Picocyanobacteria as Estuarine Carbon Engineers: Unveiling Their Critical Role in Carbon Fixation and Ecosystem Dynamics

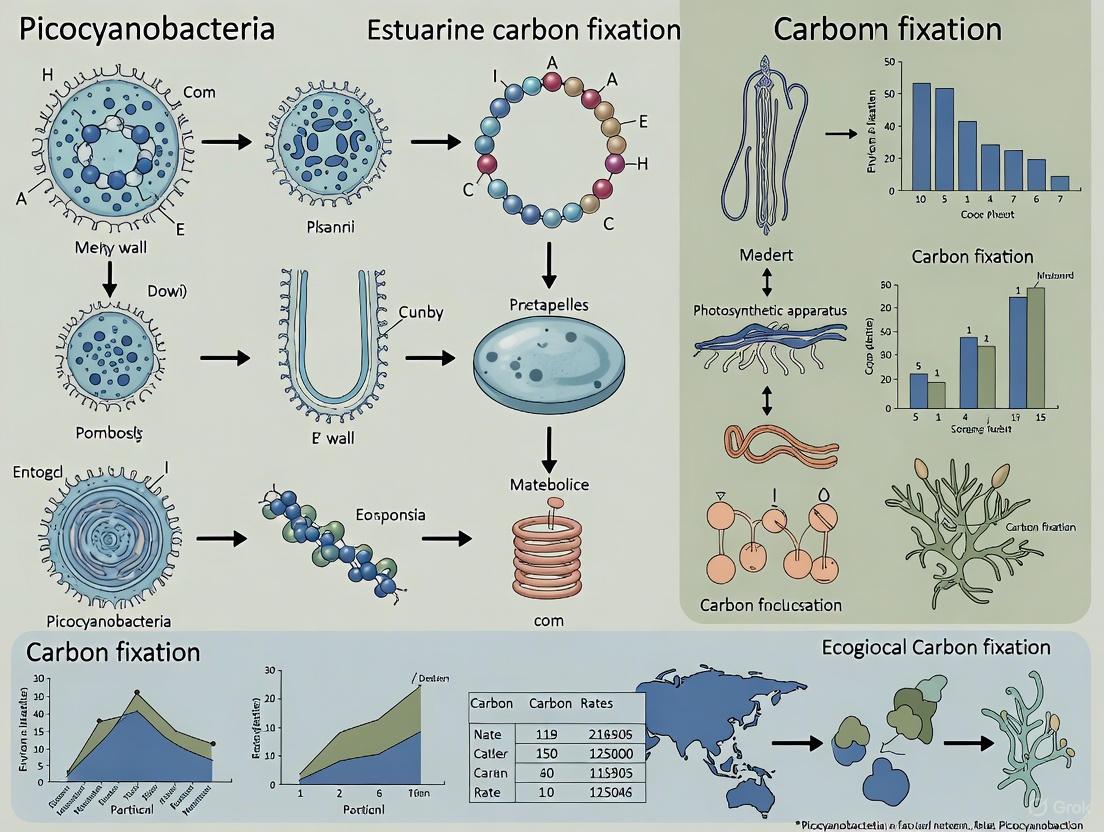

This article synthesizes current research on the pivotal role of picocyanobacteria in estuarine carbon fixation, a critical yet underexplored component of the global carbon cycle.

Picocyanobacteria as Estuarine Carbon Engineers: Unveiling Their Critical Role in Carbon Fixation and Ecosystem Dynamics

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the pivotal role of picocyanobacteria in estuarine carbon fixation, a critical yet underexplored component of the global carbon cycle. Targeting researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational ecology of these microorganisms, detailing their community composition and response to environmental gradients. The review advances to methodological frameworks for quantifying their biomass and productivity, examines their resilience to climatic and anthropogenic stressors, and validates their contribution through comparative carbon budget analyses. By integrating foundational knowledge with applied and comparative perspectives, this work aims to establish a refined understanding of picocyanobacteria as indispensable agents in estuarine carbon sequestration and ecosystem functioning, with implications for biogeochemical modeling and climate change research.

Unveiling the Estuarine Picocyanobacteria: Ecology, Diversity, and Environmental Drivers

Picocyanobacteria, the photosynthetic prokaryotes less than 2-3 micrometers in diameter, represent a critical component of estuarine microbial communities, functioning as significant contributors to carbon fixation and nutrient cycling. These microscopic organisms, primarily encompassing the genera Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, thrive in the dynamic transitional zones where freshwater and seawater mix. In estuarine environments characterized by pronounced physical and chemical gradients, picocyanobacteria demonstrate remarkable adaptability, with distinct populations exhibiting specific niche preferences and physiological capabilities. Their role in the microbial carbon pump and as foundational contributors to estuarine primary production positions them as essential players in carbon sequestration processes [1] [2]. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the diversity, distribution, and functional significance of picocyanobacteria within estuarine ecosystems, providing researchers with methodological frameworks and ecological insights relevant to carbon fixation research.

Diversity and Global Distribution Patterns

Estuarine systems host a remarkable phylogenetic diversity of picocyanobacteria that reflects their adaptive capacity across salinity, temperature, and nutrient gradients. Molecular analyses using 16S rRNA and Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing have revealed multiple distinct lineages with specific habitat preferences.

Major Phylogenetic Groups

Marine Synechococcus Subclusters: Estuarine environments typically harbor members of subclusters 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3, with subcluster 5.2 often dominating in colder, higher-latitude estuaries [3] [4]. Subcluster 5.1 represents a broadly adapted group found across marine-influenced zones, while subcluster 5.3 contains several novel clades preferentially found in subtropical open oceans and connected estuaries [3].

Freshwater and Brackish Lineages: The genera Cyanobium and freshwater Synechococcus frequently occur in upper estuarine regions influenced by riverine input, forming a continuum from freshwater to marine zones [2]. These populations often persist as a "core community" spanning salinity gradients, suggesting resilience to fluctuating conditions [5].

Prochlorococcus Ecotypes: While predominantly an open ocean genus, Prochlorococcus high-light (HL) adapted ecotypes (HLIII, HLIV, HLV) have been detected in equatorial Pacific samples and could be related to populations found in high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll (HNLC) tropical oceans [3]. However, their abundance typically decreases significantly in estuarine systems compared to oceanic waters.

Table 1: Quantitative Abundance of Picocyanobacteria in Global Estuarine Systems

| Location | Synechococcus (cells/L) | Prochlorococcus (cells/L) | Dominant Taxa | Sampling Period | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khatanga River Estuary (Russian Arctic) | 1.25 × 10ⶠ| Not detected | Subclusters 5.1-I, 5.2 | September 2017 | [4] |

| Kolyma River Estuary (Russian Arctic) | 1.58 × 10ⶠ| Not detected | Subclusters 5.1-I, 5.2 | September 2017 | [4] |

| Indigirka River Estuary (Russian Arctic) | 0.42 × 10ⶠ| Not detected | Subclusters 5.1-I, 5.2 | September 2017 | [4] |

| Yellow River Estuary (China) | 1.02 × 10ⶠ(AG), 0.85 × 10ⶠ(FL) | Not reported | Subcluster 5.1 (clades I and IV) | November 2022 | [1] |

| Chesapeake Bay (USA) | Seasonal variation 10âµ-10â· | Rare | Subcluster 5.2, Cyanobium | Multi-year | [2] |

| Albemarle Pamlico Estuary System (USA) | 72% of cyanobacterial sequences | Minimal | Subcluster 5.2, Synechocystis | 2017-2019 | [5] |

Biogeographical Controls

The global distribution of estuarine picocyanobacteria is governed primarily by temperature and salinity regimes. In the Arctic estuaries of Siberian rivers, Synechococcus subcluster 5.2 dominates, suggesting cold-adaptation of these specific lineages [4]. A distinct shift in picocyanobacterial communities was observed from the Bering Sea to the Chukchi Sea, reflecting changing water temperatures and highlighting the sensitivity of these organisms to thermal gradients [3]. Similarly, in the Kwangyang Bay estuary in Korea, Synechococcus composition varied significantly with season, with blooms occurring only in summer when water temperatures reached 24-26°C [6].

Methodologies for Community Analysis

Accurate characterization of estuarine picocyanobacterial communities requires integrated approaches combining cytometric enumeration with molecular techniques for genetic resolution.

Sample Collection and Preservation

- Water Collection: Conduct using Niskin-type bottles mounted on a CTD rosette system equipped with sensors for conductivity, temperature, depth, and chlorophyll fluorescence [4]. Collect surface water or samples from chlorophyll maximum layers.

