Engineering Stable Alliances: Strategies for Robust Synthetic Microbial Consortia in Biomedicine

Synthetic microbial consortia (SyMCon) represent a paradigm shift in biotechnology, offering superior functionality over single-strain applications by distributing metabolic tasks and enhancing resilience.

Engineering Stable Alliances: Strategies for Robust Synthetic Microbial Consortia in Biomedicine

Abstract

Synthetic microbial consortia (SyMCon) represent a paradigm shift in biotechnology, offering superior functionality over single-strain applications by distributing metabolic tasks and enhancing resilience. However, their therapeutic potential in drug development is often limited by ecological instability. This article synthesizes the latest research to provide a comprehensive framework for improving SyMCon stability. We explore the foundational principles of microbial interactions, detail advanced methodological strategies for design and assembly, present troubleshooting and optimization techniques grounded in systems biology, and discuss validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review bridges ecological theory and practical engineering to enable the creation of robust, predictable, and effective microbial consortia for next-generation biomedical applications.

The Blueprint of Stability: Core Principles and Ecological Interactions in Synthetic Consortia

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Core Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What are the different dimensions of stability in Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs)? Stability in SynComs is a multi-faceted concept. The key dimensions include [1]:

- Resistance: The ability of the community to withstand a disturbance without significant shifts in its composition or function.

- Resilience: The capacity of the community to recover its original structural organization and functional performance after a perturbation.

- Robustness: The overarching ability to maintain both structure and function in the face of environmental fluctuations and disturbances. It is crucial to note that stability can refer to the persistence of species composition or the retention of community function, and these do not always align [1].

Q2: What are the main strategies for constructing a stable SynCom? There are two primary engineering strategies for constructing SynComs, each with distinct advantages and challenges [2] [3]:

- Top-Down Strategy: This involves assembling a stable co-culture system from multiple, defined microbial strains based on known principles (e.g., metabolic networks). While it allows for precise control, it can face challenges in long-term community regulation, as competition for resources often leads to one species dominating others [2] [3].

- Bottom-Up Strategy: This method starts with a natural microbial community and applies environmental filters (e.g., continuous enrichment or serial dilution in a bioreactor) to select for a minimal active microbial consortia (MAMC). These consortia may have better temporal stability but their acquisition can be random and difficult to direct [2] [3]. A Multi-Strategy approach that combines both methods is increasingly used to mitigate the limitations of each single strategy [2] [3].

Q3: How do microbial interactions affect SynCom stability? Interspecies interactions are fundamental to community dynamics and stability [1].

- Positive Interactions (Mutualism, Commensalism): These often emerge from metabolic cross-feeding, where the exchange of metabolic byproducts enhances overall community efficiency and resilience. Engineering these interactions can superior functional performance [1].

- Negative Interactions (Competition, Antagonism): These occur through competition for limited resources (nutrients, space) or via chemical warfare (e.g., antibiotic production). While intense competition can destabilize a community, strategic manipulation, such as introducing a third competitor, can sometimes enhance stability [1].

- Cheating Behavior: This is a critical challenge where some members exploit shared resources without contributing, potentially leading to the collapse of mutualistic partnerships. Incorporating spatial organization into community design is a key strategy to suppress cheating [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My SynCom collapses, with one strain outcompeting all others. How can I prevent this?

- Problem: Dominance by a single strain due to uncontrolled competition.

- Solution:

- Engineer Cross-Feeding Interdependencies: Design the community so that strains rely on each other for essential metabolites. This creates a mutualistic network where the success of one depends on the others, promoting stable coexistence [1] [2].

- Utilize Spatial Structuring: Use bioreactors or culturing conditions that create physical heterogeneity (e.g., biofilms, microencapsulation). Spatial segregation can reduce direct competition for resources and protect cooperative interactions from cheaters [1].

- Apply Evolutionary Pressure: Use directed evolution or serial passaging under conditions that favor the desired community function. This can select for strains that have adapted to coexist stably over the long term [1] [3].

Q2: The community maintains its species composition, but the desired function is lost over time.

- Problem: Functional decay despite compositional permanence.

- Solution:

- Monitor Functional Output: Shift your stability assessment from tracking only species abundance to directly measuring the functional output of the community (e.g., metabolite production, degradation rates) over time [1].

- Check for Cheaters: Identify if non-productive "cheater" strains are thriving. If so, employ spatial structuring or introduce environmental conditions that penalize cheating behavior [1].

- Ensure Metabolic Balance: Re-examine the resource partitioning and metabolic loads. The division of labor may need re-optimization to prevent the buildup of toxic intermediates or the exhaustion of critical precursors [1] [2].

Q3: My SynCom performs well in the lab but fails when introduced into the target environment (e.g., soil, gut).

- Problem: Lack of ecological resilience in a complex, natural environment.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Native Keystone Species: Include carefully selected members from the native microbial community of the target environment. These keystone species are adapted to the local conditions and can help govern the overall structure and function of the consortium [1].

- Pre-adaptation through Directed Evolution: Prior to application, evolve your SynCom under conditions that simulate key aspects of the target environment (e.g., temperature cycles, nutrient gradients). This selects for variants with enhanced fitness and resilience in those conditions [3].

- Employ a Bottom-Up Enrichment Strategy: Instead of a fully synthetic top-down assembly, start with a natural community from the target environment and enrich for the desired function. The resulting MAMC may be pre-adapted and thus more stable [2] [3].

Quantitative Data on SynCom Stability and Performance

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different SynCom Construction Strategies

| Construction Strategy | Example Application | Key Result | Stability & Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down | Alkane (diesel, crude oil) degradation by Acinetobacter sp. XM-02 and Pseudomonas sp. [2] | Degradation rate reached 97.41%, which was 8.06% higher than the pure bacteria system [2]. | Performance enhanced by division of labor; long-term structural stability can be a challenge [2] [3]. |

| Top-Down | Degradation of the herbicide bispyribac sodium (BS) by a three-strain consortium [2] | Maximum BS degradation reached 85.6% [2]. | Demonstrates efficacy for specific bioprocessing tasks. |

| Bottom-Up | Lignin degradation by a five-species consortium [2] | Lignin degradation rate was up to 96.5% [2]. | Co-evolved consortia may have better temporal stability and functional redundancy [2]. |

| Bottom-Up | Lignocellulose and chlorophenol degradation by Paenibacillus sp. and Pseudomonas sp. [2] | 75% of chlorophenol degraded after 9 days; 41.5% of straw degraded after 12 days [2]. | Shows capacity for simultaneous, complex degradation processes. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Stability Issues in SynComs

| Observed Problem | Potential Ecological Cause | Recommended Experiments for Diagnosis | Proposed Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Collapse / Dominance | Unchecked competition; Lack of positive interactions [1]. | Measure growth curves in mono- vs co-culture; Screen for antimicrobial activity [1]. | Engineer obligate cross-feeding; Introduce spatial structure [1]. |

| Functional Drift / Loss | Emergence of cheaters; Metabolic burden; Evolutionary trade-offs [1]. | Track functional metabolites and population dynamics; Sequence evolved communities to identify mutations [1]. | Implement selective pressure for function; Re-balance metabolic loads; Use evolution-guided design [1]. |

| Poor Environmental Resilience | Inadequate resistance/resilience to abiotic factors (pH, temp); Exclusion by native microbiota [1]. | Challenge consortium with simulated environmental stresses; Conduct invasion assays with native species [1]. | Pre-adapt consortium via directed evolution; Include native keystone species [1] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Stability and Functional Tracking

Objective: To simultaneously monitor the compositional stability and functional output of a SynCom over time. Methodology:

- Setup: Establish triplicate co-cultures of your SynCom in the desired medium and environmental conditions.

- Sampling: At defined intervals (e.g., every 24-48 hours over 7-15 days), aseptically remove samples from each culture.

- Compositional Analysis (DNA): Extract genomic DNA from each sample. Perform 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing or strain-specific qPCR to quantify the abundance of each member.

- Functional Analysis (Metabolomics/Activity):

- For production consortia: Use HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the concentration of the target metabolite or product in the culture supernatant.

- For degradation consortia: Use spectrophotometric or chromatographic assays to measure the concentration of the target pollutant/substrate.

