Removal of Chironomus kiiensis Alters Rice Gene Expression: An Ecological Network Approach to Crop Biomarker Discovery

This article investigates the specific molecular and phenotypic responses of rice (Oryza sativa) to the removal of the midge Chironomus kiiensis, an organism identified as ecologically influential through nonlinear time...

Removal of Chironomus kiiensis Alters Rice Gene Expression: An Ecological Network Approach to Crop Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

This article investigates the specific molecular and phenotypic responses of rice (Oryza sativa) to the removal of the midge Chironomus kiiensis, an organism identified as ecologically influential through nonlinear time series analysis of intensive field monitoring data. We detail a methodological framework that integrates environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding for comprehensive ecological community assessment with transcriptome analysis to pinpoint crop responses to targeted biotic manipulations. Aimed at researchers and scientists in agro-biotechnology and drug development, this work validates a novel approach for detecting previously overlooked biological interactions in complex systems. The findings demonstrate a direct link between a specific macrobial species and rice gene expression patterns, offering a proof-of-concept for harnessing ecological complexity to identify novel biomarkers and pathways relevant to both sustainable agriculture and the understanding of biological stress responses.

Chironomus kiiensis as a Keystone Species: Uncovering Its Ecological Role in Rice Agroecosystems

While abiotic factors like drought, salinity, and temperature extremes have dominated crop stress research, the complex influence of ecological community members on crop performance remains a significant knowledge gap in agricultural science. Rice (Oryza sativa L.), a staple food for over 3.5 billion people, is typically grown in field conditions where it is inevitably influenced by surrounding biotic variables including microbes, insects, and other ecological community members [1] [2]. Understanding these interspecific interactions has been underexplored despite its critical importance for sustainable agriculture [1]. This review examines pioneering methodologies detecting influential organisms in rice agroecosystems, with particular focus on the effects of Chironomus kiiensis manipulation on rice growth and gene expression.

Experimental Approaches for Detecting Biotic Influences

Ecological Network Analysis and Field Validation

A groundbreaking 2017-2019 study demonstrated an ecological-network-based approach to identify previously overlooked organisms influencing rice performance [1] [2]. The research employed intensive daily monitoring of experimental rice plots over 122 consecutive days, combining quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis [2]. This methodology detected more than 1,000 species in the rice plots and identified 52 potentially influential organisms [1].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters from Ecological Network Study

| Parameter | 2017 Monitoring Phase | 2019 Validation Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 122 days (May-Sept) | Not specified |

| Rice Plots | 5 experimental plots | Artificial manipulation plots |

| Monitoring Frequency | Daily | Pre/post manipulation |

| Species Detected | >1,000 | Focus on 2 target species |

| Analysis Method | Nonlinear time series analysis | Field manipulation |

| Rice Metrics | Growth rate (cm/day) | Growth rate + gene expression |

In 2019, the research team empirically validated the time series analysis by manipulating two species identified as potentially influential: the Oomycete Globisporangium nunn (syn. Pythium nunn) and the midge Chironomus kiiensis [1] [2]. The team added G. nunn and removed C. kiiensis from small rice plots, then measured rice growth rates and gene expression patterns before and after manipulation [3]. The confirmation that these species, particularly G. nunn, statistically affected rice performance demonstrated the potential of integrating eDNA monitoring with time series analysis to detect influential organisms in agricultural systems [1].

Molecular Approaches to Stress Response

Complementary research has employed modular gene co-expression analysis to identify hub genes associated with biotic and abiotic stress responses in rice [4]. This approach analyzed microarray datasets for drought, salinity, tungro virus, and blast pathogen stress, identifying multiple gene modules and hub genes implicated in stress responses [4]. The protein-protein interaction network constructed from these analyses revealed several consistently present genes across abiotic and biotic stresses, including RPS5, PKG, HSP90, HSP70, and MCM [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Biotic Influence Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding | Comprehensive species detection in environmental samples | 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI primer sets [2] |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis | Reconstruction of ecological interaction networks | Detection of causal relationships from time series data [1] |

| Modular Gene Co-expression Analysis (mGCE) | Identification of stress-responsive hub genes | CEMiTool analysis of microarray datasets [4] |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Gene silencing in non-model organisms | dsRNA targeting CYP6EV11 in C. kiiensis [5] |

| qRT-PCR | Gene expression quantification | Relative expression of heat shock proteins [6] |

| Aloinoside A | Aloinoside A, CAS:56645-88-6, MF:C27H32O13, MW:564.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Octocrylene-d10 | Octocrylene-d10, MF:C24H27NO2, MW:371.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow for Ecological Network Analysis

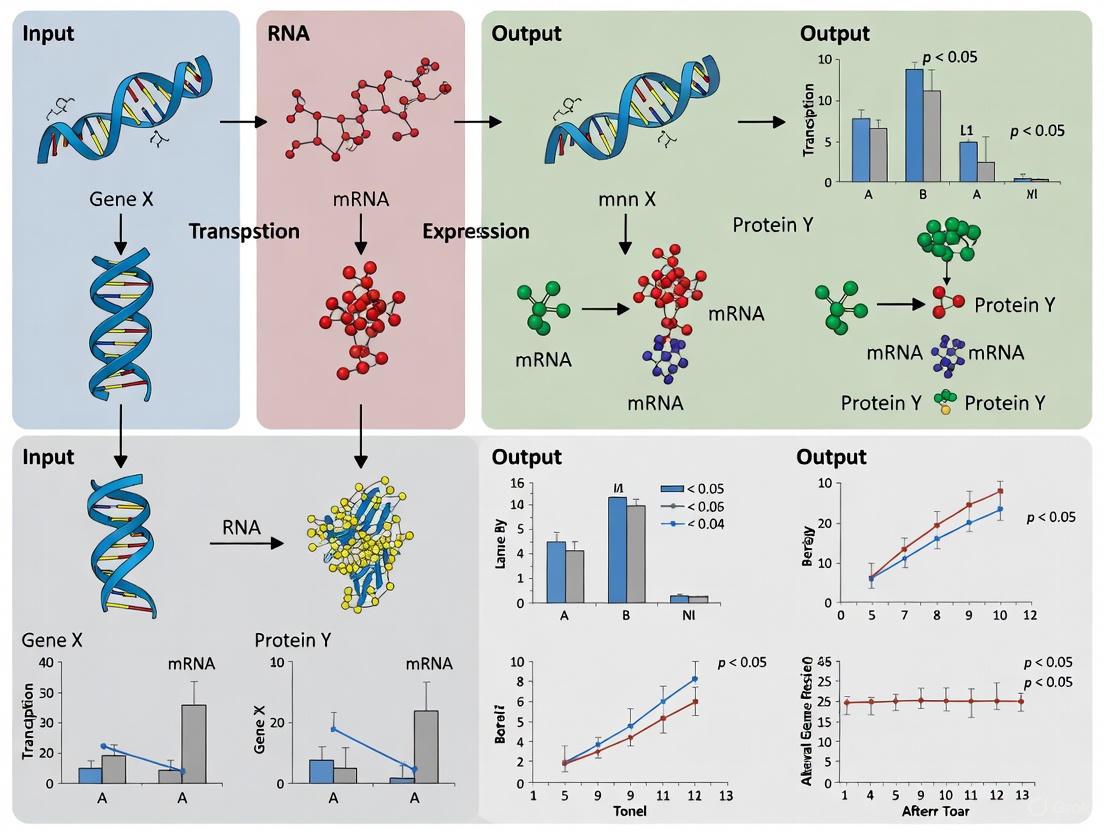

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for detecting and validating influential organisms in rice agroecosystems:

Signaling Pathways in Rice Stress Response

The molecular mechanisms underlying rice responses to biotic stresses involve complex signaling pathways and transcriptional reprogramming:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Environmental DNA Metabarcoding Protocol

The ecological network study employed comprehensive eDNA metabarcoding with four universal primer sets targeting different taxonomic groups [2]:

- Sample Collection: Approximately 200ml of water was collected daily from each rice plot and filtered using 0.22-µm and 0.45-µm Sterivex filter cartridges [7]

- DNA Extraction: eDNA was extracted from filters and purified, with internal spike-in DNAs added for quantitative analysis [2]

- Amplification and Sequencing: Four primer sets amplified 16S rRNA (prokaryotes), 18S rRNA (eukaryotes), ITS (fungi), and COI (animals) regions [2]

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence data processed to identify operational taxonomic units and quantify species abundance [1]

Field Manipulation Experiment Protocol

The validation phase in 2019 employed rigorous field manipulation methods [1]:

- Plot Establishment: Artificial rice plots created using standardized containers with commercial soil and rice seedlings (var. Hinohikari)

- Species Manipulation: G. nunn was added to plots while C. kiiensis was removed from treatment plots

- Response Measurement: Rice growth rates were measured by leaf height tracking, and gene expression patterns were analyzed through transcriptome profiling

- Control Conditions: Appropriate control plots maintained for comparison

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Table 3: Comparison of Approaches for Studying Biotic Influences on Crops

| Methodological Aspect | Ecological Network Approach | Gene Co-expression Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Species interactions in field conditions | Molecular networks and hub genes |

| Data Type | Time series abundance data | Gene expression microarray/RNA-seq |

| Scale of Analysis | Whole ecological community | Transcriptional regulatory networks |

| Key Output | Influential species identification | Stress-responsive hub genes |

| Validation Approach | Field manipulation experiments | qRT-PCR of candidate genes |

| Temporal Resolution | Daily monitoring over growing season | Specific stress time points |

| Throughput | 1,000+ species simultaneously | 10s-100s of gene modules |

The integration of ecological network analysis with molecular genetics approaches represents a promising frontier for addressing the critical knowledge gap in underexplored biotic influences on crop performance. The validation of Chironomus kiiensis and Globisporangium nunn as influential organisms demonstrates that previously overlooked species can significantly impact rice growth and gene expression [1]. Future research should leverage these complementary approaches to harness ecological complexity for sustainable agriculture, potentially leading to novel strategies for crop improvement that consider the entire ecological community rather than focusing solely on traditional breeding targets.

Ecological network theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the complex web of interactions that sustain ecosystems. The concept of keystone species—organisms with disproportionately large effects on their environment relative to their abundance—has been fundamental to both theoretical and applied ecology since Robert Paine's pioneering research on predatory sea stars in the 1960s [8]. When keystone species are removed from ecosystems, they can trigger trophic cascades that dramatically alter ecosystem structure and function, as demonstrated by the wolf reintroduction program in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem which restored balance to plant communities and even changed the physical geography of rivers [8].

Modern agricultural science now stands to benefit tremendously from these ecological insights. Rather than viewing farms as simplified production systems, researchers are increasingly recognizing that agricultural management can harness ecological interactions to improve sustainability and productivity [9]. This paradigm shift acknowledges that crops like rice are grown in complex field environments where they are influenced by countless surrounding organisms, from microbes to insects [1] [10]. Understanding these interactions through the lens of ecological network theory opens new possibilities for sustainable agriculture that works with, rather than against, natural processes.

Keystone Species Identification: From Traditional to Modern Approaches

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Methods

The identification of keystone species has evolved significantly from early observational approaches. Traditional ecology relied heavily on manipulation experiments where researchers would remove specific species and observe the ecosystem consequences [8]. Paine's classic experiment involved physically removing Pisaster ochraceus sea stars from tidal plains and documenting how mussels subsequently dominated the area, crowding out other species and reducing overall biodiversity [8]. Similarly, the unintended removal of wolves from Yellowstone provided a natural experiment demonstrating how the loss of an apex predator allows herbivore populations to explode, leading to overgrazing that affects multiple trophic levels [8].

These traditional approaches revealed that keystone species have low functional redundancy, meaning no other species can fill their ecological role if they disappear [8]. However, observation- and manipulation-based approaches have critical limitations: they are labor-intensive, difficult to scale, and may miss subtle but important interactions in complex systems [1] [10].

Advanced Network-Based Identification Methods

Contemporary ecology has developed sophisticated network analysis approaches to identify keystone species more systematically. One promising method uses motif centrality, which identifies keystone species based on their participation in specific subnetwork patterns (motifs) within larger food webs [11]. Research shows that species with high motif-based centrality—those that participate frequently in key interaction patterns—cause significantly more secondary extinctions when removed than would be expected by chance [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Keystone Species Identification Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Removal Experiments [8] | Physical removal of species with observation of ecosystem effects | Direct evidence of ecological impact; Clear demonstration of causality | Labor-intensive; Difficult to scale; Limited to observable effects |

| Motif Centrality [11] | Analysis of species' participation in key subnetwork patterns | Systematic identification; Captures indirect interactions; Applicable to complex webs | Requires detailed interaction data; Computationally intensive |

| Network Robustness Analysis [11] | Simulation of secondary extinctions after species removal | Predictive power; Quantifiable impact measurement; Identifies vulnerable species | Dependent on model accuracy; May oversimplify interactions |

| eDNA Monitoring + Nonlinear Time Series [1] [10] | Causality detection from frequent community monitoring | Comprehensive species detection; Reveals hidden interactions; Minimal ecosystem disturbance | Requires specialized expertise; Validation still needed |

Another network-based approach analyzes how species removals affect food web robustness. In both topological models (which treat species as fixed nodes) and dynamic models (which simulate population dynamics), researchers can quantify how the removal of different species affects the likelihood of secondary extinctions throughout the network [11]. These methods have revealed that certain species play disproportionately important roles in maintaining the structural integrity of ecological networks.

Ecological Networks in Agricultural Systems: A Case Study in Rice Management

An Integrated Framework for Detecting Influential Organisms

A groundbreaking study demonstrated how ecological network theory could be applied to identify influential organisms in rice agroecosystems [1] [10]. The research employed an integrated approach combining advanced monitoring technologies with nonlinear time series analysis to map species interactions and their effects on rice growth.

The methodology involved three key phases conducted over multiple years. In 2017, researchers established small experimental rice plots and implemented intensive monitoring of both rice growth and ecological communities [1] [10]. This was followed by network analysis to identify potentially influential organisms, and finally field validation in 2019 to test the predictions through manipulative experiments [1] [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Field Monitoring and Environmental DNA Analysis

The research team established five artificial rice plots using small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm) in an experimental field at Kyoto University, Japan [7]. Each plot contained sixteen Wagner pots filled with commercial soil, with three rice seedlings (variety Hinohikari) planted in each pot [7]. The monitoring protocol included:

- Daily rice growth measurements: Researchers measured rice leaf height of target individuals every day using a ruler, focusing on the largest leaf heights [7].

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling: Approximately 200 ml of water was collected daily from each rice plot and filtered using two types of Sterivex filter cartridges (φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm) [7].

- Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding: eDNA was extracted from filters and sequenced using internal spike-in DNAs to enable quantitative assessment of species abundances [1] [10].

- Climate monitoring: Temperature, light intensity, and humidity were monitored at each rice plot throughout the experiment [7].

This comprehensive monitoring approach detected more than 1,000 species in the rice plots, including microbes, insects, and other organisms [1] [10]. The daily sampling continued for 122 consecutive days, generating an extensive time series of ecological community dynamics alongside rice growth metrics.

Nonlinear Time Series Analysis and Causality Detection

The research team applied nonlinear time series analysis to the extensive dataset to detect causal relationships between species abundances and rice growth [1] [10]. This analytical approach can identify potential interactions even in complex, nonlinear systems where traditional correlation methods might fail.

The analysis identified 52 potentially influential organisms with statistically significant effects on rice growth rates [1] [10]. From these candidates, two species were selected for further experimental validation: the oomycete Globisporangium nunn (syn. Pythium nunn) and the midge Chironomus kiiensis [1] [10].

