Mitigating Genetic Drift in Synthetic Biology: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Control Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, manage, and counteract genetic drift in engineered biological systems.

Mitigating Genetic Drift in Synthetic Biology: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Control Strategies

Abstract

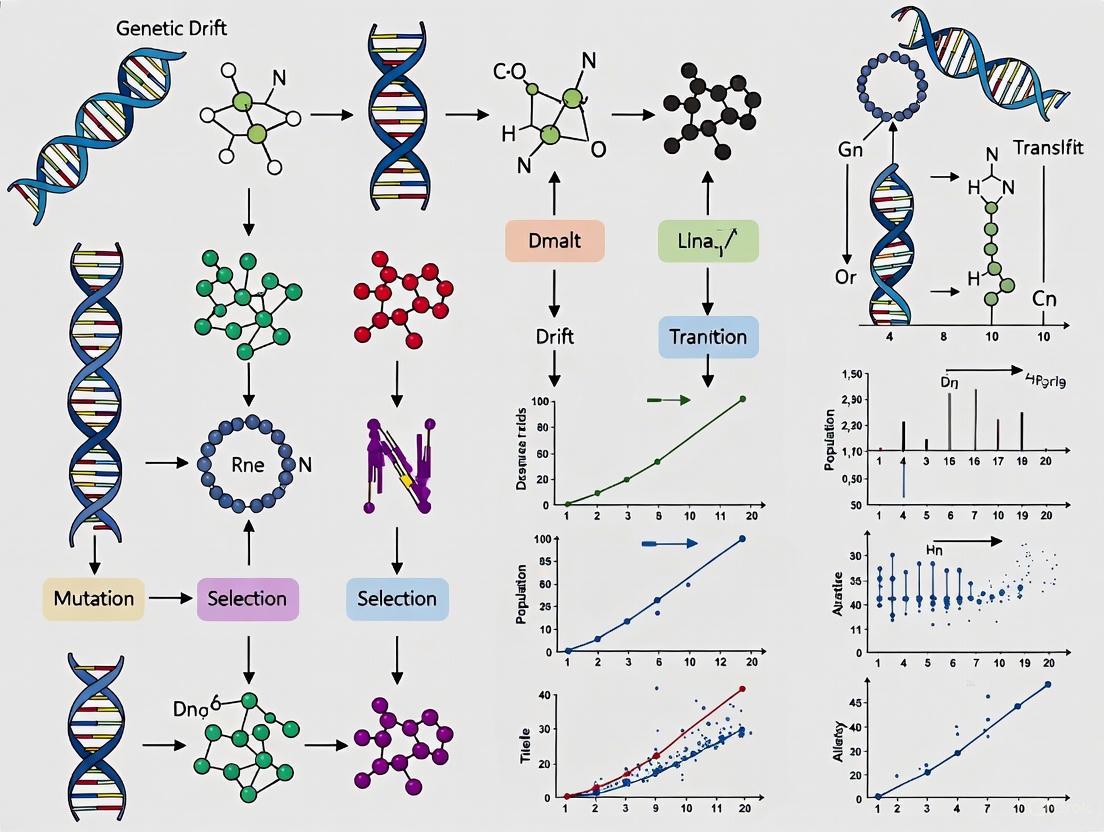

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, manage, and counteract genetic drift in engineered biological systems. Synthesizing the latest research, we explore the fundamental principles and insidious impacts of genetic drift on system stability and therapeutic efficacy. The content details a suite of cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies, from evolutionary algorithms and genotype-preference selection to biosafety-enhanced chassis design, offering practical solutions for robust system optimization. We further present rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of mitigation techniques, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on integrating these strategies into the drug development pipeline to ensure the reliable and safe application of synthetic biology in biomedicine.

Genetic Drift Fundamentals: Understanding the Unseen Threat to Synthetic Biological Systems

What is Genetic Drift?

Genetic drift is a fundamental evolutionary process where allele frequencies within a population change randomly due to sampling error from one generation to the next [1]. Unlike natural selection, which is a directional process favoring adaptive traits, genetic drift is a non-directional, random process that can lead to the fixation or loss of alleles regardless of their selective value [2]. The magnitude of its effect is inversely related to population size, making it a particularly potent force in small, isolated populations such as those found in laboratory colonies, breeding programs, and synthetic biological systems [2] [1].

Key Characteristics and Consequences:

- Driven by Chance: The random fluctuation in allele frequencies is a result of chance events in gamete sampling [1].

- Stronger in Small Populations: The effect of genetic drift is more pronounced in populations with a small effective population size (Nâ‚‘) [2] [1]. The expected variance in allele frequency (p) after one generation is given by Var(p) = pâ‚€qâ‚€/2Nâ‚‘ for diploid organisms [1].

- Leads to Fixation or Loss of Alleles: Over time, drift can cause alleles to reach a frequency of 1.0 (fixation) or 0.0 (loss) [1]. The probability of fixation for a neutral allele is equal to its current frequency [1].

- Reduces Genetic Diversity: By causing the loss of alleles, drift decreases the genetic variation within a population [1].

- Increases Population Subdivision: Isolated populations subjected to drift will become genetically differentiated from one another over time [1].

- Can Overwhelm Selection: In small populations, genetic drift can lead to the fixation of deleterious alleles or the loss of beneficial ones, reducing the efficacy of natural selection [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Genetic Drift in Engineered Organisms

This guide addresses common issues researchers face when genetic drift disrupts experimental systems or production lineages.

| Problem | Primary Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solutions & Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of engineered function (e.g., reporter gene silencing, decreased pathway output) | Fixation of deleterious mutations in synthetic constructs or regulatory elements due to strong genetic drift [2] [3]. | Diminished fluorescent signal, reduced product titers in a subset of cultures, confirmed by sequencing. | 1. Increase population size during culture passages [1].2. Implement periodic selection to maintain functional lineages.3. Use genomic barcoding to track lineage diversity and bottlenecks. |

| Phenotypic divergence between identical starter cultures | Founder effects and bottlenecks during sub-culturing, leading to random fixation of different alleles in parallel lines [2] [3]. | High variance in growth rates, morphology, or output between technical replicates started from the same clonal source. | 1. Standardize culture volume and inoculation density [2].2. Use single-use master cell banks instead of serial passaging [2].3. Perform population genomics to confirm neutral divergence. |

| Unexpected emergence of a novel phenotype | Drift-driven fixation of a spontaneous mutation that was present at a low frequency in the founder population [2]. | A new, stable trait appears in a culture (e.g., antibiotic resistance, altered metabolism) without directed evolution. | 1. Resequence the population to identify the causal mutation.2. Re-constitute the culture from an earlier, cryopreserved stock to confirm it is a new fixation. |

| Reduced fitness and viability in a lab population | Increased genetic load; drift fixes slightly deleterious mutations, leading to inbreeding depression, especially in small colonies [2] [3]. | Decreased growth rate, lower sporulation efficiency, or reduced reproductive output over generations. | 1. Outcrossing (if possible) to introduce genetic variation and mask deleterious alleles [3].2. Expand population size to reduce the strength of drift [1].3. Enforce rotational breeding schemes [2]. |

FAQs on Genetic Drift in Research Settings

Q1: What is the difference between a population bottleneck and a founder effect? Both are forms of genetic drift that cause a sudden reduction in genetic diversity. A bottleneck occurs when a population undergoes a drastic, often temporary, reduction in size (e.g., from a freeze-thaw cycle or biocontainment breach) [1]. A founder effect occurs when a new population is established by a small number of individuals from a larger source population (e.g., initiating a new culture from a single colony) [1]. The northern elephant seal is a classic bottleneck example, while the introduction of Mycosphaerella graminicola to Australia exemplifies a founder effect [2] [1].

Q2: How can I measure genetic drift in my experimental system? Genetic drift can be quantified by tracking changes in neutral genetic markers over generations.

- Direct Method: Use whole-genome sequencing or high-density SNP genotyping of populations across multiple time points. Calculate the variance in allele frequencies at neutral sites over time. The variance is expected to be Var(p) = p₀q₀[1 − (1 − 1/2Nₑ)^t] after t generations [1].

