Engineering Microbial Consortia: Division of Labor Strategies for Advanced Biomanufacturing and Therapeutics

This article explores the paradigm of engineering microbial consortia for division of labor, a transformative approach in synthetic biology that distributes complex biological tasks across specialized microbial subpopulations.

Engineering Microbial Consortia: Division of Labor Strategies for Advanced Biomanufacturing and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm of engineering microbial consortia for division of labor, a transformative approach in synthetic biology that distributes complex biological tasks across specialized microbial subpopulations. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of synthetic ecology and communication networks that enable consortium design. The article details cutting-edge methodological tools—from quorum sensing circuits to CRISPR-based control—and their application in metabolic engineering and biomedicine. We address critical challenges in consortium stability and optimization, offering troubleshooting strategies for population dynamics and metabolic cross-talk. Finally, we present rigorous validation frameworks, including computational modeling and comparative performance analyses, to guide the implementation of robust, therapeutic-grade microbial communities. This comprehensive resource bridges fundamental science with translational applications, positioning engineered consortia as powerful platforms for next-generation bioproduction and therapeutic development.

The Principles and Promise of Microbial Division of Labor

Synthetic microbial consortia are engineered communities comprising multiple microbial strains designed to perform complex tasks through division of labor (DoL). In these systems, metabolic pathways or computational functions are distributed among specialized consortium members, mimicking the ecological interactions found in natural communities [1] [2]. This approach has evolved from observing natural ecosystems where microorganisms interact with each other and their environment to efficiently utilize available resources [3].

The implementation of DoL addresses a fundamental challenge in synthetic biology: metabolic burden. When a single microbial host is engineered to perform multiple complex tasks, it must allocate limited resources among competing functions, often leading to compromised performance in a phenomenon described as the "metabolic cliff" [2]. Distributing these tasks across a consortium reduces the individual burden on each strain, leading to improved productivity and stability [4]. DoL strategies enable the construction of robust microbial cell factories with expanded metabolic capabilities that exceed what can be achieved with single strains [3] [1].

Table 1: Advantages of Division of Labor in Synthetic Microbial Consortia

| Advantage | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Metabolic Burden | Distribution of genetic circuits and pathway enzymes across multiple strains [2] | Improved growth rates and higher product yields [4] |

| Expanded Functional Capabilities | Combination of specialized metabolic functions from different species [1] | Access to complex biosynthetic pathways not possible in single strains [3] |

| Improved Stability | Compensation for performance fluctuations through community robustness [1] | More predictable and consistent production outcomes [2] |

| Spatial Organization | Compartmentalization of incompatible metabolic processes [2] | Protection of toxic intermediates and optimized pathway efficiency [1] |

Quantitative Evidence: Establishing Structure-Function Relationships

Understanding the relationship between microbial community structure and function is crucial for designing effective consortia. A quantitative meta-analysis of decomposition studies demonstrated that microbial community composition has a strong and pervasive effect on litter decay rates, rivaling the influence of litter chemistry itself [5]. This foundational research establishes that specific microbial inocula can directly drive ecosystem process rates, providing a scientific basis for engineering consortia with predictable functions.

The strength of microbial community structure-function relationships varies depending on environmental conditions and the specific function being measured. For "broad" processes like CO~2~ respiration carried out by many taxa, relationships may be weaker due to functional redundancy, while "narrow" processes like denitrification show stronger linkages to specific community structures [5]. This distinction is critical when designing consortia for specific applications, as it determines the required level of engineering precision.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence for Microbial Community Structure-Function Relationships

| Study Approach | Key Finding | Implication for Consortium Design |

|---|---|---|

| Common Garden Experiments | Microbial inoculum from different environments resulted in varying carbon mineralization rates under controlled conditions [5] | Source environment of consortium members predicts functional output |

| Diversity-Function Experiments | Reduction of bacterial diversity by 99.9% did not always affect carbon mineralization, but strongly impacted denitrification [5] | Functional redundancy varies by process; critical functions require specific members |

| Reciprocal Transplants | Effects of microbial community composition on functioning sometimes dissipated over time [5] | Consortium stability requires ongoing management or engineered stabilization |

| Metabolic Modeling | Cross-feeding networks and emergent properties influence community function [5] | Computational approaches can predict consortium behavior before construction |

Engineering Principles and Interaction Typologies

Engineering functional consortia requires careful design of microbial interactions. Six fundamental ecological relationships can be programmed between consortium members: neutralism, commensalism, mutualism, amensalism, competition, and predation [4]. For stable consortium function, mutualistic interactions are particularly valuable, where both populations benefit from the interaction [2].

Natural ecosystems provide inspiration for engineering principles. In lichen, a classic symbiotic system, algae and fungi spontaneously self-assemble, with fungi providing shelter and metabolites while algae contribute carbon sources [1]. This self-organization capability, if incorporated into engineered living materials (ELMs), could eliminate complex embedding procedures during fabrication [1]. Similarly, in the human gut, anaerobic bacterial species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Desulfovibrio piger cross-feed through metabolite exchanges (lactate and acetate), maintaining community stability and promoting health [1].

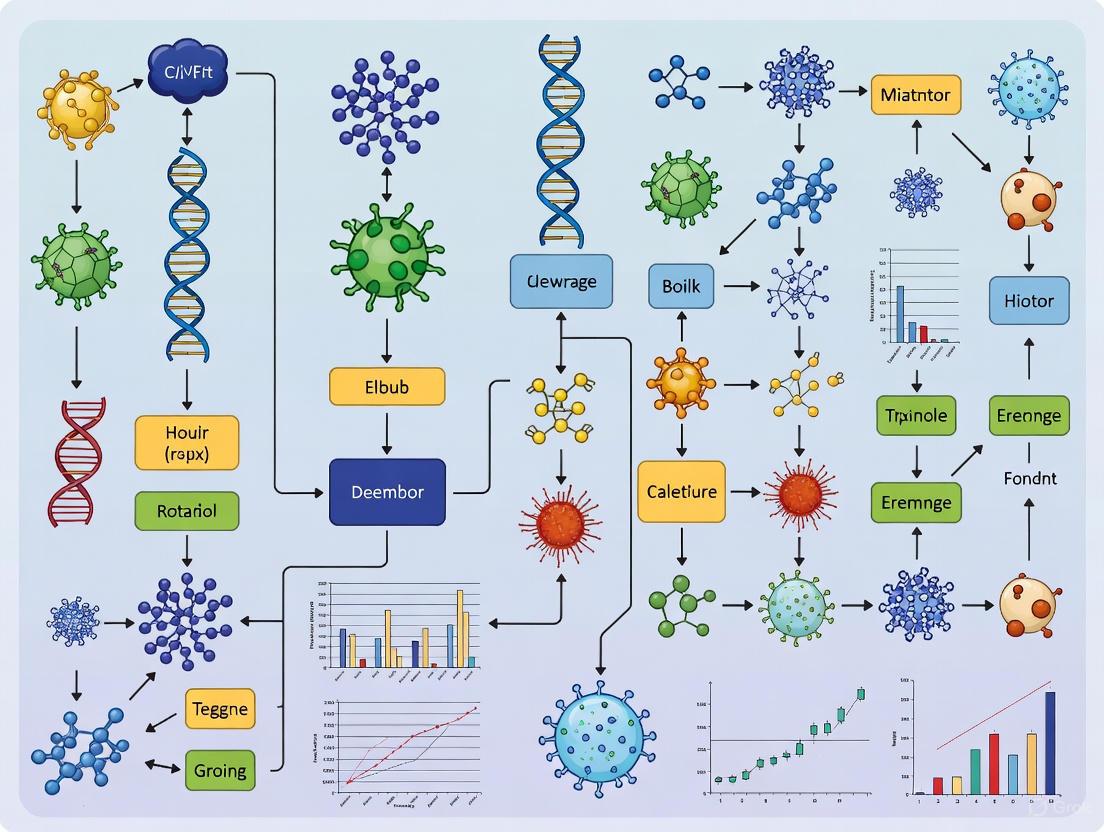

Diagram 1: Microbial interaction types and engineering strategies. Mutualistic interactions enhance consortium stability through strategies like metabolic cross-feeding.

