Unveiling the Hidden Realm: Cryptic Biodiversity in Marine Hotspots and Its Promise for Biomedical Discovery

Marine biodiversity hotspots, regions of exceptional species richness and endemism, harbor a vast and largely unexplored reservoir of cryptic diversity—species that are morphologically similar but genetically distinct.

Unveiling the Hidden Realm: Cryptic Biodiversity in Marine Hotspots and Its Promise for Biomedical Discovery

Abstract

Marine biodiversity hotspots, regions of exceptional species richness and endemism, harbor a vast and largely unexplored reservoir of cryptic diversity—species that are morphologically similar but genetically distinct. This article explores the foundational concepts of these hotspots and their cryptic components, reviews advanced methodological tools like eDNA metabarcoding and ARMS for detection, addresses key challenges in bioprospecting and species identification, and validates findings through comparative genomic and ecological analyses. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how uncovering this hidden diversity is critical for discovering novel marine natural products with unique mechanisms of action against human diseases, ultimately bridging the gap between ecological discovery and clinical application.

The Unseen World: Defining Marine Hotspots and Cryptic Biodiversity

What Are Marine Biodiversity Hotspots? Defining Characteristics and Global Significance

Marine biodiversity hotspots are geographic regions in the ocean characterized by an exceptionally high concentration of marine species, many of which are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else on Earth [1] [2]. These regions are not only vital reservoirs of marine genetic diversity but also face severe threats from human activities, making them among the highest priorities for global conservation efforts [1]. The scientific study of these hotspots has evolved from simply cataloging species richness to understanding complex biogeographic patterns, evolutionary histories, and the ecological functions that sustain this diversity.

This technical guide frames marine biodiversity hotspots within the context of cryptic biodiversity research—the study of species that are morphologically similar but genetically distinct. Advances in molecular techniques are revolutionizing our understanding of these regions, revealing a hidden layer of diversity that was previously undetectable, with profound implications for conservation science and bioprospecting [3] [4].

Defining Characteristics and Global Distribution

The formal designation of a biodiversity hotspot relies on specific, quantifiable criteria. These regions are identified based on two primary factors: exceptional endemism and significant habitat loss [2]. To qualify, a region must contain a high number of endemic species and have lost a substantial portion of its primary habitat, typically set at a threshold of 70% or more [2].

The global distribution of marine biodiversity is not uniform. The most prominent hotspot is the Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA), also known as the Coral Triangle, which is recognized as the world's preeminent marine biodiversity hotspot [3] [5]. This region exhibits a distinctive "bull's-eye" pattern of species richness, with diversity declining latitudinally toward the poles and longitudinally toward the eastern Pacific and western Indian Oceans [3]. Secondary hotspots include the Caribbean Sea and the Mesoamerican Reef region [1] [3].

Table 1: Major Marine Biodiversity Hotspots and Their Characteristics

| Hotspot Name | Key Geographic Areas | Notable Species & Habitats | Threat Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA)/Coral Triangle | Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea [3] | >650 Ostracod species; corals, reef fishes [5] | Habitat degradation, climate change [3] |

| Mesoamerican Marine Hotspot | Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico), Belize, Guatemala, Honduras [1] | Mesoamerican Barrier Reef (4,000+ species), mangroves, seagrass beds [1] | Habitat loss, overfishing [1] |

| Caribbean | Caribbean Sea [3] | Coral reefs, mangroves (50% plant endemism) [1] [3] | Historical mass extinction, current threats [5] |

The table above summarizes key characteristics of major marine biodiversity hotspots. The IAA's status is supported by a high-resolution reconstruction of its Cenozoic diversity history, which shows a unidirectional diversification trend since about 25 million years ago, culminating in a diversity plateau beginning about 2.6 million years ago [5]. The Mesoamerican hotspot is notable for the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second-largest barrier reef in the world, which shelters over 4,000 species, including whale sharks, sea turtles, and manta rays [1].

Evolutionary Origins and Biogeographic Theories

The formation of major biodiversity hotspots is a product of long-term evolutionary and geological processes. Two prominent theoretical frameworks dominate explanations for the origins of the IAA's exceptional biodiversity [3].

The "centers-of" hypotheses propose that specific regions serve as key sources of biodiversity through various mechanisms. The center of origin hypothesis suggests high biodiversity stems from elevated rates of local speciation followed by outward dispersal. In contrast, the center of accumulation posits that diversity results from preferential colonization by species originating elsewhere. The center of overlap hypothesis describes regions where distinct biogeographic faunas converge, while the center of survival identifies areas that have acted as refugia with low extinction rates [3].

In contrast, the "hopping hotspot" hypothesis presents a dynamic view, suggesting that biodiversity hotspots have shifted geographically over geological timescales in response to tectonic and environmental changes [3]. Evidence suggests a westward origin in the Tethys Sea during the Eocene (42-39 million years ago), a subsequent shift to the Arabian region by the late Miocene (around 20 million years ago), and a final relocation to the IAA by the Pleistocene (approximately 1 million years ago) [3]. This migration is linked to major geological events, particularly the closure of the Tethys Sea and the collision between the Australian and Southeast Asian tectonic plates, which dramatically altered ocean currents and created new shallow marine environments [3].

