Harnessing Synthetic Microbial Consortia for Advanced Plastic Biodegradation: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

This article comprehensively examines the development and application of synthetic microbial consortia (SynComs) for plastic degradation, addressing a critical environmental challenge.

Harnessing Synthetic Microbial Consortia for Advanced Plastic Biodegradation: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the development and application of synthetic microbial consortia (SynComs) for plastic degradation, addressing a critical environmental challenge. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles of microbial ecology underpinning consortium design, methodological approaches for construction and optimization, troubleshooting of key limitations, and comparative validation against single-strain systems. The review highlights how division of labor in specialized microbial communities enables efficient degradation of complex polymers like PET, PE, and PP, while discussing emerging strategies in enzyme engineering, quorum sensing, and metabolic pathway optimization to enhance degradation efficiency and open new avenues for sustainable plastic waste management and biomedical applications.

The Science Behind Plastic-Degrading Microbial Consortia: From Natural Systems to Synthetic Ecology

Defining Synthetic Microbial Consortia (SynComs) and Their Advantages Over Single-Strain Approaches

Synthetic Microbial Consortia (SynComs) are artificially constructed communities composed of multiple, well-defined microbial species designed to perform specific, complex tasks through division of labor [1] [2]. The rational design of SynComs represents a significant advancement in synthetic biology, moving beyond the modification of single strains to embrace the ecological principles of natural microbial communities [3]. These consortia are engineered to exhibit controlled ecological interactions—such as mutualism, commensalism, competition, and predation—allowing them to achieve functionalities that are challenging or impossible for single-strain approaches [1] [2]. Within the specific context of plastic degradation research, SynComs offer a promising framework for tackling the persistent challenge of microplastic pollution by harnessing diverse enzymatic capabilities and synergistic interactions between microbial species [4] [5]. This application note delineates the core advantages of SynComs and provides detailed protocols for their application in polyethylene degradation research.

Comparative Analysis: SynComs vs. Single-Strain Approaches

The following table summarizes the key operational and performance differences between single-strain and consortium-based approaches.

Table 1: Advantages of Synthetic Microbial Consortia over Single-Strain Approaches

| Characteristic | Single-Strain Approach | Synthetic Microbial Consortia | Key Implications for Plastic Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | High burden from expressing complex pathways in one chassis [1]. | Division of labor distributes metabolic load across strains [1] [6]. | Enables expression of multiple, heavy enzymatic pathways (e.g., for different plastic polymers) [5]. |

| Functional Complexity | Limited to functions manageable by a single organism [2]. | Capable of executing complex, multi-step tasks [1] [2]. | Ideal for sequential degradation of polymers and their intermediate products [7] [5]. |

| System Stability & Adaptability | Prone to failure due to burden or environmental flux [2]. | Dynamic interactions provide resilience and adaptability [1]. | Consortia can maintain functionality under fluctuating environmental conditions [3]. |

| Pathway Efficiency | Risk of intermediate toxicity or metabolic bottlenecks [2]. | Complementary metabolic pathways can prevent accumulation of toxic intermediates [2]. | One strain can degrade inhibitory by-products generated by another, enhancing overall degradation rate [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a SynCom for Polyethylene (PE) Degradation

This protocol outlines a bottom-up approach for constructing a functional SynCom for PE degradation, from initial strain selection to performance validation.

Stage 1: Strain Selection and Characterization

Objective: To isolate and characterize microbial strains with putative PE-degrading capabilities and compatible growth conditions.

Materials:

- Source Material: Environmental samples from PE-contaminated sites (landfills, compost, marine debris) or agricultural waste composting systems [4] [5].

- Growth Media: Minimal salt media supplemented with specific carbon sources (e.g., lignin, oxidized PE, specific alkanes) to enrich for relevant microorganisms [5].

- Polymer Substrates: Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) or Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) films, either pristine or pre-treated (e.g., UV, heat) [4] [5].

Procedure:

- Enrichment Culture: Inoculate 1 g of source material into 100 mL of minimal media containing 200 mg of sterile PE film as the sole carbon source. Incubate with shaking (120 rpm) at 30°C for 4-8 weeks [5].

- Strain Isolation: Periodically subculture into fresh media. After several cycles, streak culture onto solid agar plates of the same media. Isolate distinct colonies.

- Functional Screening: Screen pure isolates for PE degradation traits:

- Strain Identification: Identify selected isolates using 16S rRNA (bacteria) or ITS (fungi) sequencing.

Stage 2: Consortium Design and Assembly

Objective: To rationally combine selected strains into a stable, cooperative consortium.

Materials:

- Genetically characterized pure cultures.

- Defined co-culture media.

Procedure:

- Define Ecological Interactions: Design desired interactions between strains. For PE degradation, a mutualistic system is often targeted. For example:

- Strain A: Specializes in initial biofilm formation and surface deterioration of PE, possibly producing biosurfactants [5].

- Strain B: Produces extracellular enzymes (e.g., peroxidases) to break down the long-chain polymers into shorter oligomers [5].

- Strain C: Utilizes the oligomers and fatty acids as a carbon source, preventing feedback inhibition and driving the degradation reaction forward [2] [5].

- Establish Communication (Optional): For precise control, engineer communication modules using orthogonal Quorum Sensing (QS) systems (e.g., LuxI/LuxR, LasI/LasR) to coordinate gene expression across the consortium [1] [6].

- Initial Assembly and Ratio Optimization: Inoculate strains in co-culture at varying initial ratios (e.g., 1:1:1, 10:1:1, 1:10:1). Monitor population dynamics over time using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with strain-specific primers or selective plating to identify a ratio that leads to stable coexistence [2].

Stage 3: Functional Validation and Analysis

Objective: To quantitatively assess the PE degradation capability of the assembled SynCom.

Materials:

- Assembled SynCom.

- Sterile PE films (pre-weighed).

- Analytical instruments: FTIR, GC-MS, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

Procedure:

- Degradation Assay: Inoculate the SynCom into serum bottles containing minimal media and a pre-weighed, sterile PE film (e.g., 50 mg). Include uninoculated controls and single-strain inoculated controls. Incubate for 60-90 days [7] [5].

- Physical and Chemical Analysis:

- Weight Loss: Periodically retrieve films, clean thoroughly, and measure weight loss [7].

- Surface Erosion: Analyze film surfaces using SEM for signs of cracking, pitting, and biofilm formation [5].

- Chemical Modification: Use FTIR to detect the formation of carbonyl groups, hydroxyl groups, or carbon double bonds, indicating polymer oxidation [5].

- Metabolite Analysis: Analyze the culture supernatant using GC-MS to identify intermediate degradation products (e.g., aldehydes, ketones, fatty acids) [5].

- Mineralization Assessment: Conduct the assay in a closed system and measure COâ‚‚ evolution as evidence of complete mineralization [5].

