Harnessing Ecological Networks to Detect Influential Organisms: A Novel Framework for Sustainable Systems

This article explores the ecological-network-based approach for detecting organisms with disproportionate influence on system outcomes, a methodology with transformative potential for agriculture and drug discovery.

Harnessing Ecological Networks to Detect Influential Organisms: A Novel Framework for Sustainable Systems

Abstract

This article explores the ecological-network-based approach for detecting organisms with disproportionate influence on system outcomes, a methodology with transformative potential for agriculture and drug discovery. We detail the foundational theory of species interaction networks and keystone species, then present a cutting-edge methodological pipeline combining environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding and nonlinear time series analysis. The article addresses key challenges in data acquisition and network construction, provides a framework for experimental validation through manipulative experiments, and compares this approach to traditional methods. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this synthesis demonstrates how ecological network analysis can move beyond correlation to uncover causal biological drivers, enabling more targeted and sustainable interventions in complex biological systems.

The Power of Connections: Unraveling Ecological Networks and Keystone Species

Ecological networks provide a conceptual and quantitative framework for understanding the complex interactions that determine the distribution and abundance of organisms within ecosystems. These networks emerge from interactions within and between species and describe the interconnected nature of biodiversity [1]. Traditional ecology has heavily emphasized predator-prey interactions, forming food webs that map who-eats-whom in ecological communities [2]. However, contemporary ecological network science recognizes that species interact through multiple parallel pathways beyond consumption, including non-trophic interactions, ecosystem engineering, and mutualistic relationships [2].

The study of ecological networks has evolved from descriptive food web roadmaps to sophisticated analyses that incorporate the strength, direction, and nonlinear nature of species interactions. This progression enables researchers to address pressing conservation questions, including which species are most vulnerable to extinction, whether ecosystems with high biodiversity are under greater threat, and how the loss of key species cascades through ecosystems to impair functioning [2]. Understanding the processes that determine the strength and organization of interactions in food webs and other ecological networks is critical for anticipating how populations, communities, and ecosystems will respond to environmental change [1].

Key Concepts and Network Typology

Ecological networks can be categorized based on the types of interactions they represent. The table below outlines the principal network types and their characteristics.

Table 1: Types of Ecological Networks and Their Defining Characteristics

| Network Type | Primary Interaction | Key Metric | Ecological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Webs [1] [2] | Trophic (Consumer-Resource) | Trophic Position, Connectivity | Energy flow, nutrient cycling |

| Interaction Webs [2] | Non-Trophic (e.g., competition, pollination) | Interaction Strength | Population regulation, community stability |

| Stoichiometric Networks [2] | Resource Quality & Palatability | Elemental Ratios (C:N:P) | Decomposition rates, resource utilization |

| Parallel Networks [2] | Multiple Interaction Types | Cross-Linkage Intensity | Ecosystem multifunctionality |

Beyond these formal categories, ecologists recognize various indirect interactions that shape community dynamics:

- Exploitative competition: Occurs when two species negatively affect each other's abundance through feeding on a shared resource [1].

- Apparent competition: Occurs through shared natural enemies, where an increase in one prey species leads to an increase in predator abundance, which in turn suppresses a second prey species [1].

- Trophic cascades: Occur when the presence of a top predator suppresses the abundance or alters the behavior of an intermediate consumer, resulting in an increase in abundance of lower trophic levels [1].

Body size serves as a key organismal trait that influences food web interactions through its effects on an individual's metabolism and trophic position [1]. The strength of trophic cascades and other indirect interactions may be modified by changes in the abiotic environment, such as temperature and water availability [1].

Analytical Framework: An Ecological-Network-Based Approach

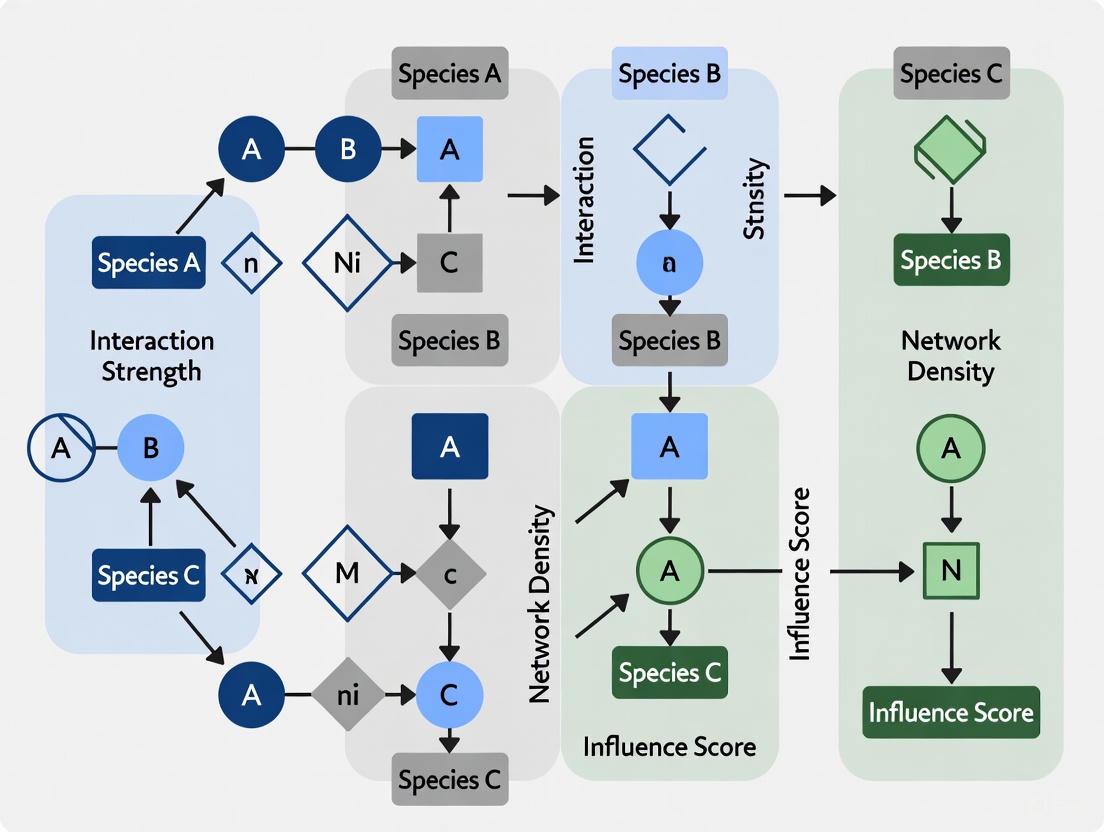

Advanced analytical methods now enable researchers to detect and quantify complex interactions within ecological networks. The following workflow illustrates the integrated protocol for detecting influential organisms using ecological network analysis.

Figure 1: Workflow for detecting influential organisms in ecological networks.

Phase 1: Intensive Field Monitoring and Data Collection

Protocol: Comprehensive Ecological Community Assessment

Objective: To monitor both the target species performance and the dynamics of the surrounding ecological community with high temporal resolution.

Materials and Equipment:

- Experimental plots or field sites

- Standardized measurement tools (e.g., rulers, calipers)

- Environmental DNA sampling kits (filter cartridges, preservatives)

- Water sampling equipment (if applicable)

- Climate monitoring sensors (temperature, light intensity, humidity)

- Sample storage and transportation systems

Procedure:

- Establish Experimental Plots: Set up replicated plots containing the target species. For example, in the rice study, researchers used small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm) filled with commercial soil and planted with rice seedlings [3] [4].

- Monitor Target Species Performance: Measure growth rates or other performance metrics daily. In the rice study, researchers measured rice leaf height of target individuals every day using a ruler, calculating daily growth rate in cm/day [3] [4].

- Collect Environmental DNA Samples: Gather samples frequently from the experimental plots. The rice study collected approximately 200 ml of water daily from each plot, which was filtered using Sterivex filter cartridges (φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm) [3] [4].