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Engineering

Protocol 4.1: Designing Division of Labor for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

Purpose: Distribute a multi-step metabolic pathway across two microbial strains to reduce individual metabolic burden and improve product yield.

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strain A: Contains genes for initial pathway steps

- Engineered S. cerevisiae strain B: Contains genes for final pathway steps

- Appropriate selective media

- Inducers for pathway activation

- Metabolite standards for HPLC analysis

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Independently cultivate and verify the functionality of each engineered strain in monoculture.

- Inoculum Optimization: Test different inoculation ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:5, 1:10) to identify the ratio that maximizes product formation.

- Co-culture Setup: Inoculate strains together in fresh medium containing required nutrients and inducers.

- Metabolite Monitoring: Sample culture supernatant at regular intervals (e.g., every 3-6 hours) for HPLC analysis of intermediate and final products.

- Population Dynamics Tracking: Use selective plating or flow cytometry with strain-specific markers to monitor population ratios over time.

- Product Harvest: When product concentration peaks, separate cells from supernatant for product purification.

Troubleshooting:

- If one strain dominates: Implement nutritional divergence or population control circuits.

- If intermediate accumulation occurs: Optimize transporter expression or adjust strain ratios.

- If productivity declines: Consider cell immobilization to maintain population stability [2].

Protocol 4.2: Implementing Population Control Using Synchronized Lysis Circuits

Purpose: Maintain stable population ratios in a co-culture using programmed population control.

Materials:

- Two E. coli strains with orthogonal synchronized lysis circuits (SLCs)

- Appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance

- Acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) inducers for quorum sensing activation

- Lysis monitoring dyes (e.g., propidium iodide)

Procedure:

- Circuit Characterization: Independently characterize each SLC strain to determine lysis thresholds and dynamics.

- Initial Co-culture: Combine strains at desired starting ratio in fresh medium.

- Population Monitoring: Track population densities using OD~600~ and strain-specific fluorescence markers.

- Lysis Verification: Confirm programmed lysis events through viability staining and culture microscopy.

- Long-term Stability Assessment: Maintain cultures in continuous or batch mode for multiple generations to verify stability.

- Functional Output Measurement: Assess target function (e.g., metabolite production) throughout the experiment.

Applications: This approach enables stable coexistence of strains with different growth rates, preventing culture collapse due to competitive exclusion [4].

Diagram 2: Metabolic pathway division between two specialized strains. Strain A performs initial pathway steps, exporting intermediates that Strain B converts to final product.

Essential Research Reagents and Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Consortium Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Consortium Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [6], Conjugative plasmids [6], Transposon systems [6] | Introduction of pathway genes and control circuits into microbial chassis |

| Communication Modules | AHL-based quorum sensing [4], Bacteriocin communication systems [4] | Enable coordinated behavior and population control between strains |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, Auxotrophic markers | Maintenance of engineered populations and selective pressure for stability |

| Metabolic Reporters | Fluorescent proteins, Enzymatic reporters (β-galactosidase, luciferase) | Monitoring population dynamics and functional output in real-time |

| Strain Chassis | Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis, Lactococcus lactis [2] [6] | Host organisms with well-characterized genetics and metabolic capabilities |

| Methyl 6-acetoxyangolensate | Methyl 6-acetoxyangolensate, MF:C29H36O9, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-aminooxy-PEG12-NHS ester | Fmoc-aminooxy-PEG12-NHS ester, MF:C46H68N2O19, MW:953.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Bioproduction and Therapeutics

Consolidated Bioprocesses for Biofuel Production

Microbial consortia enable consolidated bioprocesses (CBP) that convert complex substrates directly into valuable products. For example, co-cultures of Clostridium thermocellum (cellulose degrader) with Thermoanaerobacter strains (ethanol producer) improved ethanol production by 4.4-fold compared to monoculture [2]. Similarly, fungal-bacterial consortia pairing Trichoderma reesei (cellulase producer) with engineered E. coli (isobutanol producer) achieved titers up to 1.9 g/L from cellulosic biomass [2].

Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Applications

Division of labor approaches have enabled production of complex pharmaceuticals that are challenging to synthesize using single strains. A prominent example is the mutualistic co-culture of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for production of oxygenated taxanes, where stability of the co-culture composition increased product titer and decreased variability [4]. In therapeutic applications, engineered consortia are being developed for gut microbiome modulation, with species like Lactococcus lactis modified to express human metabolic enzymes such as ADH1B, reducing blood acetaldehyde and liver damage in animal models [6].

Analytical Methods for Consortium Validation

Advanced multi-omics approaches are essential for characterizing synthetic consortia and verifying functional outcomes. Strain-level resolution in taxonomic profiling is critical, as functional differences often exist at the sub-species level [7]. Metagenomic approaches using single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or variable region identification can differentiate strains, while metatranscriptomics reveals which genes are actively expressed under specific conditions [7].

Metabolic flux analysis using ^13^C-labeled substrates provides quantitative insights into cross-feeding dynamics and pathway efficiency within consortia [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for optimizing consortium design by identifying bottlenecks in metabolite exchange and utilization. When combined with computational modeling, these analytical methods enable predictive design of consortia with desired functional properties.

In microbial metabolic engineering, the challenge of implementing complex tasks in single populations presents significant limitations. As pathway complexity increases, the metabolic burden on a single host strain often leads to a drastic drop in cell performance and productivity [4] [2]. This burden occurs because microbial hosts must allocate limited resources among different tasks, creating a fundamental counterforce against any engineered pathway [2]. The synergistic combination of metabolic burden and cell stress leads to what has been termed the "metabolic cliff," where even small growth perturbations can cause undesired metabolic responses and catastrophic loss of production yields [2].

Engineered microbial consortia represent a promising strategy to address these challenges by distributing complex tasks among multiple populations [4]. This approach reduces individual metabolic burden by assigning different pathway steps to specialized strains, potentially expanding the functional space for complex biochemical production [8]. Division of labor (DoL) enables the partitioning of metabolic pathways across proper hosts, though this introduces new challenges including complex subpopulation dynamics, proliferation of cheaters, intermediate metabolite dilution, and transport barriers between species [2].

Key Concepts and Ecological Interactions

Fundamental Interaction Types in Microbial Consortia

Engineering functional microbial consortia requires programming specific ecological interactions between microbial populations. These interactions can be categorized into several fundamental types that determine community dynamics and stability [4]:

- Mutualism: Both populations benefit from the interaction, creating stable interdependencies

- Commensalism: One population benefits while the other remains unaffected

- Predation: One population consumes another, often creating oscillatory dynamics

- Competition: Both populations negatively affect each other, potentially leading to exclusion

- Amensalism: One population is inhibited while the other remains unaffected

- Neutralism: No significant interaction occurs between populations

Programming Stable Consortia Through Engineered Interactions

Table 1: Strategies for Engineering Stable Microbial Consortia

| Strategy | Mechanism | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Feedback Control | Uses synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) with QS molecules to induce lysis at high density [4] | Prevents overgrowth of faster-growing strains in co-culture |

| Nutritional Divergence | Engineering strains to consume different substrates or cross-feed metabolites [2] | Reduces direct competition for resources |

| Spatial Segregation | Cell immobilization or compartmentalization to create physical niches [4] [2] | Enables coexistence through physical separation |

| Mutualistic Cross-feeding | Designing interdependent metabolite exchange networks [4] [2] | Creates stable, mutually dependent communities |

| Dynamic Division of Labor (DDOL) | Using horizontal gene transfer (HGT) for reversible pathway distribution [9] | Maintains burdensome pathways with improved stability |

Application Notes: Experimental Implementation

Protocol 1: Establishing a Mutualistic Co-culture for Metabolic Production

Background: This protocol outlines the establishment of a mutualistic consortium between E. coli and S. cerevisiae for improved production of oxygenated taxanes, demonstrating how division of labor can enhance stability and productivity compared to competitive co-cultures [4] [2].