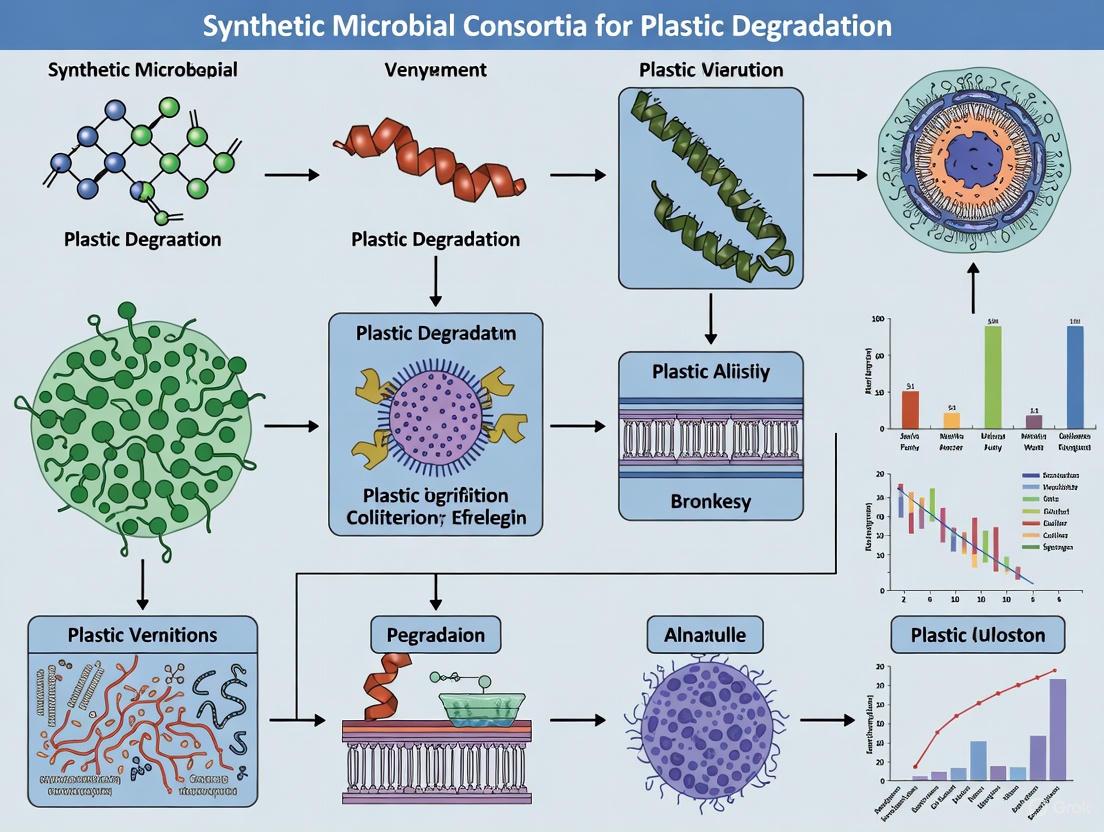

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SynCom Development in Plastic Degradation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Salt Media | A defined growth medium with essential salts, forcing microbes to utilize the target polymer as a carbon source. | Used throughout the protocol for enrichment, isolation, and degradation assays [5]. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Genetic parts (e.g., LuxI/LuxR, LasI/LasR) that enable density-dependent communication and coordinated behavior between strains [1] [6]. | Engineered in Stage 2 to synchronize enzyme production or biofilm formation across the consortium. |

| Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) | Small signaling molecules used in Gram-negative bacterial QS systems for intercellular communication [6]. | Added to media or produced by engineered strains to activate QS circuits in Stage 2. |

| Laccase & Peroxidase Substrates | Colorimetric or fluorogenic compounds (e.g., ABTS, guaiacol) used to detect and quantify relevant oxidative enzyme activity [5]. | Used in Stage 1, Step 3 to screen isolated strains for putative PE-degrading enzymes. |

| Polymer Substrates | Target plastics (ePE, LDPE, PET) in film or powder form, often pre-treated to introduce functional groups for microbial attack [4] [5]. | The central substrate of the degradation assay in Stage 3. |

| Selective Antibiotics | Antibiotics used as selective pressure to maintain plasmids or specific strain ratios in engineered consortia. | Can be used in Stage 2 to maintain stability in consortia containing antibiotic resistance markers. |

| DBCO-Sulfo-Link-Biotin | DBCO-Sulfo-Link-Biotin, MF:C31H35N5O7S2, MW:653.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Encenicline Hydrochloride | Encenicline Hydrochloride, CAS:550999-74-1, MF:C16H18Cl2N2OS, MW:357.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Conceptual Diagram of a PE Degradation SynCom

The diagram below illustrates the proposed division of labor and mutualistic interactions in a three-strain SynCom designed for enhanced polyethylene degradation.

The persistent accumulation of plastic waste, particularly poly-ethylene terephthalate (PET), represents a critical environmental challenge demanding innovative bioremediation strategies. This application note details the enzymatic machinery—PETases, MHETases, and Laccases—central to biological plastic degradation. Framed within the context of developing synthetic microbial consortia, this document provides researchers with a consolidated resource of quantitative enzyme performance data, standardized experimental protocols, and essential reagent solutions. The integration of these enzyme systems into cooperative microbial communities enables synergistic metabolic pathways, overcoming the inherent limitations of single-strain or single-enzyme approaches and paving the way for scalable plastic waste management solutions [8].

Key Enzymes in Polymer Degradation

- PETases: These hydrolases, often from the α/β-hydrolase superfamily, initiate PET depolymerization by cleaving ester bonds to produce mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (MHET) and other oligomers. Their unique strength lies in degrading PET at mesophilic temperatures, facilitated by a flexible active site and a canonical Serine-Histidine-Aspartate catalytic triad [9].

- MHETases: Acting downstream of PETases, MHETases specifically hydrolyze the soluble intermediate MHET into the PET monomers terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG). This completes the depolymerization process, making monomers available for microbial assimilation [10] [11].

- Laccases: These multicopper oxidases attack a different spectrum of polymers, including polyurethane and lignin-derived compounds. They operate through a radical-based oxidation mechanism, making them particularly useful for degrading additives and complex polymers often found in mixed plastic waste [12] [8].

Comparative Enzyme Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize key biochemical properties and performance metrics of engineered enzyme variants to aid in selection and application.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PET-Degrading Enzymes

| Enzyme | Source / Variant | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Melting Temp (Tm, °C) | Key Mutations (if any) | Catalytic Efficiency Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PETase | Ideonella sakaiensis (WT) | 30 - 40 | ~48.1 [13] | - | High depolymerization at room temperature [9] |

| FAST-PETase | Engineered variant of IsPETase | N/R | 63.3 [13] | S121E, D186H, R280A, R224Q, N233K [13] | Rapid depolymerization of post-consumer PET; rate enhancement via electrostatics and stability [13] |

| LCC | Leaf-branch compost cutinase | >65 [9] | 85.8 (LCC), 93.3 (LCCICCG) [14] | - | High thermostability; optimal activity near PET glass transition temperature [14] [9] |

| MHETase | Ideonella sakaiensis (WT) | N/R | N/R | - | Poor recombinant expression, a key limitation [10] |

| MHETase | Consensus-designed variant | N/R | N/R | Multiple consensus mutations | >10-fold increase in whole-cell activity due to improved soluble expression and folding [10] |

| Laccase | Fungal / Bacterial sources | 15 - 40 (depends on variant) | N/R | - | Immobilization crucial for stability and reusability; used for micropollutant degradation [12] |

Table 2: Experimental Hydrolysis Performance Data

| Enzyme / System | Substrate | Experimental Conditions | Key Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAST-PETase [13] | Untreated post-consumer PET | Mild, aqueous conditions | Complete depolymerization; superior rate and substrate versatility |

| LCCICCG-S165A [14] | PET polymer | NMR analysis at 50°C vs 30°C | Twofold reduction in global tumbling time (τc); significant S/N improvement in spectra |

| NusA-IsPETaseMut [15] | PET | Fusion system | 1.4x higher PET adsorption constant; reduced TPA product inhibition |

| Cross-linked Laccase [12] | Diclofenac (micropollutant) | Immobilized on cellulose acetate membrane | 58% removal efficiency achieved |

| Microbial Consortia [8] | PE, PET, PS | Cooperative metabolism in mixed cultures | Superior degradation via complementary enzyme production and synergistic effects |

The degradation pathway for PET involves sequential and synergistic actions of these enzymes, as illustrated below.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experimental procedures relevant to the study and application of plastic-degrading enzymes, from structural analysis to whole-cell activity assays.

Protocol 1: High-Temperature NMR for Rapid Backbone Assignment of Thermostable PETases

This protocol leverages high-temperature NMR to accelerate the spectral assignment of thermostable PETases like LCCICCG, facilitating rapid structural insights [14].

- Primary Application: Determining the backbone resonance assignment of thermostable PET-degrading enzymes.

- Principle: Recording triple-resonance NMR spectra at high temperatures (e.g., 50-60°C) reduces the global tumbling time (τc) of the enzyme, leading to improved Signal-to-Noise (S/N) ratios and faster data acquisition, making the assignment process comparable in speed to crystallography [14].

- Materials:

- Purified, isotope-labeled (15N, 13C) PETase (e.g., LCCICCG-S165A variant, ~580-600 µM).

- NMR buffer (e.g., 25 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5).

- High-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 800 MHz, 900 MHz) equipped with a cryoprobe.

- Sealed NMR tube to prevent sample evaporation.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate the purified, labeled protein in NMR buffer. For the active LCCICCG variant, a sample of 600 µM in the specified buffer is used [14].

- Temperature Calibration: Precisely calibrate the NMR spectrometer's temperature control system for the target temperatures (e.g., 50°C and 60°C).

- Data Acquisition: a. Acquire a 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum as a reference. b. Record a set of 3D triple-resonance experiments. Standard spectra like HNCACB and HNCO are acquired at 50°C. For more challenging assignments, pulse sequences like hNcaNNH and HncaNNH can be feasibly acquired at 60°C without deuteration [14]. c. Utilize Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS) to reduce acquisition time for these 3D experiments [14].