- Record Abiotic Variables: Monitor climate variables (temperature, light intensity, humidity) at each plot concurrently with biological sampling [4].

- Maintain Sampling Consistency: Continue daily monitoring throughout the study period. The referenced study maintained 122 consecutive days of monitoring, resulting in 1220 water samples across five plots [3] [4].

Phase 2: Molecular Analysis and Community Characterization

Protocol: Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

Objective: To comprehensively identify species present in the ecological community and quantify their relative abundances.

Materials and Equipment:

- DNA extraction and purification kits

- Universal primer sets for multiple taxonomic groups (e.g., 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI)

- High-throughput sequencing platform

- Internal spike-in DNA standards for quantification

- Bioinformatics software for sequence analysis

Procedure:

- Extract and Purify eDNA: Process filters from field sampling using standardized DNA extraction protocols [3].

- Quantitative Metabarcoding: Amplify target genetic regions using multiple universal primer sets. Include internal spike-in DNAs to enable quantitative assessment of abundances, as described in Ushio (2022) [3] [4].

- Sequence and Process: Perform high-throughput sequencing and process raw sequence data using appropriate bioinformatics pipelines.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign sequences to taxonomic units using reference databases. The rice study detected more than 1,000 species (including microbes and macrobes) in the experimental plots [3] [4].

- Create Abundance Tables: Generate quantitative abundance tables for all detected species across time points.

Phase 3: Time Series Analysis and Network Reconstruction

Protocol: Nonlinear Time Series Analysis for Interaction Detection

Objective: To identify causal relationships and potential interactions between species in the ecological community.

Materials and Equipment:

- Computational resources for time series analysis

- Statistical software (R, Python with appropriate packages)

- Nonlinear time series analytical tools

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile cleaned time series data for the target species performance metrics and all detected organisms.

- Causality Analysis: Apply nonlinear time series causality methods, such as convergent cross-mapping, to detect potential interactions [3]. These methods can identify causality even in complex, nonlinear systems [4].

- Identify Influential Organisms: Generate a list of species that show significant causal effects on the target species. In the rice study, this analysis identified 52 potentially influential organisms with lower-level taxonomic information [3] [4].

- Network Reconstruction: Reconstruct the interaction network surrounding the target species, representing the complex web of potential influences.

Phase 4: Experimental Validation

Protocol: Field Manipulation Experiments

Objective: To empirically validate the effects of candidate influential organisms identified through network analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Experimental plots or mesocosms

- Sources of candidate organisms (cultures, field collections)

- Organism removal equipment (if testing removal effects)

- Performance measurement tools

- Molecular analysis equipment for gene expression studies (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Select Candidate Organisms: Choose one or more species from the list generated through time series analysis for experimental testing. The rice study selected two species: the Oomycetes Globisporangium nunn and the midge Chironomus kiiensis [3] [4].

- Design Manipulation Experiments: Establish treatments that manipulate the abundance of candidate organisms:

- Addition treatments: Introduce candidate organisms to experimental plots

- Removal treatments: Remove candidate organisms from experimental plots

- Control treatments: Leave plots unmanipulated

- Implement Manipulations: Apply treatments to replicated plots. In the rice study, G. nunn was added and C. kiiensis was removed from artificial rice plots [3] [4].

- Measure Response Variables: Quantify the response of the target species before and after manipulation. Measure both phenotypic responses (e.g., growth rates) and molecular responses (e.g., gene expression patterns) if possible [3] [4].

- Statistical Analysis: Compare responses across treatments using appropriate statistical methods to confirm effects.

Case Study: Detecting Influential Organisms for Rice Growth

A proof-of-concept study demonstrates the application of this ecological-network-based approach for identifying previously overlooked organisms that influence rice growth in agricultural systems [3] [4]. The quantitative outcomes of this study are summarized below.

Table 2: Quantitative Results from Rice Ecological Network Study [3] [4]

| Parameter | Value | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring Duration | 122 days | Daily sampling from 23 May to 22 September 2017 |

| Experimental Plots | 5 | Small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm) with 16 Wagner pots each |

| Species Detected | >1,000 | Including microbes and macrobes (insects) via eDNA metabarcoding |

| Primer Sets Used | 4 | 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI regions targeting prokaryotes, eukaryotes, fungi, and animals |

| Influential Organisms Identified | 52 | Detected via nonlinear time series analysis |

| Organisms Validated | 2 | Globisporangium nunn (Oomycetes) and Chironomus kiiensis (midge) |

| Key Validation Result | Significant effect | G. nunn addition changed rice growth rate and gene expression patterns |

This study established that intensive monitoring of agricultural systems combined with nonlinear time series analysis could successfully identify influential organisms under field conditions [3] [4]. Although the effects of manipulations were relatively small, the research framework presents significant potential for harnessing ecological complexity to improve agricultural management.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Implementing ecological network analysis requires specific methodological tools and reagents. The following table outlines essential solutions for conducting such studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Ecological Network Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Application | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sterivex Filter Cartridges (φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm) [3] [4] | eDNA Sampling | Capture microbial and macrobial DNA from environmental samples |

| Universal Primer Sets (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI) [3] | DNA Metabarcoding | Amplify taxonomic-specific gene regions for community profiling |

| Internal Spike-in DNAs [3] [4] | Quantitative eDNA Analysis | Enable absolute quantification of species abundances in samples |

| DNA Extraction & Purification Kits | Molecular Analysis | Extract high-quality DNA from environmental filters |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Community Characterization | Generate sequence data for taxonomic identification |

| Climate Monitoring Sensors | Abiotic Data Collection | Record temperature, light intensity, and humidity concurrently with biological sampling |

| Hdac2-IN-2 | Hdac2-IN-2, MF:C18H15N3O3S, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Protoplumericin A | Protoplumericin A, MF:C36H42O19, MW:778.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The ecological-network-based approach outlined in this protocol moves beyond traditional food web studies to harness the full complexity of species interactions in ecosystems. By integrating intensive field monitoring, quantitative molecular methods, nonlinear time series analysis, and experimental validation, researchers can identify previously overlooked species that significantly influence target organisms. This methodology has particular relevance for sustainable agriculture, conservation biology, and ecosystem management, where understanding key interactions can inform interventions that enhance system productivity and resilience.

The case study on rice growth demonstrates that even in intensively studied agricultural systems, numerous unknown influential organisms may remain undetected without this comprehensive network approach. The detection of 52 potentially influential organisms, and subsequent validation of effects from two previously overlooked species, underscores the power of this methodology to reveal ecological drivers that operate through complex interaction networks.

The interplay between keystone species and ecosystem engineers represents a fundamental area of study in ecology, with profound implications for understanding community structure, ecosystem function, and conservation biology. Within the framework of ecological-network-based approaches for detecting influential organisms, these concepts provide the theoretical foundation for identifying species that exert disproportionate influence on their communities relative to their abundance or biomass [5].

Keystone species are defined as species, often of high trophic status, whose activities exert a disproportionate influence on the patterns of species occurrence, distribution, and density in a community [5]. The concept was originally founded on research surrounding the influence of a marine predator, the Pisaster ochraceus sea star, on intertidal communities [6]. Ecosystem engineers, in contrast, are defined as organisms that directly or indirectly modulate the availability of resources (other than themselves) to other species by causing physical state changes in biotic or abiotic materials [5] [7]. These organisms create or modify habitats, thereby influencing resource availability for other species [5].

The distinction between these concepts lies in their primary mechanisms of influence: keystone species typically exert their effects through trophic interactions (such as predation) or competition, while ecosystem engineers physically modify environments. However, both concepts share the fundamental characteristic of disproportionate ecological impact, making them central to network-based analyses of ecological communities [5] [7].

