Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding: A Spike-In DNA Framework for Robust Biomonitoring and Biomedical Application

Quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is revolutionizing biodiversity monitoring and ecological assessment by moving beyond simple presence-absence data to deliver quantitative species abundance estimates.

Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding: A Spike-In DNA Framework for Robust Biomonitoring and Biomedical Application

Abstract

Quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is revolutionizing biodiversity monitoring and ecological assessment by moving beyond simple presence-absence data to deliver quantitative species abundance estimates. This article explores the integration of internal spike-in DNAs as a critical methodological advancement that corrects for technical biases in amplification and sequencing, thereby transforming metabarcoding into a truly quantitative tool. We provide a comprehensive framework covering the foundational principles of the technique, detailed methodological protocols for spike-in implementation, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing performance, and rigorous validation against traditional survey methods. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights the transformative potential of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding for applications ranging from ecosystem health assessment to monitoring environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals.

The Principles and Promise of Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

The field of environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has rapidly evolved, transitioning from simple presence-absence detection to sophisticated quantitative applications. This shift is particularly crucial in biomonitoring, where understanding species abundance and biomass is essential for effective conservation and ecosystem management. Traditional presence-absence data provides limited ecological insights, whereas quantitative approaches enable researchers to track population trends, assess ecosystem health, and evaluate human impacts with unprecedented precision. The integration of internal spike-in DNAs represents a transformative advancement, allowing for correction of technical variations throughout the molecular workflow and generating truly quantitative data. This protocol details comprehensive methodologies for implementing quantitative eDNA metabarcoding approaches, focusing on experimental design, procedural standardization, and data normalization techniques that move beyond basic detection to provide robust abundance metrics [1].

Experimental Protocols for Quantitative eDNA Analysis

Sample Collection and Filtration Protocol

Materials Required:

- Sterile sampling bottles (1-3L capacity)

- Filtration apparatus with pump system

- Filter membranes (1µm and 5µm pore sizes)

- Sterile forceps and gloves

- Sample preservation buffer (e.g., Longmire's buffer, ethanol)

- Cold storage containers for transport

Procedure:

- Collect water samples in sterile containers, avoiding surface disturbance. Take biological replicates (typically 3-5) from each sampling location to account for natural spatial heterogeneity [1].

- Pre-measure water volumes (1L and 3L comparisons) for consistent processing across samples.

- Assemble filtration apparatus using appropriate pore size filters (1µm for microbial communities; 5µm for metazoan/vertebrate targets) [1].

- Filter water samples through designated filter membranes using a peristaltic pump or vacuum system.

- Using sterile forceps, carefully transfer filters to preservation tubes containing appropriate buffer.

- Store samples immediately at -20°C or in liquid nitrogen for transport to laboratory.

- Document filtration time, volume filtered, filter pore size, and preservation method for each sample.

Technical Considerations: Larger pore size filters (5µm) and larger water volumes (3L) maximize the ratio of amplifiable target DNA to total DNA for vertebrate species without compromising absolute detection. For microbial targets, smaller pore sizes (0.22-0.45µm) remain preferable due to smaller particle sizes and higher abundance of microbial DNA in the environment [1].

DNA Extraction and Internal Spike-In Implementation

Materials Required:

- DNA extraction kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater Kit, phenol-chloroform reagents)

- Synthetic internal spike-in DNA (non-competitive, species-specific)

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) instrumentation and reagents

- Spectrophotometer or fluorometer for DNA quantification

- Microcentrifuges and thermal cyclers

Procedure:

- Spike-In DNA Preparation:

- Design synthetic DNA sequences with similar length and GC content to target DNA but containing unique primer binding sites.

- Quantify spike-in DNA accurately using fluorometric methods.

- Create a dilution series to establish standard curves for absolute quantification.

DNA Extraction with Spike-Ins:

- Add known quantities of spike-in DNA to each sample immediately before extraction.

- Extract DNA using standardized protocols (commercial kits or phenol-chloroform methods).

- For vertebrate targets, phenol-chloroform extraction may maximize total DNA recovery but can co-extract inhibitors [1].

- Evaluate extraction efficiency by comparing expected vs. recovered spike-in concentrations.

Quality Assessment:

- Quantify total DNA yield using spectrophotometric methods.

- Assess DNA quality via gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer.

- Aliquot extracted DNA for downstream applications and store at -80°C.

Technical Considerations: Maximizing total DNA yield during extraction does not always increase target detection, as it may concentrate inhibitors and co-extracted off-target DNA. The optimal extraction method should maximize the target-to-total DNA ratio rather than total DNA alone [1].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Methodological Parameters

Table 1: Impact of Filtration Parameters on Target DNA Recovery

| Parameter | Condition | Target DNA Yield | Total DNA Yield | Target:Total Ratio | Inhibition Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Pore Size | 1µm | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

| 5µm | High | Moderate | High | Low | |

| Water Volume | 1L | Low | Low | Moderate | Low |

| 3L | High | High | High | Moderate-High | |

| Filter Material | Cellulose nitrate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Glass fiber | High | High | High | Moderate |

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Vertebrate eDNA

| Extraction Method | Total DNA Yield | Target DNA Recovery | Inhibitor Co-extraction | Processing Time | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform | High | Variable | High | Long | Low |

| Silica Membrane Kit | Moderate | Consistent | Low | Short | Moderate |

| Magnetic Bead Kit | Moderate-High | Consistent | Very Low | Short | High |

Statistical Modeling for Data Integration

The following statistical approach allows inclusion of data from samples collected and processed using different protocols:

Linear Model Framework:

- Develop a normalization model using spike-in recovery rates to correct for technical variations.

- Incorporate protocol-specific correction factors for filter type, volume, and extraction method.

- Account for biological variability through replicate sampling and random effects in mixed models.

Data Integration Equation:

Variance Partitioning:

- Separate technical variance (extraction, amplification) from biological variance (spatial heterogeneity).

- Use coefficient of variation (CV) calculations to assess method precision [1].

