Phylogenetic vs. Functional Diversity: A Comparative Framework for Modern Conservation Strategy

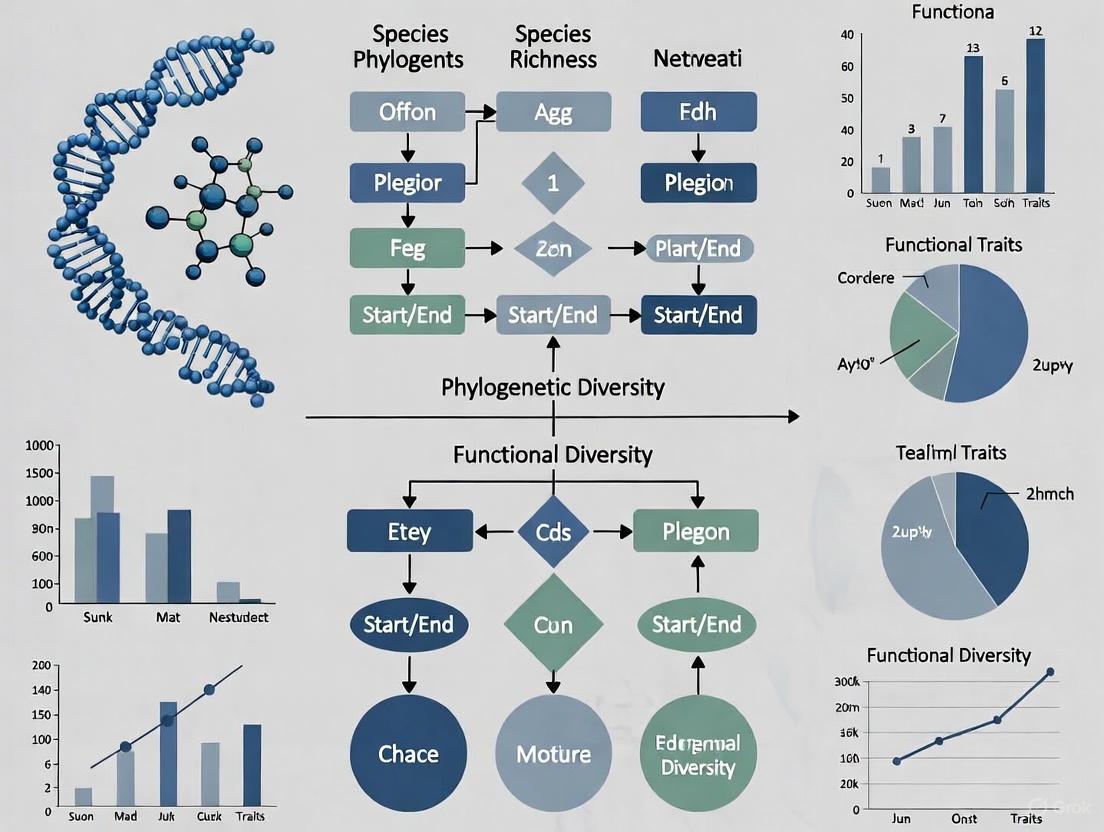

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of phylogenetic diversity (PD) and functional diversity (FD) as critical, yet distinct, metrics for conservation.

Phylogenetic vs. Functional Diversity: A Comparative Framework for Modern Conservation Strategy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of phylogenetic diversity (PD) and functional diversity (FD) as critical, yet distinct, metrics for conservation. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational theory that PD can act as a surrogate for FD—the 'phylogenetic gambit'—and presents mounting global evidence of their frequent decoupling. The content details practical methodologies for measurement, examines pitfalls in prioritization, and validates approaches through terrestrial and forest ecosystem case studies. The synthesis concludes that effective conservation requires integrating both facets to fully capture evolutionary history and ecological function, thereby ensuring the long-term resilience of biodiversity.

The Evolutionary and Ecological Pillars of Biodiversity

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) is a measure of biodiversity that quantifies the evolutionary history represented by a set of species. Formally defined by Faith (1992), it calculates the sum of the lengths of all phylogenetic branches that connect a set of species on the tree of life [1]. This metric reflects the evolutionary breadth of lineages within a given area, capturing the total independent evolutionary history in a sample [2] [3]. The fundamental premise is that branch lengths on phylogenetic trees represent relative numbers of new features arising along evolutionary lineages, making PD an indicator of "feature diversity" - the variety of biological traits and characteristics [1].

Functional Diversity (FD) measures the variety of ecological roles organisms perform within an ecosystem, based on their functional traits rather than evolutionary relationships [4]. It considers the range, distribution, and relative abundance of functional traits within a community, moving beyond simple species counts to understand what different organisms actually do in ecological systems [4] [5]. Functional traits are specific, measurable characteristics (e.g., leaf size, rooting depth, dietary preferences) that influence organism performance and ecosystem processes [4].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Comparison of Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity

| Aspect | Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) | Functional Diversity (FD) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Evolutionary history and relationships | Ecological roles and functions |

| Basic Unit | Phylogenetic branch lengths | Measurable functional traits |

| Foundation | Evolutionary tree of life | Ecological strategy variation |

| Time Scale | Deep evolutionary time (millions of years) | Contemporary ecological time |

| Key Rationale | Proxy for feature diversity and evolutionary potential | Direct measure of ecological function |

Measurement Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Quantifying Phylogenetic Diversity

The standard measurement approach for PD follows Faith's method: PD = Sum of branch lengths in the minimum spanning path connecting a set of species on a phylogenetic tree [1]. The phylogenetic trees are typically constructed from molecular data (DNA sequences) with branch lengths calibrated using molecular clocks to represent evolutionary time [5]. Additional metrics include Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD) and Mean Nearest Taxon Distance (MNTD), which offer different perspectives on phylogenetic structure [3].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Diversity Assessment

| Approach Type | Phylogenetic Diversity Methods | Functional Diversity Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Measures | Faith's PD, MPD, MNTD [5] [3] | Functional richness, evenness, divergence [4] |

| Data Requirements | Molecular sequences, dated phylogenies [5] | Measured functional traits [6] |

| Analysis Tools | Phylogenetic comparative methods, spatial phylogenetics [3] | Trait-based ordination, clustering algorithms [5] |

| Discrete Alternatives | Taxonomic distinctness based on hierarchy [5] | Predefined functional groups [5] |

Assessing Functional Diversity

Functional diversity measurement employs three primary approaches [5]:

- Pairwise distances: Mean or sum of pairwise trait differences between species

- Hierarchical clustering: Sum of branch lengths connecting species in trait-based dendrograms

- Multidimensional ordination: Volume or area encompassed by species in multivariate trait space

These methods operate through a standardized workflow that progresses from trait measurement to diversity quantification. The process begins with careful selection and measurement of functional traits relevant to ecological processes, followed by calculating functional distances between species to construct a trait space. Finally, appropriate diversity indices are computed to capture different aspects of functional variation within communities [5].

Functional Diversity Assessment Workflow

Empirical Evidence and Comparative Performance

Relationship Between PD and FD

The fundamental relationship between phylogenetic and functional diversity represents a central question in conservation science. The "phylogenetic gambit" hypothesis proposes that PD serves as a reliable proxy for functional diversity, based on the assumption that evolutionary relationships predict ecological function [7]. However, recent large-scale empirical tests reveal a more complex relationship.

A comprehensive study analyzing >15,000 vertebrate species across mammals, birds, and tropical marine fishes found that maximizing PD results in an average gain of 18% of FD compared to random selection [7]. This suggests PD generally captures functional aspects, but significant variation exists - in one-third of comparisons, maximizing PD actually resulted in less FD than random choice [7]. This indicates context-dependency in the PD-FD relationship, influenced by taxonomic group, trait type, and spatial scale.

Differential Responses to Environmental Gradients

Research in natural river ecosystems demonstrates how PD and FD respond differently to environmental disturbances. A study comparing dammed and undammed rivers found that while species diversity (SD) decreased significantly in both systems during seasonal changes, PD and FD showed more nuanced patterns: they "significantly declined during September in the undammed river, but they did not significantly change in the dammed river" [8]. This indicates that PD and FD are more sensitive than species richness for detecting disturbance effects on ecosystem integrity.