- Indirect Method: Estimate the effective population size (Nâ‚‘), which determines the rate of drift. Nâ‚‘ can be inferred from genomic data by measuring the rate of inbreeding (increase in homozygosity) or the extent of linkage disequilibrium (non-random association of alleles) [1].

Q3: What is the propagule model and how does it relate to genetic drift? The propagule model describes the genetic outcome when new subpopulations are founded by one or a few individuals, creating a severe genetic bottleneck [3]. This leads to new subpopulations having low genetic diversity and being highly genetically differentiated from each other and their source. Immigration can later increase diversity and reduce differentiation. This model is highly relevant to lab workflows involving colony isolation and is supported by genomic studies in dynamic metapopulations like Daphnia magna [3].

Q4: Can genetic drift ever be beneficial in a research or bioproduction context? While typically a complicating factor, drift can occasionally be leveraged. In directed evolution experiments, drift in small populations can randomly fix a beneficial mutation that might otherwise be lost in a larger population due to competition. It can also facilitate the accumulation of non-adaptive mutations that lead to population subdivision, which can be useful for studying speciation or generating diversity for screening [1].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Quantifying Drift Using Barcoded Lineages

This methodology uses neutral genetic barcodes to directly visualize and quantify the impact of drift in a microbial population.

Detailed Methodology:

- Library Construction: Generate a diverse library of isogenic engineered cells, each carrying a unique, neutral DNA barcode integrated into a safe-harbor genomic locus.

- Founder Population: Mix barcoded lineages to create a highly diverse founder population. Use sequencing to confirm the initial equal frequency of barcodes.

- Experimental Passaging: Passage multiple replicate populations from the founder culture for a set number of generations. A key parameter is to vary the population size at each transfer to experimentally manipulate the strength of drift.

- Sample and Sequence: At designated time points, sample biomass from each replicate population. Extract genomic DNA and use PCR to amplify the barcode region for high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the frequency of each barcode in each replicate over time. Calculate summary statistics like Shannon's Diversity Index to measure diversity loss. The variance in barcode frequency across replicates directly measures drift.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Phenotypic Divergence

This protocol assesses the functional consequences of drift by tracking core phenotypes over time.

Detailed Methodology:

- Baseline Characterization: For a clonal population of your engineered organism, establish baseline measurements for key phenotypes (e.g., growth rate, fluorescence intensity, product yield).

- Establish Replicate Lines: Start a large number (e.g., 50-100) of independent replicate cultures from this clonal source.

- Serial Propagation: Propagate each line independently for a pre-determined number of generations, ensuring each transfer involves a controlled, small bottleneck (e.g., 1:1000 dilution).

- Phenotypic Screening: At regular intervals, assay all replicate lines for the key phenotypes.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the variance and distribution of phenotypic values across replicates. An increase in variance over time, without selection, is a hallmark of drift acting on underlying genetic variation. Compare the distribution to the original baseline to identify lines where fixation of mutations may have caused significant divergence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Drift Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cryopreservation Agents (e.g., Glycerol, DMSO) | To create stable master cell banks, archiving population states at specific generations and preventing further drift. | Periodically freezing population samples during a long-term passage experiment to create a "fossil record" [2]. |

| Neutral DNA Barcodes | To tag individual lineages within a population, allowing their frequency to be tracked via sequencing without affecting fitness. | Inserting a unique 20bp random sequence into a neutral genomic location to directly visualize lineage extinction and fixation [2]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | To minimize the introduction of new mutations during PCR for genotyping or barcode library construction. | Amplifying barcode regions for sequencing with minimal error, ensuring accurate frequency counts [4]. |

| Genomic DNA Cleanup Kits | To purify DNA from population samples before sequencing, removing contaminants like salts that can inhibit enzymes. | Cleaning up gDNA extracted from a whole population sample before sending for NGS to ensure high-quality data [4]. |

| Inbred or Isogenic Strains | To provide a uniform genetic background, reducing standing variation and making drift-evolved changes easier to detect. | Starting a drift experiment with a genetically identical clone to ensure any divergence is due to new mutations and drift [2]. |

| Sarafloxacin-d8 | Sarafloxacin-d8, MF:C20H17F2N3O3, MW:393.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (E)-coniferin | (E)-coniferin, MF:C16H22O8, MW:342.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses frequently asked questions and specific issues you might encounter in your research on genetic drift and therapeutic protein production.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: We are observing unexpected and inconsistent drops in therapeutic protein yield in our engineered microbial populations over multiple generations. Could genetic drift be the cause? Yes, genetic drift is a likely culprit. In any finite population, genetic drift causes random fluctuations in allele frequencies. In the context of synthetic biology, this can lead to the loss of engineered genetic constructs—such as plasmids or expression cassettes for your therapeutic protein—from the population over time, especially if these constructs impose any metabolic burden, even a slight one. This non-selective, random loss directly compromises production yield and consistency [5] [6].

FAQ 2: How can we distinguish between a problem caused by genetic drift and one caused by natural selection? The key differentiator is selective advantage. If a drop in yield is due to natural selection, you would expect to see the proliferation of a specific, fitter genetic variant that does not express your protein, or expresses it at a lower cost. In contrast, genetic drift is a random process; the loss of production capability occurs stochastically and is not linked to a specific fitness advantage. Monitoring the genetic diversity of your production strain population, not just the average yield, can help identify the signature of drift [5].

FAQ 3: What are the primary biosafety risks introduced by genetic drift in engineered organisms? Genetic drift poses two significant biosafety risks:

- Loss-of-Function Risk: Drift can lead to the inactivation or loss of safety mechanisms, such as "kill switches" or auxotrophic genes engineered to prevent survival outside the lab. This compromises biocontainment [6].

- Unpredictable System Behavior: The random fixation of alleles can alter the intended function of synthetic gene circuits, leading to unpredictable and potentially hazardous organism behavior, especially in environmental release applications [6] [7].

FAQ 4: Our small-scale fermentations show high yield, but this collapses during scale-up. Is genetic drift a factor? Yes, this is a classic scenario where genetic drift can have a major impact. Scale-up often involves a population "bottleneck"—where a small sample from the master cell bank is used to inoculate a large bioreactor. This bottleneck dramatically accelerates genetic drift, increasing the chance that a non-producing variant randomly becomes fixed in the large-scale production population [5].

FAQ 5: What are the most effective strategies to mitigate genetic drift in a production setting? Key strategies include:

- Maintaining Large Effective Population Sizes: Avoid serial passaging with small inoculums.

- Implementing Robust Selection: Use continuous and effective antibiotic selection or complementation of essential genes to maintain your construct.

- Engineering Redundancy and Stability: Incorporate genetic elements that stabilize the construct (e.g., chromosomal integration over high-copy plasmids) and design redundant safety circuits to counter random inactivation [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradual, unpredictable decline in product titer over sequential production batches. | Genetic drift leading to the accumulation of non-producing cells in the population. | Single-Cell Analysis: Use flow cytometry to check for a sub-population with low or no protein expression.Plasmid Retention Assay: Plate samples on selective and non-selective media to quantify plasmid loss rates. | - Strengthen antibiotic selection.- Switch to a more stable genetic system (e.g., chromosomal integration).- Increase the size of the inoculum for each batch. |

| Rapid failure of a biocontainment circuit (e.g., a kill switch) during long-term cultivation. | Inactivation of essential circuit components via genetic drift (e.g., point mutations, deletions). | Circuit Sequencing: Sequence the genetic circuit from a sample of the failed population to identify inactivating mutations.Functional Assay: Test the response of the failed population to the kill-switch inducer. | - Re-engineer the circuit with redundant, essential components [6].- Implement a "dead-man's switch" that requires a constant signal to remain viable. |

| High clonal variation in product yield when isolating single colonies from a production culture. | Underlying genetic heterogeneity has been revealed and fixed by drift in different sub-clones. | Clone Screening: Screen a large number of single-clone isolates for production yield to map the population's heterogeneity.Genomic Analysis: Perform whole-genome sequencing on high- and low-producing clones to identify drifted loci. | - Improve the homogeneity of the master cell bank by single-cell cloning and screening.- Implement periodic re-cloning to re-homogenize the production strain. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Genetic Drift

This section provides detailed methodologies for critical experiments to quantify and track genetic drift in your synthetic biological systems.