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strain (e.g., acetate producer)

- Engineered S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., acetate consumer and taxane producer)

- Appropriate selective media (e.g., M9 minimal media, YPD)

- Inducer compounds as required for pathway activation

- Bioreactor or shake flask culture equipment

- HPLC system for metabolite quantification

Procedure:

- Pre-culture Preparation:

- Inoculate monocultures of each strain in separate vessels

- Grow overnight to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8)

Inoculation Optimization:

- Test inoculation ratios from 1:10 to 10:1 (E. coli:yeast)

- Monitor population dynamics over 24-48 hours

- Select ratio that maintains stable co-culture composition

Co-culture Cultivation:

- Combine strains at optimized ratio in fresh media

- Maintain appropriate temperature, aeration, and pH conditions

- Sample periodically for population counting and metabolite analysis

Monitoring and Analysis:

- Use selective plating to quantify individual population densities

- Measure acetate concentration to verify cross-feeding

- Quantify taxane production compared to monoculture controls

Troubleshooting:

- If one population dominates, adjust inoculation ratio or implement population control circuits

- If metabolite exchange is inefficient, engineer improved transport systems

- For pathway imbalance, optimize gene expression levels via promoter engineering

Protocol 2: Implementing Programmed Population Control

Background: This protocol describes the implementation of synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) to generate stable co-cultures of engineered E. coli populations through programmed negative feedback, preventing competitive exclusion [4].

Materials:

- E. coli strains equipped with orthogonal SLC circuits

- Quorum sensing molecules (AHL variants)

- Lysis gene constructs (e.g., E protein from phage ΦX174)

- Antibiotics for selective pressure

- Flow cytometry equipment for population analysis

Procedure:

- Circuit Validation:

- Verify functionality of individual SLC circuits in monoculture

- Confirm QS-mediated lysis activation at appropriate cell densities

- Optimize induction thresholds for each population

Co-culture Establishment:

- Inoculate strains expressing orthogonal SLC circuits

- Monitor population dynamics every 2-4 hours

- Confirm oscillatory behavior without extinction events

Pathway Integration:

- Introduce metabolic pathway segments into SLC-equipped strains

- Verify maintenance of pathway function alongside population control

- Measure product yield compared to uncontrolled consortia

Quantitative Analysis of Consortium Performance

Comparative Performance Across Cultivation Strategies

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Microbial Cultivation Strategies

| Cultivation Strategy | Typical Production Increase | Stability Duration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoculture | Baseline | High (weeks-months) | Simple pathways, low-burden production [2] |

| Static Division of Labor (SDOL) | 2-5× improvement for high-burden pathways | Medium (days-weeks) with controls | Complex natural products, bioconversions [9] |

| Dynamic Division of Labor (DDOL) | Superior for very high burden pathways (λT > 2.5) | High (weeks) via HGT | Extremely burdensome pathways, community-based systems [9] |

| Mutualistic Consortia | 3-4× titer improvement reported [4] | High (weeks) | Substrate utilization, detoxification [4] [2] |

The performance advantages of consortia strategies become particularly pronounced as pathway complexity and burden increase. Modeling studies demonstrate that while monoculture outperforms for low-burden pathways (λT < 1.5), DDOL provides superior performance for high-burden pathways (λT > 2.5) where monoculture fails completely [9]. The effective biomass of DDOL systems can be maintained at 60-80% of carrying capacity even for highly burdensome pathways that would collapse monoculture systems [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Microbial Consortia Engineering

| Reagent/Circuit | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing Systems (Lux, Las, Rhl, etc.) | Enable intercellular communication and density-dependent regulation [4] [8] | Population control, synchronization, coordinated behaviors |

| Bacteriocin Systems | Mediate competitive interactions through targeted killing [4] [8] | Population ratio control, ecosystem structuring |

| Synchronized Lysis Circuits | Implement negative feedback through programmed cell lysis [4] | Population control, metabolite release |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer Systems | Enable dynamic pathway distribution [9] | Dynamic division of labor, functional stabilization |

| Orthogonal AHL Signals | Reduce crosstalk in complex consortia [8] | Multi-strain communication networks |

| Metabolic Biosensors | Monitor metabolite levels and regulate pathway expression [2] | Pathway optimization, dynamic regulation |

| m-PEG10-t-butyl ester | m-PEG10-t-butyl ester, MF:C26H52O12, MW:556.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethylene glycol diacrylate | Ethylene glycol diacrylate, CAS:2274-11-5, MF:C8H10O4, MW:170.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Computational Modeling and Design

Mathematical modeling provides critical guidance for consortia design, particularly for predicting population dynamics and optimizing system parameters. The population dynamics of HGT-mediated DDOL systems typically exhibit biphasic behavior: an initial propagation phase dominated by growth of less-burdened strains, followed by a balancing phase where gene transfer dominates and strains reach steady-state levels [9].

Essential modeling parameters include:

- Transfer rates (η): Typically 0.05-0.15 for effective DDOL [9]

- Burden coefficients (λ): Representing metabolic cost of pathway segments

- Hill coefficient (m): Modeling nonlinear burden effects (typically m > 1) [9]

Visualizing Consortia Interactions and Workflows

Microbial Consortia Design Workflow

Metabolic Burden Comparison Across Strategies

Engineered Interaction Networks in Microbial Consortia

The rational design of microbial consortia represents a frontier in synthetic biology, offering a powerful strategy to overcome the limitations of single-strain engineering. Division of labor (DoL)—the distribution of complex tasks across specialized microbial subpopulations—can alleviate metabolic burden, improve functional stability, and expand overall system capabilities [10] [11]. This paradigm shift enables the engineering of sophisticated community-level behaviors for applications ranging from biomanufacturing to living materials and therapeutics.

Underpinning the functional robustness of these consortia are precisely engineered ecological interactions. By harnessing the principles of mutualism, competition, and predation, researchers can program stable, self-regulating communities with predictable dynamics. This Application Note provides a detailed framework for designing, constructing, and analyzing engineered microbial consortia based on these foundational ecological blueprints, contextualized within a broader thesis on the genetic manipulation of microbial systems for DoL research.

Engineering Blueprints and Design Principles

The table below summarizes the core ecological interactions used as design blueprints for synthetic microbial consortia, their engineering mechanisms, and their impact on community stability and function.

Table 1: Engineering Blueprints for Ecological Interactions in Microbial Consortia

| Interaction Type | Engineering Mechanism | Key Components & Signals | Effect on Community Dynamics | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Cross-feeding of essential metabolites or detoxification of the shared environment [4] [10]. | Amino acids, sugars, organic acids (e.g., acetate [4]), vitamins. | Enhances coexistence and stability; increases biomass and productivity [4] [11]. | Taxane precursor production [4], co-culture bioprocessing [10] [12]. |

| Competition | Engineering strains to compete for the same limited nutrient source [4]. | Limited carbon, nitrogen, or phosphate sources. | Can lead to exclusion unless mitigated; requires control strategies for stability [4] [8]. | Model systems for studying population dynamics and evolutionary pressure. |

| Predation | Use of toxin-antitoxin or lytic systems where one strain kills another [4] [8]. | Bacteriocins [4], CcdB/CcdA toxin-antitoxin [4], contact-dependent inhibition systems [8]. | Creates oscillatory population dynamics; can be used for population control or pattern formation [4]. | Synthetic predator-prey ecosystems for biocomputing and dynamic control [4]. |

| Programmed Neg. Feedback | Quorum Sensing (QS)-controlled lysis or toxin expression to prevent overgrowth [4] [8]. | AHL-based QS molecules, synchronized lysis circuits (SLC), protein E lysis [4] [8]. | Stabilizes co-cultures by preventing competitive exclusion; enables steady-state coexistence [4]. | Stable co-culture of strains with different growth rates [4]. |

Quantitative Dynamics and Stability Analysis

Successful consortium design requires a quantitative understanding of population dynamics. The table below summarizes critical parameters and control strategies for maintaining stable, functional interactions.