A more recent synthesis, the "Dynamic Centers Hypothesis," integrates these perspectives, proposing that as biodiversity hotspots migrate over time, the IAA's role in generating and sustaining biodiversity has evolved, with varying contributions from different sources dominating distinct historical phases [3]. Fossil evidence from ostracods indicates that the IAA's diversification was primarily controlled by diversity dependency and habitat size, facilitated by the alleviation of thermal stress after 13.9 million years ago [5]. Distinct net diversification peaks at approximately 25, 20, 16, 12, and 5 million years ago appear related to major tectonic events and climate transitions [5].

Cryptic Diversity and Modern Research Methodologies

The Challenge of Cryptic Biodiversity

A critical frontier in marine biodiversity research involves the discovery and characterization of cryptic species—genetically distinct lineages that are morphologically similar or identical. This hidden diversity presents significant challenges for traditional taxonomy and conservation planning, as what appears to be a single widespread species may actually represent multiple evolutionarily distinct units with smaller ranges and different ecological requirements [3]. Advances in DNA barcoding and genomics are uncovering vast cryptic diversity within known hotspots, revolutionizing our comprehension of their phylogeographic history and true species richness [3].

Experimental Workflow for Hotspot Research

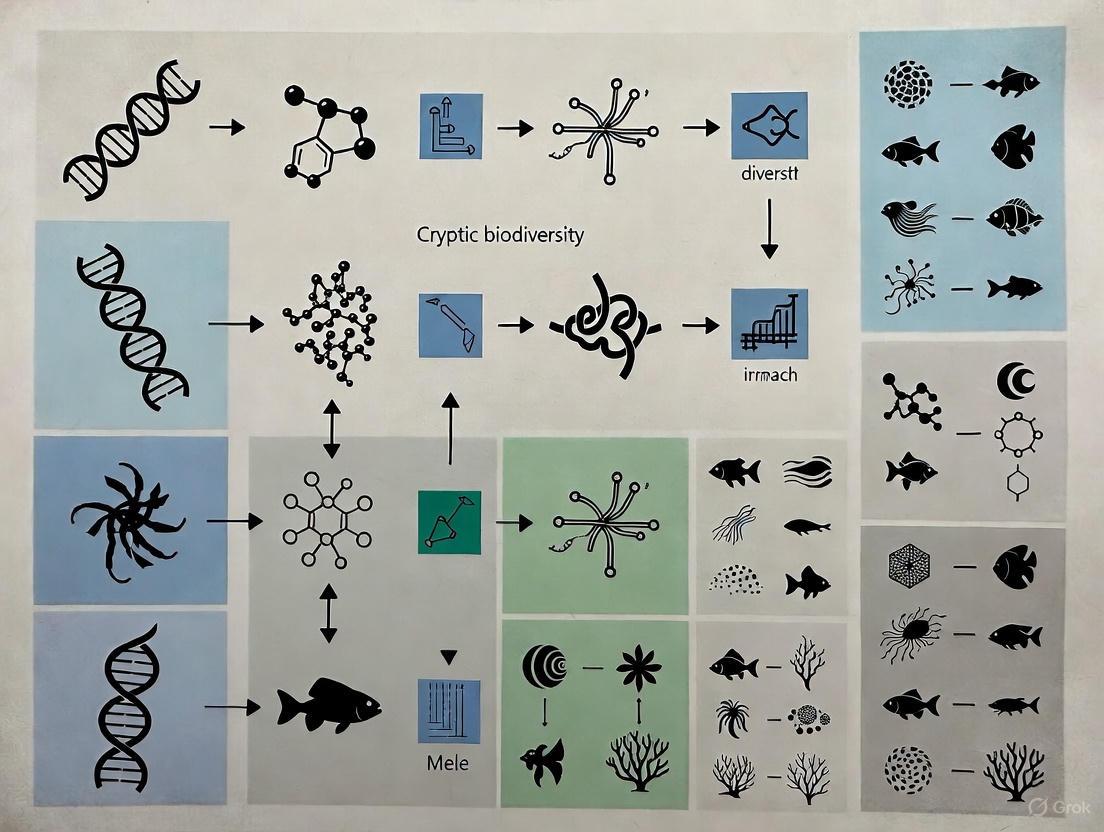

Modern research into marine biodiversity hotspots employs an integrated methodological approach combining traditional ecological surveys with cutting-edge molecular techniques. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for studying biodiversity hotspots, with particular emphasis on detecting cryptic diversity.