Theoretical Framework and Quantitative Definitions

Conceptual Distinctions and Operational Definitions

Within ecological network analysis, precise operational definitions are essential for identifying and quantifying the influence of keystone species and ecosystem engineers. The following table summarizes the key conceptual distinctions:

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison Between Keystone Species and Ecosystem Engineers

| Characteristic | Keystone Species | Ecosystem Engineers |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Trophic interactions, competition | Physical modification of habitat |

| Definition | Species with disproportionate effect on environment relative to biomass [5] | Organisms that create, modify, or maintain habitats [5] [7] |

| Trophic Level | Often high trophic status [5] | Any trophic level |

| Functional Redundancy | Low functional redundancy [6] | Varies depending on engineering capability |

| Impact Measurement | Effect on species diversity and distribution patterns [5] | Scale and magnitude of habitat modification [7] |

| Temporal Scale | Often immediate through trophic cascades | Can be long-lasting through structural changes |

Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Influence

The disproportionate influence of both keystone species and ecosystem engineers can be quantified using various network-based metrics. The following table outlines key quantitative parameters used in ecological network analyses:

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Ecological Influence in Networks

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Application to Keystone Species | Application to Ecosystem Engineers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Measures | Connectance, centrality measures, positional importance [5] [8] | Identifies species with high interaction strength | Maps modification of interaction pathways |

| Interaction Strength | Per-capita interaction strength, effect on community stability [5] | Quantifies disproportionate trophic effects | Measures engineering impact on resource availability |

| Diversity Impact | Species richness changes, β-diversity metrics [7] | Measures post-removal diversity loss | Quantifies diversity supported by engineered structures |

| Functional Measures | Trait-based metrics, functional diversity indices [7] | Assesses role in functional redundancy | Evaluates novel niche creation and habitat complexity |

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Validation

Ecological-Network-Based Detection Protocol

The following detailed protocol adapts methodologies from Ushio et al.'s research on detecting influential organisms for rice growth using ecological network approaches [3]:

Protocol Title: Nonlinear Time Series Analysis for Detecting Influential Organisms in Ecological Networks

Objective: To identify potentially influential species (including keystone species and ecosystem engineers) within complex ecological communities using frequent monitoring and causal inference techniques.

Materials and Reagents:

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling kits (filter apparatus, sterile containers)

- DNA extraction and purification kits

- Universal primer sets for multiple taxonomic groups (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI)

- Quantitative PCR reagents

- High-throughput sequencing platform access

- Spike-in DNA for quantitative metabarcoding [3]

Procedure:

Field Plot Establishment

- Establish replicate experimental plots (e.g., 5 plots as in Ushio et al. [3])

- Select appropriate scale for the ecosystem under study

- Ensure environmental homogeneity among plots where possible

Intensive Time-Series Monitoring

- Monitor target system performance metrics daily (e.g., plant growth rates)

- Collect environmental data concurrently (temperature, precipitation, etc.)

- Perform daily eDNA sampling from each plot [3]

- Maintain consistent sampling time and methodology throughout study period

Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

- Process water/soil samples using quantitative eDNA metabarcoding

- Employ multiple universal primer sets to cover diverse taxa

- Use spike-in DNAs to enable absolute quantification [3]

- Sequence amplified products using high-throughput platforms

Bioinformatic Processing

- Process raw sequence data using standard pipelines (quality filtering, clustering)

- Assign taxonomy using reference databases

- Generate quantitative abundance tables for all detected species

Nonlinear Time Series Analysis

- Apply empirical dynamic modeling techniques to detect causality

- Use convergent cross-mapping (CCM) or similar methods to identify directional influences

- Generate list of potentially influential organisms based on causal strength [3]

Network Construction and Analysis

- Construct interaction networks from causal inference results

- Calculate network metrics (centrality, connectivity) to identify key nodes

- Validate network stability and robustness

Expected Outcomes: A ranked list of potentially influential species with quantitative estimates of their impact on the system, specifically identifying keystone species and ecosystem engineers based on their network positions and interaction strengths.

Experimental Validation Protocol

Protocol Title: Field Manipulation Experiments for Validating Influential Organisms

Objective: To empirically test the effects of species identified as potentially influential through network analysis.

Materials:

- Experimental field plots or mesocosms

- Species-specific manipulation tools (additive or removal approaches)

- Measurement equipment for response variables

- Gene expression analysis equipment (if measuring transcriptomic responses) [3]

Procedure:

Candidate Species Selection

- Select top candidate species identified through network analysis

- Include both suspected keystone species and ecosystem engineers

Manipulation Design

- Employ additive approaches for suspected engineers (e.g., adding Globisporangium nunn)

- Use removal approaches for suspected keystone predators

- Include appropriate control treatments

- Replicate each treatment sufficiently [3]

Response Measurement

- Measure primary response variables (e.g., growth rates of dominant species)

- Quantify community-level responses (diversity metrics)

- Analyze molecular responses where appropriate (gene expression patterns) [3]

- Monitor environmental modifications for ecosystem engineers

Data Analysis

- Compare treatment effects against controls using appropriate statistical tests

- Evaluate magnitude and direction of effects

- Confirm hypothesized mechanisms of influence

Validation Criteria: Statistically significant changes in system performance metrics consistent with predictions from network analysis, demonstrating the causal influence of manipulated species.

Visualization of Methodological Workflows

Ecological Network Analysis Workflow

Mechanisms of Ecological Influence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Ecological Network Studies of Influential Organisms

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Monitoring Equipment | eDNA sampling kits, filter apparatus, sterile containers | Collection of environmental DNA for community analysis | Comprehensive species detection across taxa [3] |

| Molecular Analysis Tools | Universal primer sets (16S/18S rRNA, ITS, COI), DNA extraction kits, spike-in DNAs | Amplification and quantification of diverse taxonomic groups | Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding for absolute abundance [3] |

| Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput sequencers (Illumina, PacBio) | Generation of community composition data | Detection of 1000+ species from single experiments [3] |

| Computational Tools | Nonlinear time series packages, network analysis software | Detection of causal relationships and network construction | Empirical dynamic modeling, convergent cross-mapping [3] [8] |

| Manipulation Equipment | Species-specific addition/removal tools, mesocosms | Experimental validation of candidate species | Field tests of influential organisms [3] |

| Measurement Instruments | Growth rate monitors, environmental sensors, gene expression analyzers | Quantification of response variables | Measuring plant growth rates and transcriptional responses [3] |

| Hemiphroside B | Hemiphroside B, MF:C31H38O17, MW:682.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fortunolide A | Fortunolide A, MF:C19H20O4, MW:312.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Data Presentation and Case Studies

Documented Cases of Keystone Species and Ecosystem Engineers

Table 4: Empirical Examples of Keystone Species and Ecosystem Engineers

| Species/Group | Ecological Role | Mechanism of Influence | Documented Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pisaster ochraceus (sea star) | Keystone predator | Preys on dominant mussels | Removal reduced biodiversity by half; prevented competitive exclusion [6] | Paine (1966, 1969) |

| Gray wolves (Canis lupus) | Keystone predator | Trophic cascade through elk behavior | Reintroduction restored willow growth, beaver populations in Yellowstone [6] | Ripple & Beschta (2003) |

| African elephants (Loxodonta africana) | Keystone herbivore | Feed on trees and shrubs | Maintains savanna grassland; prevents woodland conversion [6] | Terborgh (1986) |

| European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | Ecosystem engineer | Warren construction | Increases lizard density and diversity [5] | Bravo et al. (2009) |

| Beavers (Castor canadensis) | Allogenic ecosystem engineer | Dam building and tree cutting | Converts streams to wetlands; increases species richness at landscape scale [5] [6] | Wright et al. (2002) |

| Earthworms (Lumbricus spp.) | Allogenic ecosystem engineer | Soil bioturbation and cast production | Alters soil structure, nutrient cycling, and microarthropod communities [5] [7] | Eisenhauer (2010) |

| Globisporangium nunn (Oomycete) | Potential ecosystem engineer | Identified through network analysis | Manipulation altered rice growth rates and gene expression [3] | Ushio et al. (2023) |

