Metagenomic Insights into Coastal Extracellular Enzymes: From Microbial Ecology to Biomedical Potential

This article explores the transformative role of metagenomics in deciphering the diversity, function, and dynamics of extracellular enzymes in coastal waters.

Metagenomic Insights into Coastal Extracellular Enzymes: From Microbial Ecology to Biomedical Potential

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of metagenomics in deciphering the diversity, function, and dynamics of extracellular enzymes in coastal waters. Coastal ecosystems are hotspots of microbial activity where extracellular enzymes drive essential biogeochemical cycles by degrading complex organic matter. We examine how metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches are unraveling the vast genetic potential of uncultured microbial communities, revealing novel enzymes with implications for nutrient cycling, environmental monitoring, and drug discovery. The content covers foundational concepts of marine enzyme ecology, advanced methodological frameworks for functional profiling, strategies for overcoming analytical challenges, and comparative assessments of enzyme systems across diverse coastal habitats. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how coastal metagenomics serves as a pipeline for discovering biologically active enzymes with therapeutic and industrial applications, from antibiotic resistance mechanisms to novel biocatalysts.

The Hidden World of Coastal Extracellular Enzymes: Fundamentals and Ecological Significance

Extracellular enzymes are fundamental functional components of marine ecosystems, initiating the critical first step in the biogeochemical cycling of organic matter by catalyzing the degradation of complex macromolecules into smaller, bioavailable substrates [1]. In marine environments, where an estimated 50% of surface primary production is processed through the microbial loop, these enzymes enable the transformation, repackaging, and respiration of organic compounds [1]. Most marine dissolved organic matter (DOM) exists as chemically complex polymers that are too large to cross cell membranes and must be hydrolyzed into molecules typically smaller than 600 Da by extracellular enzymes before microbial uptake can occur [1]. Measuring in situ seawater extracellular enzyme activity (EEA) thus provides fundamental information for understanding the organic carbon cycle and energy flow in the ocean [1]. The study of these enzymes, particularly through modern metagenomic approaches, is essential for elucidating the mechanisms underlying organic matter remineralization and the functional roles of marine microbial communities in coastal waters.

Quantitative Data on Marine Extracellular Enzymes

The activity and distribution of extracellular enzymes are key indicators of microbial functional diversity and biogeochemical processes. The tables below summarize core quantitative findings and major enzyme-producing taxa identified in marine environments.

Table 1: Key Hydrolytic Enzyme Activities in Chinese Marginal Seas (adapted from [1])

| Enzyme Type | Primary Substrate | Reported Contribution to Summed Hydrolysis Rates | Key Environmental Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatase | Organic Phosphorus | High | Nutrient acquisition, phosphate cycling |

| β-Glucosidase | Cellulose & β-linked polysaccharides | High | Carbon cycling, polysaccharide degradation |

| Protease | Proteins & Peptides | High | Nitrogen acquisition, protein degradation |

| Chitinase | Chitin | Variable (Substrate-dependent) | Degradation of crustacean/exoskeleton debris |

| Alginate Lyase | Alginate (Brown Algae) | Variable (Substrate-dependent) | Degradation of algal biomass |

Table 2: Major Marine Enzyme Classes and Their Industrial Relevance (adapted from [2] [3])

| Enzyme Class | Primary Function | Industrial/Biotechnological Application | Market Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteases | Hydrolyze peptide bonds in proteins | Detergents, leather processing, pharmaceuticals, food processing | Largest market share (42% in 2024) [3] |

| Lipases | Hydrolyze triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol | Biofuels (biodiesel), nutraceuticals, food processing, diagnostics | Fastest-growing segment (CAGR 10.2%) [3] |

| Carbohydrases | Degrade complex carbohydrates (e.g., chitin, alginate, agar) | Biofuels, prebiotics, functional foods, cosmetics | Essential for marine polysaccharide processing [2] |

| Oxidoreductases | Catalyze redox reactions | Biosensors, bioremediation, chemical synthesis | Used in breaking down environmental pollutants [3] |

Table 3: Identified Marine Enzyme-Producing Microbial Clades (adapted from [1])

| Microbial Clade | Type | Examples of Enzymes Produced |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidetes | Bacteria | Proteases, polysaccharide-degrading enzymes (e.g., agarases) |

| Planctomycetes | Bacteria | - |

| Chloroflexi | Bacteria | - |

| Roseobacter | Bacteria (Alphaproteobacteria) | - |

| Alteromonas | Bacteria (Gammaproteobacteria) | - |

| Pseudoalteromonas | Bacteria (Gammaproteobacteria) | - |

| Streptomyces | Actinobacteria | Phospholipase C [2] |

| Aureobasidium pullulans | Yeast/Fungus | Proteases, Lipases [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Extracellular Enzyme Activity

This section provides a detailed methodology for measuring extracellular enzyme activity (EEA) in coastal water samples, a core technique for ecological studies and metagenomic validation.

Protocol: Sampling and Concentration of Extracellular Enzymes

Principle: To concentrate low-abundance extracellular enzymes from seawater for activity measurements, enabling the detection and quantification of hydrolysis rates on natural high-molecular-weight (HMW) polymers [1].

Materials:

- Water Sampling Bottles/Niskin Bottles: For collecting seawater samples.

- Prefiltration System: 20-μm pore-size filters (e.g., Millipore) to remove large particles and organisms.

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System: Equipped with 5000-Dalton molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) hollow-fiber or modified polyethersulfone membranes (e.g., Spectrum Laboratories) [1].

- Sterile Collection Vessels: For concentrated samples.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect surface water (e.g., from ~2 m depth) using a submersible pump or Niskin bottle [1].

- Prefiltration: Gently pass a known volume of seawater (e.g., 10 L) through a 20-μm filter to eliminate large particulates [1].

- Enzyme Concentration: Concentrate the prefiltered seawater (e.g., from 10 L to 50 mL) using the TFF system. Complete this process within 2 hours of sample collection to preserve enzyme activity [1].

- Fractionation (Optional): To separate dissolved from cell-associated enzymes, gently filter a portion of the concentrated sample (e.g., 25 mL) through a 0.22-μm syringe filter (e.g., Millipore Millex-GP) [1].

- Storage: Store processed samples at 4°C and begin enzyme assays within 1 hour in an onboard or nearby laboratory [1].

Protocol: Measuring Hydrolysis Rates Using Fluorogenic Substrates

Principle: The hydrolysis of a model substrate releases a fluorescent tag, the accumulation of which is measured over time to calculate enzyme activity. This method can be adapted for various enzyme classes.

Materials:

- Fluorogenic Substrates: e.g., 4-Methylumbelliferyl (MUF)- or 7-Amido-4-methylcoumarin (AMC)-linked substrate analogs (e.g., MUF-phosphate for phosphatases, MUF-β-D-glucoside for β-glucosidases) [1].

- Microplate Reader: Capable of measuring fluorescence (e.g., excitation/emission ~365/450 nm for MUF).

- Incubation Chamber: Temperature-controlled to maintain in situ or standardized conditions (e.g., 25°C) [1].

- Buffers and Stop Solutions: Appropriate buffers (e.g., Tris, PIPES) for pH control; a basic stop solution (e.g., 10 mM NaOH) can enhance fluorescence stability.

Procedure:

- Substrate Addition: Add a saturating concentration of the fluorogenic substrate to the concentrated seawater sample or its fractions in a multi-well plate or cuvette. Using high substrate concentrations ensures the measurement of potential enzyme activity [1].

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C or ambient sea surface temperature). To study temperature effects, a higher temperature (e.g., 35°C) can be used [1].

- Measurement: Monitor the increase in fluorescence at regular intervals over the course of the incubation (e.g., 30 minutes to several hours).

- Calculation: Calculate the hydrolysis rate from the slope of the fluorescence versus time curve, using a standard curve of the free fluorophore (e.g., MUF) for quantification. Report activity as moles of substrate hydrolyzed per unit volume per unit time (e.g., nmol Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹).