Diagram 1: Integrated Research Workflow for Marine Biodiversity Hotspots. This workflow combines traditional morphological surveys with modern eDNA metabarcoding and bioinformatic analyses to comprehensively characterize biodiversity, including cryptic species.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The experimental workflow described above relies on specialized reagents, equipment, and computational tools. The following table details key components of the "research reagent solutions" essential for conducting modern biodiversity hotspot research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Marine Biodiversity Hotspot Studies

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Collection | Niskin bottles, Sterivex-GP cartridge filters (0.45 μm), peristaltic pumps [4] | Sterile collection of water samples for eDNA analysis from multiple depth layers. |

| Genetic Markers | MiFish primers (12S rRNA) [4] | Amplification of specific gene regions for metabarcoding of fish communities. |

| Sequencing & Analysis | NextSeq500/HiSeq X platforms, Qiime2, DADA2 package, BLAST [4] | High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatic processing to identify ASVs/OTUs. |

| Reference Databases | MIDORI2, NCBI GenBank, rfishbase [4] | Reference databases for taxonomic assignment of sequenced DNA barcodes. |

| Data Visualization & Mapping | eDNAmap platform, Generic Mapping Tools, R packages (vegan, pheatmap) [4] | Analysis, visualization, and mapping of species composition and biogeographic boundaries. |

The eDNAmap web platform is particularly noteworthy as a specialized tool for comparing marine metabarcoding data. It allows researchers to upload species or sequence composition data with location information, automatically plot sampling locations, generate heatmaps, perform multivariate statistical analyses (e.g., nMDS, PERMANOVA), and display species distributions [4]. This tool facilitates the detection of concordant biogeographic patterns across different taxonomic groups, strengthening ecological interpretations and helping identify environmental drivers shaping community structures [4].

Global Significance and Conservation Frameworks

Ecological and Biomedical Importance

Marine biodiversity hotspots deliver essential ecosystem services including coastal protection (e.g., by coral reefs and mangroves), carbon sequestration, and support for fisheries that sustain coastal communities [1] [2]. Their rich biological diversity represents a natural library of genetic information with significant potential for drug discovery and biomedical innovation [6].

The preservation of biodiversity is critically linked to pharmaceutical development, as natural products from marine organisms provide unique molecular structures honed by billions of years of evolution [6]. Alarmingly, modern extinction rates are 100 to 1000 times greater than historical background rates, potentially causing the loss of important drug candidates every two years [6]. This irreversible loss of molecular diversity threatens biomedical research and future human health advancements [6].

Threats and Integrated Conservation Strategies

Marine biodiversity hotspots face severe, interconnected threats. Overfishing represents the most significant impact over the past 50 years, with 37.7% of global fish stocks currently overfished and oceanic shark and ray species declining by 71% since the 1970s [7]. Additional major threats include climate change (causing coral bleaching and ocean acidification), pollution from land-based activities, and direct habitat destruction from coastal development and destructive fishing practices [1] [2] [7].

Effective conservation requires moving beyond simple protection to integrated, multidimensional strategies. These include [2]:

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Shark Sanctuaries: Establishing and effectively managing protected areas, such as the national shark sanctuary in Honduras [1].

- Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management (EBFM): Shifting from single-species management to holistic approaches that consider entire ecosystems, including reducing bycatch and protecting spawning grounds [2] [7].

- Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM): Managing human activities in coastal areas through collaboration among governments, industries, and local communities to minimize impacts on marine ecosystems [2].

- Restoration Ecology: Actively restoring degraded habitats through coral reef restoration, mangrove replanting, and seagrass bed rehabilitation [2].

- Innovative Financing: Developing sustainable funding through blue bonds, debt-for-nature swaps, and payments for ecosystem services [2].

A comprehensive update to the world's biodiversity hotspots project began in 2025, aiming to incorporate 25 years of new data from the IUCN Red List and advanced metrics like the STAR (Species Threat Abatement and Restoration) metric to better direct conservation funding and action [8].

Marine biodiversity hotspots are complex bio-socio-ecological systems characterized by exceptional species richness, high endemism, and significant evolutionary novelty, all under severe anthropogenic pressure. Understanding their defining characteristics—from the macroevolutionary processes that shaped them to the cryptic diversity being revealed by molecular tools—is essential for their conservation. The ongoing development of sophisticated research methodologies, including eDNA metabarcoding and integrative bioinformatic platforms, is transforming our ability to document and monitor these vital regions. Protecting these irreplaceable centers of marine life requires a transdisciplinary approach that integrates evolutionary biology, ecology, conservation science, and policy implementation to ensure their persistence and the critical ecosystem services they provide to humanity and the planet.

Cryptic species are groups of organisms that are morphologically indistinguishable from one another but are genetically distinct enough to be considered separate species [9]. These species pose significant challenges for taxonomists and ecologists because traditional methods of species identification, which rely on visible physical traits, fail to distinguish them [9]. The term is often used interchangeably with "sibling species," particularly for closely related species that have recently diverged [10]. In marine systems, where many phyla are less accessible and known primarily from preserved material, cryptic species are increasingly recognized as a substantial component of biodiversity, potentially comprising "tens of thousands" of accepted described species [10].