Table 2: Quantitative Dynamics and Stability Control in Engineered Consortia

| Interaction Type | Characteristic Dynamics | Key Stability Parameters | Control & Mitigation Strategies | Modeling Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Stable coexistence; increased total biomass and product titer [4] [10]. | Metabolite exchange rate, relative growth yields. | Optimize inoculation ratios [10]; engineer tight metabolic coupling [11]. | Metabolic models predict cross-feeding fluxes and optimal strain ratios [11]. |

| Competition | Exclusion of the slower-growing strain unless stabilized [4]. | Relative growth rates, nutrient concentration. | Programmed negative feedback [4]; nutritional divergence [10]; spatial segregation [4] [12]. | Models show that negative feedback can offset growth rate differences [4]. |

| Predation | Oscillations in predator and prey densities [4]. | Predation rate, prey growth rate, signal diffusion. | Vary inducer concentration to tune between extinction, oscillation, or stable states [4]. | Mathematical models can predict conditions for sustained oscillations versus population collapse [4]. |

| General Stability | Dependent on interaction type and strength. | Inoculation ratio, nutrient flow (e.g., in chemostats) [10]. | Biosensors for real-time monitoring [10]; cell immobilization [10] [12]; evolution of mutualistic dependence [10]. | Higher-order interactions in multi-strain communities can be predicted from pairwise models [4] [8]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a Mutualistic Consortium for Metabolic Pathway Division

This protocol details the creation of a two-strain mutualistic system for the enhanced production of taxanes, based on the work of Zhou et al. [4].

1. Design and Cloning

- Strain A (E. coli): Engineer an E. coli strain to overexpress the upstream modules of the taxane biosynthetic pathway. This strain will produce and excrete acetate as an intermediate.

- Strain B (S. cerevisiae): Engineer a S. cerevisiae strain to express the downstream modules of the pathway. This strain must be able to use acetate as its sole carbon source.

- Genetic Tools: Use standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., Golden Gate assembly, Gibson assembly) for plasmid construction. Prefer genomic integration for long-term genetic stability over serial cultivation.

2. Cultivation and Stability Analysis

- Inoculation: Co-culture Strain A and Strain B in a minimal medium with a primary carbon source that only Strain A can efficiently utilize (e.g., glucose). Test different inoculation ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:10, 10:1 cell counts) to identify the optimum for stability and production.

- Monitoring: Sample the culture periodically over 24-72 hours.

- Cell Density: Use flow cytometry or plating on selective media to track the population dynamics of each strain.

- Metabolite Analysis: Measure acetate concentration in the supernatant using HPLC or enzymatic assays to ensure consumption by Strain B.

- Product Titer: Quantify the final taxane product using LC-MS.

- Validation: Compare the product titer, stability, and variability against competitive co-cultures and monoculture controls.

Protocol: Implementing a Predator-Prey System for Oscillatory Dynamics

This protocol outlines the construction of a synthetic predator-prey ecosystem using QS communication, as pioneered by Balagaddé et al. [4].

1. Circuit Design and Strain Engineering

- Prey Strain (E. coli): Engineer the prey to produce a QS signal (e.g., AHL from LuxI) constitutively. This strain should also carry a "suicide" gene (e.g., ccdB) under the control of a QS-responsive promoter (e.g., plux). The promoter is activated by a different AHL signal produced by the predator.

- Predator Strain (E. coli): Engineer the predator to constitutively express the ccdB suicide gene. Introduce a circuit for the expression of an antidote (e.g., ccdA) under the control of a promoter activated by the AHL signal produced by the prey.

2. Cultivation and Dynamic Monitoring

- Setup: Co-culture the two strains in a microchemostat or a well-controlled bioreactor to maintain constant environmental conditions.

- Induction: Apply varying concentrations of chemical inducers (e.g., IPTG or aTc) to tune the expression levels of key circuit components.

- Data Collection: Sample the culture frequently (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) over 48-96 hours. Use flow cytometry with strain-specific fluorescent markers (e.g., GFP vs. RFP) to track real-time population dynamics of both predator and prey.

- Phenotype Characterization: Depending on the inducer concentration, validate the three predicted dynamic regimes:

- Prey Domination: Low predator induction.

- Oscillatory Behavior: Intermediate induction levels.

- Predator Domination: High predator induction.

Visualization of Core Signaling and Control Pathways

Quorum Sensing and Lysis Circuit for Population Control

The following DOT code generates a diagram illustrating the genetic logic of a synchronized lysis circuit used for programmed negative feedback.

Metabolic Cross-Feeding in a Mutualistic System

The following DOT code visualizes the metabolite exchange that forms the basis of a mutualistic interaction for divided metabolic pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Engineering Ecological Interactions

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Consortium Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling Molecules | Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) [4] [8]; α-factor pheromone (yeast) [8]. | Enable quorum sensing and inter-strain communication for coordinated behaviors and feedback control. |

| Toxin/Antitoxin Systems | CcdB/CcdA [4]; Bacteriocins [4] [8]; Contact-dependent Inhibition (CDI) systems [8]. | Implement predation, competition, and population control by selectively eliminating target strains. |

| Metabolic Genes | Amino acid biosynthetic genes; Sugar transporters; Acetate utilization pathways [4]. | Engineer cross-feeding and mutualism by enabling exchange of essential metabolites between strains. |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes; Auxotrophic complementation markers (e.g., leuB, trpC). | Maintain plasmid stability and enforce the coexistence of interdependent strains in a consortium. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, RFP, and other spectral variants. | Track population dynamics and gene expression in real-time within a mixed culture using flow cytometry or microscopy. |

| Modeling Software | COBRA tools [11]; Custom ODE models in MATLAB or Python. | Predict community metabolic fluxes, population dynamics, and design optimal intervention strategies. |

| 4,5,6-Trichloroguaiacol | 4,5,6-Trichloroguaiacol|High-Purity Reference Standard | 4,5,6-Trichloroguaiacol is a chlorinated guaiacol for environmental and degradation process research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| trans-2-Pentenoic acid | trans-2-Pentenoic acid, CAS:626-98-2, MF:C5H8O2, MW:100.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks

The strategic engineering of mutualism, competition, and predation provides a robust toolkit for constructing stable, high-performance microbial consortia. By translating ecological principles into genetic circuits, researchers can achieve sophisticated division of labor, paving the way for advanced applications in sustainable biomanufacturing, next-generation living materials, and precision microbiome therapeutics. The protocols and frameworks provided here offer a foundational roadmap for harnessing these powerful ecological blueprints.

Application Note: Leveraging Natural and Engineered Microbial Communication

The genetic manipulation of microbial consortia for a division of labor requires a deep understanding of both natural bacterial communication and engineered genetic control. Natural quorum sensing (QS) systems allow bacteria to coordinate population-wide behaviors, such as virulence factor production and biofilm formation, based on cell density [13]. In parallel, the field of synthetic biology provides the tools to engineer robust genetic circuits that can be installed in microbial chassis to impose novel, programmed functions. When combined, these paradigms enable the design of consortia where specialized tasks are distributed among sub-populations, enhancing the overall stability and efficiency of the system. This application note details core tools and protocols for advancing research in this domain, focusing on practical implementation.

Application Note 1: Exploiting Native Quorum Sensing Pathways

Background & Principle: The opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa possesses one of the most finely tuned and convoluted QS networks, making it a rich source of characterized and interoperable communication parts [13]. Its system is hierarchically structured, primarily involving the Las, Rhl, and Pqs systems, with a fourth, the Iqs system, interconnecting them with the phosphate stress response [13]. Each system relies on a specific autoinducer and its cognate transcriptional activator. The hierarchical nature allows for the engineering of complex logic gates based on natural biological components.

Key Protocols:

- Signal Detection and Quantification: For the Las and Rhl systems, which use N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL) and N-butyryl-L-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) respectively, protocols involve liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for absolute quantification [14]. For the Pqs system, the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) can be extracted from acidified ethyl acetate and similarly analyzed [13].

- Genetic Manipulation of Pathways: To harness these pathways, key regulatory genes (e.g., lasI/R, rhlI/R, pqsA-E, ambBCDE) can be knocked out or modulated using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) systems [15] [13]. This allows for the dissection of pathway contributions and the creation of engineered sender and receiver strains.