Diagram Title: Ecological Network Analysis Workflow for Rice Management

Effects of Chironomus kiiensis Manipulation on Rice Gene Expression

Experimental Validation of Network Predictions

In 2019, researchers conducted field manipulation experiments to test the predictions generated by the ecological network analysis [1] [10]. The experiments focused on two species identified as potentially influential: Globisporangium nunn (an oomycete) and Chironomus kiiensis (a midge species) [1] [10].

The experimental design involved:

- G. nunn-added treatment: Artificial introduction of the oomycete to rice plots

- C. kiiensis removal treatment: Selective removal of the midge species from rice plots

- Control conditions: Unmanipulated plots for comparison

- Response measurements: Rice growth rates and gene expression patterns measured before and after manipulation [1] [10]

The results provided validation for the network-based predictions, showing that G. nunn addition, in particular, produced statistically significant changes in rice growth rates and gene expression patterns [1] [10]. While the effects of C. kiiensis manipulation were present but relatively small, the study demonstrated the potential of this approach to identify previously overlooked organisms that influence crop performance [1] [10].

Molecular Responses of Chironomus kiiensis to Environmental Stressors

Complementary research on Chironomus kiiensis has revealed sophisticated molecular response mechanisms to environmental stressors, which may help explain its influence in agricultural ecosystems. Transcriptome profiling of C. kiinensis under phenol stress identified 10,724 differentially expressed genes (6,032 unigenes classified by Gene Ontology, 18,366 unigenes categorized into 238 KEGG pathways) [12]. Key response pathways included:

- Metabolic pathways

- Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling

- Pancreatic secretion pathways

- Neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions [12]

Further research has examined the endocrine-disrupting effects of neonicotinoid insecticides on Chironomus kiinensis, revealing that chronic exposure to dinotefuran:

- Delayed pupation and emergence via inhibition of ecdysis

- Shifted sex ratios toward male-dominated populations

- Significantly downregulated ecdysis-related gene expressions (ecr, usp, E74, and hsp70)

- Upregulated vitellogenin (vtg) gene expression, indicating estrogenic effects [13]

Additional molecular studies have identified that UDP-glucuronosyltransferase is involved in the susceptibility of Chironomus kiiensis to insecticides, providing insights into detoxification mechanisms [14].

Table 2: Molecular Response Mechanisms of Chironomus kiiensis to Environmental Stressors

| Stress Type | Key Molecular Findings | Gene Expression Changes | Physiological Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol Stress [12] | 10,724 differentially expressed genes; Activation of AhR pathway | 8,390 upregulated; 2,334 downregulated genes | Metabolic adaptation; Detoxification response |

| Neonicotinoid Exposure [13] | Disruption of ecdysone pathway; Estrogenic effects | Downregulation of ecr, usp, E74, hsp70; Upregulation of vtg | Delayed development; Male-biased sex ratios |

| Insecticide Exposure [14] | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase involvement in detoxification | Enzyme activity modification | Altered susceptibility to insecticides |

Diagram Title: Chironomus kiiensis Molecular Response Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Ecological Network Studies in Agriculture

| Reagent/Method | Specific Application | Key Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding [1] [10] | Comprehensive species detection in rice plots | Amplification and sequencing of DNAs from environmental samples with internal spike-ins for quantification | Monitoring of 1,000+ species in rice plots; Daily sampling over 122 days |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis [1] [10] | Detection of causal relationships in species interactions | Reconstruction of complex interaction networks from time series data | Identification of 52 potentially influential organisms from 1,197 species |

| Solexa Sequencing Technology [12] | Transcriptome profiling under stress conditions | High-throughput sequencing for gene expression analysis | Identification of 10,724 differentially expressed genes in C. kiinensis under phenol stress |

| HPLC-MS/MS Analysis [13] | Quantification of insecticide concentrations | Precise chemical analysis using mass spectrometry | Measurement of dinotefuran actual concentrations in exposure samples |

| ATP Assay Kit [13] | Measurement of cellular energy levels | Colorimetric detection of adenosine triphosphate | Assessment of metabolic effects in C. kiinensis after neonicotinoid exposure |

| RNAi Technology [14] | Gene function analysis | Targeted gene silencing using RNA interference | Investigation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase role in insecticide susceptibility |

| Bet-IN-15 | Bet-IN-15 | Bet-IN-15 is a potent BET bromodomain inhibitor. This product is for research use only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Ent-(+)-Verticilide | Ent-(+)-Verticilide, MF:C44H76N4O12, MW:853.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Analysis of Agricultural Management Approaches

Traditional vs. Ecology-Informed Management Strategies

The application of ecological network theory to agriculture represents a significant shift from conventional approaches. Traditional agricultural management often focuses on single-species interventions, such as pesticide applications or fertilizer amendments, with limited consideration of the broader ecological context [9]. In contrast, ecology-informed approaches recognize that crop performance emerges from complex interactions among multiple species within agricultural ecosystems [1] [10].

Network analyses of invertebrate communities across 502 UK farm sites revealed that GMHT management (genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops) did not significantly alter network-level properties or robustness, despite taxon-specific effects [15]. This suggests that ecological networks may demonstrate resilience to certain agricultural disturbances, and that autecological assessments (focusing on single species) may overlook compensatory effects within the wider ecosystem [15].

Towards Sustainable Agricultural Management

The integration of ecological network theory into agricultural practice offers promising pathways for sustainable intensification of food production. By identifying key species that influence crop performance, researchers and farmers can develop targeted management strategies that harness natural processes rather than overriding them [1] [9].

This approach aligns with the concept of "ecological intensification" which relies on services provided by ecological networks to maintain productivity while reducing environmental impacts [9]. The research framework demonstrated in the rice study—combining intensive monitoring, network analysis, and experimental validation—provides a template for identifying management opportunities across different agricultural systems [1] [10].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on eco-evolutionary dynamics, considering how agricultural practices select for specific traits in both crops and associated organisms, and how these evolutionary changes feedback to affect ecosystem functioning and services [9]. Understanding these dynamics will be crucial for designing agricultural systems that are both productive and sustainable in the face of environmental change.

Biological and Ecological Profile ofChironomus kiiensis

Chironomus kiiensis is a species of non-biting midge (family Chironomidae) that inhabits rice paddy ecosystems. As with other chironomids, it is an aquatic insect whose larval stages develop in the benthic (bottom-dwelling) environments of flooded rice fields [16]. These organisms play a significant role in the agricultural ecosystem, serving as an alternative food source for predatory natural enemies of rice insect pests, especially during periods when pest populations are low [17].

The larvae of Chironomus kiiensis are typically found in the sediments and aquatic environments of rice paddies [2]. They possess the characteristic features of chironomid larvae, including an elongate, cylindrical body with distinct segmentation and a hardened head capsule [16]. While many chironomid larvae are tan or brown, some species appear whitish or green, and those containing hemoglobin (often called "bloodworms") may exhibit a pinkish or red coloration [16].

Life Cycle and Development Parameters

Like all members of the Chironomidae family, Chironomus kiiensis undergoes complete metamorphosis (holometabolism), progressing through four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult [16]. The life cycle characteristics of a closely related species, Chironomus sp. "Florida", provide insights into the general developmental patterns that may be expected for C. kiiensis under tropical and subtropical conditions [18].

Table 1: Life Cycle Characteristics of Chironomus Species Under Laboratory Conditions

| Life Stage | Duration/Dimensions | Environmental Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Egg | Laid in gelatinous masses on water surface [16] | Gravid females attracted to polarized light from water surfaces [18] |

| Larva | 4 instar stages; duration varies with temperature and food availability [18] | Warm temperatures (≈27°C) accelerate development [18] |

| Pupa | Transitional stage before adult emergence [16] | Pupae swim to water surface for adult emergence [16] |

| Adult | Small, slender flies 1-10 mm long; resemble mosquitoes but do not bite [16] | Short-lived (few days to weeks); form mating swarms [16] |

Table 2: Factors Influencing Chironomid Development

| Factor | Effect on Development |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Faster development at warmer temperatures (e.g., 11-day cycle at 27°C vs. longer at cooler temperatures) [18] |

| Food Availability | Food concentration effects interact with water volume; 2 mg/larva/day optimal in large water volumes [18] |

| Habitat Type | Larvae primarily benthic after first instar; build tubes in sediment for refuge [16] |

Experimental Evidence: Removal Studies and Rice Growth Response

Recent ecological network research has identified Chironomus kiiensis as a potentially influential organism in rice paddy ecosystems. A 2019 field manipulation experiment tested the effect of C. kiiensis removal on rice growth and gene expression patterns [1] [2].