Large-scale geographical studies of forest communities reveal consistent patterns in functional trait moments along environmental gradients. Research across 250 forest dynamics plots in subtropical China demonstrated that functional trait moments shift significantly along latitudinal, longitudinal, and elevational gradients, with climate explaining 35-69% of variation in community-weighted mean traits, and lesser proportions for variance (21-56%), skewness (14-31%), and kurtosis (16-30%) [6]. Environmental filtering, particularly climate variability, emerged as the dominant assembly process shaping functional composition.

Table 3: Empirical Performance Comparison from Conservation Studies

| Study Context | Phylogenetic Diversity Findings | Functional Diversity Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebrate Conservation (15,000 species) | 18% average FD gain when maximizing PD; ineffective in 1/3 of cases [7] | PD considered unreliable as exclusive FD proxy [7] |

| River Ecosystem Monitoring | Sensitive to hydrological disturbances; declined in undammed rivers [8] | Better indicator of community stability than species diversity [8] |

| Forest Community Assembly | Serves as proxy for unmeasured traits; captures evolutionary history [2] | Directly linked to ecosystem functioning; shaped by environmental filters [6] |

| Conservation Prioritization | Captures evolutionary distinctness and feature diversity [9] | Directly addresses ecological roles and ecosystem services [4] |

Research Applications and Implementation

Successful implementation of phylogenetic and functional diversity assessments requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The research reagents and computational resources needed for comprehensive diversity assessment include both conceptual frameworks and analytical tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Diversity Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Reconstruction | Molecular sequences, clock models, tree-building algorithms [5] [3] | Building dated phylogenies for PD calculation |

| Trait Measurement Protocols | Standardized trait measurements (SLA, LDMC, WD, etc.) [6] | Quantifying functional characteristics for FD assessment |

| Diversity Metrics | Faith's PD, functional richness/evenness/divergence [4] [1] | Calculating diversity indices from primary data |

| Statistical Frameworks | Null models, structural equation modeling, multivariate analysis [8] [5] | Testing hypotheses about diversity patterns and drivers |

| Environmental Data | Climate records, soil chemistry, topographic metrics [6] | Linking diversity patterns to environmental gradients |

Conservation Decision-Making Framework

The integration of phylogenetic and functional diversity metrics follows a logical decision pathway that begins with clear conservation objectives and progresses through methodological choices to final prioritization. This framework helps researchers and practitioners select the most appropriate diversity metrics based on their specific conservation goals, whether focused on evolutionary heritage, ecosystem functioning, or comprehensive biodiversity protection.

Conservation Decision-Making Framework

Phylogenetic and functional diversity represent complementary rather than competing biodiversity dimensions. PD serves as a broad proxy for feature diversity and evolutionary potential, valuable for capturing unknown trait variation and evolutionary history [9] [1]. FD directly measures ecological trait variation, providing mechanistic understanding of ecosystem functioning and services [4]. The empirical evidence indicates that PD generally captures functional aspects, but with sufficient inconsistency (failing in approximately one-third of cases) that it should not be relied upon as the sole diversity metric in conservation planning [7].

Future research priorities include: (1) better understanding the conditions under which PD reliably predicts FD across different taxa and ecosystems; (2) developing integrated conservation frameworks that simultaneously optimize phylogenetic and functional dimensions; and (3) addressing methodological challenges in phylogenetic reconstruction and trait selection that currently limit comparative applications [9]. For conservation practitioners, the choice between these metrics depends critically on specific objectives - PD for safeguarding evolutionary history and option value, FD for maintaining ecosystem functioning and services, and their integration for comprehensive biodiversity conservation.

In the face of the ongoing biodiversity crisis, conservationists are forced to make difficult choices about which species to protect with limited resources. One prominent strategy that has emerged is to prioritize phylogenetic diversity (PD)—the total evolutionary history represented by a set of species. This approach is underpinned by the "Phylogenetic Gambit" hypothesis: the assumption that maximizing PD will also capture greater functional diversity (FD)—the variety of ecological traits and functions performed by organisms. The gambit posits that since species traits often reflect shared evolutionary history, their phylogeny should serve as a useful proxy for unmeasured traits. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the reliability of PD as a surrogate for FD, synthesizing empirical evidence and methodological approaches to inform conservation and research strategies.

Empirical Evidence: Testing the Gambit

A landmark study directly tested the Phylogenetic Gambit using extensive global datasets for mammals, birds, and tropical fishes, encompassing over 15,000 vertebrate species and ecologically relevant traits such as body mass, diet, and foraging strata [10] [11].

The core finding was that while prioritizing PD for conservation provides a net positive gain in captured FD on average, this strategy is surprisingly unreliable [10] [12]. The analysis measured the surrogacy (SPD-FD) of PD for FD, which quantifies how much more FD a PD-maximized set of species captures compared to a randomly chosen set, relative to the maximum possible FD.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from the Mazel et al. (2018) Study

| Metric | Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Average Surrogacy (SPD-FD) | +18% gain in FD [10] | On average, maximizing PD captures more FD than a random strategy. |

| Reliability | Failed in 36% of comparisons [10] [12] | In over one-third of tests, a PD-max set contained less FD than a random species set. |

| Range of Surrogacy | -85% to +92% [10] | The performance of the PD strategy is highly variable across different species pools. |

| Success Rate | PD-based selection was best in 64% of cases [10] | Slightly more reliable than random choice, but not robust enough for guaranteed success. |

The study concluded that while the phylogenetic gambit pays off on average, it constitutes a "risky conservation strategy" due to its high failure rate [10]. This risk was found to be higher in species-rich pools, where functional redundancy among species is greater, and in certain older taxonomic orders [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The empirical test of the Phylogenetic Gambit relies on a structured workflow integrating large-scale phylogenetic, functional trait, and geographic data. The following diagram illustrates the core experimental protocol.

Experimental Workflow for Testing the Phylogenetic Gambit

Detailed Methodology

Data Acquisition and Species Pool Definition: Research begins by defining the set of species (the "pool") for analysis, which can be taxonomic (e.g., a family) or geographic (species co-occurring in a region) [10]. For these species, two primary datasets are compiled:

- Phylogenetic Data: A time-calibrated phylogenetic tree representing the evolutionary relationships among all species in the pool.

- Trait Data: Empirical data on ecologically relevant functional traits for as many species as possible. In the seminal study, this included traits like body mass, diet, activity cycle, and foraging strata [10].

Diversity Calculation:

- Phylogenetic Diversity (PD): Calculated as the sum of the branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree connecting all species in a subset [13].

- Functional Diversity (FD): Often measured as functional richness, which quantifies the volume of trait space occupied by a set of species, typically using a convex hull approach [10].

Comparative Analysis and Surrogacy Measurement: This is the core test. For a given number of species (k), the analysis compares three selection strategies [10]:

- FD-Maximization: The optimal set of species that maximizes FD (used as a benchmark).

- PD-Maximization: The set of species that maximizes PD.

- Random Selection: Numerous random sets of k species are chosen to establish a baseline. The key metric, Surrogacy (SPD-FD), is then computed. This measures the FD captured by the PD-maximized set relative to the FD captured by a random set, standardized against the maximum possible FD (from the FD-maximized set) [10]. A positive value indicates the PD strategy is better than random, while a negative value means it is worse.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Conducting robust tests of the Phylogenetic Gambit requires a suite of data, analytical tools, and software.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Data | Time-calibrated molecular phylogenies built from gene sequences (e.g., rRNA, protein-coding genes) [14]. Function: Provides the evolutionary scaffold for calculating PD. |

| Functional Trait Databases | Global trait compilations (e.g., for mammals, birds, fish). Function: Provides standardized morphological, physiological, and ecological trait data for FD calculation. |

| Geographic Range Data | Species distribution maps from sources like the IUCN. Function: Allows definition of geographic species pools for assemblage-level analyses. |

| Analytical Software & Platforms | R statistical software with packages for phylogenetics (ape, phangorn), functional diversity (FD), and multivariate analysis. Function: The primary environment for data integration, diversity calculation, and statistical testing. |

| Genomic Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing (e.g., RAD-seq, WGS, RNA-seq) [15]. Function: Enables the construction of robust phylogenies and exploration of genetic architectures of traits. |

| Bz-DTPA (hydrochloride) | Bz-DTPA (hydrochloride), MF:C22H31Cl3N4O10S, MW:649.9 g/mol |

| Cy5-PEG2-TCO | Cy5-PEG2-TCO, MF:C47H65ClN4O5, MW:801.5 g/mol |

Critical Debate and Research Perspectives

The findings of the Mazel et al. study have sparked significant debate, highlighting divergent perspectives in the field.