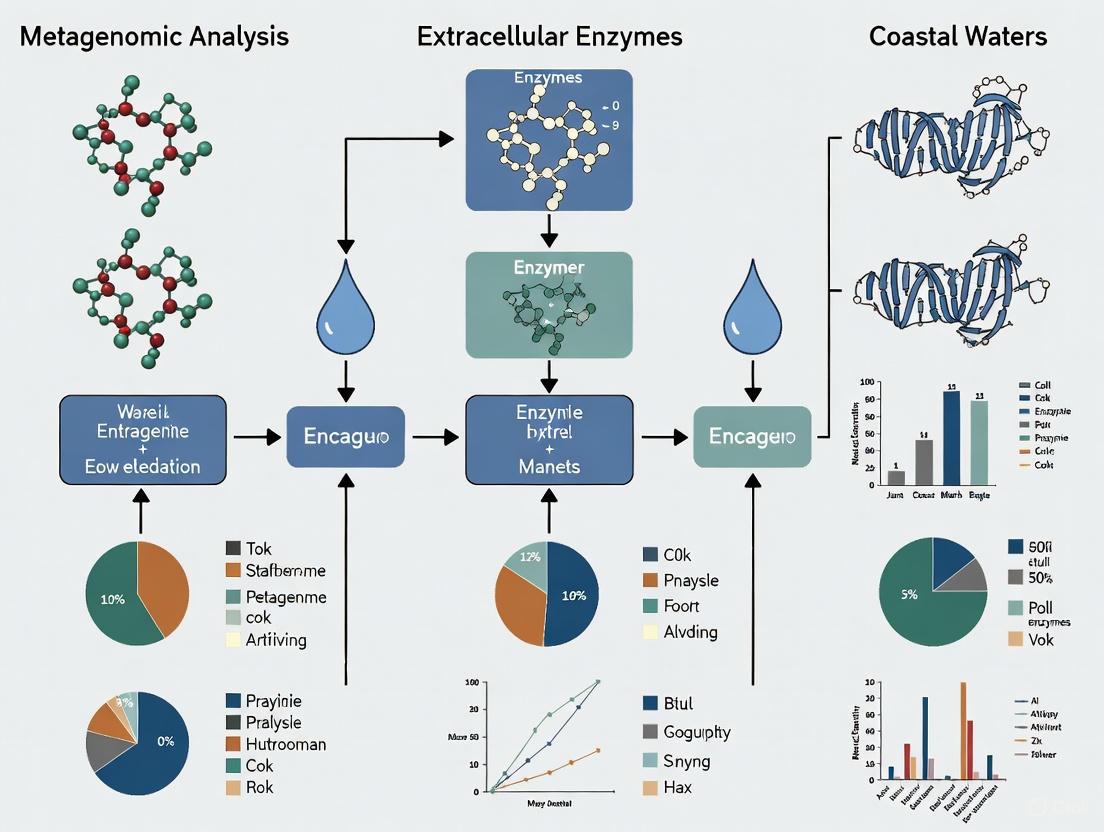

Visualization of Extracellular Enzyme Ecology

The following diagram illustrates the sources, pools, and ecological roles of extracellular enzymes in the marine environment, highlighting their connection to metagenomic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential reagents, materials, and technologies for conducting research on extracellular enzymes in marine systems, with a focus on metagenomic-linked ecological studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Marine EEA Studies

| Item | Specific Examples & Specifications | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates | 4-Nitrophenyl (pNP) or 4-Methylumbelliferyl (MUF)-linked analogs (e.g., MUF-phosphate, MUF-β-glucoside) [1] | Proxy substrates for measuring potential hydrolysis rates of specific enzyme classes (e.g., phosphatases, glucosidases). |

| Natural Polymer Substrates | Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), chitin, alginic acid, casein [1] | Measuring hydrolysis rates of environmentally relevant biopolymers to approximate in situ degradation. |

| Filtration Systems | 20-μm filters for pre-filtration; 0.22-μm polycarbonate membranes for separating cell-associated fractions; Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) with 5-kDa membranes [1] | Concentrating dilute enzymes from large water volumes and separating dissolved from cell-associated enzyme fractions. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Kits optimized for environmental samples (e.g., from filters); protocols including lysozyme and Proteinase K digestion [4] | Extracting high-quality microbial DNA from water or concentrated samples for subsequent metagenomic sequencing. |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Services/Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq (e.g., 2x151 bp chemistry) [4] | Determining the taxonomic and functional gene composition (e.g., CAZymes, peptidases) of the microbial community. |

| Bioinformatics Software & Databases | BBTools (BBDuk, bbmap), metaSPAdes assembler, Prodigal for gene prediction, NCBI protein database, KEGG [5] [4] | Processing raw sequencing data, assembling metagenomes, predicting genes, and annotating enzyme functions and pathways. |

| (R)-carnitinyl-CoA betaine | (R)-carnitinyl-CoA betaine, MF:C28H49N8O18P3S, MW:910.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11-Keto-9(E),12(E)-octadecadienoic acid | 11-Keto-9(E),12(E)-octadecadienoic acid, MF:C18H30O3, MW:294.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Coastal waters are dynamic biochemical reactors where microbial communities play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling and organic matter degradation. Central to these processes are extracellular enzymes, including hydrolases, lipases, and phosphatases, which enable microorganisms to break down complex polymers into assimilable substrates. Metagenomic analysis of these enzymes provides a powerful lens for understanding microbial community function and ecological dynamics without the need for cultivation [6] [7]. This application note details the key methodologies and reagents for studying these critical enzyme classes within a metagenomic framework, providing researchers with standardized protocols for assessing microbial community functional potential in coastal ecosystems.

Key Enzyme Classes: Functions and Ecological Roles

Hydrolases and Lipases

Hydrolases catalyze the hydrolytic cleavage of ester bonds in the presence of water, and in low-water conditions can catalyze synthetic reactions like esterification and transesterification [6]. This enzyme class is characterized by a conserved catalytic triad of serine, aspartate (or glutamate), and histidine residues, with the catalytic serine embedded in the consensus motif Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly [6].

- Lipases vs. Esterases: While both are lipolytic enzymes, they differ in substrate specificity. Esterases hydrolyze short-chain fatty acid esters (<12 carbon atoms), while true lipases (EC 3.1.1.3) prefer long-chain fatty acid esters (≥12 carbon atoms) and often exhibit interfacial activation where a lid covering the active site opens at lipid interfaces [6].

- Bacterial lipolytic enzymes are classified into eight families (I-VIII) based on amino acid sequences and biological properties, with additional families discovered through metagenomic approaches [6].

Phosphatases

Phosphatases catalyze the liberation of orthophosphate from organophosphates through hydrolytic dephosphorylation [8]. They are crucial for phosphorus cycling in phosphorus-limited coastal environments [9].

- Classification: Based on optimum pH, phosphatases are categorized as alkaline phosphatases (AKP) or acid phosphatases (ACP). Based on substrate specificity, they include phosphomonoesterase, phosphodiesterase, and phosphotriesterase [8].

- Genetic Determinants: Key alkaline phosphatase encoding genes include

phoA(phosphomonoesterase in Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi),phoDandphoX(target both phosphate monoesters and diesters in Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Cyanobacteria) [8].

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes in Coastal Waters: Functions and Genetic Markers

| Enzyme Class | EC Number | Primary Function | Substrate Preference | Key Gene Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Lipases | EC 3.1.1.3 | Hydrolysis of triacylglycerols | Long-chain fatty acid esters (≥12 C) | Families I-VIII (bacterial) |

| Esterases | EC 3.1.1.1 | Hydrolysis of carboxylic esters | Short-chain fatty acid esters (<12 C) | Families I-VIII (bacterial) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | EC 3.1.3.1 | Organic phosphorus mineralization | Phosphate monoesters/diesters | phoA, phoD, phoX |

| Acid Phosphatase | EC 3.1.3.2 | Organic phosphorus mineralization | Phosphate monoesters | Various, less studied |

Quantitative Data on Environmental Responses

Environmental factors significantly influence enzyme activities and gene abundance in coastal waters. Microplastics and antibiotics pollution can alter microbial community structure and function.

- Microplastics Impact: A 60-day sediment simulation study showed that microplastics (PE, PP, PS, PVC, PET) significantly reduced total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) content, while enhancing alkaline phosphatase activity. They also inhibited ammonia assimilation and methane synthesis processes [10].

- Antibiotics Impact: Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) exposure increased phosphatase activity and elevated the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) including

sul1,sul2,dfrA, andermF[10]. - Phosphorus Source Influence: Microbial communities respond differently to phosphorus sources. Inorganic phosphates (IP) and cyclic-nucleoside-monophosphates (cNMP) supported the highest total organic carbon (TOC) removal efficiencies (64.8% and 52.3%, respectively). IP treatments encouraged Enterobacter, while cNMP treatments encouraged Aeromonas [8]. The abundance of

phoAandphoUgenes was higher in IP treatments, whereasphoDandphoXgenes dominated organophosphate (OP) treatments [8].

