Unlocking Marinisomatota: Metabolic Strategies, Functional Diversity, and Biotechnological Potential in Ocean Ecosystems

Marinisomatota (formerly Marinimicrobia or SAR406) are ubiquitous and abundant marine bacteria whose ecological roles and metabolic versatility are only beginning to be understood.

Unlocking Marinisomatota: Metabolic Strategies, Functional Diversity, and Biotechnological Potential in Ocean Ecosystems

Abstract

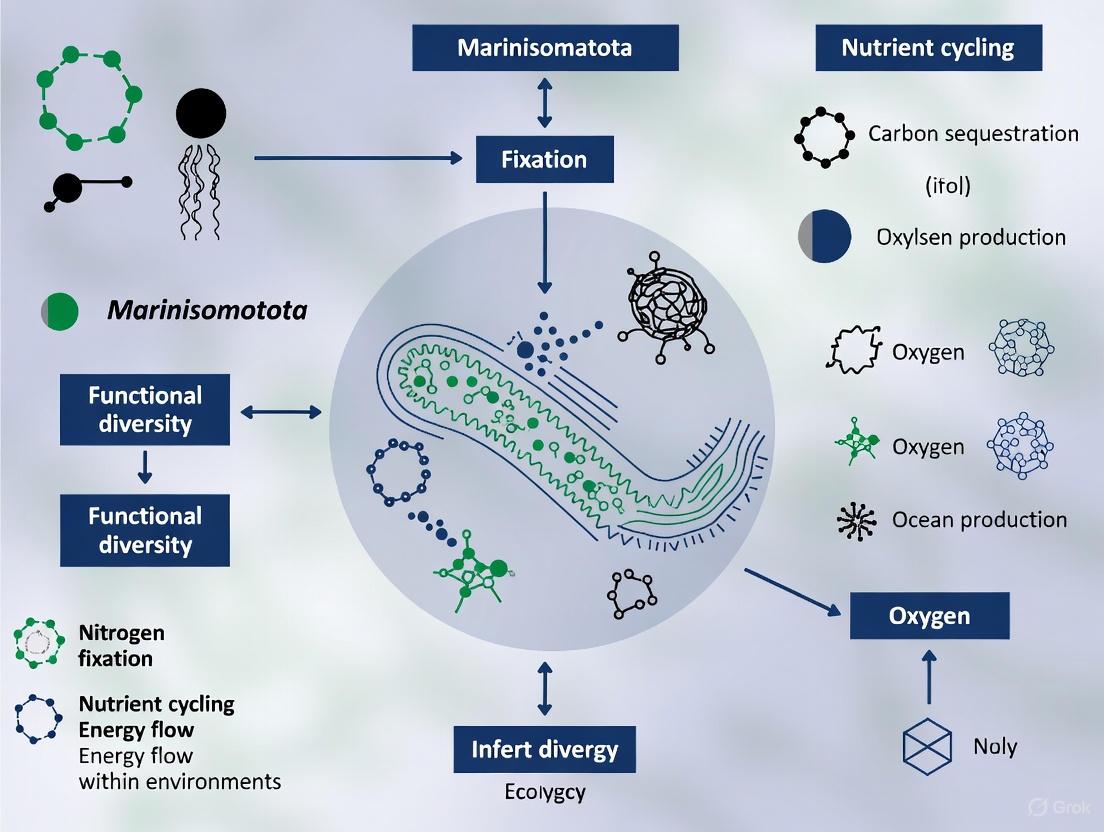

Marinisomatota (formerly Marinimicrobia or SAR406) are ubiquitous and abundant marine bacteria whose ecological roles and metabolic versatility are only beginning to be understood. This article synthesizes recent groundbreaking research on Marinisomatota, exploring their widespread distribution across global oceans and the discovery of three distinct metabolic strategies—photoautotrophic potential (MS0), heterotrophic with glycolysis (MS1), and heterotrophic without glycolysis (MS2)—that reveal a capacity for mixotrophy. We delve into the methodologies enabling the cultivation and genomic analysis of these previously uncultured microbes, address challenges in functional characterization, and compare their ecological niches with other marine phyla. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights how the unique functional diversity of Marinisomatota, including their adaptations to nutrient limitation and potential for novel compound production, positions them as a promising resource for future biotechnological and biomedical applications.

Who Are the Marinisomatota? Unveiling the Ecology and Evolutionary History of a Widespread Marine Phylum

The reclassification of the widespread marine bacterial group previously known as Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, and SAR406 to Marinisomatota represents a significant advancement in microbial taxonomy and ecology. This phylum-level rename reflects a substantial refinement in our understanding of its phylogenetic positioning and functional diversity within global ocean ecosystems. Marinisomatota are ubiquitous and abundant in marine environments, traditionally characterized as heterotrophic microorganisms [1] [2]. However, recent genomic investigations have revealed unexpected metabolic versatility, including light-dependent metabolic capabilities, that challenges previous ecological assumptions about this group [2].

This taxonomic clarification emerged from large-scale genomic analyses and the application of standardized classification systems such as the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB), which have revolutionized our ability to categorize previously unclassified marine microbial diversity [3] [4]. The reclassification to Marinisomatota provides a unified framework for studying this phylum's ecological role, particularly its contribution to carbon cycling across diverse oceanic provinces from surface waters to deep-sea sediments [1] [5]. Within the context of marine microbial ecosystem functioning, understanding the true taxonomic boundaries and metabolic capabilities of Marinisomatota is crucial for accurately modeling their contributions to global biogeochemical cycles.

Taxonomic History and Genomic Resolution

The Path to Reclassification

The journey to reclassification began with the initial discovery of these organisms through 16S rRNA gene sequencing from marine environments, where they were designated under multiple names including Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, and SAR406 [1] [2]. These provisional labels persisted for decades despite growing evidence of their phylogenetic coherence, primarily due to the challenges of cultivating these organisms in laboratory settings [3]. The turning point came with advances in metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) technologies that enabled researchers to reconstruct genomes directly from environmental samples without cultivation [6] [4].

The application of the candidate taxonomic unit (CTU) circumscription system along with standardized nomenclature finally provided the objective framework needed to properly delineate this phylum [3]. This approach, coupled with phylogenomic analyses using concatenated marker proteins, revealed that the previously used names referred to the same monophyletic lineage, necessitating the unified taxonomic designation Marinisomatota [1] [2]. This reclassification exemplifies how genomic approaches are resolving long-standing ambiguities in microbial taxonomy, particularly for environmentally abundant but uncultivated lineages [3] [4].

Current Taxonomic Structure

Comprehensive genomic surveys have elucidated the detailed taxonomic architecture within the Marinisomatota phylum. Through analysis of 1,588 Marinisomatota genomes retrieved from global ocean datasets, researchers have defined a structured hierarchy within this group [1] [2]:

Table: Taxonomic Classification of Marinisomatota Based on Genomic Analysis

| Taxonomic Rank | Diversity | Notable Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Marinisomatota | Formerly Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, SAR406 |

| Class | 1 | Not specified |

| Orders | 2 | Not specified |

| Families | 14 | S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, UBA8226 |

| Genera | 31 | Diverse lineages |

| Species | 67 | Multiple uncultivated species |

This taxonomic framework reveals substantial diversity within Marinisomatota, with members predominantly found in low-latitude marine regions where their relative abundances range from 0.18% to as high as 36.21% of the microbial community [1] [2]. The identification of 14 families provides a structured system for investigating the functional specialization and niche partitioning within this phylum.

Ecological Distribution and Biogeography

Marinisomatota demonstrate a remarkably broad distribution across marine ecosystems, from surface waters to deep-sea sediments [1] [5]. Their prevalence in the translucent zone and their presence across the transition to aphotic layers suggests adaptive strategies for coping with varying light regimes and nutrient availability [2]. Global mapping efforts using 16S rRNA gene surveys and metagenomic profiling have confirmed their cosmopolitan distribution across oceanic provinces, with distinct biogeographic patterns emerging relative to environmental parameters [3].

Notably, Marinisomatota are particularly abundant in low-latitude marine regions, though they maintain presence across diverse oceanic zones including polar environments [1] [4]. In hadal sediment ecosystems, such as the Mariana Trench, related groups show extraordinary novelty, with homogeneous selection and dispersal limitation emerging as dominant ecological drivers [7]. This pattern suggests that environmental filtering plays a crucial role in structuring Marinisomatota communities, with distinct evolutionary paths developing in isolated deep-sea environments compared to more connected surface waters.