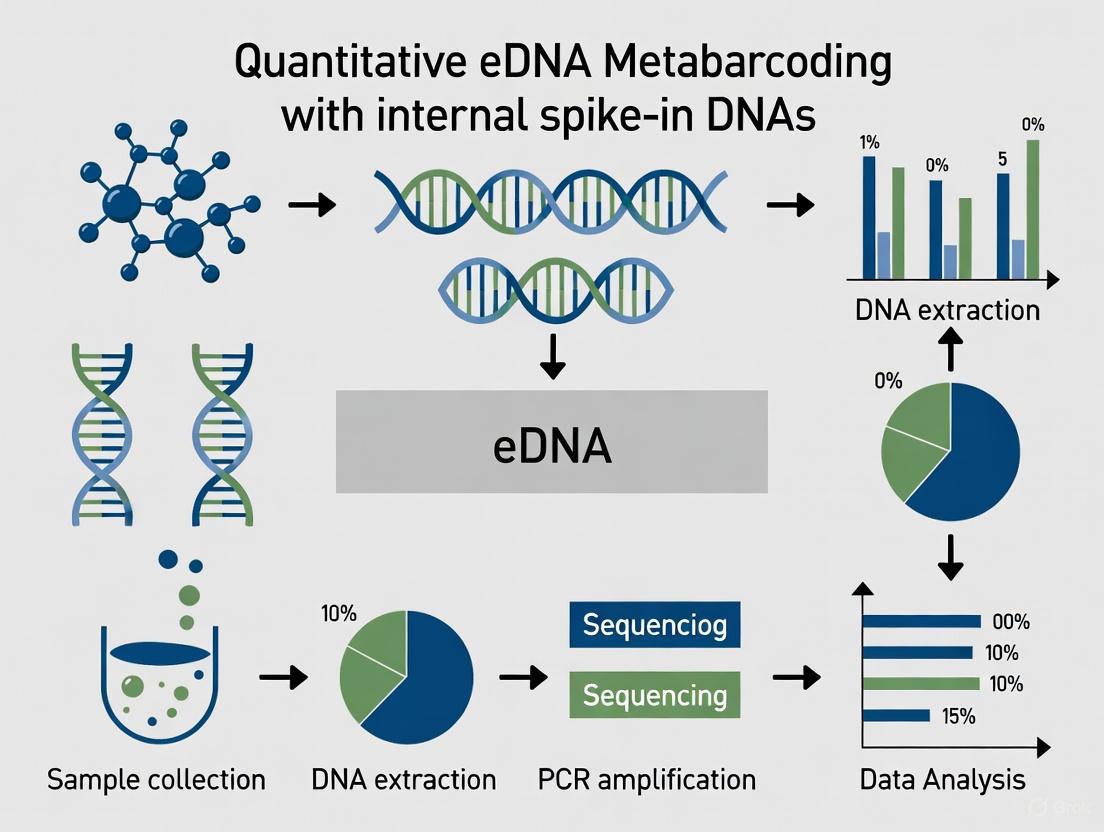

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding Workflow

Internal Spike-In Normalization Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative eDNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Spike-In DNA | Internal standard for quantification | Designed with unique barcodes; non-competitive with target species; added pre-extraction |

| Filter Membranes (5µm) | Particle capture for vertebrate eDNA | Optimized for metazoan DNA recovery; reduces microbial DNA background |

| Inhibition Resistance PCR Mix | Enhanced amplification efficiency | Critical for complex environmental samples; reduces false negatives |

| DNA Preservation Buffer | Biomolecule stabilization | Long-term integrity of eDNA; compatible with downstream applications |

| Quantitative PCR Reagents | Absolute quantification | Standard curves for spike-in and target DNA; high precision required |

| Metabarcoding Primers | Taxon-specific amplification | Designed for complementary regions; validated for quantitative recovery |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Data processing and normalization | Custom scripts for spike-in normalized quantification; open-source options available |

| 2-Methylbutyrylglycine-d9 | 2-Methylbutyrylglycine-d9 Deuterated Standard | 2-Methylbutyrylglycine-d9 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for RUO quantification of 2-MBG in metabolic disorder research. For Research Use Only. |

| 1,7-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hept-1-en-3-one | 1,7-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hept-1-en-3-one, MF:C19H20O3, MW:296.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The implementation of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with internal spike-in DNAs represents a paradigm shift in biomonitoring capabilities. By moving beyond simple presence-absence data, researchers can now generate abundance metrics that provide deeper ecological insights and more robust environmental assessments. The protocols outlined herein emphasize methodological standardization while acknowledging the need for flexibility in protocol selection based on specific research questions and target organisms. Future developments in synthetic spike-in design, multi-species quantification approaches, and integrated bioinformatic pipelines will further enhance the precision and applicability of quantitative eDNA methods. As the field continues to evolve, the framework presented here provides a foundation for generating comparable, reproducible quantitative data across studies and ecosystems, ultimately supporting more effective conservation and management decisions.

Internal spike-in DNAs are known quantities of exogenous or synthetic DNA sequences added to biological samples to serve as an internal reference for quantitative normalization. In quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding, they function as a critical quality control tool, enabling researchers to calibrate measurements, account for technical biases introduced during sample processing, and transition from relative to absolute abundance estimates. This protocol outlines the fundamental principles, implementation workflows, and key applications of spike-in DNAs, providing a framework for their use in robust and reproducible eDNA-based biomonitoring.

In molecular biology, particularly in sequencing-based assays, the accurate quantification of target molecules is often hampered by numerous technical variabilities. Internal spike-in DNAs are known quantities of molecules—such as oligonucleotide sequences—added to a biological sample to act as an internal reference for the quantitative estimation of the molecule of interest across samples and batches [2]. Their primary role is to correct for technical and biological biases introduced during sample processing, including DNA extraction, library preparation, handling, and sequencing [2].

Within the specific context of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding, the use of spike-in controls has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome the limitations of standard read-count normalization. In metabarcoding, the total DNA signal can vary significantly between samples due to biological reasons (e.g., differences in total biomass) or technical artifacts. Normalizing by total read count can introduce severe biases and lead to misleading biological interpretations [3]. Spike-in controls, added at the very beginning of the workflow, experience the same technical processes as the endogenous eDNA. The discrepancy between the known amount of spike-in added and the finally measured amount provides a sample-specific scaling factor that can be applied to the native eDNA data, thereby improving the accuracy of inter-sample comparisons and enabling absolute quantification [4].

The Working Principle and Normalization Strategy

The core principle of spike-in DNAs is based on their use as an internal standard. A precise, known quantity of spike-in DNA is added to each sample during the initial processing steps. Following sequencing and bioinformatic analysis, the recovery rate of the spike-in sequences is calculated. This recovery rate directly reflects the cumulative technical efficiency and bias of the entire workflow for that specific sample.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the typical lifecycle of a spike-in control within a sample, from addition to final data normalization:

The normalization process typically involves deriving a sample-specific scaling factor. A common approach involves determining the ratio between the observed spike-in read counts and the expected counts. For instance, if a sample yields fewer spike-in reads than expected, its endogenous gene counts are scaled upwards, under the assumption that the lower spike-in recovery reflects a global technical loss for that sample [2]. More sophisticated methods may use regression analysis or factor analysis across multiple spike-ins added at various concentrations to model the relationship between input amount and sequencing output for a more robust estimate of technical bias [2].

Types of Spike-Ins and Research Reagent Solutions

The choice of spike-in type depends on the experimental goals, the required precision, and practical considerations regarding availability and cost. The table below summarizes the three main types of DNA spike-ins used in metabarcoding studies:

Table 1: Comparison of Primary DNA Spike-In Types for Metabarcoding

| Spike-In Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Spike-Ins [4] | Whole organisms or intact cells from a different species (e.g., Drosophila cells added to human samples). | Contains a diverse, natural set of target epitopes; easy to integrate into workflows. | Input DNA amount is difficult to control and quantify precisely; long-term supply can be challenging. |

| DNA Spike-Ins [4] | Pre-amplified marker DNA from a non-target organism. | Allows for more precise measurement of input material than biological spike-ins. | The original biological source is finite; potential for degradation; difficult to recreate if lost. |

| Synthetic Spike-Ins [4] | Artificial DNA molecules designed in silico and commercially synthesized. | Can be precisely quantified; sequence is customizable; can be resynthesized infinitely; easily distinguished from sample DNA. | Requires careful design and synthesis; may not perfectly mimic all properties of natural DNA. |

The selection of the appropriate spike-in is a critical decision. Synthetic spike-ins are increasingly recommended for long-term monitoring projects due to their infinite reproducibility and precise quantifiability [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of a spike-in protocol relies on key reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Spike-In Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic DNA Fragments [4] | Custom-designed, artificially generated DNA sequences that serve as the spike-in standard. | Designed to be amplified by the same universal primers as the target eDNA but be unique enough for bioinformatic separation. |

| Universal Primers [5] | Primer sets that amplify a standardized, taxonomically informative gene region from both the sample eDNA and the spike-in. | The MiFish-U primer set is a universal primer for fish eDNA metabarcoding [5]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [3] | PCR enzyme with proofreading activity to minimize amplification errors during library preparation. | Critical for accurate amplification of both spike-in and sample sequences in quantitative assays. |

| Quantitative Standard [3] | A pre-quantified sample of the spike-in DNA used to create a dilution series for a standard curve. | Used in qPCR to absolutely quantify the spike-in DNA before it is added to experimental samples. |

| External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) Spike-Ins [2] | A well-known set of synthetic spike-in standards developed for RNA-seq that exemplifies the principle for DNA-based assays. | Serves as a model for designing and implementing complex spike-in mixtures for DNA metabarcoding. |

Quantitative Evidence and Validation

The utility of spike-in normalization is not merely theoretical; it is backed by empirical evidence demonstrating its superiority over conventional normalization methods. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from selected studies that validate the spike-in approach:

Table 3: Quantitative Evidence Supporting Spike-In Normalization

| Study Context | Spike-In Method | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish Community Monitoring [5] | qMiSeq (using internal standard DNAs) | Significant positive relationships were found between eDNA concentrations quantified by qMiSeq and both abundance (R² values provided) and biomass of captured fish across 21 river sites. | Demonstrated that spike-in normalized eDNA metabarcoding is a suitable tool for quantitative monitoring of fish communities. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) [6] | ChIP-Rx (using exogenous chromatin) | In a titration of H3K79me2 levels over a 10-fold range, spike-in normalization correctly quantified enrichment across the signal intensity range, whereas read-depth normalization failed. | Showed spike-in normalization provides accurate quantification across a wide dynamic range where standard methods fail. |

| R-loop Mapping (DRIP-seq) [3] | Synthetic RNA-DNA hybrids & Drosophila cellular spike-ins | After global transcription inhibition, read-count normalization created an artifactual increase in signal at the 3' ends of long genes. Spike-in normalization corrected this, showing no change, which was validated by DRIP-qPCR. | Highlighted that without spike-in normalization, global changes in total target content can lead to severe misinterpretations. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Implementing Synthetic Spike-Ins for eDNA Metabarcoding

This protocol is adapted from recommendations for insect metabarcoding using the COI gene, a common practice that can be adapted for other target taxa [4].

- Spike-in Design: Design one or more synthetic DNA sequences in silico that:

- Contain the binding sites for your universal metabarcoding primers (e.g., MiFish-U for fish [5]).

- Are highly divergent from any natural sequence in public databases to prevent misidentification. A BLAST search is essential.

- Are of a length similar to the expected amplicon from the native eDNA.

- Spike-in Synthesis: Commission the synthesis and cloning of the designed sequence(s) from a commercial vendor. Receive the product typically as a plasmid in a bacterial stock.

- Spike-in Quantification:

- Isolate the plasmid and linearize it.

- Quantify the DNA concentration accurately using a fluorometer. Calculate the exact copy number/µL based on the molecular weight.

- Serially dilute the stock to create a working solution of known concentration (e.g., 10^8 copies/µL).

- Spike-in Addition: Add a fixed, small volume (e.g., 2 µL) of the working solution to each eDNA sample extract immediately after extraction and before any amplification steps. The amount added should be within the same order of magnitude as the expected target eDNA to be quantitatively meaningful. Vortex thoroughly.

- Metabarcoding PCR and Sequencing: Proceed with standard library preparation using your universal primers. The spike-in sequences will be co-amplified with the native eDNA.

- Bioinformatic Separation:

- Process the raw sequencing data through your standard pipeline (e.g., quality filtering, denoising).

- Using a reference file of the synthetic spike-in sequence(s), separate the spike-in-derived Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) from the native eDNA ASVs.

- Normalization Calculation and Application:

- For each sample, calculate the normalization factor (NF). A simple method is:

NF_sample = (Total Spike-in Reads in Sample) / (Average Total Spike-in Reads across all Samples) - Divide the read count of each native eDNA ASV in a sample by the NF for that sample to obtain the normalized abundance.

- For each sample, calculate the normalization factor (NF). A simple method is:

Protocol B: Using a Cellular Spike-In for DRIP-Seq

This protocol details the use of Drosophila melanogaster cells as a spike-in for DNA-RNA Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (DRIP-seq), a method applicable to other chromatin studies [3].

- Spike-in Cell Culture: Maintain a culture of Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells under standard conditions.

- Sample and Spike-in Mixing:

- Harvest the human (or target) cells and the Drosophila cells by centrifugation.

- For each experimental sample, mix a fixed number of Drosophila cells (e.g., 1 x 10^6 cells) with a fixed number of human cells (e.g., 10 x 10^6 cells). The ratio should be consistent across all samples.

- Co-pellet the mixed cells.

- Chromatin Preparation and DRIP: Isolate chromatin from the mixed cell pellet according to your standard DRIP or ChIP protocol [3]. The key is that the Drosophila chromatin is subjected to the exact same conditions (lysis, sonication/shearing, immunoprecipitation with the S9.6 antibody, etc.) as the human chromatin.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries from the immunoprecipitated DNA and sequence on an appropriate platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis and Normalization:

- Align the sequencing reads to a combined reference genome (e.g., human + Drosophila).

- Separate the reads aligning to the Drosophila genome.

- Identify a set of high-confidence peaks from the Drosophila signal.

- Sum the reads mapping within these Drosophila peaks for each sample.

- Calculate a normalization factor for each sample based on the total Drosophila reads (or peak reads), for example, using the median of ratios method [3]. Apply this factor to the reads mapping to the human genome.

Internal spike-in DNAs are no longer a niche tool but a fundamental component for rigorous quantitative eDNA metabarcoding and other sequencing applications. By providing an internal reference that travels with the sample through the entire workflow, they empower researchers to distinguish technical noise from biological signal, compare data across different batches and studies, and move beyond simple presence-absence data towards meaningful absolute abundance estimates. The adoption of standardized spike-in protocols, particularly using sustainable synthetic standards, is a critical step towards achieving comparability and standardization in global biomonitoring efforts [4]. As the field advances, the integration of spike-ins will be paramount for generating the high-fidelity, quantitative data necessary to understand and manage ecosystems effectively.

The simultaneous conservation of species richness and evenness is paramount for effectively reducing biodiversity loss and maintaining ecosystem health [7]. Traditional methods for biomonitoring, such as direct capture and visual census, provide valuable data but are often constrained by the requirement for significant effort, time, and taxonomic expertise [7]. Furthermore, these methods can be invasive, potentially damaging fragile populations of endangered species and their habitats [7]. Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has emerged over the past decade as a powerful, non-invasive alternative for detecting organisms through the cellular materials they shed into their environment [7].

Environmental DNA analysis for macroorganisms primarily utilizes two technical methods: species-specific detection and DNA metabarcoding. The species-specific approach, often using quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a established method for absolute quantification but is limited in scope. The development of species-specific assays is time-consuming, costly, and requires prior knowledge of the species present in a study area, making it unsuitable for the simultaneous quantitative assessment of multiple, unexpected species in a community [7]. In contrast, eDNA metabarcoding, which uses universal primers and high-throughput sequencing, allows for the comprehensive identification of community composition across multiple taxa [7] [8]. However, a significant challenge has been that the sequence read counts generated are not directly quantitative. These read counts can be skewed by PCR amplification biases, primer mismatches, and library preparation artifacts, preventing them from reliably representing the true biomass or abundance of species in the environment [7] [8]. The qMiSeq approach was developed to bridge this critical gap, transforming metabarcoding from a primarily qualitative tool into one capable of absolute quantification [7].

The qMiSeq Approach: Principle and Workflow

The quantitative MiSeq sequencing (qMiSeq) approach is a novel method that enables the conversion of sequence read numbers into absolute DNA copy numbers [7]. Its core innovation lies in the use of internal standard DNAs that are spiked into each sample at known concentrations before PCR amplification. This allows for the creation of a sample-specific standard curve, which accounts for technical variations that occur during the analytical process.

The principle of qMiSeq is based on generating a linear regression between the known copy numbers of the internal standards and the sequence reads they generate in each sample [7]. The resulting regression coefficient is then used to convert the sequence reads of detected native taxa in that same sample into estimated DNA copy numbers. This controls for sample-specific effects like PCR inhibition and library preparation bias, which are major hurdles for quantitative metabarcoding [7]. A standard curve is essential in quantitative PCR methods to determine unknown target concentrations [9], and qMiSeq adapts this robust principle for a high-throughput sequencing context.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key procedural steps in a qMiSeq experiment, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Key Advantages of the Internal Standard Method

The use of internal standards differentiates qMiSeq from conventional metabarcoding and provides its quantitative power. The internal controls allow for estimating the expected initial copy number of the target by accounting for the variable efficiency of the PCR amplification and other preparatory steps [10]. The internal standard method is designed to yield approximately unbiased answers, provided that the key assumptions of the technique are met, such as equivalent amplification efficiency between standards and target molecules [10]. This method provides a means to control for the exponential nature of PCR, where small variations in amplification efficiency can lead to large differences in the final product yield [11].