- Preservation: For flow cytometry, fix samples with glutaraldehyde (0.1% final concentration) and freeze in liquid nitrogen for transport [7]. For DNA analysis, filter 0.5-1L water through 0.22-μm pore-size polycarbonate filters and store at -80°C until extraction.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

- Instrumentation: Use flow cytometers equipped with 488-nm and 640-nm laser sources. Measure forward scatter (FSC), side scatter (SSC), orange fluorescence (575±20 nm) from phycoerythrin, and red fluorescence (675±10 nm) from chlorophyll [4].

- Identification: Differentiate picocyanobacteria based on their signature pigment fluorescence: Synechococcus exhibits strong phycoerythrin fluorescence, while Prochlorococcus shows dimmer chlorophyll fluorescence [8]. Add 1-μm fluorescent microspheres as internal standards for quantification.

Molecular Characterization

- DNA Extraction: Use PowerWater DNA Isolation Kit or similar with modification of three freeze-thaw cycles prior to extraction to enhance cell lysis [5].

- 16S rRNA Amplification: Amplify the V3-V4 region (~379 bp) of the 16S rRNA gene using cyanobacteria-specific primers CYB359-F (5'-GGGGAATYTTCCGCAATGGG-3') and CYB781-R (5'-GACTACTGGGGTATCTAATCCCATT-3') with CS1 and CS2 linker sequences [5].

- ITS Region Analysis: For higher phylogenetic resolution, target the 16S-23S rRNA Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region using primers described in [3].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Employ Illumina MiSeq V3 chemistry (2 × 250 bp). Process sequences using DADA2 or similar pipeline for amplicon sequence variant (ASV) calling. Classify sequences against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) with taxonomic assignment confirmed via phylogenetic placement.

Picocyanobacteria Community Analysis Workflow

Ecological Functions and Carbon Export Mechanisms

Picocyanobacteria contribute significantly to estuarine carbon dynamics through both metabolic activities and physical transport processes, functioning as key intermediaries in the carbon cycle.

Primary Production and Biomass Contribution

In estuarine systems like the Albemarle Pamlico Sound, picocyanobacteria alongside picoeukaryotes contribute approximately 47% of total chlorophyll a, indicating their substantial role in photosynthetic biomass [5]. During seasonal blooms, this contribution can exceed 70% of summer phytoplankton biomass in subsystems such as the Neuse River Estuary [5]. Synechococcus alone contributes an estimated 16.7% to global marine net primary production, with even higher contributions possible in productive coastal regions [1].

Aggregation and Carbon Export

A significant fraction of estuarine Synechococcus exists in aggregating (AG) forms that contribute directly to particulate organic carbon (POC) export:

- Size Fractionation: In the Yellow River Estuary, 14.7-85.4% of Synechococcus populations were retained on 3-μm filters, indicating transition from free-living (FL) to aggregating (AG) lifestyles [1].

- Export Efficiency: AG Synechococcus correlated significantly with POC (R² = 0.69), contributing to sinking particulate fluxes [1]. These aggregates, reaching 1.4 mm diameter with ballasting minerals, can sink at speeds up to 440 m dâ»Â¹, comparable to diatom aggregates [1].

- Mineral Ballasting: Terrigenous sediments (particularly clay minerals) transported by rivers facilitate aggregation and sinking by acting as ballast, enhancing carbon export from euphotic zones [1].

Table 2: Carbon Export Parameters of Aggregating Synechococcus in Estuarine Systems

| Parameter | Free-Living (FL) Form | Aggregating (AG) Form | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size fraction | <3 μm | >3 μm | Filtration/Epifluorescence microscopy |

| Contribution to POC | Minimal | R²=0.69 with POC | Linear regression |

| Sinking speed | Negligible | Up to 440 m dâ»Â¹ | Laboratory measurements |

| Ballast minerals | Not associated | Clay, silicon, calcium compounds | Elemental analysis |

| Dominant lineages | Subcluster 5.1 (Clades I, IV) | Subcluster 5.1 (Clades I, IV) | 16S rRNA sequencing |

Dissolved Organic Matter Production

Picocyanobacteria significantly influence dissolved organic matter (DOM) pools through extracellular release:

- Autochthonous DOM: In the Yangtze Estuary, picocyanobacteria-dominated blooms produce protein-like fluorescent components that dominate the DOM pool [9]. During warmer seasons, high picocyanobacteria abundance correlates with increased dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations [9].

- Microbial Transformation: Picocyanobacterial-derived labile DOM undergoes rapid processing by heterotrophic bacteria, particularly Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, leading to transformation into more refractory compounds through the microbial carbon pump (MCP) [9].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Estuarine Picocyanobacteria Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | PowerWater DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) | Environmental DNA extraction from filters | Optimized for low-biomass water samples |

| PCR Amplification | KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix | 16S rRNA/ITS amplification | High fidelity for community sequencing |

| Cyanobacteria-Specific Primers | CYB359-F/CYB781-R (Nübel et al. 1997) | 16S rRNA amplification | Cyanobacterial-specific V3-V4 region |

| Flow Cytometry | BD Accuri C6, Guava EasyCyte HT | Cell enumeration and sizing | 488-nm and 640-nm lasers for pigment detection |

| Sequence Processing | DADA2 pipeline (R package) | Amplicon sequence variant analysis | High-resolution ASV calling from Illumina data |

| Cell Preservation | Glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde | Sample fixation for flow cytometry | Maintains optical properties for cytometric analysis |

| Size Fractionation | 3-μm polycarbonate filters | Separating free-living vs. aggregating cells | Determines lifestyle partitioning |

| Chlorophyll Analysis | Turner Designs Trilogy fluorometer | Chlorophyll a quantification | Sensitive detection of picophytoplankton pigments |

| Otophylloside H | Otophylloside H, MF:C60H90O27, MW:1243.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Gymnoside VII | Gymnoside VII, MF:C51H64O24, MW:1061.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Climate Change Vulnerabilities and Future Research

Understanding the responses of estuarine picocyanobacteria to climate change is crucial for predicting future carbon cycling dynamics.

Temperature Sensitivity

- Prochlorococcus Thermal Limits: Recent research reveals Prochlorococcus division rates increase exponentially to 28°C then sharply decline, with nearly threefold reduction by 31°C [7]. This suggests potential 17-51% production reductions in tropical oceans under future warming scenarios [7].

- Synechococcus Resilience: In contrast, Synechococcus abundances do not show similar declines at high temperatures, maintaining populations in waters above 28°C where Prochlorococcus decreases [7]. This differential response may favor Synechococcus in warming estuarine systems.

Adaptive Capacity

Estuarine picocyanobacteria demonstrate notable adaptive capabilities:

- Genetic Resilience: Chesapeake Bay isolates contain rich toxin-antitoxin (TA) gene systems, potentially providing genetic advantage in fluctuating estuarine conditions [2].

- Salinity Tolerance: Core communities of Synechococcus, Cyanobium, and Synechocystis persist across freshwater to polyhaline environments, indicating resilience to salinity fluctuations [5].

- Seasonal Succession: Distinct winter and summer populations in temperate estuaries suggest adaptive seasonal niche partitioning [2].

Climate Change Impacts on Estuarine Picocyanobacteria

Estuarine picocyanobacteria, particularly diverse lineages of Synechococcus and their picocyanobacterial relatives, represent crucial components of carbon fixation and transformation pathways in transitional waters. Their phylogenetic diversity, niche partitioning across environmental gradients, and dual roles in both primary production and carbon export processes underscore their significance in estuarine carbon budgets. The methodological frameworks outlined in this guide provide researchers with standardized approaches for quantifying their abundance, diversity, and ecological functions. As climate change continues to alter estuarine conditions, understanding the vulnerabilities and resilient capacities of these microbial communities becomes increasingly important for predicting carbon cycle feedbacks and managing estuarine ecosystem health. Future research should prioritize integrated molecular and biogeochemical approaches to elucidate the complex interactions between picocyanobacterial community structure and carbon sequestration functions across diverse estuarine systems.

Picocyanobacteria, the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth, are fundamental to estuarine carbon fixation, contributing significantly to global primary production and carbon cycling [10] [11] [12]. These microorganisms, primarily from the genera Synechococcus, Cyanobium, and Synechocystis, exhibit complex distribution patterns dictated by a suite of spatial and temporal environmental drivers [13] [14]. Understanding these dynamics is critical for predicting ecosystem responses to climate change and for managing estuarine health. This technical review synthesizes current research on the abundance patterns of picocyanobacteria across temperate, brackish, and tropical systems, detailing the methodologies for their study and their overarching role in the estuarine carbon cycle. The focus on estuarine systems is particularly pertinent, as they are dynamic transition zones where picocyanobacteria demonstrate remarkable physiological resilience to fluctuating conditions [13].

Global and Regional Spatial Patterns of Abundance

The distribution of picocyanobacteria is highly heterogeneous, shaped by large-scale oceanic gradients and localized estuarine conditions. Their abundance can vary by orders of magnitude across different marine regimes.