- Data Processing and Analysis: Process acquired data using software like TopSpin or similar. Analyze spectra and perform backbone assignment manually using software such as CcpNmr Analysis or POKY [14].

- Notes: The entire process, from data acquisition to analysis, can be completed in approximately two weeks, enabling NMR to contribute at a competitive pace in protein engineering projects [14].

Protocol 2: Whole-Cell Activity Assay for MHETase Variants

This protocol describes a medium-throughput assay to screen MHETase variants for enhanced soluble expression and activity directly in whole cells [10].

- Primary Application: Quantifying the hydrolytic activity of MHETase variants in cell lysates and whole-cell suspensions.

- Principle: The assay measures the conversion of the substrate MHET into its products (TPA and EG). Increased whole-cell activity is a direct indicator of improved soluble expression and folding of the enzyme within the host cell [10].

- Materials:

- Library of E. coli cells expressing engineered MHETase variants (e.g., generated via consensus design).

- Substrate: Mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (MHET).

- Assay buffer (e.g., phosphate or Tris buffer at optimal pH for MHETase).

- Microplates and plate reader for medium-throughput analysis.

- Cell lysis reagents (e.g., lysozyme, sonication equipment) for lysate preparation.

- Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Grow and induce expression of MHETase variants in a 96-deep well plate format.

- Sample Preparation: a. Whole-Cell Suspension: Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash, and resuspend in assay buffer to a standardized optical density. b. Cell Lysate: Lyse a portion of the cells using chemical or mechanical methods. Clarify by centrifugation to obtain soluble lysate.

- Reaction Setup: In a microplate, mix the substrate (MHET) with either the whole-cell suspension or the cell lysate.

- Activity Measurement: Incubate the plate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 30°C). Monitor the reaction spectrophotometrically or fluorometrically by tracking the release of TPA, or use HPLC/MS to quantify product formation over time.

- Data Analysis: Calculate reaction rates. Compare the whole-cell and lysate activities of variants against the wild-type MHETase. A significant increase in whole-cell activity indicates improved soluble expression and folding [10].

- Notes: This assay was pivotal in identifying consensus-designed MHETase variants exhibiting over a 10-fold increase in whole-cell activity compared to the wild-type enzyme [10].

Protocol 3: Immobilization of Laccase in Cellulose Acetate Membranes

This protocol outlines a two-step process for immobilizing laccase as Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) within a biodegradable cellulose acetate microfiltration membrane, creating a catalytic membrane for micropollutant remediation [12].

- Primary Application: Creating a stable, reusable, and easily separable biocatalytic membrane for continuous-flow degradation of micropollutants like diclofenac.

- Principle: Laccase is first adsorbed onto the high-surface-area porous structure of the cellulose acetate membrane. Subsequent cross-linking with glutaraldehyde stabilizes the enzyme aggregates within the pores, preventing leaching and enhancing operational stability [12].

- Materials:

- Cellulose acetate microfiltration membrane.

- Laccase enzyme solution.

- Glutaraldehyde solution (cross-linker).

- Adsorption buffers (e.g., acidic buffers around pH 4).

- Shaking incubator.

- Procedure:

- Adsorption Optimization: a. Incubate the cellulose acetate membrane with the laccase solution. Key parameters to optimize are pH (acidic, ~pH 4), temperature (29°C), enzyme concentration, and adsorption time [12]. b. After adsorption, wash the membrane gently to remove unbound enzyme.

- Cross-Linking: a. Immerse the laccase-loaded membrane in a glutaraldehyde solution of optimized concentration. b. Incubate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 4°C to minimize enzyme denaturation during cross-linking) for a defined period. c. Thoroughly wash the membrane with buffer to remove any residual cross-linker.

- Activity Assay: Determine the immobilization efficiency and surface activity of the catalytic membrane by measuring the oxidation of a model substrate (e.g., ABTS) [12].

- Notes: Under optimized conditions, this method achieved an immobilization efficiency of 76% and a high surface activity of 1174 U·mâ»Â². The resulting membrane was successfully used for the degradation of diclofenac, achieving a 58% removal efficiency [12].

The workflow for immobilizing laccase and constructing a catalytic membrane is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Proteins (15N, 13C) | Enables detailed structural and dynamic studies via NMR spectroscopy. | Essential for backbone assignment protocols (e.g., LCCICCG-S165A variant) [14]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Systems (GroEL/ES) | Co-expression to improve soluble yield of recombinant enzymes in E. coli. | Increased soluble yield of IsPETaseMut by 12.5-fold [15]. |

| Fusion Tag Systems (NusA) | Enhances solubility and expression of difficult-to-express proteins. | Yielded 4.6-fold more soluble NusA-IsPETaseMut; also modulated adsorption and inhibition properties [15]. |

| Cross-Linking Reagents (Glutaraldehyde) | Stabilizes immobilized enzymes by forming covalent cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs). | Used to cross-link laccase within cellulose acetate membranes, boosting operational stability [12]. |

| Biodegradable Carrier Membranes (Cellulose Acetate) | Serves as a sustainable solid support for enzyme immobilization in bioreactors. | Used for laccase immobilization; avoids microplastic pollution from synthetic polymer membranes [12]. |

| Model Plastic Substrates | Standardized substrates for reproducible enzyme activity assays. | PET films/dimer for PETase/MHETase [13] [9] [11]; ABTS for laccase activity [12]. |

| Glycerophosphoinositol choline | Glycerophosphoinositol choline, CAS:425642-32-6, MF:C14H32NO12P, MW:437.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hexaethylene glycol phosphoramidite | Hexaethylene glycol phosphoramidite, MF:C42H61N2O10P, MW:784.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

The integration of detailed enzyme kinetics, robust structural analysis protocols, and advanced enzyme engineering and immobilization techniques provides a powerful toolkit for advancing plastic biodegradation research. The data and methods outlined here—ranging from the rapid characterization of thermostable PETases to the creation of highly active whole-cell biocatalysts and immobilized enzyme membranes—are fundamental building blocks. When these tools are applied within the conceptual framework of synthetic microbial consortia, they enable the rational design of complex communities where specialized enzymes like PETases, MHETases, and Laccases work in concert through division of labor and cross-feeding interactions [8]. This synergistic approach, mimicking natural 'plastispheres', promises to overcome the limitations of individual enzymes and unlock more efficient and scalable bioremediation solutions for plastic waste.

Application Notes: Microbial Plastic Degradation Capabilities

The escalating crisis of global plastic pollution necessitates the development of innovative bioremediation strategies. Synthetic microbial consortia, which leverage the synergistic activities of diverse microorganisms, present a promising solution for enhancing the biodegradation of recalcitrant synthetic polymers. This document details the functional capabilities and experimental protocols for four key microbial groups—Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, and Actinobacteria—showcasing their proven roles in degrading conventional and bio-based plastics. The data provided serves as a foundational resource for constructing and optimizing synthetic consortia for plastic waste management.

Table 1: Quantitative Plastic Degradation by Key Microbial Strains

| Microbial Strain | Plastic Polymer | Degradation Efficiency / Key Metrics | Experimental Conditions & Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC6051 [16] | Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) | 3.49% weight loss | Bushnell-Haas broth, 37°C, 30 days |

| Bacillus licheniformis ATCC14580 [16] | Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) | 2.83% weight loss | Bushnell-Haas broth, 37°C, 30 days |

| Bacillus subtilis GM_03 [17] | Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) & Polyurethane (PU) | Degraded multiple plastic types; 6-fold increase in PU degradation rate after directed evolution | M9 minimal salts agar with LDPE or Impranil (commercial PU) |

| Streptomyces gougerotti [18] | Polystyrene (PS) | 0.67% weight loss; Formation of clear zone halo on emulsified PS | Addition of yeast extract to culture medium |

| Nocardiopsis prasina [18] | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | 1.27% weight loss | UV pre-treated PLA films, yeast extract added, 37°C |

| Micromonospora matsumotoense [18] | LDPE, PS | Degraded conventional plastics and produced PHA bioplastics | Use of UV pre-treated thin plastic films |

| Fusarium oxysporum [19] | Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Preferential growth on edges/corners; penetration into material through fractures; surface cracks | 90-day incubation on PET fragments |

| Fusarium, Penicillium, Botryotinia, Trichoderma strains [20] | Polyethylene, Polyurethane, Tyre Rubber | High degradation potential for multiple polymers; no pre-treatment required | Assays in liquid media and on agar |

The degradation process involves both physical and biochemical mechanisms. Fungi like Fusarium oxysporum exhibit strong infiltrative abilities, penetrating plastic substrates and creating micro-fractures that increase the surface area for enzymatic attack [19]. Biochemically, microbes produce extracellular enzymes (e.g., esterases, cutinases, lipases) that break down the polymer chains into smaller oligomers and monomers, which are then assimilated as carbon and energy sources [19] [18] [21]. For instance, the degradation of PET by F. oxysporum is facilitated by cutinases that hydrolyze ester bonds, similar to their action on natural plant polyesters [19].