Protocol 1: Quantifying Plasmid Loss Rate Due to Genetic Drift

Objective: To measure the rate at which an expression plasmid is spontaneously lost from a microbial population without selective pressure, a direct measure of genetic drift's impact on system stability.

Materials:

- Your production strain containing the plasmid of interest.

- Selective growth medium (with antibiotic).

- Non-selective growth medium (without antibiotic).

- Shaker incubator.

- Spectrophotometer.

- Plating equipment and agar plates (both selective and non-selective).

Methodology:

- Inoculation and Growth: Inoculate the production strain into selective medium and grow to mid-log phase.

- Passaging: Dilute the culture 1:1000 into fresh non-selective medium. This represents one growth cycle.

- Serial Transfer: Repeat Step 2 for 50-100 generations. For each cycle, record the optical density (OD) to monitor growth.

- Plating and Counting: At regular intervals (e.g., every 10 generations), take a sample from the culture. Perform serial dilutions and plate onto both selective and non-selective agar plates.

- Calculation: After incubation, count the colonies on both sets of plates.

- Plasmid Retention Rate (%) = (Colony count on selective plates / Colony count on non-selective plates) × 100.

- Data Analysis: Plot the Plasmid Retention Rate against the number of generations. A sharp decline indicates high susceptibility to genetic drift.

Protocol 2: Amplicon Sequencing for Tracking Allele Frequency Dynamics

Objective: To precisely monitor the frequency of specific genetic variants (e.g., a specific nucleotide in a construct) in a population over time with high resolution.

Materials:

- Population samples collected at multiple time points.

- DNA extraction kit.

- PCR reagents and primers for amplifying your target genetic locus.

- Library preparation kit for next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- NGS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq).

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect cell pellets from your evolving population at defined time points (e.g., days 0, 10, 20, 30).

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from each sample.

- Target Amplification: Perform PCR to amplify the specific region of interest (e.g., your therapeutic protein gene or a safety circuit component) from each sample's DNA. Use primers with overhangs containing NGS adapter sequences.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Index each sample, pool them into a single library, and sequence on an NGS platform to achieve high coverage (>1000x per sample).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Variant Calling: Use a pipeline (e.g.,

breseqfor microbes) to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and their frequencies in each sample. - Visualization: Create a plot showing the frequency of key neutral or near-neutral alleles over time. Fluctuations in these frequencies are a direct visualization of genetic drift.

- Variant Calling: Use a pipeline (e.g.,

Amplicon Seq Workflow for Tracking Genetic Drift

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for studying and mitigating genetic drift in synthetic biology systems.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Genetic Drift Research |

|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Markers | Genes complementing a host strain's inability to synthesize an essential metabolite (e.g., an amino acid). They provide strong, continuous selection pressure to maintain engineered constructs, directly countering genetic drift [6]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Serve as visual, non-disruptive proxies for gene expression and construct stability. Flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy can track the distribution of expression levels across a population, revealing drift-driven heterogeneity. |

| Kill Switches | Genetic circuits designed to induce cell death upon specific triggers (e.g., absence of a chemical). They are a core biosafety feature, but their components are susceptible to inactivation by genetic drift, requiring redundant design [6]. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Can be used to create synthetic, programmable gene drives to bias inheritance or to actively repress the growth of genetic variants that have lost a key construct, acting as a counter-measure to drift [6]. |

| Stable Chromosomal Integration Sites | Pre-characterized genomic "safe havens" for inserting genes of interest. This avoids the high copy number and instability of plasmids, providing a more stable foundation less prone to loss via genetic drift. |

| Dual-Plasmid Selection Systems | Utilize two compatible plasmids, each carrying a different essential gene or selection marker. This creates a high genetic barrier against the complete loss of the engineered system due to random drift events. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | Bypass the use of living cells altogether for some applications. Since there is no cell division, there is no genetic drift, offering ultimate stability and control for certain types of experiments and on-demand production [7]. |

| Friulimicin C | Friulimicin C, MF:C58H92N14O19, MW:1289.4 g/mol |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-2 | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-2, MF:C22H20Cl2N4O2S, MW:475.4 g/mol |

Genetic Drift Mitigation Logic and Tools

FAQs: Understanding Drift Load in Experimental Systems

FAQ 1: What is drift load and why is it a concern in my model organism population? Drift load is the reduction in a population's mean fitness caused by the stochastic increase in frequency of deleterious mutations due to genetic drift, a process particularly potent in small populations [8]. In model organisms like mice, this is a major concern because over multiple breeding generations, all inbred and genetically modified strains are subject to genetic drift, which can alter the phenotypes associated with the underlying genetic background and compromise experimental reproducibility [9].

FAQ 2: How does the Generalized Haldane (GH) Model improve drift load quantification over traditional models? The Generalized Haldane (GH) model, based on branching processes, provides a more flexible framework for quantifying total genetic drift by accounting for variance in offspring number (V(K)) and can generate and regulate population size (N) internally [10]. This contrasts with Wright-Fisher models, which require an external N and assume a Poisson distribution of offspring (V(K) = E(K) ~1) [10]. The GH model is particularly useful for complex systems like multi-copy genes, as it estimates the total effect of genetic drift from diverse molecular mechanisms (e.g., gene conversion, unequal crossover) without requiring each mechanism to be tracked individually [10].

FAQ 3: What specific experimental readouts are used to quantify fitness loss? Fitness loss is quantified by measuring changes in key demographic rates and genetic parameters. The table below summarizes common metrics used in demo-genetic models to track fitness decline from drift load.

Table: Key Experimental Metrics for Quantifying Fitness Loss

| Metric Category | Specific Readout | Interpretation of Fitness Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Rates | Reduction in population growth rate | Direct measure of declining mean population fitness [8] |

| Increase in variance of growth rates (Demographic Stochasticity) | Heightened vulnerability to random extinction [8] | |

| Genetic Parameters | Accumulation of deleterious mutations (Genetic Load) | Genomic measure of fitness burden [8] |

| Loss of heterozygosity / Increase in inbreeding | Reduced potential to mask deleterious alleles [8] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in Quantifying Drift

Problem: Observed evolutionary rate contradicts predictions from the standard neutral model.

- Potential Cause: The standard Wright-Fisher model may under-account for the total strength of genetic drift in your experimental system, especially if it involves multi-copy genes or strong demo-genetic feedback [10].

- Solution: Apply the Generalized Haldane (GH) model to re-evaluate the neutral expectation. For instance, in ribosomal RNA genes (rDNAs), the GH model resolved the paradox of extremely fast evolution, which was incompatible with the Wright-Fisher model, by showing it was compatible with neutral evolution under a much stronger drift regime [10].

Problem: Uncontrolled drift load and background genetic drift are confounding phenotypic results.

- Potential Cause: The genetic background of your model organism population is not stable. This is a known issue in mouse strains, where genetic drift occurs over breeding generations [9].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous Genetic Stability Program. The Jackson Laboratory, for example, uses such a program to effectively limit cumulative genetic drift, thereby stabilizing phenotypes and ensuring the reliability of models for research and drug development [9].

Problem: Difficulty predicting the success of a genetic rescue intervention in a small, high-drift population.

- Potential Cause: The positive feedback loop of demo-genetic feedback, where inbreeding and drift load reduce the population size, which in turn strengthens genetic drift, creating an "extinction vortex" [8].

- Solution: Use genetically explicit, individual-based simulation models that incorporate demo-genetic feedback. Parameterize these models with your organism's specific data (e.g., demographic rates, deleterious mutation load) to test different genetic rescue scenarios (e.g., number of migrants, source population) and predict which is most likely to increase population growth and delay extinction [8].

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Quantifying Drift Load

The following diagram outlines a general experimental workflow for assessing drift load, integrating concepts from genetic and demographic measurement.