Table 1: Global Abundance Ranges of Picocyanobacteria in Different Systems

| System Type | Example Location | Reported Abundance | Dominant Genera | Key Environmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperate Coastal | Northern California Current (NCC), USA | Higher in summer; increases with distance from shore [15] | Synechococcus spp., PPE | Dynamic coastal currents, intermittent upwelling, seasonal marine heatwaves |

| Brackish Sea | Baltic Sea | Up to 10âµ cells mLâ»Â¹; ~21-56% of phytoplankton biomass [14] | S5.2 Clade, Clade A/B | Salinity gradient (2.9-22 PSU), summer nitrogen limitation, temperature stratification |

| Large Estuary | Albemarle-Pamlico Sound System (APES), USA | 72% of cyanobacterial amplicon sequences [13] | Synechococcus (55.4%), Cyanobium (14.8%), Synechocystis (12.9%) | Resilience to salinity fluctuations; core community across freshwater to polyhaline regions |

| Tropical/Subtropical | Oligotrophic Open Ocean | Global average of ~10â´-10âµ cells mLâ»Â¹; dominates primary production [16] [12] | Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus | Stable stratification, high temperatures, low nutrient concentrations |

Spatial patterns are evident across onshore-offshore transects. In the Northern California Current system, abundances of both picocyanobacteria and photosynthetic picoeukaryotes (PPE) consistently increase with distance from shore [15]. This pattern is linked to the transition from nutrient-rich, turbid coastal waters to more stable, oligotrophic offshore waters. Furthermore, the coastal bathymetry influences these distributions; wide, gently sloping continental shelves (as found in northern transects) present different habitats compared to steep, narrow shelves (southern transects), affecting water flow and community structure [15].

A key spatial driver is salinity, which structures picocyanobacterial communities along estuarine gradients. In the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound System, a "core community" of picocyanobacteria, including Synechococcus, Cyanobium, and Synechocystis, persists across a wide salinity range from oligohaline to polyhaline waters [13]. This suggests significant resilience to salinity fluctuations. However, finer-scale genetic analysis reveals the presence of distinct putative ecotypes with specific abundance patterns along the salinity gradient, highlighting substantial fitness variability among closely related populations [13].

Table 2: Key Environmental Drivers of Picocyanobacterial Spatial Distribution

| Driver | Effect on Picocyanobacteria | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Salinity Gradient | Structures community composition; selects for resilient core taxa and specific ecotypes [13] | APES core community spanning freshwater to polyhaline regions [13] |

| Distance from Shore | Abundance typically increases offshore; community shifts from PC-rich to PE-rich types [15] [14] | NCC offshore stations show higher picocyanobacteria counts [15] |

| Nutrient Availability | Thrive in low-nutrient conditions, especially when Nitrogen is limited; outcompete larger phytoplankton [14] [17] | Baltic Sea blooms under summer nitrogen limitation [14] |

| Water Mass Stratification | Favors picocyanobacteria over larger phytoplankton; linked to dominance of specific clades [14] | S5.2 clade dominance in stratified Baltic Sea summers [14] |

Seasonal and Event-Driven Temporal Dynamics

Picocyanobacterial populations exhibit pronounced seasonal cycles and respond rapidly to short-term climatic events, making their temporal dynamics a critical aspect of their ecology.

The most robust seasonal signal is the dramatic increase in abundance during summer months. In the Baltic Sea, picocyanobacterial cell numbers correlate positively with temperature and negatively with nitrate concentration, leading to peak blooms in the warm, nitrogen-limited summer season [14]. Similarly, in the Northern California Current, picocyanobacteria are "much more abundant in the summer than the winter" [15]. This summer peak is not merely a numerical increase but also involves a succession of phylogenetic clades. In the Baltic Sea, the community is dominated by clades A/B for most of the year, but shifts to the S5.2 clade during summer when low NO₃, high PO₄, and warm temperatures create favorable conditions [14].

Beyond seasonal cycles, picocyanobacteria respond to short-term extreme events. Sampling during the 2023 marine heatwave in the Northern California Current revealed a clear shift in the picophytoplankton community towards smaller cell sizes [15]. This indicates that episodic warming events can rapidly alter community structure, potentially impacting carbon export efficiency due to the relationship between cell size and sinking rate.

Long-term studies in nutrient-limited systems, such as the Qingcaosha Reservoir, demonstrate that cyanobacterial blooms can persist even after nutrient loads are reduced to mesotrophic or oligotrophic conditions [17]. This suggests that once established, picocyanobacterial populations can sustain themselves through complex feedback mechanisms, including interactions with heterotrophic bacteria that facilitate nutrient cycling, thus decoupling their abundance from initial high nutrient concentrations [17].

Physiological and Molecular Basis of Distribution Patterns

The observed spatial and temporal patterns are underpinned by specific physiological adaptations and molecular mechanisms that allow picocyanobacteria to thrive in diverse and dynamic estuaries.

Temperature Adaptation and Photophysiology

Temperature is a primary factor driving the diversification of picocyanobacteria into distinct thermal ecotypes. Tropical strains (e.g., Clade II) exhibit high optimal growth temperatures (>25°C) and induce very high growth rates at elevated temperatures by synthesizing large amounts of photosynthetic machinery, thereby increasing photosystem cross-sections and electron flux [10]. In contrast, subpolar strains (e.g., Clade I) grow more slowly but survive at temperatures below 10°C. A key adaptation in cold-adapted ecotypes is the robust photoprotective capacity mediated by the Orange Carotenoid Protein (OCP) [10]. Metagenomic analyses confirm that OCP genes have the highest prevalence in low-temperature niches, whereas many tropical clade II Synechococcus have lost this gene [10]. This represents a clear evolutionary trade-off between high-growth and stress-tolerance strategies.

Carbon Concentration Mechanisms (CCMs) and Response to pCOâ‚‚

A critical physiological trait for carbon fixation is the operation of Carbon Concentration Mechanisms (CCMs). Laboratory studies exposing multiple Synechococcus strains to future climate conditions (22–26°C and 400–800 ppm CO₂) found that temperature was a stronger driver of changes in growth and photophysiology than CO₂ [12]. The minimal response to varying CO₂ levels is attributed to the CCMs operational in these strains, which shield the photosynthetic machinery from directly sensing ambient CO₂ changes [12]. This suggests that the direct effect of ocean acidification on picocyanobacterial growth may be limited, though interactive effects with temperature and light are possible.

Silicon Accumulation and Carbon Export

A novel physiological trait with implications for carbon dynamics is the accumulation of silicon (Si). While diatoms are the classic silicifiers in the ocean, certain Synechococcus strains can accumulate significant amounts of Si internally [16]. The chemical form of this Si differs from diatom opal-A and is potentially associated with organic matter [16]. This Si accumulation can increase cell density, enhancing sinking rates and potentially promoting the export of organic carbon to the deep ocean [16]. This pathway may represent a non-negligible contribution to the biological carbon pump, especially in oligotrophic waters where Synechococcus dominates.

Methodologies for Studying Picocyanobacterial Dynamics

Field Sampling and Hydrological Measurements

Standardized field protocols are essential for comparative studies. Integrated cruises collect surface water samples (e.g., from the top 25 m) using CTD rosettes equipped with Niskin bottles [15]. The CTD sensor package typically includes a SBE 3 temperature sensor, SBE 4 conductivity sensor, SBE 42/43 dissolved oxygen sensor, a pressure sensor, and an ECO-AFL fluorescence sensor for chlorophyll-a [15]. Parallel water samples are taken for subsequent biological (flow cytometry, DNA) and chemical (inorganic nutrient analysis) processing. Corresponding hydrological data (salinity, temperature, nutrient concentrations) are often provided through long-term monitoring programs [13].

Flow Cytometry for Enumeration and Sizing

Flow cytometry (FCM) is the cornerstone technique for quantifying picocyanobacterial abundance and estimating cell size. Cells are identified and enumerated based on their unique autofluorescence signatures from blue and red laser excitation [13] [15]. For example, the Guava EasyCyte HT flow cytometer is used for this purpose [13]. FCM allows for the discrimination of different functional groups, such as phycoerythrin-rich (PE-SYN) and phycocyanin-rich (PC-SYN) picocyanobacteria, as well as photosynthetic picoeukaryotes (PPE) [15] [14]. Cell size can be estimated from light-scattering properties, which was instrumental in detecting the shift to smaller cells during the 2023 marine heatwave [15].

Molecular Analysis of Community Composition

To resolve the vast diversity within picocyanobacteria, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing is widely employed. The standard protocol involves:

- DNA Extraction: From planktonic biomass collected on 0.22-μm filters using commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen PowerWater Kit), often with freeze-thaw cycles to increase yield [13].

- PCR Amplification: Using cyanobacterial-specific primers (e.g., CYB359-F and CYB781-R) targeting the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene, with added linker sequences for library preparation [13].