Experimental Validation and Key Quantitative Data

The performance of the qMiSeq approach as a quantitative monitoring tool has been rigorously validated through controlled studies. One such study compared eDNA concentrations quantified by qMiSeq with the results of traditional capture surveys using an electrical shocker across 21 sites in four rivers in Japan [7]. The findings demonstrated a significant positive relationship between the eDNA concentrations of each species quantified by qMiSeq and both the abundance and biomass of each captured taxon at the study sites [7].

The table below summarizes the key quantitative relationships observed in this validation study.

Table 1: Summary of Validation Results Comparing qMiSeq with Capture Surveys

| Comparison Metric | Relationship Observed | Statistical Significance | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| eDNA conc. vs. Abundance/Biomass | Significant positive relationship | P-value < 0.05 | Multi-species data within sites [7] |

| eDNA conc. vs. Abundance/Biomass | Significant positive relationship for 7 out of 11 taxa | P-value < 0.05 | Within individual taxa across multiple sites [7] |

| Species Richness | qMiSeq consistently detected more species than capture surveys | N/A | At 16 out of 21 sites, no false negatives occurred [7] |

| qMiSeq vs. qPCR | Significant positive relationship for 3 tested taxa | P < 0.001, R² = 0.81-0.99 | Validation against an established quantitative method [7] |

This validation confirms that the qMiSeq approach can produce biologically meaningful quantitative data. The high correlation with both capture survey data and independent qPCR assays underscores its reliability and potential to replace or supplement more invasive and labor-intensive methods.

Detailed qMiSeq Protocol

This section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol for implementing the qMiSeq approach for the absolute quantification of fish communities from water samples.

Sample Collection and Filtration

- Water Collection: Collect water samples in sterile containers from the target environment (e.g., river, lake, marine water). The volume collected should be standardized; 1-2 liters is common for freshwater systems. Field blanks (e.g., ultra-pure water transported to the field) should be included to control for contamination.

- Filtration: Filter water samples through sterile membrane filters (e.g., mixed cellulose ester, glass fiber) with a pore size of 0.2 to 1.0 µm to capture eDNA particles. The choice of filter material and pore size may be optimized for the specific environmental matrix and biomass load.

- Preservation: Preserve the filters immediately after filtration. They can be stored frozen at -20°C or in a preservation buffer (e.g., Longmire's buffer, ethanol) to prevent DNA degradation.

DNA Extraction and Internal Standard Addition

- Extraction: Extract DNA from the filters using a commercial DNA extraction kit suitable for environmental filters. Follow the manufacturer's protocol, but include negative extraction controls (reagents only) to monitor for contamination.

- Internal Standard Spike-In: After extraction, spike a known quantity of synthetic internal standard DNAs into each sample extract. These standards should be non-competitive, artificial sequences that are amplified by the same universal primers but are distinguishable bioinformatically. A dilution series of at least 3-5 different concentrations is recommended to construct a robust standard curve [7]. The exact copy number of each standard must be known.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Amplification: Perform a PCR amplification on the sample-spike mix using universal primers targeting the taxonomic group of interest (e.g., the MiFish-U primer set for fish [7]). The PCR conditions (annealing temperature, cycle number) should be optimized to minimize bias and maximize specificity.

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified products according to the requirements of the chosen high-throughput sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq/iSeq). This typically involves a second, limited-cycle PCR to add platform-specific adapter sequences and sample-indexing barcodes to allow for multiplexing.

- Sequencing: Pool the indexed libraries in equimolar concentrations and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., iSeq for smaller studies, MiSeq for larger ones). The sequencing run should generate a sufficient number of reads to cover all samples and expected diversity without being saturated.

Data Analysis and Absolute Quantification

- Bioinformatics: Process the raw sequence data through a standard metabarcoding pipeline. This includes demultiplexing, quality filtering (e.g., using QIIME2 or DADA2), merging paired-end reads, and clustering sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment is performed by comparing these units to a reference database.

- Standard Curve Generation: For each sample, plot the known copy numbers of the internal standards against their obtained sequence reads. Perform a linear regression analysis to derive the sample-specific coefficient (slope) for converting reads to copies [7].

- Absolute Quantification: Apply the sample-specific regression coefficient to the sequence read counts of all biologically relevant taxa detected in that sample. This calculation yields the estimated absolute DNA copy number for each taxon in the original sample. The conceptual relationship between the internal standards and the quantitative result is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the qMiSeq approach requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details the key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for the qMiSeq Approach

| Item | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers (e.g., MiFish-U) | To amplify a standardized DNA barcode region from all target taxa (e.g., fish) in the community. | Must be broadly conserved across the taxonomic group while providing sufficient taxonomic resolution [7]. |

| Internal Standard DNAs | Artificial DNA sequences used to generate a sample-specific standard curve for converting reads to copy numbers. | Must be amplifiable by the universal primers but distinct from natural sequences; copy numbers must be precisely known [7]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | To amplify the target eDNA fragments with minimal errors during PCR. | Low error rate is critical for accurate sequence data. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate and purify eDNA from environmental filters. | Should be optimized for low-biomass, inhibitor-rich environmental samples. |

| Library Preparation Kit | To prepare amplicon libraries for high-throughput sequencing by adding indexes and adapters. | Compatibility with the chosen sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina) is essential. |

| Negative Controls | To monitor for contamination at all stages (field, extraction, PCR). | Crucial for distinguishing true signals from contamination and ensuring data integrity [7]. |

| (R,E)-Deca-2-ene-4,6-diyne-1,8-diol | (R,E)-Deca-2-ene-4,6-diyne-1,8-diol, MF:C10H12O2, MW:164.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Dehydroxy-8-hydroxygaleopsinolone | 6-Dehydroxy-8-hydroxygaleopsinolone, MF:C20H28O3, MW:316.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

Critical Parameters for Success

- Internal Standard Design and Quality: The internal standards are the cornerstone of quantification. They must be designed to have identical primer binding sites to the natural targets and should be amplified with an efficiency as close as possible to that of the natural eDNA [9]. Their concentration must be determined with high accuracy, using spectrophotometry and subsequent calculation of copy numbers based on molecular weight [9].

- Baseline and Threshold Settings in qPCR Validation: When using qPCR for validation or parallel analysis, accurate data analysis is vital. The baseline fluorescence should be set correctly using early amplification cycles to avoid distorting the Cq values. The threshold should be set within the exponential phase of all parallel amplifications where the curves are parallel, ensuring accurate relative quantification between samples [12].

- Reference Database Completeness: A false negative in metabarcoding can occur due to a lack of reference sequences in the database [7]. It is critical to use a comprehensive and curated reference database for the target region and taxonomic group to minimize taxonomic misassignment and false negatives.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low Correlation with Biomass: If the quantitative relationship is weak, investigate potential primer bias by testing different primer sets or using mock communities. Ensure that the internal standard amplification efficiencies are consistent and that the standard curve has a high coefficient of determination (R²).

- High Variation Among Replicates: This can be caused by incomplete mixing of internal standards, inhibitor contamination in some samples, or uneven distribution of eDNA in the environment. Ensure thorough homogenization of samples and standards, and consider pre-treating extracts to remove inhibitors.

- False Positives/Negatives: Contamination can cause false positives, which can be identified and controlled for with rigorous negative controls. False negatives can result from PCR inhibition, primer mismatch, or low eDNA concentration. Dilution of the extract or the use of inhibitor removal kits can help alleviate inhibition.

