Unlocking Fertility Clues: What Rat Reproductive Tissues Reveal About Health

Exploring the microscopic world of black rat reproductive organs and their implications for understanding fertility across species

Of Rats and Men: A Microscopic Journey

Imagine a sophisticated laboratory operating within the body of a common black rat (Rattus rattus), where tiny cellular factories work tirelessly to produce sperm, regulate hormones, and maintain reproductive health.

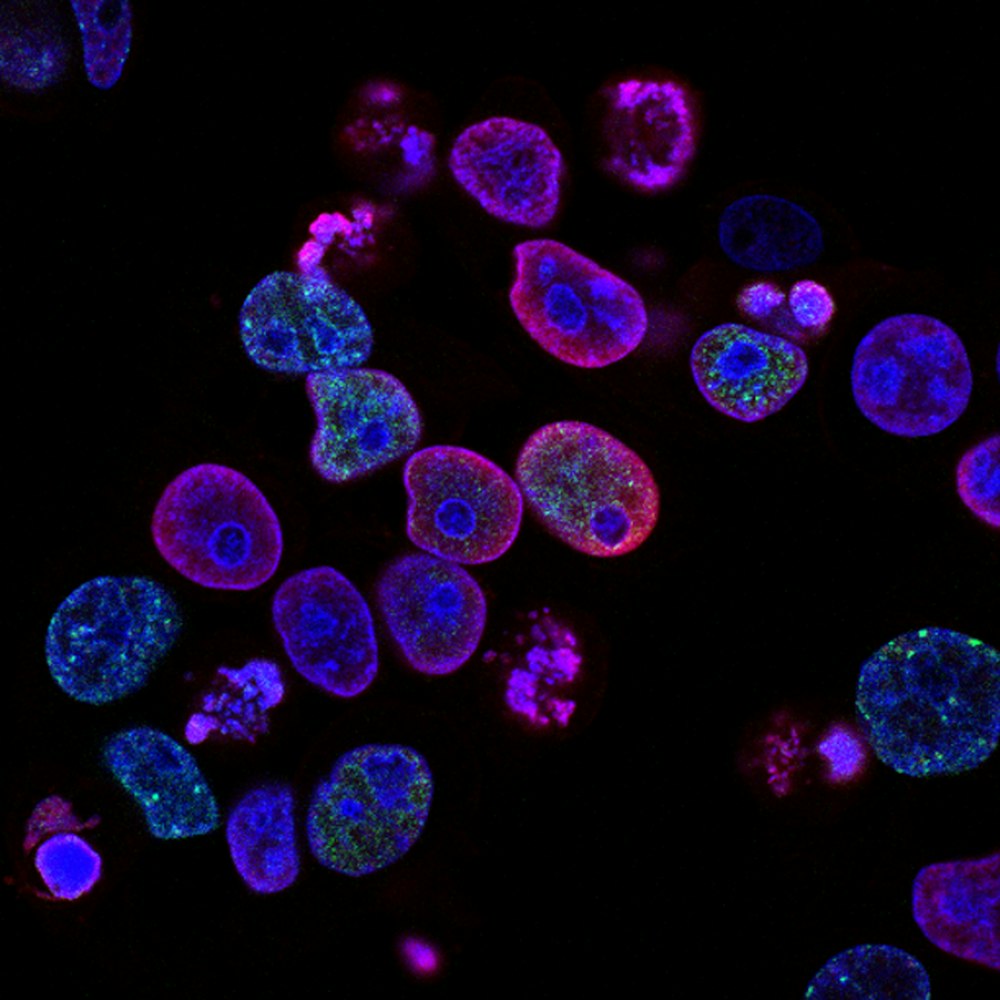

This laboratory's operational records are hidden in the intricate architecture of its reproductive tissues, waiting to be decoded under the microscope. Histological diagnosis—the microscopic examination of tissue structures—serves as our primary tool to interpret these records, revealing not only the health status of individual animals but also offering surprising insights into environmental impacts on mammalian reproduction.

For scientists, the black rat represents far more than just a common rodent; it's an invaluable biological model for understanding reproductive health across species. By studying the delicate tissues of rat testes, epididymis, and accessory glands, researchers can detect subtle changes caused by dietary factors, environmental toxins, and metabolic disorders.