The "Risky Strategy" Perspective: The original authors argue their empirical test, focused on ecologically relevant traits, is a valid and critical assessment of a key assumption in conservation planning [16]. They stress that the presence of phylogenetic signal (where closely related species share similar traits) does not automatically guarantee that maximizing PD will effectively capture FD, a point supported by both empirical and theoretical work [10] [16].

The "Incomplete Test" Perspective: Critics, notably Faith (the original proponent of PD), argue that the test is incomplete. They contend that defining FD based on a handful of ecological traits misrepresents the broader concept of "feature diversity" that PD was designed to capture [12]. This feature diversity includes a vast array of phenotypic and genetic characters, forming the basis for biodiversity's "option value"—its potential to provide future benefits to humanity that are as-yet-unknown [13] [12]. From this viewpoint, PD remains a well-corroborated measure for capturing this general feature diversity and its associated option value.

The evidence demonstrates that the Phylogenetic Gambit is not a universally reliable guide for conservation. While prioritizing phylogenetic diversity is, on average, a better strategy than random selection for capturing functional diversity, its high rate of failure (36%) makes it a risky single criterion for critical conservation decisions [10].

The choice between PD and FD is context-dependent. For conservation goals aimed at preserving specific ecosystem functions driven by known traits, direct measurement of FD is superior where data exists. However, PD remains a powerful tool for capturing the broader evolutionary heritage and the "option value" of biodiversity, especially when trait data is incomplete [16] [13] [12].

Future research should focus on expanding these tests to more taxonomic groups, particularly plants, and incorporating a wider range of traits, including molecular and physiological characters [16] [15]. Bridging the gap between theoretical tests and on-the-ground conservation application will be essential for developing robust, evidence-based strategies to safeguard the tree of life and its functions.

Phylogenetic Niche Conservatism (PNC) represents a fundamental evolutionary pattern where closely related species retain similar ecological characteristics and environmental tolerances over evolutionary time. This tendency for lineages to conserve their ancestral niche traits creates a powerful theoretical link between species' evolutionary relationships and their functional traits [17]. While PNC is often discussed in relation to phylogenetic signal (the statistical tendency for related species to resemble each other), a strict definition suggests PNC represents an extreme case where species are more similar than expected based on their phylogenetic relationships alone [17]. This conceptual framework has profound implications for understanding how biodiversity is distributed across landscapes and how it might respond to environmental change, making it particularly relevant for conservation science.

The ongoing debate in evolutionary biology centers on whether PNC primarily represents a pattern of trait distribution or a mechanistic process involving evolutionary constraints. From a process perspective, PNC results from multiple factors including genetic constraints, stabilizing selection, and developmental constraints that limit niche evolution [18]. This mechanistic view helps explain why species often occupy similar environments to their ancestors and why major biogeographic patterns, such as latitudinal diversity gradients, may persist over evolutionary timescales. Within conservation biology, recognizing these patterns and processes provides a critical foundation for prioritizing species and ecosystems based on their evolutionary distinctness and potential contributions to future biodiversity.

Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Phylogenetic Niche Conservatism

Researchers employ several well-established statistical metrics to quantify the degree of phylogenetic signal in species traits, providing empirical evidence for PNC. These metrics form the essential toolkit for testing hypotheses about evolutionary constraints and trait evolution across phylogenies.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Phylogenetic Signal

| Metric | Statistical Basis | Interpretation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pagel's λ | Brownian motion model likelihood ratio | λ=0 indicates no phylogenetic signal; λ=1 follows Brownian motion expectation | Testing evolutionary hypotheses under different models of trait evolution [19] [17] |

| Blomberg's K | Mean squared error vs. phylogenetic distance | K=1 matches Brownian motion; K<1 indicates less resemblance than expected; K>1 indicates strong conservatism | Comparing phylogenetic signal across different traits and clades [19] [17] |

| Moran's I | Spatial autocorrelation adapted for phylogeny | Values >0 indicate positive autocorrelation (related species are similar) | Assessing trait distribution across phylogeny without specific evolutionary model [19] [17] |

| Abouheif's C~mean~ | Test for phylogenetic independence in comparative data | Significant values indicate non-random distribution of traits across phylogeny | Detecting phylogenetic signal without branch length information [19] [17] |

Recent applications demonstrate how these metrics illuminate evolutionary patterns in diverse taxa. In Arctic macrobenthos studies, researchers applied Pagel's λ, Blomberg's K, Moran's I, and Abouheif's C~mean~ to 21 functional traits across 50 species, revealing how phylogenetic constraints shape community assembly in rapidly changing fjord ecosystems [19]. Similarly, studies on Dipterocarpaceae, a keystone plant family in Southeast Asian tropics, found "moderate to strong phylogenetic signal" in plant traits, indicating significant PNC that shapes species distributions and functional diversity [20]. These quantitative assessments provide critical evidence for how evolutionary history constrains or facilitates ecological adaptation.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating PNC

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods Framework

The standard methodological approach for evaluating PNC involves a sequence of integrated steps that combine phylogenetic reconstruction with trait data analysis:

Phylogeny Reconstruction: Molecular data (typically mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) for animals or chloroplast markers for plants) are collected for target species. Sequences are aligned using algorithms like MUSCLE or CLUSTAL W, with phylogenetic trees constructed using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods in software such as MEGA X or BEAST [19]. The mtCOI region offers particularly high taxonomic resolution due to rapid evolution and conserved priming sites, enabling broad amplification across diverse taxonomic groups [19].

Trait Data Compilation: Functional traits with ecological relevance are compiled from literature, museum collections, or direct measurement. For macrobenthos, this typically includes body size, feeding mode, habitat position, and reproductive strategies [19]. For woody plants, this might include leaf traits, wood density, height, and drought tolerance [20] [21].

Phylogenetic Signal Testing: The compiled trait data are tested against the phylogeny using the metrics described in Table 1, implemented in R packages such as

phytools,ape, oradephylo.Evolutionary Model Fitting: Alternative models of trait evolution (Brownian Motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, Early Burst) are fitted to the data and compared using information criteria (AICc or BIC) to identify the best-supported evolutionary process [19].

Multivariate Integration: Techniques like phylogenetic Principal Component Analysis (pPCA) account for phylogenetic non-independence while identifying major axes of trait variation [19]. This approach generates composite phylogenetic primary-axis species scores (PPASS) that summarize major trait variation while accounting for shared ancestry.