Experimental Workflow for C. kiiensis Removal Study

This experiment was designed within the context of a broader research thesis investigating how ecological community members influence rice performance under field conditions [2]. The manipulation demonstrated that targeted removal of specific species like C. kiiensis can produce measurable changes in rice physiological responses, although the effects were relatively small compared to other manipulated organisms like Globisporangium nunn [2].

Toxicological Sensitivity and Ecological Risk Assessment

Chironomus kiiensis serves as a valuable bioindicator species for assessing ecological risks in rice ecosystems. Laboratory toxicity tests have quantified its response to pesticide exposure, particularly to chlorantraniliprole, a widely used insecticide in rice production [17].

Table 3: Toxicological Responses of C. kiiensis to Chlorantraniliprole

| Parameter | Exposure Concentration | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Lethal Toxicity (LC50) | Not specified in available data | Less sensitive than C. javanus [17] |

| Sublethal Effects | LC10 (1.50 mg/L) & LC25 (3.00 mg/L) | Prolonged larval development, inhibited pupation and emergence [17] |

| Detoxification Enzymes | Sublethal concentrations | Significant decrease in carboxylesterase (CarE) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) activity [17] |

| Antioxidant System | Sublethal concentrations | Marked inhibition of peroxidase (POD) activity [17] |

| Gene Expression | Sublethal concentrations | Significant changes in 7 genes related to detoxification and antioxidant functions [17] |

Table 4: Molecular Responses to Pesticide Exposure

| Gene/Enzyme Category | Specific Targets Affected | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Detoxification Genes | CarE6, CYP9AU1, CYP6FV2 | Impaired ability to metabolize environmental contaminants [17] |

| GST Genes | GSTo1, GSTs1, GSTd2 | Reduced capacity for cellular detoxification processes [17] |

| Antioxidant Genes | POD | Compromised oxidative stress response [17] |

These sublethal effects demonstrate that pesticide exposure can significantly impact C. kiiensis populations even at concentrations that do not cause immediate mortality, with potential implications for their ecological role in rice ecosystems.

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 5: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying C. kiiensis

| Reagent/Material | Application in Research | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) | Ecological monitoring | Quantitative metabarcoding to detect species presence and abundance [1] [2] |

| Universal Primer Sets | Species identification | Amplification of 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI gene regions [2] |

| Chlorantraniliprole | Toxicological testing | Insecticide exposure studies to determine lethal and sublethal effects [17] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Biochemical analysis | Quantifying activity of CarE, GSTs, POD, and CAT [17] |

| qPCR Reagents | Gene expression analysis | Measuring transcript levels of detoxification and antioxidant genes [17] |

| Culture Aquarium Systems | Laboratory rearing | Maintaining life cycle under controlled conditions (temperature, aeration, photoperiod) [18] |

The integration of these research approaches—from field monitoring and manipulation to molecular analysis—provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the ecological role of Chironomus kiiensis in rice paddies and its potential influence on rice growth and gene expression patterns.

The pursuit of sustainable agricultural productivity requires a deep understanding of the complex ecological networks within crop systems. While the influence of abiotic factors on crop growth is well-documented, the impact of surrounding ecological communities—encompassing countless microorganisms, insects, and other organisms—has remained largely unexplored due to methodological limitations [7] [2]. Rice (Oryza sativa), a staple food for over 3.5 billion people, is typically grown in field conditions where it interacts with diverse ecological communities, yet how these biotic interactions influence rice performance has been underexplored despite its importance for sustainable agriculture [1].

This methodological guide examines the groundbreaking 2017 field study that established an ecological network approach for detecting organisms influential to rice growth. The study pioneered the integration of quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis to reconstruct interaction networks surrounding rice plants under field conditions [7] [2]. By intensively monitoring over 1,000 species simultaneously, the research provided a novel framework for identifying previously overlooked species that significantly impact rice growth, culminating in the identification of 52 potentially influential organisms [10].

Experimental Design and Setup

Field Plot Configuration

The 2017 monitoring study established a controlled yet realistic field environment at the Center for Ecological Research, Kyoto University, in Otsu, Japan (34°58′18′′N, 135°57′33′′E) [7]. The experimental design prioritized both ecological relevance and methodological precision through the following implementation:

- Plot Structure: Five identical artificial rice plots were created using small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm; 216 L total volume) [7]

- Pot Configuration: Each container held sixteen Wagner pots filled with commercial soil [7]

- Planting Protocol: Three rice seedlings (var. Hinohikari) were planted in each pot on 23 May 2017 [7]

- Study Duration: Continuous monitoring from 23 May 2017 to 22 September 2017 (122 consecutive days) [7]

Rice Growth Monitoring

The study employed rigorous quantitative methods to track rice performance throughout the growing season:

- Measurement Protocol: Daily rice growth monitoring through measurement of rice leaf height of target individuals using a ruler [7]

- Growth Metric: Growth rates calculated as cm/day in height, selected because frequent and inexpensive monitoring is possible, and because it integrates various physiological states [2]

- Data Consistency: Growth patterns showed consistent patterns among the five plots, validating the experimental approach [2]

- Supplementary Metrics: Leaf SPAD values were also measured though not included in the final analysis [7]

Ecological Community Monitoring Protocol

Water Sampling Methodology

The comprehensive ecological monitoring followed a systematic sampling protocol:

- Sampling Frequency: Daily water sample collection from all five rice plots [7]

- Sample Volume: Approximately 200 ml of water collected from each plot [7]

- Processing Time: Samples transported to laboratory within 30 minutes of collection [7]

- Filtration Protocol: Water filtered using two types of Sterivex filter cartridges (φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm) [7]

- Total Samples: 1220 water samples collected (122 days × 2 filter types × 5 plots) plus negative controls [7]

eDNA Metabarcoding Analysis

The study employed cutting-edge molecular techniques for community analysis:

- Genetic Target Regions: Four universal primer sets targeting 16S rRNA (prokaryotes), 18S rRNA (eukaryotes), ITS (fungi), and COI (animals) regions [2]

- Quantitative Approach: Used internal spike-in DNAs to enable quantitative eDNA analysis, providing more informative community data than presence-absence metrics [7]

- Amplification and Sequencing: eDNA extracted from filters, purified, and analyzed via metabarcoding approaches [7]

Table 1: Primer Sets and Target Genetic Regions for eDNA Metabarcoding

| Target Group | Genetic Region | Primer Purpose | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotes | 16S rRNA | Universal amplification | Comprehensive bacterial and archaeal diversity |

| Eukaryotes | 18S rRNA | Universal amplification | Broad eukaryotic coverage including protists |

| Fungi | ITS | Taxon-specific amplification | Fungal-specific identification |

| Animals | COI | Taxon-specific amplification | Animal and insect identification |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Metabarcoding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterivex Filter Cartridges | φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm | eDNA Filtration | Particulate capture from water samples |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Commercial system | eDNA Extraction | Isolation of DNA from filters |

| PCR Reagents | Custom mixtures | Amplification | Target gene region amplification |

| Spike-in DNAs | Synthetic standards | Quantification | Internal standards for quantitative analysis |

| Sequencing Reagents | Platform-specific | Library Preparation | High-throughput sequencing |

| Negative Controls | Sterile water | Contamination Check | Process contamination monitoring |

| Coumarin-C2-exo-BCN | Coumarin-C2-exo-BCN, MF:C27H33N3O5, MW:479.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nitroso diisobutylamine-d4 | Nitroso diisobutylamine-d4, MF:C8H18N2O, MW:162.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Data Analysis Framework