Table: Detailed Methodology for Key Workflow Steps

| Workflow Step | Detailed Methodology & Considerations |

|---|---|

| Effective Population Size (Ne) Estimation | Estimate Ne from genetic data (e.g., using linkage disequilibrium methods) or demographic data (accounting for unequal sex ratio, family size). Note that Ne is often much smaller than the census size (Nc) [8]. |

| Genetic Data Collection for Load | Use whole-genome sequencing to identify deleterious alleles. Load can be partitioned as: - Realized Load: Fitness cost from deleterious alleles in homozygous state. - Masked Load: Deleterious alleles currently hidden in heterozygotes [8]. |

| Quantifying Drift Load | Drift load is the component of the total genetic load caused by the stochastic increase in frequency of (typically weakly deleterious) mutations in small populations due to genetic drift [8]. Model fitness as a function of genotype to calculate the mean population fitness reduction. |

| Model Demo-Genetic Feedback | Use individual-based simulation software (e.g., SLiM) to build a model that includes: - Demographic stochasticity: Variance in birth/death rates. - Deleterious mutations: With defined dominance and selection coefficients. - Density feedback: How demographic rates change with population size [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Drift Load Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function & Application in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Inbred & Genetically Stable Model Organisms | Provides a defined genetic background for experiments. Sourcing from institutions with Genetic Stability Programs (e.g., The Jackson Laboratory) limits cumulative genetic drift, protecting phenotype reproducibility [9]. |

| Genetically Explicit Simulation Software | Open-source programs (e.g., SLiM, others) enable forward-time, individual-based simulation of demo-genetic feedback, allowing for in-silico testing of evolutionary hypotheses and intervention strategies [8]. |

| Synthetic Biological Constructs | Simplified genetic circuits (e.g., minimal promoter architectures) can be engineered into cells to "bend nature to understand it," distilling complex biological phenomena to their essentials to enable rigorous testing of evolutionary models [11] [12]. |

| Generalized Haldane (GH) Model | A theoretical reagent for quantifying total genetic drift from all molecular mechanisms (e.g., gene conversion, unequal crossover) in multi-copy gene systems, without the need to parameterize each mechanism individually [10]. |

| Opabactin | Opabactin, MF:C22H26N2O3, MW:366.5 g/mol |

| Ncx 1000 | Ncx 1000, MF:C38H55NO10, MW:685.8 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a genetic bottleneck and how does it lead to diversity loss? A genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in population size, often due to environmental catastrophes, habitat destruction, or disease outbreaks. This event leaves behind a small, non-representative sample of the original population's gene pool. The key consequences are:

- Loss of Allelic Diversity: The surviving population has fewer unique alleles, reducing the genetic variation available for future adaptation [13].

- Increased Genetic Drift: In smaller populations, random fluctuations in allele frequencies become more pronounced. This can lead to the fixation or loss of alleles purely by chance, rather than through natural selection [13].

- Inbreeding: Reduced population size often leads to mating between related individuals, resulting in increased homozygosity. This can reveal deleterious recessive alleles, a phenomenon known as inbreeding depression, which further threatens population viability [14] [13].

2. What is the difference between census size and effective population size (Nâ‚‘)? The census size is the total number of individuals in a population. The effective population size (Nâ‚‘) is a key parameter in population genetics that quantifies the rate of genetic drift and inbreeding [15]. It is defined as the size of an idealized Wright-Fisher population that would experience the same amount of genetic drift or inbreeding as the population under study [15]. Real-world factors like unequal sex ratios, variance in family size, and population fluctuation mean that Nâ‚‘ is almost always much smaller than the census size [15].

3. What Nâ‚‘ thresholds are critical for conservation and management? Research provides guidelines for minimum viable effective population sizes [14]:

- Nₑ ≥ 100 is required to prevent inbreeding depression in the short term.

- Nₑ ≥ 1,000 is required to retain a population's adaptive potential over the long term, allowing it to maintain genetic variation and adapt to environmental changes.

4. How can we mitigate the negative effects of population bottlenecks? The primary method to counteract diversity loss is through assisted gene flow [14].

- Genetic Rescue: Translocations from other populations can alleviate the detrimental effects of inbreeding and genetic load in a small, isolated population.

- Genetic Restoration: Introducing new genetic diversity can increase levels of genetic variation and restore a population's adaptive potential. Simulations show that regular, small-scale translocations can rapidly rescue populations from inbreeding depression [14].

5. Does all genetic diversity loss result from bottlenecks? No, other factors can also reduce diversity. Recent research indicates that population structure—such as subdivision, migration, and admixture—can heavily bias estimates of historical Nₑ and contribute to diversity loss in ways that mimic a bottleneck [16]. Furthermore, in non-bottlenecked populations, processes like learning can systematically alter survival chances and surprisingly mitigate the loss of genetic diversity caused by drift [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Diagnosing Diversity Loss in a Natural Population

You are monitoring a population that has undergone a recent decline. You suspect a genetic bottleneck is eroding diversity and fitness.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid loss of unique alleles and heterozygosity | Strong genetic drift due to small population size [13] | Estimate contemporary Nâ‚‘ using genetic marker data [15] |

| Reduced fecundity, survival, or increased disease susceptibility | Inbreeding depression [14] | Perform parental analysis to estimate inbreeding coefficients |

| Population fails to adapt to changing environment (e.g., new pathogen) | Loss of adaptive potential [14] | Use genetic data to assess if Nâ‚‘ is below 1,000 [14] |

| Historical Nâ‚‘ estimates are biased and do not match known census size | Undetected population structure (subdivision, migration, or admixture) [16] | Conduct population structure analyses (e.g., PCA, ADMIXTURE) prior to Nâ‚‘ estimation [16] |

Experimental Protocol: Estimating Recent Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘)

- Method: Use the software GONE, which estimates recent historical changes in Nâ‚‘ from a single sample of individuals using linkage disequilibrium (LD) between genetic markers [16].

- Key Consideration: GONE assumes an isolated population. If there has been recent mixture of previously separated populations or continuous migration at a low rate, the estimates of Nâ‚‘ can be substantially biased [16].

- Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect tissue or DNA from a single, random sample of individuals from the population.

- Genotyping: Genotype individuals across a high-density SNP array or via whole-genome sequencing.

- Population Structure Analysis: Critical Pre-step. Perform analyses (e.g., with ADMIXTURE or similar software) to identify genetically differentiated groups. If structure is found, restrict Nâ‚‘ estimation to these groups [16].

- Run GONE: Input the genotype data into GONE, following the software's guidelines for parameter settings.

- Interpretation: The output provides estimates of Nâ‚‘ over the past ~100-200 generations, allowing you to identify the timing and severity of a bottleneck [16].

Problem 2: Designing a Genetic Rescue Plan

Your diagnostics confirm a small, isolated population with low Nâ‚‘ and signs of inbreeding. You need to plan a translocation for genetic rescue.

| Challenge | Risk | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Outbreeding depression (reduced fitness in hybrids) | Low if populations have the same karyotype, were isolated <500 years, and are adapted to similar environments [14] | Select a donor population that is recently diverged and ecologically similar [14] |

| "Swamping" local adaptation | Gene flow can maintain local adaptation unless it is overwhelming [14] | Introduce a controlled amount of gene flow (e.g., 1-20 migrants per generation) rather than a large, one-time influx [14] |

| Donor population also has low genetic diversity | Limited benefit from genetic rescue/restoration [14] | Use a donor population that is outbred and has higher genetic diversity for a greater effect [14] |

| Introducing novel pathogens | Health risk to the recipient population | Implement a strict pathogen screening and quarantine protocol for donor individuals |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing and Monitoring Genetic Rescue

- Source Selection: Identify a potential donor population using genetic data to ensure it is differentiated but not too distantly related, following the guidelines in the table above [14].

- Translocation: Introduce a specific number of individuals from the donor population into the target population. A starting point is to aim for a rate of 1-20 migrants per generation to increase genetic diversity without immediately swamping local traits [14].

- Monitoring - Genetic: Periodically re-genotype the population to track changes in heterozygosity, allelic diversity, and Nâ‚‘.

