 16H2O + NO2^-]

Partial oxidation to nitrate: [8Fe(OH)3 + 14H^+ + NH4^+ \rightarrow 8Fe^{2+} + 21H2O + NO3^-]

The complete oxidation to Nâ‚‚ is thermodynamically most favorable and dominates at neutral pH, while partial oxidation becomes more significant under acidic conditions [32].

Table 1: Comparative Stoichiometry and Energetics of Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation Pathways

| Process | Electron Acceptor | Stoichiometric Reaction | Energy Yield (ΔG°') |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Anammox | Nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») | NH₄⺠+ 1.32NOâ‚‚â» + 0.066HCO₃⻠+ 0.13H⺠→ 1.02Nâ‚‚ + 0.26NO₃⻠+ 0.06CHâ‚‚Oâ‚€.â‚…Nâ‚€.â‚â‚… + 2.03Hâ‚‚O | -275 kJ/mol [28] |

| Manganammox | Mn(IV) oxide | 2NH₄⺠+ 3MnO₂ + 4H⺠→ 3Mn²⺠+ N₂ + 6H₂O | -552.9 kJ/mol [4] |

| Feammox (N₂ pathway) | Fe(III) hydroxide | 3Fe(OH)₃ + 5H⺠+ NH₄⺠→ 3Fe²⺠+ 9H₂O + 0.5N₂ | -245 kJ/mol [32] |

Quantitative Significance in Coastal Sediments

Process Rates and Environmental Contributions

Recent quantitative assessments reveal both manganammox and feammox contribute significantly to nitrogen removal in coastal sediments:

Manganammox in San Quintin Bay sediments demonstrated a nitrogen loss rate of 4.2 ± 0.4 μg ³â°Nâ‚‚/g·day, approximately 17-fold higher than the feammox rate measured in the same sediments (0.24 ± 0.02 μg ³â°Nâ‚‚/g·day) [4].

Spatial distribution studies across a coastal lagoon system (Bahia de San Quintin) showed potential NC-anammox rates ranging from 0.04 to 0.71 μg N gâ»Â¹ dayâ»Â¹, with generally higher rates in vegetated sediments compared to adjacent bare sediments [29].

Integrated nitrogen loss attributed to these NC-anammox pathways in the investigated area was estimated at 32.3 ± 3.6 t N annually, accounting for 2.9-4.7% of the gross total import of reactive nitrogen from the ocean into Bahia de San Quintin [29].

In wastewater treatment systems designed to mimic these natural processes, feammox achieved ammonium removal efficiencies exceeding 95% under optimal conditions [30].

Comparative Performance in Engineered Systems

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Manganammox and Feammox in Natural and Engineered Systems

| System Type | Process | Electron Donor | Ammonium Removal Rate/Loading | Key Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Sediments (San Quintin Bay) | Manganammox | Vernadite (δ-MnOâ‚‚) | 4.2 ± 0.4 μg ³â°Nâ‚‚/g·day [4] | Bioavailable Mn(IV), organic carbon, presence of vegetation [29] |

| Coastal Sediments (San Quintin Bay) | Feammox | Fe(III) oxides | 0.24 ± 0.02 μg ³â°Nâ‚‚/g·day [4] | Bioavailable Fe(III), organic carbon, pH, redox potential [31] |

| SADA Bioreactor (Wastewater) | Feammox | Pyrite (FeS₂) | >95% removal efficiency [30] | Hydraulic retention time, NH₄⺠loading, Fe(III) availability [30] |

| SBR System (Saline Wastewater) | Marine Feammox | Fe(II) addition | 0.85 kg NHâ‚„âº/(m³·d) removal rate [33] | Salinity, temperature, Fe(II) concentration (optimal 25 mg/L) [33] |

Microbial Mechanisms and Key Microorganisms

Microbial Catalysts and Community Structure

The microbial communities driving these novel pathways represent diverse phylogenetic groups with distinct metabolic capabilities:

Manganammox-associated microorganisms in coastal sediments are primarily within the Desulfobacterota phylum, with several specific clades potentially responsible for the process [4]. These organisms likely possess the enzymatic machinery to simultaneously oxidize ammonium and reduce Mn(IV).