Model-Based Approaches to Trait Evolution

The interpretation of PNC depends heavily on comparing alternative evolutionary models that represent different processes of trait evolution:

Table 2: Evolutionary Models for Trait Evolution Analysis

| Model | Mathematical Foundation | Biological Interpretation | Relationship to PNC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian Motion (BM) | Random walk with variance proportional to time | Neutral evolution; traits diverge randomly without constraint | Baseline expectation; Blomberg's K=1 indicates fit to BM [19] |

| Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) | Random walk with stabilizing selection toward an optimum | Constrained evolution with adaptive peaks; traits under stabilizing selection | Stronger signal than BM suggests PNC; constraint around optimum [19] [18] |

| Early Burst (EB) | Exponential decay in evolutionary rate through time | Rapid diversification early in clade history with slowing rates | Suggests decreasing evolutionary lability; early PNC establishment [19] |

The model selection process provides critical insights into whether trait distributions reflect recent adaptive responses to contemporary environments or deeper phylogenetic constraints. As noted in Arctic macrobenthos research, "disentangling whether trait distributions reflect recent adaptive responses to present-day environments or deep phylogenetic constraints is key to understand how communities assemble and persist under constant environmental change" [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analyses

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools

| Category/Reagent | Specific Examples | Primary Function in PNC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Markers | mtCOI, rbcL, matK, ITS | Phylogeny reconstruction; provides evolutionary framework for trait analyses [19] |

| Sequence Alignment | MUSCLE, CLUSTAL W | Multiple sequence alignment for accurate phylogenetic inference [19] |

| Phylogenetic Software | MEGA X, BEAST, RAxML | Tree building and evolutionary model testing [19] |

| Comparative Methods | R packages: phytools, ape, geiger | Implementation of phylogenetic signal metrics and evolutionary models [19] [20] |

| Trait Databases | TRY Plant Trait Database, custom collections | Standardized trait data for comparative analyses [20] [21] |

Conservation Implications: Phylogenetic vs. Functional Diversity

The theoretical framework of PNC has practical applications in conservation prioritization, particularly in the ongoing discussion about the value of phylogenetic diversity (PD) versus functional diversity (FD). Phylogenetic diversity represents the sum of phylogenetic branch lengths connecting a set of species, intended to capture their total feature diversity (both known and unknown) [22] [9]. The fundamental rationale is that PD serves as a proxy for the "option values" of biodiversity - preserving evolutionary potential for future benefits and ecosystem resilience [9].

However, recent debates have questioned whether PD reliably captures functional diversity, with some studies suggesting PD "captures functional diversity unreliably" [22]. Advocates for PD counter that this perspective too narrowly defines feature diversity as only known functional traits, neglecting PD's capacity to conserve unknown features with potential future utilitarian value, such as pharmaceutical compounds or adaptive genetic variations [22]. Empirical examples supporting this broader view include discoveries that funnel-web spider venom provides medication to prevent stroke-related brain damage, and Tasmanian Devil milk contains substances that fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria [22].

Conservation programs like the EDGE of Existence (Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered) explicitly incorporate phylogenetic distinctness into prioritization schemes, recognizing that the extinction of evolutionarily distinct species represents irreversible loss of unique evolutionary history [22] [9]. This approach highlights the conservation significance of PNC - when traits are phylogenetically conserved, phylogenetic diversity effectively captures functional diversity, but when traits are labile, the relationship decouples.

Conceptual Workflow and Theoretical Framework

Emerging Insights and Theoretical Synthesis

Recent simulation studies provide novel insights into the relationship between PNC and diversification rates, suggesting that niche conservatism promotes biological diversification rather than limiting it. Contrary to intuitive expectations that niche lability might increase diversification by allowing adaptation to new environments, research demonstrates that "niche conservatism promotes biological diversification, whereas labile niches—whether adapting to the conditions available or changing randomly—generally led to slower diversification rates" [23]. This counterintuitive pattern emerges because conserved niches increase range fragmentation and population isolation, facilitating allopatric speciation despite potentially higher extinction rates.

The relationship between PNC and speciation mechanisms reveals important nuances. PNC primarily enhances diversification through increased allopatric speciation rather than reduced extinction, as populations with conserved niches are more likely to become geographically isolated by environmental barriers [23]. This theoretical framework helps explain empirical patterns observed across diverse taxa, from the phylogenetic conservatism in dipterocarp traits shaping tropical forest assembly [20] to the evolutionary constraints on macrobenthic functional traits in Arctic fjords [19].

These findings have practical significance for conservation in rapidly changing environments. When PNC is strong, phylogenetic diversity effectively captures functional diversity, supporting the use of PD as a conservation prioritization tool. However, when traits evolve rapidly or converge in unrelated lineages, the relationship between phylogeny and function becomes decoupled, potentially undermining PD-based conservation approaches [22] [9]. Understanding the theoretical link between traits and evolutionary relationships through the framework of PNC therefore provides essential guidance for developing effective conservation strategies that preserve both the evolutionary history and functional capabilities of biodiversity.

Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) represents the cumulative evolutionary history of a set of species, measuring the breadth of evolutionary lineages present in a community. Functional Diversity (FD) quantifies the diversity and distribution of functional traits within a set of species, reflecting the variety of ecological roles performed. Together, PD and FD provide a more holistic view of biodiversity than species richness alone, capturing the evolutionary uniqueness and ecological functioning of ecosystems. These metrics are increasingly vital for conservation planning as they predict ecosystem resilience, niche complementarity, and ecosystem service provision. Current research emphasizes that conservation strategies based solely on taxonomic diversity may overlook critical dimensions of biodiversity, necessitating integrated approaches that protect both evolutionary history and ecological function.

The tropics, encompassing regions such as the Neotropics, Afrotropics, and Oriental realms, host the planet's most concentrated terrestrial biodiversity. This review synthesizes evidence demonstrating that these regions also serve as the epicenters for traded phylogenetic and functional diversity, with profound implications for global conservation policy and practice.

Quantitative Evidence: Global Patterns of Traded PD and FD

Analysis of a global dataset of 5,454 traded bird and mammal species reveals distinct spatial patterns in phylogenetic and functional diversity. The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings from global assessments:

Table 1: Global Hotspots of Traded Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity

| Metric | Taxon | Primary Hotspots | Secondary Hotspots | Standardized Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) | Birds | Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Ghats, mainland Southeast Asia, Sumatra, Himalaya, Ethiopian Plateau | Neotropical dry forests and savannas (Caatinga, Cerrado, Chaco) | ses.PD = 5.11 (overdispersed) |

| Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) | Mammals | Congo Basin, Guinea Forest, Western Ghats | Eastern United States, Tropical Andes, Brazilian Atlantic, Saharan periphery, Australasia | ses.PD = 2.68 (less overdispersed) |

| Functional Diversity (FD) | Birds & Mammals | Tropical regions (Neotropics, Orient, Afrotropics) | - | Large-bodied, frugivorous, canopy-dwelling species disproportionately targeted |

| EDGE Richness | Birds & Mammals | Oriental and Afrotropical realms | Western Amazonia, Borneo | Tropical realms account for higher proportion of cumulative EDGE score |

The data demonstrates that epicenters of traded PD are concentrated in tropical biogeographic realms, with the top 5% of cells located primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, the Western Ghats, mainland Southeast Asia, and Sumatra [24]. The standardized effect size of traded PD (ses.PD), which measures phylogenetic breadth relative to species richness, shows that avian trade is more phylogenetically overdispersed than mammalian trade (ses.PD of 5.11 versus 2.68, respectively) [24]. This indicates that bird species in trade represent more evolutionarily distinct lineages than expected by chance.

Functional diversity in trade exhibits strong taxonomic and ecological bias. Large-bodied, frugivorous, and canopy-dwelling birds and large-bodied mammals are more likely to be traded, whereas insectivorous birds and diurnally foraging mammals are less likely to be traded [24]. This selective targeting of specific functional groups creates trait-based filters in traded wildlife communities, potentially disrupting critical ecological processes such as seed dispersal and nutrient cycling.

Table 2: Functional Traits Disproportionately Affected by Wildlife Trade

| Taxon | Traits with Increased Trade Likelihood | Traits with Decreased Trade Likelihood | Potential Ecosystem Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Large body size, frugivorous diet, canopy-dwelling | Insectivorous diet | Disruption of seed dispersal networks, reduced pest control |

| Mammals | Large body size | Diurnal foraging | Altered herbivory patterns, reduced seed dispersal |

Mechanisms: Why the Tropics Concentrate Traded PD and FD

Evolutionary and Ecological Foundations

Tropical regions serve as both museums and cradles of biodiversity, accumulating ancient lineages while maintaining high speciation rates. American tropical forests exhibit approximately 40% greater functional richness than African and Asian forests, while African forests show the highest functional divergence—32% and 7% higher than American and Asian forests, respectively [25]. This variation in functional composition creates distinct ecological portfolios across tropical regions, with different portions of total functional trait space occupied by American, African, and Asian forests.