Recent investigations have uncovered striking similarities between rat and human reproductive systems, making these findings particularly significant. Through the powerful lens of histology, we're learning that the story of reproduction written in rat tissues may hold crucial lessons for understanding fertility challenges far beyond the rodent world.

The Science of Microscopic Diagnosis: Reading Tissue Patterns

What is Histology?

At its core, histology is the scientific art of examining biological tissues at the microscopic level. To prepare reproductive organs for histological analysis, researchers follow an intricate process:

Tissue Collection & Fixation

Tissues are carefully collected and preserved in fixatives like formalin

Dehydration & Embedding

Tissues are dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax

Sectioning

Thin sections are cut using a microtome and mounted on slides

Staining

Special dyes highlight different cellular components

Why Histology Matters

When it comes to assessing reproductive health, histology provides unmatched insights that simply aren't available through other diagnostic methods.

Testes

Sperm production occurs here

Epididymis

Where sperm mature and are stored

Under normal conditions, rat testicular tissue shows well-organized seminiferous tubules with a thick layer of germ cells in various stages of development, healthy Leydig cells in the interstitial spaces producing testosterone, and an intact blood-testis barrier.

The Black Rat as a Biological Sentinel

The selection of Rattus rattus for reproductive studies is no accident. As noted in comparative longevity research, black rats provide an excellent comparative model to longer-lived rodent species like the blind mole rat, helping scientists identify what constitutes normal versus pathological tissue changes 6 .

Their relatively short reproductive cycle allows researchers to observe the effects of experimental conditions within manageable timeframes, while their physiological similarities to other mammals make findings potentially relevant across species.

Through meticulous histological analysis, scientists have established baseline parameters for healthy rat reproductive organs. These include specific measurements for seminiferous tubule diameter, epithelial height, and the arrangement of different cell types within the testis.

An In-Depth Look: How High-Fat Diets Alter Reproductive Tissues

The Experimental Design

A compelling recent study conducted by reproductive biologists sought to investigate how high-fat diets—similar to those increasingly consumed by humans—affect the microscopic structure of rat reproductive organs 2 . The researchers designed a rigorous experiment using male Wistar rats divided into three distinct groups:

Control Group

Standard feed

Overweight Group

10% fat diet

Obese Group

60% fat diet

Methodology

The methodology followed a systematic approach over several weeks:

- Euthanized the rats using approved ethical methods

- Carefully dissected and extracted reproductive organs

- Weighed the organs to calculate gonadosomatic indices

- Perfused the tissues with fixative

- Processed tissues through embedding and sectioning

- Examined prepared slides under light microscopy

- Conducted morphometric analyses using specialized software

Revelations Under the Microscope: Findings and Implications

The results of this investigation revealed striking alterations in the reproductive tissues of rats fed high-fat diets. While the control group displayed normal testicular architecture with well-organized spermatogenesis, the diet-induced overweight and obese groups showed progressive deterioration in testicular structure 2 .

Researchers observed vacuolization of the basal membrane, folding of the tubular wall, and a noticeable thinning of the seminiferous epithelium. Most concerning was the significant reduction in late spermatids—the developing sperm cells—in the obese group, suggesting impaired sperm production.

Histopathological Changes in Rat Reproductive Organs

| Organ/Parameter | Control Group | Overweight Group (10% fat) | Obese Group (60% fat) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testicular Architecture | Normal tubules with full spermatogenesis | 40% of tubules showed alterations | 96-100% of tubules affected |

| Seminiferous Epithelium Height | Normal height | Significant decrease | Variable with sloughing |

| Sperm in Tubular Lumen | Abundant | Reduced numbers | Markedly reduced |

| Epididymal Somatic Index | Normal | No significant change | Significantly decreased |

| Epididymal Epithelium | Tall cells with long stereocilia | Shorter cells with reduced stereocilia | Marked structural alterations |

Morphometric Changes in Rat Testes

| Parameter | Control Group | Overweight Group | Obese Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seminiferous Tubule Diameter (μm) | 280.5 ± 4.2 | 285.3 ± 3.8 | 296.7 ± 3.1* |

| Seminiferous Epithelium Height (μm) | 75.8 ± 1.5 | 70.2 ± 1.3* | 80.1 ± 1.7* |

| Lumen Diameter (μm) | 135.2 ± 3.8 | 145.8 ± 3.2* | 142.3 ± 3.5 |

* indicates statistically significant difference compared to control group (p < 0.001)

These findings demonstrate that both overweight and obesity induced by high-fat diets can directly damage the intricate architecture of rat reproductive organs. The epididymis was particularly vulnerable to dietary changes, showing altered function that likely contributes to the observed reductions in sperm viability and increases in sperm malformations 2 .