- Data Integration: Plot species abundance and functional output against time to visualize correlations between composition and function [1].

Protocol 2: Assessing Resistance to a Perturbation

Objective: To quantify the community's ability to withstand a disturbance. Methodology:

- Establish Baseline: Grow the SynCom to a steady state.

- Apply Perturbation: Introduce a defined disturbance. Examples include:

- Antibiotic Pulse: Add a sub-inhibitory concentration of a relevant antibiotic.

- pH Shift: Adjust the pH of the medium by a defined value (e.g., 1.0 unit).

- Species Invasion: Introduce a small amount of a foreign, non-consortium strain.

- Monitor: Sample immediately before the perturbation (T=0) and at regular intervals after. Perform compositional and functional analysis as in Protocol 1.

- Calculate Resistance: The resistance can be quantified as the degree of change in composition/function at a specific time point post-perturbation relative to the baseline state [1].

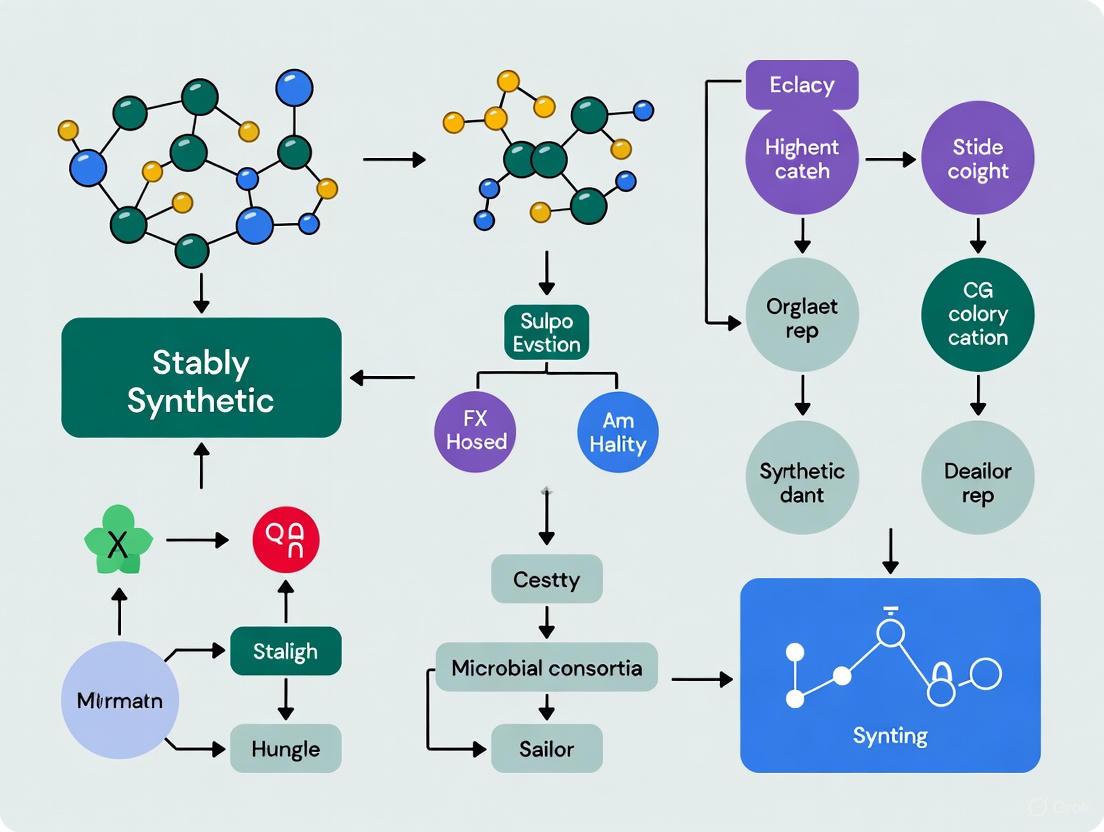

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

DBTL Cycle

Interaction Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for SynCom Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Computational prediction of metabolic interactions, resource partitioning, and potential cross-feeding within a designed consortium [1]. | Constrained with multi-omics data to improve predictive accuracy for community behavior [1]. |

| Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) Prediction Tools | In silico genomic screening to identify potential for antagonistic interactions (e.g., antibiotic production) between prospective consortium members [1]. | Helps minimize negative interactions during the initial design phase by avoiding strain pairs with high BGC overlap [1]. |

| High-Throughput Culturomics Platforms | Isolation and cultivation of previously uncultured microorganisms, expanding the available strain library for bottom-up and top-down construction [1]. | Techniques include in situ culture, microfluidics, and cell sorting to access microbial "dark matter" [1]. |

| Automated Bioreactor Systems | Precise, high-throughput cultivation and testing of SynCom variants under controlled or dynamically changing environmental conditions [1]. | Enables efficient DBTL cycles and directed evolution experiments [3]. |

| Multi-omics Analysis Suites | Integrated analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic, and proteomic data from SynComs to decipher mechanistic interactions and functional outcomes [1]. | Critical for the "Learn" phase of the DBTL cycle, informing model refinement [1]. |

| VV261 | VV261, MF:C28H34FN3O11, MW:607.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Harman | Harman, CAS:21655-84-5; 486-84-0, MF:C12H10N2, MW:182.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

During microbial applications, metabolic burdens can lead to a significant drop in cell performance, a phenomenon known as the "metabolic cliff" [4]. This fundamental limitation of single-strain engineering occurs when hosts must allocate limited resources among competing tasks, causing reduced biochemical productivity and increased susceptibility to stress [4]. Synthetic microbial consortia—ecosystems of rationally designed microorganisms—offer a powerful alternative by distributing metabolic tasks across multiple specialized strains [5].

These consortia demonstrate three fundamental advantages: division of labor that partitions complex pathways into manageable segments, reduced metabolic burden on individual strains, and enhanced evolutionary robustness through functional redundancy [6]. This technical guide explores these advantages through a troubleshooting lens, providing experimental methodologies and practical solutions for researchers aiming to improve consortium stability for pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications.

Core Advantages: Quantitative Comparisons

The theoretical benefits of microbial consortia are supported by empirical data across multiple applications. The table below summarizes key performance metrics demonstrating the advantages of consortia over single-strain approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison: Single Strains vs. Microbial Consortia

| Application | Single Strain Performance | Consortium Performance | Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isobutanol from Biomass | Low yield in single engineered strain | 1.9 g/L (using T. reesei and E. coli) | 62% of theoretical maximum yield | [4] |

| Oxygenated Taxanes | Challenging in single host | Efficient production (using E. coli and S. cerevisiae) | Expanded metabolic capability | [7] |

| n-Butanol from Cellulose | Low titers in single organism | 3.73 g/L (using C. celevecrescens and C. acetobutylicum) | Enabled consolidated bioprocessing | [4] |

| Artemisinin Precursor | ~0.19 g/L in monoculture | 2.8 g/L (using S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris) | 15-fold improvement | [8] |

| Bioethanol Production | Lower yield in monoculture | 40% increase (using S. cerevisiae and C. autoethanogenum) | Mitigated redox imbalances | [8] |

| Alkane Degradation | Moderate degradation efficiency | 8.06% higher degradation rate | Surfactant production enhanced access | [3] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Unstable Population Dynamics

Problem: One species consistently outcompetes others, leading to rapid collapse of the desired community structure and function [4].

Solutions:

- Optimize Inoculation Ratios: Systematically test different initial ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:10, 10:1) to identify conditions that extend co-culture stability [4].

- Implement Nutritional Divergence: Engineer strains to utilize different carbon sources or essential nutrients to reduce direct competition [4].

- Employ Quorum Sensing (QS) Feedback: Construct genetic circuits where population density triggers control mechanisms. For example, program a strain to produce a toxin when its population exceeds a threshold [9] [6].

- Utilize Cell Immobilization: Co-culture free cells with immobilized partners (e.g., Pichia stipites with immobilized Zymomonas mobilis for ethanol production) to physically stabilize populations [4].

Experimental Protocol: Population Stability Assay

- Inoculate co-cultures at varying ratios in minimal medium.