- Monitoring - Fitness: Measure fitness traits (e.g., juvenile survival, growth rates, fecundity) before and after translocation to document the success of the genetic rescue.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | Used for amplifying genetic markers for genotyping with minimal errors, crucial for accurate diversity estimates [18]. |

| SNP Genotyping Array / Whole-Genome Sequencing Kit | Provides the raw data on genetic variation (SNPs) across the genome, which is fundamental for all downstream analyses of diversity and Nâ‚‘ [16]. |

| GONE Software | A key computational tool for estimating the recent historical effective population size (Nâ‚‘) from a single sample of genotyped individuals [16]. |

| Population Structure Software (e.g., ADMIXTURE) | Used to identify subpopulations and genetic clusters within sampled data, which is a critical pre-analysis step to avoid biased Nâ‚‘ estimates [16]. |

| recA- Competent E. coli Cells (e.g., NEB 5-alpha) | Essential for stable propagation of cloned DNA fragments, such as those used in developing genetic markers, by preventing unwanted recombination [18]. |

| ADRA2A antagonist 1 | ADRA2A antagonist 1, MF:C24H31N3O3, MW:409.5 g/mol |

| Tosposertib | Tosposertib, CAS:1418305-55-1, MF:C17H15N7, MW:317.3 g/mol |

Core Concepts Visualization

Distinguishing Drift from Selection and Mutation Pressure in Engineered Systems

Key Concepts and Definitions

What is Genetic Drift? Genetic drift is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random sampling of organisms. It is a stochastic process that can cause allele frequencies to fluctuate randomly over generations, potentially leading to the loss of genetic variation or fixation of alleles. The effects of drift are more pronounced in smaller populations [19].

What is Selection Pressure? Selection pressure refers to the effect of natural selection on a population, which can accelerate the rate of nonsynonymous mutations (positive selection) or conserve amino acids (negative/purifying selection). It is often quantified using the dN/dS ratio, where a value greater than 1 indicates positive selection, less than 1 indicates purifying selection, and equal to 1 indicates neutral evolution [20].

What is Mutation Pressure? Mutation pressure describes the effect of differential mutation rates on allele frequencies, potentially driving evolutionary change when combined with genetic drift, particularly across different genomic environments with varying effective population sizes (Nâ‚‘) [21] [22].

How do these forces interact in engineered systems? In synthetic biological systems, these evolutionary forces can interfere with designed functions. Genetic drift can cause random loss of engineered constructs, selection can favor mutations that disrupt intended functions but improve survival, and mutation pressure can systematically bias evolutionary outcomes based on underlying mutation rates [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: How can I determine if observed genetic changes are due to drift versus selection?

Problem: You observe unexpected loss or fixation of genetic elements in your engineered microbial population but cannot determine whether this results from random drift or selective processes.

Solution: Implement controlled experiments and statistical analyses to distinguish these forces:

- Population Size Manipulation: Repeat your experiment with multiple population sizes. Since genetic drift is strongly dependent on population size (effect inversely proportional to Nâ‚‘), while selection is less dependent on size, observing stronger effects in smaller populations suggests drift [25] [19].

- Replicate Lines: Maintain multiple identical populations under the same conditions. Parallel changes across most replicates suggest selection, while random, divergent changes among replicates indicate drift [19] [23].

- Fitness Assays: Compete the evolved variants against the original engineered strain in a neutral marker system. If variants show consistent fitness advantages, selection is likely operating [20].

Prevention: Maintain large population sizes (>1000 individuals) where possible, and periodically revive populations from frozen stocks to minimize generational time for drift to occur [23].

FAQ: Why is my synthetic genetic circuit losing function over generations even without apparent selective pressure?

Problem: Your carefully engineered circuit shows progressive performance degradation despite the absence of measurable fitness costs that would drive selection against the circuit.

Solution: This pattern strongly suggests genetic drift is accumulating neutral or nearly neutral mutations that affect circuit function:

- Mutation Accumulation Assay: Propagate multiple parallel lines through single-cell bottlenecks to maximize drift effects. Sequence resulting populations to identify accumulated mutations in circuit components [23].

- Circuit Robustness Analysis: Check if specific circuit components (promoters, RBS sequences, coding regions) are particularly prone to loss-of-function mutations through mutational vulnerability analysis [24].

- Parameter Sensitivity Modeling: Use computational models to determine if small changes in expression levels or kinetic parameters could explain performance declines, which would indicate susceptibility to drift [22].

Prevention: Implement redundant circuit design, use more stable genetic elements, and minimize serial passaging in your experimental workflow [23] [24].

FAQ: How do I quantify the relative contributions of drift, selection, and mutation pressure in my system?

Problem: You need to mathematically disentangle the effects of multiple evolutionary forces acting on your engineered biological system.

Solution: Apply population genetics models and statistical methods:

- Wright-Fisher Model: For haploid systems with non-overlapping generations, use this model to simulate expected drift patterns: The probability of obtaining k copies of an allele with frequency p is given by the binomial formula

(2N)!/(k!(2N-k)!) * p^k * q^(2N-k)where N is population size, and q = 1-p [19] [26]. - Moran Model: For systems with overlapping generations, this model may be more appropriate, as it accounts for stepwise birth-death processes [26].

- dN/dS Analysis: For protein-coding sequences, calculate the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates. Values significantly >1 indicate positive selection, while values <1 suggest purifying selection [20].

- Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘) Estimation: Calculate Nâ‚‘ using temporal allele frequency changes or linkage disequilibrium methods to quantify expected drift strength [25] [19].

FAQ: What strategies can mitigate genetic drift in long-term experiments?

Problem: Your research requires maintaining stable engineered populations over many generations, but drift threatens experimental reproducibility.

Solution: Implement drift-mitigation protocols:

- Cryopreservation: Archive early-generation populations and periodically restart experiments from frozen stocks rather than maintaining continuous cultures [23].

- Population Refreshment: Backcross to the original engineered strain every 5-10 generations, ensuring proper chromosomal refreshment including sex chromosomes in diploid systems [23].

- Large Population Maintenance: Use chemostats or other continuous culture devices that maintain large, well-mixed populations rather than serial transfer protocols with bottlenecks [17].

- Structured Population Management: In animal models, maintain careful pedigree records and implement rotational breeding schemes to minimize allele frequency changes [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Population Bottleneck Experiment to Assess Drift

Purpose: Quantify the impact of genetic drift on engineered genetic elements through controlled population bottlenecks.

Materials:

- Engineered microbial or mammalian cell population

- Appropriate growth medium and culture conditions

- Dilution equipment and sterile technique supplies

- PCR reagents for genotyping

- Sequencing capabilities

- Flow cytometer or other measurement device for engineered function

Procedure:

- Start with a clonal population of your engineered system.

- Establish multiple parallel lines (≥10).

- For each transfer cycle:

- Grow cultures to stationary phase

- Implement severe dilution (1:1000 to 1:10000) to create population bottlenecks

- Plate for single colonies and randomly select one to continue each line

- Maintain control lines with large population sizes (>10â¶) and no bottlenecks.

- Measure allele frequencies or circuit function every 10 generations.

- Continue for 50-100 generations.

- Sequence final populations to identify fixed mutations.

Interpretation: Greater variance in allele frequencies or circuit performance among bottlenecked lines compared to controls indicates stronger genetic drift effects [19] [23].

Protocol 2: Fluctuation Test to Measure Mutation Pressure

Purpose: Quantify mutation rates in engineered genetic elements to assess mutation pressure.

Materials:

- Engineered bacterial strain with selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance)

- Non-selective and selective growth media

- Sterile culture tubes and plating equipment

Procedure:

- Inoculate many small (0.1-0.5 mL) independent cultures from a small number of cells.

- Grow cultures to saturation without selection.

- Plate entire cultures on selective media and non-selective media for viability counts.

- Count resistant colonies on selective plates and total viable cells on non-selective plates.

- Apply the Ma-Sandri-Sarkar maximum likelihood method to estimate mutation rate from the distribution of resistant colonies across independent cultures.

Interpretation: High mutation rates indicate strong mutation pressure that could interact with drift to accelerate evolutionary change in your engineered system [21] [22].