Quantitative Impacts of Species Removals and Additions

Table 5: Documented Quantitative Impacts of Manipulating Influential Species

| Study System | Manipulation | Response Variable | Magnitude of Effect | Time Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rocky intertidal (Tatoosh Island) | Sea star removal | Species diversity | Reduced from 15 to 8 species (47% decrease) [6] | 1 year |

| Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem | Wolf reintroduction | Willow height | Increased by 50-100% in some areas [6] | 5-10 years |

| Beaver addition | Beaver introduction | Aquatic species richness | Increased by 89% at landscape scale [5] | 3 years |

| Rice field system | Globisporangium nunn addition | Rice growth rate | Statistically significant changes observed [3] | Single growing season |

| European rabbit warrens | Warren availability | Lizard density | Significant increases in density and diversity [5] | Not specified |

Advanced Applications in Ecological Research

Integration with Emerging Technologies

The ecological-network-based approach for detecting keystone species and ecosystem engineers is increasingly enhanced by emerging technologies. Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding represents a particularly powerful tool, enabling researchers to monitor hundreds of species simultaneously and detect potentially influential organisms that might be overlooked by traditional methods [3]. This approach combines universal primer sets targeting multiple genetic markers (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI) with spike-in DNAs for absolute quantification, allowing comprehensive community monitoring across prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms [3].

The application of nonlinear time series analysis to these comprehensive datasets enables detection of causal relationships within complex ecological networks. Methods such as convergent cross-mapping can distinguish true causal interactions from simple correlation, providing a more robust foundation for identifying keystone species and ecosystem engineers [3]. This represents a significant advance over traditional observation-based approaches, which often struggled to quantify interaction strengths in diverse communities.

Conservation and Ecosystem Management Applications

Identification of keystone species and ecosystem engineers has direct applications in conservation biology and ecosystem management. The experimental validation protocol outlined in Section 3.2 provides a framework for empirically testing the effects of candidate species before implementing management interventions. This approach is particularly valuable in restoration ecology, where reintroduction of ecosystem engineers (such as beavers) or keystone species (such as wolves) can catalyze ecosystem recovery [5] [6].

Network-based approaches also enhance predictive capability in understanding ecosystem responses to anthropogenic disturbances, species invasions, and climate change. By identifying species with disproportionate ecological influence, conservation efforts can be prioritized toward protecting those organisms whose loss would trigger widespread community changes [5] [6]. The quantitative metrics outlined in Table 2 provide conservation planners with tools to assess the potential impact of species loss or addition in management scenarios.

The Critical Role of Indirect Effects and Trophic Cascades

Understanding trophic cascades—the indirect effects predators exert on non-adjacent trophic levels—is fundamental to predicting ecosystem responses to perturbation. Within an ecological-network-based approach, these cascades represent powerful pathways through which individual species can exert disproportionate influence across the entire system. The concept that "the truth is the whole" underscores that cascading effects cannot be understood by examining species in isolation, but must be viewed as emergent properties of the complete network of species interactions [9]. This document provides applied methodologies for researchers investigating these critical indirect effects, with particular emphasis on detecting influential organisms whose impacts ripple through ecological networks to effect change at multiple trophic levels, including biogeochemical processes such as carbon cycling [10].

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Trophic Cascades

Protocol 1: Long-Term Marine Coastal Monitoring

Application: Detecting cascades in kelp forest ecosystems involving whales, zooplankton, and urchins.

Method Summary: Researchers conducted an 8-year (2016-2023) study in Port Orford, Oregon, using a spatially explicit dataset integrating habitat, prey, and predator observations [11].

Detailed Workflow:

- Theodolite Tracking of Marine Mammals: A Sokkia DT210 theodolite positioned at a cliff-top location (elevation: 33 m) was used to non-invasively track gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) movements and quantify foraging time in two study sites (Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove) [11].

- Individual Whale Identification: Digital photographs were taken using a Canon EOS 70D camera to identify individual gray whales based on unique natural markings [11].

- Habitat and Prey Assessment: A tandem kayak was deployed to conduct daily assessments at 10 fixed target locations over rocky reef substrate. At each station, the following data were collected [11]:

- Kelp Condition: Assessment of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) frond and stipe condition.

- Urchin Coverage: Quantification of purple sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) coverage.

- Zooplankton Abundance: Measurement of zooplankton density (primarily mysid shrimp, ~85% of community) via plankton tows or other sampling methods.

Data Analysis: Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) were employed to (1) analyze temporal dynamics of all four species across the 8-year period, and (2) test for correlations along hypothesized trophic pathways (urchins → kelp → zooplankton → whales) [11].

Protocol 2: Terrestrial Carbon Flux Experiment

Application: Quantifying how predator-induced trophic cascades alter ecosystem carbon exchange.

Method Summary: A replicated field experiment using 13CO2 pulse-chase labeling to trace carbon fixation, allocation, and respiration in grassland enclosures with manipulated predator and herbivore presence [10].

Detailed Workflow:

- Enclosure Setup: Established replicated 0.25-m² fine-mesh enclosures in a grassland ecosystem with three experimental treatments [10]:

- Control: Plants only.

- + Herbivore: Plants and herbivores (grasshopper Melanoplus femurrubrum at natural field density).

- + Carnivore: Plants, herbivores, and carnivores (hunting spider Pisaurina mira at natural field density).

- Isotopic Labeling: At 21 days after stocking, each enclosure was pulse-labeled with

13CO2, and plant community uptake of the13C label was immediately measured [10]. - Respiratory Measurements: Total respiration of the

13C label was measured repeatedly throughout the remainder of the growing season to track carbon loss from the system [10]. - Carbon Allocation Analysis: At experiment termination, plant biomass was separated into aboveground and belowground components (and by species, e.g., grass vs. Solidago) to determine the allocation of the retained

13C [10]. - Animal Recovery: All added spiders and grasshoppers were recovered at the end of the experiment to confirm treatment integrity and assess potential consumptive effects [10].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Key quantitative findings from the cited research are synthesized in the tables below for comparative analysis.

Table 1: Summary of Trophic Cascade Effects on Ecosystem Structure and Function

| Study System | Trophic Levels Involved | Key Measured Variables | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Coastal [11] | Sea urchins → Kelp → Zooplankton → Gray whales | Urchin coverage, Kelp condition, Zooplankton abundance, Whale foraging time | Negative correlation between urchins and kelp; positive correlation between kelp and zooplankton; site-specific correlations between zooplankton/kelp and whale foraging. |

| Grassland Carbon Flux [10] | Spiders → Grasshoppers → Plants → Carbon Pool | 13C fixation, 13C respiration, 13C allocation (above/below ground) |

+Herbivore treatment reduced 13C fixation by 33%; +Carnivore treatment mitigated this decline. 1.4x more carbon retained in plant biomass with carnivores present. |

Table 2: Statistical Results from Trophic Cascade Studies

| Response Variable | Experimental Treatment/Correlation | Statistical Result | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

Plant 13C Fixation [10] |

+Herbivore vs. Control/+Carnivore | F~2,22~ = 7.15; P < 0.01 | Herbivory significantly reduced carbon fixation; predator presence mitigated this effect. |

Proportion of Fixed 13C Respired [10] |

+Herbivore vs. Control/+Carnivore | F~2,10~ = 4.73; P < 0.05 | A greater proportion of fixed carbon was lost via ecosystem respiration under herbivory. |

Total 13C Storage in Plant Biomass [10] |

Treatment effect | F~2,4~ = 10.26; P < 0.05 | The presence of carnivores significantly increased the retention of carbon in the ecosystem. |

Belowground 13C Allocation [10] |

Treatment effect | F~2,4~ = 18.68; P < 0.01 | Carnivore presence led to significantly greater belowground carbon storage. |

Visualizing Trophic Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows central to studying trophic cascades.