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines standardized methodologies for evaluating the plastic degradation potential of microbial strains, from initial screening to advanced visualization.

Protocol 1: Screening for Plastic Degradation Potential using Emulsified Media

This method is effective for the rapid, high-throughput screening of microbial isolates, particularly actinomycetes [18].

Preparation of Plastics Emulsified Media:

- Solubilize the target plastic polymer (e.g., PS, PLA) in an appropriate organic solvent at elevated temperature (~80°C for 20 minutes).

- Add a dispersing agent like Tween-20 (0.05% v/v) to the solution to create a homogeneous emulsion.

- Mix this emulsion with a sterile, molten minimal agar medium (e.g., Carbon-Free Minimal Medium - CFMM) and 5x M9 minimal salts.

- Pour the mixture into Petri dishes to solidify.

Screening Procedure:

- Inoculate candidate microbial strains onto the surface of the emulsified media plates.

- Incubate at the optimal temperature for the strain (e.g., 28-30°C for fungi, 37°C for many bacteria) for up to two weeks.

- Observe the formation of a clear "halo" zone around the microbial colonies, which indicates hydrolysis of the emulsified polymer.

Analysis:

- Measure the diameter of the clearance halo as a preliminary indicator of degradation capability.

Protocol 2: Biodegradation Assay using Thin Plastic Films

This protocol provides quantitative and qualitative data on degradation through weight loss, chemical changes, and mechanical property assessment [18] [16].

Film and Inoculum Preparation:

- Cut the polymer of interest (e.g., LDPE, PS, PLA) into standardized, pre-weathered films (e.g., 3x3 cm). Sterilize by soaking in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes and air-drying.

- Prepare a microbial cell suspension in a minimal salt medium (e.g., Bushnell-Haas Broth) without carbon sources. Wash cells to remove residual nutrients.

Incubation:

- Place the sterile plastic film into a flask containing the minimal broth.

- Inoculate with the prepared microbial suspension.

- Incubate with constant shaking (e.g., 135 rpm) at the strain's optimal temperature for a defined period (e.g., 30 days). Include uninoculated controls.

Post-Incubation Analysis:

- Weight Loss: Retrieve films, clean rigorously with SDS (2%), ethanol (70%), and distilled water to remove microbial biomass. Dry and weigh. Calculate percentage weight loss [16].

- Surface Analysis: Examine film surfaces using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for physical alterations like cracks, pits, and biofilm formation [19] [16].

- Chemical Analysis: Use Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) to detect oxidative changes (e.g., formation of carbonyl groups at ~1740 cmâ»Â¹) and changes in polymer composition [18] [16].

- Mechanical Testing: Assess changes in tensile strength and Young's Modulus to determine the loss of structural integrity [18].

Protocol 3: Correlative Microscopy for Fungal-Plastic Interaction Analysis

This advanced workflow allows for a comprehensive, multi-scale investigation of fungal colonization and degradation, as demonstrated for Fusarium oxysporum on PET [19].

Workflow Description:

- Initial X-ray Microscopy (XRM): Non-destructively image the entire plastic fragment colonized by the fungus at low resolution to identify key colonization sites (edges, corners, planar surfaces) [19].

- Scout & Zoom: Select specific Volumes of Interest (VOIs) for high-resolution XRM. Apply a Deep Learning reconstruction algorithm (e.g., DeepScout) to enhance image quality, reducing noise and artifacts [19].

- Correlative SEM and Spectroscopy: Guide further analysis using the XRM data.

- Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for high-resolution visualization of surface morphology, hyphal penetration, and crack formation [19].

- Use Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) for elemental analysis of the surface.

- Use Raman spectroscopy to detect changes in the chemical structure and composition of the polymer [19].

- Data Integration: Correlate all multimodal data (3D morphology from XRM, surface topology from SEM, elemental data from EDX, and chemical data from Raman) to build a comprehensive model of the fungal-plastic interaction [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Plastic Biodegradation Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bushnell-Haas (BH) Broth [16] | A defined minimal salts medium used to assess biodegradation with the plastic as the sole carbon source. | Used in thin film assays with Bacillus species to degrade LDPE [16]. |

| M9 Minimal Salts [18] [17] | A common minimal medium for bacteria, often supplemented with emulsified plastics for screening. | Formulated with emulsified LDPE or PS to isolate and screen plastic-degrading actinomycetes and Bacillus [18] [17]. |

| LDPE, PS, PLA, PU Films | Standardized polymer substrates for degradation assays. | Sourced as thin, pre-weathered films (e.g., 3x3 cm) for quantitative weight loss and FTIR analysis [18] [16]. |

| Polymer Emulsifiers (e.g., Tween 20) | To create stable, homogeneous emulsions of plastic powders in aqueous culture media for initial screening. | Used in the preparation of plastics emulsified media for halo-based screening assays [18]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Detects formation of new functional groups (e.g., carbonyl index at ~1740 cmâ»Â¹) indicating polymer oxidation. | Standard method to confirm oxidative degradation across all microbial groups [18] [16]. |

| X-ray Microscopy (XRM) | Non-destructive 3D visualization of microbial colonization and penetration inside plastic fragments. | Key technique in correlative workflow to study Fusarium oxysporum inside PET [19]. |

| Specific Microbial Strains | B. subtilis ATCC6051, S. gougerotti, F. oxysporum Schltdl. | Well-documented strains with proven degradation activity, serving as positive controls or consortium components [19] [18] [16]. |

| Hydroxy-Amino-bis(PEG2-propargyl) | Hydroxy-Amino-bis(PEG2-propargyl), CAS:2100306-77-0, MF:C16H27NO5, MW:313.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyltetrazine-PEG4-Maleimide | Methyltetrazine-PEG4-Maleimide, MF:C24H30N6O7, MW:514.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Synthetic polymer pollution represents a formidable environmental challenge due to the inherent durability and chemical complexity of widely used plastics such as polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). The structural robustness of these polymers, while beneficial for applications, confers significant recalcitrance to biological degradation, complicating bioremediation efforts. Within this context, synthetic microbial consortia offer a promising framework for enhancing plastic biodegradation by leveraging synergistic metabolic capabilities across multiple microbial species. This application note details the specific substrate challenges posed by PE, PET, PP, and PVC and provides established protocols for developing and evaluating microbial consortia capable of their degradation, supporting advanced research in environmental biotechnology and waste management.

Polymer Characteristics and Degradation Challenges

The degradation susceptibility of plastic polymers is intrinsically linked to their chemical structure, molecular weight, crystallinity, and additive content. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and degradation challenges for PE, PET, PP, and PVC.

Table 1: Characteristics and Degradation Challenges of Key Polymer Substrates

| Polymer | Chemical Structure | Key Characteristics | Degradation Challenges | Susceptible Degradation Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | Long-chain alkane backbone with minimal branching [22]. | High molecular weight, hydrophobicity, semi-crystalline, no functional groups [23]. | Lacks enzymatically attackable functional groups; high hydrophobicity impedes microbial adhesion [23]. | Initial abiotic oxidation (e.g., UV) creates carbonyl groups for subsequent microbial attack [24]. |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Aromatic terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol monomers linked by ester bonds [22]. | High transparency, good mechanical strength, low gas permeability [22]. | Aromatic rings provide stability; ester bonds shielded by hydrophobic and crystalline regions [25]. | Hydrolysis of ester bonds by specific enzymes (e.g., cutinases, PETases) [25]. |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Linear hydrocarbon chain with a methyl group substituent on every other carbon [22]. | Lighter than PE, higher heat resistance, sensitive to UV radiation [22]. | Tertiary carbon atoms are susceptible to UV-initiated oxidation, but solid polymer resists microbial breakdown [22]. | Photo-oxidation creates carbonyl and hydroxyl groups, facilitating bio-utilization. |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Chlorine atoms attached to every other carbon in the backbone [22]. | Good chemical resistance, mechanical strength; often contains plasticizers [22]. | C-Cl bond is highly stable; often contains toxic additives (e.g., phthalates) that can inhibit microbes [22]. | (Bio)abiotic dechlorination is a critical first step; microbial degradation often targets plasticizers first. |

The degradation process for these polymers often begins with abiotic factors such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation, heat, and mechanical stress, which introduce functional groups (like carbonyls) and reduce polymer chain length. This initial weathering is a critical precursor for efficient microbial colonization and enzymatic attack [23]. Among the polymers, the high crystallinity of PET and the exceptional chemical stability of C–C (in PE, PP) and C–Cl (in PVC) bonds present the most significant barriers to rapid biodegradation.