This research provides compelling histological evidence that nutrition plays a fundamental role in reproductive health, with excess dietary fat serving as a significant risk factor for impaired fertility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Resources for Reproductive Histology

Research Reagents and Materials

Conducting histological research on rat reproductive tissues requires specialized materials and reagents, each serving a specific purpose in the journey from fresh tissue to diagnostic slide.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Specific Application in Reproductive Histology |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin Solution | Tissue fixation | Preserves tissue architecture and prevents decomposition |

| Ethanol Series | Tissue dehydration | Removes water from tissues prior to paraffin embedding |

| Paraffin Wax | Tissue embedding | Provides structural support for thin sectioning |

| Hematoxylin Stain | Nuclear staining | Highlights cell nuclei in blue-purple tones |

| Eosin Stain | Cytoplasmic staining | Counterstains cytoplasm and connective tissue pink |

| Phosphotungstic Acid | Specialized staining | Enhances contrast in micro-CT imaging of musculature |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme digestion | Digests proteins during DNA extraction for genetic studies 6 |

These fundamental tools allow researchers to prepare reproductive tissues for detailed examination, revealing the hidden world of cellular structures that determine reproductive function. Additional specialized reagents might include antibodies for immunohistochemistry to identify specific cellular markers, or RNA preservation buffers for concurrent molecular studies.

Advanced Diagnostic Technologies

Beyond conventional histology, modern reproductive research employs increasingly sophisticated technologies to unravel the complexities of rat reproductive organs.

Transmission electron microscopy offers ultra-high magnification views of subcellular structures, allowing researchers to examine organelles like mitochondria within reproductive cells—a technique that has been used to study uterine changes during different phases of the estrous cycle in related rodent species 3 .

Another innovative approach is micro-computed tomography (μCT), which enables three-dimensional virtual histology of reproductive structures without the need for physical sectioning. In a groundbreaking application of this technology, scientists successfully visualized the complete muscular architecture of a rat uterus, mapping variations in muscle thickness and fiber orientation throughout the organ .

This advanced methodology provides a comprehensive view of tissue organization that would be incredibly time-consuming to reconstruct using traditional histological sections alone.

These technological advances, combined with the fundamental tools of histology, create a powerful diagnostic arsenal for understanding reproductive health in rat models. As these methods continue to evolve, they promise ever-deeper insights into the intricate relationship between tissue structure and reproductive function.

Conclusion: The Big Picture in Tiny Tissues

The histological examination of black rat reproductive organs reveals a compelling narrative about how lifestyle factors, environmental conditions, and physiological processes intersect at the cellular level.

Through the studies we've explored, particularly the investigation into high-fat diets, we've seen how reproductive tissues serve as sensitive indicators of overall health, responding to dietary challenges with structural changes that directly impact fertility. The vacuolization of testicular tubules, the thinning of seminiferous epithelium, and the altered epididymal environment all tell a consistent story: reproductive health is intimately connected to metabolic health.

These findings in rat models resonate far beyond the world of rodents. The structural similarities between rat and human reproductive systems mean that insights gained from histological studies of rat testes and epididymides may shed light on human fertility challenges. As obesity rates continue to rise globally, understanding how excess body fat impacts reproductive function becomes increasingly urgent. The histological evidence from rat studies provides a powerful visual argument for maintaining healthy lifestyles to preserve fertility.

Perhaps most importantly, the field of reproductive histology continues to evolve, with new technologies offering ever more detailed views of cellular structure and function. As researchers employ advanced techniques like three-dimensional imaging and molecular staining, our understanding of reproductive health will grow increasingly sophisticated.

The humble black rat, with its readily accessible reproductive tissues and well-characterized biology, will undoubtedly continue to play a crucial role in this journey of discovery—helping us read the secret language of reproductive health written in tissue patterns invisible to the naked eye.