Table 2: Environmental Influences on Enzyme Activity and Microbial Community Structure

| Environmental Stressor | Impact on Enzyme Activity | Impact on Microbial Community/Genes | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microplastics Mix (PE, PP, PS, PVC, PET) | Enhanced alkaline phosphatase activity; Reduced TC and TN | Inhibited ammonia assimilation & methane metabolism; Minimal impact on ARGs | Coastal sediments, 60-day exposure [10] |

| Antibiotic (Sulfamethoxazole) | Increased FDA hydrolase activity | Increased abundance of sul1, sul2, dfrA, ermF genes |

Coastal sediments, 60-day exposure [10] |

| Inorganic Phosphorus (IP) | Not specified | Higher abundance of phoA, phoU genes; Encouraged Enterobacter |

Activated sludge, 72h cultivation [8] |

| Organophosphorus (OP) | Not specified | Higher abundance of phoD, phoX genes |

Activated sludge, 72h cultivation [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Analysis from Coastal Sediments

Protocol Objective: To extract and analyze metagenomic DNA from coastal sediments for the identification of hydrolase, lipase, and phosphatase genes.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sediment samples from coastal regions (e.g., Liaodong Bay, Bohai Sea)

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., MO BIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit)

- Phosphorus-free M9 medium for enrichment cultures [8]

- Phenotype Microarray plates (e.g., PM4A Microplate, Biolog Inc.) for testing phosphorus source utilization [8]

- PCR reagents and primers for target genes (e.g.,

phoD,phoX, lipase families) - High-throughput sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina)

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect sediment cores from the desired coastal region. Store immediately at -80°C for DNA analysis or at 4°C for enrichment cultures.

- DNA Extraction: Extract total community DNA from 0.25-0.5 g of sediment using a commercial DNA isolation kit, following manufacturer's instructions.

- Enrichment Cultivation (Optional): For functional screening, inoculate sediment slurry into phosphorus-free M9 medium supplemented with different phosphorus sources (IP, NMP, cNMP, OP) as in PM4A Microplates. Incubate at in situ temperature (e.g., 30°C) for 3 days [8].

- Gene Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify target genes using degenerate primers. For lipases/esterases, target conserved regions around the catalytic triad. For phosphatases, use group-specific primers (e.g., for

phoD,phoX). - Sequencing & Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing. Process reads via quality filtering, assembly/or binning, and predict open reading frames. Annotate genes against databases (e.g., NCBI NR, KEGG, COG) using BLAST-based searches.

- Quantitative Analysis: Quantify gene abundance via read mapping or perform qPCR for specific gene targets.

Measuring Alkaline Phosphatase Activity (APA) in Water and Sediment

Protocol Objective: To quantify alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) as a measure of microbial phosphorus acquisition effort.

Materials & Reagents:

- Artificial substrate: 4-Methylumbelliferyl phosphate (MUF-P) or p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP)

- Buffer: Tris-HCl (pH 8-9 for alkaline phosphatase)

- Fluorescence microplate reader or spectrophotometer

- Calibration standards (e.g., MUF or pNP)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Filter water samples (0.2 µm) or create slurries with surface sediments and sterile-filtered water.

- Reaction Setup: Add artificial substrate (e.g., 200 µM MUF-P final concentration) to samples and controls (substrate blank, sample blank). Incubate in the dark at in situ temperature.

- Measurement: For MUF-P, measure fluorescence ( excitation ~365 nm, emission ~445 nm) at time zero and regularly over 1-3 hours. For pNPP, measure absorbance at 410 nm.

- Calculation: Calculate enzyme activity from the linear increase in product concentration over time, normalized to sample volume or chlorophyll-a content.

Visualizing the Workflow: From Sample to Functional Insight

The following diagram outlines the core metagenomic workflow for analyzing extracellular enzymes in coastal waters, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Metagenomic Analysis of Extracellular Enzymes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metagenomic Enzyme Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Microarray (PM4A) | High-throughput profiling of microbial community utilization of 59 different phosphorus sources [8]. | Identifying preferential phosphorus sources (IP, cNMP, OP) and linking them to specific phosphatase gene abundance (phoA, phoX) [8]. |

| MUF/P substrates | Fluorogenic enzyme substrates (e.g., MUF-phosphate, MUF-acetate, MUF-fatty acid esters). | Quantifying hydrolytic enzyme activities (phosphatase, esterase) in environmental samples via fluorescence measurement [8]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol | Traditional method for high-quality DNA extraction from complex environmental matrices. | Extracting metagenomic DNA from coastal sediments for subsequent sequencing and functional gene analysis [10]. |

| Commercial DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., MO BIO PowerSoil) | Standardized protocol for efficient lysis and purification of community DNA from soils and sediments. | Obtaining high-quality, PCR-ready metagenomic DNA for amplicon or shotgun sequencing of hydrolase genes [10]. |

| Degenerate Primers | Amplification of diverse gene families (e.g., bacterial lipase families I-VIII) from metagenomic DNA. | Screening environmental DNA for novel lipolytic enzymes from uncultured microorganisms [6]. |

| 13-Oxo-9E,11E-octadecadienoic acid | 13-Oxo-9E,11E-octadecadienoic acid, CAS:31385-09-8, MF:C18H30O3, MW:294.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (E)-2-benzylidenesuccinyl-CoA | (E)-2-Benzylidenesuccinyl-CoA Research Grade | Research-grade (E)-2-Benzylidenesuccinyl-CoA, an intermediate in anaerobic toluene degradation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Spatial and Temporal Dynamics in Enzyme Distribution and Activity

This application note provides a detailed framework for investigating the spatial and temporal dynamics of extracellular enzyme activities in coastal marine environments, contextualized within a broader metagenomic analysis research thesis. Extracellular enzymes are functional components of marine microbial communities that catalyze the degradation of organic substrates, playing a critical role in nutrient remineralization and biogeochemical cycling [11]. In coastal waters, these enzymes exhibit significant variations across short temporal and spatial scales, directly influencing primary production and microbial loop dynamics [11] [12]. This document presents standardized protocols for assessing enzyme activities, data on observed dynamics, and essential methodological considerations for researchers investigating microbial ecology in coastal systems.

Temporal Dynamics of Extracellular Enzyme Activities

Observed Patterns of Variation

Temporal variability in extracellular enzyme activity occurs across multiple timescales, from diurnal to seasonal patterns. Research from the MICRO time series in Newport Pier, California, demonstrated that 34-48% of the variation in enzyme activity occurs at timescales shorter than 30 days [11]. Approximately 28-56% of the variance in related parameters including nutrient concentrations, chlorophyll levels, and ocean currents also occurs on these short timescales [11].

Diurnal fluctuations can be particularly dramatic, with studies in Mediterranean coastal waters showing that α- and β-glucosidase activities varied by 0-100% within 24-hour periods [12]. In contrast, aminopeptidase activities exhibited weaker diurnal variation but substantial day-to-day changes comparable in magnitude to seasonal variations [12].

Seasonal patterns are enzyme-specific, with β-glucosidase showing repeatable seasonal patterns correlated with spring phytoplankton blooms in the Southern California Bight [11]. These temporal dynamics reflect rapid responses of microbial communities to environmental triggers including phytoplankton blooms, upwelling events, wind patterns, and rainfall [11].

Key Environmental Correlations

Statistical analyses reveal significant relationships between enzyme activities and environmental parameters:

- Nutrient correlations: Most enzyme activities show weak but positive correlations with nutrient concentrations (r = 0.24-0.31) [11].

- Upwelling influence: Enzyme activities correlate with upwelling dynamics (r = 0.29-0.35) [11].

- Temperature effects: Seagrass coverage and aboveground biomass show significant positive correlations with temperature in coastal ecosystems [13].

- Oxygen and COD relationships: Seagrass density demonstrates significant positive correlation with dissolved oxygen (DO) but significant negative correlation with chemical oxygen demand (COD) [13].

Table 1: Temporal Variation Patterns in Coastal Enzyme Activities

| Enzyme | Short-term Variation (<30 days) | Diurnal Variation | Seasonal Pattern | Primary Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-glucosidase | 34-48% of total variation [11] | 0-100% fluctuation observed [12] | Elevated in spring blooms [11] | Phytoplankton blooms, upwelling [11] |

| Aminopeptidase | Similar magnitude to seasonal scale [12] | Weak diurnal variation [12] | Not specifically reported | Nutrient concentrations [11] |

| α-glucosidase | Not specifically quantified | 0-100% fluctuation observed [12] | Not specifically reported | Not specified in search results |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Part of <30 day variation cohort [11] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Phosphate limitation [11] |

Spatial Distribution and Partitioning of Enzymes

Particle-Associated versus Free Enzymes

A crucial aspect of spatial distribution involves the partitioning of enzyme activities between particulate and dissolved phases. Research indicates distinct patterns across different enzyme types:

- Particle-dominated enzymes: For β-glucosidase and leucine aminopeptidase, most activity is bound to particles [11]. This localization potentially benefits enzyme producers by directly coupling hydrolysis with nutrient uptake [11].

- Freely dissolved enzymes: In contrast, 81.2% of alkaline phosphatase and 42.8% of N-acetyl-glucosaminidase activity occurs in the freely dissolved phase [11]. This distribution suggests that phosphorus release may occur throughout the water column rather than being concentrated on particles [11].