Table: Key Quorum Sensing Systems in P. aeruginosa

| QS System | Autoinducer (AI) | Receptor | Key Regulatory Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Las | N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL) | LasR | Top-level controller; positively regulates Rhl and Pqs systems [13] |

| Rhl | N-butyryl-L-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) | RhlR | Controls virulence factors; negatively controls Pqs system [13] |

| Pqs | 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (PQS) | PqsR | Activates RhlI expression; controls a large regulon of virulence genes [13] |

| Iqs | 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-thiazole-4-carbaldehyde (IQS) | Unknown | Connects Las system and phosphate stress response to downstream QS [13] |

Figure 1: Hierarchical Quorum Sensing Network in P. aeruginosa. The diagram shows the interplay between the four main QS systems, with the Las system at the top. Solid arrows indicate positive regulation, while the dashed arrow indicates negative regulation [13].

Application Note 2: Engineering Evolutionarily Robust Genetic Circuits

Background & Principle: A fundamental roadblock in synthetic biology is the evolutionary instability of engineered gene circuits. Circuit expression imposes a metabolic burden on the host, diverting resources like ribosomes and amino acids away from growth [16]. This creates a selective pressure where faster-growing, non-producing mutants overtake the population [16]. For a division of labor in consortia, where stable function over many generations is crucial, mitigating this burden is essential.

Solution & Protocol: Implementing genetic feedback controllers is a promising strategy to extend functional longevity. Recent research using multi-scale "host-aware" computational models suggests that specific controller architectures can significantly improve circuit half-life [16].

Key Controller Designs:

- Intra-Circuit Negative Feedback: The circuit's output protein represses its own expression. This reduces resource burden and prolongs short-term performance but may not prevent long-term evolutionary failure [16].

- Growth-Based Feedback: The controller actuates based on the host's growth rate. This directly links circuit function to a key fitness indicator and has been shown to extend the functional half-life of circuits most effectively in the long term [16].

- Post-Transcriptional Control: Using small RNAs (sRNAs) to silence circuit mRNA outperforms transcriptional control via transcription factors. The sRNA mechanism provides an amplification step, enabling strong control with reduced controller burden [16].

Table: Performance Metrics of Different Genetic Controllers for Evolutionary Longevity

| Controller Architecture | Input Sensed | Actuation Method | Short-Term Performance (τ±10) | Long-Term Half-Life (τ50) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (No Control) | N/A | N/A | Low | Low | Baseline for comparison |

| Intra-Circuit Feedback | Output per cell | Transcriptional (TF) | High | Medium | Prolongs short-term stability [16] |

| Intra-Circuit Feedback | Output per cell | Post-transcriptional (sRNA) | High | Medium-High | Strong control with lower burden [16] |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Host growth rate | Transcriptional (TF) | Medium | High | Best for long-term persistence [16] |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Host growth rate | Post-transcriptional (sRNA) | Medium | Very High | Optimal for long-term function [16] |

Protocol for In Silico Modeling:

- Model Setup: Develop an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model capturing host-circuit interactions, including resource competition (ribosomes, metabolites) and growth dynamics [16].

- Define Mutation States: Implement a mutation scheme where the engineered circuit can transition to states with reduced function (e.g., 100%, 67%, 33%, 0% of nominal expression) [16].

- Simulate Population Dynamics: Run the model in simulated batch culture conditions, allowing mutants to arise and compete based on their growth rates.

- Quantify Longevity: Measure the time taken for the total population output to fall below 50% of its initial value (τ50) and the time it remains within ±10% of the initial output (τ±10) [16].

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Engineering

Protocol: Implementing a Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology Toolkit inAcinetobacter baumannii

Objective: To enable the rational design of genetic circuits in the high-priority pathogen A. baumannii for consortium research, leveraging a modular synthetic biology toolkit [15].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Acinetobacter baumannii target strain.

- Plasmid Vectors: Toolkit vectors (e.g., pABBr and pABBm) with characterized replication origins [15].

- Promoter Library: A set of constitutive and inducible promoters (e.g., PBAD, Ptet) cloned into BioBrick vectors [15].

- CRISPRi System: A modular CRISPR interference system for targeted gene repression [15].

Procedure:

- Part Characterization: Clone the promoter library upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) into the chosen plasmid vector. Transform into A. baumannii.

- Flow Cytometry: Measure fluorescence intensity over time to characterize promoter strength and dynamics under inducing/non-inducing conditions.

- CRISPRi Knockdown: Design single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting specific genes of interest. Clone sgRNAs into the CRISPRi plasmid and co-transform with the dCas9 expression vector.

- Validation: Quantify knockdown efficiency via qRT-PCR or Western Blot to confirm functional repression of target genes.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Implementing a Synthetic Biology Toolkit. The process begins with characterizing genetic parts, moves to circuit assembly and regulatory implementation, and concludes with functional validation [15].

Protocol: AI-Guided Analysis of Microbial Community Metabolomics

Objective: To decode the hidden communication within a synthetic microbial consortium by identifying significant relationships between specific bacterial members and their metabolite outputs using advanced AI [17].

Materials:

- Samples: Longitudinal metagenomic and metabolomic data from the microbial consortium.

- Software: The VBayesMM workflow (or similar Bayesian neural network tool) [17].

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing cluster, as analysis is computationally demanding.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Process 16S rRNA amplicon or whole-genome sequencing data to get bacterial abundance tables. Preprocess mass spectrometry data for metabolite quantification.

- Model Input: Format the data into matrices where samples are rows, and features are columns (bacterial species/ASVs and metabolites).

- Run VBayesMM: Execute the Bayesian neural network model. VBayesMM will prioritize important bacteria-metabolite relationships while quantifying the uncertainty of its predictions [17].

- Interpret Results: Analyze the output to identify which bacterial groups are predicted to significantly influence the production of key metabolites. Use the uncertainty measures to focus on the most confident predictions for downstream experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Communication and Circuit Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BioBrick Parts (e.g., Promoters, RBS) | Standardized, modular DNA parts for genetic circuit assembly [15] | Building predictable genetic constructs in non-model bacteria like A. baumannii [15] |

| Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Vectors | Plasmid vectors capable of replication in a wide range of bacterial species [18] | Deploying the same genetic circuit across different chassis in a consortium to test host effects [18] |

| CRISPRi Repression System | A system using a dead Cas9 (dCas9) and sgRNA for targeted gene knockdown [15] | Fine-tuning native QS pathways or essential genes without knockout; implementing dynamic control [15] |

| Autoinducer Analogs | Synthetic molecules that mimic or inhibit natural QS signals [19] | Probing QS pathway function; externally manipulating communication in a consortium [13] [19] |

| Bayesian Neural Network (e.g., VBayesMM) | AI model that identifies significant relationships in complex omics data and reports prediction uncertainty [17] | Deciphering key bacteria-metabolite interactions in a synthetic gut microbiome consortium [17] |

| Graph Neural Network Model | Machine learning model for predicting future dynamics in microbial communities from time-series data [20] | Forecasting population shifts in a wastewater treatment consortium to pre-emptively adjust operational parameters [20] |

| Scopolamine methyl nitrate | Scopolamine methyl nitrate, CAS:6106-46-3, MF:C18H24N2O7, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isodecyl diphenyl phosphate | Isodecyl diphenyl phosphate, CAS:29761-21-5, MF:C22H31O4P, MW:390.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of genetic manipulation for division of labor (DoL) research, engineering microbial consortia represents a paradigm shift from monoculture-based microbial cell factories. By distributing biosynthetic tasks across specialized microbial strains, consortia mimic natural ecosystems to overcome fundamental limitations in metabolic engineering [2] [21]. This approach directly addresses the "metabolic cliff" phenomenon, where excessive pathway expression in single strains leads to catastrophic drops in performance due to metabolic burden and cellular stress [2]. The division of labor strategy effectively partitions metabolic load among consortium members, enabling complex operations that would be untenable for single organisms [2] [11].

This application note details the three fundamental advantages—robustness, modularity, and complex substrate utilization—that make engineered microbial consortia superior platforms for bioproduction and bioremediation. We provide experimental protocols and analytical frameworks specifically contextualized for research involving the genetic manipulation of microbial communities for DoL, enabling researchers to reliably construct, analyze, and optimize these sophisticated systems.