The qMiSeq approach represents a significant leap forward in the field of eDNA analysis, successfully addressing the long-standing challenge of quantification in metabarcoding. By integrating the principles of internal standardization with high-throughput sequencing, it allows researchers to move beyond simple species lists and obtain absolute estimates of DNA copy numbers that correlate strongly with traditional measures of abundance and biomass [7]. This protocol provides a detailed guide for implementing this powerful method, from sample collection to data analysis. As with any quantitative molecular method, attention to detail, rigorous control measures, and careful validation are essential for generating reliable and impactful data. The qMiSeq approach holds immense promise for advancing quantitative ecological monitoring, conservation biology, and the study of community dynamics in a wide range of ecosystems.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a powerful tool for biodiversity monitoring, yet its quantitative application has been limited by methodological constraints including PCR inhibition and library preparation bias. The integration of internal spike-in DNA standards represents a transformative approach that directly addresses these limitations. This technical review examines the mechanistic basis of how synthetic spike-ins and standardized protocols enable correction for sample-specific inhibition and preparation artifacts, facilitating a transition from relative to absolute quantification in eDNA studies. We provide detailed methodologies, validation data, and practical implementation frameworks to support researchers in adopting these advanced quantitative approaches.

The potential of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding to revolutionize biodiversity monitoring has been constrained by two persistent technical challenges: PCR inhibition and library preparation bias. PCR inhibition occurs when environmental co-contaminants such as humic acids, tannins, or heavy metals reduce or block polymerase activity, leading to false negatives and skewed community representation [13]. Library preparation bias emerges from differential amplification efficiency during PCR, primer binding affinity variations, and stochastic effects during sequencing library construction, ultimately distorting the relationship between original DNA template quantities and final sequencing read counts [14] [8].

The integration of internal spike-in DNA standards represents a paradigm shift in addressing these challenges. By adding known quantities of synthetic DNA to each sample prior to processing, researchers can create sample-specific calibration curves that account for technical variation, thereby recovering quantitative information that would otherwise be lost [4]. This approach transforms metabarcoding from a primarily qualitative tool into a robust quantitative methodology capable of generating absolute abundance data critical for ecological monitoring, conservation assessment, and management decisions.

The qMiSeq Approach: A Framework for Quantitative Accuracy

The quantitative MiSeq (qMiSeq) approach has emerged as a particularly effective methodology for overcoming quantification barriers in eDNA metabarcoding. This technique employs internal standard DNAs to establish sample-specific linear regressions between known DNA copy numbers and observed sequence reads, enabling conversion of raw read counts to estimated DNA copy numbers while accounting for inhibition and bias [5].

Mechanistic Workflow and Advantages

The qMiSeq protocol incorporates internal standards at the DNA extraction or immediately post-extraction stage, allowing them to experience the same technical challenges as the target eDNA throughout the entire workflow. The relationship between the known quantity of spike-ins and their resulting sequence reads creates a transformation metric that can be applied to all other sequences in the sample [5] [4].

Key advantages of this approach include:

- Sample-specific calibration: Each sample receives its own correction factor, accounting for variation in inhibition levels across different environmental contexts

- Process integration: Spike-ins experience the entire workflow from extraction through sequencing, capturing bias sources at multiple stages

- Absolute quantification potential: When properly implemented, the approach can transition from relative abundance to absolute copy number estimation

- Quality control: Abnormal spike-in recovery patterns flag problematic samples requiring re-processing

The effectiveness of this methodology is demonstrated by validation studies showing significant positive relationships between eDNA concentrations quantified by qMiSeq and both abundance (R² = 0.81) and biomass (R² = 0.99) of captured fish taxa in river systems [5].

Visualizing the qMiSeq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the qMiSeq approach with internal spike-in standards:

This workflow demonstrates how spike-in standards are integrated throughout the process, with the calibration step specifically addressing the major technical variation sources including PCR inhibition, library preparation bias, and primer binding bias.

Quantitative Validation: Comparative Performance Metrics

Rigorous validation studies have demonstrated the quantitative capabilities of spike-in corrected eDNA metabarcoding approaches. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from experimental evaluations.

Method Comparison and Performance

Table 1: Comparative analysis of eDNA quantification methods with and without spike-in standardization

| Method | Technical Challenge Addressed | Correlation with Biomass | Limitations | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qMiSeq with spike-ins | PCR inhibition & library prep bias | R² = 0.81-0.99 [5] | Requires optimized spike-in concentration | Absolute quantification in inhibited samples |

| Relative read abundance (RRA) | None | R² = 0.52 ± 0.34 [8] | Highly susceptible to technical bias | Qualitative community profiling |

| Species-specific qPCR | PCR inhibition (via standard curve) | High for single species [5] | Limited to predefined targets | Single species detection/quantification |

| CTAB-PCI isolation | Inhibitor removal [13] | Not directly assessed | Does not address library prep bias | Samples with high tannin/humic acid content |

Buffer and Isolation Method Efficacy

Table 2: Performance comparison of eDNA isolation and storage methods for inhibition reduction

| Method | Storage Buffer | Isolation Technique | eDNA Yield (copies/µL) | Inhibition Reduction | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB-PCI | CTAB | Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | 933.7 [13] | High | Moderate |

| Long-PCI | Longmire's | Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | 0.6 (pre-IRK), 927.8 (post-IRK) [13] | Moderate (requires IRK) | Moderate |

| Long-CTAB-CI | Longmire's | CTAB + Chloroform:Isoamyl | 206.6 (pre-IRK), 406.3 (post-IRK) [13] | Low-Moderate | High |

| Multi-filter PCI | CTAB or Longmire's | Multi-filter PCI | 6.39 (vs 1.4 single filter) [13] | High (via dilution) | Low |

Experimental Protocols: Implementation Frameworks

Synthetic Spike-in Design and Implementation

The development and application of synthetic spike-ins follows a systematic protocol to ensure optimal performance:

Spike-in Design Criteria:

- Sequence composition: Artificial DNA sequences designed in silico with no significant similarity to natural sequences in public databases [4]

- Length matching: Spike-in amplicon size should approximate target amplicon sizes (e.g., 300-500 bp for COI markers)

- Primer binding regions: Perfect match to metabarcoding primers while maintaining unique internal sequence

- Concentration optimization: Empirical testing to determine optimal spiking concentration that doesn't compete with target DNA

Implementation Protocol:

- Spike-in addition: Add synthetic spike-ins to each sample immediately after DNA extraction or during extraction buffer addition

- Quantity calibration: Use precisely quantified spike-in mixtures across a concentration range covering expected eDNA quantities

- Processing: Co-amplify spike-ins and native eDNA using standard metabarcoding PCR protocols

- Bioinformatic separation: Identify spike-in sequences using exact matching or dedicated database

- Normalization calculation: Derive sample-specific correction factors based on expected vs. observed spike-in reads

- Data transformation: Apply correction factors to all taxonomic assignments in the sample

qMiSeq Wet Laboratory Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Synthetic spike-in DNA mixtures (commercially synthesized or in-house prepared)

- Metabarcoding primers with appropriate adapter sequences

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase with proofreading capability

- Size-selection magnetic beads (e.g., SPRIselect)

- Library quantification kit (e.g., Qubit, qPCR-based)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Processing:

- Filter water samples through appropriate pore size membranes (typically 0.22-1.2 μm)

- Extract DNA using CTAB-based buffer systems for inhibitor-rich environments [13]

- Add synthetic spike-in DNA to each extract at predetermined concentrations

Library Preparation:

- Perform first-round PCR with metabarcoding primers containing partial adapter sequences

- Use minimal PCR cycles (typically 25-35) to reduce amplification bias

- Clean amplified products with size-selection beads

- Conduct second-round PCR to add complete Illumina adapter sequences and dual indices

- Pool purified libraries in equimolar ratios based on qPCR quantification

Sequencing and Data Processing:

- Sequence on Illumina platform (iSeq, MiSeq, or NovaSeq) with appropriate read length