- Sample populations every 2-4 hours using flow cytometry (with fluorescent markers) or selective plating.

- Calculate population doubling times and carrying capacities for each strain.

- Model dynamics using tools like COMETS (Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Space and Time) to predict long-term stability [7].

- Iteratively refine conditions based on model predictions.

Challenge: Metabolic Burden in Pathway Expression

Problem: Expression of complex heterologous pathways overwhelms cellular resources, reducing growth and productivity [4] [6].

Solutions:

- Distribute Pathway Modules: Partition biosynthetic pathways between strains based on their native metabolic strengths. For example, produce taxadiene in E. coli and perform oxidation steps in S. cerevisiae to leverage eukaryotic cytochrome systems [7].

- Implement Metabolic Cross-Feeding: Design syntrophic interactions where one strain consumes the byproducts of another. This can be achieved by engineering auxotrophies that create obligate mutualisms [7] [5].

- Dynamic Pathway Regulation: Use QS systems to delay expression of burdensome pathways until high cell density is achieved [6].

Experimental Protocol: Burden Distribution Validation

- Split target pathway into modules at points with stable, transportable intermediates.

- Engineer each module into separate chassis with appropriate promoters and regulators.

- Measure growth rates and plasmid retention for each strain alone and in co-culture.

- Quantify intermediate transport and final product titers.

- Use RNA sequencing to identify stress responses and further optimize expression levels.

Challenge: Inefficient Inter-Species Communication

Problem: Engineered communication systems exhibit crosstalk or insufficient signal strength, leading to poor coordination [6].

Solutions:

- Employ Orthogonal QS Systems: Use multiple, non-interfering QS systems such as lux, las, rpa, and tra systems in Gram-negative bacteria, or autoinducing peptides in Gram-positive bacteria [6].

- Amplify Signal Production: Increase signal molecule production by using strong constitutive promoters upstream of synthase genes (e.g., luxI, lasI) [9].

- Enhance Signal Detection: Modify receiver strains by increasing receptor expression or using high-sensitivity promoter variants to improve detection thresholds [10].

Experimental Protocol: Communication Circuit Characterization

- Transform sender strains with constitutive signal synthase expression.

- Transform receiver strains with signal-responsive promoters driving fluorescent reporter expression.

- Co-culture senders and receivers at different ratios and measure response dynamics.

- Quantify signal molecule concentrations using LC-MS or bioassays.

- Test for crosstalk by exposing receivers to non-cognate signals.

dot Experimental Workflow for Consortium Design and Troubleshooting

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful consortium engineering requires specialized genetic tools and reagents. The table below outlines key solutions for constructing and maintaining synthetic microbial communities.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Consortia Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing Systems | LuxI/LuxR (3OC6-HSL), LasI/LasR (3OC12-HSL), orthogonal Rpa/Tra systems | Enable density-dependent communication and coordination between strains | Test for crosstalk; match signal permeability with cultivation format | [9] [6] |

| Toxin-Antitoxin Systems | CcdB/CcdA (E. coli), MazF/MazE | Implement population control or negative interactions; enable amensalism/competition topologies | Balance expression levels to avoid complete population collapse | [9] [5] |

| Metabolic Auxotrophies | Amino acid (e.g., methionine, leucine), vitamin, or nucleotide auxotrophies | Create obligate mutualisms and stabilize consortia through metabolic cross-feeding | Ensure efficient metabolite transport between strains | [7] [5] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, mRFP, YFP with orthogonal promoters | Track population dynamics in real time without destructive sampling | Select spectrally distinct fluorophores with minimal fitness cost | [9] |

| Inducible Promoters | IPTG-inducible (Plac/lux), ATC-inducible (Ptet/las) | Provide external control for tuning gene expression and population behaviors | Use orthogonal inducers to independently control multiple strains | [9] [6] |

| Modeling Software | COMETS, FBA (Flux Balance Analysis), Machine Learning algorithms | Predict community dynamics, metabolic exchanges, and optimal design parameters | Integrate experimental data to improve model accuracy | [7] [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: How can I prevent "cheater" strains that benefit from the consortium without contributing to its function?

- Implement essential cross-feeding where each strain depends on others for survival metabolites [7]. Use QS-controlled essential gene expression so that strains must communicate to activate their own growth programs [6]. Consider spatial structuring using microfluidic devices or biofilms to create local environments where cooperation is favored [7].

Q2: What are the best practices for storing and reviving synthetic consortia?

- Cryopreserve aliquots at standardized cell ratios in glycerol stocks. Avoid repeated serial passage, which can alter population balance. After revival, validate population structure through selective plating or flow cytometry before use in experiments [4].

Q3: How can I measure metabolic burden in consortium members?

- Monitor growth rates and plasmid retention of each strain alone versus in consortium. Use RNA sequencing to identify stress response pathways. Measure ATP and NADPH levels as indicators of metabolic state [4]. Compare these metrics to single-strain controls expressing full pathways.

Q4: What computational approaches best predict consortium behavior?

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) models metabolic exchanges in steady-state conditions [7]. COMETS incorporates spatial and temporal dynamics for more realistic predictions [7]. Recently, machine learning models trained on multi-omics data have shown promise in predicting community dynamics and optimizing production conditions [11] [8].

dot Microbial Consortia Signaling and Control Pathways

Synthetic microbial consortia represent a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, offering solutions to fundamental limitations of single-strain approaches. By strategically implementing division of labor, managing metabolic burden through pathway partitioning, and designing robust interaction networks, researchers can create stable, high-performance communities. The troubleshooting guidelines and experimental protocols provided here address key technical challenges in consortium development, enabling more reliable construction of microbial ecosystems for pharmaceutical and industrial applications. As synthetic biology tools advance, particularly in modeling and genetic circuit design, the precision and scalability of these approaches will continue to improve, opening new frontiers in bioproduction and therapeutic applications.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental types of interactions in a synthetic microbial consortium? Synthetic microbial consortia are characterized by three primary types of interactions, which dictate community stability and function:

- Cross-feeding (Cooperation): A form of metabolic cooperation where one strain produces a metabolite that serves as a substrate for another strain. This can be unidirectional or bidirectional, fostering stable interdependence [12].

- Competition: An interaction where multiple strains within the community compete for shared, limited resources such as nutrients or space. Unchecked competition can lead to the collapse of the consortium [12] [13].

- Predation/Amensalism: Interactions where one organism benefits at the expense of another, for example, through the production of antimicrobial compounds [13]. Engineering these interactions can enhance community stability.

FAQ 2: My consortium is unstable, with one strain consistently outcompeting others. How can I stabilize it? This is a common issue often caused by uncontrolled competition. You can address it by:

- Engineering Obligate Mutualism: Genetically modify strains to create cross-feeding dependencies where each strain relies on the other for an essential nutrient or metabolic intermediate, making coexistence necessary [14].

- Spatial Structuring: Use solid supports or microencapsulation to create physical niches. This reduces direct competition for space and resources, allowing slower-growing but functionally critical strains to persist [14].

- Modular Design: Adopt a modular approach where the complex metabolic pathway is split between different strains. This divides the metabolic burden and can prevent any single strain from gaining a dominant fitness advantage [15] [11].

FAQ 3: Are there computational tools to predict interactions before I start lab experiments? Yes, computational modeling can significantly reduce experimental workload.

- Metabolic Network Modeling: Tools like CarveMe can automatically reconstruct genome-scale metabolic models from microbial genomes. These models simulate the metabolic flow and can predict potential cross-feeding and competition over nutrients [12].

- Machine Learning Prediction: A novel method uses features from automatically reconstructed metabolic networks to train machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost). These models can predict whether a pair of bacteria will exhibit cross-feeding or competition with high accuracy, helping you pre-select compatible strains [12].

- Individual-based Models (IbM): These computational models simulate the actions and interactions of individual microbes to predict the emergent behavior of the whole community, providing insights into population dynamics [11].

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Cross-feeding Community for Targeted Metabolite Production

The following detailed methodology is based on a study that successfully constructed a synthetic community for the efficient production of guaiacols [15].

Strain Isolation and Identification

- Sample Collection: Collect fermented grains from a relevant source. Ensure samples are mixed thoroughly for representativeness. Store samples at 4°C for immediate isolation and at -80°C for DNA extraction.