Trophic Cascade Network Pathways

Terrestrial Carbon Flux Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Trophic Cascade Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

Stable Isotopes (13COâ‚‚) |

To trace the pathway and fate of carbon as it moves through an ecosystem, quantifying fixation, respiration, and allocation. | Pulse-chase experiment to track carbon flow from plants to the ecosystem pool [10]. |

| Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) | A statistical modeling tool to analyze non-linear temporal dynamics and test for correlations along hypothesized trophic paths. | Modeling 8-year population trends and species correlations in the marine kelp system [11]. |

| Theodolite System | Precisely track and map the movement and behavior of large animals (e.g., marine mammals) from a fixed land-based position. | Quantifying gray whale foraging time and location in relation to prey and habitat availability [11]. |

| Field Enclosures | Manipulate species presence/absence and density in a controlled, replicated field setting to isolate causal relationships. | Creating defined plant-herbivore-carnivore treatments to test for trophic cascades [10]. |

| Digital SLR Camera | Identify individual animals based on natural markings for mark-recapture studies and behavioral monitoring. | Photographic identification of individual gray whales [11]. |

| Loop Analysis | A qualitative modeling technique to understand complex feedback relationships and identify operating pathways (e.g., TCs) within a whole food web context. | A critical review tool for analyzing the TC concept within the structure of entire ecological networks [9]. |

| Antioxidant agent-19 | Antioxidant agent-19, MF:C21H32O11, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Platycoside G1 | Platycoside G1, MF:C64H104O34, MW:1417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Linking Network Structure to Ecosystem Function and Service Provisioning

Application Notes

Theoretical and Practical Basis

The functional linkage between ecological network structure and ecosystem service provisioning is grounded in the concept that certain species, through their interactions, disproportionately influence ecosystem-level processes and stability. The approach integrates nonlinear time series analysis with high-resolution ecological community data to detect these influential organisms, moving beyond traditional pairwise interaction studies to a holistic, system-level understanding [3]. This methodology is particularly valuable for identifying potential biocontrol agents, ecosystem engineers, or other key organisms that can be harnessed for sustainable ecosystem management, such as increasing agricultural productivity with reduced environmental impact [3].

Key Quantitative Findings from foundational research

The application of this framework in an agricultural context (rice fields) yielded specific, quantifiable results demonstrating its utility. The table below summarizes the core findings from the initial monitoring and validation phases:

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings from Ecological Network Analysis in Rice Plots

| Research Phase | Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Monitoring (2017) | Monitoring Duration | 122 consecutive days [3] | Enables capture of complex, nonlinear dynamics. |

| Species Detected | >1,000 species (microbes and macrobes) [3] | Provides a comprehensive community profile. | |

| Potentially Influential Organisms Identified | 52 species [3] | Narrowes focus from thousands to dozens of key targets. | |

| Field Validation (2019) | Organism Manipulated (Globisporangium nunn) | Change in rice growth rate and gene expression [3] | Confirms causal influence of a detected organism. |

| Organism Manipulated (Chironomus kiiensis) | Change in rice growth rate and gene expression (effect smaller than G. nunn) [3] | Validates the method and shows species-specific effect strengths. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Intensive Field Monitoring and Sample Collection for Ecological Network Reconstruction

This protocol details the procedure for collecting the high-frequency, multi-taxa data required for subsequent nonlinear time series analysis [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Experimental Plots: Standardized field plots (e.g., for rice or other target organisms).

- eDNA Sampling Kit: Sterile water collection bottles, filters (e.g., 0.2µm pore size), and a filtration manifold.

- Preservation Solution: For storing eDNA filters (e.g., ATL buffer or ethanol).

- Spike-in DNAs: Known quantities of synthetic DNA sequences not found in natural environments, for quantitative metabarcoding [3].

- RNA Later Solution: For preserving plant tissue for transcriptome analysis.

- Environmental Data Loggers: To record abiotic factors (e.g., air and soil temperature, solar radiation).

II. Procedure

- Plot Establishment and Biological Monitoring: Establish replicate field plots. Daily, measure the growth rate (e.g., cm/day in height) of target plants from designated individuals [3].

- Environmental DNA Collection: Daily, collect water or soil samples from each plot. For water:

- Collect a standardized volume of water from each plot.

- Pass the water through a sterile filter to capture eDNA.

- Spike the sample with a known concentration of internal standard DNA prior to filtration for quantitative analysis [3].

- Preserve the filter at -20°C until DNA extraction.

- Plant Tissue Sampling for Transcriptomics: At regular intervals (e.g., weekly) or before/after key events, collect leaf tissue from target plants. Immediately place the tissue in RNA Later solution and store at -80°C to preserve RNA integrity [3].

- Abiotic Data Recording: Download continuous data from environmental loggers at regular intervals to correlate with biological time series.

Protocol 2: Nonlinear Time Series Analysis for Detecting Influential Organisms

This protocol describes the computational workflow to identify key species from the intensive monitoring data [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- High-Performance Computing Cluster: For handling large datasets and computationally intensive analyses.

- Bioinformatics Software: For processing raw DNA sequencing data (e.g., DADA2, QIIME2) to generate an Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) or Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) table.

- Statistical Software: R or Python with appropriate packages for time series analysis.

II. Procedure

- Quantitative Community Data Generation:

- Extract DNA from the collected eDNA filters.

- Perform PCR amplification using multiple universal primer sets (e.g., 16S rRNA for prokaryotes, 18S rRNA for eukaryotes, ITS for fungi, COI for animals) to cover a broad taxonomic range [3].

- Sequence the amplicons using high-throughput sequencing.

- Use the spike-in DNA counts to normalize sequence reads and convert them into absolute abundances, creating a quantitative time series for each detected species [3].

- Causality Analysis:

- Compile a master time series dataset containing the daily growth rate of the target plant and the absolute abundances of all detected species.

- Apply a nonlinear time series causality method, such as Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM), to the data [3].

- For each species, test if its past values can reliably predict the future state of the target plant (rice growth rate). A statistically significant result indicates a causal link [3].

- Generate a ranked list of species based on the strength of their causal influence on the target plant.

Protocol 3: Field Validation of Candidate Influential Organisms

This protocol outlines the manipulative field experiment to confirm the effects of candidate species identified in Protocol 2 [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Candidate Organisms: Cultures of the target species (e.g., Globisporangium nunn) or means for their removal (e.g., selective pesticides for Chironomus kiiensis).

- Experimental Plot Setup: New, replicated field plots for the manipulation experiment.

- Application Equipment: For adding cultures or removal agents to specific plots.

II. Procedure

- Plot Design: Establish a controlled experiment with the following treatments: a) Control, b) Candidate Species Added, and c) Candidate Species Removed (if applicable). Assign treatments randomly to plots [3].

- Manipulation:

- For additive treatment: Introduce a standardized quantity of the candidate organism (e.g., G. nunn zoospores) to the assigned plots at a phenologically relevant time [3].

- For removal treatment: Apply a selective removal method (e.g., larvicide for midges) to the assigned plots without significantly impacting non-target species.

- Response Measurement:

- Monitor plant growth rates in all plots before and after the manipulation.

- Collect plant tissue samples for transcriptome (RNA-seq) analysis before and after manipulation to assess changes in gene expression patterns [3].