Feammox-performing communities are more diverse, including Geobacteraceae and Acidomicrobiaceae A6 as key dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria (DMRB) [29]. These iron-reducing bacteria have been identified as potential catalysts coupling their reductive dissimilatory iron metabolism with ammonium oxidation [31] [29].

Anammox bacteria (Brocadiales) themselves have demonstrated extracellular electron transfer (EET) capability, transferring electrons from ammonium oxidation to insoluble extracellular electron acceptors including electrodes and graphene oxide [34]. This suggests that some anammox bacteria may directly participate in metal-coupled ammonium oxidation.

In engineered feammox systems, Thiobacillus (for denitrification and sulfur oxidation) and Candidatus_Brocadia (for anammox and potentially feammox) have been identified as key genera [30].

Molecular and Metabolic Pathways

The metabolic pathways for manganammox and feammox differ fundamentally from conventional anammox:

Conventional anammox occurs in the anammoxosome through a specialized metabolism involving nitrite reduction to nitric oxide (NO), followed by the combination of NO and ammonium to form hydrazine (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„), which is then oxidized to Nâ‚‚ [28] [6]. This process generates electrons for carbon fixation through nitrite oxidation to nitrate.

EET-dependent anammox bypasses the need for nitrite, with anammox bacteria oxidizing ammonium to Nâ‚‚ via hydroxylamine (NHâ‚‚OH) as an intermediate while transferring electrons to extracellular acceptors [34]. This pathway involves cytochrome c proteins homologous to those in Geobacter and Shewanella species [34].

Metal-reducing bacteria likely facilitate feammox and manganammox through different mechanisms, potentially acting as intermediaries that link metal reduction to ammonium oxidation, though the exact biochemical pathways remain under investigation [29].

Diagram 1: Proposed biochemical pathways for Feammox and Manganammox processes showing ammonium oxidation coupled to metal reduction via extracellular electron transfer. Based on experimental evidence from [4] [34].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Core Experimental Approaches

Investigating manganammox and feammox in coastal sediments requires specialized methodological approaches:

Sediment Sampling and Core Processing

- Collect intact sediment cores using manual corers (e.g., acrylic cores) from representative locations including vegetated (seagrass) and non-vegetated areas [29].

- Process cores under anaerobic conditions (glove bag with Nâ‚‚ atmosphere) to maintain original redox conditions [4].

- Section cores at different depth intervals (typically 0-20 cm at 5 cm intervals) to resolve vertical stratification of processes [29].

- Determine basic sediment characteristics: granulometry, moisture content, pH, organic carbon content, and natural metal concentrations [29].

Anoxic Incubation Experiments

- Prepare serum bottles or vials with sediment slurries or intact core sections under strict anoxic conditions [4].

- Add appropriate electron acceptors: vernadite (δ-MnO₂) for manganammox studies [4] or Fe(III) compounds (Fe₂O₃, Fe(OH)₃, ferrihydrite) for feammox studies [31].

- Include controls without electron acceptors and abiotic controls (e.g., sterilized with gamma radiation or azide) to account for non-biological processes [4].

- Maintain anoxic conditions by repeatedly flushing headspace with helium or argon and using oxygen scavengers if necessary [4].

¹âµN Isotope-Tracing and Rate Measurements

- Add ¹âµN-labeled ammonium (¹âµNHâ‚„âº) to sediment incubations to track its transformation [4] [29].

- Measure produced ²â¹Nâ‚‚ and ³â°Nâ‚‚ over time using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [4] [29].

- Calculate process rates from the linear accumulation of ³â°Nâ‚‚ (from ¹âµNH₄⺠oxidation) over time, normalized to sediment dry weight [4].

- Parallel monitoring of metal reduction: Mn(II) production for manganammox [4] and Fe(II) production for feammox [31].

Microbial Community Analysis

- Extract DNA from sediment samples before and after incubations using commercial kits with modifications for sediment matrices [4] [29].

- Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Illumina MiSeq platform) to characterize overall bacterial community composition [4].

- Target functional genes for more specific analysis: dsrB for sulfate reducers, mtrC for metal reducers [4].

- Apply FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) with specific probes for anammox bacteria (Pla46, Amx368) to visualize abundance and distribution [34].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for investigating manganammox and feammox in coastal sediments, integrating geochemical and microbiological approaches. Based on methodologies from [4] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Manganammox and Feammox Investigations

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Acceptors | Vernadite (δ-MnO₂; nano-crystal size ~15 Å) [4] | Terminal electron acceptor for manganammox | High purity, specific surface area critical for reactivity |

| Fe(III) compounds: Fe₂O₃, Fe(OH)₃, ferrihydrite [31] | Terminal electron acceptor for feammox | Fe₂O₃ shows highest ammonium removal efficiency [31] | |

| Isotopic Tracers | ¹âµN-labeled ammonium (¹âµNHâ‚„âº) [4] [29] | Quantifying Nâ‚‚ production pathways | Enables distinction from other N-cycling processes |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials for Mn(II), Fe(II), NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â», NO₃⻠| Calibration of analytical instruments | Essential for accurate quantification of process rates |

| Molecular Biology | DNA extraction kits (adapted for sediments) [4] | Microbial community analysis | Must efficiently lyse diverse bacterial groups |

| PCR primers for 16S rRNA, functional genes [4] | Target gene amplification | Specificity for metal-reducing and anammox bacteria | |

| Process Monitoring | GC-MS with Precon unit [4] | ²â¹Nâ‚‚ and ³â°Nâ‚‚ quantification | High sensitivity required for sediment slurries |

| ICP-MS/AAS [4] | Metal (Mn, Fe) concentration | Distinguishes oxidation states where possible | |

| Actarit-d6 (sodium) | Actarit-d6 (sodium), MF:C10H10NNaO3, MW:221.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fluo-3FF (pentapotassium) | Fluo-3FF (pentapotassium), MF:C35H21Cl2F2K5N2O13, MW:981.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Environmental Controls and Co-factors

The occurrence and rates of manganammox and feammox in coastal sediments are governed by several key environmental factors:

Bioavailable metal oxides: The presence of microbiologically reducible Fe(III) and Mn(IV) is a primary prerequisite. Crystalline structure, surface area, and accessibility significantly influence process rates [4] [31].

Organic carbon content: Moderate organic matter supports metal-reducing bacterial communities, but excessive organic carbon may favor competing processes like denitrification or sulfate reduction [29].

Sediment characteristics: Seagrass vegetation enhances both feammox and manganammox rates by modifying sediment biogeochemistry through root exudates and oxygen release [29]. Sediment texture (silt vs. sand content) influences permeability and metal availability.

pH conditions: Near-neutral pH favors the complete oxidation of ammonium to Nâ‚‚ in feammox, while acidic conditions shift the pathway toward nitrite or nitrate production [32].

Salinity and temperature: These processes occur across diverse salinity regimes from freshwater to marine systems [33]. Temperature optima vary, with some marine feammox activity observed at temperatures as low as 15°C [33].

Competing electron acceptors: The presence of oxygen, nitrate, or sulfate may suppress metal reduction by supporting thermodynamically more favorable microbial processes [31].

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several critical knowledge gaps remain in understanding these novel pathways:

Genetic markers and biomarkers: Specific functional genes for feammox and manganammox remain unidentified, hindering the development of molecular detection tools [29].

Pure culture verification: No isolated pure cultures have been confirmed to perform these processes, limiting mechanistic studies [4].

Environmental significance quantification: The relative contribution of these pathways to total nitrogen removal across different coastal ecosystems remains poorly constrained [29].

Interspecies interactions: The potential synergistic relationships between metal-reducing bacteria and anammox bacteria in natural communities warrant further investigation [34].

Response to global change: How these processes will respond to anthropogenic pressures including nitrogen loading, climate change, and coastal development is essentially unknown.