- Microbial Isolation: Isolate strains using standard culture techniques on appropriate media. A typical yield might be 67 strains, including bacteria, yeasts, and molds [15].

- Phylogenetic Identification: Identify isolates by sequencing their 16S rDNA (for bacteria) or ITS regions (for fungi). Construct a phylogenetic tree to visualize genetic relationships.

Screening for Functional Strains

- Single-Strain Fermentation: Ferment each isolated strain individually in a medium containing the target precursor (e.g., ferulic acid).

- Metabolite Analysis: Use Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or similar techniques to analyze the fermentation products. Identify strains responsible for producing the target product (e.g., 4-ethylguaiacol) and key intermediates (e.g., 4-vinylguaiacol) [15].

Consortium Construction and Assembly

- Modular Assembly: Adopt a division-of-labor strategy. Assemble the community using different functional modules:

- Module A (Converter): A strain that efficiently converts the precursor (ferulic acid) to an intermediate (4-vinylguaiacol).

- Module B (Reducer): A strain that efficiently converts the intermediate (4-vinylguaiacol) to the final product (4-ethylguaiacol) [15].

- Co-cultivation: Inoculate the selected strains together in a controlled bioreactor. Monitor community dynamics and metabolite production over time.

Validation and Interaction Analysis

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Track the population dynamics of each strain within the consortium throughout the fermentation process to ensure stable coexistence.

- Metabolite Profiling: Regularly sample the culture broth to quantify the concentrations of the precursor, intermediate, and final product, confirming the designed metabolic pathway is functioning as intended [15].

Key Concepts and Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for building a synthetic microbial consortium.

Diagram 2: Logical relationships between interaction types, stability, and engineering strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for synthetic consortium research.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analyzing volatile metabolites and flavor compounds produced by the consortium. | Used to quantify guaiacols (4-EG, 4-VG) in a synthetic community [15]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Tracking absolute abundance and population dynamics of individual strains within a co-culture. | Method for monitoring the stability of strain ratios in a constructed community [15]. |

| CarveMe | Automated computational tool for reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models from an organism's genome. | Used to predict potential cross-feeding and competition interactions between bacterial pairs [12]. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) | Predicting interaction types (cross-feeding/competition) between microbes based on metabolic network features. | Achieved >90% accuracy in predicting bacterial interactions, reducing experimental screening load [12]. |

| Synthetic Genetic Circuits | Genetically engineering obligate mutualism by making strains dependent on exchanged metabolites. | Used to enforce stability in a multi-strain system [14]. |

| Amantadine | Amantadine, CAS:665-66-7; 768-94-5, MF:C10H17N, MW:151.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-107 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-107, MF:C15H11FO4, MW:274.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) and Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) in Coexistence

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are MRO and MIP, and why are they critical for consortium stability? MRO (Metabolic Resource Overlap) quantifies the similarity in nutritional requirements between different microbial strains. A high MRO indicates intense competition for resources, which can destabilize a community [16] [17]. MIP (Metabolic Interaction Potential) measures the potential for mutualistic metabolic exchanges, such as cross-feeding, where one species produces a metabolite that another requires. A high MIP fosters cooperation and enhances community stability [16] [17]. The core principle for designing stable consortia is to minimize MRO and maximize MIP [17].

2. How can I predict MRO and MIP for my candidate strains? The standard method is to use Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GMM). This involves reconstructing metabolic models for each strain based on their genome sequences. These models can then be used to calculate the overlap in minimal nutritional requirements (MRO) and to simulate potential cross-feeding interactions (MIP) [18] [16] [17]. Tools like the ModelSEED pipeline can facilitate this reconstruction [16].

3. I've built a community with high MIP, but it remains unstable. What could be wrong? Environmental context is crucial. A high MIP value indicates a potential for interaction, but these dependencies may not manifest if the environment is nutrient-rich. Metabolic cross-feeding is often more critical for survival in nutrient-poor conditions [16]. Re-evaluate your growth medium; stability may improve under more restrictive nutritional conditions that force interdependence.

4. Are there specific types of strains that enhance community stability? Yes. Research shows that including narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) strains—those with specialized metabolic capabilities—can significantly improve stability. These strains typically have lower MRO with neighbors and act as central nodes in the cross-feeding network, thereby increasing the overall MIP of the consortium [17]. In contrast, broad-spectrum utilizers often increase competitive pressure [17].

5. The phyllosphere study found weak competition effects in planta. Does this mean MRO is not important in real environments? Not at all. It highlights the role of spatial heterogeneity. On leaf surfaces, resources are patchily distributed, which can mitigate direct competition by physically separating microbes [18]. Your experimental system (e.g., in vitro liquid culture vs. a structured biofilm or plant surface) will strongly influence the outcome. MRO is a key driver, but its effect can be modulated by the habitat's physical structure.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Quantifying MRO and MIP via Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling

This protocol allows for the in silico prediction of competition and cooperation potentials before embarking on costly wet-lab experiments [16] [17].

Step 1: Genome Acquisition and Metabolic Reconstruction Obtain high-quality genome sequences for your candidate microbial strains. Use a pipeline like ModelSEED to automatically reconstruct draft genome-scale metabolic models (GMMs) for each organism [16]. Manually curate models using phenotypic array data (e.g., from Biolog plates) to improve accuracy by removing spurious metabolic capabilities [16] [17].

Step 2: Define a Minimal Medium The calculations for MRO and MIP are typically performed in the context of a defined minimal medium to clearly identify essential dependencies. The composition should be relevant to your target habitat (e.g., plant rhizosphere or human gut).

Step 3: Calculate Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) MRO is computed as the maximum possible overlap between the minimal nutritional requirements of all member species in a community [16]. This is an intrinsic property of the group of strains, representing an upper bound on resource competition.

Step 4: Calculate Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) MIP is defined as the maximum number of essential nutrients that a community can synthesize internally through interspecies metabolic exchanges [16]. This metric quantifies the community's potential for metabolic cooperation and self-sufficiency.

Step 5: Community Simulation Combine the individual metabolic models into a community model. Use a method like SMETANA (Species METabolic Interaction AnAlysis) to systematically enumerate all possible metabolic exchanges that are essential for the survival of the community in your defined minimal medium [16].

Protocol 2:In PlantaPairwise Competition Assay

This protocol validates the predictions from metabolic modeling in a realistic, spatially structured environment like the phyllosphere (leaf surface) [18].

Step 1: Strain Preparation Use a model epiphytic bacterium like Pantoea eucalypti 299R (Pe299R) as the focal strain. Engineer it to constitutively express a fluorescent protein (e.g., mScarlet-I) for detection. Competitor strains should be selected based on their phylogenetic distance and predicted MRO with the focal strain.

Step 2: Plant Inoculation Grow Arabidopsis thaliana plants under controlled conditions. Inoculate leaves with a suspension of the focal strain and a competitor strain, either separately or in a mixture. Use a buffer like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for the suspension and inoculation.

Step 3: Incubation and Sampling Incubate inoculated plants under conditions of high humidity. Sample leaf disks at defined time points post-inoculation (e.g., 0, 24, 48 hours).

Step 4: Population Density Assessment Homogenize the leaf disks and plate serial dilutions onto selective media to enumerate the population densities (in CFU/g of leaf) of both the focal and competitor strains.

Step 5: Single-Cell Reproductive Success Analysis (Optional) For higher-resolution data, use a bioreporter system like CUSPER in the focal strain. This system dilutes a fluorescent protein upon cell division, allowing you to track the reproductive history of individual bacterial cells on the leaf surface using microscopy [18].

The table below consolidates critical data on how MRO and MIP influence community outcomes, drawn from recent studies.