Robustness in Engineered Consortia

Conceptual Framework

Robustness in microbial consortia is defined as the persistence of a desired community-level function despite perturbations. For DoL systems, this function typically involves maintaining target production levels or degradation rates amidst fluctuations in environmental conditions or population dynamics [22]. This robustness emerges from several key mechanisms:

- Functional Redundancy: Multiple consortium members independently perform the same critical function, ensuring functional persistence even if one member is compromised [22].

- Distributed Function: A single function is achieved through complementary contributions from different members, creating a buffer against functional loss [22].

- Metabolic Cross-Feeding: Exchange of metabolites between members creates interdependent relationships that stabilize community composition and function [2] [22].

The stability of these interactions is crucial for industrial applications where consistent performance over extended cultivation periods is required [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Robustness

Table 1: Metrics for Assessing Consortia Robustness

| Metric Category | Specific Measurement | Experimental Method | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Stability | Coefficient of variation (CV) of strain ratios over time | Flow cytometry, selective plating | CV < 15% indicates high temporal stability |

| Functional Resilience | Recovery rate of product titer after perturbation (e.g., dilution, nutrient shift) | HPLC, GC-MS | Faster return to baseline indicates greater resilience |

| Structural Robustness | Maintenance of inoculation ratios under production conditions | qPCR with strain-specific primers | Stable ratios suggest compatible growth rates and interactions |

| Productivity Maintenance | Percentage of peak production maintained at stationary phase | Time-course metabolite profiling | < 20% drop indicates robust long-term function |

Protocol: Experimental Stress Testing for Robustness Assessment

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the robustness of a synthetic consortium designed for DoL against defined environmental perturbations.

Materials:

- Established synthetic co-culture with documented DoL

- Stressors: Antibiotic pulses (e.g., ampicillin, kanamycin), temperature shifts (±5°C from optimum), pH fluctuations (±0.5 units)

- Analytical equipment: Flow cytometer, HPLC system, plate reader

Procedure:

- Baseline Characterization: Grow the consortium under optimal conditions for 24 hours with periodic sampling (every 4 hours) to establish baseline population dynamics and product formation kinetics.

- Perturbation Application: At mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5), apply a single pulse perturbation:

- Antibiotic: Add sub-inhibitory concentration (determined via prior MIC testing)

- Temperature: Rapid shift to stress temperature

- pH: Adjust with sterile acid/base stock solutions

- Monitoring Phase: Continue sampling every 2 hours for 12 hours post-perturbation, then every 6 hours until stationary phase.

- Data Analysis: Calculate resilience metrics (e.g., time to return to 90% of pre-perturbation productivity) and compare population structure before and after perturbation using strain-specific markers.

Expected Outcomes: A robust consortium will maintain productivity within 70% of baseline and re-establish pre-perturbation population ratios within 24 hours. Successful DoL systems often show functional maintenance despite temporary population fluctuations [22].

Modularity in System Design and Engineering

Principles of Modular Consortia Design

Modularity in synthetic consortia refers to the organization of metabolic pathways into discrete, interchangeable units distributed among different strains. This architectural principle enhances both engineering flexibility and system robustness [11] [23]. In DoL systems, modular design allows for:

- Independent Optimization: Individual pathway modules can be optimized without complete system re-engineering

- Functional Encapsulation: Toxic intermediates can be confined to specific modules [2]

- Plug-and-Play Compatibility: Standardized genetic parts enable module exchange between different consortia [21]

Spatial organization strategies further enhance modularity by positioning strains to optimize metabolic flux and reduce cross-talk [23].

Protocol: Modular Consortia Construction via Pathway Segmentation

Purpose: To partition a multi-step biosynthetic pathway into functional modules for distribution between two microbial strains.

Materials:

- Chassis strains with compatible growth requirements (e.g., E. coli MG1655, B. subtilis 168)

- Plasmid vectors with orthogonal origin of replication and selection markers

- Modular genetic parts: Promoters, RBSs, terminators with minimal cross-talk

- Conjugation apparatus or electroporation equipment

Procedure:

- Pathway Deconstruction: Analyze the target biosynthetic pathway to identify:

- Natural substrate channeling points

- Toxic intermediate formation steps

- Cofactor requirements for each segment

- Module Assembly: Clone upstream pathway steps (e.g., substrate uptake and initial conversion) into one chassis strain, and downstream steps (e.g., final modifications and product export) into the second chassis strain.

- Interface Engineering: Implement cross-feeding mechanisms by engineering the production of essential metabolites or the export of pathway intermediates. Consider using:

- Validation: Co-culture the modules and verify:

- Intermediate transfer efficiency via LC-MS

- Final product titer compared to single-strain control

- Population stability over 5+ serial passages

Troubleshooting: If intermediate transfer is inefficient, consider engineering specialized transport systems or creating spatial proximity through immobilization in hydrogels or microfluidic devices [23].

Diagram Title: Modular Consortia Construction Workflow

Complex Substrate Utilization

Consolidated Bioprocessing Applications

Microbial consortia excel at deconstructing and utilizing complex substrates that are intractable for single strains, particularly in consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) of lignocellulosic biomass [2] [3]. Natural consortia achieve this through specialized DoL where different members produce complementary hydrolytic enzymes [3].

Table 2: Representative Synthetic Consortia for Complex Substrate Utilization

| Substrate | Consortium Members | Division of Labor Strategy | Product Output | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulosic biomass | Clostridium thermocellum + Thermoanaerobacter sp. | Cellulase production + hexose/pentose fermentation | Ethanol | 4.4-fold increase vs. monoculture [2] |

| Lignocellulose | Trichoderma reesei + Escherichia coli | Fungal cellulase secretion + bacterial biosynthesis | Isobutanol | 1.9 g/L, 62% theoretical yield [2] |

| Mixed sugars | Co-culture of specialized substrate utilizers | Catabolic resource partitioning | Biomass | >80% substrate consumption efficiency |

| Plastic polymers | Sequential degradation consortium | Primary degradation + intermediate assimilation | Degradation products | Enhanced complete mineralization |

Protocol: Consortium-Based Lignocellulose Deconstruction

Purpose: To establish a synthetic consortium for efficient lignocellulose deconstruction and conversion to valuable products.

Materials:

- Cellulolytic strain (e.g., Clostridium thermocellum, Trichoderma reesei)

- Product-forming strain (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, E. coli)

- Pretreated lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover, switchgrass)

- Anaerobic chamber (if using obligate anaerobes)

- Enzyme activity assays (e.g., endoglucanase, xylanase)

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Cultivate the cellulolytic and product-forming strains separately in optimized media to mid-exponential phase.

- Inoculum Optimization: Combine strains at varying ratios (e.g., 10:1, 1:1, 1:10 cellulolytic:product-forming) based on their relative growth rates and enzyme production capabilities.

- Bioreactor Setup: Inoculate the consortium into production media containing 2-5% (w/v) pretreated lignocellulosic biomass as the sole carbon source.

- Process Monitoring: Sample regularly to assess:

- Substrate degradation: DNS assay for reducing sugars

- Enzyme activities: Culture supernatant assays

- Population dynamics: Strain-specific qPCR or selective plating

- Product formation: HPLC for metabolites

- Process Optimization: Based on initial results, adjust:

- Oxygen transfer (critical for mixed aerobic/anaerobic systems)

- Nutrient supplementation to balance growth

- pH control to maintain enzyme activity

Key Considerations: The success of lignocellulose-degrading consortia depends on synchronizing the growth and metabolic activities of the partners. Implementing quorum sensing systems can help coordinate enzyme production with the capacity of the product-forming strain to utilize sugars [2] [21].

Essential Analytical Methods

Quantitative Microbial Community Analysis

Accurate quantification of absolute abundances is crucial for understanding population dynamics in DoL systems, as relative abundance data alone can be misleading [24] [25]. The table below compares key methodological approaches.