Time Series Causality Analysis

The study employed advanced statistical approaches to derive ecological insights:

- Analytical Method: Nonlinear time series analysis based on quantitative eDNA time series [2]

- Causality Detection: Application of unified information-theoretic causality analysis to detect potential influences on rice growth [10]

- Network Reconstruction: Reconstruction of complex interaction networks from time series data [2]

- Species Identification: Detection of 52 potentially influential organisms with lower-level taxonomic information from initial 1,197 species monitored [10]

Key Findings from 2017 Monitoring

The intensive monitoring yielded several significant ecological patterns:

- Temporal Dynamics: Total eDNA copy number increased later in the sampling period, while ASV diversity (a surrogate of species diversity) peaked in August then decreased in September [2]

- Community Composition: Prokaryotes largely accounted for the observed patterns of total eDNA concentration [2]

- Growth Patterns: Daily rice growth rate reached maximum during late June to early July, with rice height ceasing to increase after mid-August [2]

- Network Complexity: Reconstruction of a large ecological interaction network revealed complex species interrelationships [2]

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow of the 2017 field study showing the integration of empirical data collection and computational analysis.

Validation and Follow-up Studies

2019 Field Manipulation Experiments

The 2017 findings were empirically validated through focused manipulative experiments in 2019:

- Candidate Selection: Two species identified as potentially influential in 2017 were selected for manipulation [1]

- Experimental Design: Addition of Globisporangium nunn (Oomycetes) and removal of Chironomus kiiensis (midge) from artificial rice plots [10]

- Response Metrics: Measurement of rice growth rates and gene expression patterns before and after manipulation [1]

- Key Finding: Confirmed statistically clear effects on rice performance, especially in the G. nunn-added treatment [7]

Methodological Validation

The reliability of eDNA approaches depends on several critical validation parameters as defined in contemporary methodological research [19]:

- Specificity: Correct amplification of targeted species without positive results from closely related species [19]

- Detection Probability: Probability that analysis of a replicate containing target DNA yields positive detection [19]

- Sensitivity/LOD: The lowest quantity of target DNA that can be reliably detected [19]

- Repeatability: The spread (r²) of data around regression lines used to standardize quantification [19]

- Accuracy: Variability of measurements contributing to a data point, including both natural and technical replicates [19]

Table 3: Comparative Performance of eDNA Detection Metrics from Validation Studies

| Validation Metric | High Reliability Profile | Moderate Reliability Profile | Critical Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Amplifies only target species | Cross-reactivity with related taxa | Primer design, probe selection |

| Detection Probability | >95% at target concentrations | 50-80% at target concentrations | DNA concentration, inhibition |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | Consistently detects low DNA quantities | Variable detection at low quantities | Assay efficiency, sample processing |

| Repeatability (r²) | >0.98 for standard curves | 0.85-0.95 for standard curves | Technical precision, replication |

| Accuracy (CV) | <5% coefficient of variation | 10-25% coefficient of variation | Replicate number, sampling design |

Integrated Research Framework

Diagram 2: Integrated research framework showing the progression from initial monitoring to validated findings.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

The 2017 study acknowledged several methodological considerations essential for proper interpretation of results:

- Manipulation Effects: While statistically clear, the effects of species manipulations were relatively small, suggesting complex ecological interactions rather than simple causal relationships [7]

- Primer Selection: The effectiveness of eDNA metabarcoding heavily depends on appropriate primer selection, as different primer sets can yield varying detection efficiencies [20]

- Quantitative Challenges: Accurate quantification requires internal standards and careful control for amplification biases [19]

- Temporal Dynamics: Ecological interactions vary across seasons and rice growth stages, necessitating intensive temporal sampling [2]

The 2017 field study established a groundbreaking methodological framework for understanding complex agricultural ecosystems. By integrating quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis, the research demonstrated that intensive monitoring of agricultural systems can identify previously overlooked organisms that influence crop performance [1].

This approach provides valuable insights for the broader research on effects of Chironomus kiiensis removal on rice gene expression by contextualizing specific species manipulations within comprehensive ecological networks. The methodology offers a powerful tool for identifying key organisms in agricultural systems, potentially leading to new environment-friendly agricultural management strategies that harness ecological complexity rather than attempting to simplify it [7] [10].

The research framework presents significant potential for future applications in sustainable agriculture, ecological research, and system-based crop management, moving beyond traditional single-factor approaches to embrace the complexity of agricultural ecosystems [1].

In agricultural science, a major challenge is to enhance sustainable food production while minimizing environmental impacts [1] [2]. Rice, as a staple crop for over 3.5 billion people, plays a crucial role in global food security, yet its performance under field conditions is influenced by a complex network of surrounding ecological community members [1] [2]. While advanced breeding techniques offer promising avenues for improvement, the intricate biotic interactions within rice ecosystems remain underexplored despite their potential for establishing environmentally friendly agricultural systems [1].

This article frames its analysis within a broader thesis investigating the effects of Chironomus kiiensis removal on rice gene expression, presenting a comparative examination of experimental approaches for detecting causal organisms influencing rice growth. We focus particularly on an ecological-network-based methodology that identified 52 potentially influential organisms through intensive field monitoring and nonlinear time series analysis [1] [2]. This research provides a framework for moving beyond correlation to establish causality in complex agricultural ecosystems, with particular relevance for understanding how specific manipulations like C. kiiensis removal trigger molecular responses in rice plants.

Experimental Approaches: Methodological Comparison

Ecological Network-Based Detection Protocol

The foundational methodology for organism detection employed a comprehensive ecological network approach, implemented through a multi-phase experimental design [1] [2]:

Phase 1: Intensive Field Monitoring (2017)

- Established five experimental rice plots at Kyoto University, Japan

- Conducted daily monitoring from May 23 to September 22, 2017 (122 consecutive days)

- Measured rice growth rates (cm/day in height) through daily physical measurements of target individuals

- Monitored ecological communities using quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding with four universal primer sets (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI regions targeting prokaryotes, eukaryotes, fungi, and animals respectively)

- Collected and analyzed water samples from all five plots daily

Phase 2: Causality Analysis

- Analyzed time series containing 1,197 species and rice growth rates

- Applied nonlinear time series analysis to reconstruct interaction networks surrounding rice

- Identified 52 potentially influential organisms with lower-level taxonomic information

- Utilized quantitative eDNA time series suitable for causality analysis requirements

Phase 3: Empirical Validation (2019)

- Conducted manipulative experiments focusing on two species identified in 2017

- Manipulated abundance of Globisporangium nunn (Oomycetes) through addition

- Manipulated abundance of Chironomus kiiensis (midge species) through removal

- Measured rice responses through growth rates and gene expression patterns before and after manipulation

- Employed statistical analysis to confirm effects on rice performance

Gene Expression Analysis Protocol

The investigation of Chironomus kiiensis removal effects on rice gene expression employed transcriptomic approaches [1]:

Sample Collection

- Collected rice tissue samples before and after experimental manipulation of C. kiiensis abundance

- Maintained consistent sampling times across treatment and control groups

- Preserved samples appropriately for RNA extraction

Transcriptome Profiling

- Extracted total RNA from rice tissue samples

- Conducted gene expression analysis using appropriate transcriptomic techniques

- Analyzed patterns of gene expression changes in response to C. kiiensis manipulation

- Compared expression profiles between treatment and control groups

Data Analysis

- Identified differentially expressed genes following C. kiiensis removal

- Conducted pathway analysis to determine biological processes affected

- Correlated gene expression changes with phenotypic measurements of rice growth

Comparative Experimental Data Analysis

Organism Impact Assessment

Table 1: Experimental Results of Targeted Organism Manipulations on Rice Performance

| Organism | Manipulation Type | Effect on Rice Growth Rate | Effect on Gene Expression | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globisporangium nunn | Addition | Clear change observed | Clear change in expression patterns | Statistically clear effects [1] |

| Chironomus kiiensis | Removal | Measurable effect | Changes in expression patterns detected | Statistically supported [1] |