Protocol: Development of a Plastic-Degrading Microbial Consortium via Induced Enrichment

This protocol describes a method for selecting a microbial consortium from an environmental inoculum using a target plastic as the sole carbon source, inducing selective pressure for degraders [23].

Materials and Reagents

- Soil Sample: Collected from a plastic-contaminated site (e.g., landfill, agricultural soil).

- Target Polymer: Pure polymer of interest (PE, PET, PP, or PVC) in film or powder format (<0.5 mm).

- Minimal Saline Medium (MSM): A carbon-free basal salts medium [23].

- Containers: Erlenmeyer flasks (250 mL) or serum bottles.

- Equipment: Laminar flow hood, incubator, centrifuge, ultra-centrifugal mill (for powder preparation).

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential enrichment protocol for developing a plastic-degrading microbial consortium.

Procedure

- Microcosm Establishment: Bury sterile pieces of the target plastic (e.g., LLDPE film) in soil. Incubate for 3 months in the dark at 30°C, maintaining 40-50% humidity to enrich for native plastic-degrading microbes [23].

- Sequential Enrichment: a. Inoculate 5 g of the pre-enriched soil into 50 mL of MSM in a 250 mL flask. b. Add the target plastic (1% w/v powder or multiple film pieces) as the sole carbon source [23]. c. Incubate at 30°C with shaking for 30 days. d. Transfer 5 mL of this culture to fresh MSM with new plastic pieces/powder. e. Repeat this transfer 3-4 times to select for a stable, plastic-adapted consortium [23].

- Consortium Characterization: Monitor microbial abundance and diversity across transfers via plate counts and molecular techniques (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing). A successful selection is indicated by a stabilization of the community composition and a reduction in diversity, highlighting the enriched, specialist degraders [23].

Protocol: Evaluating Consortium Degradation Efficiency

This protocol outlines methods to quantify and characterize the degradation of plastics by a microbial consortium.

Materials and Reagents

- Established Microbial Consortium

- Sterile Polymer Films: Pre-weighed and sized films.

- Analytical Equipment: Analytical balance, FTIR spectrometer, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

Procedure

- Weight Loss Measurement: The most direct metric for degradation [24].

a. Prepare pre-weighed sterile polymer films.

b. Inoculate films in MSM with the active consortium. Include uninoculated controls.

c. After incubation (e.g., 45 days), carefully remove films, clean with detergent to remove biofilm, and dry thoroughly.

d. Measure the final weight. Calculate percentage weight loss:

[(Wi - Wf) / Wi] × 100, where Wi and Wf are the initial and final weights, respectively. Studies with insect-gut symbionts have reported LDPE weight losses of 11.6% to 19.8% over 45 days [24]. - Surface Change Analysis: a. Use Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to detect the formation of new functional groups (e.g., carbonyl index, hydroxyl groups) on the polymer surface, indicating oxidative degradation [24]. b. Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize surface colonization, biofilm formation, and the appearance of cracks, erosion, or cavities.

- Polymer Property Analysis: a. Perform Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to monitor reductions in the polymer's average molecular weight, indicating chain scission [24]. b. Conduct Tensile Strength tests to measure the loss of mechanical integrity [24].

- Metabolite Identification: Use Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify low-molecular-weight degradation products (e.g., alkanes, alcohols, carboxylic acids) in the culture medium, confirming microbial utilization of the polymer [24].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Assessing Polymer Degradation

| Analysis Method | Parameter Measured | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Weight Loss | Reduction in sample mass | Direct evidence of material removal and mineralization. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Formation of carbonyl (-C=O), hydroxyl (-OH) groups | Evidence of polymer oxidation, a key first step in degradation. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Decrease in molecular weight (Mw, Mn) | Confirmation of polymer chain scission (depolymerization). |

| Tensile Strength Testing | Reduction in mechanical strength | Indicates breakdown of polymer matrix integrity. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Identification of small molecules (alkanes, acids, etc.) | Reveals intermediate metabolites and degradation pathways. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface erosion, cracks, biofilm coverage | Visual confirmation of physical degradation and colonization. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents for conducting plastic biodegradation studies with microbial consortia.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Plastic Degradation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Saline Medium (MSM) | Provides essential inorganic nutrients without organic carbon, forcing microbes to utilize the plastic [23]. | Selective enrichment and degradation experiments. |

| Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) Powder | A standardized, high-surface-area substrate for enrichment cultures and high-throughput screening [23]. | Selecting consortia with enhanced degradation kinetics. |

| Lignin-Modifying Enzyme Assay Kits | Quantify activity of laccase (Lac), manganese peroxidase (MnP), lignin peroxidase (LiP) [24]. | Correlating consortium activity with known recalcitrant-polymer-degrading enzymes. |

| Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide (HPAM) | Model compound for studying microbial degradation of acrylamide-based polymers in contaminated environments [26]. | Investigating consortia for bioremediation of polymer-flooding residues in oil recovery. |

| Insect Gut Microbiota Isolates | Source of novel, potent plastic-degrading strains (e.g., Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [24]. | Inoculum for constructing synthetic consortia. |

| m-PEG9-phosphonic acid | m-PEG9-phosphonic acid, MF:C19H41O12P, MW:492.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-(Azido-PEG2)-N-Fluorescein-PEG4-acid | N-(Azido-PEG2)-N-Fluorescein-PEG4-acid, CAS:2086689-06-5, MF:C38H45N5O13S, MW:811.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The complexity of synthetic polymers like PE, PET, PP, and PVC demands sophisticated biological solutions. The protocols and analyses detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to develop and characterize synthetic microbial consortia. By understanding the specific challenges of each polymer substrate and applying rigorous enrichment and evaluation methods, the scientific community can advance the field of plastic bioremediation, contributing to the development of sustainable and scalable environmental technologies.

Ecological Principles Governing Microbial Interactions in Consortia

Microbial consortia are complex communities where multiple microbial species coexist and interact within a shared environment. The study of these consortia is fundamentally guided by ecological principles that dictate how microorganisms assemble, compete, cooperate, and ultimately function as a collective entity. In natural environments, microbes rarely exist in isolation; instead, they form sophisticated communities with intricate interaction networks that enhance their survival capabilities and metabolic efficiency. The ecological interactions within these microbial ecosystems are essential for understanding critical community properties such as stability, resilience, and functional output [27] [3].

The application of these ecological principles to design synthetic microbial consortia represents a frontier in biotechnology, particularly for addressing complex challenges like plastic degradation. Synthetic consortia are artificially constructed communities where two or more microorganisms are co-cultivated under controlled conditions to perform specific functions [28]. Unlike single-strain approaches, these consortia leverage natural ecological relationships, such as division of labor and cross-feeding, to achieve more efficient and robust bioprocessing capabilities. By understanding and engineering these fundamental ecological interactions, researchers can develop more effective solutions for environmental remediation, including the breakdown of recalcitrant plastic polymers [27] [29].

Key Ecological Interactions in Microbial Consortia

Types of Ecological Interactions

Microbial interactions within consortia can be broadly categorized based on their effects on the participating organisms, ranging from beneficial to antagonistic relationships. These interactions form the foundation of community dynamics and ultimately determine the consortium's overall function and stability [27].

Table 1: Classification of Ecological Interactions in Microbial Consortia

| Interaction Type | Effect on Species A | Effect on Species B | Description | Example in Plastic Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Beneficial | Beneficial | Both species derive benefit from the interaction, often through metabolite exchange | Pseudomonas strains specializing on different PET monomers (TPA and EG) both benefit from complete plastic degradation [29] |

| Commensalism | Beneficial | Neutral | One species benefits while the other is unaffected | One species degrades plastic additives, making the polymer more accessible to other species without affecting the degrader [30] |

| Competition | Harmful | Harmful | Both species compete for limited resources (space, nutrients) | Multiple bacterial strains competing for access to the plastic surface as a carbon source [27] |

| Amensalism | Harmful | Neutral | One species inhibits another without being affected | Production of antimicrobial compounds that inhibit non-degrading microbes without cost to the producer [3] |

| Predation | Beneficial | Harmful | One species consumes another | Bacteriovorous protists consuming bacterial degraders in a consortium [3] |

These ecological interactions are not static but are often context-dependent, shaped by environmental factors such as nutrient availability, temperature, pH, and the presence of other community members [3]. The net effect of these interactions determines the consortium's functional stability and metabolic efficiency, both critical considerations when designing consortia for specific applications like plastic degradation.

Division of Labor and Cross-Feeding

Two particularly important ecological principles for engineering efficient microbial consortia are division of labor and cross-feeding. Division of labor occurs when different consortium members specialize in specific metabolic tasks, distributing the biochemical burden across the community [27] [29]. This specialization reduces the metabolic load on individual strains, allowing each to optimize its designated function without maintaining redundant pathways.

In the context of plastic upcycling, division of labor has been successfully implemented in a synthetic consortium involving two Pseudomonas putida strains. One strain specialized in terephthalic acid (TPA) utilization, while the other specialized in ethylene glycol (EG) consumption [29]. This strategic division allowed the consortium to simultaneously metabolize both primary products of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) hydrolysis, overcoming the carbon catabolite repression that often limits mixed-substrate utilization in single strains.

Cross-feeding represents another fundamental ecological principle where metabolites produced by one community member are utilized by another [28]. This interaction creates interdependence between consortium members and enhances community stability. For cross-feeding to be established, four requirements must be met: (1) compounds must be transferred from producer to receiver, (2) the transferred compounds must be taken up by the receiver or participate in energy conversion, (3) the fitness of both producer and receiver changes due to the acquired compounds, and (4) the interaction must involve different species or genotypes [28].

In plastic-degrading consortia, cross-feeding can occur when one member partially degrades the polymer into intermediate compounds that subsequent members further metabolize. This metabolic handoff enables the complete mineralization of complex plastics that would be difficult for any single microbe to degrade entirely [30].

Figure 1: Division of Labor in a Plastic-Degrading Microbial Consortium. This diagram illustrates how metabolic tasks are partitioned between specialist strains in a synthetic consortium designed for PET upcycling, demonstrating the ecological principle of division of labor.

Application Notes: Microbial Consortia for Plastic Degradation

Advantages of Consortia Over Single Strains

The application of microbial consortia for plastic degradation offers several significant advantages over single-strain approaches, largely derived from ecological principles that enhance functional efficiency and resilience. Synthetic microbial consortia demonstrate higher processing efficiencies because division of labor reduces the metabolic burden on individual members [28]. This distributed metabolic load allows each strain to specialize in its designated task without maintaining the genetic machinery for complete plastic degradation pathways.

When applied to plastic upcycling, consortia exhibit reduced catabolic crosstalk and achieve faster deconstruction, particularly at high substrate concentrations or when using crude hydrolysate [29]. For instance, a engineered consortium of two Pseudomonas putida strains showed superior performance in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) hydrolysate consumption compared to a single-strain counterpart engineered for the same purpose. The consortium achieved complete substrate assimilation of both terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG) within 48 hours, while monocultures struggled with mixed substrate utilization due to carbon catabolite repression [29].

Additional advantages of consortia approaches include:

- Enhanced metabolic versatility through complementary enzymatic activities [30]

- Improved adaptability to environmental fluctuations and heterogeneous substrates [28]

- Greater tolerance to inhibitory compounds present in plastic hydrolysates [29]

- Functional stability through ecological interactions that maintain community composition [27]

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance advantages of consortium-based approaches can be quantitatively demonstrated through comparative studies of plastic degradation efficiency.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Single Strain vs. Consortium Approaches for Plastic Upcycling

| Performance Metric | Single Strain (Pp-TE) | Two-Strain Consortium (Pp-T + Pp-E) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPA Consumption Rate | 56.2 mM in 48 hours [29] | 56.2 mM in 36 hours [29] | 25% faster |

| EG Consumption Rate | 56.2 mM in 36 hours [29] | 56.2 mM in 36 hours [29] | Comparable |

| Mixed Substrate Utilization | Impaired due to catabolite repression [29] | Simultaneous and complete utilization [29] | Significantly enhanced |

| High TPA Tolerance | Limited growth at 316 mM [29] | Robust growth at 316 mM [29] | Greatly improved |

| Crude Hydrolysate Utilization | Inhibited metabolism [29] | Efficient deconstruction [29] | More robust |

| mcl-PHA Production | Lower yield and productivity [29] | Enhanced yield and flexible tuning [29] | Improved |

These quantitative comparisons demonstrate that consortium-based approaches leverage ecological principles to overcome fundamental limitations of single-strain bioprocessing. The division of labor enables simultaneous utilization of mixed substrates without catabolite repression, while distributed metabolic functions enhance tolerance to inhibitory compounds present in plastic hydrolysates.

Protocols for Designing Plastic-Degrading Microbial Consortia

Consortium Construction Strategies

The construction of synthetic microbial consortia for plastic degradation follows distinct strategic approaches, each with specific methodologies and applications.

Figure 2: Strategic Approaches for Constructing Plastic-Degrading Microbial Consortia. The diagram illustrates top-down and bottom-up strategies for developing functional consortia, highlighting different starting points and methodological approaches.

Top-Down Construction Protocol

The top-down strategy involves establishing a stable co-cultivation system from complex natural microbial communities through selective enrichment techniques [28]. This approach leverages environmental selection pressure to evolve minimally active microbial consortia (MAMC) with desired plastic-degrading functions.

Protocol: Sequential Enrichment for Plastic-Degrading Consortia

Microcosm Establishment

- Collect environmental samples from plastic-contaminated sites (soil, marine sediment, landfill leachate)

- Bury target plastic material (e.g., LLDPE film) in 500 mL containers with 300 g of sample material

- Incubate for 3 months in the dark at 30°C, maintaining 40-50% humidity with bimonthly humidification [30]

Selective Enrichment

- Transfer 5 g of microcosm material to 250 mL flasks containing 50 mL minimal saline medium (MSM)

- Add target plastic (1% w/v powder or film pieces) as sole carbon source

- Incubate with shaking (120 rpm) at 30°C for 30 days [30]

Sequential Transfer

- Perform monthly transfers to fresh MSM with plastic substrate

- For powder-based enrichment: transfer 5 mL of previous culture

- For film-based enrichment: transfer plastic pieces from previous culture [30]

- Continue transfers until stable community structure is achieved (typically 3-5 transfers)

Community Analysis

- Monitor abundance and diversity of total bacteria and fungi throughout process

- Track ligninolytic microorganisms due to enzymatic similarity to plastic degradation [30]

- Identify key members through metagenomic sequencing and isolate dominant strains

This protocol typically results in reduced microbial diversity with each transfer, ultimately selecting for a specialized consortium adapted to utilize the target plastic as a carbon source [30].

Bottom-Up Construction Protocol

The bottom-up strategy involves rational assembly of known microbial strains based on metabolic principles to create defined synthetic consortia [28]. This approach offers greater control over community composition and enables precise engineering of metabolic interactions.

Protocol: Rational Design of Specialist Consortia

Strain Selection

- Identify microbial strains with complementary plastic-degrading capabilities

- Select for specific substrate specializations (e.g., TPA vs. EG degradation) [29]

- Choose strains with compatible growth requirements and environmental tolerances

Metabolic Engineering

- Enhance specialization by deleting competing metabolic pathways

- For TPA specialists: delete entire ped gene cluster to eliminate EG oxidation [29]

- For EG specialists: delete transcriptional repressor gclR and enhance glcDEF operon expression [29]

- Introduce heterologous degradation pathways when necessary (e.g., tpa cluster from Rhodococcus jostii) [29]

Consortium Assembly

- Establish co-culture conditions through inoculation ratio optimization

- Monitor population dynamics to ensure stability

- Implement environmental control parameters (temperature, pH) to maintain ecological balance [28]

Functional Validation

Monitoring and Analysis Protocols

Comprehensive monitoring and analysis are essential for characterizing the structure, function, and stability of plastic-degrading microbial consortia. The following protocols outline key methodologies for consortium validation.

Community Composition Analysis

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

- Extract community DNA using commercial kits with bead beating for cell lysis

- Amplify V3-V4 hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA gene

- Sequence on Illumina platform with 2×250 bp paired-end reads

- Process sequences using QIIME2 or MOTHUR for taxonomic assignment [31]

Strain-Level Differentiation

- Employ high-resolution algorithms to discriminate strain-level variants

- Utilize single nucleotide variant (SNV) analysis for closely related strains

- Apply gene presence/absence analysis for distinguishing genomic features [31]

Functional Activity Assessment

Metatranscriptomic Analysis

- Preserve RNA immediately upon sample collection using RNAlater or similar reagents

- Extract total RNA using protocols that efficiently recover microbial RNA

- Remove rRNA using depletion kits targeting bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA

- Prepare sequencing libraries and sequence on Illumina platform

- Map reads to reference genomes or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)

- Normalize transcript counts to corresponding DNA abundances to differentiate changes in transcription from population shifts [31]

Enzymatic Activity Profiling

Degradation Efficiency Quantification

Weight Loss Measurements

Polymer Characterization

- Analyze surface changes using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

- Assess chemical modifications through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Monitor molecular weight reduction via gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflow for developing and analyzing plastic-degrading microbial consortia requires specific reagents, materials, and methodologies. The following table comprehensively details these essential research components.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Consortium Development

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Protocol Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Media | Minimal Saline Medium (MSM) [30] | Selective enrichment with plastic as sole carbon source | Consortium selection and maintenance |

| Plastic Substrates | LLDPE powder (<500 μm) and film (1×1 cm) [30] | Target plastic for degradation studies | Selective enrichment and degradation assays |

| Polymer Types | Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), Linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) [30] [29] | Representative plastic polymers for degradation studies | Substrate specificity assessments |

| Analytical Tools | 16S rRNA sequencing primers (e.g., 515F/806R) [31] | Taxonomic profiling of consortium members | Community composition analysis |

| Enzyme Assays | Colorimetric substrates for lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase [30] | Quantification of key plastic-degrading enzymes | Functional screening of consortium members |

| Strain Engineering | CRISPR-Cas9 systems for Pseudomonas putida [29] | Genetic modification to enhance specialization | Creation of substrate specialists |

| Metabolic Modules | tpa cluster from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 [29] | Heterologous TPA degradation pathway | Engineering TPA specialists |

| Preservation Solutions | RNAlater stabilization solution [31] | RNA preservation for metatranscriptomic studies | Functional activity analysis |

| DNA/RNA Kits | Commercial extraction kits with bead beating [31] | Nucleic acid isolation from complex communities | Molecular analysis of consortia |

| N-(Azido-PEG3)-N-bis(PEG4-acid) | N-(Azido-PEG3)-N-bis(PEG4-acid), MF:C30H58N4O15, MW:714.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| N-(Azido-PEG4)-Biocytin | N-(Azido-PEG4)-Biocytin, MF:C27H47N7O9S, MW:645.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This comprehensive toolkit enables researchers to implement the full spectrum of protocols required for developing, optimizing, and characterizing plastic-degrading microbial consortia. The selection of appropriate reagents and materials is critical for achieving reproducible and meaningful results in consortium-based plastic biodegradation studies.

The strategic application of ecological principles to design and implement microbial consortia offers a powerful framework for addressing the complex challenge of plastic pollution. By understanding and engineering ecological interactions such as division of labor, cross-feeding, and metabolic specialization, researchers can develop consortia with enhanced plastic-degrading capabilities compared to single-strain approaches. The protocols outlined in this document provide a roadmap for constructing, monitoring, and optimizing these consortia through both top-down and bottom-up strategies.

As plastic pollution continues to accumulate worldwide, leveraging these ecological principles through synthetic microbial consortia represents a promising biotechnological approach for plastic waste management and upcycling. The continued refinement of these methodologies, coupled with advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, will undoubtedly yield even more efficient and versatile consortia for addressing this pressing environmental challenge.

Application Notes

This document provides detailed protocols for sourcing and utilizing plastic-degrading microbial consortia from agricultural waste composting and marine environments, supporting their application in synthetic biology and bioremediation research.

Microbial Sourcing from Agricultural Waste Composting

Background and Rationale Agricultural waste composting serves as a rich reservoir for ligninolytic microorganisms whose enzymatic machinery (laccases, peroxidases) is also effective against synthetic plastic polymers. The complex, thermophilic environment selects for robust, versatile degraders capable of breaking down recalcitrant organic materials, making this niche particularly promising for sourcing plastic-degrading consortia [4]. The inherent metabolic diversity in these communities enables synergistic interactions that can be harnessed for more complete plastic mineralization compared to single-isolate approaches [8].

Key Microbial Taxa Compost-derived consortia are typically dominated by bacterial genera Bacillus and Pseudomonas, alongside fungal species such as Fusarium [4]. These microorganisms produce extracellular enzymes including cutinases, laccases, and multicopper oxidases that initiate plastic polymer breakdown through surface erosion and hydrolysis mechanisms [8].

Quantitative Performance Metrics Table 1: Degradation Performance of Compost-Derived Consortia

| Polymer Type | Consortium Composition | Degradation Rate | Experimental Conditions | Key Enzymes Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLDPE | Bacillus, Fusarium, Pseudomonas mix | Quantitative weight loss data pending | Agricultural composting conditions | Laccases, cutinases, peroxidases |

| PET | Ligninolytic compost community | Quantitative weight loss data pending | Laboratory simulation of composting | Cutinases, esterases |

| Film Plastics | Versatile consortium from composting | Quantitative weight loss data pending | Temperature-phased incubation | Multicopper oxidases, hydrolases |

Marine Environment Microbial Sourcing

Background and Rationale Marine ecosystems represent an underexplored frontier for discovering novel plastic-degrading enzymes, with microorganisms adapted to diverse conditions from surface waters to extreme deep-sea habitats [32]. The plastisphere – microbial communities colonizing plastic surfaces in aquatic environments – provides a natural selection environment for bacteria and fungi with plastic-degrading capabilities [33]. Marine-derived enzymes often display unique catalytic properties reflecting their ecological niches, including cold-adaptation and halotolerance [32].

Key Microbial Taxa and Enzymes Marine plastic-degrading communities include psychrophilic (cold-adapted) bacteria such as Oleispira antarctica producing cold-active esterases, and deep-sea isolates from hydrothermal vents and abyssal plains [32]. The most extensively studied marine plastic-degrading enzymes include PET hydrolases (EC 3.1.1.101), cutinases (EC 3.1.1.74), and carboxylesterases (EC 3.1.1.1) that hydrolyze ester bonds in polyesters like PET and PLA [32].

Quantitative Performance Metrics Table 2: Degradation Performance of Marine Microbial Systems

| Polymer Type | Source Environment | Degradation Efficiency | Time Frame | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHBH (Polyhydroxyalkanoate) | Deep-sea floor (855m depth) | 52% weight loss | 8 months | In situ, 2-6°C |

| PHBH (Polyhydroxyalkanoate) | Shore (Port, 2-6m depth) | ~700 μm thickness reduction | 1 year | In situ |

| PHA, Biodegradable Polyesters | Multiple deep-sea sites (757-5552m) | Degradation confirmed, rate decreases with depth | Varies by site | Deep-sea floor conditions |

| PET | Marine isolates | Varies by enzyme; enhanced via protein engineering | Hours to days | Laboratory assays |

| PLA | Marine enzymatic resources | Up to 90% degradation reported in optimized systems | 10 hours | Laboratory conditions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enrichment and Isolation of Plastic-Degrading Consortia from Agricultural Compost

Principle This method utilizes selective enrichment on plastic polymers as the sole carbon source to isolate microbial consortia with plastic-degrading capabilities from agricultural compost [4].

Materials

- Fresh agricultural waste compost sample (≥100g)

- Minimal salts medium (MSM)

- Target plastic polymers (LLDPE, PET, or PLA powders/films)

- Sterile Erlenmeyer flasks (250mL)

- Orbital shaker incubator

- Laminar flow hood

- Sterile filtration apparatus (0.22μm filters)

Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 100g fresh compost with 100mL sterile MSM. Shake at 150rpm for 30min at 30°C.

- Initial Enrichment: Filter through sterile muslin cloth. Add 10mL filtrate to 90mL MSM containing 1% (w/v) target plastic polymer as sole carbon source.

- Incubation: Incubate at 30°C with shaking at 150rpm for 14 days.

- Subculturing: Transfer 10% (v/v) culture to fresh MSM with plastic every 14 days for 3 cycles.

- Consortium Characterization: Analyze community composition via 16S rRNA and ITS sequencing.

- Degradation Assessment: Monitor plastic weight loss, surface changes via SEM, and chemical changes via FTIR.