Protocol 3: Competitive Fitness Assay to Detect Selection

Purpose: Measure relative fitness of evolved variants to detect selection.

Materials:

- Ancestral and evolved strains with distinguishable markers (e.g., different fluorescent proteins)

- Flow cytometer or selective plating method

- Appropriate growth media

Procedure:

- Mix ancestral and evolved strains in known proportions (typically 1:1).

- Propagate mixed culture for multiple generations with serial dilution.

- Sample at regular intervals and quantify strain ratios using markers.

- Calculate selection coefficient s from the change in log ratio of the two strains over time:

s = ln([Evolved]/[Ancestral])_t - ln([Evolved]/[Ancestral])_0 / t

Interpretation: Significant deviation of s from zero indicates selection acting on the evolved strain [20].

Quantitative Data and Mathematical Models

Table 1: Mathematical Models for Distinguishing Evolutionary Forces

| Model Name | Application | Key Parameters | Force Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wright-Fisher | Discrete generations, ideal for microbial systems | Population size (N), allele frequency (p) | Genetic drift [19] [26] |

| Moran | Overlapping generations, useful for mammalian cells | Birth/death rates, population size | Genetic drift (runs 2x faster than Wright-Fisher) [26] |

| dN/dS Ratio | Protein-coding sequences | Nonsynonymous/synonymous substitution rates | Selection pressure [20] |

| Coevolutionary Model | Interacting molecular components | Effective population sizes (Nâ‚‘), mutation rates (u), selection coefficients (s) | Mutation pressure-drift interaction [21] [22] |

Table 2: Expected Patterns for Different Evolutionary Scenarios

| Observation | Suggests Drift | Suggests Selection | Suggests Mutation Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes occur more rapidly in small populations | ✓ | ||

| Parallel evolution across replicates | ✓ | ||

| Consistent bias in mutation types | ✓ | ||

| dN/dS > 1 for specific genes | ✓ | ||

| Random loss of function across components | ✓ | ||

| Dependence on mutation rate exceeding neutral expectation | ✓ [22] |

Diagnostic Diagrams and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent protein markers (GFP, RFP, etc.) | Track allele frequencies without selection | Competitive fitness assays, population dynamics monitoring [17] |

| Neutral genetic markers | Distinguish strains without fitness effects | Drift measurement, population structure analysis [19] |

| Conditional lethal circuits | Measure selection coefficients | Fitness cost quantification of engineered elements [20] |

| Error-prone PCR systems | Increase mutation rates | Mutation pressure studies, evolutionary robustness testing [21] |

| CRISPR-based barcoding | Lineage tracking | Quantifying drift and selection in complex populations [23] |

| Long-read sequencers (Nanopore, PacBio) | Detect haplotypes and linked mutations | Coevolution analysis, mutation spectrum characterization [22] |

Proactive Mitigation: Computational and Experimental Strategies for Stabilizing Synthetic Functions

Leveraging Evolutionary Algorithms for Drift-Resistant Genetic Circuit Design

Core Concepts: Genetic Drift and Circuit Stability

What is genetic drift in the context of synthetic biology?

Genetic drift is a random evolutionary process that causes changes in gene frequency within a population over time. In synthetic biology, this presents a significant challenge as it can lead to the loss-of-function in engineered genetic circuits. Unlike natural selection, genetic drift is nonselective and results in nonadaptive changes. It occurs in any finite population and can overwhelm selection in small populations, reducing genetic variation within populations while increasing variation among populations [5].

Why are engineered genetic circuits particularly vulnerable to genetic drift?

Engineered genetic circuits are vulnerable to genetic drift because their function often provides no growth advantage to the host organism. In fact, cells that acquire mutations inactivating the circuit often have a growth advantage because they reduce their metabolic load. These mutant cells can outcompete functional cells in the population, leading to rapid loss of circuit function over generations. One study found that a standard Lux receiver circuit (T9002) lost function in less than 20 generations due to deletion mutations between homologous transcriptional terminators [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid loss-of-circuit function in serial propagation

Observation: Circuit function decreases significantly within 20-50 generations during serial propagation without selective pressure.

Diagnosis: This is typically caused by deletion mutations between repeated sequence elements in your genetic circuit, particularly homologous transcriptional terminators or promoter sequences [27].

Solution: Re-engineer the circuit to eliminate sequence homology:

- Replace identical terminators with functionally equivalent but non-homologous alternatives

- Avoid repeated operator sequences in promoters

- Use the following design principles to increase evolutionary half-life [27]

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Propagate cells containing the genetic circuit in liquid culture for 50+ generations with daily dilution

- Sample populations at regular intervals (every 10 generations) and measure circuit function

- Isolate plasmid DNA from non-functional populations and sequence the entire circuit

- Identify common deletion endpoints and sequence motifs in multiple independent lineages

Problem: Unstable expression despite inducible promoters

Observation: Circuit output becomes heterogeneous despite initially tight regulation.

Diagnosis: Mutations are accumulating in promoter regions or regulatory elements. Promoter mutations are selected for more than any other biological part in genetic circuits [27].

Solution:

- Use multiple, distinct inducible systems in parallel to reduce selective pressure on any single promoter

- Decrease basal expression levels to reduce metabolic burden

- Implement negative feedback loops to stabilize expression

- Consider moving the circuit to the chromosome instead of high-copy plasmids

Problem: Scar sequence mutations disrupting circuit function

Observation: Mutations frequently occur in assembly scar sequences between BioBricks.

Diagnosis: The scar sequences created by standard assembly methods create hotspots for mutations, including point mutations, small insertions and deletions, and insertion sequence (IS) element insertions [27].

Solution:

- Use alternative assembly strategies that minimize or eliminate scar sequences

- Re-engineer circuits using synthesis with optimized codons and without repeated elements

- Include selective markers within the circuit architecture when possible

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q: Can I use antibiotic resistance as selective pressure to maintain circuit function? A: While antibiotic resistance can help maintain plasmid presence, it does not ensure evolutionary stability of your specific circuit function. Studies show circuits still accumulate loss-of-function mutations even when antibiotic selection is maintained [27].

Q: How does expression level affect evolutionary stability? A: Higher expression levels consistently decrease evolutionary half-life. One study found that evolutionary half-life exponentially decreases with increasing expression levels. Reducing expression 4-fold increased evolutionary half-life over 17-fold in one tested circuit [27].

Q: What types of mutations commonly cause loss-of-function? A: Multiple mutation types are observed: deletion between homologous sequences (most common), point mutations in key regulatory elements, small insertions and deletions, large deletions, and insertion sequence (IS) element insertions that often occur in scar sequences between parts [27].

Q: Can evolutionary algorithms help design more robust circuits? A: Yes, evolutionary algorithms can explore the heuristic space for optimal combinations of genetic elements that maintain function under evolutionary pressure. This approach has successfully generated new algorithms for other complex optimization problems [28].

Stability Data and Design Principles

Table 1: Evolutionary Stability of Genetic Circuit Designs

| Circuit Design | Expression Level | Sequence Homology | Evolutionary Half-life | Primary Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T9002 (original) | High | High (terminators) | <20 generations | Deletion between terminators |

| T9002 (re-engineered) | High | None | >2-fold improvement | Point mutations |

| T9002 (optimized) | Low (4-fold reduction) | None | >17-fold improvement | Multiple, distributed |

| I7101 (original) | High | High (operators) | <50 generations | Promoter mutations |

Table 2: Design Principles for Evolutionarily Robust Circuits

| Design Principle | Implementation | Expected Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Eliminate sequence repeats | Use non-homologous terminators | 2-3 fold |

| Reduce expression level | Weaken RBS or promoters | 4-17 fold |

| Use inducible promoters | Limit expression to necessary periods | 2-5 fold |

| Distribute functional load | Modular circuit architecture | 3-6 fold |

| Chromosomal integration | Single copy reduces burden | Varies by system |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Evolutionary Stability via Serial Propagation

Purpose: Quantify the evolutionary half-life of your genetic circuit design.