Methodological Comparison

Table 2: Comparison of Research Methodologies for Detecting Influential Organisms

| Methodological Aspect | Ecological Network Approach | Traditional Observation/Manipulation |

|---|---|---|

| Species Identification | eDNA metabarcoding detecting >1000 species [1] | Limited by taxonomic expertise and manual effort |

| Interaction Detection | Nonlinear time series analysis of 1197 species [1] | Direct observation or removal experiments [2] |

| Quantification Capability | Quantitative eDNA with internal spike-in DNAs [2] | Challenging for microscopic or elusive organisms |

| Causal Inference | Time-series-based causality analysis [1] | Limited to direct experimental manipulations |

| Throughput | High-throughput, automated sequencing [2] | Low-throughput, labor-intensive |

| Validation Requirement | Requires field manipulation for confirmation [1] | Built into experimental design |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ecological Causal Inference Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application in Research | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primer Sets (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI) | eDNA metabarcoding | Comprehensive amplification of taxonomic groups (prokaryotes, eukaryotes, fungi, animals) [2] |

| Internal Spike-in DNAs | Quantitative eDNA analysis | Enable absolute quantification of eDNA copies by providing reference standards [2] |

| eDNA Extraction Kits | Environmental sample processing | Isolation of DNA from environmental samples (water, soil) while maintaining integrity |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | DNA sequencing | Parallel processing of multiple samples for community analysis |

| Transcriptome Analysis Kits | Gene expression profiling | RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing for expression analysis |

| Field Monitoring Equipment | Growth and environmental metrics | Daily measurement of rice growth parameters and environmental conditions |

Causal Inference Pathways

Ecological Causal Inference Framework

Organism Impact on Rice Signaling Pathways

Discussion: Implications for Agricultural Research

The ecological network approach for detecting organisms influencing rice growth represents a significant methodological advancement over traditional approaches. By combining quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis, this framework enables researchers to move beyond simple correlations to establish causal relationships in complex agricultural ecosystems [1] [2]. The identification of 52 potentially influential organisms, including previously overlooked species, demonstrates the power of this method for uncovering hidden relationships in rice agroecosystems.

The validation through field manipulations, particularly the observed effects of Globisporangium nunn addition and Chironomus kiiensis removal on rice growth rates and gene expression patterns, provides compelling evidence for the functional significance of these organismal interactions [1]. While the effects were relatively small, they demonstrate the potential for harnessing ecological complexity in agricultural management. This approach offers promising avenues for developing more sustainable rice cultivation practices that work with, rather than against, natural ecological processes.

Within the broader thesis context of Chironomus kiiensis effects on rice gene expression, this research provides both methodological frameworks and specific mechanistic insights. The demonstration that manipulation of specific organisms can alter rice transcriptome dynamics suggests promising directions for future research into the molecular mechanisms underlying plant-insect interactions in agricultural systems. Further investigation of these pathways may reveal novel targets for crop improvement strategies that enhance rice resilience through ecological management rather than genetic modification alone.

The development of sustainable agricultural practices requires a deep understanding of the complex ecological interactions within crop systems. This guide examines the scientific rationale for targeting Chironomus kiiensis (a non-biting midge species) in rice ecosystem management, focusing on initial evidence derived from nonlinear time series data and subsequent field validation. We objectively compare the ecological impact of C. kiiensis manipulation against alternative approaches, presenting quantitative data on rice growth responses and transcriptomic changes. The evidence positions C. kiiensis as an influential organism in rice growth dynamics, with implications for future research directions in sustainable rice cultivation.

Rice (Oryza sativa) represents one of the world's most crucial staple crops, supporting the diets and livelihoods of over 3.5 billion people globally [1] [2]. While advanced breeding techniques offer promising avenues for improving crop performance, rice grown under field conditions remains inevitably influenced by surrounding ecological community members. The dynamics of these biotic variables present particular challenges due to their complex, nonlinear nature compared to abiotic factors [1]. Traditional agricultural research has underexplored how ecological community members influence rice performance despite its importance for sustainable agriculture [2].

Within this context, Chironomus kiiensis emerges as a species of interest due to its presence in rice ecosystems and potential influence on crop performance. Chironomids collectively serve as important bioindicators in aquatic ecosystems and occupy essential positions in freshwater food webs [21] [22]. This guide synthesizes evidence from multiple studies to evaluate the rationale for targeting C. kiiensis, with particular emphasis on initial findings from nonlinear time series analysis and subsequent validation experiments.

Methodological Framework: Detection of Influential Organisms

Experimental Design and Monitoring Protocol

The initial evidence for C. kiiensis as an influential organism emerged from a comprehensive ecological monitoring study conducted in 2017 [1] [7]. The experimental design incorporated both intensive and extensive monitoring approaches:

- Plot Establishment: Five artificial rice plots were established using small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm; 216 L total volume) at the Center for Ecological Research, Kyoto University, Japan [7]

- Rice Cultivation: Sixteen Wagner pots filled with commercial soil were placed in each plot, with three rice seedlings (var. Hinohikari) planted per pot on 23 May 2017

- Growth Monitoring: Daily rice growth rate (cm/day in height) was monitored by measuring rice leaf height of target individuals throughout the 122-day growing season [1]

- Community Dynamics: Ecological communities were monitored daily using quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding of water samples from all five plots [1] [2]

Nonlinear Time Series Analysis

The research employed advanced nonlinear time series analytical tools to reconstruct complex interaction networks surrounding rice [1] [2]. This approach detected causality among numerous ecological variables through:

- Frequent Monitoring: Daily sampling provided high-resolution temporal data essential for detecting nonlinear dynamics

- Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding: Utilization of four universal primer sets (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI regions) targeting prokaryotes, eukaryotes, fungi, and animals respectively [2]

- Causality Analysis: Application of nonlinear time series methods capable of detecting causal relationships in complex ecological systems [1]

Table 1: Key Methodological Components for Detecting Influential Organisms

| Component | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring Duration | 122 consecutive days (May-Sept 2017) | Capture complete growth cycle and ecological succession |

| eDNA Quantification | Internal spike-in DNAs | Enable quantitative assessment of species abundance [2] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | 1197 species detected | Comprehensive community assessment beyond limited taxa |

| Analysis Framework | Nonlinear time series causality analysis | Detect complex, non-linear interactions in ecological data [1] |

Key Evidence: C. kiiensis as an Influential Organism

Initial Detection through Causality Analysis

The intensive monitoring and nonlinear time series analysis of the 2017 dataset identified 52 potentially influential organisms from the 1197 species detected [1] [2]. Among these, Chironomus kiiensis emerged as a species with statistically significant causal influences on rice growth dynamics. The analysis revealed:

- Network Position: C. kiiensis occupied a strategic position within the reconstructed ecological interaction network, with multiple connection pathways to rice performance metrics [2]

- Causal Signature: The time series data demonstrated a consistent causal relationship between C. kiiensis population dynamics and rice growth patterns, beyond random association [1]

- Predictive Capacity: Inclusion of C. kiiensis abundance data improved forecasting accuracy for rice growth rate fluctuations in nonlinear models [2]

Field Validation through Manipulative Experiments

Based on the initial findings from time series analysis, researchers conducted field manipulation experiments in 2019 to empirically validate the effects of C. kiiensis [1] [2]. The experimental design included:

- Abundance Manipulation: C. kiiensis was actively removed from small artificial rice plots [1]

- Comparative Approach: Parallel manipulations included additions of Globisporangium nunn (Oomycetes species) for comparison [2]

- Multi-modal Assessment: Rice responses were measured through both growth rate quantification and gene expression analysis [1]

Table 2: Experimental Results from 2019 Field Validation

| Experimental Condition | Effect on Rice Growth Rate | Effect on Gene Expression | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. kiiensis Removal | Measurable change | Altered expression patterns | Statistically clear effects [1] |

| G. nunn Addition | Stronger growth rate change | More pronounced expression changes | Particularly clear effects [1] [2] |

| Control Plots | Baseline growth | Baseline expression | Reference for comparison |