The exceptional species richness of tropical regions provides the fundamental substrate for high PD and FD in trade. However, the disproportionate concentration of traded PD and FD stems from additional factors:

Evolutionary distinctness: Tropical regions harbor higher concentrations of evolutionarily distinct species—those isolated on phylogenetic trees—which are often targeted for their unique characteristics [24]. These species frequently possess distinctive morphological, behavioral, or aesthetic traits that increase their trade desirability.

Functional distinctness: The same traits that make species ecologically distinctive may also increase their appeal for various forms of trade. For example, the helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) possesses a unique "red-ivory" casque that has made it a high-value commodity in international markets [24].

Socioeconomic Drivers and Selection Biases

Market dynamics interact with biological patterns to shape the geography of traded PD and FD. Several mechanisms drive the concentration of trade in tropical regions:

International demand patterns: High-value international markets target tropical species for pets, traditional medicine, and luxury goods. For instance, most avian PD is traded as pets whereas most mammalian PD is traded as products, with regional variations in these patterns [24].

Rural subsistence and local use: High volumes of wildlife are traded in rural communities of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, where pervasive subsistence use targets many species, contributing to high traded PD [24]. For example, 112 bird species have been recorded as cagebirds in Java, Indonesia, and over 350 bird species spanning 70 families are used in traditional medicine markets in sub-Saharan Africa [24].

Hyperdiversity as driver and consequence: The underlying hyperdiversity of tropical regions shapes trade patterns, with areas of high overall PD and FD naturally containing more potential trade species. Simultaneously, trade itself can exacerbate biodiversity loss in these regions, creating a feedback loop that further concentrates impacts on unique evolutionary lineages and ecological functions.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Assessing PD and FD

Field Sampling and Data Collection Protocols

Research on traded PD and FD employs standardized methodologies across biological and socioeconomic domains. The following experimental protocols represent best practices in the field:

Protocol 1: Assessing Biodiversity Impacts of Land-Use Change

- Application: Quantifying impacts of habitat conversion on biodiversity across spatial scales [26]

- Sampling Design: Matched-point surveys across natural habitat (forest) and converted land (cattle pasture) across multiple biogeographic regions

- Data Collection: Standardized point counts with multiple visits across consecutive days; detection of all species within fixed radius (e.g., 100m)

- Statistical Analysis: Multi-species biogeographic occupancy modeling accounting for imperfect detection; prediction of species-specific responses to habitat conversion

- Scale Integration: Upscaling from local to regional impacts using hexagonal grids to examine beta-diversity effects

Protocol 2: Mapping Canopy Functional Traits

- Application: Predicting variation in functional traits across tropical forests [25]

- Field Data Collection: Vegetation census from permanent plots; measurement of 13 tree functional traits (morphological and chemical)

- Remote Sensing Integration: Sentinel-2 satellite data (2019-2022) including surface reflectance and derived vegetation indices (MCARI, MSAVI2, NDRE)

- Environmental Covariates: Soil texture/chemistry (SoilGrids), terrain (slope), climate (maximum water deficit, maximum temperature)

- Modeling Approach: Random forest models to predict community-weighted mean trait values; spatial block leave-one-out cross-validation to account for spatial autocorrelation

Analytical Frameworks for PD and FD Assessment

The computational analysis of phylogenetic and functional diversity involves specialized analytical workflows:

PD and FD Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated analytical framework for assessing traded phylogenetic and functional diversity, from data collection to conservation application.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PD/FD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Application in PD/FD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity Data | IUCN Red List, BirdLife International, PHYLACINE, EltonTraits | Species distributions, threat status, phylogenetic relationships, functional trait data |

| Trade Data | CITES Trade Database, IUCN SIS, national customs records | Documentation of legal wildlife trade volumes, routes, and species |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | V.PhyloMaker, U.Taxonstand, Phylogenetic trees from BirdTree.org | Construction and standardization of phylogenetic trees for PD calculations |

| Functional Trait Databases | TRY Plant Trait Database, GEM, ForestPlots.net, Frugivoria | Trait data for calculating functional diversity metrics |

| Spatial Analysis | R packages (betapart, SF, raster, sp), QGIS, SoilGrids, TerraClimate | Spatial mapping of PD/FD hotspots, environmental covariate analysis |

| Remote Sensing | Sentinel-2, MODIS, Landsat | Large-scale mapping of functional traits and habitat characteristics |

Conservation Implications and Future Directions

The concentration of traded PD and FD in tropical regions necessitates targeted conservation strategies that address both the supply and demand sides of wildlife trade. Current evidence suggests that strict protected areas do not always contain higher biodiversity levels than less strict ones [27], highlighting the importance of incorporating multiple biodiversity dimensions into conservation planning.

Community-managed lands have demonstrated particular effectiveness in protecting functional diversity [27], suggesting that empowering local communities may be a crucial strategy for safeguarding both phylogenetic and functional dimensions of biodiversity. Furthermore, systematic conservation planning that explicitly incorporates PD and FD—rather than relying solely on taxonomic diversity—can help ensure the protection of evolutionary history and ecosystem function.

Future research priorities include:

- Expanding assessments to underrepresented taxonomic groups (reptiles, amphibians, plants, invertebrates)

- Integrating illegal trade data into PD and FD assessments

- Developing dynamic monitoring systems that track temporal changes in traded PD and FD

- Evaluating the effectiveness of different conservation interventions in protecting phylogenetic and functional dimensions of biodiversity

As global conservation aims to protect 30% of Earth's land by 2030 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, prioritizing areas with high traded PD and FD could maximize the conservation of evolutionary history and ecological functions threatened by wildlife trade.

Measuring and Applying Diversity Metrics in Conservation

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Comparative Framework for Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics

- In-Depth Metric Analysis and Protocols

- The Phylogenetic Gambit: PD as a Surrogate for Functional Diversity

- Essential Research Toolkit

Phylogenetic diversity (PD) provides a critical evolutionary perspective for biodiversity science and conservation, moving beyond simple species counts to capture the richness of evolutionary history. Within a comparative analysis of phylogenetic versus functional diversity, specific PD metrics are essential for quantifying different dimensions of this history. This guide provides a detailed comparison of three foundational PD metrics—Faith's PD, Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD), and the EDGE index—which serve distinct purposes and capture different aspects of the phylogenetic tree [28]. Faith's PD measures the total branch length spanned by a set of taxa, representing the breadth of evolutionary history [1]. MPD calculates the average phylogenetic distance between all pairs of species in a community, reflecting the overall divergence within an assemblage [28]. The EDGE index integrates evolutionary distinctiveness with global endangerment to prioritize conservation efforts for unique and threatened lineages [1]. Understanding the specific applications, strengths, and limitations of these metrics is fundamental for designing robust conservation strategies and testing the central hypothesis that phylogenetic diversity serves as a reliable proxy for functional diversity in ecological systems.

Comparative Framework for Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics

A unified framework classifies phylogenetic diversity metrics into three core dimensions based on their mathematical underpinnings and the aspect of the phylogenetic tree they emphasize: richness, divergence, and regularity [28]. This classification provides a powerful lens for understanding the ecological questions each metric is best suited to answer.

Figure 1: A framework for phylogenetic diversity metrics, showing how core dimensions give rise to specific metrics and their conservation applications. The EDGE index is a composite metric that builds upon the principles of evolutionary distinctiveness, which is related to the richness dimension.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and limitations of the three key metrics within this framework.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics

| Feature | Faith's PD | Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD) | EDGE Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Sum of branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree spanned by a set of species [1]. | Mean phylogenetic distance between all pairs of species in a community [28]. | Integrates Evolutionary Distinctiveness (ED) with Global Endangerment (GE) [1]. |

| Primary Dimension | Richness | Divergence | Conservation Priority (applied richness) |

| Typical Units | Substitutions per site (if based on molecular sequence data) or time [29]. | Same as branch length units (time or substitutions/site). | Dimensionless, weighted score. |

| Key Strengths | Simple, intuitive, directly represents the total amount of independent evolutionary history [30]. Sensitive to the addition or loss of deep branches. | Provides a measure of the overall phylogenetic relatedness in a community. Less sensitive to outlier species than Faith's PD. | Explicitly incorporates extinction risk, providing a direct and actionable conservation priority score [1]. |

| Key Limitations | Does not consider the distribution of distances between taxa. Can be insensitive to the loss of a single, unique species if the rest of the tree remains. | Can be overly influenced by deep evolutionary splits. Does not directly reflect the feature diversity represented by a set of species. | Relies on accurate and up-to-date extinction risk assessments (e.g., IUCN Red List). Does not directly account for complementarity between species. |

| Best-Suited For | Conservation Prioritization: Identifying sets of species or areas that maximize represented evolutionary history [1].Ecology: Measuring the phylogenetic breadth of a community. | Community Ecology: Inferring assembly rules (e.g., clustering vs. overdispersion) [28] [5].Macroecology: Studying broad-scale diversity patterns. | Species-Targeted Conservation: Prioritizing individual species for conservation action, as in the EDGE of Existence program [1] [10]. |

In-Depth Metric Analysis and Protocols

Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity (PD)

Faith's PD is a "richness" metric, quantifying the total amount of evolutionary history contained in a set of species by summing the lengths of all phylogenetic branches connecting the set of species to the root of the tree [1]. Its fundamental premise is that this cumulative branch length serves as a proxy for the total "feature diversity" of the set, capturing both known and unknown traits that may hold future value for humanity, known as "option value" [1] [30].