Future research should prioritize isolating key microorganisms, identifying genetic markers, developing isotopic techniques to distinguish these pathways in complex systems, and integrating these processes into ecosystem models of coastal nitrogen cycling.

Manganammox and feammox represent scientifically significant novel pathways that expand our understanding of anaerobic ammonium oxidation in coastal sediments. These processes directly couple the nitrogen cycle with metal redox transformations, creating previously unrecognized sinks for reactive nitrogen. With manganammox rates exceeding feammox by an order of magnitude in some coastal systems, and both processes contributing measurably to total nitrogen removal, they demand consideration in coastal nitrogen budgets. The experimental methodologies outlined here provide a foundation for further investigation, while the identified research gaps highlight productive avenues for future study. As research progresses, these novel pathways may also inspire innovative biotechnological applications for wastewater treatment and environmental remediation.

Global Distribution and Database Synthesis of Actual Nitrogen Loss Rates

The global nitrogen cycle has been profoundly altered by human activities, leading to an overabundance of reactive nitrogen (Nr) in coastal and marine ecosystems. This Nr enrichment drives serious environmental issues including eutrophication, hypoxia, and harmful algal blooms [1]. Within this context, the microbial processes of denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) serve as critical natural filters. These processes permanently remove reactive nitrogen by converting it to inert dinitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚), thereby mitigating the adverse effects of excessive nitrogen inputs [1] [35].

Despite decades of research, studies on sedimentary nitrogen loss have typically been limited to local or regional scales. A comprehensive understanding of global patterns and the environmental drivers regulating these processes has remained elusive. This whitepaper synthesizes findings from a newly compiled global database of actual nitrogen loss rates, placing specific emphasis on the mechanisms and distribution of anammox in coastal sediments. It serves as a technical guide for researchers and professionals seeking to understand, quantify, and model these crucial biogeochemical pathways [1] [36].

Global Databases for Nitrogen Loss Rates

The recent compilation of a global database for actual nitrogen loss rates marks a significant advancement in the field. This dataset provides a standardized foundation for large-scale comparative studies and model parameterization.

- Core Dataset Features: The database, available via the Figshare repository, consolidates peer-reviewed measurements obtained exclusively from intact core incubations combined with 15N isotope pairing techniques. This methodological consistency ensures that the rates reflect near-natural conditions, preserving in-situ sediment gradients and structures. The database includes 473 measurements for total nitrogen loss, 466 for denitrification, and 255 for anammox, collected from 1996 to 2024 [1].

- Controlled Conditions: To enable valid cross-study comparisons, the database strictly incorporates measurements taken under dark conditions to avoid the influence of photosynthetic oxygen production, and at ambient oxygen concentrations, excluding experiments with meiofauna or antibiotic additions [1].

- Associated Environmental Variables: Beyond rate measurements, the database appends critical contextual data, including sediment organic carbon, C/N ratios, oxygen penetration depth, and water parameters such as salinity, depth, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and concentrations of ammonium and nitrate [1].

Spatial Distribution and Environmental Drivers

Analysis of the global database reveals distinct biogeographical patterns in nitrogen loss rates, which are largely governed by a suite of environmental factors.

Global Patterns of Denitrification and Anammox

Nitrogen loss processes exhibit significant spatial and temporal variability. Denitrification is generally the dominant pathway, but the contribution of anammox can be substantial and highly variable.

Table 1: Representative Nitrogen Loss Rates Across Coastal Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Total N Loss (µmol N mâ»Â² hâ»Â¹) | Denitrification (µmol N mâ»Â² hâ»Â¹) | Anammox (µmol N mâ»Â² hâ»Â¹) | Anammox Contribution (%) | Key Reference Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seagrass Meadow | High | 1317 ± 389 (mean ~34.9 mg N mâ»Â² dâ»Â¹) | 467 ± 128 (mean ~12.4 mg N mâ»Â² dâ»Â¹) | Up to ~26% | Central Red Sea [37] |

| Coastal Wetlands | Moderate to High | Not Specified | 1.8 - 10.4 µmol N kgâ»Â¹ dâ»Â¹ (potential) | 3.8 - 10.7% | China [35] |

| Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) | High | Not Specified | Not Specified | Major contributor | Global [19] |

Key Environmental Controls

The rates and relative importance of nitrogen loss pathways are regulated by a complex interplay of factors:

- Temperature: A master variable, temperature strongly influences microbial metabolism. Studies in the Red Sea and along the China coast show a clear positive correlation between temperature and both denitrification and anammox rates. This relationship suggests that forecasted warming could accelerate nitrogen removal from coastal sediments [37] [35].