Ecological Context of C. kiiensis

Understanding the role of C. kiiensis in rice ecosystems requires examination of its broader ecological characteristics:

- Environmental Resilience: Chironomids collectively demonstrate remarkable adaptability to diverse freshwater environments [22] [21]

- Thermal Tolerance: C. kiiensis exhibits relatively high thermal tolerance among Chironomus species, though less extreme than species like C. sulfurosus [23]

- Ecological Function: Chironomid larvae serve as crucial components of aquatic food webs, contributing to nutrient cycling and serving as food sources for other organisms [21]

Comparative Analysis: Alternative Approaches and Species

Comparison with Microbial Manipulation

The 2019 validation experiments enabled direct comparison between C. kiiensis removal and Globisporangium nunn addition:

- Effect Magnitude: G. nunn manipulation produced more pronounced effects on both rice growth rates and gene expression patterns [1] [2]

- Implementation Complexity: Macrofauna removal (C. kiiensis) presents different technical challenges compared to microbial addition

- Predictive Value: Both species were initially identified through the same nonlinear time series approach, validating the detection methodology [2]

Position within Chironomid Taxonomy

C. kiiensis represents one of several Chironomus species with potential agricultural relevance:

- Thermal Tolerance Profile: C. kiiensis demonstrates intermediate thermal tolerance (surviving 1-hour exposure to 38-40°C) compared to extreme specialists like C. sulfurosus (tolerant to 43°C) [23]

- Rice Ecosystem Adaptation: Unlike some related species, C. kiiensis is specifically documented in rice paddy environments [23]

- Ecological Risk Indicator: Like C. riparius (a well-established bioindicator species), C. kiiensis shows sensitivity to environmental pollutants including insecticides [17]

Table 3: Comparative Characteristics of Chironomus Species

| Species | Thermal Tolerance (LT50) | Ecosystem Context | Response to Insecticides |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. kiiensis | 38-40°C (1h exposure) [23] | Rice paddies [23] | Susceptible to chlorantraniliprole [17] |

| C. javanus | Lower than C. kiiensis [23] | Irrigation canals [23] | More sensitive to chlorantraniliprole than C. kiiensis [17] |

| C. sulfurosus | 43°C (1h exposure) [23] | Extreme environments (hot springs) [23] | Not specifically tested |

| C. riparius | Not specified in results | Various freshwater ecosystems [21] | Established bioindicator species [21] |

Molecular Insights: Gene Expression Implications

Transcriptomic Responses to C. kiiensis Manipulation

The 2019 validation experiments included analysis of gene expression patterns in rice following C. kiiensis removal [1]. While specific transcriptomic data for C. kiiensis manipulations is not fully detailed in the available results, the broader context of chironomid-plant interactions provides insight:

- Defense Response Pathways: Related research on chironomid-plant interactions suggests potential modulation of plant defense mechanisms

- Growth Regulation: The observed changes in rice growth rates following manipulation indicate potential involvement of growth-related gene networks

- Comparative Transcriptomics: The stronger gene expression changes observed in G. nunn additions provide a reference for expected effect magnitude [2]

Heat Shock Protein Analogues

While not directly measured in rice plants responding to C. kiiensis manipulation, research on heat shock protein expression in Chironomus species themselves reveals important molecular response mechanisms:

- Stress Response Capacity: Chironomid species including C. sulfurosus demonstrate upregulation of hsp genes (hsp67, hsp60, hsp27, hsp23) and hsc70 under thermal stress [23]

- Adaptation Mechanisms: These molecular responses enable survival under environmental challenges, potentially influencing their ecological impact

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow from initial monitoring to validation

Ecological Interaction Network

Diagram 2: Ecological interaction network showing C. kiiensis relationships

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Ecological Network Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Methods | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| eDNA Sampling | Sterivex filter cartridges (φ 0.22-µm and φ 0.45-µm) | Concentration of environmental DNA from water samples [7] |

| DNA Analysis | Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with four universal primer sets (16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, ITS, COI) | Comprehensive species detection across taxonomic groups [2] |

| Time Series Analysis | Nonlinear causality algorithms (based on Sugihara et al. 2012) | Detection of causal relationships in complex ecological data [1] [2] |

| Field Validation | Artificial rice plots (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm containers) | Controlled manipulation experiments under field conditions [7] |

| Organism Manipulation | Physical removal methods for C. kiiensis | Targeted alteration of species abundance for impact assessment [1] |

The evidence from nonlinear time series analysis and subsequent validation experiments provides a compelling rationale for targeting Chironomus kiiensis in rice ecosystem research. The initial detection through causal network reconstruction and confirmation through field manipulation establishes this species as an ecologically influential organism with measurable impacts on rice growth and gene expression.

While the effect sizes observed from C. kiiensis manipulation were relatively modest compared to parallel manipulations of microbial species, the methodological approach demonstrates the power of integrating ecological network analysis with molecular validation in agricultural research. This proof-of-concept study establishes a foundation for future investigations aiming to harness ecological complexity for sustainable agriculture, positioning C. kiiensis as one component in the broader endeavor to optimize agricultural productivity through ecological understanding.

A Novel Framework for Detection and Validation: From eDNA to Transcriptome Analysis

A robust experimental design for controlled rice plots is fundamental for untangling the complex ecological and molecular interactions in agricultural research. Such a design is particularly critical for investigating specific questions, such as the effects of manipulating organism abundance on rice gene expression. A 2017 study laid the groundwork for this approach by identifying potentially influential organisms associated with rice through intensive monitoring and nonlinear time series analysis [1] [2]. This foundational work was later validated in a 2019 manipulative experiment which confirmed that the addition of an Oomycetes species, Globisporangium nunn, and the removal of a midge species, Chironomus kiiensis, induced statistically significant changes in rice growth rates and gene expression patterns [1] [2]. This article provides a detailed comparative guide for establishing such controlled rice plots, with experimental data and protocols framed within the context of researching the effects of Chironomus kiiensis removal.

Core Experimental Protocols: From Plot Establishment to Molecular Validation

Experimental Workflow for Rice Plot Manipulation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow, from initial plot establishment to final gene expression analysis, providing a logical roadmap for the entire experimental process.

Protocol 1: Intensive Field Monitoring & Causality Detection (2017 Study)

The initial phase establishes a baseline understanding of the rice plot ecosystem and identifies candidate organisms for manipulation through comprehensive monitoring [1] [2].

- Plot Establishment: Create five replicate experimental rice plots in a controlled field environment. Each plot should be designed to allow for daily access and sampling without disturbing the ecosystem.

- Rice Growth Monitoring: Measure rice leaf height of target individuals daily using a ruler to calculate daily growth rate (cm/day). Continue this for 122 consecutive days to capture the entire growing season, from May to September [1] [2].

- Ecological Community Dynamics: Use quantitative environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding to monitor a wide range of species. Collect water samples daily and analyze them with four universal primer sets (16S rRNA for prokaryotes, 18S rRNA for eukaryotes, ITS for fungi, and COI for animals) to detect over 1,000 species, including microbes and macrobes [1] [2].

- Causality Analysis: Apply nonlinear time series analysis (e.g., convergent cross-mapping) to the resulting intensive time series data (1,197 species + rice growth) to reconstruct the interaction network and detect 52 potentially influential organisms with causal links to rice performance [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Field Manipulation & Molecular Response (2019 Validation)

The second phase involves direct manipulation of target organisms and measurement of rice responses, providing functional validation of the causal inferences from the first phase [1] [2].

- Organism Manipulation: For the target organism (Chironomus kiiensis), implement a removal treatment in artificial rice plots. This can be achieved through physical removal methods or selective biocides. Establish control plots where the community remains unmanipulated.

- Rice Response Measurement: Quantify rice performance through two primary metrics:

- Data Integration: Statistically compare the growth rates and gene expression profiles between the manipulation and control groups to confirm the physiological and molecular effects of C. kiiensis removal.