The proportion of enzymes in the dissolved phase can show extreme variability, with studies finding 0-100% of both α- and β-glucosidase in the dissolved phase within 24-hour periods [12]. Consistently high proportions of all three examined enzymes (α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, and aminopeptidase) were found in the dissolved phase on seasonal scales [12].

Depth-Related Variations

Extracellular enzyme activities typically exhibit weak negative dependency with depth [12]. Activities are generally highest in surface waters where organic matter inputs from phytoplankton production and terrestrial sources are most abundant, gradually decreasing with depth due to reduced substrate availability and microbial biomass.

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Activity Assessment

Sampling Methodology

Collection Protocol:

- Frequency: Sample up to three times per week to capture short-term variability [11].

- Timing: Collect between 08:00 and 09:00 local time to minimize diurnal variation effects [11].

- Location: Sample from surface waters (depth <0.5 m) using clean collection vessels [11].

- Replication: Collect two independent surface water samples on each date [11].

Sample Processing:

- Transport: Transport samples to laboratory at 15-20°C within 30 minutes of collection [11].

- Filtration: Process samples through sequential filtration:

- Bulk seawater: Unfiltered sample

- <2.7 μm fraction: Filtrate through GF/D filters

- <0.2 μm fraction: Filtrate through polyethersulfone syringe filters [11]

- Preservation: Freeze subsamples (-20°C) for subsequent nutrient analysis [11].

Fluorometric Enzyme Assays

Reaction Setup:

- Platform: Conduct assays in black 96-well microplates to minimize light scattering [11].

- Temperature: Run assays at 20°C to simulate environmental conditions [11].

- Duration: Incubate for 1.5 hours, ensuring fluorescence increase remains linear [11].

- Controls: Include appropriate controls:

- Sample blanks: 200 μL sample + 50 μL DI water

- Substrate blanks: 200 μL filtered, autoclaved seawater + 50 μL substrate solution [11]

Reaction Mixture:

- Add 50 μL substrate solution to 200 μL sample to initiate reaction [11].

- Include standards (10 μM 4-methyl-umbelliferone or 10 μM 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin) for fluorescence quantification and quenching correction [11].

- Gently tap microplates to mix solutions before reading [11].

Measurement Parameters:

- Read fluorescence at time zero and at 0.5-hour intervals [11].

- Use excitation/emission wavelengths of 360 nm/460 nm [11].

- Calculate enzyme activities based on product standard curves after accounting for quenching [11].

Table 2: Standardized Enzyme Assay Conditions

| Enzyme | Function | Substrate | Final Substrate Concentration | Fluorophore |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | Hydrolyzes phosphate monoesters | 4-MUB-phosphate | 200 μmol Lâ»Â¹ | Methylumbelliferone (MUB) |

| β-glucosidase (BG) | Releases glucose from polysaccharides | 4-MUB-β-d-glucopyranoside | 40 μmol Lâ»Â¹ | Methylumbelliferone (MUB) |

| Leucine Aminopeptidase (LAP) | Hydrolyzes polypeptides | l-leucine-AMC | 80 μmol Lâ»Â¹ | 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) |

| N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (NAG) | Releases N-acetyl-glucosamine from chitin | 4-MUB-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide | 80 μmol Lâ»Â¹ | Methylumbelliferone (MUB) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Activity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates | 4-MUB-phosphate, 4-MUB-β-d-glucopyranoside, l-leucine-AMC, 4-MUB-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide [11] | Enzyme activity measurement through fluorescent product generation |

| Filtration Materials | 2.7 μm GF/D filters, 0.2 μm polyethersulfone syringe filters [11] | Size fractionation of enzyme activities (particulate vs. dissolved) |

| Detection Instrumentation | Microplate reader (e.g., BioTek Synergy 4) [11] | Fluorometric measurement with 360 nm excitation/460 nm emission |

| Reference Standards | 4-methyl-umbelliferone (MUB), 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) [11] | Quantification of reaction products and correction for fluorescence quenching |

| Sample Containers | Acid-washed polypropylene bottles, pre-rinsed scintillation vials [11] | Prevention of sample contamination during collection and processing |

| (S)-3-hydroxylauroyl-CoA | (S)-3-Hydroxylauroyl-CoA|High Purity | (S)-3-Hydroxylauroyl-CoA is a key intermediate for studying mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. This product is for research use only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

| trans-tetradec-11-enoyl-CoA | trans-tetradec-11-enoyl-CoA Research Chemical | High-purity trans-tetradec-11-enoyl-CoA for research into fatty acid elongation and metabolism. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Integrated Workflow for Spatiotemporal Enzyme Analysis

Data Interpretation and Integration with Metagenomic Analysis

Connecting Enzyme Activities to Microbial Community Dynamics

The spatial and temporal dynamics of extracellular enzymes provide crucial functional insights that complement metagenomic analyses of microbial community structure. Integrating these datasets enables researchers to:

- Link functional capacity with expression: Connect identified enzyme-coding genes in metagenomes with actual enzyme activities measured across temporal and spatial gradients [11].

- Identify key responding taxa: Correlate specific patterns of enzyme activity with shifts in microbial community composition from metagenomic data [11].

- Uncover regulatory mechanisms: Distinguish between changes in microbial abundance versus changes in per-cell enzyme production in response to environmental triggers [11].

Methodological Considerations

- Potential activity measurements: Note that standardized assays with artificial substrates measure potential enzyme activities rather than in situ rates, reflecting enzyme concentrations more than immediate environmental function [11].

- Substrate specificity limitations: Fluorogenic substrate analogs may not fully capture the diversity of natural substrates, potentially overlooking activities toward complex natural polymers [11].

- Integration challenges: Spatial and temporal mismatches between enzyme activity measurements (instantaneous) and metagenomic samples (snapshot in time) require careful experimental design to enable meaningful correlation analyses.

Linking Enzyme Profiles to Biogeochemical Cycling (Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus)

Within marine ecosystems, microbial extracellular enzymes initiate the critical first step in the biogeochemical cycling of organic matter by hydrolyzing complex macromolecules into smaller, bioavailable substrates [1]. These enzymes are fundamental to the microbial loop, responsible for transforming an estimated 50% of surface water primary production [1]. In the context of metagenomic analysis of coastal waters, linking specific enzyme profiles to their biogeochemical functions provides a mechanistic understanding of organic matter processing. This application note details standardized protocols for measuring extracellular enzyme activity (EEA) and connecting these profiles to carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) cycling, enabling researchers to decipher the functional state of microbial communities.

Key Enzymes in Biogeochemical Cycling

The measurement of targeted enzyme activities provides a functional readout of microbial nutrient demands and their role in elemental cycling. The table below summarizes the key enzymes involved in the major biogeochemical pathways.

Table 1: Key Microbial Extracellular Enzymes and Their Biogeochemical Functions

| Element Cycle | Enzyme | Primary Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | β-Glucosidase | Cleaves cellobiose to glucose [14] | Key step in cellulose degradation [1] |

| Phenol Oxidase (PHO) | Degrades recalcitrant aromatic compounds & lignin [14] | Regulates carbon storage via the "enzymic latch" mechanism [14] | |

| Nitrogen | Protease/Peptidase | Degrades proteins into amino acids [1] | Makes organic nitrogen bioavailable |

| Chitinase | Hydrolyzes chitin (N-acetylglucosamine polymer) [1] | Accesses nitrogen stored in fungal cell walls & exoskeletons | |

| Phosphorus | Phosphatase (e.g., PhoD) | Liberates inorganic phosphate from organic esters [14] [15] | Indicates phosphorus limitation; critical for P bioavailability [14] |

Experimental Protocols

Seawater Sampling and Fractionation

Objective: To collect and process water samples for the separation of dissolved and cell-associated enzyme fractions. Materials:

- Submersible pump or Niskin bottles

- Prefilters (20-μm pore size, Millipore)

- Polycarbonate membranes (0.22-μm pore size, Millipore)

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) system with 5000-Dalton membranes (Spectrum Laboratories)

- Syringe filters (0.22-μm polypropylene, Millipore)

Procedure:

- Collection: Collect surface water (e.g., at ~2 m depth) using a submersible pump or Niskin bottles [1].

- Prefiltration: Pass ~10 L of seawater through a 20-μm filter to remove large particles and organisms [1].

- Concentration: Concentrate the prefiltered seawater from ~10 L to 50 mL using a TFF system. Complete the process within 2 hours to preserve enzyme integrity [1].

- Fractionation: To separate dissolved from cell-associated enzymes, gently filter 25 mL of the concentrated sample through a 0.22-μm syringe filter.

- The filtrate contains dissolved enzymes.

- The retentate on the filter contains cell-associated enzymes.