- Organic Matter and Nutrient Availability: The availability of organic carbon fuels denitrification, while anammox, being autotrophic, is more dependent on the direct substrates ammonium and nitrite. In Red Sea seagrass sediments, anammox rates decreased with increasing organic matter, whereas Nâ‚‚ fixation increased [37]. In China's coastal wetlands, anammox rates correlated significantly with nitrite and ammonium concentrations [35].

- Oxygen and Redox Conditions: Dissolved oxygen (DO) is a primary control. Anammox requires strict anoxia, and its activity peaks in environments like OMZs, where nitrate and DO are key predictive factors [19]. In bioturbated sediments, oxygen dynamics directly influence the zones where these anaerobic processes can occur.

The following diagram illustrates the primary environmental factors controlling anaerobic nitrogen loss processes in coastal sediments and their interrelationships:

Emerging Pathways: Manganammox

Beyond conventional anammox, recent research has identified manganammox—anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to the reduction of Mn(IV)—as a novel and potentially important Nr sink in coastal sediments.

- Process Identification: Experimental evidence from coastal sediments in Baja California demonstrated simultaneous ammonium oxidation and Mn(II) production upon the addition of vernadite (δ-MnOâ‚‚). The measured Δ[Mn(II)]/Δ[NHâ‚„âº] ratio of 1.8 was remarkably close to the theoretical stoichiometric value of 1.5 for the manganammox reaction [4] [38].

- Quantitative Significance: Tracer analysis revealed a manganammox-associated nitrogen loss rate of 4.2 ± 0.4 μg ³â°Nâ‚‚/g-day, which was 17-fold higher than the rate linked to the feammox (Fe(III) reduction-coupled ammonium oxidation) process in the same sediments [4] [38].

- Microbial Catalysts: 16S rRNA gene sequencing identified several clades within the Desulfobacterota as potential microorganisms catalyzing the manganammox process, indicating a previously overlooked microbial consortium involved in the nitrogen cycle [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Accurate quantification of in-situ nitrogen loss rates relies on sophisticated and carefully controlled experimental approaches.

Standardized Measurement Techniques

The core database is built upon two primary methodological approaches:

- Intact Core Incubations with ¹âµN Tracer: This is the gold-standard method for quantifying actual nitrogen loss rates. Intact sediment cores are collected to preserve natural stratigraphy and redox gradients. They are incubated in the dark at near-in situ temperatures. The ¹âµN isotope pairing technique (IPT) involves introducing ¹âµN-labeled nitrate (¹âµNO₃â») or ammonium (¹âµNHâ‚„âº) into the core. The subsequent production of ²â¹Nâ‚‚ and ³â°Nâ‚‚ gases is measured over time using mass spectrometry, allowing for the calculation of denitrification and anammox rates [1] [35].

- Continuous-Flow Incubations: A variation where bottom water is continuously pumped over intact cores in a flow-through system. Inflow and outflow samples are collected after ¹âµN tracer addition to quantify process rates, providing a dynamic system that more closely mimics natural advection [1].