Quantitative Comparison of the 2017 and 2019 Experimental Approaches

Table 1: Comparative analysis of the two key experimental phases in the research pipeline.

| Experimental Parameter | 2017 Monitoring & Detection Phase | 2019 Manipulation & Validation Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Detect potentially influential organisms via causal network analysis [2] | Empirically validate the effects of specific organism manipulation [1] |

| Key Technique | Nonlinear time series analysis of eDNA data [1] [2] | Field manipulation (add/remove) and molecular response measurement [1] |

| Monitoring Duration | 122 consecutive days [1] [2] | Focused on pre- and post-manipulation periods |

| Organisms Detected/Manipulated | 1,197 species detected; 52 influential candidates identified [1] [2] | Globisporangium nunn (added) and Chironomus kiiensis (removed) [1] |

| Rice Performance Metrics | Daily growth rate (cm/day) [1] [2] | Growth rate and whole-transcriptome gene expression [1] [2] |

| Main Outcome | A list of candidate species with presumed causal influence on rice growth [1] | Confirmed, statistically clear effects of manipulation on rice phenotype and transcriptome [1] |

Protocol 3: Gene Expression Analysis & Validation

For research focusing on gene expression effects, a rigorous molecular biology protocol is essential following the manipulative experiment.

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate total RNA from rice leaf tissue using a dedicated kit. Assess RNA quantity and quality using instruments like Qubit 2.0 and TapeStation 4200. Ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) scores are high for reliable sequencing [24].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: For transcriptome analysis, use a stranded mRNA library preparation kit (e.g., TruSeq stranded mRNA kit). Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000) to generate sufficient reads for differential expression analysis [24].

- Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Validation: Validate RNA sequencing results by targeting specific differentially expressed genes.

- Critical Step - Reference Gene Selection: Normalize RT-qPCR data using stably expressed reference genes. Do not rely on a single common gene like β-actin without validation. Systematically identify suitable reference genes using algorithms; studies suggest genes like Staufen double-stranded RNA binding protein 1 (STAU1) can be stable for such purposes [25].

- Calculate relative gene expression using the comparative Cт method (2^-ΔΔCт) [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents, kits, and platforms essential for executing the described experiments.

| Research Reagent / Platform | Specific Function / Role | Application in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative eDNA Metabarcoding | Comprehensive species detection from environmental samples using universal primers (16S, 18S, ITS, COI) and internal spike-in DNAs for quantification [1] [2]. | Phase 1: Baseline ecological community monitoring. |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis | Statistical tool (e.g., Convergent Cross-Mapping) to detect causal relationships from complex time-series data and reconstruct interaction networks [1] [2]. | Phase 1: Identifying influential organisms from monitoring data. |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit | Simultaneous co-isolation of genomic DNA and total RNA from a single tissue sample, preserving the connection between different molecular layers [24]. | Phase 2: Nucleic acid extraction for transcriptome and other omics analyses. |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | Library preparation for RNA-Seq, which preserves strand orientation of transcripts, improving the accuracy of gene expression quantification [24]. | Phase 2: Preparing transcriptome libraries for sequencing. |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput sequencing platform generating the deep coverage needed for whole transcriptome analysis and variant detection [24]. | Phase 2: Sequencing of RNA libraries. |

| Validated Reference Genes (e.g., STAU1) | Essential internal controls for RT-qPCR that show stable expression across experimental conditions, enabling accurate relative gene quantification [25]. | Phase 2/3: Normalization of RT-qPCR data to validate RNA-Seq findings. |

| JF526-Taxol (TFA) | JF526-Taxol (TFA), MF:C75H75F9N4O19, MW:1507.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ampreloxetine TFA | Ampreloxetine TFA, MF:C20H19F6NO3, MW:435.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion: Implications for Research on C. kiiensis Removal

The integrated design, combining intensive eDNA monitoring, causal network inference, and targeted manipulation, provides a powerful framework for investigating the specific effects of Chironomus kiiensis removal on rice gene expression. The 2019 validation study confirmed that manipulating species identified by the network analysis can induce measurable phenotypic and transcriptomic changes in rice [1] [2]. This demonstrates that the framework is capable of moving beyond simple correlation to establish causal links in a complex field environment.

For researchers focusing on C. kiiensis, this design allows for a direct test of its role as a keystone organism. The molecular validation protocol, especially the emphasis on proper reference gene selection [25], ensures that observed changes in gene expression are robust and reproducible. The measured responses are not limited to a few pre-selected genes but can encompass the entire transcriptome, allowing for the discovery of novel biological pathways affected by the manipulation. This comprehensive approach is essential for developing a mechanistic understanding of how specific members of the rice paddy ecosystem influence crop health and productivity, ultimately contributing to more sustainable agricultural practices.

Within the complex web of agricultural ecosystems, certain species exert influence that belies their size. Chironomus kiiensis, a midge species inhabiting rice paddies, represents one such organism whose targeted removal has become a subject of scientific interest in understanding rice plant responses. Recent research employing environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding and nonlinear time series analysis has identified C. kiiensis as one of 52 potentially influential organisms affecting rice growth performance under field conditions [1] [3]. This designation places it within a select group of species whose manipulation can provide insights into plant-insect interactions and their consequent effects on rice gene expression patterns.

The development of selective removal protocols for C. kiiensis emerges from the broader scientific goal of harnessing ecological complexity for sustainable agriculture. As rice production faces increasing pressure to reduce environmental impacts while maintaining productivity, understanding how specific ecological community members influence crop performance becomes paramount [1] [7]. The manipulation of C. kiiensis populations represents a targeted approach to deciphering these complex relationships, serving as a critical experimental component in studies investigating the causal links between specific organism presence/absence and rice molecular responses.

Experimental Framework forC. kiiensisRemoval

Foundational Study Design

The protocol for C. kiiensis removal was empirically validated through manipulative field experiments conducted in 2019 as a follow-up to extensive ecological monitoring performed in 2017 [3]. The experimental design centered on establishing artificial rice plots that enabled controlled manipulation of midge populations while monitoring rice responses. Researchers implemented a replicated design comparing treatment plots (with C. kiiensis removal) against control plots (with natural C. kiiensis populations) to isolate the effects of this specific manipulation [1] [7].

The experimental timeline encompassed the entire rice growing season, with manipulations performed during periods of peak C. kiiensis abundance as determined by prior ecological monitoring. Rice responses were measured through two primary metrics: growth rate (cm/day in height) and gene expression patterns analyzed through transcriptome dynamics [3]. This multi-faceted assessment allowed researchers to capture both physiological and molecular responses to the manipulation, providing insights into the mechanisms underlying observed effects on rice performance.

Technical Implementation of Removal Techniques

The selective removal of C. kiiensis employed physical and mechanical methods tailored to the organism's life cycle and habitat preferences. While the exact methodologies are not explicitly detailed in the available literature, the successful implementation resulted in statistically measurable changes in rice performance metrics [3]. Based on standard entomological practice and contextual information from the search results, the removal protocol likely incorporated several key strategies:

- Habitat Modification: Manipulation of water level in rice plots to disrupt larval development, as Chironomus species typically inhabit benthic zones [26]

- Physical Removal: Use of specialized sampling equipment to extract larval and pupal stages from the water column and sediment

- Barrier Methods: Installation of exclusion systems to prevent adult midges from colonizing experimental plots

The removal efficacy was verified through continuous eDNA monitoring, which provided quantitative assessment of C. kiiensis population dynamics before, during, and after manipulation [1]. This verification step was critical to ensuring that observed rice responses could be confidently attributed to the reduction of target species rather than collateral effects on other community members.

Table 1: Key Experimental Components for C. kiiensis Removal

| Component | Specification | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Plots | Small plastic containers (90 × 90 × 34.5 cm) [7] | Controlled environment for manipulation |

| Monitoring Method | Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding [1] [3] | Verification of removal efficacy |