The study of cryptic species is particularly relevant in marine biodiversity hotspots like French Polynesia, where baseline biodiversity information is often fragmented and incomplete [11]. As molecular tools become more accessible, the discovery of cryptic species complexes is accelerating, fundamentally altering our understanding of species distributions, biogeographic patterns, and conservation priorities in marine environments [12]. This technical guide explores the concepts, methodologies, and implications of cryptic species research within the broader context of marine biodiversity science.

Conceptual Framework and Terminology

Defining Cryptic Species

The "cryptic species" concept has a long history of varied usage, causing ambiguity when interpreting their evolutionary and ecological significance [10]. They are frequently defined as species that are morphologically difficult to diagnose despite being genetically distinct evolutionary lineages [13]. The synonymous term "sibling species" (from the German "geschwisterarten") has historical precedence and implies closely related species that may have recently diverged [10].

Distinguishing Related Terminology

- Cryptic Species: Species that appear identical or nearly identical in morphology but are genetically distinct and reproductively isolated. These are often discovered through molecular techniques rather than traditional morphological examination [9].

- Sibling Species: A type of cryptic species; two or more species that are morphologically similar but genetically distinct. The term implies close evolutionary relationship and potential recent divergence, often with sympatric distributions and subtle ecological or behavioral differences [9].

- Sister Species: The closest relatives on an evolutionary tree, sharing a most recent common ancestor. While sister species can be morphologically distinct or similar, they are defined primarily by phylogenetic relationship rather than appearance [9].

Table 1: Conceptual Terminology in Cryptic Species Research

| Term | Definition | Primary Basis of Distinction | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptic Species | Morphologically indistinguishable but genetically distinct species | Genetic divergence despite morphological similarity | Reveals hidden diversity; may indicate recent divergence or morphological stasis |

| Sibling Species | Closely related cryptic species | Genetic distinctness with high morphological similarity | Suggests recent evolutionary divergence, potentially with ecological differentiation |

| Sister Species | Two species that are closest relatives on a phylogenetic tree | Shared most recent common ancestor | Defined by phylogenetic relationship regardless of morphological distinction |

| Species Complex | Group of closely related species difficult to delineate | Combined morphological, genetic, and ecological data | Represents ongoing speciation or recent divergence events |

Methodological Approaches: Uncovering Hidden Diversity

Molecular Tools for Species Delimitation

DNA Barcoding

DNA barcoding has emerged as a pivotal technique for species identification, relying on sequencing a standardized region of the genome—typically the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene in animals—to produce a unique genetic identifier for each species [9] [14]. These barcodes are compared to comprehensive reference libraries to confirm species identity. The utility of DNA barcoding extends to delineating cryptic species by uncovering genetic disparities between organisms that appear identical [9]. For example, in the butterfly genus Astraptes, what was once thought to be a single species was revealed to be at least ten cryptic species using DNA barcoding [9].

However, marine barcoding initiatives face significant challenges. Current assessments indicate that only 14.2% of known marine animal species had COI barcodes available as of 2021, a modest increase from 9.5% in 2011 [14]. This barcoding coverage varies substantially among phyla (from 4.8% to 74.7%) and geographic regions (from 36.8% to 62.4% across Large Marine Ecosystems), with Porifera, Bryozoa, and Platyhelminthes being highly underrepresented compared to Chordata, Arthropoda, and Mollusca [14].

Metabarcoding and Environmental DNA

Metabarcoding extends the principles of DNA barcoding to analyze entire biological communities from environmental samples such as water or sediment [9]. This method extracts DNA from bulk samples and identifies multiple species simultaneously by comparing sequences to reference databases. Metabarcoding is particularly effective for delineating cryptic species within complex ecosystems where traditional survey methods may miss less conspicuous organisms [9].

Environmental DNA (eDNA) barcoding represents another advancement in non-invasive species detection. By extracting DNA directly from environmental matrices, eDNA barcoding captures genetic signatures without direct observation or specimen collection [9]. This technique is invaluable for monitoring elusive or rare cryptic species and has proven especially powerful in aquatic environments [9].

Phylogenetic Haplotype Network Analysis

For cryptic species complexes where recent divergence may involve ongoing or attenuated gene flow, phylogenetic networks offer advantages over traditional phylogenetic trees. Networks better visualize relationships when clear barcoding gaps don't exist and gene flow may still persist between sister lineages [13].

The statistical parsimony algorithm implemented in TCS network software can be used to construct phylogenetic haplotype networks from global metabarcoding datasets [13]. This approach was successfully applied to the Chaetoceros curvisetus (Bacillariophyta) species complex, using data from global initiatives like Ocean Sampling Day (OSD) and Tara Oceans [13]. The methodology involves:

- Reference Sequence Collection: Gathering reference sequences of target genes from cultured strains or databases.