Workflow for Quantifying Nitrogen Loss

The following diagram outlines the standard experimental workflow for measuring nitrogen loss rates using intact core incubations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for conducting research on nitrogen loss processes in coastal sediments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ¹âµN-Labeled Compounds (e.g., K¹âµNO₃, (¹âµNHâ‚„)â‚‚SOâ‚„) | Tracer for quantifying process rates via isotope pairing; allows distinction between Nâ‚‚ sources. | Quantifying denitrification and anammox rates in intact core incubations [1] [35]. |

| Vernadite (δ-MnO₂) | Terminal electron acceptor to investigate the novel manganammox process. | Amending sediments to demonstrate Mn(IV)-coupled ammonium oxidation [4] [38]. |

| Microsensors (Oâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚S, Redox) | High-resolution measurement of chemical gradients in sediment cores at microscale. | Determining oxygen penetration depth and mapping redox zonation [37]. |

| Plastic Biofilm Media (e.g., Bee-cell 2000) | Provides high-surface-area support for biofilm growth in bioreactor studies. | Cultivating anammox bacteria in upflow anaerobic biofilm reactors [39]. |

| Trace Element Solutions (e.g., EDTA, FeSOâ‚„, ZnSOâ‚„, CoClâ‚‚) | Supplies essential micronutrients for the growth and metabolism of autotrophic bacteria. | Component of synthetic wastewater for maintaining anammox cultures [39]. |

| (3E,5E)-Octadien-2-one-13C2 | (3E,5E)-Octadien-2-one-13C2, MF:C8H12O, MW:126.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pseudouridine-O18 | Pseudouridine-O18, MF:C9H12N2O6, MW:246.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The synthesis of a global database for actual nitrogen loss rates represents a significant leap forward in our ability to understand and predict the fate of reactive nitrogen in coastal and marine systems. The data confirm that denitrification and anammox are major sinks for Nr, with their dynamics and relative contributions being shaped by a predictable set of environmental drivers including temperature, organic carbon, and nutrient availability. The emergence of manganammox as a demonstrable pathway further expands the known microbial repertoire for nitrogen removal.

This consolidated dataset and the associated methodological frameworks provide an invaluable resource for the research community. They enable robust cross-system comparisons, help identify global measurement gaps, and are crucial for the parameterization and validation of mechanistic biogeochemical models. These models are essential tools for forecasting ecosystem responses to ongoing global change and for informing effective environmental management strategies to combat nitrogen pollution.

Critical Roles of Rare Microbial Species in Community Stability and Function

Recent advances in microbial ecology have revolutionized our understanding of rare species contributions to ecosystem functioning. In anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) communities within coastal sediments, rare microbial taxa demonstrate disproportional significance in maintaining community stability, functional resilience, and metabolic versatility. This technical review synthesizes cutting-edge research on the mechanisms through which rare species stabilize anammox consortia, their specialized functional roles, and the complex interspecies interactions they mediate. We present comprehensive quantitative analyses of anammox bacterial distribution across estuarine environments, detailed methodological frameworks for investigating rare taxa, and essential reagent solutions for experimental research. The findings underscore that rare anammox species, though numerically insignificant, serve as critical reservoirs of genetic diversity and functional potential, enabling community adaptation to fluctuating environmental conditions in coastal sedimentary ecosystems.

The stability and function of microbial communities in coastal sediments have profound implications for global nitrogen cycling and ecosystem health. Within these communities, a persistent paradox exists: while abundant taxa dominate biomass, rare taxa consistently demonstrate outsized ecological importance [7]. In anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) bacterial consortia, which contribute significantly to nitrogen loss in marine environments, rare species constitute a hidden majority that maintains functional resilience amid environmental perturbations [7]. The critical roles of these rare microbial species extend beyond mere taxonomic diversity to encompass functional insurance, metabolic versatility, and network stability.

Anammox processes in coastal sediments remove fixed nitrogen through the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium with nitrite as an electron acceptor, producing dinitrogen gas without intermediate greenhouse gas emissions [2] [40]. This metabolically specialized process is mediated by bacterial lineages within the phylum Planctomycetota, including the genera Candidatus Scalindua, Candidatus Brocadia, Candidatus Kuenenia, Candidatus Jettenia, and Candidatus Anammoxoglobus [2] [41]. While these communities appear dominated by a few abundant taxa, recent high-resolution molecular analyses have revealed extensive rare biospheres that fundamentally influence community dynamics [7].