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Processing: Illumina MiSeq sequencing is common. Subsequent processing involves primer removal with tools like cutadapt, denoising, and chimera removal with DADA2 to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment is performed using classifiers like the RDP classifier against the SILVA database [13]. This high-resolution approach can reveal thousands of unique ASVs, highlighting an unprecedented diversity [14].

Biomass and Photosynthetic Efficiency Measurements

- Chlorophyll-a Measurements: Total and size-fractionated chlorophyll-a (a proxy for biomass) is determined fluorometrically. Biomass on GF/F filters is extracted with acetone (100%) using sonication, followed by fluorometric analysis [13].

- Pulse Amplitude Modulation (PAM) Fluorometry: This technique is used to assess the photophysiological status of cells. Parameters such as the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fᵥ/Fₘ) and the effective absorption cross-section of PSII (σPSII) can be measured. Electron transport rates (ETRII) versus irradiance curves can also be generated to understand light utilization under different temperatures [10] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the integration of these core methodologies into a standard workflow for a comprehensive analysis of picocyanobacterial dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Picocyanobacterial Ecology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Protocol & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacterial-Specific PCR Primers (e.g., CYB359-F, CYB781-R) [13] | Amplification of the 16S rRNA V3-V4 region for community diversity studies. | Used with CS1/CS2 linker sequences for Illumina library prep; triplicate PCR reactions are pooled [13]. |

| PowerWater DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) [13] | DNA extraction from environmental biomass collected on filters. | Protocol modified with three freeze-thaw cycles pre-extraction to increase DNA yield [13]. |

| SILVA v138 Database [13] | Reference database for taxonomic assignment of 16S rRNA amplicon sequences. | Used with RDP classifier within DADA2 pipeline; minimum bootstrap confidence of 80% [13]. |

| Modified SN Medium [12] | Defined culture medium for laboratory studies of Synechococcus strains. | Contains NaNO₃, Kâ‚‚HPOâ‚„, EDTA, Naâ‚‚CO₃, vitamins (Bâ‚â‚‚), trace metals; used for multistressor experiments [12]. |

| Guava EasyCyte HT Flow Cytometer (Millipore) [13] | Enumeration and characterization of picocyanobacteria based on autofluorescence. | Identifies populations via blue and red laser excitation; limit of quantification ~16 cells mLâ»Â¹ [13]. |

| Euphorbia factor L8 | Euphorbia factor L8, MF:C30H37NO7, MW:523.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yadanzioside K | Yadanzioside K, MF:C36H48O18, MW:768.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Carbon Fixation and Future Research

The spatial and temporal dynamics of picocyanobacteria have direct consequences for carbon fixation in estuaries. Their ability to form a resilient core community across salinity gradients [13] and dominate phytoplankton biomass in summer [14] positions them as a stable, continuous source of primary production. Furthermore, emerging mechanisms like silicon accumulation [16] and virus-mediated reprogramming of carbon metabolism [11] reveal pathways that significantly influence the fate of fixed carbon—whether it is channeled into the microbial loop or exported to depth.

Future research must prioritize integrated, multi-stressor experiments to unravel the synergistic effects of warming, acidification, and nutrient changes on different picocyanobacterial ecotypes [12]. Furthermore, long-term temporal studies, leveraging both flow cytometry and high-resolution molecular tools, are essential to track community shifts in response to climate events like marine heatwaves [15] [14]. Finally, a greater focus on the symbiotic interactions between picocyanobacteria and heterotrophic bacteria is needed to fully understand the mechanisms that sustain blooms and facilitate carbon cycling in nutrient-limited estuarine waters [17].

Salinity and Temperature as Master Regulators of Community Composition and Succession

In estuarine ecosystems, picocyanobacteria stand as fundamental agents of carbon fixation, serving as the linchpin between environmental physical-chemical gradients and biogeochemical cycling. This in-depth technical guide examines the governing principles of how salinity and temperature orchestrate the composition, succession, and ecological function of picocyanobacterial communities. These two master variables act not in isolation, but in concert, filtering species by their physiological tolerance and genomic capacity for adaptation [18] [19]. The dynamic interplay between these abiotic regulators and picocyanobacterial life strategies dictates primary productivity, community turnover, and ultimately, the carbon flux in these critical transition zones [18] [20]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for accurately modeling ecosystem responses to ongoing climatic change and for predicting shifts in foundational microbial processes.

Genomic and Physiological Adaptations to Salinity

The salinity gradient presents one of the most formidable barriers to microbial life in estuaries. Picocyanobacteria inhabiting these systems exhibit a suite of genomic and physiological adaptations that define their niche and govern their distribution across the freshwater-marine continuum.

Genomic Footprints of Salinity Niche Partitioning

Comparative ecogenomics reveals distinct genetic demarcations between freshwater, brackish, and marine picocyanobacteria, elucidating the molecular basis of the "salinity divide." Analysis of cluster 5 picocyanobacteria shows a clear trend in core genomic features correlated with habitat salinity [19].

Table 1: Core Genomic Characteristics of Picocyanobacteria Across the Salinity Divide

| Habitat | Average Genome Size (Mb) | Average %GC Content | Key Salinity Adaptation Genes/Pathways | Proteome Charge Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater | ~2.9 Mb | ~64% | Specific ion/potassium channels; aquaporin Z; fatty acid desaturases [19] | More neutral/basic [19] |

| Brackish | ~2.69 Mb | ~64% | Mixed marine & freshwater features; salt adaptation pathways (e.g., ggp/gpg clusters) [19] | Transitional [19] |

| Marine | ~2.5 Mb | ~58.5% | Osmolyte/compatible solute synthesis (glycine betaine; ggp/gpg/gmg clusters); glycerolipid metabolism (glpK/glpA) [19] | Acidic [19] |

The larger, GC-rich genomes of freshwater strains suggest a capacity for greater genetic flexibility and adaptation to a wider array of ecological niches compared to the more homogeneous marine environment [19]. The acidic proteomes of marine isolates are thought to enhance protein function and folding stability under high ionic strength [19].

Ecophysiological Consequences and Community Composition

These genomic adaptations translate directly into ecophysiological performance and distribution. Estuaries like the Chesapeake Bay host a diverse picocyanobacterial assemblage precisely because different genotypes possess the traits to exploit specific salinity regimes. The Bay contains freshwater Synechococcus and Cyanobium near river inflows, marine Synechococcus influenced by tidal exchange, and unique estuarine subcluster 5.2 Synechococcus adapted to the variable conditions in between [18] [2]. These estuarine specialists often show broader tolerance to salinity fluctuation and heavy metals than their open-ocean or freshwater counterparts [18]. Furthermore, the presence of abundant toxin-antitoxin (TA) genes in many Chesapeake Bay isolates suggests a genetic strategy for coping with the sharp physicochemical shifts characteristic of an estuary [18] [2].

Temperature-Driven Dynamics and Seasonal Succession

Temperature acts as a primary regulator of metabolic activity and triggers distinct seasonal successional patterns in picocyanobacterial communities. Its effects are pervasive, influencing growth rates, photosynthetic efficiency, and the timing of community turnover.

Seasonal Community Shifts

Long-term and high-resolution studies unequivocally demonstrate temperature-linked succession. In the Chesapeake Bay, distinct winter and summer picocyanobacterial communities are observed, indicating a dynamic seasonal shift that is likely tied to optimal growth temperatures of different genotypes [18]. A year-long, high-resolution dataset from the Warnow River estuary further confirms that microbial community composition, including picocyanobacteria, follows clear seasonal patterns, with temperature being a major driving factor alongside salinity [21].

Physiological Response to Temperature Stress

The effect of temperature on physiology is complex and often interacts with other stressors. Research on a marine Synechococcus strain in co-culture with a diatom and a cryptophyte revealed that its growth response to temperature (20–26°C) was highly dependent on the concomitant salinity level [22]. While the diatom and cryptophyte saw reduced growth at high temperature and salinity, Synechococcus sp. exhibited enhanced growth with increased temperature at a salinity of 36, demonstrating a taxon-specific, synergistic interaction between these two variables [22]. This suggests that in a warming climate with altered salinity patterns, competitive outcomes between phytoplankton groups may be reshuffled.

Photosynthetic performance, a key indicator of cellular health, is also temperature-sensitive. Studies of Prochlorococcus-dominated communities in the South China Sea show characteristic diel patterns in the maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), with midday declines indicative of nutrient stress and photo-inhibition [20]. Temperature influences the severity of this photoinactivation, as Prochlorococcus invests less energy in repairing damaged photosystems under high-light stress compared to Synechococcus [20].

Figure 1: Conceptual model of temperature-driven seasonal succession in estuarine picocyanobacteria. Seasonal temperature shifts select for distinct communities, which manifest in different physiological states and ultimately dictate ecological function, particularly carbon fixation.