- Metabarcode Data Processing: Downloading and processing metabarcoding datasets, extracting unique haplotypes and abundance tables.

- Haplotype Validation: Using BLAST searches with relaxed similarity thresholds (e.g., ≥95%) to extract haplotypes belonging to the target complex, followed by phylogenetic tree construction to remove false positives.

- Network Construction: Building phylogenetic haplotype networks using statistical parsimony and visualizing them with tools like PopART, including read abundance information for each haplotype.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Cryptic Species Delimitation. This diagram outlines the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for identifying cryptic species from environmental samples, combining metabarcoding with phylogenetic network analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Cryptic Species Research

| Item/Category | Specification/Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits for environmental samples | Isolation of high-quality DNA from diverse marine samples including water, sediment, and tissue |

| PCR Reagents | Primers for barcode regions (COI, 18S V4/V9, ITS) | Amplification of standardized genetic markers for species identification and delimitation |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore technologies | High-throughput generation of genetic sequence data from single specimens or mixed samples |

| Reference Databases | BOLD, NCBI, WoRMS, OBIS | Taxonomic validation and comparison of unknown sequences against known references |

| Bioinformatic Tools | mothur, QIIME2, POPART, TCS | Processing raw sequence data, constructing haplotype networks, and visualizing phylogenetic relationships |

| Taxonomic Validators | WoRMS, GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, Taxize R package | Standardizing and verifying taxonomic nomenclature across disparate data sources |

| Environmental Samplers | Niskin bottles, sediment corers, plankton nets | Collection of representative samples from various marine habitats and depth strata |

| N-Boc-piperazine | N-Boc-piperazine, CAS:57260-71-6, MF:C9H18N2O2, MW:186.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thiomuscimol | Thiomuscimol|CAS 62020-54-6|GABAA Agonist |

Case Studies in Marine Systems

Shelled Marine Gastropods

Shelled marine gastropods provide an instructive case study due to their extensive fossil record and traditional reliance on morphological characters for identification. A comprehensive review of recently published literature revealed that most gastropod species discussed were not cryptic [10]. To the degree that the sampled species represent extinct taxa, the results suggest that a high proportion of shelled marine gastropod species are identifiable for study in the fossil record [10]. This finding has significant implications for paleontological studies that rely on morphological characters to identify species and interpret evolutionary patterns.

Chaetoceros Curvisetus Diatom Complex

Research on the Chaetoceros curvisetus complex demonstrates how phylogenetic haplotype networks applied to global metabarcoding datasets can resolve cryptic species [13]. Despite only two morphologically described species (C. curvisetus and C. pseudocurvisetus), molecular analyses revealed approximately eleven genetically distinct taxa [13]. The study found:

- Absence of barcoding gap between some closely related species

- Variable distribution patterns with some species widely distributed and others restricted

- Evidence for ecological differentiation driving speciation

- Successful application of evolutionary approaches to metabarcoding data for systematic and phylogeographic studies

Stygocapitella Subterranea Annelid Complex

The interstitial meiofaunal annelid Stygocapitella subterranea was long considered a cosmopolitan species until molecular analyses revealed a complex of eight new species [12]. This case study demonstrated:

- With one exception, all newly described species were present along a single coastline

- No diagnostic morphological characters were found to differentiate species

- Both traditional diagnostic features and quantitative morphology failed to recognize species boundaries

- Evidence was found for both historical oceanic transitions and potential recent human-mediated translocations

This study fundamentally challenged the notion of cosmopolitan distributions for this meiofaunal group and highlighted how cryptic species can bias biodiversity assessments and biogeographic interpretations [12].

Ecological and Evolutionary Implications

Impacts on Biodiversity Assessment

The prevalence of cryptic species has profound implications for how we measure, monitor, and conserve marine biodiversity. In fragmented territories like French Polynesia, where inventory completeness rates range from 1.9% to 98.4% across archipelagos and islands, cryptic species further complicate biodiversity assessments [11]. The discovery of cryptic species often drastically reduces the perceived distribution range of individual species, as observed in the Stygocapitella complex where eight newly described species replaced a single "cosmopolitan" species [12].

This taxonomic resolution has direct consequences for understanding biodiversity patterns and processes:

- Biogeographic breaks may be more pronounced than previously recognized

- Endemism rates are likely higher in many marine groups

- Conservation prioritization must account for hidden genetic diversity

- Biomonitoring programs require molecular verification of target species

Implications for Marine Biodiversity Hotspots

Cryptic species complexes present particular challenges in marine biodiversity hotspots, where sampling biases and incomplete inventories already hamper conservation planning [11]. In French Polynesia, spatial and temporal sampling biases were partly explained by accessibility constraints (proximity to airports, roads, or ports), and inventory completeness was higher for marine than terrestrial species [11]. These biases challenge our ability to conduct integrated biogeographic analyses that account for the land-sea meta-ecosystem [11].