The abundance and distribution of Marinisomatota position them as significant contributors to marine biogeochemical cycles. Their genomic capacity for diverse metabolic functions enables them to occupy multiple trophic levels, from primary production to organic matter degradation [2] [5]. This functional flexibility likely underpins their ecological success across the varied physicochemical gradients of the global ocean.

Metabolic Strategies and Functional Diversity

Marinisomatota exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity, with genomic evidence supporting three distinct trophic strategies [2]:

Table: Metabolic Strategies Identified in Marinisomatota

| Metabolic Strategy | Functional Characteristics | Ecological Niche |

|---|---|---|

| MS0 | Photoautotrophic potential with Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169) | Translucent zone, transitioning to aphotic layers |

| MS1 | Heterotrophic with pronounced glycolytic pathway | Organic-rich regions, participating in carbon cycling |

| MS2 | Heterotrophic without glycolysis | Nutrient-limited regions, alternative energy acquisition |

This metabolic diversity challenges the traditional characterization of Marinisomatota as strictly heterotrophic and reveals a continuum of trophic strategies that likely represents adaptive responses to nutrient limitations and light availability in different oceanic provinces [2]. Among the 14 identified families, five (S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, and UBA8226) exhibit genetic potential for light-dependent processes associated with Crassulacean acid metabolism, suggesting previously unrecognized phototrophic capabilities [1] [2].

Macromolecule Degradation Capabilities

Beyond their metabolic versatility in energy acquisition, Marinisomatota play significant roles in the marine carbon cycle through their capacity to degrade complex organic matter. Genomic analyses reveal extensive repertoires of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), with some MAGs containing up to 35 different glycoside hydrolases often in multiple copies, along with seven extracellular CAZymes, six polysaccharide lyases, and multiple sugar transporters [5].

This enzymatic machinery enables certain Marinisomatota lineages to degrade a broad spectrum of polysaccharides including chitin, cellulose, pectin, alginate, chondroitin, and carrageenan [5]. This metabolic capacity positions them as key participants in the breakdown of abundant necromass macromolecules in marine sediments, coupling organic matter remineralization with nutrient cycling [5]. The variation in genomic capacity for macromolecule degradation among different Marinisomatota lineages suggests niche specialization, with some populations specializing in particular substrate classes while others maintain broader metabolic capabilities.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Genomic Reconstruction and Analysis

The investigation of Marinisomatota has relied heavily on culture-independent approaches due to the historical challenges in cultivating these organisms. Standard methodologies for genomic reconstruction and analysis include:

- Metagenomic Assembly: Recovery of genomes directly from environmental sequences using tools such as MEGAHIT, MetaSPAdes, or IDBA-UD, followed by binning approaches including MaxBin, MetaBAT, and CONCOCT [6] [4].

- Genome Quality Assessment: Evaluation of MAG completeness and contamination using CheckM or similar tools, with medium-quality thresholds typically set at >50% completeness and <10% contamination [6].

- Phylogenomic Analysis: Construction of phylogenetic trees using concatenated marker gene sets (37-56 proteins) with maximum likelihood methods implemented in RAxML or IQ-TREE [6].

- Taxonomic Classification: Assignment using GTDB-Tk against the Genome Taxonomy Database, which has been instrumental in standardizing taxonomic placement across studies [1] [4].

- Metabolic Reconstruction: Prediction of metabolic pathways and functional capabilities through tools such as METABOLIC, KEGG, and EggNOG, complemented by manual curation of key pathways [2] [5].

These approaches have enabled the reconstruction of 1,588 Marinisomatota genomes from global ocean datasets, providing the comprehensive genomic foundation upon which current understanding of this phylum is built [1] [2].

Experimental Validation of Metabolic Capabilities

While cultivation remains challenging, innovative enrichment approaches have enabled experimental validation of Marinisomatota metabolic functions:

- Macromolecule Amendment Studies: Sediment samples are amended with specific macromolecules (proteins, polysaccharides, nucleic acids, or lipids) under different redox conditions to stimulate growth of specialized degraders [5].

- Metatranscriptomic Profiling: RNA sequencing from environmental samples or enrichments to identify actively expressed genes and pathways under in situ conditions [2].

- Geochemical Monitoring: Coupling genomic approaches with measurements of process rates, such as hydrogen production from fermentation or sulfate reduction, to link genetic potential with biogeochemical function [5].

These experimental approaches have been crucial for moving beyond genomic predictions to demonstrate the actual ecological roles of Marinisomatota in marine ecosystems.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Marinisomatota Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | SILVA SSU Ref, GTDB, KEGG, METABOLIC | Taxonomic classification, functional annotation, and metabolic pathway prediction |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GTDB-Tk, CheckM, METABOLIC, anvi'o | Genome quality assessment, phylogenetic placement, metabolic profiling |

| Enrichment Substrates | Polysaccharides (chitin, cellulose, carrageenan), proteins, lipids | Selective cultivation and metabolic capability testing |

| Sequence Analysis | Fastp, CD-HIT, DIAMOND, RAxML | Data preprocessing, clustering, homology search, phylogenetic reconstruction |

| Visualization Platforms | anvi'o, iTOL, Graphviz | Data integration, tree visualization, workflow illustration |

These resources have been instrumental in advancing our understanding of Marinisomatota biology, enabling researchers to overcome the challenges posed by their uncultivability and revealing their unexpected metabolic complexity and ecological significance.

The reclassification from Marinimicrobia/SAR406 to Marinisomatota represents more than just a taxonomic revision—it signifies a fundamental shift in our understanding of this phylum's ecological and functional significance in ocean ecosystems. The recognition of their metabolic versatility, including both heterotrophic and phototrophic capabilities, positions Marinisomatota as key players in marine carbon cycling with adaptations that enable them to thrive across diverse oceanic niches.

Future research directions should focus on overcoming the cultivation barriers that have limited physiological studies of Marinisomatota. Innovative cultivation approaches, such as diffusion-based chambers and targeted enrichment strategies, may finally enable laboratory-based investigation of their metabolic capabilities and regulatory mechanisms [8]. Additionally, single-cell genomic approaches coupled with metatranscriptomic and metaproteomic analyses under in situ conditions will provide deeper insights into their active metabolic roles in different ocean provinces.

As genomic databases continue to expand and analytical methods improve, further refinement of the Marinisomatota taxonomy is expected, potentially revealing additional diversity and functional specialization within this phylum. Understanding the evolutionary drivers behind their metabolic plasticity and the ecological implications of their mixotrophic strategies will be crucial for accurately modeling their contributions to ocean biogeochemistry and ecosystem functioning in a changing global climate.

The phylum Marinisomatota represents a group of uncultured bacteria whose ecological role in marine systems remains largely enigmatic. Framed within a broader thesis on functional diversity, this technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on Marinisomatota's biogeography and postulated functions. Genomic evidence suggests that a core set of microbial taxa, potentially including lineages like Marinisomatota, is crucial for ocean ecosystem functioning [9]. Their distribution and abundance patterns are tied to global biogeochemical cycles, and understanding their functional diversity is key to predicting ocean responses to environmental change.

Functional Diversity and Genomic Traits of Marine Microbiota

The functional capacity of a microbial community can be effectively proxied by analyzing its genomic content. One established method uses Clusters of Orthologous Groups functional categories (COG-FCs) to describe genomic contents, allowing for quantitative comparisons across diverse microbial lineages [10].

Quantitative Partitioning of Functional Traits

Research quantifying the variance in metabolic potential explained by taxonomy reveals that, on average, 41.4% of the variation in COG-FC relative abundance is accounted for by taxonomic rank [10]. The variance contributed by each rank is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Variance in Metabolic Potential Explained by Taxonomic Rank [10]

| Taxonomic Rank | Percentage of Variance Explained |

|---|---|

| Domain | 3.2% |

| Phylum | 14.6% |

| Class | 4.1% |

| Order | 9.2% |

| Family | 4.8% |

| Genus | 5.5% |

Relevance for Marinisomatota

Although specific COG-FC data for Marinisomatota is not yet available in the searched literature, this phylum is identified as one of 26 phyla represented in a broad genomic analysis, comprised entirely of uncultured lineages [10]. The aforementioned quantitative framework provides a methodology for future research to place Marinisomatota within a functional context across the bacterial tree of life. The strong phylogenetic signal in functional traits suggests that the metabolic capabilities of Marinisomatota can be inferred through its taxonomic placement.

Biogeographic Patterns of Core Marine Microbiota

Long-term time-series studies are critical for identifying core marine microbiota and understanding their dynamics.

Defining the Core Microbiota

In a decade-long study of a Mediterranean coastal site, the core microbiota was stringently defined based on both persistence and strong species associations. Core members were present in >30% of monthly samples over 10 years and possessed the strongest associations within the community network [9]. This interconnected core was relatively small, comprising 259 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) with 1,411 strong associations, most of which (~95%) were positive [9].

Seasonal Dynamics and Community Interaction

The core microbiota exhibits predictable seasonal succession. In the Mediterranean observatory, the richness and abundance of core OTUs increased in colder, mixed waters and decreased in stratified, warmer waters [9]. Winter communities featured subnetworks with the highest connectivity, with groups of highly associated taxa showing a preference for the same season [9]. This suggests that potential microbial interactions are more deterministic in winter than in other seasons. Furthermore, hub species with high connectivity were identified, indicating their potential keystone ecological roles [9].

Table 2: Characteristics of a Core Marine Microbiota from a 10-Year Study [9]

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | Present in >30% of monthly samples over 10 years & having the strongest associations |

| Total Core OTUs | 259 (182 Bacteria, 77 Protists) |

| Total Strong Associations | 1,411 |

| Nature of Associations | ~95% Positive |

| Seasonal Preference of Most Core OTUs | Mostly Winter |

| Season with Highest Network Connectivity | Winter |

Methodologies for Biogeographic and Functional Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Long-Term Time-Series Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying and characterizing an interconnected core microbiota, as applied in a 10-year marine coastal study [9].

- Sample Collection: Seawater samples are collected regularly (e.g., monthly) from a fixed observatory site over an extended period.

- Size Fractionation and DNA Extraction: Water is sequentially filtered through membranes to capture different organismal size fractions (e.g., 0.2-3 μm for pico-plankton, 3-20 μm for nano-plankton). DNA is extracted from the filters.

- Amplicon Sequencing: For community composition, the 16S rRNA gene (for bacteria and archaea) and the 18S rRNA gene (for protists) are amplified and sequenced using high-throughput sequencing platforms.

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Sequence Denoising: Raw sequences are processed into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) to achieve high resolution.

- Taxonomic Classification: ASVs are assigned taxonomy against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, PR2).

- Defining Resident and Core Microbiota:

- Resident OTUs: Filter OTUs present in more than a defined threshold (e.g., 30%) of all temporal samples.

- Core Microbiota: Subject resident OTUs to network analysis and define the core as those with the strongest associations.

- Network Analysis:

- Association Inference: Calculate robust correlations (e.g., using SparCC) between the relative abundances of all resident OTUs to infer potential interactions.

- Network Construction and Analysis: Build an association network where nodes are OTUs and edges represent significant correlations. Analyze network topology to identify hub taxa and modules (highly interconnected groups).

- Statistical Integration: Relate community turnover and core network dynamics to measured environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, nutrients, chlorophyll-a).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Protocol: Quantifying Function-Taxonomy Relationships

This methodology details the approach for quantifying how microbial functional traits are partitioned across taxonomic ranks [10].

- Genome Database Curation: Compile a large set of high-quality microbial genomes from diverse public databases (e.g., RefSeq, IMG/M, GenBank).

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign a consistent taxonomy to all genomes using a standardized system like the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB).

- Functional Annotation:

- Predict open reading frames (ORFs) from all genomes.

- Annotate ORFs by assigning them to Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs).

- Categorize COGs into functional categories (COG-FCs).

- Data Matrix Construction: Create a matrix where rows are genomes, columns are COG-FCs, and values are the relative abundances of each COG-FC within a genome.

- Variance Partitioning Analysis: Perform statistical analysis (e.g., hierarchical PERMANOVA) to quantify the proportion of variance in the COG-FC matrix explained by each taxonomic rank (domain to genus).

The workflow for this analysis is structured as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Marine Microbiome Biogeography Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filters (e.g., 0.2µm, 3µm, 20µm pore sizes) | Sequential size-fractionation of microbial plankton communities from seawater samples prior to DNA extraction [9]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater Kit) | Isolation of high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from environmental water filters for downstream molecular applications [9]. |

| PCR Reagents (e.g., high-fidelity DNA polymerase, dNTPs) | Amplification of phylogenetic marker genes (16S and 18S rRNA) with minimal error for preparation of amplicon sequencing libraries [9]. |

| Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) Database | A comprehensive database of orthologous protein groups used for functional annotation of predicted genes from genomic or metagenomic data [10]. |

| SparCC (Sparse Correlations for Compositional data) Algorithm | A statistical tool designed to infer robust correlation networks from compositional data (like 16S/18S amplicon or metagenomic data), mitigating spurious correlations [9]. |

| Mal-PEG4-Val-Cit-PAB-MMAE | Mal-PEG4-Val-Cit-PAB-MMAE, MF:C73H115N11O19, MW:1450.8 g/mol |

| Epimedin A (Standard) | Epimedin A (Standard), MF:C39H50O20, MW:838.8 g/mol |

The global biogeography of marine microbes is characterized by structured patterns of abundance and function. The phylum Marinisomatota, while currently underexplored, exists within this structured ecological context. Evidence from other microbial groups shows that functional traits are strongly linked to phylogeny and that a core, interconnected microbiota persists over time, driving essential ecosystem functions. The experimental and analytical frameworks outlined here provide a pathway for future research to decrypt the specific functional role of Marinisomatota and its contribution to the vast functional diversity of the global ocean.

Marinisomatota (formerly recognized as Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, and SAR406) represent a ubiquitous and abundant microbial lineage in global oceans, playing critical yet poorly understood roles in marine biogeochemical cycles. Recent genomic investigations have revealed that this phylum exhibits remarkable metabolic plasticity, allowing it to colonize diverse marine habitats from surface waters to the deep sea. This whitepaper delineates three distinct metabolic strategies—MS0 (photoautotrophic potential), MS1 (heterotrophic with pronounced glycolytic pathway), and MS2 (heterotrophic without glycolysis)—identified through comprehensive analysis of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data. Within the context of marine ecosystem functioning, understanding these strategies provides crucial insights into how microbial communities adapt to nutrient limitations and contribute to carbon processing in the world's oceans, with potential applications in biotechnology and drug discovery.

Marinisomatota represents one of the most abundant and widespread bacterial phyla in global marine environments, found from surface waters to hadal sediments with relative abundances ranging from 0.18% to 36.21% across different oceanic provinces [2]. Traditionally characterized as heterotrophic microorganisms, recent discoveries have revealed unexpected metabolic capabilities that challenge this simplistic classification. The phylum encompasses tremendous diversity, with recent studies identifying 1,588 Marinisomatota genomes representing one class, two orders, 14 families, 31 genera, and 67 species [2].

These microorganisms are predominantly distributed in low-latitude marine regions and exhibit distinct depth stratification patterns, with certain families showing preferences for specific oceanic layers including the oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) and bathypelagic waters [2] [11]. Genomic analyses of Marinisomatota populations in the northeastern Indian Ocean revealed their significant presence in OMZ and bathypelagic layers, where they potentially contribute to carbon cycling under hypoxic conditions [11]. Their distribution patterns and metabolic capabilities position Marinisomatota as key players in marine ecosystem functioning, particularly in the context of nutrient scavenging and energy transduction across redox gradients.

The identification of three core metabolic strategies (MS0, MS1, MS2) within this phylum represents a significant advancement in understanding how microbial communities maintain functional diversity in response to environmental constraints. These strategies emerge as evolutionary adaptations to nutrient limitations prevalent in vast oceanic regions, enabling Marinisomatota to exploit various ecological niches through specialized metabolic configurations [2].

The Three Core Metabolic Strategies

Genomic analyses of globally distributed Marinisomatota populations have revealed three distinct metabolic strategies characterized by specific genetic compositions and functional capabilities. These strategies represent adaptations to different ecological niches and nutrient availability conditions in the marine environment.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Marinisomatota Metabolic Strategies

| Metabolic Strategy | Trophic Mode | Key Genetic Features | Environmental Preference | Ecological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS0 | Photoautotrophic potential | Genes for Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169) | Translucent zone, transitioning between translucent and aphotic layers | Light-dependent carbon fixation, organic compound synthesis |

| MS1 | Heterotrophic with pronounced glycolytic pathway | Complete or enhanced glycolytic pathway | Regions with available organic matter | Efficient processing of organic carbon through glycolysis |

| MS2 | Heterotrophic without glycolysis | Lacks glycolytic pathway | Nutrient-limited environments | Alternative carbon processing pathways |

MS0: Photoautotrophic Potential

The MS0 strategy represents a remarkable departure from the traditionally heterotrophic lifestyle attributed to Marinisomatota. This strategy is characterized by the genetic potential for light-dependent processes associated with Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) [2]. Specifically, five Marinisomatota families (S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, and UBA8226) possess the genetic machinery necessary for this metabolic strategy, enabling them to potentially harness light energy for carbon dioxide fixation and synthesis of organic compounds [2].

This photoautotrophic capability allows MS0 strategists to thrive in the translucent zone and transition areas between light-rich and aphotic layers, where they can leverage both light energy and organic carbon sources. The presence of this metabolic strategy in a bacterial phylum previously considered exclusively heterotrophic underscores the metabolic versatility of Marinisomatota and challenges traditional classification schemes in marine microbiology. The CAM-like pathways suggest potential adaptations to diurnal cycling or fluctuating energy availability in the water column.

MS1: Heterotrophic with Pronounced Glycolytic Pathway

The MS1 strategy represents a specialized heterotrophic lifestyle characterized by a pronounced and efficient glycolytic pathway for carbon processing [2]. Organisms employing this strategy possess complete or enhanced glycolytic capabilities, allowing them to efficiently catabolize organic carbon sources through Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas or related glycolytic pathways.

This metabolic configuration is particularly advantageous in marine environments with moderate to high availability of organic substrates, where efficient glycolytic processing can provide competitive advantages. The MS1 strategists likely play significant roles in the processing of dissolved organic matter in the water column, contributing to carbon cycling in mesopelagic and bathypelagic zones where Marinisomatota are frequently abundant [11].

MS2: Heterotrophic without Glycolysis

The MS2 strategy represents an alternative heterotrophic approach that operates without conventional glycolytic pathways [2]. This strategy suggests the presence of alternative carbon processing mechanisms that bypass classical glycolysis, potentially including Entner-Doudoroff pathways, pentose phosphate pathways, or other novel carbohydrate degradation routes.

This metabolic configuration may provide advantages in nutrient-limited environments where conventional glycolytic substrates are scarce or where alternative pathways offer thermodynamic or kinetic benefits under specific environmental conditions. The presence of this strategy highlights the metabolic innovation within the Marinisomatota phylum and underscores the potential for novel biochemical pathways in marine microbial communities.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genomic and Metatranscriptomic Analysis

The identification and characterization of Marinisomatota metabolic strategies rely heavily on integrated omics approaches. The experimental workflow typically involves sample collection across environmental gradients, nucleic acid extraction, sequencing, and computational analysis.

Table 2: Key Methodological Approaches for Studying Marinisomatota Metabolic Strategies

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application in Marinisomatota Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | CTD rosette sampling, filtration | Depth-resolved sampling from surface to bathypelagic zones |

| DNA/RNA Extraction | Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method | Recovery of high-quality nucleic acids from filters |

| Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq platforms, 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomic sequencing | Assessment of community structure and functional potential |

| Genome Reconstruction | Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) binning and refinement | Recovery of population genomes from complex communities |

| Functional Annotation | KEGG Orthology (KO) groups, pathway analysis (e.g., M00169 for CAM) | Determination of metabolic capabilities and strategy classification |

The specific protocol for investigating Marinisomatota diversity and metabolic potential involves several critical steps [11]:

Sample Collection and Processing: Seawater samples are collected from various depths (surface, Deep Chlorophyll Maximum (DCM), Oxygen Minimum Zone (OMZ), and bathypelagic layers) using CTD rosette systems. Samples are typically pre-filtered through 20 μm nylon mesh to exclude larger organisms, followed by concentration onto 0.22 μm pore size polycarbonate filters.

DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Microbial DNA is extracted using the phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method. For community structure analysis, the V4-V5 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene are amplified using universal primer pairs (515Y/926R) and sequenced on Illumina platforms. For metagenomic analysis, qualified DNA samples are fragmented and subjected to shotgun sequencing.

Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) Construction: Sequencing reads are assembled into contigs, followed by binning to reconstruct individual genomes. MAGs are refined using criteria including completeness ≥50% and contamination ≤10%, with high-quality MAGs defined as those with completeness >90% and contamination <5%.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Recovered MAGs are functionally annotated using databases such as KEGG and MetaCyc. Specific metabolic capabilities are assessed through identification of key marker genes and pathways, such as those involved Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169) for MS0 strategists or glycolytic pathways for MS1 strategists.

Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics for Functional Validation

While genomic approaches predict metabolic potential, stable isotope resolved metabolomics (SIRM) can experimentally validate metabolic activities [12]. The Ion Chromatography-Ultrahigh Resolution-MS1/Data Independent-MS2 (IC-UHR-MS1/DI-MS2) method provides powerful capabilities for tracking the transformations of individual tracer atoms from precursors to products [12]. This approach enables determination of tracer atom position(s) in metabolite moieties with higher resolution and sensitivity than NMR methods.

The experimental protocol for SIRM analysis involves [12]:

Tracer Incubation: incubation of environmental samples or enrichment cultures with stable isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., [13C6]-glucose, [13C5,15N2]-glutamine).

Metabolite Extraction: Rapid quenching of metabolism followed by organic solvent-based extraction using methods such as methanol/chloroform/water extraction for comprehensive coverage of polar and non-polar metabolites.

IC-UHR-MS1/DI-MS2 Analysis: Separation using ion chromatography coupled to ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry, enabling resolution of minute mass differences (e.g., Δmass = 0.006995 amu between 13C and 15N).

Data Interpretation: Isotopologue distributions are calculated from peak area ratios after natural abundance correction, providing insights into metabolic pathway activities.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Marinisomatota Metabolic Strategy Classification

Ecological Drivers and Functional Significance

The emergence of three distinct metabolic strategies within Marinisomatota populations represents adaptive responses to environmental heterogeneity and nutrient limitations in marine ecosystems [2]. The distribution of these strategies follows clear biogeographic patterns influenced by factors such as light availability, dissolved oxygen concentrations, and organic matter quality.

In the global ocean, microbial communities are shaped by complex ecological processes including homogeneous selection (HoS) and dispersal limitation (DL) [7]. Analysis of hadal zone sediments revealed that homogeneous selection (accounting for 50.5% of community assembly) favors streamlined genomes with key functions for environmental adaptation, while dispersal limitation (43.8%) promotes versatile metabolism with larger genomes [7]. These evolutionary pressures likely contribute to the diversification of metabolic strategies observed in Marinisomatota.

The functional significance of this metabolic diversification extends to broader ecosystem processes. Marine zooplankton, particularly copepods, exhibit functional diversity patterns that influence carbon export efficiency [13]. Similarly, the metabolic strategies of microorganisms like Marinisomatota likely contribute to carbon processing and export in the oceans. Climate change is projected to promote trait homogenization in marine communities, which may reduce biomass and carbon export efficiency globally [13]. Understanding the metabolic versatility of key bacterial groups like Marinisomatota therefore becomes crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change.

Figure 2: Ecological Drivers and Functional Significance of Metabolic Diversification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of Marinisomatota metabolic strategies requires specific reagents, instruments, and computational tools. The following table summarizes essential components of the methodological toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Marinisomatota Metabolic Studies

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Equipment | CTD rosette systems with Niskin bottles | Depth-resolved seawater collection | SBE-911 Plus CTD profiler [11] |

| Filtration Materials | 20 μm nylon mesh, 0.22 μm polycarbonate filters | Microbial biomass concentration | Sefar Nitex mesh, Millipore filters [11] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol | DNA/RNA extraction from environmental samples | Standard molecular biology reagents [11] |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina sequencing kits, 16S rRNA primers (515Y/926R) | Library preparation and amplification | Illumina HiSeq 2500 chemistry [11] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | [13C6]-glucose, [13C5,15N2]-glutamine | Metabolic pathway tracing in SIRM | 13C-labeled substrates [12] |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents | Methanol, chloroform, water | Biphasic extraction of polar and non-polar metabolites | MeOH/CHCl3/H2O extraction [14] |

| Computational Tools | Metagenomic assembly software (e.g., Met4DX) | 4D peak detection in metabolomics | Met4DX for LC-IM-MS data [15] |

| Bioinformatics Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, HMDB, GTDB | Functional annotation and taxonomic classification | Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) [11] |

| AZM475271 | AZM475271, CAS:890808-56-7, MF:C28H22ClNO4, MW:471.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5,6-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-d11 | 5,6-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-d11, MF:C20H32O3, MW:331.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced computational tools have become increasingly important for analyzing complex metabolomics data. For example, Met4DX provides an end-to-end computational framework for peak detection, quantification and identification of metabolites in ion mobility-resolved untargeted metabolomics [15]. This tool employs a mass spectrum-oriented bottom-up assembly algorithm that significantly improves peak detection coverage and sensitivity, enabling researchers to detect and differentiate co-eluted metabolite isomers with small differences in chromatographic and ion mobility dimensions [15].

For metabolite annotation, two-layer interactive networking approaches such as MetDNA3 integrate data-driven and knowledge-driven networks to enhance annotation coverage and accuracy [16]. This strategy uses a comprehensive metabolic reaction network curated using graph neural network-based prediction of reaction relationships, enabling annotation of over 1,600 seed metabolites with chemical standards and more than 12,000 putatively annotated metabolites through network-based propagation [16].

The identification of three core metabolic strategies (MS0, MS1, MS2) within the Marinisomatota phylum represents a significant advancement in understanding functional diversity in marine microbial ecosystems. These strategies reflect adaptive responses to environmental heterogeneity and nutrient limitations prevalent in global oceans. The photoautotrophic potential of MS0 strategists, the efficient heterotrophy of MS1, and the alternative carbon processing of MS2 collectively contribute to the ecological success of Marinisomatota across diverse marine habitats.

Future research should focus on several critical directions. First, experimental validation of predicted metabolic capabilities through cultivation-based studies and stable isotope probing approaches will be essential to confirm the functional significance of these genetic potentials. Second, investigation of how these metabolic strategies respond to environmental changes, including ocean warming, deoxygenation, and acidification, will improve predictive models of ecosystem functioning. Third, exploration of the biotechnological potential of novel enzymes and pathways identified in Marinisomatota genomes may yield valuable tools for industrial applications and drug discovery.

The integration of advanced analytical techniques, including ion mobility-mass spectrometry and network-based metabolite annotation, with traditional microbial ecology approaches will continue to reveal novel aspects of microbial metabolic versatility. As these methodologies advance, our understanding of the complex relationships between microbial functional diversity and ecosystem processes in the oceans will continue to deepen, potentially revealing new fundamental principles governing life in marine environments.

Mixotrophy as a Survival Strategy in Nutrient-Limited Oceans

Mixotrophy, the combination of autotrophic and heterotrophic modes of nutrition in a single organism, represents a fundamental survival strategy that challenges the traditional dichotomy between producers and consumers in marine ecosystems. In the nutrient-impoverished waters of the oligotrophic ocean, which constitute the majority of the marine environment, mixotrophy provides a critical adaptive advantage that enables microbial communities to overcome limitations of both inorganic nutrients and organic carbon [17]. This metabolic flexibility is particularly relevant in the context of global ocean warming and increased stratification, which are expected to further expand nutrient-limited regions. The ecological significance of mixotrophy extends from cellular physiology to global biogeochemical cycles, influencing carbon export, trophic transfer efficiency, and nutrient regeneration [18] [19].

Within this framework, the phylum Marinisomatota (formerly known as Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, and SAR406) exemplifies how metabolic versatility enables colonization of diverse marine habitats. Traditionally characterized as heterotrophic microorganisms, recent evidence reveals that certain Marinisomatota lineages possess genetic capabilities for light-dependent metabolic processes, blurring the boundaries between nutritional modes [2] [20]. This physiological plasticity allows them to thrive in the transitional zones between sunlit and dark ocean layers, where resources are often patchy and unpredictable. The study of Marinisomatota thus provides a model system for understanding the evolutionary drivers and ecological consequences of mixotrophy in the world's oceans.

Theoretical Foundations: Why Mixotrophy Succeeds in Nutrient-Limited Systems

Resource Colimitation and Metabolic Synergy

The ecological success of mixotrophic organisms in nutrient-limited systems can be attributed to their ability to simultaneously address multiple resource constraints that would limit specialists. In the classic paradigm of marine ecology, autotrophic phytoplankton are limited by inorganic nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, iron), while heterotrophic zooplankton are constrained by carbon-based energy derived from prey [17]. Mixotrophs overcome these parallel limitations through synergistic integration of both nutritional pathways.

Table 1: Comparative Limitations of Different Trophic Strategies in Oligotrophic Oceans

| Trophic Strategy | Primary Limitation | Metabolic Constraint | Competitive Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Autotrophy | Inorganic nutrients | Inability to access nutrient reserves in prey | Outcompeted for nutrients by smaller, more efficient cells |

| Strict Heterotrophy | Organic carbon/energy | Respiratory carbon losses | Prey quantity and quality limitations |

| Mixotrophy | Balanced supply of multiple resources | Metabolic maintenance costs | Advantageous under dual nutrient and carbon limitation |

Theoretical models demonstrate that mixotrophy is particularly favored when the entire microbial community is colimited by both nutrients and carbon, rather than by nutrients alone [17]. In such scenarios, the benefits of combining trophic strategies become greater than the sum of their parts. Phototrophy helps mixotrophs compensate for respiratory carbon losses experienced by strict heterotrophs, while phagotrophy or osmotrophy provides access to nutrient pools that are unavailable to strict phototrophs. This synergistic advantage allows mixotrophs to thrive in the stratified oligotrophic gyres, where an extremely limited supply of nutrients to the euphotic zone is rapidly sequestered by highly competitive bacterioplankton [17] [21].

Ecological Advantages Across Environmental Gradients

Empirical data reveal that mixotrophic nanoflagellates achieve their highest relative abundances in two contrasting marine environments: the brightly lit but nutrient-impoverished subtropical oceans and the more productive waters of coastal regions [17]. This bimodal distribution reflects the flexible ecological advantages of mixotrophy across different resource regimes. In oligotrophic waters, mixotrophs dominate because they can access nutrient reserves contained in bacterial prey while maintaining photosynthetic capability. In more productive coastal systems, where dissolved nutrients are more abundant relative to prey, mixotrophs gain an advantage over specialist heterotrophs through their ability to supplement their nutrition with photosynthesis [21].

Global ecosystem models that incorporate mixotrophy predict significant impacts on marine food webs and biogeochemical cycles. Compared to models with strict trophic separation, mixotrophic simulations show an approximately threefold increase in global mean organism size and a ∼35% increase in sinking carbon flux [18]. This occurs because mixotrophy enhances trophic transfer efficiency, allowing more energy and biomass to reach larger size classes further up the food chain. The resulting shift toward larger plankton communities increases the production of larger, faster-sinking, and carbon-enriched organic detritus, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the biological carbon pump [18] [19].

Marinisomatota: A Model for Understanding Mixotrophic Adaptations

Genomic and Metabolic Diversity

Recent comprehensive analysis of Marinisomatota has revealed extraordinary diversity within this phylum, with 1,588 metagenome-assembled genomes representing 1 class, 2 orders, 14 families, 31 genera, and 67 species [2] [20]. These organisms are predominantly found in low-latitude marine regions, with relative abundances ranging from 0.18% to 36.21% of microbial communities, highlighting their ecological significance in tropical and subtropical oceans where nutrient limitation is most severe [2].

Detailed genomic analysis has identified three distinct metabolic strategies within the Marinisomatota phylum:

MS0 (Photoautotrophic Potential): These lineages possess genetic capabilities for light-dependent processes associated with Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169), potentially enabling them to fix carbon dioxide and synthesize organic compounds using light energy [2] [20]. This strategy was particularly identified in the families S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, and UBA8226.

MS1 (Heterotrophic with Pronounced Glycolytic Pathway): These heterotrophic Marinisomatota maintain an active glycolytic pathway for carbon processing, suggesting adaptation to environments with higher availability of dissolved organic matter.

MS2 (Heterotrophic without Glycolysis): These strictly heterotrophic lineages lack significant glycolytic capability, potentially relying on alternative carbon processing pathways or specialized substrate utilization.

Table 2: Metabolic Strategies Identified in Marinisomatota and Their Environmental Distribution

| Metabolic Strategy | Trophic Mode | Key Genetic Features | Environmental Preference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS0 | Mixotrophic (Photoautotrophic potential) | Genes for Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169) | Transition zones between translucent and aphotic layers |

| MS1 | Heterotrophic | Pronounced glycolytic pathway | Environments with higher dissolved organic carbon |

| MS2 | Heterotrophic | Limited glycolytic capability | Specialized niches with specific organic substrates |

The emergence of these distinct metabolic strategies likely represents evolutionary adaptations to the patchy and unpredictable distribution of nutrients in the oceanic water column. The presence of phototrophic capabilities in multiple families suggests that light harnessing provides a significant selective advantage in the deep chlorophyll maximum and other dimly lit but nutrient-rich microenvironments [2].

Ecological Distribution and Niche Partitioning

Marinisomatota exhibit a distinctive vertical distribution pattern that reflects their metabolic diversity. They are particularly abundant in the translucent zone or in transition areas between the translucent and aphotic layers, where light is sufficient to drive phototrophic processes but where nutrient concentrations often exceed those in surface waters [2]. This distribution enables them to exploit gradients of both light and nutrient availability, potentially using phototrophic metabolism to supplement heterotrophic nutrition when prey are scarce or of poor quality.

The coexistence of multiple Marinisomatota lineages with different metabolic strategies suggests extensive niche partitioning within this phylum. The mosaic distribution of resources in the water column, including spatial and temporal variation in light intensity, dissolved organic matter quality and quantity, and prey availability, likely supports this metabolic diversity by creating multiple distinct niches [2]. This ecological specialization may enhance the overall resilience of Marinisomatota communities to environmental variability and change, as different lineages are optimized for different conditions.

Methodologies for Studying Mixotrophy in Marine Microbes

Genomic and Transcriptomic Approaches

Cutting-edge research on mixotrophic microorganisms relies on integrated multi-omics approaches that combine metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and sometimes metaproteomic methodologies. The recent study of Marinisomatota involved analysis of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data sourced from global open oceans [2] [20], following a comprehensive workflow:

Figure 1: Integrated multi-omics workflow for studying mixotrophic microbes. Gold nodes highlight sequencing steps critical for genomic and transcriptomic analysis.

This methodology enables researchers to not only identify the metabolic potential encoded in microbial genomes but also to understand which metabolic pathways are actively expressed under different environmental conditions. For Marinisomatota, this approach revealed that the genetic capacity for light-dependent metabolism was actually transcribed in specific lineages, providing stronger evidence for mixotrophic capabilities [2].

Stable Isotope and Physiological Methods

Complementary to omics approaches, stable isotope techniques provide critical insights into the relative contributions of autotrophic and heterotrophic nutrition to mixotroph growth and metabolism. A study on coral symbionts (which function as mixotrophic associations) employed carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis to quantify nutritional sources [22]. The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Sample Collection: Field collection of target organisms and potential nutritional sources (e.g., plankton, particulate organic matter).

- Isotopic Enrichment: In some cases, incubation with

^13C-bicarbonate (to track carbon fixation) or^15N-labeled compounds (to track nitrogen uptake). - Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry: Precise measurement of isotopic composition in sample tissues.

- Bayesian Mixing Models: Statistical analysis to determine the proportional contributions of different nutritional sources.

This methodology revealed that corals with different symbiotic algae (Cladocopium vs. Durusdinium) exhibited distinct trophic strategies and nutritional plasticity, with seasonal shifts in the relative dependence on autotrophy versus heterotrophy [22]. Similar approaches could be applied to free-living mixotrophic microbes like Marinisomatota to quantify their actual reliance on phototrophic versus heterotrophic nutrition across environmental gradients.

Research Reagent Solutions for Mixotrophy Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Investigating Microbial Mixotrophy

| Reagent/Methodology | Application | Specific Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | Genome-resolved metagenomics | Recovering metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) | Reconstruction of 1,588 Marinisomatota genomes from global ocean samples [2] |

| Metatranscriptomic Library Prep | Gene expression analysis | Profiling actively transcribed metabolic genes | Identifying expressed Crassulacean acid metabolism pathways in Marinisomatota [2] [20] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (^13C, ^15N) | Trophic pathway tracing | Quantifying elemental fluxes from specific sources | Tracking nutrient transfer in Synechococcus-heterotroph co-cultures [23] |

| qPCR Reagents | Absolute quantification | Measuring abundance of specific taxonomic groups | Quantifying PdC vs. PdD coral symbiont abundances [22] |

| CHEMSTAT Continuous Cultivation | Nutrient limitation studies | Maintaining steady-state nutrient conditions | Investigating phosphorus limitation effects on Crocosphaera [24] |

Ecological Implications and Global Significance

Impacts on Carbon Export and Nutrient Cycling

The widespread distribution of mixotrophic organisms like Marinisomatota has profound implications for global biogeochemical cycles. Model simulations indicate that mixotrophy enhances the transfer of biomass to larger size classes further up the food chain, leading to significant increases in mean organism size and sinking carbon flux [18]. This occurs because mixotrophs can maintain higher growth efficiencies than strict heterotrophs by using photosynthesis to supplement their energy needs, reducing respiratory carbon losses. The resulting shift toward larger plankton communities enhances carbon export efficiency, as larger particles sink more rapidly and are less susceptible to remineralization in surface waters [18] [19].

In addition to impacts on the biological carbon pump, mixotrophy influences the cycling of limiting nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron. By accessing nutrient pools contained in bacterial prey, mixotrophs can short-circuit the conventional nutrient regeneration pathways that involve multiple trophic transfers. This more direct nutrient recycling pathway potentially enhances nutrient use efficiency in oligotrophic ecosystems, allowing primary production to be maintained despite severely limited external nutrient inputs [17] [19]. The presence of nitrogen fixation capabilities in some heterotrophic bacteria associated with photosynthetic microbes [23] further illustrates how mixotrophic associations can influence nutrient cycling in the ocean.

Responses to Environmental Change

Mixotrophic organisms may be particularly well-positioned to respond to ongoing environmental changes such as ocean warming, acidification, and deoxygenation. Their trophic flexibility provides a buffer against environmental variability that specialists lack, potentially enhancing ecosystem resilience to disturbance. However, the responses are likely to be complex and taxon-specific. Research on single-celled nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (Crocosphaera) has demonstrated that the effects of ocean acidification are modulated by iron and phosphorus limitation [24], with negative impacts exacerbated under iron-limited conditions but attenuated under phosphorus limitation.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of mixotrophic responses to environmental change. Gold nodes highlight key adaptive strategies, while red indicates potential physiological impacts.

The diverse metabolic strategies observed in Marinisomatota [2] suggest that different lineages will show varying responses to environmental change. Those with more flexible metabolic capabilities (e.g., MS0-type strategies) may be better able to acclimate to changing conditions than those with more specialized metabolisms (e.g., MS2-type strategies). This intraphylum diversity could enhance the resilience of Marinisomatota as a group to environmental changes, as different lineages are likely to respond differently, ensuring that some representatives persist under virtually all future scenarios.

The study of mixotrophy in nutrient-limited oceans has evolved from documenting curiosities that defy simple classification to recognizing a fundamental ecological strategy that shapes marine ecosystem structure and function. Marinisomatota, with their diverse metabolic strategies and widespread distribution, exemplify how trophic flexibility enables colonization of the vast oligotrophic regions of the ocean. Their genomic capacity for both phototrophic and heterotrophic metabolism represents an adaptive solution to the dual challenges of carbon and nutrient limitation that characterize these environments.

Future research on mixotrophy should focus on quantifying the in situ metabolic activity of different mixotrophic strategies across environmental gradients, understanding the evolutionary drivers of mixotrophy in diverse lineages, and incorporating realistic representations of mixotrophy into global biogeochemical models. As ocean habitats continue to change under human pressure, understanding the ecological role of mixotrophic organisms will be essential for predicting the future of marine ecosystems and their capacity to sustain critical ecosystem services including carbon sequestration and fisheries production.

Marinisomatota (formerly known as Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, and SAR406) represents a phylogenetically diverse and metabolically versatile phylum that is ubiquitous and abundant in global ocean ecosystems. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes recent metagenomic and metatranscriptomic findings which have identified a comprehensive taxonomic framework for this phylum, encompassing 1,588 genomes representing 14 families and 67 species [2]. We detail the experimental protocols enabling these discoveries and present quantitative analyses of their ecological distribution, with relative abundances ranging from 0.18% to 36.21% across low-latitude marine regions [2]. The functional diversity of Marinisomatota is exemplified by three distinct metabolic strategies—photoautotrophic potential (MS0), heterotrophic with enhanced glycolytic capacity (MS1), and heterotrophic without glycolysis (MS2)—which represent adaptations to nutrient limitations in oceanic ecosystems [8] [2]. This systematic classification and functional characterization provides researchers with a foundational framework for exploring the biotechnological potential of this ecologically significant bacterial phylum.

Marinisomatota represents one of the most widespread yet enigmatic bacterial phyla in marine environments, traditionally characterized as heterotrophic microorganisms with limited cultivability. Recent advances in genome-resolved metagenomics have dramatically expanded our understanding of their phylogenetic diversity and ecological significance. The current taxonomic framework, derived from analysis of global ocean metagenomic datasets, positions Marinisomatota within a structured hierarchy comprising one class, two orders, 14 families, 31 genera, and 67 species [2]. This classification system provides researchers with a standardized nomenclature for comparing functional traits across phylogenetic boundaries and investigating evolutionary relationships within this metabolically versatile phylum.

The ecological distribution of Marinisomatota exhibits distinct biogeographic patterns, with predominance in low-latitude marine regions where they can achieve remarkable relative abundances ranging from 0.18% to 36.21% of microbial communities [2]. Among the 14 identified families, five—S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, and UBA8226—demonstrate particular ecological success and possess genetic potential for light-dependent processes associated with Crassulacean acid metabolism (M00169) [2]. This strategic distribution across oceanic provinces suggests specialized niche adaptation driven by both phylogenetic history and environmental parameters, positioning Marinisomatota as significant contributors to marine biogeochemical cycling.

Methodological Approaches for Marinisomatota Research

Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Workflow

The reconstruction of Marinisomatota genomes from complex environmental samples requires sophisticated metagenomic approaches that overcome the limitations of traditional cultivation techniques. The following workflow outlines the primary methodology used to establish the current phylogenetic framework encompassing 14 families and 67 species:

Table 1: Metagenomic Assembly and Binning Parameters for Marinisomatota Genome Reconstruction

| Processing Step | Tools/Platforms | Key Parameters | Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Assembly | MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes | k-mer sizes: 21-121; min contig length: 1000 bp | N50 > 10 kbp; complete single-copy genes |

| Genome Binning | MetaBAT2, MaxBin2, CONCOCT | minimum bin completeness: >50%; maximum contamination: <10% | CheckM completeness >70%; contamination <5% |

| Taxonomic Classification | GTDB-Tk, CheckM | reference database: GTDB r89; phylogenetic markers: 120+ bacterial proteins | ANI <95% for species distinction; AAI for genus assignment |

| Functional Annotation | PROKKA, EggNOG | COG categories; KEGG pathways; Pfam domains | >70% coding density; tRNA genes for all amino acids |

The integrated workflow begins with quality filtering of raw metagenomic reads followed by co-assembly of multiple samples to enhance recovery of low-abundance populations. Subsequent binning strategies employ complementary algorithms to maximize genome completeness while minimizing contamination, with particular attention to distinguishing Marinisomatota from phylogenetically similar groups. The taxonomic classification leverages the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) framework, which provides standardized taxonomic ranks based on relative evolutionary divergence rather than phenotypic traits, ensuring consistent phylogenetic placement across studies [10]. This approach has enabled the reconstruction of 1,588 Marinisomatota genomes from global ocean datasets, forming the foundation for the current phylogenetic framework of 14 families and 67 species [2].

Metabolic Reconstruction and Functional Prediction

Functional characterization of Marinisomatota employs complementary omics approaches to elucidate the metabolic potential encoded within their genomes. Metabolic pathways are reconstructed through integrated annotation pipelines that identify key enzymes and transport systems within each genome:

Pathway Identification: The presence of complete metabolic pathways is determined through hidden Markov model searches against curated profile databases (KEGG, MetaCyc) with manual validation of key catalytic steps.

Gene Cluster Analysis: Biosynthetic gene clusters are identified using antiSMASH with strict cutoff thresholds (E-value <1e-10, coverage >60%) to minimize false positives in secondary metabolite prediction.

Transport Capability Assessment: Transporter profiling employs the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) with additional validation through identification of adjacent substrate-binding proteins and energy-coupling mechanisms.

Metatranscriptomic analysis complements these genomic predictions by quantifying expression levels of key metabolic genes across environmental gradients. RNA extraction from environmental samples requires specialized stabilization protocols (RNAlater or immediate flash-freezing at -80°C) to preserve labile transcripts from low-biomass environments. Library preparation typically employs ribosomal RNA depletion followed by strand-specific sequencing to enable differentiation of sense and antisense transcription. The integration of genomic potential with transcriptional activity provides a comprehensive framework for elucidating the functional diversity of Marinisomatota across its phylogenetic spectrum.

Quantitative Analysis of Marinisomatota Diversity

Comprehensive analysis of global metagenomic datasets has enabled systematic quantification of Marinisomatota phylogenetic diversity and distribution patterns. The taxonomic richness across different hierarchical levels reveals a phylum with substantial diversification, particularly at the family and species levels:

Table 2: Taxonomic Diversity of Marinisomatota Across Phylogenetic Ranks

| Taxonomic Rank | Number of Taxa | Genomic Representatives | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | 1 | 1,588 genomes | Formerly Marinimicrobia, Marine Group A, SAR406 |

| Class | 1 | 1,588 genomes | Unified classification based on GTDB |

| Order | 2 | Distribution varies by order | Distinct ecological preferences observed |

| Family | 14 | 5 families with photoautotrophic potential | S15-B10, TCS55, UBA1611, UBA2128, UBA8226 |

| Genus | 31 | Varying from 1 to >100 genomes per genus | Different metabolic strategies by genus |

| Species | 67 | Defined by <95% ANI | Specialization to specific oceanic provinces |

The ecological distribution of Marinisomatota reveals distinct biogeographic patterns influenced by both environmental factors and phylogenetic history. Abundance profiles across global sampling sites demonstrate:

Latitudinal Gradient: Highest relative abundances occur in low-latitude regions (0.18-36.21%), with pronounced dominance in oligotrophic gyres where they can constitute over one-third of microbial communities [2].

Depth Stratification: Distinct phylogenetic lineages partition between epipelagic, mesopelagic, and bathypelagic zones, with specific families exhibiting adaptations to light regimes (e.g., epipelagic families with phototrophic potential) [2] [25].

Provincial Endemism: Despite their global distribution, certain species show restricted distributions aligned with specific water masses, suggesting limited dispersal or specialized adaptation to particular physicochemical conditions [4].

The functional profiling of Marinisomatota genomes reveals substantial conservation of metabolic traits within phylogenetic groups, with an average of 41.4% of variation in Clusters of Orthologous Groups functional categories (COG-FCs) explained by taxonomic rank [10]. This phylogenetic signal in functional capacity demonstrates the interplay between evolutionary history and metabolic specialization in shaping the ecological roles of distinct Marinisomatota lineages.

Metabolic Strategies and Functional Diversity

Marinisomatota exhibits remarkable metabolic versatility, employing distinct strategies to overcome nutrient limitations in oceanic ecosystems. Genomic analysis has identified three primary metabolic modes within the phylum:

MS0 (Photoautotrophic Potential): These lineages possess proteorhodopsin-based light-harvesting systems and potential for Crassulacean acid metabolism, enabling them to harness light energy for carbon fixation in the photic zone [2].

MS1 (Heterotrophic with Enhanced Glycolytic Capacity): Characterized by complete glycolytic pathways and specialized substrate acquisition systems, these organisms excel at processing complex organic matter in mesopelagic regions [2].

MS2 (Heterotrophic without Glycolysis): Lacking complete glycolytic pathways, these lineages rely on alternative carbon processing mechanisms and are often dominant in deep ocean habitats where labile organic matter is scarce [2].

The distribution of these metabolic strategies across the Marinisomatota phylogeny demonstrates a clear evolutionary adaptation to oceanic nutrient gradients. The emergence of mixotrophic capabilities in specific lineages represents a strategic response to the fluctuating resource availability characteristic of marine environments, particularly in oligotrophic regions where light and organic carbon sources may be seasonally variable.

Figure 1: Evolutionary adaptation of Marinisomatota metabolic strategies in response to environmental factors, leading to three distinct metabolic modes (MS0, MS1, MS2) as specialized adaptations to nutrient limitations in oceanic ecosystems [2].

The functional coupling between metabolic potential and environmental distribution is mediated by specialized genetic adaptations. Genomic analyses have identified key enzyme systems that differentiate the metabolic strategies:

MS0 Lineages: Encode proteorhodopsin complexes, carbon concentration mechanisms, and Crassulacean acid metabolism enzymes that facilitate light-driven energy generation and carbon fixation [2].

MS1 Lineages: Possess complete glycolytic pathways (pfk, pyk genes), diverse TonB-dependent transporters for substrate acquisition, and extracellular enzymes for complex organic matter degradation [8] [2].

MS2 Lineages: Feature alternative energy conservation systems including partial glycolysis, specialized fermentative capabilities, and expanded repertoires of oxidoreductases for utilizing recalcitrant organic compounds [2].

This metabolic diversification enables Marinisomatota to occupy distinct ecological niches across the water column, with different phylogenetic lineages dominating specific depth zones and oceanic provinces according to their specialized capabilities.

Research Reagent Solutions for Marinisomatota Studies

Investigating the phylogenetic and functional diversity of Marinisomatota requires specialized research reagents and methodologies optimized for studying uncultivated microbial lineages. The following table details essential solutions for experimental work in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Marinisomatota Studies

| Reagent/Methodology | Specific Application | Function in Research | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Nutrient Media | Cultivation attempts | Mimics oligotrophic marine conditions | Modified SWM, AMC media with 1-10 mg/L organic carbon [8] |

| Diffusion Chambers | In situ cultivation | Allows nutrient exchange with natural environment | Ahmad et al. method for uncultured bacteria [8] |

| Metagenomic Kits | DNA extraction from filters | High-yield, high-molecular-weight DNA | PowerWater DNA Isolation Kit; 0.1-0.2 µm filters |

| Single-Cell Genomics | Genome amplification | Bypasses cultivation requirements | Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) with phi29 polymerase |

| GTDB Database | Taxonomic classification | Standardized phylogenetic framework | GTDB-Tk with r214 reference data [10] [4] |

| antiSMASH | BGC prediction | Identifies secondary metabolite potential | antiSMASH 7.0 with strict cutoff settings [26] |

| COG Databases | Functional annotation | Metabolic pathway reconstruction | eggNOG-mapper with COG categories [10] |

The application of these specialized reagents and methodologies has been instrumental in overcoming the historical challenges associated with studying Marinisomatota. Particularly critical are the low-nutrient cultivation approaches that simulate the oligotrophic conditions of their native habitats, enabling limited success in laboratory isolation of previously uncultured representatives [8]. For the majority of lineages that remain recalcitrant to cultivation, single-cell genomics and metagenome-assembled genomes provide alternative paths to genomic characterization without the need for laboratory growth.

Bioinformatic resources form another essential component of the Marinisomatota research toolkit, with standardized databases and analysis pipelines enabling consistent phylogenetic placement and functional prediction across studies. The Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) provides a phylogenetically consistent framework for taxonomic classification, while functional databases like COG and KEGG enable comparative analysis of metabolic potential across the phylogenetic diversity of the phylum [10] [4]. The integration of these wet-lab and computational approaches has been essential for reconstructing the comprehensive phylogenetic framework of 14 families and 67 species that defines our current understanding of Marinisomatota diversity.

Implications for Ocean Ecosystem Research

The phylogenetic and functional characterization of Marinisomatota has profound implications for understanding marine microbial ecology and biogeochemical cycling. As abundant members of ocean microbial communities, reaching up to 36.21% relative abundance in specific provinces, these organisms significantly influence carbon and energy fluxes through marine ecosystems [2]. Their metabolic versatility enables them to participate in multiple trophic levels, serving as both primary producers through light-driven metabolism and as consumers of organic matter across diverse oceanic provinces.

The distinct biogeographic distribution of Marinisomatota lineages aligns with specific oceanographic features, suggesting their potential as biological indicators of water mass history and ecosystem status. The prevalence of specific families in low-latitude regions and their stratification across depth gradients reflects adaptive responses to physical and chemical parameters that structure microbial communities globally [4] [2]. This phylogenetic patterning provides a framework for predicting microbial community responses to environmental change, particularly in the context of expanding oligotrophic regions due to global warming.

Furthermore, the recently revealed metabolic capabilities of Marinisomatota reshape our understanding of carbon cycling in the deep ocean. The discovery of mixotrophic strategies challenges traditional dichotomies between autotrophic and heterotrophic metabolism in marine systems, revealing a more complex continuum of metabolic functions [2] [25]. This functional diversity enables Marinisomatota to occupy transitional zones between well-lit surface waters and dark ocean depths, potentially facilitating energy transfer across traditional biome boundaries and influencing the efficiency of the biological carbon pump.

The comprehensive phylogenetic framework presented herein—spanning 14 families and 67 species—establishes Marinisomatota as a phylogenetically diverse and metabolically versatile phylum with significant roles in marine ecosystems. The integration of genomic, metatranscriptomic, and ecological data reveals a phylum characterized by specialized adaptations to oceanic nutrient gradients, with distinct metabolic strategies emerging as evolutionary innovations to overcome resource limitation. This systematic classification provides an essential foundation for future investigations aiming to elucidate the precise biogeochemical contributions of specific Marinisomatota lineages and their responses to environmental change. The methodological advances detailed in this guide will enable researchers to further explore the functional significance of this diverse phylum, potentially unlocking novel biotechnological applications and enhancing predictive models of ocean ecosystem functioning in a changing global climate.

From Uncultured to Understood: Advanced Genomic and Cultivation Techniques for Marinisomatota Research

Leveraging Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics from Global Ocean Datasets

The exploration of ocean microbial life has been revolutionized by the advent of genomic technologies. Metagenomics (the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples) and metatranscriptomics (which analyzes the expressed RNA within those samples) have transformed our understanding of marine ecosystems by bypassing the limitations of traditional culturing methods [27] [28]. These approaches provide an unprecedented window into the taxonomic composition and functional capabilities of marine microbial communities, enabling researchers to decipher their roles in global biogeochemical cycles, adaptive strategies, and biotechnological potential.

The global ocean represents the planet's largest ecosystem, hosting an estimated 10²⹠bacterial and archaeal cells that underpin essential ecological processes and biogeochemical fluxes [4]. Landmark projects such as the Global Ocean Sampling expedition and the Tara Oceans Expedition have dramatically expanded our inventory of oceanic microbial diversity, leading to massive genomic datasets that capture variations across latitude, depth, and environmental gradients [4]. These initiatives have illuminated the stunning diversity of marine microbes while simultaneously creating new opportunities for discovering novel enzymes, antimicrobial compounds, and metabolic pathways with biomedical and industrial relevance.

This technical guide examines current methodologies, analytical frameworks, and applications of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics in marine microbial research, with particular emphasis on the functional diversity of understudied phyla such as Marinisomatota. We provide a comprehensive resource for researchers seeking to leverage global ocean datasets to advance understanding of microbial ecology, evolution, and bioprospecting.