Table 3: Quantitative Methods for Consortia Analysis

| Method | Principle | Information Gained | Limitations | Compatibility with DoL Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA amplicon with dPCR anchoring | Digital PCR quantifies total 16S copies; normalizes sequencing data | Absolute taxon abundances; true population shifts | Requires optimization for different sample types; high host DNA may interfere | High - provides essential absolute abundance data [24] |

| Flow Cytometry with Cell Sorting | Physical counting and sizing of microbial cells | Total cell counts; cell size distributions | Cannot distinguish closely related strains; requires dissociation into single cells | Medium - good for total loads but limited taxonomic resolution |

| Metatranscriptomics | Sequencing of community RNA transcripts | Functional activity; pathway regulation | Requires high-quality RNA; difficult to attribute activity to specific strains | High - reveals functional DoL and metabolic interactions |

| Strain-Specific qPCR | Targeted amplification of unique genetic regions | Absolute abundance of specific engineered strains | Requires identification of unique marker sequences; multiplexing limitations | High - ideal for tracking defined synthetic consortia |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Genetic Manipulation of Microbial Consortia

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in DoL Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal QS Systems | lux, las, rpa, tra (HSL-based); agr (peptide-based) [21] | Enable coordinated gene expression across strains | Select systems with minimal cross-talk for independent communication channels |

| Genetic Toolkits | CRISPRi/a, modular plasmid vectors, promoter libraries | Pathway engineering and regulation | Use compatible systems for cross-species genetic manipulation |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, auxotrophic complementation, toxin-antitoxin | Maintain plasmid stability and strain ratios | Employ different markers for each consortium member |

| Metabolic Reporters | Fluorescent proteins, enzymatic reporters | Monitor population dynamics and gene expression | Use spectrally distinct fluorophores for simultaneous tracking |

| Cell Immobilization Matrices | Alginate beads, synthetic hydrogels, biofilms [23] | Spatial organization and population control | Tailor porosity for metabolite diffusion while containing cells |

| 3-Hydroxy-4',5-dimethoxystilbene | 3-Hydroxy-4',5-dimethoxystilbene, CAS:58436-29-6, MF:C16H16O3, MW:256.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tetrapentylammonium bromide | Tetrapentylammonium bromide, CAS:866-97-7, MF:C20H44BrN, MW:378.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram Title: Inter-strain Communication via QS

Computational Modeling and Design

Constraint-based metabolic modeling approaches, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and community-scale metabolic modeling, provide critical computational frameworks for predicting consortia behavior and optimizing DoL strategies [11]. These methods enable researchers to:

- Predict metabolic cross-feeding networks and potential bottlenecks

- Identify optimal pathway segmentation strategies

- Simulate population dynamics under different environmental conditions

- Design synthetic consortia with predefined functions

Protocol: Community-Level Metabolic Modeling

Purpose: To build and validate a genome-scale metabolic model of a synthetic consortium for DoL.

Materials:

- Annotated genomes of all consortium members

- Metabolic modeling software (e.g., COBRA Toolbox, Merlin)

- Physiological data (growth rates, substrate uptake, production rates)

Procedure:

- Model Reconstruction: Build or obtain genome-scale metabolic models for each individual strain.

- Community Integration: Create a compartmentalized community model with separate metabolic networks for each strain, connected through a shared extracellular space.

- Constraint Definition: Implement constraints based on experimental data:

- Strain-specific nutrient uptake rates

- Measured metabolic exchange rates

- Biomass composition for each strain

- Simulation and Prediction: Use appropriate algorithms (e.g., SteadyCom) to predict:

- Steady-state community composition

- Metabolic flux distributions

- Optimal DoL strategies for target compounds

- Experimental Validation: Compare model predictions with experimental results and iteratively refine the model.

The integration of computational modeling with experimental validation creates a powerful cycle for designing and optimizing consortia with enhanced robustness, modularity, and substrate utilization capabilities [11].

Tools and Techniques for Programming Functional Consortia

Genetic Manipulation Strategies for Consortium Engineering

Microbial consortia engineering represents a frontier in biotechnology that leverages division of labor to achieve complex functions impossible with single strains. This protocol details genetic manipulation strategies for designing, constructing, and optimizing synthetic microbial consortia, enabling precise control over community composition and function for applications ranging from bioproduction to bioremediation. We provide comprehensive methodologies for installing genetic circuits, optimizing metabolic pathways, and validating consortium performance through integrated design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles.

Microbial consortia engineering harnesses the principle of division of labor, where specialized community members collectively perform complex tasks more efficiently than individual strains [11]. This approach distributes metabolic burden, increases pathway efficiency, and enhances system robustness compared to monoculture engineering. The total metabolic capability of a community often exceeds the sum of its constituent members, enabling sophisticated applications in sustainable biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutic development [11].

Genetic manipulation of multispecies systems presents unique challenges, including cross-species compatibility of genetic parts, population stability maintenance, and emergent properties arising from microbial interactions. This protocol addresses these challenges through standardized workflows for consortia design, modular genetic toolkits, and analytical frameworks for community dynamics quantification.

Quantitative Foundations of Consortium Performance

Comparative Efficacy of Single-Strain vs. Consortium Inoculation

Meta-analyses of live-soil studies demonstrate the superior performance of microbial consortia across multiple metrics:

Table 1: Performance comparison of single-strain versus consortium inoculation

| Performance Metric | Single-Strain Inoculation | Microbial Consortium | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Enhancement | 29% increase | 48% increase | 65.5% higher |

| Pollution Remediation | 48% increase | 80% increase | 66.7% higher |

| Functional Stability | Reduced efficacy in field settings | Maintained significant advantage under various conditions | Enhanced environmental adaptability |

| Synergistic Effects | Limited to single-strain capabilities | Diversity and synergistic interactions contribute to effectiveness | Emergent properties |

The inoculant diversity and synergistic effects between complementary strains (e.g., Bacillus and Pseudomonas) significantly enhance consortium performance [26]. Optimal soil conditions for consortium inoculation include organic matter (6-7 pH), and adequate available N and P content [26].

Ecological Interactions in Engineered Consortia

Understanding ecological relationships is fundamental to consortium design:

Table 2: Ecological interaction types in microbial consortia

| Interaction Type | Effect on Species A | Effect on Species B | Engineering Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Positive | Positive | Stable co-culture systems |

| Commensalism | Neutral | Positive | Cross-feeding pathways |

| Amensalism | Negative | Neutral | Population control |

| Competition | Negative | Negative | Niche differentiation |

| Predation | Positive | Negative | Dynamic regulation |

These ecological interactions are often context-dependent, shaped by environmental factors, population densities, and surrounding species [27]. Engineering consortia with programmed social interactions enables control over population dynamics and enhances chemical production yields during fermentation [11].

Genetic Toolkits for Consortium Programming

Core Genetic Modification Technologies

Advanced genetic engineering techniques enable precise genome manipulations in consortium members:

Genetic Engineering Methods for Consortium Programming

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized microbial consortium engineering due to its high efficiency, multiplexing capability, and applicability across diverse microbial hosts [28]. Essential considerations for genetic modification include:

- Repair Pathway Selection: Nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) enables rapid gene knockouts, while homology-directed repair (HDR) allows precise sequence insertions [29]

- Host Compatibility: Genetic tool optimization for specific microbial hosts (e.g., Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria, yeast)

- Multiplexed Editing: Simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci to reduce iterative engineering cycles

Delivery Systems for Genetic Material

Effective delivery of genetic constructs is critical for consortium engineering:

- Plasmid-Based Systems: Broad-host-range vectors with compatible replication origins and selection markers

- Transposon Systems: PiggyBac transposase enables stable genomic integration in diverse microbial hosts [30]

- Viral Vectors: Bacteriophage-mediated delivery for specific bacterial taxa

- Conjugative Transfer: Leveraging bacterial mating systems for inter-strain DNA transfer

For stable transgene expression, vectors should incorporate constitutive promoters resistant to silencing (e.g., EF1α, PGK) rather than CMV-or LTR-driven expression, which can result in mosaicism [30]. Selection cassettes with antibiotics (puromycin, blasticidin, zeocin) or fluorescent reporters enable enrichment and tracking of engineered strains.

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Engineering

Protocol 1: Division of Labor Pathway Engineering

Objective: Implement complementary metabolic pathways across consortium members for enhanced bioproduction.