- Data Analysis:

- Use statistical models (e.g., ANOVA) to compare the post-manipulation growth rates and gene expression profiles between treatment and control groups. A significant difference validates the organism's influential role [3].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Ecological Network Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Universal PCR Primer Sets | Amplification of taxonomic marker genes from eDNA for community profiling. | Targets include 16S rRNA (prokaryotes), 18S rRNA (eukaryotes), ITS (fungi), and COI (animals) [3]. |

| Internal Spike-in DNAs | Enables conversion of relative sequence reads to absolute species abundances in eDNA samples. | Synthetic DNA sequences added in known quantities prior to PCR; critical for quantitative time-series analysis [3]. |

| RNA Later Stabilization Solution | Preserves the integrity of RNA in plant tissue samples between field collection and lab processing. | Prevents degradation for reliable transcriptome (RNA-seq) analysis of plant physiological responses [3]. |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis Package | Statistical software to detect causal relationships from complex ecological time series data. | Methods like Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM) can identify causal links between species abundance and ecosystem function [3]. |

| Environmental DNA Sampling Kit | Standardized collection and filtration of water or soil samples for downstream DNA metabarcoding. | Includes sterile filters, bottles, and preservatives to minimize contamination and ensure sample consistency [3]. |

| Excisanin B | Excisanin B, MF:C22H32O6, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hebeirubescensin H | Hebeirubescensin H, MF:C20H28O7, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Historical Challenge of Quantifying Interactions in Complex Field Conditions

Understanding the web of interspecific interactions in natural field conditions has represented a significant historical challenge in ecology and agricultural science. Traditional observation- and manipulation-based approaches have faced critical limitations in identifying multitaxa species, quantifying their abundance under field conditions, and precisely measuring their complex, nonlinear interactions [3] [4]. This methodological gap has hindered our ability to harness ecological complexity for applications such as sustainable agriculture, where understanding how ecological community members influence crop performance could revolutionize management practices [3].

The emergence of advanced monitoring technologies and analytical frameworks now enables researchers to overcome these historical limitations. This protocol details an integrated approach combining quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis to detect and validate influential organisms within ecological networks, using a rice field system as a model [3] [4]. This methodology provides a framework for moving beyond simple correlation to infer causal relationships in complex field conditions.

Experimental Workflow and Methodological Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and analytical workflow for detecting and validating influential organisms in complex field conditions:

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for detecting and validating influential organisms in ecological networks through intensive monitoring, nonlinear time series analysis, and field validation.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential research reagents and materials for ecological network analysis in field conditions

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterivex Filter Cartridges [3] | eDNA collection from water samples | Two pore sizes: 0.22µm and 0.45µm; enables capture of diverse microbial and macrobial DNA |

| Universal Primer Sets [3] | DNA amplification for metabarcoding | Targets: 16S rRNA (prokaryotes), 18S rRNA (eukaryotes), ITS (fungi), COI (animals) |

| Internal Spike-in DNAs [3] [4] | Quantitative eDNA calibration | Enables absolute quantification of eDNA concentrations; critical for time-series analysis |

| Experimental Rice Plots [3] [4] | Controlled field environment | Small plastic containers (90×90×34.5cm); 16 Wagner pots with commercial soil; standardized conditions |

| Nonlinear Time Series Algorithms [3] | Causality detection in complex systems | Convergent Cross-Mapping (CCM) and related methods; detects causal relationships in nonlinear systems |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Phase 1: Intensive Field Monitoring Protocol

Objective: Establish comprehensive daily monitoring of rice performance and ecological community dynamics under field conditions.

Materials:

- Experimental rice plots (5 replicates recommended) [3]

- Sterivex filter cartridges (0.22µm and 0.45µm) [3]

- Universal primer sets for metabarcoding [3]

- Internal spike-in DNA standards [3] [4]

Procedure:

- Plot Establishment: Set up standardized rice plots using containers (90×90×34.5cm) filled with commercial soil and planted with rice seedlings (e.g., Hinohikari variety) [3].

- Growth Monitoring: Daily measurement of rice leaf height (largest leaf) using a ruler, recording growth rate in cm/day throughout the growing season (122 days recommended) [3].

- eDNA Sampling: Collect approximately 200ml of water daily from each plot. Filter immediately using dual Sterivex cartridges (0.22µm and 0.45µm) within 30 minutes of collection [3].

- Sample Processing: Extract eDNA from filters, incorporate internal spike-in DNAs for quantification, and perform metabarcoding with four universal primer sets [3].

- Climate Monitoring: Record complementary environmental variables (temperature, light intensity, humidity) at each plot [3].

Phase 2: Nonlinear Time Series Analysis Protocol

Objective: Identify potentially influential organisms through causal inference analysis of time series data.

Analytical Framework: The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for analyzing causal relationships in ecological networks:

Figure 2: Analytical framework for detecting causal relationships in ecological time series data using convergent cross-mapping.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile daily time series of rice growth rates and quantitative abundance data for all detected species (typically >1,000 species) [3].

- State-Space Reconstruction: Apply empirical dynamic modeling techniques to reconstruct the dynamic system from observed time series [3].

- Convergent Cross-Mapping: Test for causal relationships between each species and rice growth by assessing whether historical values of one variable can predict another [3].

- Significance Testing: Apply statistical thresholds to identify significant causal relationships (52 candidate species were identified in the reference study) [3].

- Candidate Selection: Prioritize organisms with strong causal signals for experimental validation.

Phase 3: Field Validation Protocol

Objective: Empirically validate the effects of candidate influential organisms through manipulative experiments.

Materials:

- Candidate organisms (e.g., Globisporangium nunn, Chironomus kiiensis) [3]

- Control and treatment rice plots

- Gene expression analysis equipment (RNA sequencing)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Establish replicated treatment and control plots following the same specifications as monitoring plots.

- Manipulation Implementation:

- Response Measurement:

- Statistical Analysis: Compare treatment and control responses using appropriate statistical tests.

Quantitative Results and Data Analysis

Table 2: Summary of quantitative results from ecological network analysis in rice field systems

| Parameter | 2017 Monitoring Results | 2019 Validation Results | Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring Duration | 122 consecutive days [3] | Growing season manipulation [3] | Daily sampling and measurement |

| Species Detected | 1,197 species total [3] | Focus on 2 candidate species [3] | Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding |

| Influential Organisms Identified | 52 potentially influential species [3] | Globisporangium nunn, Chironomus kiiensis [3] | Nonlinear time series analysis |

| Rice Growth Response | Daily growth rates measured [3] | Significant changes in growth rate [3] | Height measurement (cm/day) |

| Molecular Response | - | Gene expression pattern changes [3] | Transcriptome analysis |

| Statistical Validation | Causality detection via cross-mapping [3] | Field manipulation experiments [3] | Comparative analysis |

Discussion and Implementation Notes

The integrated framework presented here addresses the historical challenge of quantifying ecological interactions by leveraging frequent, comprehensive monitoring with advanced analytical techniques capable of detecting nonlinear causal relationships. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods that struggled with the complexity of field conditions [3].

Key advantages of this methodology include:

- Comprehensive species detection beyond traditional taxonomic limitations

- Causal inference rather than mere correlation

- Empirical validation of predicted interactions

- Application to sustainable agriculture through identification of previously overlooked influential organisms

The successful validation of Globisporangium nunn as an influential organism, despite its previously overlooked status, demonstrates the power of this approach to identify novel factors with potential relevance for crop growth and agricultural management [3]. This protocol provides researchers with a standardized framework for applying these methods across diverse ecological and agricultural systems.

A Practical Pipeline: From eDNA to Causal Inference with Nonlinear Time Series Analysis

Comprehensive Biodiversity Monitoring with Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

The intricate web of species interactions within an ecosystem plays a crucial role in determining its overall health and function. Understanding these complex networks is essential for detecting influential organisms that disproportionately impact community structure and ecosystem services. Traditional biodiversity monitoring methods often fail to capture the full scope of these interactions due to taxonomic limitations, effort requirements, and infrequent sampling. Quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding emerges as a transformative approach that enables frequent, comprehensive, and standardized monitoring of ecological communities by detecting trace genetic material shed by organisms into their environment [12]. When integrated with nonlinear time series analysis, this methodology provides a powerful framework for reconstructing interaction networks and identifying species with significant effects on key ecosystem functions or target species performance [3].