- Storage: Store samples for EEA measurement at 4°C and begin assays within 1 hour. For DNA analysis, preserve filters in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [1].

Measuring Extracellular Enzyme Activity (EEA)

Objective: To quantify the potential hydrolysis rates of various organic substrates using fluorogenic or chromogenic analogs. Materials:

- Substrate analogs: 4-Methylumbelliferyl (MUF)- or 4-Nitrophenyl (PNP)- labeled compounds (e.g., MUF-phosphate, PNP-β-D-glucoside, L-Leucine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin)

- Incubation thermostat

- Microplate reader or spectrophotometer

- Buffers (e.g., TRIS, pH ~8 for seawater)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare saturating concentrations of substrate analogs in an appropriate buffer. Using high substrate concentrations ensures the measurement of potential enzyme activity rather than in situ rates [1].

- Assay Setup: Combine sample (either dissolved or total fraction) with substrate solution in a microplate or test tube. Include controls with killed samples (e.g., addition of trichloroacetic acid) [1].

- Incubation: Incubate assays at in situ temperature (e.g., 25°C) or at elevated temperatures (e.g., 35°C) to test the effect of warming [1].

- Measurement:

- For fluorogenic substrates (MUF, AMC), measure fluorescence over time (e.g., excitation 365 nm, emission 455 nm).

- For chromogenic substrates (PNP), measure absorbance (e.g., 410 nm for p-nitrophenol).

- Calculation: Calculate hydrolysis rates from the linear increase in fluorescence or absorbance over time, using standard curves for the fluorescent or chromogenic product (e.g., MUF or p-nitrophenol). Rates are typically expressed as nmol Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹.

Metagenomic Analysis of Enzyme-Producing Taxa

Objective: To identify microbial clades with the genetic potential to produce target extracellular enzymes. Materials:

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents

- Primers for functional genes (e.g., chiA for chitinase, phoD for phosphatase) and 16S rRNA genes

- High-throughput sequencing platform

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from filters preserving the microbial community.

- Targeted Amplification/Sequencing: Amplify and sequence either:

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process sequences (quality filtering, OTU/ASV picking).

- Assign taxonomy using reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes).

- Identify known enzyme-producing clades (e.g., Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes, Chloroflexi, Roseobacter, Alteromonas, and Pseudoalteromonas) in your dataset [1].

- Integration: Statistically correlate the abundance of specific taxonomic groups or functional genes with measured EEA patterns to link genetic potential to ecosystem function.

Data Integration and Visualization

Integrating enzyme activity data with microbial community and environmental parameters reveals the functional state of the ecosystem. The following workflow diagram outlines the complete experimental pipeline from sampling to data integration.

Conceptual Framework for Data Interpretation

The integrated data can be interpreted through the framework of ecoenzymatic stoichiometry, which links extracellular enzyme activities to microbial resource allocation and nutrient limitation [14]. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between environmental conditions, microbial community response, and the resulting biogeochemical outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EEA Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates (e.g., MUF-/AMC-labeled) [1] | Quantifying hydrolysis rates of specific polymers (e.g., MUF-phosphate for phosphatase). | High sensitivity; allows measurement of low activity in dilute seawaters. |

| Chromogenic Substrates (e.g., PNP-labeled) | Alternative for activity measurement via absorbance. | Less sensitive than fluorogenic assays but widely used. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System [1] | Concentrating dilute extracellular enzymes from large water volumes (>10 L). | 5000-Dalton membranes; gentle on enzyme integrity. |

| Polycarbonate Membranes (0.22 μm) [1] | Fractionating cell-associated vs. dissolved enzymes; collecting biomass for DNA. | Low protein binding; sterile. |

| Primers for Functional Genes (e.g., phoD, chiA) [15] | Profiling microbial communities with genetic potential for enzyme production. | Targets genes encoding specific extracellular enzymes. |

| Dihydrozeatin riboside | Dihydrozeatin riboside, CAS:64070-21-9, MF:C15H23N5O5, MW:353.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Aza-2'-deoxyuridine | 6-Aza-2'-deoxyuridine |

This application note provides a standardized framework for linking microbial enzyme profiles to biogeochemical cycling in coastal waters. The detailed protocols for sample processing, activity measurements, and integrated metagenomic analysis empower researchers to move beyond correlative studies toward a mechanistic, function-based understanding of marine ecosystems. Applying these methods allows for the assessment of how environmental changes, such as nutrient inputs and warming, affect the fundamental microbial processes that drive carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus transformations.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on the metagenomic analysis of extracellular enzymes in coastal waters, this application note addresses a fundamental aspect: identifying the dominant microbial taxa responsible for producing these crucial biocatalysts. In aquatic ecosystems, the initial step of organic matter degradation is primarily mediated by extracellular enzymes secreted by bacteria. Understanding the phylogenetic identity of these key enzyme producers is essential for deciphering microbial community function, ecological niche partitioning, and biogeochemical cycling in coastal environments. This document synthesizes recent research findings to delineate the principal enzyme-producing phyla, quantify their contributions, and provide standardized protocols for their study, serving as a resource for researchers and industrial applications in biotechnology and drug development.

Empirical studies from diverse coastal environments, including mudflats, seawater, and marine sediments, consistently identify three bacterial phyla as the dominant producers of industrial extracellular enzymes: Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes [17] [18] [19]. The distribution and enzymatic strengths of these phyla are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Dominant Enzyme-Producing Phyla in Coastal Marine Environments

| Phylum | Relative Abundance & Prevalence | Principal Enzyme Classes Produced | Notable Genera and Their Enzymatic Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria | Often the most abundant phylum; frequently dominates cultured isolates and metagenomic sequences [17] [20]. | Peptidases, lipases, amylases [17] [21]. | Vibrio spp. (high lipase, amylase, protease) [17]; Pseudomonas, Shewanella (proteases, lipases) [17] [18]; Bacillus (proteases, amylases) [18]. |

| Firmicutes | Highly prevalent in culture-dependent studies from sediments and marine organisms [17] [22] [18]. | Proteases, amylases, phytases [22] [18]. | Bacillus spp. (dominant protease-producers) [18]; Solibacillus, Chryseomicrobium (amylase, lipase, protease) [17]. |

| Bacteroidetes | Major contributor in metagenomic studies; key in polysaccharide degradation [21] [20] [23]. | Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes), including those targeting laminarin, cellulose, and other complex polysaccharides [21] [23]. | Bacteroides, Alistipes, Prevotella (increased in specific metabolic niches) [24]; Tenacibaculum (amylase, lipase, protease) [17]. |

The quantitative output of these taxa is significant. For instance, one study screening 163 marine bacterial isolates found that 88.3% produced lipase, 68.7% produced amylase, and 68.7% produced protease [17] [19]. Furthermore, genetic analysis reveals that the gene pool for organic matter degradation is partitioned among these phyla: Bacteroidota are primary contributors to secretory CAZymes, while Gammaproteobacteria contribute more to secretory peptidases, and Alphaproteobacteria to specific transporters like the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters [21].

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Characterization

A comprehensive understanding of enzyme-producing taxa requires integrating both culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. The following protocols detail standardized approaches for these analyses.

Protocol 1: Culture-Dependent Screening of Hydrolytic Enzyme-Producing Bacteria

This protocol is designed for the isolation and initial functional screening of culturable enzyme-producing bacteria from coastal sediment and water samples [17] [18].

Materials and Reagents

- Marine Agar 2216 & Marine Broth 2216: For general cultivation and growth of marine bacteria [17].

- Screening Agar Plates: Base agar prepared with artificial seawater, supplemented with specific substrates:

- Protease Screening: Add 1% casein and 2% gelatin. Protease activity is indicated by a clear halo zone around colonies [18].

- Amylase Screening: Add 1% soluble starch. Detect activity by flooding plates with iodine solution; a clear zone indicates starch hydrolysis [17].

- Lipase Screening: Use Spirit Blue Agar with lipid sources. Hydrolysis is indicated by a halo zone [17].

- Artificial Seawater: Synthetic sea salt dissolved at 3% (w/v) concentration [18].

- DNA Extraction Kit: e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit for subsequent molecular identification [17].

Procedure

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect coastal mud or water samples. Serially dilute samples (e.g., to 10â»â¶) using sterile artificial seawater [18].

- Plating and Incubation: Spread 100 µL of each dilution onto the specialized screening agar plates. Incubate at temperatures relevant to the sample environment (e.g., 20°C or 35°C) until visible hydrolytic zones form [17] [18].

- Isolation and Purification: Select colonies surrounded by a hydrolytic zone and repeatedly streak them on fresh screening medium at least three times to obtain pure cultures [18].

- Enzyme Activity Quantification: Measure the hydrolytic zone diameter (in mm) and assign a score (e.g., 0: no zone; 3: zone ≥21 mm) to semi-quantify enzyme production strength [17].