Experimental Protocol for Calculating Faith's PD: The standard computational approach involves a post-order tree traversal. However, with the growth of large datasets (e.g., microbiome studies with millions of features), efficient algorithms like Stacked Faith's PD (SFPhD) have been developed [31].

Figure 2: The core workflow for calculating Faith's PD, which involves pruning a phylogenetic tree to a set of species and summing the remaining branch lengths.

Key Workflow Considerations:

- Tree Requirements: The phylogenetic tree must be rooted and have meaningful branch lengths. Branch lengths typically represent time or the number of molecular substitutions per site [29].

- Computational Efficiency: For large trees, the SFPhD algorithm uses sparse matrix representations and partial aggregation during tree traversal to drastically reduce memory usage from O(nk) to O(n log[k]), where n is the number of samples and k is the number of vertices in the tree [31].

- Software Implementation: Faith's PD is widely implemented in bioinformatics packages. The SFPhD algorithm, for instance, is available in the

unifraclibrary [31].

Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD)

MPD is a "divergence" metric that quantifies the average phylogenetic relatedness between all possible pairs of species in a sample or community [28]. It provides an overall measure of phylogenetic dispersion.

Experimental Protocol for Calculating MPD: The calculation involves computing the phylogenetic distance for every possible pair of species in the community and then taking the mean. The distance between two species is calculated as the sum of the branch lengths along the path connecting them on the phylogenetic tree.

Table 2: MPD Calculation Steps and Formulae

| Step | Action | Formula/Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Construct Pairwise Distance Matrix | For a community with S species, create an S x S matrix where each element dᵢⱼ is the phylogenetic distance between species i and j. |

| 2. | Calculate Mean | ( MPD = \frac{2}{S(S-1)} \sum{i=1}^{S-1} \sum{j=i+1}^{S} d_{ij} ) This is the mean of all the pairwise distances in the upper triangle of the matrix. |

| 3. | Interpretation | High MPD indicates a community of distantly related species (phylogenetic overdispersion). Low MPD indicates a community of closely related species (phylogenetic clustering). |

Standardization via Null Models: In community ecology, the raw MPD value is often compared to a distribution of MPD values from null models (e.g., random shuffling of species labels across the tips of the phylogeny) to generate a standardized effect size, such as the Net Relatedness Index (NRI) [5]. This helps determine if the observed community is significantly more clustered or overdispersed than expected by chance.

The EDGE Index

The EDGE index is designed specifically for conservation prioritization. It ranks species based on their combined Evolutionary Distinctiveness (ED) and Global Endangerment (GE), helping to direct resources toward species that represent unique evolutionary history and face a high risk of extinction [1].

Experimental Protocol for Calculating the EDGE Index: The calculation is a two-step process that first determines a species' Evolutionary Distinctiveness and then combines it with its extinction probability.

Figure 3: The workflow for calculating the EDGE index, which integrates a species' unique evolutionary history with its imminent threat of extinction to generate a conservation priority score.

Key Workflow Considerations:

- Evolutionary Distinctiveness (ED): A species' ED is high if it has few close relatives, meaning it represents a long, unbranched lineage on the tree of life. It is calculated as the sum of the branch lengths from the species to the root, where each branch length is divided by the number of species descending from it [1].

- Global Endangerment (GE): This component uses data from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The GE score is derived from the estimated extinction probability associated with a species' Red List category (e.g., Critically Endangered, Endangered) [1].

The Phylogenetic Gambit: PD as a Surrogate for Functional Diversity

A central thesis in conservation is the "phylogenetic gambit"—the hypothesis that maximizing phylogenetic diversity (PD) will also maximize functional diversity (FD), thereby preserving a wider range of ecological traits and functions, including those yet unmeasured [10]. This is predicated on the assumption that traits evolve in a manner that creates phylogenetic signal (i.e., closely related species are more functionally similar than distant relatives).

Empirical Evidence and Limitations: Large-scale empirical tests across over 15,000 vertebrate species reveal that this gambit is a potentially risky strategy. While maximizing PD captures, on average, 18% more FD than selecting species at random, this positive average surrogacy is not reliable in all cases [10]. Alarmingly, in more than one-third of comparisons, maximizing PD captured less FD than a random selection of species. The reliability of PD as a surrogate for FD decreases in species-rich assemblages, where high functional redundancy means that a random selection of species may perform as well as, or better than, a PD-maximizing strategy [10].

Conservation Implications: These findings suggest that while PD-based prioritization (using metrics like Faith's PD or EDGE) is generally better than ignoring phylogeny, it is not a perfect substitute for FD-based conservation. The optimal strategy depends on data availability and conservation goals:

- When comprehensive trait data are available, FD metrics should be prioritized to directly secure ecological functions.

- When trait data are limited, PD metrics provide a useful, though imperfect, proxy that is generally superior to random selection or taxonomy-free approaches.

- A combined approach, using PD for broad-scale planning supplemented with FD data for critical groups, may offer the most robust path forward.

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rooted Phylogenetic Tree | Data | The foundational input for all calculations; branch lengths represent evolutionary time or change. | Essential for Faith's PD, MPD, and EDGE. The tree must be rooted and have meaningful branch lengths. |

| Species Occurrence/Abundance Matrix | Data | A table recording the presence/absence or abundance of species across different sites or communities. | Required for calculating site-specific Faith's PD and community-level MPD. |

| IUCN Red List Categories | Data | The global standard for assessing species' extinction risk (e.g., Critically Endangered, Vulnerable). | Critical for calculating the GE (Global Endangerment) component of the EDGE index. |

| V.PhyloMaker (R package) | Software | Generates a phylogeny for a given list of plant species using a mega-tree backbone [32]. | Useful for obtaining a phylogeny when one is not available, enabling PD calculations for plant communities. |

| Picante / Vegan (R packages) | Software | Comprehensive toolkits for integrating analyses of phylogenies and ecology. | Calculate Faith's PD, MPD, MNTD, and perform null model analyses for standardizing metrics (e.g., NRI, NTI). |

| Unifrac (Python/C library) | Software | A highly optimized library for calculating phylogenetic diversity metrics, including Faith's PD. | Implements the efficient SFPhD algorithm for large datasets (e.g., microbiome data with millions of features) [31]. |

| NEON Data | Data | The National Ecological Observatory Network provides open-source ecological data, including species inventories. | A source of standardized community data for testing ecological hypotheses with PD metrics [32]. |

| Egfr T790M/L858R/ack1-IN-1 | Egfr T790M/L858R/ack1-IN-1, MF:C22H20ClN7O, MW:433.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Bicalutamide-d5 | Bicalutamide-d5, MF:C18H14F4N2O4S, MW:435.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Functional diversity (FD) quantifies the range and distribution of functional traits in an ecological community, providing critical insights into ecosystem functioning, stability, and resilience beyond what species richness alone can reveal [33]. While numerous metrics exist to quantify FD, three have emerged as fundamental components representing distinct facets of the functional trait space: Functional Richness (FRic), Functional Evenness (FEve), and Functional Dispersion (FDis). These metrics help ecologists understand how environmental filters, competitive interactions, and stochastic processes shape biological communities [34]. Within conservation research, analyzing these functional components provides a more nuanced understanding of biodiversity's role in maintaining ecosystem processes compared to relying solely on phylogenetic diversity measures [10] [8].