Quality Control

- Maintain sterile controls without inoculum

- Monitor contamination regularly

- Validate degradation through multiple analytical methods

Protocol 2: Collection and Processing of Marine Plastic-Associated Microbiomes

Principle This protocol details the in situ collection of plastic-associated microbial communities from marine environments, including deep-sea locations, for discovering novel plastic-degrading microorganisms [34] [33].

Materials

- Custom sample holders and mesh bags

- Research vessel with sampling capability (e.g., HOV Shinkai 6500 for deep-sea)

- Sterile collection containers

- Formaldehyde solution (4% in filtered seawater) for fixation

- Filtration apparatus

- DNA extraction kits

Procedure

- Substrate Deployment: Prepare plastic substrates (LLDPE, PET, PLA, OXO) as paddles (75×50×3mm). Include artificially aged and virgin materials [33].

- In Situ Incubation: Deploy substrates at target depths (20-60cm in wastewater ponds; 757-5552m for deep-sea) using secured structures [34] [33].

- Sample Collection: Retrieve substrates at predetermined intervals (2, 6, 26, 52 weeks).

- Biomass Recovery: Scrape biofilms with sterile razor blades followed by sonication to dislodge residual biomass.

- Community Analysis: Process for 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, and ITS sequencing to characterize prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities.

- Functional Screening: Screen for plastic-degrading potential through cultivation-dependent and independent approaches.

Quality Control

- Deploy control substrates (glass)

- Record environmental parameters (temperature, light intensity)

- Process controls in parallel to detect contamination

Protocol 3: Engineering Synthetic Microbial Consortia with Division of Labor

Principle This protocol describes the rational design of synthetic microbial consortia that employ division of labor to efficiently degrade mixed plastic hydrolysates, overcoming metabolic limitations of single strains [29].

Materials

- Specialized Pseudomonas putida strains (Pp-T for TPA degradation; Pp-E for EG degradation)

- PET hydrolysate (containing TPA and EG)

- Fermentation equipment

- Genetic engineering tools (CRISPR, plasmids)

- Analytical instruments (HPLC, GC-MS)

Procedure

- Strain Development:

- For TPA specialist (Pp-T): Delete ped gene cluster to eliminate EG oxidation. Introduce tpa cluster from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 for TPA conversion to PCA [29].

- For EG specialist (Pp-E): Delete gclR transcriptional repressor. Replace native promoter and RBS of glcDEF operon with strong constitutive promoter (Ptac) and artificial RBS [29].

Consortium Assembly:

- Co-culture Pp-T and Pp-E strains in defined ratio (optimize between 1:1 to 1:3).

- Use PET hydrolysate as substrate in minimal medium.

Performance Monitoring:

- Track TPA and EG consumption via HPLC.

- Monitor biomass growth (OD600).

- Quantify metabolic intermediates.

Application to Product Synthesis:

- Engineer strains for polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) or cis,cis-muconate (MA) production.

- Modulate population ratios to optimize product yields.

Quality Control

- Compare consortium performance against single-strain controls

- Monitor genetic stability of engineered strains

- Validate orthogonality of metabolic pathways

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for sourcing and engineering plastic-degrading consortia from agricultural compost and marine environments.

Diagram 2: Metabolic division of labor in engineered consortium for PET upcycling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plastic Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Salts Medium (MSM) | Selective enrichment of plastic-degrading microbes | Contains essential minerals without carbon sources to force plastic utilization |

| Polymer Substrates | Selection pressure for degraders | LLDPE, PET, PLA, OXO plastics as powders, films, or standardized paddles |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Community analysis of plastisphere | Commercial kits optimized for environmental samples with inhibitory substances |

| 16S/18S/ITS Primers | Amplicon sequencing of communities | Target variable regions for prokaryotic (16S), eukaryotic (18S), and fungal (ITS) diversity |

| PET Hydrolysate | Substrate for engineered consortia | Contains terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG) in typical PET ratios |

| HPLC/GC-MS Systems | Quantifying substrate consumption and product formation | Reverse-phase HPLC for TPA/EG; GC-MS for metabolic intermediates |

| SEM Instrumentation | Visualizing surface degradation | Scanning electron microscopy to detect erosion patterns and biofilm formation |

| FTIR Spectrometer | Detecting chemical changes in polymers | Identifies bond breakage and formation of functional groups during degradation |

| N-(Biotin)-N-bis(PEG1-alcohol) | N-(Biotin)-N-bis(PEG1-alcohol), MF:C18H33N3O6S, MW:419.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Danuglipron Tromethamine | Danuglipron Tromethamine|PF-06882961|For Research |

Concluding Remarks

The strategic sourcing of plastic-degrading microbes from agricultural compost and marine environments provides diverse enzymatic toolkits for tackling plastic pollution. When integrated into rationally designed synthetic consortia employing division of labor, these microbial communities demonstrate enhanced degradation capabilities, particularly for mixed plastic waste streams. The protocols outlined herein establish standardized approaches for harnessing these biological resources, supporting advances in plastic bioremediation and upcycling within a circular economy framework.

Designing and Implementing Effective Plastic-Degrading Microbial Communities

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Approaches for Consortium Assembly

The assembly of functional microbial consortia represents a cornerstone in advancing biotechnology for environmental remediation, including plastic degradation. Researchers primarily employ two distinct philosophical approaches: top-down and bottom-up. The top-down approach involves applying selective environmental pressures to steer a natural microbial community toward a desired function, such as plastic degradation [35]. Conversely, the bottom-up approach involves the rational design and construction of a new consortium by assembling well-characterized native or engineered microorganisms based on prior knowledge of their metabolic pathways and potential interactions [35] [36]. The choice between these strategies significantly impacts the consortium's stability, controllability, and functional efficacy, making the understanding of their respective protocols and applications essential for researchers in the field of plastic biodegradation.

Comparative Analysis: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Approaches

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges associated with top-down and bottom-up consortium assembly strategies.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of top-down and bottom-up approaches for microbial consortium assembly.

| Feature | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Selective steering of natural microbial communities via environmental variables [35]. | Rational assembly of individual, known microbes into a new synthetic consortium [35] [36]. |

| Design Complexity | Low initial design complexity; leverages natural biodiversity. | High design complexity; requires deep prior knowledge of member physiology and ecology. |

| Control & Predictability | Lower control and predictability; complex interactions are difficult to disentangle [35]. | Higher degree of control over composition and function; more predictable outcomes [35]. |

| Stability & Robustness | Often highly robust and stable due to natural selection. | Challenges remain in maintaining long-term stability due to unpredictable internal dynamics [35]. |

| Key Challenges | Difficulties in manipulating complex community structures and functions [35]. | Optimal assembly and long-term stability of the defined consortium [35]. |

| Ideal Use Cases | Waste valorization (e.g., anaerobic digestion), bioremediation where complex substrates are used [35]. | Targeted bioprocesses for high-value product synthesis (e.g., biofuels, therapeutics), engineered pathways [35] [6]. |

Application Notes for Plastic Degradation Research

Within the context of plastic degradation, both assembly strategies are being actively explored and refined. Polyethylene (PE), characterized by its high molecular weight and stable carbon-carbon backbone, presents a significant challenge for biodegradation [37]. The microbial degradation process generally follows several stages: colonization, biodeterioration, biofragmentation, assimilation, and mineralization [37].

Top-Down Enrichment Protocol for PE-Degrading Consortia

This protocol outlines the enrichment of a native microbial consortium capable of polyethylene degradation from environmental samples, such as soil from landfills or the "plastisphere" – the unique microbial community that develops on plastic surfaces in the environment [37].

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect plastic debris or plastic-contaminated soil from a target environment (e.g., landfill, marine shore, recycling center).

- Inoculum Preparation: Homogenize 10 g of the sample in 100 mL of sterile minimal salt medium (MSM).

- Enrichment Culture:

- Use a carbon-free MSM to force selection of microbes capable of utilizing plastic as their primary carbon source.

- Supplement the medium with sterile PE powder or a small, sterile PE film as the sole carbon source.

- Inoculate the medium with 5% (v/v) of the prepared inoculum.

- Selective Pressure & Sub-Culturing:

- Incubate the culture under optimal conditions (e.g., 30°C, 150 rpm agitation) for 4-8 weeks.

- Periodically sub-culture (e.g., every 4 weeks) 10% (v/v) of the enriched culture into fresh MSM with fresh PE.

- Repeat this sub-culturing process at least 5 times to selectively enrich the PE-degrading populations.