Molecular tools like DNA barcoding and metabarcoding hold great potential for biodiversity monitoring in these regions, possibly outperforming traditional taxonomic methods [14]. However, these approaches are limited by the availability of sequences in reference databases, with current assessments indicating approximately 85% of marine animal species still lack COI barcodes [14].

Cryptic species represent both a challenge and opportunity for marine biodiversity science. As molecular tools become more accessible and integrated into biodiversity monitoring, our understanding of species boundaries, distributions, and evolutionary relationships continues to evolve. The study of cryptic species emphasizes the complexity of biodiversity and the need for molecular tools in modern taxonomy and conservation [9].

Future research directions should include:

- Expanded barcoding initiatives to fill critical gaps in reference databases

- Integrated taxonomic approaches combining morphological, ecological, and molecular data

- Standardized sampling protocols to enable comparative analyses across regions

- Long-term monitoring that incorporates cryptic diversity into assessment frameworks

As we move toward more comprehensive characterization of species diversity across fragmented marine territories, explicitly acknowledging and addressing the biases inherent in biodiversity datasets is the crucial first step toward effective conservation and management strategies [11]. The systematic recognition and description of cryptic species is of seminal importance for accurate biodiversity assessments, biogeographic interpretations, and evolutionary studies in marine systems [12].

Cryptic species—discrete species that are difficult or impossible to distinguish morphologically—represent a significant component of Earth's undocumented biodiversity [15]. DNA-based studies are revealing that cryptic species exist across all major taxonomic groups and ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to extreme polar environments [15] [16]. Marine biodiversity hotspots, characterized by exceptionally high species richness and endemism, serve as particularly fertile ground for the emergence and maintenance of this cryptic diversity [17] [18]. The Central Indo-Pacific Ocean, Western Indian Ocean, and Central Pacific Ocean harbor especially high levels of marine biodiversity across multiple dimensions [19], creating ideal conditions for cryptic speciation. Understanding why these hotspots function as cradles for cryptic diversity requires examining the interplay of historical biogeography, ecological opportunity, and evolutionary processes that drive diversification while maintaining morphological stasis.

This whitepaper examines the principal evolutionary mechanisms driving cryptic diversification in biodiversity hotspots, with a specific focus on marine ecosystems. We synthesize current research on patterns of cryptic species distribution, analyze the methodological frameworks for their detection, and explore the implications for conservation biology and pharmaceutical discovery. By integrating phylogeographic evidence, molecular data, and ecological theory, we provide a comprehensive technical framework for researching cryptic diversity in the world's most biologically rich marine environments.

Theoretical Framework and Evolutionary Drivers

Conceptual Models of Hotspot Dynamics

The formation and persistence of biodiversity hotspots can be understood through several conceptual frameworks that explain their dynamic nature over geological timescales. The "hopping hotspot" hypothesis proposes that biodiversity hotspots are not static but migrate across regions in response to tectonic activity and environmental changes [17]. Evidence suggests a westward migration from the Tethys Sea during the Eocene (42-39 million years ago) to the Arabian region by the late Miocene (approximately 20 million years ago), and finally to the Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA) by the Pleistocene (approximately 1 million years ago) [17]. In contrast, the "centers-of" hypotheses provide complementary explanations for the IAA's exceptional diversity: the center of origin model emphasizes high speciation rates within the region; the center of accumulation highlights preferential colonization by species from elsewhere; the center of overlap describes convergence of distinct biogeographic faunas; and the center of survival proposes the region as a refuge with low extinction rates [17].

The integrated "Dynamic Centers Hypothesis" synthesizes these perspectives, proposing that as biodiversity hotspots migrate, their role in generating and sustaining biodiversity evolves, with different sources dominating distinct historical phases [17]. This dynamic framework helps explain why hotspots accumulate not only taxonomic diversity but also high levels of cryptic diversity through repeated cycles of isolation, adaptation, and persistence.

Evolutionary Mechanisms Promoting Cryptic Speciation

Table 1: Evolutionary Drivers of Cryptic Diversity in Marine Hotspots

| Driver Category | Specific Mechanism | Effect on Cryptic Speciation | Representative System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical/Geological | Habitat fragmentation during Pleistocene glaciations | Population isolation and genetic divergence without morphological differentiation | Giraffes (6 cryptic species) [15] |

| Tectonic activity creating barriers | Vicariant speciation in allopatry | Amazonian leaflitter frogs [15] | |

| Environmental | Glacial advances scouring continental shelves | Population bottlenecks and refuge isolation | Southern Ocean marine fauna [16] |

| Sea-surface temperature gradients | Adaptive divergence to thermal niches | Global marine taxa [19] | |

| Biological/Ecological | Assortative mating based on non-morphological cues | Reproductive isolation despite morphological similarity | Giraffe coat patterns [15] |

| Specialization to specific microhabitats | Ecological speciation without morphological change | Symbiotic associations across environmental gradients [20] |

Several interconnected evolutionary mechanisms drive cryptic diversification in biodiversity hotspots:

Refugial Dynamics and Population Bottlenecks: Climate oscillations, particularly during the Pleistocene, repeatedly fragmented habitats, isolating populations in refugia [15] [16]. For example, increasing aridity and expansion of the Mega Kalahari desert fragmented giraffe populations, leading to divergence of at least six lineages between 1.6 million years and 113,000 years ago [15]. Similarly, in the Southern Ocean, repeated glacial advances (at least 38 events in the past 5 million years) annihilated continental shelf communities, forcing species into isolated refugia at localized deep areas, offshore habitats, or peri-Antarctic islands [16].