This guide objectively compares these key FD metrics, detailing their ecological interpretations, methodological applications, and performance across different research contexts, with a specific focus on their value relative to phylogenetic diversity approaches in conservation science.

Metric Comparison & Experimental Data

Table 1: Core Functional Diversity Metrics Comparison

| Metric | Ecological Interpretation | Mathematical Basis | Response to Environmental Stress | Relationship to Species Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRic | Volume of functional space occupied; range of functional roles [33] | Convex hull volume in trait space [33] | Decreases under harsh conditions due to environmental filtering [34] | Strong positive correlation [35] |

| FEve | Regularity of abundance distribution in trait space; completeness of resource use [33] | Regularity of spacing in trait combinations [33] | Varies context-dependently; may decrease with stress [36] | Weak or negative correlation [35] |

| FDis | Mean distance of species to centroid of trait space; trait divergence/convergence [34] | Mean distance to weighted centroid in multivariate space [34] | Increases from high to low stress environments [34] | Variable correlation; often independent [35] |

Table 2: Empirical Patterns from Experimental Studies

| Study System | FRic Pattern | FEve Pattern | FDis Pattern | Key Driver Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rocky Intertidal Communities [34] | Increased from high to low intertidal (persistent across sites) | Not reported | Increased from high to low intertidal (context-dependent across sites) | Environmental filtering (desiccation stress) |

| Arid Plant Communities [36] | No clear pattern along aridity gradient | No clear pattern along aridity gradient | Mostly random patterns along gradient | Environmental heterogeneity at patch scale |

| Nested Plant Plots [35] | Strong positive correlation with area (z: 0.63-1.63) | Negative correlation with area | Weak or no correlation with area | Area and species accumulation |

| Bat Communities [37] | Higher in conserved areas vs. anthropic areas | Not reported | Not reported | Habitat degradation and fragmentation |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for FD Calculation

The diagram below illustrates the generalized experimental protocol for calculating functional diversity metrics from raw data to final interpretation:

Key Methodological Considerations

Trait Selection and Measurement: The accuracy of functional diversity assessments critically depends on selecting ecologically relevant traits that influence both organism fitness and ecosystem functioning [37] [33]. Studies should incorporate traits from both above-ground and below-ground organs where applicable, as different assembly processes can operate on different trait sets [36]. For bat communities, relevant traits include dietary preferences, foraging behaviors, shelter uses, and morphological measurements [37].

Data Processing Protocols: For homogeneous trait data (all traits measured on the same scale with no missing values), researchers can proceed directly to constructing a species × trait matrix. For heterogeneous data (mixed measurement scales with missing values), appropriate standardization procedures and resemblance coefficients must be selected based on data characteristics [33].

Statistical Controls: To isolate the "pure" effects of functional diversity independent of species richness, researchers should contrast FD metrics against null models or matrix-swap randomizations [34]. This is particularly important for FDis, which can be confounded by species richness effects if not properly controlled.

Functional vs. Phylogenetic Diversity in Conservation

The Phylogenetic Gambit Test

A fundamental assumption in conservation biology has been that maximizing phylogenetic diversity (PD) indirectly protects functional diversity—a hypothesis termed the "phylogenetic gambit" [10]. Empirical testing of this hypothesis using trait data from >15,000 vertebrate species reveals that:

- Maximizing PD captures 18% more FD on average than random species selection

- However, this strategy is unreliable—in 36% of comparisons, PD-maximized sets contained less FD than randomly chosen species sets

- The surrogacy of PD for FD weakens as species pool richness increases [10]

Context-Dependent Performance

Table 3: Comparative Performance in Detecting Anthropogenic Impacts

| Ecosystem Type | Taxonomic Diversity | Phylogenetic Diversity | Functional Diversity | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| River Ecosystems (Macroinvertebrates) | Decreased seasonally in both dammed and undammed rivers | Decreased only in undammed river with natural flow | Decreased only in undammed river with natural flow | [8] |

| Bat Communities (Pantanal & Cerrado) | Lower in anthropic areas | Higher in conservation units | Higher in conservation units (FRic) | [37] |

| Wetland Birds (Anatidae) | Declined without significant trends | ses.MPD declined dramatically (1950s-2010s) | FRic and body mass dispersion declined | [38] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in FD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Field Equipment | Mist nets (bat studies), point count equipment (bird studies), quadrats (plant studies) | Standardized organism sampling across treatments or gradients [37] [38] |

| Trait Measurement Tools | Calipers, drying ovens, leaf area meters, root scanners, stable isotope analyzers | Quantifying morphological, physiological, and chemical traits [36] |

| Statistical Software & Packages | R packages: FD, vegan, picante, phyloregion; BEAST 2 (phylogenetics) | Calculating FD indices, phylogenetic analyses, null model testing [37] [38] |

| Data Resources | BirdTree, TRY Plant Trait Database, phylogenetic trees from published literature | Accessing phylogenetic and trait data for comparative analyses [10] [38] |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | GIS software, GPS units, remote sensing data (e.g., MODIS) | Characterizing environmental gradients and spatial patterns [34] |

| Ac-LEVD-PNA | Ac-LEVD-pNA|Caspase-4 Substrate | Ac-LEVD-pNA is a chromogenic caspase-4 substrate for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or diagnostic use. |

Functional Richness (FRic), Functional Evenness (FEve), and Functional Dispersion (FDis) provide complementary and non-redundant information about different aspects of ecological communities. FRic captures the range of functional traits, FEve quantifies the regularity of trait distribution, and FDis measures trait divergence/convergence patterns. Each metric responds differently to environmental gradients, anthropogenic disturbances, and spatial scales, making them collectively valuable for understanding community assembly mechanisms.

For conservation applications, functional diversity metrics often detect anthropogenic impacts more sensitively than taxonomic diversity alone [8] [37]. While phylogenetic diversity provides valuable evolutionary context, it serves as an unreliable proxy for functional diversity, with the "phylogenetic gambit" failing in over one-third of cases [10]. An integrated approach that combines taxonomic, phylogenetic, and multiple functional diversity dimensions offers the most comprehensive framework for conservation prioritization and ecosystem management.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of key software and spatial analysis frameworks used in conservation research, focusing on the study of phylogenetic diversity (PD) and its relationship to functional traits.

Software for Phylogenetic and Biodiversity Analysis

The table below summarizes the primary purpose and key application of major analytical tools.

| Software/Framework | Primary Purpose & Analysis Type | Key Application in Conservation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Picante (R Package) [22] | Analysis of phylogenetic and trait diversity within communities [22]. | Integrating PD with community ecology to test hypotheses on diversity patterns [22]. |

| Biodiverse (Desktop GUI) [39] | Spatial analysis of biodiversity based on species distributions [39]. | Calculating PD, endemism, and spatial planning to maximize protected evolutionary history [39]. |

| CANAPE (Framework) [39] | Identifying centers of neo- and paleo-endemism via spatial phylogenetics [39]. | Conserving the full evolutionary spectrum, including recent diversification hotspots [39]. |

Comparative Analysis of Capabilities and Performance

Key Differentiators and Conservation Applications

Each tool addresses a distinct niche in the conservation research pipeline.

Picante: Integrating Ecology and Phylogeny Picante is an R package designed for analyzing phylogenetic and trait data in the context of ecological communities [22]. Its strength lies in testing specific hypotheses, such as whether PD is a reliable proxy for functional diversity (FD). Research indicates that while PD is advocated as a proxy for broad "feature diversity," its performance in capturing narrowly defined FD can be variable, highlighting the importance of tool-based validation [22].

Biodiverse: Spatial Conservation Planning Biodiverse is a standalone application with a graphical interface for spatial analysis [39]. It directly supports systematic conservation planning by calculating key metrics like PD and phylogenetic endemism (PE) across a landscape. A study on Mantellid frogs in Madagascar used Biodiverse to identify priority areas that maximize the capture of PD within a protected area network [39].