- Demultiplex sequences based on dual indexing to minimize index hopping

- Generate sample-specific correction factors from spike-in read counts

- Apply corrections to convert raw read counts to estimated DNA copy numbers

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for implementing quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with internal standards

| Reagent/Material | Function | Implementation Notes | Commercial Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic spike-in DNA | Internal standard for quantification | Custom designed; add post-extraction | Integrated DNA Technologies, Twist Bioscience |

| CTAB buffer | Inhibition reduction during storage | Particularly effective for tannin-rich waters | Sigma-Aldrich C-5730, custom formulation |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | Organic extraction for inhibitor removal | Requires appropriate safety protocols | Thermo Fisher 17928, Sigma-Aldrich 77617 |

| Size-selection magnetic beads | Library purification and size selection | Enable removal of primer dimers | Beckman Coulter SPRIselect, MagBio SeraMag |

| High-fidelity DNA polymerase | Reduced amplification bias in PCR | Proofreading activity improves accuracy | Thermo Fisher Platinum SuperFi, NEB Q5 |

| Dual-indexed adapters | Sample multiplexing | Reduce index hopping compared to single indexing | Illumina IDT for Illumina, NEB Nextera |

The integration of internal spike-in standards represents a fundamental advancement in eDNA metabarcoding, directly addressing the critical challenges of PCR inhibition and library preparation bias that have limited the quantitative potential of this methodology. The qMiSeq approach and related frameworks provide a robust pathway toward absolute quantification, enabling researchers to move beyond simple presence-absence data to generate meaningful abundance metrics that reflect true biological patterns.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on increasing the multiplexing capabilities of spike-in systems, allowing for simultaneous quantification of multiple taxonomic groups through customized standard sets. Additionally, the integration of automated liquid handling systems for spike-in addition will improve reproducibility and reduce technical variation. As these methods become standardized and widely adopted, they will transform eDNA metabarcoding into a truly quantitative tool capable of addressing fundamental questions in ecology, conservation biology, and environmental management.

Application Notes: Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding Across Sectors

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is a revolutionary method for assessing biodiversity by analyzing genetic material shed by organisms into their environment [15]. This approach involves collecting environmental samples (water, sediment, air), extracting DNA, amplifying it with universal primers, and sequencing it with next-generation technologies to identify multiple species simultaneously [15] [16]. When combined with internal spike-in DNAs—synthetic DNA sequences of known quantity added to samples prior to processing—this technique transitions from qualitative detection to robust quantitative assessment, enabling precise biomass estimation and comparative analysis across samples [17].

The table below summarizes the core applications of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding across the key sectors of fisheries management and environmental biomonitoring.

Table 1: Core Applications of Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

| Field | Specific Application | Quantitative Measure | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fisheries Management [17] | Stock assessments | Population biomass and trends over time [17] | Non-invasive, cost-effective, and scalable population monitoring [17]. |

| Fisheries Management [17] | Distribution mapping | Species presence/absence across regions [17] | Provides a link between eDNA concentration and species abundance [17]. |

| Environmental Biomonitoring [15] [18] | Biodiversity surveys | Species richness and community composition [15] | Efficient, non-invasive detection of a broad spectrum of taxa, including rare and elusive species [15] [19]. |

| Environmental Biomonitoring [20] | Ecosystem health/pollution assessment | Abundance shifts in microbial and eukaryotic communities [20] | Identifies potential pathogens and pollution-indicative organisms to guide conservation [20]. |

| Environmental Biomonitoring [15] [19] | Trophic interaction studies | Relative frequency of prey items in diet analysis [19] | Unravels food webs and predator-prey interactions without direct observation [15]. |

Fisheries Stock Assessment

Integrating eDNA metabarcoding into fisheries stock assessments requires a clear quantitative link between eDNA data and population metrics. The foundational principle is that more fish shed more DNA, creating a correlation between eDNA concentration in water samples and species abundance or biomass [17]. The key challenge is moving from simple detection to generating a population index that can track changes over multiple years for management models [17]. Internal spike-in DNAs are critical here, as they control for technical variability during DNA extraction and amplification, allowing scientists to convert raw sequence read counts into calibrated, comparable estimates of relative biomass.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Assessment

In ecological assessments, quantitative eDNA metabarcoding offers a powerful tool for characterizing communities and detecting anthropogenic impacts. For instance, research in the Perak River, Malaysia, used eDNA to identify 4,045 bacterial and 3,422 eukaryotic Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), with specific abundance patterns of certain organisms suggesting organic and heavy metal pollution [20]. Similarly, analysis of foraminiferal eDNA in Indian estuaries revealed a predominance of soft-bodied monothalamous species often overlooked by traditional morphological surveys, providing a more complete picture of diversity and serving as a baseline for biomonitoring [21]. The use of spike-ins in such studies ensures that comparisons of alpha diversity (diversity within a single sample) and beta diversity (differences in composition between samples) are accurate and not biased by technical noise [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Water Sample Collection and Filtration for Fisheries Assessment

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used for aquatic monitoring and stock assessment [17] [20].

Application: Targeted to collect eDNA for quantifying fish population biomass and distribution. Principle: Genetic material shed by fish (e.g., via scales, mucus, feces) is captured from the water column, concentrated via filtration, and preserved for downstream molecular analysis [17].

Table 2: Reagents and Equipment for Water Sample Collection and Filtration

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Consumables | Sterile sample bottles | 1 L capacity, for collecting water with minimal contamination [20]. |

| Consumables | Filter membrane | Cellulose nitrate membrane, 0.45 µm pore size, to capture eDNA particles [20]. |

| Consumables | DNA preservation buffer | e.g., Longmire's buffer, CTAB, or commercial kits; stabilizes DNA until extraction. |

| Equipment | Vacuum pump | Oil-free pump (e.g., Rocker 300) for consistent filtration pressure [20]. |

| Equipment | Filter holder and flask | To support the filter membrane during the filtration process. |

| Safety & QC | Clean spatulas/forceps | Autoclaved, single-use tools to handle filters and avoid cross-contamination [19]. |

| Safety & QC | Negative control | 1 L of distilled water, processed alongside samples to monitor for contamination [20]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Collect water samples from predetermined stations using sterile 1L bottles [20].

- For flowing water, open the bottle against the current to collect an integrated sample.

- Record in-situ environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) as these can influence eDNA degradation and distribution [21].

- Sample Transportation and Storage:

- Transport samples to the laboratory on ice and process within 12-24 hours to minimize DNA degradation [20].

- Filtration and Preservation:

- Set up the filtration apparatus with a 0.45 µm cellulose nitrate membrane [20].

- Filter the water sample using an oil-free vacuum pump.

- Using sterile forceps, carefully fold the filter membrane and place it in a sterile tube. Immediately preserve it in an appropriate DNA preservation buffer or freeze at -20°C until DNA extraction [20].

- Control Processing:

- Process the negative control (distilled water) through the exact same filtration and preservation steps to identify any potential contamination introduced during the process [20].

Protocol 2: Laboratory Workflow for Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

This core protocol details the steps from DNA extraction to sequencing, with a critical emphasis on the incorporation of internal spike-in DNAs for quantification.