The application of this integrated approach in agricultural research demonstrates its considerable potential. A 2017 study on rice growth established small experimental plots and conducted daily monitoring of both rice growth rates and ecological communities using quantitative eDNA metabarcoding [3]. This intensive sampling regime, followed by the application of causal analysis to the time series data, successfully identified 52 potentially influential organisms from over 1,000 detected species [3]. Subsequent field validation in 2019 confirmed that manipulating the abundance of specific taxa, particularly the oomycete Globisporangium nunn, resulted in measurable changes in rice growth rates and gene expression patterns [3]. This research provides a validated framework for harnessing ecological complexity in managed ecosystems.

Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding Workflow

Core Principles and Definitions

Environmental DNA (eDNA) refers to genetic material obtained directly from environmental samples such as soil, water, or air without first isolating target organisms [12]. Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding extends this approach by incorporating internal standards (e.g., spike-in DNAs) during the laboratory processing phase, enabling researchers to not only detect species presence but also estimate their relative abundances in the sample [3]. This quantification is crucial for constructing accurate time series of population dynamics, which serves as the foundation for inferring ecological interactions. The method leverages high-throughput sequencing to simultaneously amplify and sequence DNA from multiple taxa using universal genetic markers, providing a holistic view of biological communities across the tree of life, from microbes to macrobes [3] [12].

Comparative Analysis of Monitoring Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of biodiversity monitoring approaches for detecting influential organisms.

| Feature | Traditional Morphological Surveys | Qualitative eDNA Metabarcoding | Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Scope | Typically limited to predefined taxa or size classes | Comprehensive across all life, but biased by primer choice [12] | Comprehensive across all life, with primer bias [3] [12] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Varies; can miss cryptic, small, or rare species | High sensitivity for rare and cryptic species [12] | High sensitivity for rare and cryptic species [3] |

| Abundance Data | Provides count-based data (e.g., individuals, cover) | Provides presence/absence or relative sequence abundance without internal standards | Provides quantitatively reliable relative abundance with internal standards [3] |

| Effort Required | High taxonomic expertise and time-intensive | Lower effort post-standardization, but computational bioinformatics effort needed | Lower field effort, but added complexity of quantitative calibration [13] [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Limited by cost and labor to infrequent sampling | Enables high-frequency, automated sampling (e.g., daily) [3] | Enables high-frequency, automated sampling (e.g., daily) [3] |

| Suitability for Network Analysis | Low, due to incomplete taxa and infrequent sampling | Moderate, but lack of reliable abundance data limits interaction inference | High, enables reliable inference of ecological interactions from abundance time series [3] |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Experimental Design and Sample Collection

- Site Selection: Establish replicated plots (e.g., 5 plots as in the rice study) that represent the ecosystem of interest [3].

- Sampling Frequency: Collect environmental samples (e.g., water, soil) at a high temporal frequency relevant to the system's dynamics. Daily sampling, as performed in the foundational study, is ideal for resolving biological interactions [3].

- Sample Type: The choice of matrix (water, soil, or air) depends on the ecosystem. For aquatic or semi-aquatic systems like rice paddies, water sampling is effective [3]. In terrestrial forests, soil and air sampling are more appropriate [12].

- Field Controls: Collect field negatives (e.g., sterile water exposed to the air during sampling) to monitor for cross-contamination.

Step 2: Sample Processing and DNA Extraction

- Filtration: Filter water samples through fine-pore membranes (e.g., 0.2-0.45 µm) to capture eDNA. Soil samples require a different initial processing step, often involving sieving and subsampling.

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial DNA extraction kits designed for complex environmental samples. The extraction should be efficient for a wide range of organisms, from microbes to animals.

- Quantitative Calibration: This is the critical step for quantification. Add a known quantity of synthetic internal standard DNA (e.g., unique DNA sequences from species not found in the study area) to each sample immediately post-filtration or at the start of DNA extraction [3]. This controls for variations in DNA extraction efficiency and PCR amplification bias.

Step 3: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- PCR Amplification: Amplify eDNA using multiple universal primer sets targeting different taxonomic groups. Standard markers include:

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries following standard protocols for the chosen sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq, HiSeq, or NovaSeq platform to achieve sufficient depth for community analysis.

Step 4: Bioinformatic Processing

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to samples based on unique barcodes.

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality sequences and trim adapters.

- Denoising: Use algorithms (e.g., DADA2, DEBLUR) to correct sequencing errors and infer exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs).

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, UNITE, BOLD) using BLAST or curated taxonomy assignment tools.

- Abundance Quantification: Calculate the relative abundance of each ASV by normalizing its read count against the read count of the spiked-in internal standard. This corrects for technical biases and provides quantitatively reliable data for time series analysis [3].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for quantitative eDNA metabarcoding, from experimental design to field validation.

Data Analysis for Detecting Influential Organisms

Time Series Causality Analysis

The processed quantitative data, which consists of a time series of relative abundances for hundreds of species, forms the basis for inferring ecological interactions. Nonlinear time series analysis methods, specifically convergent cross-mapping (CCM), are used to detect causal links between species [3]. CCM tests whether the historical record of one variable (e.g., the abundance of a putative influencer species) can reliably predict the state of another variable (e.g., rice growth rate or the abundance of another species). If it can, this provides evidence of a causal link. Applying this analysis pairwise across all detected species and the target performance metric (e.g., crop growth) allows for the reconstruction of a complex ecological interaction network and the identification of organisms that are potentially influential drivers within the system [3].

Field Validation Protocol

Identification through statistical analysis requires empirical validation. The following protocol outlines a field manipulation experiment based on validated methods [3]:

- Candidate Selection: From the list of statistically identified organisms, select candidates for validation based on the strength of their inferred effect and biological plausibility.

- Plot Establishment: Set up a new series of replicated field plots in the same ecosystem during a subsequent growing season.

- Treatment Application: Implement the following treatments in a randomized block design:

- Control: No manipulation.

- Addition: For a potentially beneficial organism (e.g., Globisporangium nunn), add a cultured strain to the plots at a concentration informed by the original time series data [3].

- Removal: For a potentially detrimental organism (e.g., Chironomus kiiensis), remove it using targeted methods like selective trapping or pesticides [3].

- Response Monitoring: Measure the response of the system.

- Performance Metric: Track the target metric (e.g., rice growth rate in cm/day) before and after manipulation [3].

- Molecular Response: For a deeper understanding, conduct transcriptomic analysis (RNA sequencing) on target organism tissues to identify changes in gene expression patterns in response to the manipulation [3].

- Statistical Comparison: Use analysis of variance (ANOVA) or similar models to compare the responses across treatment groups and confirm the causal effect.

Diagram 2: Logical flow of data analysis from time series data to the design of validation experiments.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for implementing quantitative eDNA metabarcoding.

| Category | Item | Function and Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Field Collection | Sterile Sample Containers / Filters | Collect environmental matrix (water, soil) without contamination. |

| Synthetic Spike-in DNA | Critical for quantification. Known sequences of non-native DNA added to each sample to calibrate extraction and amplification efficiency [3]. | |

| Personal Protective Equipment (Gloves) | Prevent contamination of samples with handler DNA. | |

| Lab Processing | DNA Extraction Kit | For complex environmental samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit). |

| Universal Primer Mixes | Target broad taxonomic groups (16S, 18S, ITS, COI) for PCR amplification [3]. | |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Reduces PCR amplification errors during library preparation. | |

| Size-Selection Beads | (e.g., AMPure XP) for cleaning and selecting appropriately sized DNA fragments post-amplification. | |

| Sequencing & Analysis | Sequencing Reagent Kit | (e.g., Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3). |

| Bioinformatic Software | (e.g., QIIME 2, DADA2, USEARCH) for processing raw sequence data into quantified ASV tables. | |

| Reference Databases | (e.g., SILVA, UNITE, BOLD) for taxonomic assignment of ASVs. | |

| Marsformoxide B | Marsformoxide B, MF:C32H50O3, MW:482.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Confiden | Confiden, MF:C12H14F3N5O6, MW:381.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Across Ecosystems

The quantitative eDNA metabarcoding framework is highly adaptable. While the foundational research was conducted in an agricultural context [3], the methodology is directly applicable to natural ecosystems for both basic and applied ecological research.