Environmental Gradients and Adaptive Divergence: Abiotic factors like sea-surface temperature create selective pressures that drive genetic adaptation without necessarily affecting morphology [19] [20]. Spatial analysis reveals significant correlations between sea-surface temperature and marine genetic diversity, suggesting temperature-associated adaptive divergence [19]. Similarly, studies of endophytic fungi across boreal forest climate gradients show strong climatic signatures in genetic structure independent of morphological variation [20].

Non-morphological Reproductive Barriers: Pre-zygotic isolation mechanisms such as differences in reproductive timing, chemically-mediated mate recognition, or imprinted assortative mating based on visual cues like coat patterns can maintain reproductive isolation between cryptic lineages without morphological differentiation [15].

Patterns and Case Studies of Cryptic Diversity

Quantitative Distribution of Cryptic Diversity

Table 2: Documented Cryptic Diversity Across Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Reported Cryptic Species | Geographic Focus | Primary Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine shelled gastropods | Variable proportion; most species not cryptic | Global oceans | Multi-locus genetic analysis [10] |

| Notothenioid fishes | Multiple cryptic lineages (e.g., Lepidonotothen nudifrons) | Southern Ocean | Mitochondrial & nuclear DNA [16] |

| Insects | 996 new cryptic species | Global meta-analysis | DNA barcoding [15] |

| Mammals | 267 cryptic species | Africa (e.g., giraffes) | mtDNA & microsatellites [15] |

| Amazonian frogs | 3 highly divergent cryptic clades | Upper Amazon | mtDNA & microsatellites [15] |

Analysis of cryptic species distribution reveals several important patterns. First, cryptic species are not uniformly distributed across taxa or regions. In shelled marine gastropods, for instance, most species are not considered cryptic, suggesting that many species can be confidently identified and studied in both living and fossil taxa [10]. This finding challenges the assumption that cryptic species represent a uniformly large proportion of all biodiversity.

Second, cryptic diversity appears disproportionately common in certain environments. Among Antarctic invertebrates, independently evolving lineages that remain morphologically indistinguishable are disproportionately common compared to other marine areas [16]. This pattern may reflect the extreme environmental conditions and historical glaciations that have shaped these ecosystems.

Third, the age of cryptic lineages varies substantially. While some cryptic species are the product of recent speciation events, others have ancient origins. For example, cryptic lineages within the upper Amazonian leaflitter frog (Eleutherodactylus ockendeni) date back to late Oligocene and late Miocene (approximately 24-9 million years ago), coinciding with major geotectonic events in the northern Andes rather than Quaternary climatic cycles [15].

Hotspots as Reservoirs of Cryptic Diversity

Marine biodiversity hotspots concentrate not only taxonomic diversity but also genetic and phylogenetic diversity [19]. The Central Indo-Pacific Ocean, Central Pacific Ocean, and Western Indian Ocean harbor high levels of biodiversity across all three dimensions, making them priority areas for conservation [19]. The Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA), in particular, stands out as the world's preeminent marine biodiversity hotspot, distinguished by its exceptional species richness in tropical shallow waters [17].

These hotspots function as cradles for cryptic diversity through several mechanisms. Their complex habitat heterogeneity provides numerous ecological niches and microhabitats that promote specialization and divergence [17]. Their location at the intersection of different biogeographic realms facilitates the overlap of distinct evolutionary lineages [17]. Additionally, their relative environmental stability over evolutionary timescales has served as a refuge during periods of global climate change, preserving ancient lineages [17].

The conservation significance of these cryptic diversity hotspots is substantial. Current fully protected marine areas conserve only 34% of known taxonomic diversity, 63% of genetic diversity, and 54% of phylogenetic diversity [19]. In contrast, strategically protecting approximately 22% of the ocean would safeguard 95% of taxonomic diversity, 99% of genetic diversity, and 97% of phylogenetic diversity [19].