Materials:

- Microbial strains with compatible growth requirements

- Synthetic biology vectors with orthogonal genetic parts

- Selective media for each strain

- Microfermentation systems

Methodology:

Pathway Segmentation:

- Identify pathway bottlenecks and natural enzymatic compatibilities

- Divide pathway into modules based on metabolite toxicity, energy requirements, and regulatory complexity

- Design cross-feeding strategies for intermediate transfer between strains

Genetic Construction:

- Install pathway modules using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated integration

- Incorporate metabolite transporters for enhanced intermediate exchange

- Implement quorum sensing circuits for population balance regulation

Consortium Assembly:

- Initiate with balanced inoculum ratios (typically 1:1 to 1:5 depending on growth rates)

- Employ controlled bioreactor conditions with strain-specific selective pressures

- Monitor population dynamics via flow cytometry or fluorescent reporters

Validation:

- Quantify metabolite exchange rates via LC-MS

- Measure pathway flux using 13C metabolic flux analysis

- Assess production titers, yields, and productivities compared to monoculture systems

Protocol 2: Stable Consortium Maintenance Strategies

Objective: Maintain population stability and prevent strain dominance in engineered consortia.

Materials:

- Antibiotics for selective pressure

- Automated cell culture systems

- Fluorescent reporter tags

- Quantitative PCR equipment

Methodology:

Synthetic Interdependence Engineering:

- Design cross-feeding essential metabolites (amino acids, nucleotides, cofactors)

- Implement obligate mutualism through auxotrophies complemented by partner strains

- Create synthetic predator-prey systems for dynamic population control

Spatial Structuring:

- Encapsulate strains in semi-permeable membranes to control interaction rates

- Utilize microfluidic devices for compartmentalized co-culture

- Engineer biofilms with defined spatial organization

Dynamic Regulation:

- Install quorum sensing-controlled growth inhibition circuits

- Implement metabolite-responsive kill switches for population control

- Develop orthogonal communication channels for independent strain regulation

Long-Term Stability Assessment:

- Serial passage consortium for 50+ generations

- Monitor strain ratios via species-specific qPCR or fluorescence

- Sequence evolved populations to identify adaptive mutations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for genetic manipulation of microbial consortia

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Consortium Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Toolkits | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, TALENs, ZFNs | Targeted genome editing | Multispecies pathway engineering |

| Delivery Vectors | Broad-host-range plasmids, Conjugative systems | Genetic material transfer | Cross-species genetic manipulation |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, Fluorescent proteins, Metabolic markers | Strain selection and tracking | Population dynamics monitoring |

| Communication Systems | AHL-based quorum sensing, AIP systems | Inter-strain signaling | Coordinated behavior programming |

| Metabolic Modules | Cross-feeding pathways, Transporter systems | Metabolite exchange | Division of labor implementation |

| Stabilization Systems | Toxin-antitoxin pairs, Conditional essential genes | Population control | Consortium stability maintenance |

| 4-Nitrophenyl butyrate | 4-Nitrophenyl butyrate, CAS:2635-84-9, MF:C10H11NO4, MW:209.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (±)14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid | 14,15-EET|14,15-Epoxy-5,8,11-eicosatrienoic Acid | 14,15-Epoxy-5,8,11-eicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EET) is a high-purity epoxyeicosatrienoic acid for cardiovascular and cell signaling research. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Data-Driven Consortium Design

Advanced computational approaches enable predictive consortium design:

Data-Driven Consortium Design Workflow

The integration of multi-omics data with computational modeling enables predictive consortium design:

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling:

- Reconstruct metabolic networks for individual strains

- Predict cross-feeding opportunities and resource competition

- Identify optimal pathway segmentation for division of labor

Machine Learning Approaches:

- Analyze existing consortium data to identify design rules

- Predict interaction outcomes from genomic features

- Optimize strain combinations for target functions

Dynamic Simulations:

- Model population dynamics under different environmental conditions

- Predict system robustness to perturbations

- Identify stability bottlenecks before experimental implementation

Applications and Validation Metrics

Bioproduction Applications

Engineered consortia demonstrate particular advantage for:

- Complex Pathway Bioproduction: Division of labor reduces metabolic burden and improves titers of complex natural products

- Lignocellulosic Bioprocessing: Consolidated bioprocessing using specialized strains for different biomass components [11]

- Waste Valorization: Simultaneous utilization of mixed substrate streams

Performance Validation Framework

Essential metrics for consortium validation include:

- Population Stability: Strain ratios maintained over serial passages

- Functional Output: Target compound production rates and yields

- Robustness: Performance maintenance under environmental perturbations

- Genetic Stability: Preservation of engineered functions over time

Genetic manipulation of microbial consortia for division of labor research represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, enabling complex functions beyond single-strain capabilities. This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for designing, constructing, and validating engineered consortia through integrated genetic and computational approaches. As synthetic biology toolkits expand and our understanding of microbial interactions deepens, consortia engineering will increasingly address challenges in sustainable manufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutic development.

The iterative DBTL cycle—designing consortia based on ecological principles, building with advanced genetic tools, testing with appropriate metrics, and learning through multi-omics analysis—enables continuous improvement of consortium performance and functionality.

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia represents a frontier in synthetic biology, enabling complex tasks through a division of labor paradigm. A critical prerequisite for coordinating such multicellular systems is the establishment of robust, multi-channel cell-cell communication. Orthogonal quorum sensing (QS) systems provide the foundational "wiring" for this coordination, allowing independent communication channels to operate concurrently without cross-activation (crosstalk). This application note details the design principles, quantitative characterization, and implementation protocols for orthogonal QS systems, providing a toolkit for advanced genetic manipulation of microbial consortia.

The Need for Orthogonality in Microbial Communication

Natural QS systems, while diverse, often exhibit significant crosstalk due to the structural similarity of their acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signal molecules and the promiscuity of their cognate transcription factors [31] [32]. This crosstalk manifests as a single AHL activating multiple non-cognate receptors or a single receptor responding to multiple non-cognate AHLs, leading to faulty gene circuit operation [33] [34]. The engineering of complex consortia requiring multiple independent communication channels necessitates systems with high orthogonality—where a sender synthase activates only its intended receiver transcription factor among all others present [32]. Achieving this requires a combination of careful component selection, promoter engineering, and directed evolution to insulate channels from one another [31].

Orthogonal Quorum Sensing System Toolbox

De Novo Designed Systems from Diverse Small Molecules

Moving beyond conventional AHLs, a de novo design approach leveraging the chemical diversity of biological small molecules has yielded six high-performance, orthogonal communication channels in Escherichia coli [31]. These systems were built by designing biosynthetic pathways for novel signal molecules from universal cellular metabolites and engineering their corresponding sensing apparatus.

Table 1: De Novo Designed Orthogonal Signaling Systems

| Signal Molecule | Sensing Transcription Factor | Dynamic Range (Fold) | Key Biosynthetic Genes | Precursor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salicylate (Sal) | NahR | 1380 | pchBA or irp9 | Chorismate |

| 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) | PhlF | 1380 | phlACBDE | Malonyl-CoA |

| Isovaleryl-HSL (IV) | BjaR | 350 | bdkFGH, IpdA1, bjaI | Isoleucine |

| p-Coumaroyl-HSL (pC) | RpaR | 170 | tal, rpaI | Tyrosine |

| Methylenomycin furan (MMF) | MmfR | 26 | mmfL | Not Specified |

| Naringenin (NG) | Not Specified | 16 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Engineered AHL Systems with Validated Orthogonality

Extensive characterization of AHL synthase-regulator pairs has identified specific combinations that exhibit minimal crosstalk. These systems provide a set of modular, well-characterized parts for consortium engineering.

Table 2: Orthogonal AHL Synthase-Regulator Pairs [33] [34]

| Orthogonal Set | Synthase | Regulator | Primary AHL Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | BjaI | BjaR | Isovaleryl-HSL (IV) |

| EsaI | TraR | 3-Oxo-C8-HSL | |

| Set 2 | LasI | LasR | 3-Oxo-C12-HSL |

| EsaI | TraR | 3-Oxo-C8-HSL | |

| Fully Optimized System | LasI (Optimized) | LasR (Optimized) | 3-Oxo-C12-HSL |

| TraI (Optimized) | TraR (Optimized) | 3-Oxo-C8-HSL |