- Molecular Identification:

- Extract genomic DNA from pure cultures.

- Amplify the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers (e.g., 27F: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 1492R: 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTTC-3′) via colony PCR [17] [18].

- Sequence the amplicons and identify isolates by comparing sequences with databases like GenBank using the BLAST algorithm or the EzTaxon server [17].

Protocol 2: Culture-Independent Metagenomic Analysis of Enzyme Pathways

This protocol outlines the steps for assessing the functional potential of microbial communities via metagenomic sequencing, bypassing cultural biases [21] [20].

Materials and Reagents

- DNA Extraction Buffers: Lysis buffer containing Tris, EDTA, NaCl, and CTAB for efficient cell disruption from environmental samples [20].

- Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol: For purification of metagenomic DNA.

- Illumina Sequencing Platform: e.g., HiSeq 2500 for high-throughput sequencing [20].

- Bioinformatics Software:

- SOAPnuke/MEGAHIT/IDBA: For sequence quality control and de novo assembly [20].

- MetaGeneMark: For predicting open reading frames (ORFs) from assembled contigs [20].

- DIAMOND/KEGG/CAZy: Tools and databases for functional annotation of predicted genes against KEGG, CAZy, and other specialized databases [21] [20].

Procedure

- Metagenomic DNA Extraction: From 10g of humus or sediment, extract DNA using a combination of chemical lysis (SDS, CTAB), enzymatic treatment (proteinase K), and organic purification (phenol-chloroform). Precipitate DNA with isopropanol, wash, and resuspend [20].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare a paired-end sequencing library from the high-quality DNA and sequence on an Illumina platform to generate 150 bp reads [20].

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: Filter raw reads to remove adapters and low-quality sequences.

- Assembly: Assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT with a range of k-mer sizes [20].

- Gene Prediction and Annotation: Predict ORFs from contigs. Functionally annotate the ORFs by alignment against public databases (KEGG, CAZy) to identify genes encoding extracellular enzymes (e.g., peptidases, CAZymes) and transporters (e.g., TonB-dependent transporters) [21] [20].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to contigs or ORFs by comparing them with reference databases to link enzymatic functions with phylogenetic identity [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Studying Enzyme-Producing Microbes

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Marine Agar/Broth 2216 | Cultivation of heterotrophic marine bacteria. | Standardized nutrient medium mimicking seawater. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from bacterial pure cultures. | Silica-membrane technology for purity and yield. |

| OMEGA Soil DNA Kit | Extraction of metagenomic DNA from complex environmental samples like sediment. | Effective for difficult-to-lyse cells and inhibitor removal. |

| MyTaq Mix | PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes for phylogenetic identification. | Pre-mixed, optimized for robustness with complex templates. |

| Spirit Blue Agar / Starch Agar | Selective screening for lipolytic and amylolytic bacterial isolates. | Contains specific substrates for visual detection of enzyme activity. |

| 8-(1,1-Dimethylallyl)genistein | 8-(1,1-Dimethylallyl)genistein, MF:C20H18O5, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Threo-guaiacylglycerol | Threo-guaiacylglycerol, MF:C10H14O5, MW:214.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow for Analysis of Enzyme-Producing Taxa

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between the two primary methodological approaches described in the protocols.

In coastal aquatic ecosystems, the microbial processing of organic matter is a fundamental driver of biogeochemical cycles. This process is initiated by extracellular enzymes produced by heterotrophic microbial communities, which hydrolyze complex organic polymers into smaller, assimilable molecules [21] [25]. The expression and activity of these enzymes are not static; they are dynamically regulated by key environmental drivers, including nutrient availability, temperature, and dissolved oxygen concentrations. Understanding these relationships is critical for predicting organic matter turnover and is a core component of metagenomic analyses of coastal waters. This Application Note details the experimental protocols for quantifying these relationships and their implications for microbial ecology and biogeochemical modeling.

Key Environmental Drivers and Quantitative Effects

The activity of microbial extracellular enzymes exhibits distinct and quantifiable responses to changes in the ambient environment. The table below summarizes the documented effects of specific environmental factors on key enzyme activities, serving as a reference for interpreting experimental results.

Table 1: Environmental Drivers of Extracellular Enzyme Activity (EEA) in Aquatic Systems

| Environmental Driver | Measured Effect on Enzyme Activity | Specific Enzymes / Systems Affected | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increase from 25°C to 35°C raised hydrolysis rates. | Polysaccharide hydrolases (e.g., for CMC, chitin, alginic acid) and protease. | Northern Chinese Marginal Seas [25] |

| Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) | Positive association with geographic distribution of EEA; higher concentrations correlated with higher inshore enzyme activity. | Phosphatase, β-glucosidase, protease. | Northern Chinese Marginal Seas; Neuse and Tar-Pamlico Rivers [26] [25] |

| Nutrient Availability | Microbial community nutrient demands influence enzymatic profiles; phosphorous limitation can stimulate phosphatase activity. | Phosphatase, peptidases, polysaccharide hydrolases. | Neuse and Tar-Pamlico Rivers [26] |

| Organic Matter Substrate Type | All tested substrates (polymers and oligomers) were hydrolyzed, but at different rates. Hydrolysis not strictly limited by molecule size. | Enzymes targeting CMC, chitin, alginic acid, casein, and their oligomers. | Northern Chinese Marginal Seas [25] |

| Salinity & Hydrology | Considerable spatiotemporal variability in EEA; hurricane-induced discharge led to persistent DOC maxima and stimulated bacterial production. | β-glucosidase, leucine aminopeptidase, phosphatase. | Neuse and Tar-Pamlico Rivers [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Field Sampling and Metagenomic Analysis of Enzyme-Transporter Coupling

This protocol is designed to investigate the genetic potential for organic matter degradation in coastal bacterial communities, as revealed by metagenomic sequencing.

1. Sample Collection:

- Collect coastal water samples over a time-series (e.g., 22-day period) from multiple depths to capture temporal and spatial variability [21].

- Filter water samples through appropriate pore-size filters (e.g., 0.22 μm) to capture microbial biomass onto the filter for DNA extraction.

2. DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Sequencing:

- Perform genomic DNA extraction from the filters using a commercial soil or water DNA extraction kit.

- Prepare metagenomic libraries and sequence using an Illumina or similar high-throughput sequencing platform.

3. Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Assembly and Binning: Process raw sequencing reads to assemble contigs and bin them into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). A target of 163 MAGs, as in the cited study, provides robust data for correlation analysis [21].

- Gene Annotation: Annotate genes in the assembled contigs and MAGs against functional databases to identify key genes:

- Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes): Use dbCAN2 or similar tools.

- Peptidases: Use MEROPS database.

- Transporters: Identify genes for TonB-dependent transporters (TBDTs) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters.

- Statistical Correlation: At both the community-wide and MAG-specific levels, calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson's) between the abundance of extracellular enzyme genes (CAZymes, peptidases) and transporter genes (TBDTs, ABC transporters). This reveals potential coregulation and functional linkages [21].

Protocol 2: Measuring In-situ Extracellular Enzyme Activity (EEA)

This protocol measures the actual hydrolysis rates of organic matter, providing a ground-truthed measure of microbial functional response.

1. Water Sampling and Pre-processing:

- Collect surface water (e.g., from 2 m depth) using a submersible pump or Niskin bottles [26] [25].

- Pre-filter water through a 20-μm mesh to remove large particles and organisms.

- For total EEA, use the pre-filtered water directly. For dissolved EEA, further filter a portion through a 0.22-μm syringe filter to remove cells while retaining dissolved enzymes [25].

2. Enzyme Activity Assay via Substrate Hydrolysis:

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare a panel of fluorogenic or chromogenic substrate proxies. Common substrates include:

- 4-Methylumbelliferyl (MUF)- or 4-Nitrophenyl (PNP)- labeled derivatives (e.g., MUF-β-glucoside for β-glucosidase, MUF-phosphate for phosphatase, L-leucine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin for protease) [26].

- Fluoresceinamine-labeled polysaccharides (e.g., carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), chitin, alginic acid) and proteins (e.g., casein) to measure hydrolysis of real polymers [25].

- Incubation:

- Add substrates to seawater samples (total and dissolved) and incubate in the dark.

- Conduct assays at in-situ temperature (e.g., 25°C) and at a higher temperature (e.g., 35°C) to assess temperature sensitivity [25].

- Run controls with autoclaved or filtered sample to account for non-enzymatic hydrolysis.

- Measurement:

- For MUF/PNP substrates, measure fluorescence/absorbance at regular intervals using a plate reader. The increase in signal is proportional to hydrolysis rate.

- For polymer substrates, hydrolysis can be quantified by the increase in fluorescence as the labeled fragment is released, or by size-exclusion chromatography to detect the breakdown products [25].