CANAPE: Uncovering Evolutionary Hotspots The Categorical Analysis of Neo- and Paleo-Endemism (CANAPE) is not a software product but an analytical framework, often implemented within platforms like Biodiverse [39]. It identifies significant centers of endemism by distinguishing areas rich in ancient, unique evolutionary history (paleo-endemism) from areas with high concentrations of recently diverged species (neo-endemism). This allows conservation strategies to protect not just evolutionary history but also active evolutionary processes [39].

Critical Considerations from Empirical Evidence

The PD-FD Relationship: A core rationale for using PD-based tools like Picante is that evolutionary history captures functional trait diversity. However, empirical evidence is mixed. Some studies conclude that PD captures FD "unreliably," while others argue that PD represents a broader "feature diversity" beyond a few measured traits, which is critical for future options and ecosystem resilience [22].

Efficiency in Conservation Planning: Research demonstrates that targeting PD alone may overlook crucial centers of neo-endemism [39]. In the Mantellid frog study, a business-as-usual approach targeting only taxonomic diversity and PD failed to adequately protect areas with high concentrations of recently evolved species. Explicitly targeting centers of endemism identified by CANAPE provided a more cost-effective strategy for conserving the entire evolutionary spectrum [39].

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

The following workflow outlines a standard methodology for applying and comparing these tools in a conservation context.

Standard Workflow for Comparative Analysis of Biodiversity Tools

Data Acquisition and Curation

- Species Data: Collect a comprehensive species occurrence dataset for the target taxonomic group (e.g., Mantellid frogs) and geographic region (e.g., Madagascar). Data should include both formally described and candidate species where possible to minimize diversity underestimation [39].

- Phylogenetic Tree: Obtain a robust, time-calibrated molecular phylogeny that includes all study species. Branch lengths should represent evolutionary time or genetic divergence [39].

- Environmental & Spatial Data: Compile relevant GIS layers, which may include current protected area boundaries, land use, and climate data to inform the spatial prioritization context [39].

Analytical Procedures

- Metric Calculation with Biodiverse: Grid the study area into a uniform resolution. For each grid cell, calculate Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) and Phylogenetic Endemism (PE), which weights branch lengths by the restricted range of descendant species [39].

- CANAPE Execution: Implement the CANAPE framework within Biodiverse. This involves:

- Calculating standardized effect sizes for PD and PE via spatial randomizations.

- Categorizing grid cells into statistically significant centers of: paleo-endemism (ancient, unique history), neo-endemism (recent radiations), mixed-endemism, or super-endemism (exceptionally high endemism) [39].

- Community-Level Analysis with Picante: In R, use

picanteto integrate the phylogeny and species presence-absence data for each site or grid cell. Calculate complementary metrics like Faith's PD and, if trait data is available, compare these with measures of Functional Diversity (FD) to test their correlation [22].

Conservation Prioritization Experiment

- Define Scenarios: Use spatial prioritization software to run different conservation scenarios [39]:

- Scenario Tx: Target taxonomic diversity (species distributions) only.

- Scenario Br: Target both taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity.

- Scenario BrCE: Explicitly target the centers of endemism identified by CANAPE.

- Evaluate Performance: For each scenario, measure the proportion of total PD and the proportion of each endemism type (neo-, paleo-, mixed-) secured within the prioritized areas. This quantifies how effectively each strategy captures different facets of evolutionary diversity [39].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key computational and data "reagents" essential for conducting this analysis.

| Research Reagent | Function / Rationale | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Calibrated Phylogeny | Backbone for all PD-based calculations; branch lengths in millions of years are critical for interpreting evolutionary patterns [39]. | Used in Biodiverse to calculate Phylogenetic Endemism and in Picante to calculate Faith's PD [39]. |

| Species Occurrence Grids | Spatial matrix linking species to specific locations; the fundamental unit for calculating spatial diversity metrics [39]. | Input for Biodiverse to map species richness, PD, and endemism across a landscape [39]. |

| Spatial Prioritization Software | Algorithmically identifies optimal sets of areas to meet quantitative conservation targets efficiently [39]. | Used to compare the performance of different conservation scenarios (Tx, Br, BrCE) in protecting evolutionary history [39]. |

| Functional Trait Database | Curated dataset of species' morphological/ecological traits to calculate Functional Diversity (FD) for comparison with PD [22]. | Used with Picante to test the empirical link between phylogenetic history and functional traits [22]. |

In the face of escalating biodiversity declines, conservation biology has increasingly relied on evidence-based approaches to prioritize protection efforts. This comparative analysis examines two fundamental frameworks in conservation planning: the use of phylogenetic diversity (PD) versus functional diversity (FD) for identifying global conservation priorities, and the persistent SLOSS debate (Single Large or Several Small reserves) in habitat fragmentation contexts. Conservation triage decisions have profound implications for resource allocation, reserve design, and ultimately, species persistence. Researchers and conservation professionals must navigate complex trade-offs when selecting surrogate measures for overall biodiversity, with phylogenetic diversity representing evolutionary history and functional diversity capturing the variety of ecological roles within ecosystems. Meanwhile, the SLOSS debate addresses one of conservation's most fundamental spatial questions: whether to consolidate conservation resources into single large reserves or distribute them across several smaller patches. This article provides a systematic comparison of these approaches through quantitative data synthesis, methodological protocols, and visual frameworks to guide conservation decision-making.

Phylogenetic vs. Functional Diversity: Theoretical Foundations and Conservation Rationale

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Phylogenetic diversity (PD) quantifies the breadth of evolutionary history represented by a set of species, typically calculated as the sum of branch lengths connecting species on a phylogeny. The underlying conservation hypothesis, termed the "phylogenetic gambit," assumes that maximizing PD will indirectly capture functional and trait diversity because species traits reflect shared evolutionary history [10]. In contrast, functional diversity (FD) measures the variety of ecological functions performed by organisms within an ecosystem, based on morphological, physiological, or behavioral traits that influence organism performance or ecosystem functioning. FD can be decomposed into multiple components: functional richness (the volume of functional space occupied), functional divergence (deviation of abundance from the center of gravity in functional space), and functional regularity (the regularity of distribution in functional space) [33].

Comparative Performance in Conservation Contexts

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity in Conservation Planning

| Metric | Data Requirements | Conservation Rationale | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) | Molecular data for robust phylogenies, taxonomic information | Preserves evolutionary history, potential proxy for unmeasured traits | Provides measurable conservation target (EDGE program), integrates evolutionary distinctiveness | Weak correlation with FD in many clades, can miss ecologically significant species |

| Functional Diversity (FD) | Species trait data (morphological, physiological, ecological) | Directly captures ecosystem functions and services | Stronger link to ecosystem functioning, measurable mechanistic relationships | Trait data availability limited, measurement standardization challenges |

Empirical evidence reveals significant limitations in the assumed PD-FD relationship. A comprehensive analysis of >15,000 vertebrate species found that while maximizing PD results in an average gain of 18% of FD relative to random species selection, this strategy fails in over one-third of cases, where PD-maximized sets contain less FD than randomly chosen sets [10]. This suggests that while PD protection can help protect FD, it represents a risky conservation strategy when used alone. More recently, a global analysis of 1.7 million vegetation plots demonstrated only a weak and negative correlation between standardized effect sizes for FD and PD, indicating a widespread decoupling between these diversity facets in plant communities [40].

Quantitative Comparison: Empirical Evidence Across Taxa and Ecosystems

Table 2: Empirical Comparisons of Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity Across Studies

| Study System | Sample Size | PD-FD Correlation | Key Findings | Conservation Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Vertebrates [10] | 15,000+ species | Variable (surrogacy: -85% to +92%) | PD maximizes FD in only 64% of trials; weaker surrogacy in species-rich pools | PD unreliable as sole conservation criterion; context-dependent utility |

| Global Plants [40] | 1,781,836 plots | Weak negative correlation | FD reflects recent and past climate (21k years); PD reflects only recent climate | Independent consideration of both facets essential for conservation |