Materials:

- Strain with genetic circuit

- Appropriate liquid growth media

- Inducer compounds if using inducible circuits

- Plate reader for fluorescence/absorbance measurements

Procedure:

- Start 3 independent cultures of your strain in 2mL media

- Grow cultures to late log phase (12-16 hours)

- Dilute 1:1000 into fresh media daily (approximately 10 generations per transfer)

- Every 20 generations, sample and freeze population for backup

- At each time point, measure circuit function by inducing and measuring output

- Continue for 200-300 generations or until function drops below 10% initial

- Plot normalized function vs. generations to determine evolutionary half-life

Analysis: Calculate evolutionary half-life as the number of generations until circuit function decreases to 50% of its initial value [27].

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Algorithm for Circuit Optimization

Purpose: Use evolutionary computation to generate robust circuit designs.

Materials:

- Library of biological parts (promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators)

- Assembly method for rapid construction

- High-throughput screening method

- Computational resources for algorithm execution

Procedure:

- Define genetic representation of solution domain (combination of parts)

- Establish fitness function that evaluates circuit function AND stability

- Initialize population of candidate solutions

- Apply selection, crossover, and mutation operators iteratively

- Evaluate fitness of each generation

- Continue until convergence or maximum generations reached [29] [28]

Representation Example:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Drift-Resistant Circuit Design

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Non-homologous terminators | Prevent deletion mutations | Diverse set with <70% sequence identity |

| Promoter library | Tunable expression control | Varying strengths, inducible systems |

| Standardized biological parts | Modular circuit design | BioBricks from Registry of Standard Biological Parts [30] |

| Evolutionary algorithm software | Optimize circuit configurations | Custom implementations in Python/MATLAB |

| Codon optimization tools | Reduce translational burden while maintaining function | Various web servers and standalone tools [30] |

| High-throughput screening | Evaluate circuit function and stability | Flow cytometry, microfluidics, robotic automation |

| Meds433 | Meds433, MF:C20H11F4N3O2, MW:401.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Macrocarpal I | Macrocarpal I, MF:C28H42O7, MW:490.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete methodology for designing evolutionarily robust genetic circuits:

Genetic drift, the random fluctuation of allele frequencies in a population, poses a significant threat to synthetic biological systems. In finite populations, drift can lead to the loss of beneficial genetic variants and reduce adaptive potential, undermining the stability and productivity of engineered biological functions [31] [19]. This technical support center provides resources to help researchers combat genetic drift by implementing Genotype-Preference Selection, a multi-population competitive evolutionary algorithm designed to maintain genetic diversity by explicitly considering and preserving distinct genotypes during environmental selection [32]. The guides and protocols below will assist in troubleshooting common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My synthetic population has rapidly lost genetic variation. How can I determine if genetic drift is the cause?

A: A rapid loss of variation, especially in a small population, strongly suggests genetic drift. To confirm:

- Monitor Allele Frequencies: Track changes in neutral allele frequencies over generations. Drift causes random "wobbling" of frequencies, while selection produces directional change [31] [19].

- Check Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘): Genetic drift is stronger when the effective population size is small. Your experimental Nâ‚‘ might be smaller than the census size due to bottlenecks or unequal reproductive success [31].

- Use Controls: Maintain a large, control population under the same conditions. A faster loss of heterozygosity in your smaller test population indicates drift [19].

Q2: My genotype-preference selection algorithm is not maintaining stable subpopulations. What could be wrong?

A: Instability often arises from insufficient genetic diversity during selection. Implement these strategies:

- Incorporate a Historical Survival Population: Introduce a repository of genetically diverse individuals from past generations into the competition between parent and offspring populations. This acts as a buffer against diversity loss [32].

- Apply a Genotype-Phenotype Fitness Criterion: During environmental selection, evaluate individuals based on both their genotype (using Pareto dominance for convergence) and their phenotype (ensuring diversity in expressed traits). This dual approach more precisely identifies optimal and suboptimal individuals worth preserving [32].

- Utilize Population Spectral Radius: Assess the overall convergence quality of a population as a whole, rather than evaluating individuals separately. Favor selecting populations with a minimal spectral radius, as this helps retain a wider set of genotypes [32].

Q3: I am getting inconsistent or failed results from my SNP genotyping, which is critical for tracking genotypes. How can I troubleshoot this?

A: Inconsistent genotyping data can derail diversity tracking. Follow this checklist [33]:

- Verify DNA Quality and Quantity: Use accurately quantified DNA. Degraded DNA or inhibitors in the sample can cause assay failure.

- Check for Hidden SNPs: Multiple or trailing clusters in your assay can be caused by a secondary, undetected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) under a primer or probe binding site. Search databases like dbSNP and redesign your assay if necessary.

- Use Appropriate Controls: Always include positive controls (e.g., homozygous and heterozygous genotypes) and a no-template control (NTC) to test for contamination in every run [34].

- Review Cluster Plots with Advanced Software: If your instrument's software cannot make clear calls, try specialized genotyping software (e.g., TaqMan Genotyper Software) which may have improved clustering algorithms for difficult data [33].

Q4: How do I balance the introduction of new genetic diversity with the risk of introducing deleterious traits?

A: This is a central challenge in managing genetic drift.

- Prioritize Functional Diversity: Focus on maintaining genotypic diversity that is linked to known, neutral, or beneficial phenotypic diversity, as assessed by a genotype-phenotype fitness criterion [32].

- Manage Population Structure: Use a multi-population approach. This allows new variants to be tested in semi-isolated demes, preventing a potentially deleterious variant from sweeping the entire metapopulation while still preserving it for potential future utility [31] [32].

- Implement Gradual Introgression: When introducing new genetic material, do so gradually and monitor fitness consequences across multiple generations before fully integrating it.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Multi-Population Competitive Evolutionary Algorithm with Genotype Preference

This protocol outlines the core methodology for maintaining genetic diversity against drift [32].

1. Objective To maintain high genotypic and phenotypic diversity in a synthetic population undergoing evolution, thereby mitigating the effects of genetic drift and improving adaptability.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Platform: High-throughput biofoundry automation system (e.g., an Opentrons liquid handler or equivalent) for streamlined Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles [35].

- Software: j5 DNA assembly design software, Cello for genetic circuit design, or SynBiopython library for standardized DNA design [35].

- Analysis Tools: Computational resources for running spectral radius analysis and genotype-phenotype fitness evaluation.

3. Workflow Diagram

4. Procedure 1. Initialization: Start with a population possessing high initial genetic diversity. 2. Population Selection (Genotype Preference): From the available populations, select the one with the minimal spectral radius. This metric assesses overall population convergence and favors the retention of both optimal and suboptimal genotypes. 3. Historical Population Injection: To counteract diversity loss, incorporate a "historical survival population"—a stored, genetically diverse population from a previous generation—into the current parent-offspring competition pool. 4. Competition and Recombination: Allow the parent, offspring, and historical populations to compete. Preferentially select individuals with significant genotype differences to recombine into a new, joint population. 5. Fitness Assessment: Evaluate the new population using a genotype-phenotype-based fitness criterion. This involves: * Comparing genotypes using the Pareto dominance principle to ensure convergence. * Concurrently evaluating both genotype and phenotype diversity to identify individuals with good convergence and diversity. 6. Iteration: Repeat the DBTL cycle. If genetic diversity drops below a threshold, re-inject the historical population to replenish variation.

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting SNP Genotyping for Accurate Diversity Monitoring

1. Objective To resolve common issues in SNP genotyping assays, ensuring accurate data for tracking genotypic diversity in populations.

2. Materials

- Controls: Homozygous mutant, heterozygous, homozygous wild-type, and no-template control (NTC) DNA samples [34].

- Reagents: Validated SNP genotyping assay mix, high-quality DNA template, master mix.

- Equipment: Real-time PCR instrument, computer with genotyping analysis software (e.g., TaqMan Genotyper).