Table 1: The Impact of Metabolic Metrics on Community Stability and Function

| Study Context | Metric | Key Quantitative Finding | Impact on Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Plant-Beneficial Community [17] | MRO | A positive correlation was found between a strain's resource utilization width and its MRO (R² = 0.3465, p < 0.001). | Higher competition, reduced stability. |

| Synthetic Plant-Beneficial Community [17] | MIP | A negative correlation was found between a strain's resource utilization width and its contribution to MIP (R² = 0.4901, p < 0.0001). | Narrow-spectrum utilizers enhanced cooperation potential. |

| Natural Communities Survey [16] | MRO | Sample communities featured significantly higher resource competition than random assemblies (P < 0.05). | Highlights role of habitat filtering in assembly. |

| Natural Communities Survey [16] | MIP | Co-occurring subcommunities had significantly higher MIP than random controls (P < 10â»Â¹âµ for quadruplets). | Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence. |

| Phyllosphere Competition [18] | Resource Overlap | Effects of resource competition were much weaker in the phyllosphere than in vitro. | Spatial heterogeneity mitigates competition. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MRO/MIP Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| ModelSEED Pipeline | A bioinformatics platform for the automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models from genome sequences. | Used to reconstruct models for 261 species in a large-scale community survey [16]. |

| SMETANA Algorithm | A computational method to identify and quantify metabolic interactions (cross-feeding) within a microbial community. | Employed to predict metabolic exchanges in over 800 microbial communities [16]. |

| Pantoea eucalypti 299R | A well-characterized model epiphytic bacterium frequently used in phyllosphere ecology and competition studies. | Used as a focal strain to study the impact of resource overlap with six different competitors [18]. |

| CUSPER Bioreporter | A genetic construct that reports on the number of cell divisions based on the dilution of a fluorescent protein. | Enabled the measurement of single-cell reproductive success of bacteria in the heterogeneous phyllosphere [18]. |

| Minimal Media (MM) | A defined growth medium with known carbon sources, used to assess core metabolic capabilities and interactions. | Crucial for in vitro growth assays and for defining the constraints in metabolic models [18]. |

| R2A Agar/Broth | A nutrient-rich growth medium used for the routine cultivation of a wide variety of environmental bacteria. | Served as a general non-selective medium for growing bacterial strains before competition experiments [18]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the integrated theoretical and experimental workflow for designing and validating a stable synthetic microbial consortium.

Integrated Workflow for Consortium Design

The logical relationships between strain characteristics, metabolic metrics, and community outcomes are summarized below.

Strain Traits and Community Outcomes

From Theory to Therapy: Design Strategies and Assembly of Stable Synthetic Communities

Within the broader objective of improving the stability of synthetic microbial consortia, top-down microbiome engineering serves as a powerful strategy. This approach simplifies complex natural communities by applying selective pressures to steer them toward a desired function, such as waste valorization or pollutant degradation [19] [20]. It operates on the principle of using environmental variables as tools to guide an existing microbiome through ecological selection, rather than designing it from individual parts [2] [21]. While this method can yield streamlined, high-performing consortia, researchers often face challenges related to community stability, functional predictability, and process control. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you navigate these specific issues.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What is a top-down approach in microbiome engineering?

A top-down approach is a classical method that uses selective pressure by manipulating environmental or operating conditions to steer the structure and metabolic activity of a natural microbial consortium toward a desired function [19] [20]. Instead of building a community from isolated parts, you start with a complex natural inoculum (e.g., from soil, sediment, or a reactor) and apply specific, controlled environmental conditions. This encourages the growth and activity of microorganisms that contribute to your target process, while less functional members are outcompeted, leading to a simplified, optimized community [2] [22].

FAQ 2: What are common selective pressures used in top-down enrichment?

You can manipulate a variety of environmental variables to exert selective pressure. The table below summarizes common parameters and their functions.

Table 1: Common Selective Pressures in Top-Down Engineering

| Selective Pressure | Function in Community Steering |

|---|---|

| Substrate Type & Concentration [22] | Selects for species with specific metabolic pathways; high concentrations can functional streamlining. |

| Temperature [2] [21] | Influences growth rates and can be cycled to control population ratios. |

| pH [21] | Creates a niche favorable for acidophiles or alkaliphiles. |

| Cultivation Pattern (e.g., batch vs. continuous) [22] | Continuous culture can select for fast-growing species, while batch culture may allow more diversity. |

| Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) | In continuous systems, a short HRT washes out slow-growing organisms. |

FAQ 3: My enriched consortium is unstable over time. What could be wrong?

Instability, where a consortium's composition or function drifts over time, is a common challenge. The following troubleshooting guide addresses frequent causes and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Consortium Instability

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Dominance by a Single Species | Fast-growing organisms outcompete others for nutrients [21]. | - Adjust substrate gradient: Use a lower concentration of the preferred substrate [22].- Implement cyclic temperature changes: To physically control population dynamics [2]. |

| Loss of Keystone Populations | Slow-growing but critical species (e.g., syntrophic partners) are outcompeted [21]. | - Use serial transfer or continuous enrichment: This can help maintain minimal active consortia (MAMC) that have co-evolved for stability [2].- Consider spatial structuring: Use biofilms or membrane systems to protect niche populations [21]. |

| Functional Instability | The community lacks functional redundancy or is sensitive to minor perturbations. | - Apply directed evolution: Introduce controlled ecological disturbances (e.g., species invasion, nutrient shifts) to select for more robust communities [2]. |

FAQ 4: The function of my enriched consortium does not meet expectations. How can I improve its performance?

If your consortium's performance (e.g., degradation rate, product yield) is low, the issue may lie with the enrichment strategy or community composition.

- Verify the Selective Pressure: Ensure the applied pressure is strong and specific enough. For example, if degrading a recalcitrant pollutant, use it as the sole or primary carbon source.

- Analyze Community Structure: Use metagenomic sequencing to identify the dominant members and key functional genes [22] [23]. This can reveal if the wrong organisms are dominating or if essential degraders are missing.

- Check for Functional Compartmentalization: A highly effective consortium often displays a division of labor. Metagenomic analysis can reveal if this is present, as seen in a lignocellulose-degrading community where different members handled biomass deconstruction, fermentation, and methanogenesis [23].

- Re-assess the Inoculum Source: If performance remains low, try a different environmental inoculum that has a historical exposure to your target substrate or condition.

FAQ 5: Can I combine top-down and bottom-up approaches?

Yes, integrating both approaches is a powerful hybrid strategy, sometimes called "middle-out" [24]. A top-down enriched and simplified consortium can serve as a blueprint for a bottom-up design. For instance, metagenomic analysis of a top-down enriched consortium can identify the key members and their metabolic pathways. Researchers can then isolate these key players and re-assemble them into a defined synthetic consortium, offering greater control and predictability [2] [23]. This strategy leverages the functional efficiency of naturally selected communities while aiming for the controllability of synthetic systems.

Experimental Protocol: Top-Down Enrichment for a Hydrocarbon-Degrading Consortium

This protocol outlines a method for enriching a crude oil-degrading microbial consortium from contaminated soil, based on a published study [22].

Objective: To obtain a functionally streamlined microbial consortium capable of efficiently degrading crude oil.

Materials:

- Inoculum: Soil from a hydrocarbon-contaminated site.

- Basal Salt Medium (BSM): Provides essential nutrients (N, P, K, trace elements).

- Carbon Source: Crude oil (e.g., at 5 g/L as used in the study).

- Bioreactors: Serum bottles or flasks with airtight seals.

- Orbital Shaker: For incubation under aerobic conditions.

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Suspend 10 g of contaminated soil in 90 mL of sterile BSM. Shake vigorously and allow large particles to settle.

- Enrichment Culture: Transfer 10 mL of the soil suspension to a bioreactor containing 90 mL of BSM with crude oil as the sole carbon source.

- Incubation: Incubate the bioreactor aerobically (e.g., 150 rpm) at a suitable temperature (e.g., 30°C).

- Serial Transfer: Upon observing microbial growth (turbidity) and/or reduction in the oil layer, transfer a 10% (v/v) aliquot of the culture to a fresh BSM medium with the same concentration of crude oil.

- Repeat: Conduct multiple serial transfers (e.g., over several weeks) to progressively enrich for the most efficient oil-degrading microbes.

- Monitoring:

- Functional Performance: Track the crude oil degradation rate gravimetrically or via gas chromatography.