3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate hydrolysis rates (nmol Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ or μg Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹) from the linear increase of product over time.

- Correlate EEA rates with concurrently measured physicochemical parameters (temperature, DOC, nutrient concentrations, dissolved oxygen) to identify key environmental drivers [26] [25].

Visualization of Environmental-Microbial Interactions

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mechanistic relationships between environmental drivers, microbial genetic regulation, and the resulting biogeochemical outcomes in coastal waters.

Environmental Drivers Shape Microbial Enzyme Expression. This workflow diagrams how abiotic factors influence microbial genomics and metabolism, leading to biogeochemical outcomes like organic matter remineralization. Key interactions include the coupling between enzyme and transporter gene expression, a critical link identified via metagenomics [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents required for the experimental protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EEA and Metagenomic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrate Proxies (e.g., MUF/AMC derivatives) | Quantifying hydrolysis rates of specific enzyme classes (e.g., glucosidases, phosphatases, peptidases) [26]. | Select substrates relevant to the organic matter pool (e.g., algal polysaccharides). Include a negative control. |

| Labeled Biopolymers (e.g., Fluoresceinamine-labeled CMC, Chitin) | Measuring hydrolysis rates of ecologically relevant polymers, not just proxies [25]. | Allows comparison of hydrolysis rates between polymers and their oligomers. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System | Concentrating extracellular enzymes from large water volumes (e.g., 10L to 50mL) to enable detection of activity on natural polymers [25]. | Use membranes with appropriate molecular weight cut-offs (e.g., 5 kDa). |

| Polycarbonate Membranes (0.22 μm) | Concentrating microbial biomass from water samples for subsequent DNA extraction and metagenomic analysis [21]. | Ensure sterile and nuclease-free conditions for DNA work. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolating high-quality metagenomic DNA from environmental filters. | Optimized for environmental samples (soil, water) to overcome inhibitors. |

| Functional Annotation Databases (dbCAN2, MEROPS) | Bioinformatic annotation of CAZyme, peptidase, and transporter genes from metagenomic data [21]. | Use curated databases and set appropriate E-value cutoffs for homology searches. |

| 2,3-dihydroxy-2,3-dihydrobenzoyl-CoA | 2,3-dihydroxy-2,3-dihydrobenzoyl-CoA, MF:C28H42N7O19P3S, MW:905.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Butyl diphenyl phosphate | Butyl diphenyl phosphate, CAS:2752-95-6, MF:C16H19O4P, MW:306.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The expression and activity of microbial extracellular enzymes are powerfully shaped by the interplay of nutrients, temperature, and oxygen. Metagenomic approaches reveal the genetic potential and coupling of degradation pathways, while direct activity measurements capture the realized functional response of the community to environmental gradients. The protocols and data presented here provide a framework for researchers to systematically investigate these relationships, ultimately leading to a more predictive understanding of organic matter cycling in dynamic coastal waters.

Advanced Metagenomic Workflows: From Sampling to Functional Annotation

Sample Collection Strategies Across Coastal Gradients and Depths

The reliability of metagenomic data in coastal enzyme research is fundamentally constrained by the initial sample collection strategy. The dynamic interface of coastal environments, characterized by steep physical, chemical, and biological gradients, demands meticulous planning and execution of sampling protocols to ensure representative and uncontaminated samples. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for designing and implementing sample collection strategies across coastal gradients and depths, specifically tailored for subsequent metagenomic analysis of extracellular enzymes. The objective is to equip researchers with standardized methodologies that enhance data comparability, minimize technical artifacts, and support robust ecological inferences regarding microbial community function in coastal waters.

Understanding the Sampling Environment

Coastal regions are transition zones where environmental parameters shift dramatically over small spatial and temporal scales. Recognizing these gradients is the first step in designing a statistically sound sampling plan.

Key Gradients and Their Implications

- Salinity Gradients: Salinity acts as a critical environmental filter on microbial communities [27] [28]. Cross-shore salinity gradients, often driven by riverine freshwater input, create distinct niches that host phylogenetically and functionally diverse microbial populations. Sampling must capture this variation to avoid biased functional profiles.

- Nutrient and Chemical Gradients: Land-based sources of pollution, including dissolved nitrogen, phosphorus, and silicate, can create strong water quality gradients that influence microbial metabolism and extracellular enzyme production [29]. As evidenced in Aua Reef, American Samoa, these gradients are measurable and can correlate with benthic community structure.

- Particulate and Organic Matter Gradients: The concentration of small microplastics (SMPs) and other particulates often decreases from the coastline toward the open ocean [30]. Similarly, the quality and quantity of organic matter, which drives extracellular enzyme activity (EEA), vary significantly with distance from shore and depth [31] [32].

Temporal Dynamics

Extracellular enzyme activities in coastal environments are highly dynamic. A multi-year time-series study in Southern California found that 34–48% of the variation in enzyme activity occurred at timescales of less than 30 days, influenced by short-term events like phytoplankton blooms, upwelling, and rainfall [33]. Sampling designs must therefore account for diel, tidal, and seasonal cycles to accurately capture the metabolic potential of the microbial community.

Sampling Strategies and Technologies

The choice of sampling technology is paramount for preserving the integrity of samples intended for sophisticated metagenomic analysis. The selection depends on the target sample type (water, sediment), depth, and required preservation state.

Water Sampling Techniques and Equipment

Table 1: Comparison of Seawater Sampling Technologies for Metagenomic Studies

| Technology/Sampler | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Use Cases for Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niskin/Rosette Sampler [34] | Penetration form; cylindrical sampling chambers with end caps triggered at target depth. | Can house multiple chambers (e.g., 12-24); discrete depth sampling; standard for oceanography. | Potential for contamination between strata if valve closure is incomplete. | Collecting large-volume, discrete depth samples from the water column in coastal and offshore regions. |

| Gulper Sampler [34] | Negative pressure, plunger-based; spring-driven piston rapidly draws in water. | Rapid collection; adaptable for AUVs/ROVs; minimizes sample mixing. | Limited sample volume per deployment. | High-resolution spatial sampling from autonomous platforms; targeted sampling of transient features. |

| Gas-Tight Water Samplers [35] | Displacement-based collection with sophisticated sealing. | Eliminates gas exchange; preserves dissolved gases and volatile organics. | Complex operation; higher cost. | Studying anaerobic microbial processes or when preserving in-situ gas concentrations is critical. |

| Vacuum Chamber Samplers [34] | Pre-evacuated chambers open at depth; water is drawn in by pressure difference. | Simple mechanism. | Fixed, often small sample volume; volume is uncontrollable. | Small-volume water sampling for specific biomarker analysis. |

Sediment Sampling Techniques and Equipment

Sediment sampling requires specialized coring equipment to preserve the sediment-water interface and stratigraphic integrity, which is crucial for understanding depth-related microbial processes.

Table 2: Comparison of Sediment Coring Technologies for Metagenomic Studies

| Technology/Corer | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Use Cases for Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Corer (MUC) [35] | Gravity-assisted descent with hydraulic dampening. | Preserves the sediment-water interface; collects multiple, simultaneous, minimally disturbed cores. | Limited penetration depth (typically up to 60 cm). | Studying surface sediment processes, bioturbation, and the most recent depositional layer. |

| Giant Box Corer (GBC) [35] | Large-scale sampling platform with spring-loaded sealing. | Collects a large, undisturbed sediment volume (e.g., 50cm x 50cm surface area). | Significant disturbance during deployment and recovery; not suitable for fine-scale depth resolution. | When large sample volumes are needed for multiple analytical procedures (e.g., coupled metagenomics, enzyme assays, and chemistry). |

| Gravity Corer [35] | Precisely calculated weight for controlled penetration. | Achieves greater penetration depths; high recovery rates (90-98%). | Can compress sediment layers upon impact. | Sampling deeper sediment horizons to investigate historical microbial communities and paleo-metagenomics. |

Sampling Across a Coastal Gradient: A Practical Workflow

The following workflow diagram outlines a strategic approach to sampling across a coastal gradient, from inland waters to the outer shelf.

Strategic Coastal Sampling Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cross-Shore Water Column Profiling and Sampling

Application: Characterizing microbial community and extracellular enzyme potential across a salinity/nutrient gradient.

Materials:

- Research vessel or small boat

- CTD rosette system equipped with Niskin bottles (e.g., 5L or 10L)

- GPS unit

- Portable filtration rig

- Peristaltic pump and silicone tubing

- Sterile filtration units (0.22 µm pore size, polyethersulfone membrane)

- Cryovials for nucleic acid preservation

- Liquid nitrogen or -80°C dry shipper

Procedure:

- Transect Establishment: Based on remote sensing data of sea surface salinity [27] or known river plume pathways, establish 3-5 transect lines perpendicular to the coast, from estuarine or river-influenced waters to the outer shelf.