3. Workflow Diagram

4. Procedure 1. No or Weak Amplification: * Accurately re-quantify DNA using a fluorometric method. Avoid degraded samples. * Check for PCR inhibitors by spiking a known control into the test sample. * Verify the reaction setup and cycling conditions. Consider increasing the cycle number [33]. 2. Poor Cluster Formation: * Trailing Clusters: Often caused by variable gDNA quality or concentration. Standardize DNA preparation protocols [33]. * Multiple Clusters: Search dbSNP for secondary polymorphisms under primer or probe sites. Redesign the assay to mask these sites as "N" in the sequence [33]. * Check if the target region is within a copy number variable region and validate with a copy number assay. 3. Failed No-Template Control (NTC): * If the NTC shows amplification, it indicates contamination. Discard the run, replace all reagents, and decontaminate workspaces [34]. 4. Software Cannot Make Calls: * Export the data and analyze it with specialized software (e.g., TaqMan Genotyper), which may have more robust clustering algorithms [33].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Genotyping Problems and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Control to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| No amplification | Degraded DNA, inhibitors, inaccurate quantification [33] | Re-quantify DNA with fluorometer; dilute to remove inhibitors; check setup [33] | No-template control (NTC) [34] |

| Single cluster only | Very low minor allele frequency (MAF), assay failure [33] | Increase sample size; use Hardy-Weinberg equation to check detectability; re-design assay [33] | Homozygous positive controls [34] |

| Multiple or trailing clusters | Hidden SNP under primer/probe; copy number variation [33] | Search dbSNP and redesign assay; validate with copy number assay [33] | Known heterozygous sample |

| Software fails to autocall | Poor separation between clusters [33] | Analyze data with advanced software (e.g., TaqMan Genotyper) [33] | Full set of genotype controls [34] |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application in Diversity Maintenance |

|---|---|

| Biofoundry Automation | Integrated robotic platform to execute high-throughput Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles, enabling rapid prototyping and testing of diverse genetic constructs [35]. |

| j5 DNA Assembly Software | An open-source tool for automated design of DNA assembly strategies, standardizing the "Build" phase and facilitating the creation of complex genetic variants [35]. |

| TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays | Validated assays for accurate allele frequency determination, crucial for monitoring population diversity and detecting drift [33]. |

| Synthetic Biology Software (Cello, SynBiopython) | Computational tools for designing genetic circuits (Cello) and standardizing DNA design across platforms (SynBiopython), enhancing the "Design" phase [35]. |

| Historical Survival Population Archive | A biobank of cryopreserved, genetically diverse cell lines or organisms from past generations, used to reintroduce lost variation into a population [32]. |

| Anticancer agent 128 | Anticancer agent 128, MF:C26H38N4O4, MW:470.6 g/mol |

| Glucocheirolin | Glucocheirolin, MF:C11H20NO11S3-, MW:438.5 g/mol |

Visualizations and Workflows

Core MPCEA-GP Algorithm Workflow

This diagram illustrates the logical flow of the Multi-Population Competitive Evolutionary Algorithm based on Genotype Preference (MPCEA-GP), which is central to countering genetic drift [32].

Archiving Historical Genotypes to Counteract Diversity Loss Over Time

FAQs on Genetic Drift and Archiving

What is genetic drift and why is it a concern for my research? Genetic drift is a fundamental evolutionary process characterized by random fluctuations in allele frequencies within a population from one generation to the next [17]. These random changes can lead to the permanent loss of genetic variants, reducing diversity [36]. For researchers, this is a critical concern because genetic drift can change the phenotype of your model organisms and compromise the reproducibility of your experiments over time, even under identical laboratory breeding conditions [23].

How can archiving historical genotypes help counteract genetic drift? Archiving creates a stable, cryogenically preserved repository of genetic material [37]. This serves as an insurance policy against the random changes that accumulate in living colonies. If genetic drift occurs, you can recover the original genetic background of your strain from these frozen archives, effectively "resetting" the genetic clock and restoring the original phenotypes and experimental conditions [23].

What are the key components of a effective genetic archive? A proper genetic archive requires more than just freezing samples. Key components include [37]:

- Secure, Long-Term Storage: Reliable cold storage units (e.g., ultra-low temperature freezers or liquid nitrogen) with minimal freeze-thaw cycles.

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Detailed, written protocols for all tasks, from sample accessioning and cataloging to loans and disposal.

- Comprehensive Data Management: Meticulous tracking of all associated data (e.g., using Darwin Core standards), including pedigree information and the number of inbred generations.

- Trained Personnel: Staff trained using the written SOPs to ensure accuracy and consistency in all repository procedures.

My mouse colony is small; how often should I refresh the genetics? For long-term maintenance, it is recommended to refresh the genetic background of your strain by backcrossing to the appropriate inbred genetic background every 5-10 breeding generations to minimize the risk of drift [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Genetic Drift Scenarios

Problem: Unexpected Phenotype in a Previously Stable Model Organism

This is a common signal that genetic drift may have occurred in your colony [23].

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Accumulated spontaneous mutations [23] | Sequence the genome of affected individuals and compare to original background. Review breeding logs for number of generations. | Recover the strain from your frozen genetic archive. If unavailable, refresh the genetic background via backcrossing [23]. |

| Substrain divergence | Verify the source and nomenclature of your strain. Compare your experimental results with recent literature. | Always report detailed substrain and breeding strategy in publications. Obtain new breeding stock from the original, trusted vendor [23]. |

Problem: Loss of Genetic Diversity in a Synthetic Genetic Circuit Population

This can occur even without selective pressure, due to random chance in small populations [17] [36].

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Small effective population size [36] | Calculate the population size used in your experiments. Monitor allele frequencies over time. | Increase the population size for experiments. For long-term storage, archive a large number of distinct genetic variants [37]. |

| Bottleneck event during culture passage | Review lab protocols for steps that involve a drastic reduction in cell numbers. | Archive master stocks of the entire population. When propagating, use a large inoculum to maintain diversity [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol 1: Backcrossing to Refresh Genetic Background

This protocol is used to minimize the impact of genetic drift by reintroducing the original, stable genome from a trusted vendor into your colony [23].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Inbred Mice from Trusted Vendor: The source of the original, non-drifted genetic background (e.g., C57BL/6J from JAX).

- Homozygous "Drifted" Colony Mice: The mice from your own colony that need to be refreshed.

Workflow:

Steps:

- Initial Cross: Breed a homozygous female from your "drifted" colony with an inbred male from a trusted vendor. This produces the first backcross generation (N1), which is heterozygous.

- First Backcross: Take an N1 heterozygous male and mate it with an inbred female from the trusted vendor. This produces the N2 generation.

- Second Backcross: Take an N2 heterozygous male and mate it with an inbred female from the trusted vendor. This produces the N3 generation. By this step, the sex chromosomes are fully refreshed.

- Re-establish Homozygosity: Intercross male and female N3 heterozygotes to re-homozygose your gene of interest (e.g., a knockout allele) on the refreshed genetic background [23].

Protocol 2: Establishing a Cryopreserved Genetic Archive

Long-term cryopreservation is the most robust method to halt genetic drift entirely for a strain [23] [37].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Cryoprotectant: Such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or glycerol.

- Aseptic Collection Supplies: Sterile tubes, pipettes, and labels.

- Controlled-Rate Freezer: For gradual cooling to prevent ice crystal formation.

- Long-Term Storage Vessel: Liquid nitrogen cryovats or ultra-low temperature freezers (-80°C or colder).

Workflow:

Steps:

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect the biological material to be preserved (e.g., sperm, embryos, engineered bacterial cells).

- Cryopreservation: Mix the sample with an appropriate cryoprotectant solution. Use a controlled-rate freezer to slowly cool the samples to the desired storage temperature, minimizing cold shock and ice damage.

- Long-Term Storage: Transfer the frozen samples to a long-term storage vessel, ideally in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen (-135°C to -196°C) [37].

- Data Cataloging: Log all sample information into a secure database. Essential data includes strain identity, genotype, date, passage number, and storage location [37].

- Viability Testing: After freezing, thaw a test sample to confirm viability and the ability to recover a live organism or functional culture.

- Strain Recovery: When needed, thaw an archived vial to regenerate the original, non-drifted strain for experiments [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Inefficient Cell Killing in Deadman Kill Switches