- Community Analysis: Periodically sample the consortium for DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing to monitor the simplification of the community structure and identify dominant taxa and key degradation genes [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Top-Down Enrichment Experiments

| Item | Function/Application in Top-Down Engineering |

|---|---|

| Basal Salt Media | Provides essential nutrients (N, P, K, trace metals) while allowing the target substrate (e.g., pollutant, waste biomass) to be the limiting factor. |

| Target Substrate (e.g., Crude Oil, Lignocellulose) | Serves as the primary selective pressure and carbon source to enrich for microorganisms with the desired catabolic ability [22]. |

| Continuous Bioreactor Systems | Allows for the control of parameters like Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT), which is a powerful selective pressure for enriching fast-growing, metabolically active populations. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (for Metagenomics) | Essential for extracting community DNA to track structural changes (e.g., via 16S rRNA sequencing) and functional potential (via shotgun metagenomics) during enrichment [22] [23]. |

| Inhibitor Compounds (e.g., antibiotics) | Can be used to selectively suppress the growth of specific microbial groups (e.g., bacteria to enrich for fungi) to understand functional roles. |

| IRAK4-IN-18 | IRAK4-IN-18, MF:C24H25FN6O3, MW:464.5 g/mol |

| Irak1-IN-1 | Irak1-IN-1, MF:C17H20N2O4, MW:316.35 g/mol |

Workflow for Achieving a Stable and Functional Consortium

The following diagram synthesizes troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols into a strategic workflow for developing a robust top-down enriched consortium, aligning with the thesis goal of improving stability.

Leveraging Narrow-Spectrum Resource-Utilizing Bacteria to Enhance Cooperation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) bacteria and why are they important for consortium stability?

NSR bacteria are strains with a specialized metabolic capability, allowing them to utilize a limited range of external resources. Their importance stems from their ability to reduce direct competition and enhance cooperative interactions within a community. Research shows that strains with a narrower resource utilization breadth significantly increase the metabolic interaction potential (MIP) and decrease metabolic resource overlap (MRO) in a community, which are key metrics for predicting stable coexistence. Integrated analyses confirm the central roles of NSR strains in forming metabolic interaction networks through the secretion of amino acids, vitamins, and precursors, thereby driving community stability and enhancing plant growth promotion [17] [25].

Q2: In a synthetic community, how can I quickly assess the resource utilization profile of my candidate strains?

You can efficiently determine the resource utilization width and overlap of your bacterial strains using high-throughput phenotype microarrays. These arrays test the ability of strains to metabolize a panel of carbon sources commonly found in your target habitat, such as the plant rhizosphere. The subsequent calculation of the average overlap index for each strain provides a quantitative measure of its potential to compete with others. For instance, in one study, the NSR strain Cellulosimicrobium cellulans E showed a resource utilization width of 13.10 and an overlap index of 0.51, in contrast to broad-spectrum utilizers like Bacillus megaterium L, which had a width of 36.76 and an overlap of 0.74 [17].

Q3: What are the primary experimental strategies for engineering stable cooperation in microbial consortia?

A primary strategy involves designing communities to foster mutualistic interactions and mitigate competition. Common approaches include:

- Programming Mutualism: Engineering strains to cross-feed essential metabolites, such as having one strain consume a growth-inhibiting byproduct (e.g., acetate) produced by another [26].

- Programmed Population Control: Using synchronized lysis circuits or other feedback mechanisms to prevent any single population from overgrowing and dominating the consortium [26].

- Utilizing Narrow-Spectrum Utilizers: Selecting strains with low metabolic resource overlap to naturally reduce competition and create niches for cooperation [17].

Q4: My synthetic community collapses over time, with one strain outcompeting the others. What are the likely causes and solutions?

Community collapse is often a result of unchecked competition or the absence of stabilizing interactions.

- Likely Cause 1: High Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO). If your strains have broadly similar resource utilization profiles, they will compete intensely for the same nutrients.

- Solution: Characterize the metabolic profiles of your strains and replace broad-spectrum utilizers with NSR strains to lower overall MRO [17].

- Likely Cause 2: Lack of Stabilizing Interactions. In the absence of mutualistic cross-feeding or population control, faster-growing strains will inevitably dominate.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Rectifying Community Instability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community collapse; one strain dominates. | High competition for resources (High MRO). | Perform phenotype microarray analysis on all strains to calculate resource utilization width and pairwise overlap [17]. | Replace broad-spectrum strains with narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) bacteria [17]. |

| Uncontrolled growth of a fast-growing strain. | Monitor individual population dynamics in the co-culture over time using selective plating or flow cytometry. | Engineer a programmed population control circuit (e.g., synchronized lysis) into the dominant strain [26]. | |

| Consortium shows low functional output (e.g., low metabolite production). | Inefficient metabolic exchange or burden. | Measure the concentration of key intermediates in the culture medium. | Re-distribute the metabolic pathway between strains to division of labor and reduce individual cellular burden [26]. |

| Lack of synergistic interactions. | Use genome-scale metabolic modeling (GMM) to simulate and calculate the Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) of your consortium [17]. | Re-design the community to include strains that provide central precursors or vitamins, as predicted by GMM [17]. | |

| Inconsistent performance across different experimental batches. | Fluctuations in initial population ratios. | Systematically vary the starting inoculum ratios and monitor final community composition. | Establish a standard pre-inoculation co-culture protocol to stabilize initial ratios. Use a calibrated frozen stock. |

| Unaccounted for environmental variables. | closely monitor and control factors like pH, temperature, and shaking speed. | Implement a chemostat or bioreactor system to maintain consistent environmental conditions throughout the experiment. |

Guide 2: Quantitative Metrics for Community Design

The following table summarizes key quantitative data from foundational research, providing benchmarks for designing your own stable consortia.

| Bacterial Strain | Resource Utilization Width (Carbon Sources) | Average Overlap Index | Key Plant-Beneficial Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulosimicrobium cellulans E | 13.10 | 0.51 | IAA Synthesis | [17] |

| Azospirillum brasilense K | 24.37 | N/P | Nitrogen Fixation | [17] |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri G | 25.59 | N/P | Nitrogen Fixation, Phosphate Solubilization, IAA Synthesis (66.08 mg·Lâ»Â¹) | [17] |

| Bacillus velezensis SQR9 | 35.50 | 0.83 | Phosphate Solubilization, IAA Synthesis, Siderophore Production | [17] |

| Bacillus megaterium L | 36.76 | 0.74 | Phosphate Solubilization, IAA Synthesis, Siderophore Production | [17] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens J | 37.32 | 0.72 | Phosphate Solubilization (46.39 mg·Lâ»Â¹), IAA Synthesis, Siderophore Production | [17] |

| Correlation with Stability | ↑ Width → ↓ Stability (R²=0.49 with MIP) | ↑ Overlap → ↓ Stability (R²=0.35 with MRO) | N/A | [17] |

N/P: Not explicitly provided in the source, but described as low. IAA: Indoleacetic acid.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Stable Synthetic Community Using Phenotype Microarray and Metabolic Modeling

This protocol provides a rational bottom-up strategy for constructing a stable synthetic microbial community.

I. Materials

- Candidate bacterial strains with desired functions (e.g., nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization).

- Biolog Phenotype Microarray PM1 or PM2 plates (or similar) containing 95 carbon sources.

- Sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl).

- IF-0a Inoculating Fluid (Biolog) or equivalent.

- Dye Mix A (Biolog) containing tetrazolium violet.

- Automated plate reader capable of reading at 590 nm.

- Software: BioLINX or similar for analyzing phenotype data; A genome-scale metabolic modeling (GMM) software suite (e.g., COBRA Toolbox).

II. Step-by-Step Method

- Strain Cultivation: Grow each candidate strain to the mid-exponential phase in an appropriate, low-nutrient broth.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash twice with sterile saline, and resuspend in inoculating fluid to a specified cell density (e.g., OD600 = 0.5).

- Phenotype Microarray Inoculation: Dispense 100 µL of each cell suspension into the wells of the Phenotype Microarray plate. Include control wells as per manufacturer's instructions.

- Incubation and Reading: Incubate the plates at your desired temperature (e.g., 28°C) and read the absorbance at 590 nm every 24 hours for 72-96 hours. The color change indicates metabolic activity.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Resource Utilization Width for each strain as the total number of carbon sources it can metabolize above a predetermined threshold.