In forest ecosystems, eDNA metabarcoding is increasingly used to monitor the impacts of management and restoration. Studies have successfully tracked the recovery of diverse taxa—including plants, fungi, arthropods, and vertebrates—following restoration activities [12]. This application is particularly relevant for verifying biodiversity co-benefits in forest carbon projects, where there is a growing demand for standardized, auditable monitoring data [12]. The ability of eDNA to provide a permanent, verifiable record of species presence at a given site makes it an excellent tool for creating accountable data trails for conservation credit markets [12].

The taxonomic focus of eDNA studies (often on microbes, fungi, and invertebrates) complements the focus of many traditional conservation projects (which often target birds and mammals) [12]. Integrating eDNA into these projects can provide a more holistic understanding of the entire ecosystem network, revealing influential organisms at multiple trophic levels that would otherwise remain undetected.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the integration of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding into standard ecological monitoring faces several challenges. Methodological harmonization is needed to establish international common standards for sampling, laboratory protocols, and data processing to ensure data from different projects are comparable [13]. Bioinformatic bottlenecks include the need for comprehensive and curated reference databases to ensure accurate taxonomic assignment; gaps in these databases remain a significant limitation, especially for understudied regions and taxa [13] [12]. Data management requires robust infrastructure for storing and sharing the large volumes of sequence data generated, with strong support for the use of common European and national infrastructures to mandate standards and promote collaboration [13].

Future developments will focus on overcoming these hurdles through continued international collaboration, the development of user-friendly sampling kits, and clearer guidance for policymakers on interpreting eDNA-based results [13]. As the technology matures and becomes more integrated with automated sampling and AI-based data analysis, its potential to revolutionize how we monitor, understand, and manage complex ecological networks will be fully realized.

Ecological network analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for deciphering complex species interactions and identifying influential organisms within ecosystems. The reliability of these networks, however, is fundamentally dependent on the quality and structure of the underlying time series data. Flawed sampling strategies can introduce systematic biases that compromise network inference and lead to erroneous ecological conclusions. This Application Note provides a comprehensive framework for constructing robust ecological time series, integrating advanced sampling methodologies, statistical considerations, and practical protocols to overcome common pitfalls. Within the context of detecting influential organisms—a critical task for applications ranging from sustainable agriculture to ecosystem restoration—the strategic collection and processing of temporal data becomes paramount. We synthesize cutting-edge research to guide researchers in designing sampling regimes that accurately capture ecological dynamics while optimizing resource allocation.

The Critical Role of Sampling Design in Ecological Networks

The design of sampling protocols directly determines the analytical power and ecological validity of subsequent network reconstructions. Inadequate sampling can introduce two primary classes of errors: failure to detect true ecological interactions (Type II errors) and identification of spurious relationships (Type I errors). Research on microbial networks has demonstrated that temporal signals in species abundance data—including seasonal patterns, long-term trends, and autocorrelation—can generate co-occurrence patterns misinterpreted as biotic interactions. For instance, two unrelated species may appear associated simply because they both respond to seasonal environmental cues rather than through direct interaction [14].

The challenge of temporal autocorrelation is particularly pronounced in ecological time series. Unlike experimentally controlled laboratory systems, field-collected data exhibit inherent time-dependence where successive measurements are not statistically independent. This autocorrelation violates assumptions of many conventional statistical tests and can dramatically inflate false discovery rates if not properly addressed. Furthermore, the finite nature of time series creates systematic biases in biodiversity assessments. Neutral model simulations have revealed that even in the absence of environmental trends, temporal autocorrelation generates an expected increase in species richness over time due to the earlier detection of colonizations compared to extinctions. This baseline expectation must be considered when interpreting biodiversity trends from observational data [15].

Analyses of ecological networks operate at multiple hierarchical levels—pairwise interactions (flows), node-level properties, and whole-network characteristics—each providing complementary insights. However, conclusions drawn from one level do not necessarily align with those from another, emphasizing the need for sampling strategies that capture sufficient information for multi-level analysis [16]. The integration of these perspectives enables a more nuanced understanding of how individual species influence overall ecosystem structure and function.

Sampling Strategy Framework

Temporal Sampling Considerations

Table 1: Key Considerations for Temporal Sampling Design

| Factor | Recommendation | Rationale | Pitfalls if Ignored |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Frequency | Align with generation times of target organisms; typically weekly to monthly for microbial communities, daily during critical transition periods | Captures relevant ecological timescales without excessive autocorrelation | Missed rapid dynamics; oversampling wastes resources without information gain |

| Time Series Duration | Multiple cycles of dominant environmental fluctuations (e.g., 3+ years for seasonal systems) | Distinguishes directional change from cyclic variation | Inability to separate signal from noise; limited statistical power for trend detection |

| Temporal Resolution | Higher resolution during critical transition periods (e.g., bloom events, disturbance responses) | Captures nonlinear thresholds and rapid state changes | Missed critical transition events and causal relationships |

| Sample Size Estimation | Power analysis based on pilot data; >80% valid observations for highly variable parameters like precipitation | Ensures sufficient statistical power for detecting meaningful effects | High probability of Type II errors (missing true effects) |

The temporal design of sampling regimes must balance practical constraints with ecological reality. Research on climatic variables in forest ecosystems demonstrates that different environmental parameters have distinct sampling requirements. While monthly or seasonal statistics for air temperature can be reliably estimated with >50% missing values, precipitation requires >80% valid observations to accurately capture variability due to its inherently stochastic nature [17]. This parameter-specific requirement has profound implications for network inference, as incomplete representation of environmental drivers can obscure their influence on species interactions.

The timing and frequency of sampling should target both regular intervals and biologically significant events. Intensive daily monitoring of rice plots during growing seasons, combined with environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding, has successfully identified previously overlooked organisms influencing crop performance [18]. Such high-resolution data enables the application of nonlinear time series analysis to reconstruct interaction networks and detect causality—an approach that would be impossible with coarser sampling intervals.

Spatial Sampling Considerations

Spatial configuration of sampling points introduces another layer of complexity in time series construction. Spatial autocorrelation—the tendency for nearby locations to exhibit similar properties—can inflate effective sample size and lead to overconfidence in network predictions if not properly accounted for. Robust trend analysis in remote sensing applications addresses this through methods like the Contextual Mann-Kendall test, which explicitly incorporates spatial and cross-correlation structures [19].

For detecting influential organisms across heterogeneous landscapes, nested spatial designs often provide the most efficient approach. Broad-scale sampling establishes general patterns, while targeted intensive sampling at key locations captures fine-scale interactions. In arid region ecological networks, this approach has revealed critical threshold responses of vegetation to drought stress that would be obscured by purely random or uniform sampling designs [20].

Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated Field Sampling and eDNA Metabarcoding for Detecting Influential Organisms

Purpose: To comprehensively monitor ecological communities and identify species influencing focal organisms (e.g., rice growth) under field conditions.

Materials:

- Environmental DNA sampling kits (filters, preservatives)

- Quantitative PCR system

- High-throughput sequencing access

- Abiotic parameter sensors (temperature, humidity, light)

- Ruler or other growth measurement tools

- Sample storage at -20°C

Procedure:

- Plot Establishment: Set up replicated experimental plots containing the focal organism(s) in representative field conditions.

- Temporal Framework: Sample daily during critical growth periods or transition phases; weekly during stable periods.

- eDNA Collection:

- Collect water/soil samples from standardized locations within plots

- Filter immediately onto appropriate pore-size membranes

- Preserve filters in designated buffer solution