Application: Essential for all quantitative eDNA studies, enabling the determination of species composition and relative abundance in a sample. Principle: Internal spike-in DNAs are synthetic, known sequences added in a fixed quantity to each sample after collection but before DNA extraction. They correct for variations in extraction efficiency and PCR amplification bias, allowing for the normalization of sequence data and more accurate inter-sample comparisons.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for eDNA Metabarcoding

| Reagent/Solution | Critical Function | Example Types & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Spike-in DNA | Acts as an internal standard for quantification; corrects for technical variability in extraction and amplification. | Synthetic, non-biological DNA sequences (e.g., from synthetic organisms like Pseudomonas syringae pathway tagetis). Must be absent from the study environment. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates and purifies DNA from complex environmental matrices. | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) is widely used for sediment samples [21]. PCI (Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl) method is a traditional alternative for water filters [20]. |

| Universal PCR Primers | Amplifies target barcode regions from a wide range of taxa present in the eDNA sample. | Plants: trnL (UAA) intron P6 loop [19]. Vertebrates: mitochondrial 12S gene [19]. Microbes/General Eukaryotes: 16S rRNA (V3-V4), 18S rRNA [20]. |

| Blocking Oligonucleotides | Suppresses amplification of predator or non-target host DNA (e.g., in diet studies) to increase detection sensitivity for prey. | Designed to bind specifically to the non-target DNA template (e.g., fox or badger DNA in a diet study [19]). |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Generates millions of DNA sequences in parallel from a multiplexed library. | Illumina HiSeqX [21] or similar platforms (e.g., MiSeq, NovaSeq). |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | Processes raw sequence data: quality filtering, denoising, taxonomic assignment, and diversity analysis. | QIIME2 [21], OBITools [19], MOTU clustering at 97% similarity [16]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- DNA Extraction with Spike-in Addition:

- Add a known, consistent quantity of internal spike-in DNA to each sample lysis buffer before the extraction process begins.

- Proceed with DNA extraction using a validated kit or protocol (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit for sediments [21] or the PCI method for water [20]).

- Include extraction blank controls (reagents only, no sample) to control for kit contamination.

- PCR Amplification with Blocking Primers:

- Amplify the extracted DNA using marker-specific universal primers (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria, 12S for vertebrates) that have been tagged with unique molecular identifiers (MIDs) to track samples after multiplexing [19] [16].

- In studies involving predator diet analysis (e.g., from feces), include blocking oligonucleotides to minimize amplification of the predator's own DNA [19].

- Library Preparation and Normalization:

- Purify the PCR products and normalize the concentrations of the individual amplicon libraries.

- Pool the normalized libraries into a single, multiplexed sequencing library.

- High-Throughput Sequencing:

- Sequence the pooled library on an appropriate Illumina platform (e.g., HiSeqX [21]) to generate millions of paired-end reads.

- Bioinformatic Processing and Normalization:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to their original samples based on MID tags.

- Quality Control: Filter reads based on quality scores and merge paired-end reads.

- Denoising & Clustering: Cluster sequences into Molecular Operational Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) at a defined similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [21] or use denoising algorithms to generate Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify MOTUs/ASVs by comparing them to curated reference databases (e.g., GenBank, BOLD) [16].

- Spike-in Normalization: Calculate the recovery rate of the internal spike-in DNA in each sample. Use this to normalize the sequence counts of biological taxa, transforming raw read counts into relative abundance estimates that are comparable across samples.

Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow for quantitative eDNA metabarcoding, from field sampling to data interpretation.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for quantitative eDNA metabarcoding. This diagram outlines the key phases of the eDNA metabarcoding process, highlighting the critical point of internal spike-in DNA addition for quantitative normalization and the resulting applications.

Implementing Spike-In Controls: A Step-by-Step Guide from Sample to Sequence

The quantification of species abundance via environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding represents a revolutionary advancement in biomonitoring, yet its accuracy is fundamentally constrained by methodological biases. Spike-in controls serve as essential internal standards to correct for these technical variations, enabling reliable cross-sample comparisons and moving from relative to absolute quantification. These controls account for inefficiencies in DNA extraction, amplification biases, and stochastic variation during sequencing [5] [4]. The choice between model organisms and synthetic sequences as spike-ins depends on the specific research context, each offering distinct advantages for validating the eDNA metabarcoding workflow within quantitative research frameworks.

The critical need for standardization in molecular methods has been emphasized across scientific disciplines. As noted in insect metabarcoding studies, the field "lacks agreement on methodology or community standards," a challenge that spike-in controls can help mitigate [4]. Similarly, in clinical research, the noticeable "lack of technical standardization remains a huge obstacle" for quantitative PCR applications, highlighting the universal importance of robust internal controls [23]. This protocol provides a comprehensive guide for selecting, designing, and implementing both biological and synthetic spike-in controls to advance quantitative eDNA research.

Types of Spike-In Controls: Comparative Advantages and Applications

Spike-in controls are broadly categorized into three types, each with characteristic strengths and limitations suited to different experimental designs in quantitative eDNA metabarcoding.

Table 1: Comparison of Spike-In Control Types for Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding

| Control Type | Composition | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Spike-Ins | Intact organisms or cells added to samples | Controls for entire workflow including cell lysis; Uses actual DNA within cellular structures | Biological variability between individuals; Difficult to maintain consistent long-term supply; Requires careful species selection to avoid natural occurrence in samples | Evaluating DNA extraction efficiency from different cell wall types (e.g., gram-positive vs. gram-negative) [24] |

| DNA Spike-Ins | Extracted genomic DNA or amplicons added to samples | Controls for post-extraction steps; More precise quantification than biological spike-ins | Limited source material; Potential degradation during storage; Difficult to recreate if source is lost | Assessing PCR amplification efficiency and library preparation bias [4] |

| Synthetic Spike-Ins | Artificially designed DNA sequences synthesized in laboratory | Infinite future supply; Exactly defined sequences; No similarity to natural sequences; Highly reproducible | Does not control for cell lysis efficiency; Requires sophisticated in silico design | Absolute quantification in metabarcoding; Long-term monitoring studies requiring standardized controls across projects [25] [4] |

The selection of appropriate spike-in controls should be guided by the principle of "fit-for-purpose" validation, where "the level of validation associated with a medical product development tool is sufficient to support its context of use" [23]. For research aiming to evaluate complete DNA extraction efficiency from diverse microbial communities with varying cell wall structures, biological spike-ins using model organisms are particularly valuable. Conversely, for studies focusing on quantification of specific taxa in complex environmental samples, synthetic spike-ins offer superior standardization and long-term reproducibility.

Model Organisms as Biological Spike-In Controls

Selection of Model Organisms

The selection of appropriate model organisms for spike-in controls requires careful consideration of biological characteristics and experimental practicality. Ideal candidates should not occur naturally in the study environment, possess distinct genomic features enabling specific detection, and represent biological relevant characteristics such as different cell wall structures. A validated approach uses two single-gene deletion mutants from both Escherichia coli (gram-negative) and Bacillus subtilis (gram-positive) to simultaneously track different DNA states and bacterial origins [24].

This dual-organism approach enables researchers to address a critical methodological challenge: "Compared to gram-negative bacteria, gram-positive species possess a thicker cell wall, which is characterised by multiple crosslinked peptidoglycan layers, and therefore, they seem to be less accessible during DNA extraction" [24]. By including both types, researchers can quantify extraction efficiency biases across microbial taxa with different cellular structures.

Experimental Protocol: Implementation of Model Organism Spike-Ins

Materials Required:

- Single-gene deletion mutants of E. coli and B. subtilis with unique antibiotic resistance cassettes

- Appropriate culture media and antibiotics for selective growth

- Environmental samples (soil, sediment, water, etc.)

- DNA extraction kit suitable for the sample matrix

- Species-specific primers and probes for digital PCR

- Digital PCR system and reagents

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Culture and Preparation of Spike-In Cells

- Grow E. coli and B. subtilis mutant strains in appropriate media with selection antibiotics to mid-log phase.

- For intracellular DNA (iDNA) controls: Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with buffer to remove extracellular DNA. Resuspend in appropriate solution and quantify cell density using microscopy or flow cytometry.

- For extracellular DNA (exDNA) controls: Extract genomic DNA from a portion of the culture using a standard DNA extraction method. Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometry.

Spike-In Addition to Environmental Samples

- Add predetermined quantities of iDNA (as cells) and exDNA (as purified DNA) to environmental samples. The study by demonstrated successful application across "various environments including soil, sediment, sludge and compost" [24].

- The number of added spike-ins should be optimized: too low may be undetectable, while too high may interfere with native eDNA signals. Conduct pilot experiments to determine the optimal spiking level.

DNA Extraction and Purification

- Perform DNA extraction using your standard protocol. Note that "the choice of the DNA extraction method determines the reliability of obtained results" [24].