- Calculate the Pairwise Overlap Index for all strain pairs as the number of shared carbon sources divided by the total number utilized by the pair.

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GMM):

- Construct or refine genome-scale metabolic models for each strain, using the phenotype microarray data to constrain and validate the models.

- Simulate all possible community combinations (from pairs to the full consortium) in silico.

- For each simulated community, calculate two key indices:

- Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP): A measure of cooperative potential.

- Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO): A measure of competitive pressure.

- Community Assembly: Select the community composition that the modeling predicts will have a high MIP and a low MRO. For example, a community (SynCom4) containing the NSR strains C. cellulans E and P. stutzeri G was shown to be highly stable and increased plant dry weight by over 80% [17].

Rational Community Design Workflow

Protocol 2: Engineering a Cross-Feeding Mutualism for Metabolic Pathway Division

This protocol outlines the steps to create a stable, two-strain consortium where each strain carries part of a metabolic pathway and they depend on each other for survival or function.

I. Materials

- Two engineered microbial strains (e.g., E. coli and S. cerevisiae or two E. coli auxotrophs).

- Strain A: Engineered to produce a key intermediate metabolite but lacking the ability to produce a final product or essential compound (e.g., an auxotroph for leucine).

- Strain B: Engineered to convert the intermediate into a valuable final product but lacking the ability to produce the intermediate itself (e.g., an auxotroph for lysine).

- Minimal media lacking the essential compounds that each strain is auxotrophic for.

- Appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance if using engineered plasmids.

- Shaking incubator and flasks for co-cultivation.

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, GC-MS) to quantify the final product and intermediate.

II. Step-by-Step Method

- Strain Design and Construction:

- Genetically engineer Strain A to overproduce and excrete Metabolite X (e.g., lysine). Also, delete a gene in its essential amino acid biosynthesis pathway (e.g., for leucine), making it a leucine auxotroph.

- Genetically engineer Strain B to efficiently uptake Metabolite X (lysine) and convert it into valuable Final Product Y. Delete a gene in its lysine biosynthesis pathway, making it a lysine auxotroph.

- Monoculture Validation:

- Confirm that Strain A cannot grow in minimal media without leucine but can grow if leucine is supplemented.

- Confirm that Strain B cannot grow in minimal media without lysine but can grow if lysine is supplemented.

- Co-culture Establishment:

- Inoculate both Strain A and Strain B together into minimal media that contains no supplemental leucine or lysine.

- The only way for both strains to grow is through mutualistic cross-feeding: Strain A provides lysine to Strain B, and Strain B provides leucine to Strain A. This design enforces cooperation and stable coexistence [26].

- Monitoring and Optimization:

- Monitor the co-culture over time by measuring optical density and using selective plating to track the population dynamics of each strain.

- Quantify the titer of Final Product Y and adjust parameters like inoculation ratio and media composition to optimize productivity and stability.

Engineered Cross-Feeding Mutualism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Microarray Plates (e.g., Biolog PM1/PM2) | High-throughput profiling of carbon source utilization to determine resource utilization width and overlap. | Essential for the initial screening and selection of NSR bacteria. Contains 95 different carbon sources [17]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GMM) | In silico simulation of metabolic networks to predict community-level interactions (MIP & MRO) before experimental assembly. | Constrained with phenotype microarray data for accuracy. Platforms like the COBRA Toolbox are commonly used [17]. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) System Parts | Genetic parts (e.g., lux, las, rhl systems) to engineer communication and synchronized behaviors between strains in a consortium. | Used for programming population control circuits or coordinating gene expression across different strains [26]. |

| Synchronized Lysis Circuit (SLC) Components | Genetic circuit elements to implement programmed population control, preventing overgrowth of any single strain. | Typically consists of a QS module linked to a lysis gene (e.g., E lysis protein), enabling density-dependent self-lysis [26]. |

| Bacterial Auxotrophs | Genetically engineered strains unable to synthesize an essential metabolite; used to create obligate mutualistic cross-feeding dependencies. | A powerful tool for enforcing stability. For example, a lysine auxotroph co-cultured with a leucine auxotroph in minimal media [26]. |

| Vegfr-2-IN-52 | Vegfr-2-IN-52, MF:C20H25ClN4O2S, MW:421.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IL-17-IN-3 | IL-17-IN-3, MF:C22H25F6N5O3S, MW:553.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary function of a quorum-sensing circuit in a synthetic microbial consortium? Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell-cell communication process where bacteria use the production and detection of extracellular chemicals called autoinducers to monitor cell population density [27]. In synthetic consortia, QS circuits synchronize gene expression across the population, allowing the group to act in unison and switch behaviors between low-cell-density (individual) and high-cell-density (social) programs [27]. This is crucial for implementing density-dependent functions, such as the coordinated production of a therapeutic compound or biofilm formation, within an engineered consortium [28] [29].

FAQ 2: Why is my consortium unstable, with one strain consistently outcompeting the others? This is a common challenge often stemming from unchecked growth competition and the lack of sufficient interdependency [28]. A single-metabolite cross-feeding interaction might not create a strong enough correlation to enforce stability [30]. To address this, consider implementing a multi-metabolite cross-feeding (MMCF) strategy that establishes essential, multi-point interactions between strains, for example, by coupling amino acid anabolism with energy metabolism like the TCA cycle [30]. Additionally, ensure that your QS circuit design includes proper feedback regulation to prevent one strain from dominating [28].

FAQ 3: How can I make my consortium's output self-regulating and responsive to intermediate metabolite levels? You can integrate metabolite-responsive biosensors (MRBs) with your quorum-sensing circuits [30]. For instance, a caffeate-responsive biosensor can be used to autonomously regulate population ratios in a consortium for coniferol production. When an intermediate metabolite accumulates, the biosensor triggers a genetic response to rebalance the consortium's activity, minimizing the accumulation of toxic or wasteful intermediates and maximizing the final product titer [30].

FAQ 4: I am not detecting the expected autoinducer activity. What could be wrong? This issue can be broken down into several potential failure points. First, verify the functional expression of your autoinducer synthase (e.g., a LuxI-type enzyme) and the correct synthesis of the acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signal [27]. Second, check the functionality and sensitivity of your receptor/transcription factor (e.g., a LuxR-type protein), as some require AHL binding for proper folding and stability [27]. Third, ensure the genetic parts (promoters, RBS) in your circuit are well-characterized and functioning as intended in your host chassis. A systematic troubleshooting guide is provided in the next section.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unstable Consortium Population

Observed Issue: The population composition of your synthetic consortium is highly sensitive to the initial inoculation ratios (IIRs) and drifts significantly over time, leading to inconsistent performance [30].

Recommended Solutions:

- Implement Multi-Metabolite Cross-Feeding (MMCF): Move beyond single-metabolite dependencies. Engineer strains that rely on each other for multiple essential metabolites (e.g., amino acids and TCA cycle intermediates) to create a stronger symbiotic correlation and intrinsic stability [30].

- Utilize Separate Carbon Sources: Reduce direct competition for food by engineering different consortium members to utilize distinct carbon sources (e.g., glucose and glycerol) [30].

- Dynamic Population Control: Incorporate a QS circuit linked to a growth-inhibiting gene (e.g., a toxin) or a essential metabolite cross-feeding pathway to create negative feedback that autonomously regulates population sizes [28].

Problem 2: Low or No Output from QS-Controlled Gene

Observed Issue: The target gene (e.g., for a therapeutic protein or a fluorescent reporter) under QS control is not being expressed, or expression levels are very low even at high cell density.

| Potential Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Autoinducer not produced/detected | Test for AHL presence using a reporter strain or HPLC-MS. Check for functional synthase and receptor expression [27]. | Use a high-copy plasmid for synthase/receptor expression; optimize codon usage; use a different AHL/receptor pair. |

| Insufficient cell density | Measure OD600 to confirm culture has reached high cell density. | Concentrate cells or allow more growth time. For very dilute cultures, consider using a different signal molecule or amplifying the QS circuit with a positive feedback loop [27]. |

| Signal crosstalk or degradation | Check for native QS systems in host chassis that could interfere. Look for enzymes (e.g., lactonases) that degrade AHLs [29]. | Use a non-native AHL/QS system; knock out native interfering systems; use a different host chassis. |

| Circuit tuning issues | Characterize promoter strength and RBS of all circuit components. | Re-tune the circuit by varying promoter strength, RBS, and plasmid copy number to achieve the required expression threshold. |

Problem 3: High Background Expression at Low Cell Density

Observed Issue: The QS-controlled gene is expressed even at low cell densities, leading to a leaky phenotype and loss of tight density-dependent control.

Recommended Solutions:

- Modify the Receptor/Promoter System: Use a LuxR-type receptor that is unstable without its AHL ligand (Class 1 or 2 receptors) [27]. For example, the TraR receptor degrades rapidly in the absence of its autoinducer, preventing background activation.

- Increase the Activation Threshold: Incorporate a repression mechanism. Use a promoter that is actively repressed at low cell density and only derepressed when the AHL-LuxR complex is present at a high concentration [27].

- Adjust AHL Diffusion: If using a hyper-diffusible AHL, consider engineering the system to use an AHL with a longer acyl chain, which may diffuse less readily [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Autoinducer Synthesis and System Responsiveness

This protocol is used to confirm that your engineered strain is producing a functional autoinducer and that the QS circuit responds appropriately.

Materials:

- Reporter strain (e.g., an AHL-sensitive strain containing a LuxR-type receptor and a GFP reporter plasmid).

- Test strain (your engineered strain).

- Appropriate liquid and solid media.

- Spectrofluorometer and spectrophotometer.

Method:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the test strain and a negative control strain (lacking the autoinducer synthase) to stationary phase.

- Conditioned Media: Centrifuge the cultures (e.g., 5,000 x g, 10 min) and filter-sterilize (0.22 µm filter) the supernatants to obtain "conditioned media" containing any secreted autoinducer.

- Reporter Assay: Dilute a fresh culture of the reporter strain 1:100 into fresh media and the conditioned media.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate the co-cultures with shaking. Periodically measure the optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (e.g., Ex/Em ~485/515 nm for GFP) over several hours.

- Analysis: Plot fluorescence/OD600 versus time or versus OD600. A significant increase in fluorescence in the test conditioned media, but not the control, indicates successful autoinducer production and circuit activation [27].

Protocol 2: Measuring Population Dynamics in a Two-Strain Consortium

This protocol provides a method to track the stability of a co-culture using fluorescent proteins and flow cytometry.

Materials:

- Two engineered strains, each with a different, stable fluorescent reporter (e.g., Strain A: pSA-eGFP; Strain B: pSA-mcherry) [30].

- Flow cytometer with appropriate lasers and filters.

- Selective media if required.

Method:

- Inoculation: Co-culture the two strains at different initial inoculation ratios (IIRs), for example, 80:20, 50:50, and 20:80 [30].

- Sampling: Take samples from the co-culture at regular time intervals (e.g., every 2-4 hours over 24-48 hours).

- Flow Cytometry: Dilute samples as needed and analyze them using a flow cytometer. Set gates to identify the population based on forward/side scatter and then measure green and red fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: For each time point, calculate the percentage of each strain in the total population. A stable consortium will show the population ratios converging to a narrow range regardless of the initial ratios [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| LuxI-type Synthase | Enzymatically produces the acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) autoinducer signal molecule [27]. | Specificity for AHL side-chain length (e.g., EsaI makes 3OC6HSL, LasI makes 3OC12HSL). Substrate availability (acyl-ACP, SAM) in host [27]. |

| LuxR-type Receptor | Binds the specific AHL autoinducer; the complex then acts as a transcriptional activator for target genes [27]. | Ligand specificity and folding class (Class 1/2 require AHL for stability). Can be used to create hybrid promoters (lux-type promoters) [27]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (eGFP, mCherry) | Enable visual tracking and quantification of population dynamics and gene expression in real-time using flow cytometry or microscopy [30]. | Ensure spectral separation and minimal metabolic burden. Use constitutive promoters for population tracking and inducible/QS promoters for circuit validation. |

| Metabolite-Responsive Biosensor | Detects the accumulation of a specific pathway intermediate and dynamically regulates gene expression in response [30]. | Key for self-regulation. Requires a characterized transcription factor and promoter responsive to the target metabolite (e.g., caffeate). Dynamic range and sensitivity are critical [30]. |

| E. coli BW25113 ΔpykA ΔpykF | A common chassis strain for metabolic engineering; deletion of pyruvate kinases directs carbon flux [30]. | Useful for creating metabolic interdependencies (e.g., in MMCF). Often requires further gene deletions (e.g., ppc, gdhA, gltBD) to create auxotrophies [30]. |

| GSK-114 | GSK-114, MF:C19H23N5O4S, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AST5902 mesylate | AST5902 mesylate, MF:C28H33F3N8O5S, MW:650.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram: Quorum-Sensing Activation Workflow

Diagram: Troubleshooting Unstable Consortium

Genetic Modification of Member Strains to Impose Obligate Mutualisms

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Why does my synthetically engineered mutualism consistently collapse, with one strain going extinct?

A: Consortium collapse is often due to the emergence of "cheater" mutants that benefit from the mutualism without contributing, ultimately destabilizing the system [31] [26]. In an obligate cross-feeding consortium of E. coli, over 80% of populations overcame a severe decline not by reinforcing the mutualism, but through evolutionary rescue where one strain metabolically bypassed the auxotrophy, effectively breaking the mutualism to survive [31].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Sequence Evolved Strains: After collapse, sequence the genome of the surviving strain to identify mutations that may have restored metabolic autonomy [31].

- Implement Population Control: Introduce synthetic genetic circuits to stabilize the population ratio. For example, use synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) where a quorum-sensing molecule triggers lysis once a population density threshold is crossed. This negative feedback prevents any single strain from overgrowing the other [26].

- Minimize Standalone Growth: Re-engineer your strains to delete more genes in the bypassed pathway, making a reversion to autonomy evolutionarily more difficult [31].

Q2: How can I reliably control the population composition of my consortium over the long term?

A: Precise population control requires engineering ecological interactions between your strains. Relying on co-culture in a shared medium without such controls often leads to instability [26].

Solution: Engineer programmed negative feedback loops.

- Method: Implement orthogonal synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) in each strain [26].

- Mechanism: Each strain is engineered to produce a unique quorum-sensing (QS) molecule. As the population density of a strain increases, it senses its own QS molecule. Upon reaching a critical threshold, it expresses a lethal protein, lysing a subset of its population.

- Outcome: This self-imposed population control creates a negative feedback loop, preventing any one strain from dominating and allowing for stable coexistence [26].

Q3: My mutualistic consortium shows high functional variability between experimental replicates. What could be the cause?

A: High variability can stem from uncontrolled initial conditions and a lack of robust, reciprocal cross-feeding [26].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Inoculation: Precisely control the starting optical density (OD) and ratio of each strain at inoculation.

- Verify Metabolic Dependence: Confirm that the metabolic exchanges you've engineered are truly obligate. In a well-designed mutualism, a study found that the average impact of gene disruptions was reduced, as the partner strain buffered the effects of minor defects, potentially leading to more reproducible community function [32].

- Spatial Structure: Consider growing your consortium in a spatially structured environment, like on agar surfaces, which can enhance the stability of cross-feeding interactions [32].

Q4: What are the most effective modern tools for creating the large genetic deletions needed for auxotrophy?

A: While CRISPR-Cas9 is widely used, CRISPR-associated transposon (CAST) systems are emerging as powerful tools for precise, large-scale genetic insertions or deletions without relying on the host's repair mechanisms [33].

Tool Comparison Table:

| Tool | Mechanism | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 with HDR | Creates double-strand breaks repaired using a donor DNA template via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [33] [34]. | Targeted gene knock-outs (deletions) and point mutations in strains with high recombination efficiency. | HDR efficiency can be low in non-dividing cells and some bacterial species [33]. |

| CRISPR-Cas12a | Cuts DNA and can process its own guide RNA arrays, allowing for multiplexed editing of several genes at once [35]. | Simultaneously disrupting multiple genes to create complex auxotrophies. | Requires a PAM sequence different from Cas9 for target recognition [35]. |