Interactive Effects on Community Structure and Carbon Fixation

In natural ecosystems, salinity and temperature do not act independently. Their synergistic interaction creates a complex template upon which biological interactions and processes, particularly carbon fixation, are imprinted.

Microbial Interactions and Nutrient Cycling in a Changing Environment

The stability and function of picocyanobacterial communities, especially in nutrient-limited oligotrophic waters, are increasingly understood to rely on intricate relationships with heterotrophic bacteria. These picocyanobacterial-bacterial interactions form a reciprocal system: cyanobacteria release dissolved organic matter (DOM) through photosynthesis, and heterotrophic bacteria remineralize nutrients, making them bioavailable again for the cyanobacteria [17]. This close coupling suggests that the overall response of the carbon fixation engine of an estuary to shifts in salinity and temperature will depend not just on the picocyanobacteria themselves, but on the resilience of this entire interactive network [17]. Climate change-induced salinization, even in soil environments, has been shown to alter microbial metabolic activity and carbon use efficiency, highlighting the potential for unforeseen consequences for matter and energy turnover in vulnerable ecosystems [23].

Methodologies for Investigating Salinity and Temperature Effects

A suite of advanced techniques is required to dissect the complex effects of salinity and temperature on picocyanobacterial communities, from in situ observations to controlled laboratory manipulations.

High-Resolution Field Monitoring and Metabarcoding

Tracking community dynamics at ecologically relevant scales requires intensive sampling campaigns. The protocol employed in the Warnow River estuary study exemplifies this approach [21]:

- Spatio-Temporal Design: Surface water samples are taken from multiple sites along the salinity gradient (e.g., 15 sites over ~30 km) up to twice weekly for an entire year.

- Environmental Parameters: In-situ measurements and water samples are analyzed for temperature, salinity, chlorophyll a, and nutrient concentrations (nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, phosphate).

- Biotic Community Analysis: Flow cytometry provides absolute cell counts and picoplankton group abundance. High-throughput 16S and 18S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (metabarcoding) resolves prokaryotic and eukaryotic community composition, respectively.

- Data Integration: Powerful statistical tools are then used to correlate temporal shifts in community structure with the measured environmental drivers, revealing the influence of salinity, temperature, and season.

Laboratory Cultivation and Ecophysiological Profiling

Controlled experiments are essential for isolating the effects of and interactions between specific variables.

- Strain Isolation and Culture: Picocyanobacteria are isolated from various salinity habitats using appropriate media (e.g., BG-11 for freshwater, artificial seawater for marine) [19] [22].

- Experimental Microcosms: Isolates or natural communities are exposed to a matrix of salinity and temperature conditions in a laboratory setting [24] [22]. For example, testing growth across temperatures (e.g., 20, 23, 26°C) combined with salinities (e.g., 33, 36, 39) [22].

- Growth and Physiological Metrics: Growth rates are monitored via flow cytometry or chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynthetic performance is assessed using Fast Repetition Rate Fluorometry (FRRF) or PAM fluorometry to derive parameters like Fv/Fm [20] [25]. Additional assays can measure intracellular ROS, pigment composition, and nutrient uptake rates [22].

Optimized Fluorometry for Picocyanobacteria

Accurately measuring the photosynthetic competency of picocyanobacteria, particularly in mixed communities, requires careful configuration of fluorometric systems due to their unique pigment architecture [25].

- Excitation Wavelength: Blue light (450-470 nm) effectively excites algae but poorly represents cyanobacteria with phycoerythrin. Orange-red excitation (590-650 nm) provides the best correlation with cyanobacterial variable fluorescence [25].

- Emission Detection: A narrow emission slit (up to 10 nm) centered at ~683 nm (PSII Chl a emission) is critical to avoid signal dampening from weakly variable phycobilisome fluorescence and non-variable PSI fluorescence [25].

- Instrument Calibration: With these optimizations, healthy cyanobacteria in nutrient-replete conditions can exhibit Fv/Fm values of 0.65–0.7, comparable to algae, correcting the previous underestimation [25].

Figure 2: Integrated methodological workflow for studying salinity and temperature effects. A combination of field monitoring, laboratory experiments, and genomic analysis produces complementary data streams that, when synthesized, yield a mechanistic understanding of how these factors regulate picocyanobacterial ecology.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods for Picocyanobacterial Research

| Item/Method | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BG-11 & Artificial Seawater Media | Culture and maintenance of freshwater and marine picocyanobacterial isolates, respectively. | Formulations can be modified to create specific salinity gradients for ecophysiological experiments [19] [22]. |

| Fast Repetition Rate Fluorometry (FRRF) | Measures photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) and electron transport in vivo. | Must be configured with appropriate excitation wavelength (blue for algae; orange-red for PE-rich cyanobacteria) to avoid taxonomic bias [20] [25]. |

| Flow Cytometry | High-throughput quantification of picocyanobacterial abundance and cell characteristics. | Enables rapid monitoring of population growth in experiments and field surveys; can distinguish picocyanobacteria by pigment signatures [21] [22]. |

| 16S/18S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing (Metabarcoding) | Profiling prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial community composition from environmental DNA. | Reveals taxonomic structure and relative abundance; requires primers that adequately cover picocyanobacterial diversity [21]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., MagMAX) | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from filters for subsequent sequencing. | Optimized protocols for environmental water samples with low biomass are critical for success [21]. |

Salinity and temperature function as master ecological filters, governing the community composition and succession of picocyanobacteria in estuarine systems through direct physiological pressure and indirect biotic interactions. The genomic divide between freshwater and marine lineages, the predictable seasonal succession of genotypes, and the synergistic physiological responses to combined stressors all underscore their paramount regulatory role. The carbon fixation capacity of estuaries, driven significantly by picocyanobacteria, is therefore intrinsically linked to the dynamics of these two physical factors. Future research, integrating high-resolution 'omics with refined ecophysiological assessments across realistic environmental gradients, will be crucial for forecasting the stability of these ecosystems under the evolving pressures of climate change, including warming and altered precipitation patterns that directly impact salinity regimes. A comprehensive understanding of these master regulators is not merely an academic pursuit but a prerequisite for effective ecosystem management and conservation.

The Impact of Riverine Discharge and Nutrient Gradients on Population Structure

The dynamic interface where freshwater meets the ocean creates a complex and biologically critical environment. In estuaries, riverine discharge establishes pronounced physical and chemical gradients, with salinity and nutrient availability as primary determinants of microbial community structure [26]. Picocyanobacteria, particularly those within the Synechococcus and Cyanobium genera, emerge as keystone organisms in these transitional waters, serving as significant contributors to primary production and carbon fixation [13] [27]. Understanding how population structures of these microorganisms shift along estuarine gradients is fundamental to predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change. This technical guide synthesizes current research on the mechanisms through which riverine discharge and associated nutrient gradients shape picocyanobacterial populations, with direct implications for their role in estuarine carbon cycling.

Estuarine Gradients and the Picocyanobacterial Niche

The Salinity-Nutrient Nexus

Riverine discharge delivers distinct chemical signatures to estuarine systems, creating a gradient that ranges from nutrient-rich, turbid freshwater to nutrient-poor, clear saline waters. The resulting salinity gradient is often paralleled by shifts in nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and dissolved organic matter (DOM) concentrations [26]. In the Yangtze River Estuary, for example, spatial variation in bacterial community diversity clearly delineates riverine, transitional, and coastal regions, with salinity identified as the primary driver [26]. This physical-chemical framework establishes distinct niches for picocyanobacterial ecotypes with varying physiological tolerances.

Picocyanobacteria as Model Organisms

Picocyanobacteria (<2 µm in diameter) are ideal model organisms for studying population responses to environmental gradients. Their small size confers a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, enhancing nutrient uptake in oligotrophic conditions [28]. In the Northern California Current (NCC) system, picocyanobacteria demonstrate remarkable spatial and temporal plasticity, with abundances increasing with distance from shore and showing strong seasonal signals [15]. The estuarine environment hosts a genetic diversity of picocyanobacteria, including subcluster 5.2 Synechococcus, which contains strains adapted to the fluctuating conditions of brackish waters [2] [14]. The core picocyanobacterial community in the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound System (APES), consisting of Synechococcus, Cyanobium, and Synechocystis, exhibits resilience across significant salinity fluctuations, highlighting their adaptive capacity [13].

Quantitative Population Dynamics Along Gradients

Abundance and Distribution Patterns

Systematic studies across diverse estuarine systems reveal consistent patterns in picocyanobacterial abundance and composition relative to freshwater influence.

Table 1: Picocyanobacterial Abundance and Composition Across Estuarine Systems

| Estuarine System | Freshwater / Low-Salinity Zone | Transitional Zone | High-Salinity / Marine Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuse River Estuary (USA) [27] | PC-rich Synechococcus dominates (~10ⶠcells mLâ»Â¹) | Community shift | PE-rich Synechococcus dominates |

| Chesapeake Bay (USA) [2] | Freshwater Synechococcus & Cyanobium | Genetic mixing | Marine Synechococcus (5.1, 5.2) |

| Baltic Sea [14] | PC-SYN linked to stratification/shallow waters | - | PE-SYN correlates with Nâ‚‚-fixers |

| Kuroshio Current [28] | - | - | Synechococcus: 10â´-10âµ cells mLâ»Â¹Prochlorococcus: >10âµ cells mLâ»Â¹ |

Carbon Fixation Contributions

The population shifts detailed in Table 1 have direct consequences for the carbon cycle. Picocyanobacteria are significant contributors to estuarine primary production, with their carbon fixation potential varying along the gradient:

- In the Neuse River Estuary, picophytoplankton (dominated by Synechococcus-like cells) contribute approximately 40% of total phytoplankton biomass on average, rising to >70% during summer periods [13] [27].

- In the oligotrophic Kuroshio Current, picocyanobacteria (Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus) contribute more than 50% of the total chlorophyll a [28], underscoring their role as key primary producers in nutrient-poor waters.

- In the Northern California Current, the relationship between picocyanobacteria and photosynthetic picoeukaryotes (PPE) varies across on-to-offshore transects, indicating complex interactions that influence overall carbon fixation capacity [15].

Table 2: Environmental Drivers of Picocyanobacterial Population Structure

| Environmental Factor | Impact on Population Structure | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Salinity [13] [26] | Determines phylotype distribution & diversity | Strong driver of community assembly; selects for specific ecotypes (e.g., PC-rich vs. PE-rich) |

| Temperature [15] [27] | Influences seasonal abundance & growth rates | Explains 24.5% of variation in PicoP abundance in NRE; promotes summer peaks |

| Nitrogen (N) [15] [14] | Limits growth & selects for adapted lineages | Cell abundances correlate negatively with NO₃; PE-SYN abundance correlates with N₂-fixers |

| River Flow/Discharge [27] | Physically displaces populations, alters nutrients | 15.9% of PicoP variation in NRE; extreme events cause ~100-fold biomass reduction |

Research Methodologies for Population Analysis

Field Sampling and Hydrological Measurement

Standardized sampling protocols are essential for comparative studies of estuarine gradients. Research cruises typically employ a transect approach from riverine to marine stations [15]. At each station, surface water samples are collected using Niskin bottles mounted on a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth) rosette system [15] [28]. The CTD provides high-resolution vertical profiles of salinity, temperature, fluorescence (as a proxy for chlorophyll a), and dissolved oxygen [15]. Additional water samples are collected for nutrient analysis (nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, phosphate, silicate), typically filtered and frozen until analysis using standard colorimetric methods [14] [28].

Picoplankton Enumeration and Characterization

Flow Cytometry (FCM) is the primary method for quantifying picocyanobacterial abundances and distinguishing functional groups based on pigment signatures [15] [27]. The standard protocol involves:

- Sample Fixation: Preserving water samples with glutaraldehyde (final concentration 0.25-1%) [13] [27].

- Analysis: Analyzing samples using flow cytometers equipped with blue (488 nm) and red (600 nm) lasers [27].

- Identification: Distinguishing PC-rich Synechococcus (PC-SYN), PE-rich Synechococcus (PE-SYN), and picoeukaryotes (PEUK) based on their distinct pigment fluorescence and light scatter signatures [14] [27].

- Cell Sizing: Using spherical reference beads of known diameter to convert forward scatter measurements into cell size estimates [27].

- Biomass Calculation: Converting biovolume to carbon biomass using established factors (e.g., 237 fg C μmâ»Â³) [13].

Molecular Analysis of Community Composition

Genetic methods provide high-resolution insights into population diversity and structure:

- DNA Extraction: Biomass is collected via vacuum filtration onto 0.22 μm filters, with DNA extracted using commercial kits like the PowerWater Kit (Qiagen) [13].

- Amplicon Sequencing: Targeting the 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 or V4-V5 hypervariable regions with cyanobacteria-specific primers (e.g., CYB359F/CYB781R) or universal primers (e.g., 515F/926R) [13] [26].

- Sequence Analysis: Processing reads through pipelines like DADA2 to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) followed by taxonomic classification against reference databases (e.g., SILVA) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Estuarine Picocyanobacteria Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| CTD-Rosette System | High-resolution hydrographic data collection | Sea-Bird SBE 9/11 plus with Niskin bottles [15] [28] |

| Flow Cytometer | Picophytoplankton enumeration & differentiation | Guava EasyCyte HT; triggering on red fluorescence [13] [27] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Microbial community DNA extraction from filters | PowerWater DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) [13] |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of target genes for diversity studies | KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix with cyanobacteria-specific primers [13] |

| Filter Membranes | Biomass collection for DNA & pigment analysis | 0.22 μm Supor filters (DNA); GF/F filters (Chl a) [13] |

| Fixatives | Sample preservation for FCM & microscopy | Glutaraldehyde (0.25-1% final concentration) [13] [27] |

| Nutrient Analysis Kits | Quantification of dissolved inorganic nutrients | Standard colorimetric assays for NO₃, NO₂, NH₄, PO₄ [14] |

| Reference Beads | Cell size calibration in flow cytometry | Spherotech beads (0.5-5.11 μm diameter) [27] |

| Potentillanoside A | Potentillanoside A, MF:C36H56O10, MW:648.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,6,16-Kauranetriol | 2,6,16-Kauranetriol, MF:C20H34O3, MW:322.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Carbon Fixation and Future Research

The population structure of picocyanobacteria has direct consequences for carbon fixation in estuarine ecosystems. Shifts toward smaller cells, as observed during marine heatwaves in the Northern California Current [15], can alter trophic transfer efficiency and carbon export pathways. The resilience of core picocyanobacterial communities across salinity gradients [13] suggests a potential buffering capacity for maintaining primary production under fluctuating conditions. However, extreme discharge events can disrupt this stability, causing dramatic reductions in picocyanobacterial biomass [27].

Future research should prioritize:

- High-Resolution Temporal Studies: Tracking population dynamics before, during, and after extreme discharge events.

- Metatranscriptomic Approaches: Linking population shifts to functional gene expression related to carbon and nutrient metabolism.

- Integration of Environmental Data: Combining molecular data with advanced hydrographic modeling to predict population responses to climate change.

- Expanded Geographic Coverage: Systematic comparisons across diverse estuarine systems to identify universal principles.

Understanding the intricate relationship between riverine discharge, nutrient gradients, and picocyanobacterial population structure is paramount for forecasting the carbon cycle dynamics of estuarine systems in a changing global climate.

Within the microbial tapestry of estuarine ecosystems, picophytoplankton (cells ≤ 3 µm in diameter) serve as foundational primary producers, fueling food webs and governing biogeochemical cycles. This group is primarily composed of two key players: picocyanobacteria (e.g., Synechococcus, Cyanobium) and picoeukaryotes (e.g., Ostreococcus, Micromonas). The dynamic competition and coexistence between these groups are largely dictated by the process of niche partitioning, where each group exploits distinct environmental niches based on their unique physiological adaptations. Understanding this partitioning is critical, especially within the context of estuarine carbon fixation, where picocyanobacteria contribute significantly to primary production and carbon sequestration. This review synthesizes current research to elucidate the mechanisms driving this niche separation and its implications for the structure and function of estuarine food webs.

Ecological Significance and Quantitative Contribution

Picophytoplankton are now recognized as major contributors to estuarine phytoplankton biomass and primary production, challenging the historical focus on larger phytoplankton.

Table 1: Quantitative Contributions of Picophytoplankton in Various Estuarine Systems

| Estuarine System | Picocyanobacteria Contribution | Picoeukaryote Contribution | Combined Picophytoplankton Contribution | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albemarle-Pamlico Sound System (APES), USA | ~72% of cyanobacterial sequences; ~47% of Chlorophyll a (with picoeukaryotes) | Part of ~47% of Chlorophyll a (with picocyanobacteria) | ~47% of total phytoplankton Chlorophyll a | [13] |

| Kandla Port, India | Dominant during warm periods (Oct-Nov) | Dominant during cool periods (Feb) | Major contributor to total phytoplankton abundance | [29] |

| Neuse River Estuary (NRE), USA | >70% of picophytoplankton during summer | Variable seasonal contribution | Averaged ~40% of total Chlorophyll a | [13] |

The data in Table 1 underscores the pervasive importance of picophytoplankton. In the APES, picocyanobacteria belonging to Synechococcus, Cyanobium, and Synechocystis formed a core community spanning freshwater to polyhaline regions, demonstrating remarkable resilience to salinity fluctuations [13]. This resilience is a key trait enabling their persistence and success in dynamic estuaries.

Methodologies for Studying Picophytoplankton Dynamics

A combination of advanced techniques is required to dissect the abundance, diversity, and functional roles of picophytoplankton.

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Picophytoplankton Research

| Methodology | Key Item/Reagent | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Guava EasyCyte HT (Millipore) | Identify, count, and sort picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes based on cell size and pigment autofluorescence. |

| Molecular Diversity Analysis (16S/18S rRNA) | CYB359-F/CYB781-R primers; PowerWater DNA Kit (Qiagen) | Amplify and sequence genetic markers to determine taxonomic composition and diversity of picocyanobacterial communities. |

| Chlorophyll a Biomass Estimation | Glass Fiber Filters (GF/F); acetone (100%) | Extract and measure Chlorophyll a via fluorometry to estimate total and size-fractionated phytoplankton biomass. |

| Biogenic Silica (bSi) Measurement | Alkaline digestion (e.g., 0.1M Na2CO3) | Quantify silica accumulation in picoplankton cells using a spectrophotometric assay, challenging the diatom-silica paradigm. |

| Culture-Based Experiments | L1 media (prepared with artificial seawater) | Isolate and maintain picophytoplankton strains to study physiological responses (e.g., Si uptake) under controlled conditions. |

Integrated Workflow for Community and Functional Analysis

The following workflow, derived from established protocols, outlines a pathway from sample collection to data integration [13] [30].

Mechanisms of Niche Partitioning

Niche partitioning between picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes is driven by differential responses to abiotic factors and distinct metabolic capabilities.

Temperature and Salinity Gradients

Temperature is a primary driver of seasonal succession. A study in Kandla Port, India, found a clear temporal niche segregation: picocyanobacteria (specifically Synechococcus phycoerythrin-rich types I and II) dominated during the warm (27.9-29.2°C), non-monsoon period, while picoeukaryotes, including cryptophytes, became dominant during the cooler (20.8°C) winter period [29]. This suggests that temperature optima are a key factor separating these groups.

Salinity also structures communities. In the Chesapeake Bay, distinct picocyanobacterial lineages, including freshwater (Cyanobium), estuarine (subcluster 5.2 Synechococcus), and marine types, are distributed along the salinity gradient from the northern to the southern Bay [18]. The presence of a "core community" of picocyanobacteria in the APES that persists across a wide salinity range further highlights their adaptability, a trait less pronounced in many picoeukaryotes [13].

Nutrient Utilization and Metabolic Adaptations

Genomic analyses reveal that picocyanobacteria possess specialized gene clusters (ecologically significant Gene Clusters, eCAGs) that allow them to thrive in nutrient-depleted conditions. These eCAGs are enriched for the uptake and assimilation of complex organic nutrients like guanidine, cyanate, cyanide, pyrimidines, and phosphonates [31]. This metabolic flexibility provides a competitive edge in oligotrophic estuaries.

Furthermore, picocyanobacteria engage in synergistic relationships with heterotrophic bacteria. In nutrient-limited waters, cyanobacterial-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) supports bacterial growth, which in turn remineralizes nutrients into bioavailable forms (e.g., ammonium, nitrate) that picocyanobacteria can readily uptake, creating a positive feedback loop that sustains cyanobacterial blooms even in oligotrophic conditions [17].

The Emerging Role of Silicon Accumulation

A paradigm-shifting discovery is the significant accumulation of biogenic silica (bSi) by both picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes, despite lacking siliceous frustules [16] [30]. Laboratory studies show strains of Synechococcus and picoeukaryotes like Ostreococcus tauri and Micromonas commoda can accumulate 30 to 92 attomoles of Si per cell when dissolved silica is available [30]. The function of this Si accumulation remains unclear, but it may:

- Increase cell density, enhancing sinking rates and facilitating carbon export to deeper waters [16].

- Provide structural strength or defense against grazing. This finding positions both groups as novel, potentially important players in the estuarine and oceanic silica cycle, a role previously ascribed almost exclusively to diatoms.

Implications for Carbon Fixation and Food Webs

The partitioning between picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes has direct consequences for carbon flow in estuarine ecosystems.

Carbon Pathway: Picoeukaryotes, due to their larger size, are generally considered a more direct and efficient link to higher trophic levels like mesozooplankton. In contrast, picocyanobacteria primarily enter the food web through microbial loops, involving nanoflagellate grazers and heterotrophic bacteria, leading to longer carbon pathways with greater respiratory losses [29].

Carbon Export: The discovery of Si accumulation adds a new dimension to the role of picocyanobacteria in carbon sequestration. Si-ballasted Synechococcus cells have higher sinking rates, potentially enhancing the export of organic carbon from the surface to the deep ocean (the biological carbon pump) [16]. This mechanism suggests that picocyanobacteria may contribute more significantly to long-term carbon burial than previously thought.

Table 3: Comparative Summary of Picocyanobacteria and Picoeukaryotes in Estuaries

| Trait | Picocyanobacteria | Picoeukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Genera | Synechococcus, Cyanobium, Prochlorococcus | Ostreococcus, Micromonas, Bathycoccus |

| Optimal Temperature | Warm periods (e.g., >27°C) [29] | Cooler periods (e.g., ~20°C) [29] |

| Salinity Tolerance | Broad; form core communities across gradients [13] | Often more restricted to specific salinity regimes |

| Key Metabolic Adaptations | eCAGs for complex organic nutrient use [31]; symbiosis with bacteria [17] | -- |

| Silicon Accumulation | Yes (30-92 amol Si cellâ»Â¹ in some strains) [30] | Yes (30-92 amol Si cellâ»Â¹ in some strains) [30] |

| Role in Carbon Cycle | Major primary producer; carbon enters via microbial loop; potential Si-driven export [16] [17] | Major primary producer; more direct trophic transfer to zooplankton |

Conceptual Diagram of Niche Partitioning and Carbon Fate

The following diagram synthesizes how environmental drivers influence community structure and subsequent carbon pathways in an estuary.

The coexistence of picocyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes in estuarine ecosystems is a classic example of niche partitioning, driven by differential adaptations to temperature, salinity, nutrient availability, and unique metabolic strategies. Picocyanobacteria demonstrate a remarkable ability to thrive under warm, nutrient-limited conditions through genetic adaptations and symbiotic relationships, solidifying their role as a key contributor to estuarine carbon fixation. The emerging understanding of silicon accumulation in both groups further expands their perceived role in biogeochemical cycles, particularly in carbon export. Future research, leveraging the methodologies outlined herein, should focus on quantifying the carbon export potential of Si-ballasted picoplankton and forecasting how climate change-induced shifts in temperature and stratification might alter this delicate balance, thereby impacting the productivity and carbon sequestration capacity of estuarine systems globally.

Quantifying the Contribution: Advanced Techniques for Measuring Picocyanobacterial Biomass and Carbon Fixation

Flow cytometry has established itself as an indispensable tool in aquatic microbiology, particularly for the study of picocyanobacteria in estuarine ecosystems. This technical guide examines flow cytometry's capabilities in enumerating and differentiating picocyanobacterial morphotypes, with specific application to carbon fixation research. We detail standardized methodologies, data interpretation frameworks, and advanced applications that enable researchers to quantify picocyanobacterial abundance, assess physiological status, and evaluate their significant contribution to estuarine carbon cycling. The precision and statistical power offered by flow cytometry—processing thousands of cells per second with multi-parameter data collection—makes it superior to traditional microscopy for picocyanobacterial population dynamics studies in rapidly changing estuarine environments.

Picocyanobacteria, particularly the genus Synechococcus, play a critically understudied role in estuarine carbon fixation. These microscopic cyanobacteria (0.5–3 µm in size) contribute significantly to primary productivity in transitional waters where freshwater and marine ecosystems converge [32]. Recent research has revealed that estuarine picocyanobacteria exhibit enhanced tolerance to fluctuations in temperature, salinity, and heavy metals compared to their coastal and open-ocean counterparts, making them particularly important in the face of environmental change [32].

The foundational architecture of ecosystem health depends heavily on microbial communities, with biodiversity decline risking systemic destabilization of essential services [32]. Within this framework, picocyanobacteria constitute a vital component of the microbial food web, contributing substantially to carbon fixation through oxygenic photosynthesis. In temperate estuaries like Chesapeake Bay, dynamic seasonal shifts shape picocyanobacterial communities, with novel subcluster 5.2 Synechococcus lineages demonstrating remarkable adaptability to estuarine conditions [32]. Understanding the dynamics of these populations is essential for evaluating the broader carbon cycle in estuarine environments, which function as significant carbon processing zones between terrestrial and marine systems.

Flow Cytometry Fundamentals

Core Principles and Technical Advantages

Flow cytometry operates on the principle of hydrodynamic focusing, where cells in suspension pass single-file through a laser beam, scattering light and emitting fluorescence that is detected and converted into digital signals [33]. This technology provides several distinct advantages for picocyanobacteria research:

- High-throughput analysis: Capacity to process >10,000 events per second, enabling robust statistical analysis of population distributions [33]

- Multi-parameter data collection: Simultaneous measurement of forward scatter (FSC, indicative of cell size), side scatter (SSC, indicative of cell granularity/internal complexity), and multiple fluorescence channels [33]

- Non-destructive analysis: Cells remain viable for subsequent cultural experiments or sorting applications

- High sensitivity: Detection of faint autofluorescence from photosynthetic pigments in small picocyanobacteria

Comparative Methodological Advantages

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Picocyanobacteria Analysis

| Method | Enumeration Capability | Morphotype Differentiation | Throughput | Physiological Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | Excellent (statistically robust) | Good (based on scatter & fluorescence) | High (thousands per second) | Excellent (pigment content, viability) |

| Epifluorescence Microscopy | Good (visual confirmation) | Moderate (morphology visible) | Low (hours per sample) | Limited (basic morphology) |

| Metabarcoding | Indirect (relative abundance) | Excellent (genetic differentiation) | Moderate (post-processing) | None (community composition only) |

| FlowCAM | Good (image-based) | Excellent (visual morphotypes) | Moderate (hundreds per minute) | Moderate (size, shape metrics) |

Traditional methods like epifluorescence microscopy have provided valuable insights into picocyanobacteria abundance but yield inconsistent results when correlating with environmental drivers [34]. Flow cytometry overcomes these limitations by enabling rapid quantification while simultaneously collecting data on cell size and pigment composition, which are crucial parameters for differentiating picocyanobacterial populations and assessing their physiological status.

Experimental Protocols for Estuarine Picocyanobacteria

Sample Collection and Preservation

Materials Required:

- Niskin bottles or similar water sampling equipment

- Dark containers (amber glass or polycarbonate)

- Glutaraldehyde (electron microscopy grade, 25% solution)

- Liquid nitrogen or -80°C freezer for flash freezing

- Cryovials for sample storage

Protocol:

- Collect water samples from predetermined depths and locations within the estuary

- Pre-screen through 100-200µm mesh to exclude larger organisms

- Fix samples immediately with 0.1-1% glutaraldehyde (final concentration)

- Incubate in darkness for 10-15 minutes at room temperature

- Flash freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until analysis

- Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles to preserve cellular integrity and fluorescence signals

Instrument Calibration and Setup

Daily Quality Control Procedures:

- Run standardized fluorescent beads to calibrate scatter parameters and fluorescence detectors

- Adjust photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltages to optimize signal-to-noise ratio

- Establish triggering threshold on SSC or chlorophyll fluorescence to exclude debris and noise

- Verify detector performance using reference samples with known picocyanobacteria composition

Data Acquisition and Gating Strategy

The analytical workflow for picocyanobacteria analysis follows a sequential gating strategy to accurately identify and characterize target populations.

Diagram 1: Flow Cytometry Gating Strategy for Picocyanobacteria Analysis

Acquisition Parameters:

- Flow rate: Set to low or medium (≤60µL/min) to maximize resolution and minimize coincident events

- Events to acquire: Minimum of 10,000 events in the target gate or 1-2 minutes acquisition time

- Detectors:

- FSC: Logarithmic scale, threshold 5,000-10,000

- SSC: Logarithmic scale

- Fluorescence channels:

- Chlorophyll (red fluorescence): >670 nm (essential for all photosynthetic cells)

- Phycoerythrin (orange fluorescence): 570-580 nm (specific for certain Synechococcus strains)

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Graphical Data Representation

Flow cytometry data can be visualized in multiple formats, each providing different analytical insights:

Histograms present single-parameter data, typically displaying fluorescence intensity or forward scatter on the x-axis and cell count on the y-axis [33]. As the peak moves from left to right, signal intensity increases, indicating higher expression of the target detected by the fluorescent marker [33].

Scatter plots present multi-parameter data, mapping each event based on expression of two different parameters [33]. The FSC vs SSC plot is fundamental for initial cell population gating, while fluorescence parameter combinations enable differentiation of phytoplankton groups based on pigment signatures.

Table 2: Flow Cytometry Signatures of Common Estuarine Picocyanobacteria

| Population | FSC (Size) | SSC (Complexity) | Red Fluorescence (Chlorophyll) | Orange Fluorescence (Phycoerythrin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synechococcus (PE-rich) | Low | Low | Moderate | High |

| Synechococcus (PE-deficient) | Low | Low | Moderate | Low/Absent |

| Prochlorococcus | Very Low | Very Low | Low | Absent |

| Small Eukaryotes | Moderate-High | Variable | High | Variable |

| Detritus/Debris | Variable | Variable | Low/Absent | Low/Absent |

Quantitative Analysis of Carbon Fixation Potential

The contribution of picocyanobacteria to estuarine carbon fixation can be extrapolated from flow cytometry data using established conversion factors:

Calculation Method:

- Determine picocyanobacterial abundance (cells/mL) from flow cytometry counts

- Apply cell-specific carbon content conversion factors (5-30 fg C/cell, depending on cell size)

- Estimate carbon fixation rates using temperature- and light-adjusted productivity factors

- Relate population dynamics to seasonal environmental variables

Research in Chesapeake Bay has demonstrated that estuarine picocyanobacteria, particularly novel Synechococcus lineages in subcluster 5.2, play a disproportionately significant role in carbon fixation despite their small size, with their contribution varying seasonally in response to temperature, nutrient availability, and freshwater inflow [32].

Advanced Applications in Estuarine Research

Coupling with Molecular Techniques

While flow cytometry provides robust physiological and abundance data, its integration with molecular methods creates a powerful complementary approach. Metabarcoding of 16S rRNA genes reveals that diverse picocyanobacterial communities in estuaries respond to environmental variables in a strain-specific manner, explaining why studies treating picocyanobacteria as a single functional group produce inconsistent results [34].

Integrated Workflow:

- Analyze water samples by flow cytometry to determine abundance and population structure

- Sort specific subpopulations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

- Extract DNA/RNA from sorted populations for molecular analysis

- Correlate physiological properties with genetic identity and metabolic potential

Physiological Status Assessment

Advanced flow cytometric applications enable assessment of picocyanobacterial physiological status:

Viability Analysis:

- Use nucleic acid stains (e.g., SYTOX Green) to distinguish membrane-compromised cells

- Monitor esterase activity with fluorogenic substrates as an indicator of metabolic activity

Photosynthetic Efficiency:

- Analyze chlorophyll fluorescence quenching under different light conditions

- Correlate with FRRf (Fast Repetition Rate fluorometry) measurements of Fv/Fm (maximum quantum yield of PSII) [20]

Linking Population Dynamics to Carbon Cycling

The functional linkage between picocyanobacterial community composition and carbon cycling can be investigated by coupling flow cytometry with metabolic rate measurements:

Experimental Design:

- Monitor picocyanobacterial population dynamics over seasonal cycles

- Measure extracellular enzyme activities and organic matter processing rates

- Correlate specific population shifts with carbon processing metrics

- Identify keystone taxa driving carbon transformation processes

Metagenomic studies have revealed that Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Bacteroidota play critical roles in organic matter degradation in coastal waters, with distinct substrate processing and assimilation strategies among these taxa [32]. Understanding how picocyanobacterial productivity supports these heterotrophic communities is essential for modeling carbon flow in estuarine ecosystems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Picocyanobacteria Flow Cytometry

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Glutaraldehyde (25% solution) | Sample preservation | Optimal final concentration: 0.1-1%; incubate 10-15 min in dark |

| Fluorescent Standards | Fluorescent microspheres (1-3µm) | Instrument calibration | Use size-matched beads; verify stability over time |

| Viability Markers | SYTOX Green, Propidium Iodide | Membrane integrity assessment | Distinguish living vs. compromised cells |

| Metabolic Probes | CTC (5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride) | Respiratory activity | Indicates metabolically active cells |

| Sorting Matrix | UltraPure Agarose, Glycerol | Cell collection post-sorting | Maintains cell viability for downstream cultures |

| DNA Stains | DAPI, SYBR Green | Nucleic acid content | Cell cycle analysis, absolute counting |

| Culture Media | Modified low-nutrient media | Isolation of rare taxa | Essential for cultivating previously uncultured lineages [32] |

| Filtration Supplies | Sterile syringe filters (0.22µm) | Media sterilization | Maintain axenic conditions for cultures |

| Momordicoside P | Momordicoside P, MF:C36H58O9, MW:634.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sodium alginate | Sodium alginate, MF:C6H9NaO7, MW:216.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodological Workflow Integration