- Include non-spiked environmental samples as negative controls and extraction blanks to monitor contamination.

Absolute Quantification Using Digital PCR

- Perform multiplex digital PCR using unique primer/probe sets specific to each mutant strain. These should "target the terminal ends of the resistance cassette and adjacent flanking regions as these boundaries are unique to each strain" [24].

- Calculate percent recovery for each spike-in: (Measured concentration / Expected concentration) × 100.

Data Normalization and Analysis

- Use recovery efficiencies to correct quantitative measurements of native taxa in eDNA samples.

- Compare recovery between gram-positive and gram-negative spike-ins to identify potential extraction biases.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for implementing model organism spike-in controls in eDNA studies

Synthetic Spike-In Controls: Design and Implementation

Design Principles for Synthetic Spike-Ins

Synthetic spike-in controls are artificially designed DNA sequences that are synthesized in vitro and added to eDNA samples to enable precise quantification. Effective design follows several key principles:

Unique Sequence Composition: Synthetic spike-ins "are designed to lack similarity to any sequence in public databases" to prevent misidentification as biological taxa [4]. This is typically achieved by creating novel sequences or by scrambling natural sequences while maintaining similar nucleotide composition.

Length and GC-Content Considerations: The synthetic sequences should approximate the length and GC-content of target eDNA fragments to experience similar amplification efficiencies. For instance, in plant pathogen diagnostics, the single-copy TEF1 gene was selected because it "has relatively uniform G + C content and length" across target species [25].

Multi-Target Strategy: Including multiple synthetic spike-ins at different concentrations provides a standard curve for quantification. The qMiSeq approach "allows us to convert the sequence read numbers of detected taxa to DNA copy numbers based on a linear regression between known DNA copy numbers and observed sequence reads of internal standard DNAs" [5].

Experimental Protocol: Synthetic Spike-In Metabarcoding (SSIM)

Materials Required:

- Synthetic DNA sequences (designed in silico and commercially synthesized)

- eDNA samples from study environment

- Universal primers for target taxonomic group (e.g., MiFish-U for fish)

- High-throughput sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics pipeline for sequence processing

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Synthetic DNA Design and Preparation

- Design artificial DNA sequences that contain the primer binding sites used in your metabarcoding assay but have unique internal sequences.

- For quantitative applications, design a dilution series of synthetic standards covering expected eDNA concentrations. A study on Fusarium quantification demonstrated that SSIM "was both precise (R2 > 0.93 for three Fusarium species) and proportional (slope ~1) in relation to qMET" [25].

- Commercial synthesis of designed sequences, followed by cloning into plasmids or amplification to create working stocks.

Spike-In Addition and DNA Extraction

- Add known quantities of synthetic spike-ins to each eDNA sample prior to DNA extraction. For absolute quantification, add spike-ins "right before the DNA amplification step" [4].

- Proceed with standard DNA extraction protocol appropriate for your sample matrix.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Amplify target regions using universal primers. For fish communities, the MiFish-U primer set has been successfully used with the qMiSeq approach [5].

- Include appropriate controls for contamination and amplification artifacts.

- Sequence amplified libraries using high-throughput sequencing platforms.

Bioinformatic Processing and Quantification

- Demultiplex sequences and separate synthetic spike-ins from biological eDNA based on their unique sequences.

- For each sample, construct a standard curve by plotting the known copy numbers of synthetic spike-ins against their sequence read counts.

- Apply the sample-specific regression model to convert read counts of biological taxa to estimated DNA copy numbers.

Validation and Data Interpretation

- Validate the quantitative approach by comparing with independent methods. demonstrated "significant positive relationships between the eDNA concentrations of each species quantified by qMiSeq and both the abundance and biomass of each captured taxon" [5].

- Apply correction factors based on spike-in recovery to estimate absolute abundances of target taxa in original samples.

Figure 2: Workflow for implementing synthetic spike-in controls in eDNA metabarcoding studies

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Spike-In Implementation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Spike-In Controlled eDNA Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Single-gene deletion mutants of E. coli and B. subtilis [24] | Provide biological spike-ins representing different cell wall structures; Enable simultaneous tracking of iDNA and exDNA |

| Detection Reagents | Species-specific primers and probes for digital PCR [24] | Enable absolute quantification of spike-in controls without cross-reactivity with native communities |

| Universal Primers | MiFish-U for fish communities [5] | Amplify target DNA from multiple species while maintaining quantitative relationships; Essential for metabarcoding approaches |

| Synthetic Standards | Artificially designed DNA sequences [25] [4] | Provide precisely quantifiable internal standards that lack similarity to natural sequences; Enable absolute quantification |

| Quantification Platform | Digital PCR systems [24] | Provide absolute quantification without standard curves; Higher precision than qPCR for low-abundance targets |

| Sequencing Technology | High-throughput sequencers (e.g., Illumina iSeq) [5] | Enable simultaneous sequencing of multiple samples and spike-ins; Required for metabarcoding approaches |

The integration of appropriately designed spike-in controls represents a critical advancement in moving eDNA metabarcoding from qualitative presence-absence data toward robust quantitative applications. As emphasized in guidelines for molecular methods, "the incorporation of spike-ins into the metabarcoding workflow serves a dual purpose. Firstly, they act as sample-specific positive controls, enhancing the evaluation of data quality. Moreover, spike-ins play a pivotal role in decreasing variation that occurs during molecular processing and sequencing" [4].

The choice between model organisms and synthetic sequences depends on the specific research questions and constraints. Biological spike-ins using model organisms like E. coli and B. subtilis are invaluable for evaluating complete workflow efficiency including cell lysis, particularly when studying diverse microbial communities with varying cellular structures [24]. Conversely, synthetic spike-ins offer superior standardization, long-term reproducibility, and precise quantification for time-series studies and large-scale monitoring programs [25] [4].

As the field of eDNA research continues to mature, the implementation of spike-in controls will play an increasingly important role in standardizing methodologies across laboratories and studies. This standardization is essential for building comparable datasets that can effectively inform conservation decisions, ecosystem management, and our understanding of ecological dynamics in a rapidly changing world.

The efficacy of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding is fundamentally rooted in the initial sampling steps, where the choices of water volume and filter pore size directly determine the quantity and quality of DNA available for subsequent analysis. Within the broader context of quantitative eDNA metabarcoding research utilizing internal spike-in DNAs, optimizing these parameters is paramount for achieving accurate, reproducible, and quantitatively meaningful data. This protocol provides a structured framework for making informed decisions on water volume and filter pore size, grounded in empirical research, to maximize the detection probability and quantitative assessment of specific target taxa, particularly macroorganisms such as fish.

Key Principles and Experimental Findings

The optimization of sample collection is not a one-size-fits-all process; it requires a balance between maximizing target DNA recovery and managing practical constraints such as filtration time and inhibitor co-concentration. The table below summarizes core findings from recent investigations into these parameters.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on Water Volume and Filter Pore Size

| Study Focus | Key Finding | Implication for Protocol Design |

|---|---|---|

| Pore Size for Macroorganisms | Larger pore size filters (5 µm vs. 1 µm) maximize the ratio of amplifiable target DNA to total DNA for a marine mammal (bottlenose dolphin) without compromising absolute target detection [1]. | Larger pores selectively capture larger DNA particles (e.g., from metazoans), reducing the co-capture of abundant microbial DNA and effectively increasing the relative abundance of target DNA. |

| Water Volume | Larger volumes of water filtered (3 L vs. 1 L) maximize the ratio of target DNA to total DNA [1]. | Filtering larger volumes increases the absolute amount of target DNA collected, enhancing detection probability for rare taxa. |

| Total vs. Target DNA | Maximizing total DNA yield does not always increase target detection, as it can concentrate PCR inhibitors and off-target DNA [1]. | The goal should be to optimize the target-to-total DNA ratio, not simply to collect the most total DNA. |