- Station Selection: Mark stations along each transect (e.g., at 1 km, 5 km, 10 km, and 20 km from shore) to capture the gradient.

- In-situ Profiling:

- At each station, lower the CTD rosette to within 5-10 meters of the seabed.

- Record continuous profiles of conductivity (salinity), temperature, depth, chlorophyll-a fluorescence, dissolved oxygen, and pH [29].

- Use this real-time data to identify specific sampling depths (e.g., surface, chlorophyll maximum, bottom waters).

- Discrete Water Sampling:

- Trigger Niskin bottles at the predetermined depths.

- Upon recovery, immediately transfer water from the Niskin bottles into pre-cleaned containers in a dedicated, contamination-controlled van or clean area on deck.

- Filtration for Metagenomics:

- For metagenomic analysis, process samples immediately.

- Filter a known volume of seawater (typically 1-4 L, depending on particulate load) through a 0.22 µm sterile filter using a peristaltic pump to capture microbial biomass [1].

- Using sterile forceps, carefully fold the filter and place it into a cryovial.

- Flash-freeze the filter in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until nucleic acid extraction.

Protocol 2: Multi-depth Sediment Coring and Sub-sampling

Application: Investigating the vertical stratification of microbial communities and extracellular enzymes in seafloor sediments.

Materials:

- Multiple Corer (MUC) or Gravity Corer, depending on depth requirement

- Polycarbonate or acrylic core tubes

- Core processing station (clean, level area)

- Nitrogen glove bag (for anoxic samples)

- Sterile syringes with trimmed ends

- Spatulas and scalpels

- Centrifuge tubes or vials for sub-samples

Procedure:

- Core Collection:

- Deploy the MUC/Gravity Corer at the designated station.

- Upon recovery, carefully extract the core tubes, ensuring they remain vertical. Cap the ends to prevent oxidation and disturbance.

- Core Description and Sectioning:

- At the processing station, remove the top cap and carefully note the appearance of the sediment-water interface.

- For metagenomic sub-sampling under anoxic conditions, place the entire core inside a nitrogen-filled glove bag.

- Using a sterile syringe with the end tip cut off, push the plunger in slightly and insert the syringe barrel into the sediment at the desired depth interval (e.g., 0-1 cm, 1-2 cm, 2-5 cm).

- Gently pull the plunger to extract a plug of sediment. Expel the sediment plug into a pre-labeled cryovial.

- Sample Preservation:

- For DNA analysis, immediately freeze the sediment sub-samples in liquid nitrogen and transfer to -80°C for long-term storage.

- Parallel sub-samples should be taken for measuring extracellular enzyme activity, which must be processed fresh or stored under specific conditions as required by the assay protocol [31] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Field Sampling and Preservation

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Filtration Membranes | Polyethersulfone (PES), Sterivex filter units, 0.22 µm pore size. | Sterile filtration of water samples to collect microbial biomass for DNA/RNA extraction. PES is preferred for low nucleic acid binding. |

| Nucleic Acid Preservation | RNAlater, DNA/RNA Shield, LifeGuard Soil Preservation Solution. | Chemically stabilizes nucleic acids immediately upon collection, preventing degradation during transport. Crucial for accurate metagenomic and metatranscriptomic results. |

| Sample Containers | Sterile polypropylene cryovials; Whirl-Pak bags. | Inert, leak-proof containers for storing filters, sediments, and water samples. Must be pre-cleaned and sterilized to prevent contamination. |

| Substrates for Enzyme Assays | 4-Methylumbelliferyl (MUF)-labeled substrates (e.g., MUF-phosphate, MUF-β-D-glucoside); 7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC)-labeled substrates (e.g., L-Leucine-AMC). | Fluorogenic model substrates used to measure potential extracellular enzyme activities (e.g., phosphatase, β-glucosidase, leucine-aminopeptidase) in water and sediment samples [33] [32]. |

| CTD Calibration Solutions | IAPSO Standard Seawater; pH buffer solutions (e.g., TRIS, AMP). | Used for the precise calibration of CTD sensors (conductivity, pH) before and after a research cruise to ensure data accuracy. |

| 2-amino-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)acetic Acid | 2-amino-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)acetic Acid, MF:C9H11NO3, MW:181.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-(6-Bromo-2-benzothiazolyl)benzenamine | 4-(6-Bromo-2-benzothiazolyl)benzenamine, CAS:566169-97-9, MF:C13H9BrN2S, MW:305.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Integration and Downstream Analytical Considerations

Effective sample collection is the foundation for meaningful metagenomic analysis. The relationship between field strategies and lab-based molecular workflows is illustrated below.

From Field Collection to Integrated Analysis

- Metadata is Paramount: Every sample must be linked to a comprehensive set of metadata, including GPS coordinates, depth, time/date of collection, and in-situ measurements (temperature, salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen). This environmental context is essential for interpreting metagenomic data.

- Integrated Analysis: The power of a well-designed sampling strategy is realized when metagenomic data (e.g., relative abundance of glycosyl hydrolase genes) is correlated with direct measurements of extracellular enzyme activity [1] [32] and environmental parameters (e.g., nutrient concentrations, salinity [28]). This integrated approach moves beyond correlation to provide mechanistic insights into the drivers of microbial biogeochemical cycles in coastal waters.

DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Library Preparation for Diverse Communities

Metagenomics has revolutionized the study of microbial communities, enabling researchers to analyze genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples. For research focused on extracellular enzymes in coastal waters, the quality of metagenomic data is profoundly influenced by the initial steps of DNA extraction and library preparation. These protocols must be optimized to effectively lyse diverse cell types, recover DNA from often low-biomass and inhibitor-rich aqueous environments, and construct libraries suitable for revealing functional potential, such as the genes encoding extracellular enzymes. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide these critical processes.

DNA Extraction Method Comparison and Selection

The choice of DNA extraction method significantly impacts DNA yield, purity, and the representative nature of the subsequent metagenomic data. Different kits exhibit varying performance across sample types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Commercial DNA Isolation Kits for Different Sample Types [36]

| Kit Name | Short Name | Key Features | Recommended Sample Type | DNA Yield | Inhibitor Removal | Eukaryotic DNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | PowerFecal | Bead beating, Inhibitor Removal Technology | Water, Sediment, Stool | High | Excellent | Moderate |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | PowerSoil | Bead beating, optimized for humic acid removal | Sediment, Soil | High | Excellent | Low |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Microbiome | Selective host DNA depletion (benzonase) | Host-associated (e.g., digestive tract) | Moderate | Good | Excellent |

| PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit | PureLink | Mechanical & chemical lysis | Water, Sediment | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

Application Note: Depletion of Host and Extracellular DNA

Coastal water samples can contain extracellular DNA (eDNA) from lysed cells, which may not represent the active microbial community. Furthermore, samples like filter-feeder digestive tracts or particle-associated communities introduce high levels of non-target eukaryotic DNA. A method combining selective lysis and endonuclease digestion is highly effective for enriching for intracellular microbial DNA [37].

Protocol: Selective Lysis and Endonuclease Digestion for Water Filters [37]

- Sample Preparation: After filtering a water sample, resuspend the filter material in 1 mL of hypotonic lysis buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0).

- Eukaryotic Cell Lysis: Add a non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.5% Tween-20) and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle agitation to lyse eukaryotic cells without disrupting microbial cells.

- Endonuclease Digestion: Add MgCl₂ to a final concentration of 5 mM and a broad-spectrum endonuclease (e.g., Benzonase). Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes to degrade extracellular DNA (both human and bacterial).

- Microbial Cell Pelletation: Centrifuge the sample at high speed (e.g., 14,000 x g for 10 minutes) to pellet intact microbial cells. Discard the supernatant containing digested DNA.

- DNA Extraction: Proceed with DNA extraction from the microbial cell pellet using a bead-beating kit (e.g., PowerFecal or PowerSoil) to ensure lysis of robust microbial cells.

Metagenomic Library Preparation Protocols

The construction of sequencing libraries is a critical step that influences gene detection and functional analysis.

Comparison of Library Preparation Kits

The choice of library prep kit can affect the number of genes detected and the overall community profile.

Table 2: Comparison of Metagenomic Library Preparation Protocols [38]

| Library Prep Kit | Fragmentation Method | Typical Insert Size | Relative Detected Gene Count | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KH) | Mechanical (e.g., sonication) | ~250 bp | Higher | Robust performance for metagenomic profiling. |

| TruePrep DNA Library Prep Kit V2 (TP) | Enzymatic (Tagmentation) | ~350 bp | Lower | Faster workflow; may have slightly lower gene detection. |

Protocol: Shotgun Metagenomic Library Preparation using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit