Public Health: The Invisible Shield Protecting Our World

How prevention, policy, and community effort create healthier populations

More Than Just Medicine: What Is Public Health?

When 19th century physician John Snow removed the handle from a London water pump to stop a deadly cholera outbreak, he wasn't treating individual patients—he was protecting an entire community. This groundbreaking action represents the very essence of public health: the science of protecting and improving the health of populations through prevention, policy, and organized community effort5 .

Clinical Medicine

Focuses on treating individuals after they become sick

Public Health

Aims to prevent disease and injury before they occur

Today, public health faces both unprecedented challenges and extraordinary opportunities. From emerging infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance to the mental health crisis and climate-related health threats, the field stands at the forefront of global wellbeing4 . Meanwhile, technological innovations and new research methodologies are revolutionizing how we approach these complex problems.

Public health creates "the invisible shield" that protects us all through science, policy, and prevention.

The Changing Face of Population Health: Today's Top Challenges

74%

of global deaths from non-communicable diseases4

1 in 5

people worldwide live with a mental health condition4

1.27M

annual deaths from antimicrobial resistance4

Key Concepts in Modern Public Health

Health Equity

The pursuit of eliminating health disparities across different populations7 .

Social Determinants

Conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age profoundly influence health1 .

One Health

Recognizes interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health4 .

Major Public Health Challenges

| Challenge | Key Statistics | Primary Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Communicable Diseases | 74% of all global deaths; 41 million annual deaths | Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic respiratory disease |

| Mental Health | 1 in 5 people affected globally; 4th leading cause of death in 15-29 year olds | Depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, suicide |

| Climate Change | 100 million at risk of poverty; 7 million annual air pollution deaths | Vector-borne disease expansion, heat-related illnesses, respiratory conditions |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | 1.27 million annual direct deaths; 10 million projected by 2050 | Untreatable infections, higher mortality, complicated medical procedures |

Global Impact of Key Health Challenges

Public Health Detective Work: The Natural Experiment

Learning from Unexpected Opportunities

While randomized controlled trials represent the gold standard in medical research, many public health questions can't be answered in laboratory settings. How do we study the health impact of policies, environmental changes, or social programs that affect entire communities?

Enter the natural experiment—a powerful methodological approach that observes populations before and after an event or intervention that researchers didn't control but can study systematically8 .

Natural experiment studies combine features of experiments and observational research. Unlike randomized controlled trials where researchers control exposure, in natural experiments, "allocation is not controlled by researchers"8 . What distinguishes them from other observational designs is that they "specifically evaluate the impact of a clearly defined event or process which result in differences in exposure between groups"8 .

Randomized Controlled Trials

Researchers control exposure allocation

Observational Studies

Researchers observe without intervention

Natural Experiments

Exposure allocation occurs naturally, not controlled by researchers

Case Study: John Snow and the Broad Street Pump

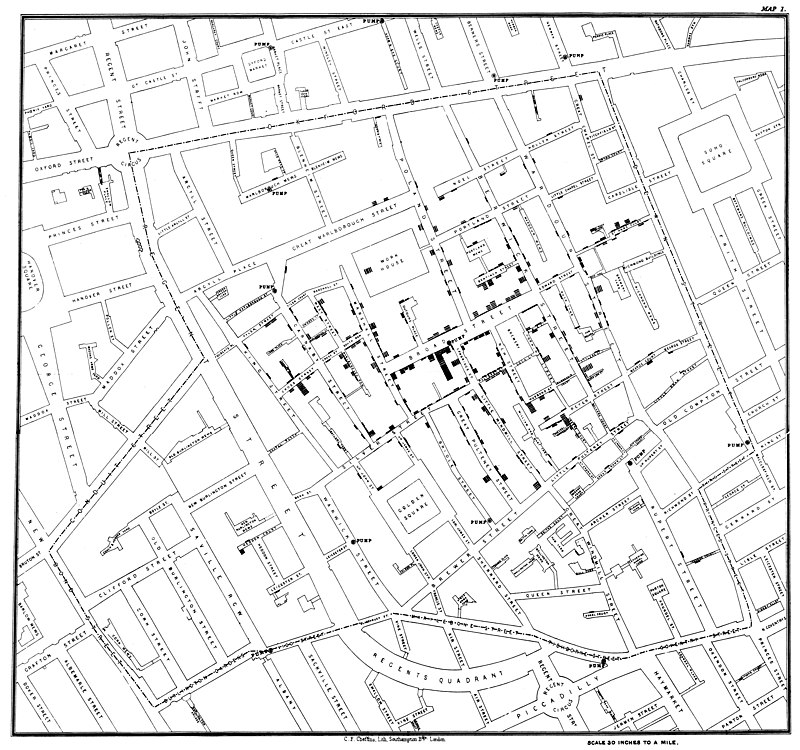

One of the most famous natural experiments in public health history occurred in 1854 London, when physician John Snow investigated a devastating cholera outbreak5 . At the time, the prevailing theory held that cholera spread through "bad air" or miasma. Snow hypothesized instead that contaminated water transmitted the disease.

His investigative methodology was groundbreaking:

- Case Mapping: Snow documented all cholera deaths in the Soho district, mapping each case to specific households

- Exposure Identification: He identified which households used which water sources, particularly the Broad Street pump

- Comparison Group: He found that workers at a nearby brewery who drank mainly beer (and little water) avoided infection

- Intervention: He persuaded authorities to remove the pump handle, effectively stopping the outbreak

- Further Verification: Later, he compared cholera death rates between areas served by two different water companies

John Snow's original cholera map showing clusters of cases around the Broad Street pump.

Landmark Natural Experiments in Public Health History

| Natural Experiment | Year | Health Focus | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Street Pump | 1854 | Cholera transmission | Contaminated water, not bad air, caused cholera outbreaks |

| Dutch Hunger Winter | 1944-1945 | Famine and health | Prenatal famine exposure increases risk of later-life metabolic disease |

| Canterbury Earthquakes | 2010-2011 | Disaster mental health | Natural disasters significantly impact long-term mental health outcomes |

| Smoking Bans | Various | Cardiovascular health | Smoke-free policies reduce cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality9 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Behind every public health breakthrough lies a sophisticated array of laboratory tools and materials. These reagents and instruments enable researchers to detect, understand, and combat health threats at molecular, cellular, and population levels.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA Kits | Detect antibodies or antigens | Measuring immune response to vaccines; detecting disease outbreaks |

| PCR Reagents | Amplify genetic material | Identifying pathogens; tracking disease variants |

| Cell Culture Media | Support growth of cells in laboratory | Studying host-pathogen interactions; testing therapeutics |

| Primary Antibodies | Bind specific target proteins | Disease mechanism research; diagnostic development |

| Viral Transport Media | Preserve virus integrity | Transporting patient samples for testing; pandemic surveillance |

| Statistical Software | Analyze population health data | Identifying risk factors; evaluating intervention effectiveness |

Laboratory Research

These tools enable everything from diagnostic test development to understanding disease mechanisms at the molecular level. For instance, in the NF-κB signaling research example from the Assay Guidance Manual, materials including formaldehyde, specific antibodies, and cell culture reagents were essential for understanding inflammatory responses at the cellular level3 .

Data Analysis

Statistical software and data analysis tools help identify patterns, risk factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of public health interventions across populations.

Innovations Shaping Tomorrow's Public Health Landscape

Technological Frontiers

AI and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence now powers diagnostic tools that analyze medical images, predict disease outbreaks, and identify patterns invisible to the human eye. Beyond diagnostics, AI is revolutionizing drug repurposing by identifying existing medications that could treat unrelated conditions2 .

CRISPR and Gene Editing

Cutting-edge gene editing technologies are revolutionizing therapeutic development. CRISPR-based therapies have shown promise for conditions from genetic disorders to viral infections and autoimmune diseases. The first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, Casgevy, marks just the beginning of this transformative approach2 .

Digital Health and Wearables

Advanced wearable devices now provide continuous health monitoring, tracking everything from heart rate to blood oxygen levels. These technologies enable early illness detection and remote management of chronic conditions, generating real-world data that informs both individual care and public health understanding.

Promising Public Health Innovations in 2025

| Innovation | Application | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Powered Diagnostics | Medical image analysis; outbreak prediction | Earlier detection; more accurate diagnoses; personalized treatment plans |

| Digital Therapeutics | Software-based interventions for chronic disease | Improved access; better adherence; reduced healthcare costs |

| CRISPR Therapeutics | Gene editing for genetic disorders; cancer; viral infections | Curative approaches for previously untreatable conditions |

| Wearable Health Monitors | Continuous tracking of vital signs; early anomaly detection | Preventive healthcare; real-time monitoring; reduced hospitalizations |

Molecular Editing

This emerging technique allows precise modification of a molecule's core structure by inserting, deleting, or exchanging atoms. Unlike traditional approaches that build molecules stepwise, molecular editing efficiently creates new compounds by modifying existing ones, potentially accelerating therapeutic development2 .

Precision Nutrition

Moving beyond one-size-fits-all dietary recommendations, this approach tailors advice to individual genetics, microbiome, and metabolic profiles. Though still emerging, it represents the future of personalized prevention strategies7 .

Our Collective Health: A Shared Responsibility

Public health has always been a collaborative endeavor, and in our interconnected world, this truth has never been more evident. The challenges are significant—from combating misinformation and addressing health inequities to building climate-resilient health systems and preparing for future pandemics4 . Yet the tools at our disposal are more powerful than ever before.

10 Million

Projected global shortage of healthcare workers by 20304

The future of public health will likely be shaped by our ability to integrate technological advances with equitable implementation, ensuring that innovations like AI diagnostics and wearable monitors benefit all populations, not just the privileged few. It will require sustained investment in public health infrastructure and workforce development.

Perhaps most importantly, public health reminds us that our wellbeing is interconnected. The choices we make as individuals and societies—from vaccination decisions to environmental policies—create ripple effects across communities and generations.

By supporting evidence-based policies, staying informed, and advocating for health equity, we all contribute to the invisible shield that protects our collective wellbeing. As John Snow demonstrated nearly two centuries ago, sometimes the most powerful health interventions don't treat individual illness but create conditions that allow entire communities to thrive.

The Invisible Shield

Protecting populations through science, policy, and prevention