Methodological Framework for Cryptic Species Detection

Integrated Workflow for Species Delimitation

The detection and confirmation of cryptic species requires an integrated methodological approach combining multiple lines of evidence. The following workflow visualization outlines a comprehensive protocol for cryptic species identification:

Diagram 1: Species Delimitation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cryptic Species Research

| Reagent/Material | Specific Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial DNA primers (COI, Cytb, ND1) | DNA barcoding & phylogenetic analysis | Amplification of standardized gene regions for species identification and divergence estimation |

| Microsatellite markers | Population genetics & gene flow assessment | Detection of nuclear genetic structure and reproductive isolation |

| Taq polymerase & PCR reagents | DNA amplification | In vitro replication of specific DNA sequences for analysis |

| Restriction enzymes | RADseq or similar methods | Genome reduction for SNP discovery and genotyping |

| Sanger sequencing reagents | DNA sequence determination | Determination of nucleotide sequences for phylogenetic analysis |

| RNA later preservative | Tissue sample preservation | Stabilization of RNA and DNA in field-collected specimens |

| Agarose & electrophoresis systems | DNA fragment separation | Size-based separation of DNA fragments for quality control |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) filters | Non-invasive sampling | Collection of genetic material from water or soil samples |

| 5-Hydroxy-7-acetoxyflavone | 5-Hydroxy-7-acetoxyflavone | 5-Hydroxy-7-acetoxyflavone (CAS 6674-40-4), a natural flavone derivative for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| L-DOPA-2,5,6-d3 | L-DOPA-2,5,6-d3|Deuterated Levodopa|CAS 53587-29-4 | L-DOPA-2,5,6-d3 is a deuterated internal standard for precise LC-MS quantification of dopamine pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Specimen Collection and Preservation: Collect specimens across the target species' entire range. Immediately preserve tissue samples in 95% ethanol or RNA later at -20°C. Record precise collection localities using GPS.

DNA Extraction and Quantification: Use standard phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial kit protocols. Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometry or spectrophotometry. Ensure minimum quality thresholds (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0).

PCR Amplification of Target Loci: Amplify mitochondrial genes (COI, Cytb) and nuclear markers (microsatellites, introns) using optimized protocols. For COI, use universal primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 with thermal profile: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 48°C for 45s, 72°C for 60s; final extension at 72°C for 5-10 min.

Sequencing and Alignment: Purify PCR products and sequence in both directions. Assemble contigs, align sequences using MUSCLE or MAFFT with default parameters. Visually inspect alignments for errors.

Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct gene trees using Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) and Bayesian Inference (MrBayes). Use appropriate substitution models selected by ModelTest. Run analyses until convergence (average standard deviation of split frequencies <0.01).

Species Delimitation: Apply multiple species delimitation methods (ABGD, bPTP, GMYC) to concordantly identify independently evolving lineages.

Population Genetic Structure Analysis Protocol

Microsatellite Genotyping: Amplify 10-20 polymorphic microsatellite loci using fluorescently labeled primers. Separate fragments on capillary sequencer and score alleles against size standards.

Genetic Diversity Metrics: Calculate observed and expected heterozygosity, allelic richness, and nucleotide diversity using packages like Arlequin or GenAlEx.

Population Structure: Analyze using Bayesian clustering (STRUCTURE), discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC), and F-statistics. Assess hierarchical population structure with AMOVA.

Gene Flow Estimation: Calculate contemporary migration rates using Bayesian methods (BAYESASS) and coalescent-based approaches (MIGRATE-N).

Implications for Conservation and Drug Discovery

Conservation Priorities and Protected Area Design

The discovery of cryptic species has profound implications for conservation biology, particularly in marine biodiversity hotspots. Traditional conservation planning based solely on morphological taxonomy may significantly underestimate true diversity and fail to protect evolutionarily distinct lineages [15] [21]. This is particularly critical for the 34 recognized biodiversity hotspots worldwide, which were originally defined primarily using vertebrates and plants while overlooking hyperdiverse groups like insects, fungi, and marine taxa [21].

Integrating molecular data into conservation planning reveals that strategically protecting approximately 22% of the ocean would conserve 95% of known taxonomic diversity, 99% of genetic diversity, and 97% of phylogenetic diversity [19]. This approach allows for the identification of cryptic biodiversity reservoirs such as peri-Antarctic islands, which harbor previously undocumented vertebrate diversity despite their extreme isolation [16]. Furthermore, even heavily modified urban environments can function as unexpected reservoirs of cryptic diversity, as demonstrated by the endangered shortnose sturgeon population in New York Harbor that contains unique behavioral phenotypes [22].

Modern conservation frameworks must incorporate multifaceted biodiversity assessments including taxonomic, genetic, and phylogenetic dimensions [19] [17]. This requires systematic population sampling, particularly in tropical rainforests and developing countries where cryptic diversity remains most undocumented [15]. The implementation of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding provides a powerful tool for biodiversity monitoring in marine protected areas, enabling comprehensive community assessments without extensive morphological identification [18].

Bioprospecting Implications for Pharmaceutical Development

Cryptic species in marine biodiversity hotspots represent an largely untapped resource for pharmaceutical discovery. The following diagram illustrates how cryptic diversity exploration can enhance bioprospecting pipelines:

Diagram 2: Bioprospecting Enhanced by Cryptic Diversity

Marine hotspots harbor not only high species diversity but also exceptional chemical diversity with pharmaceutical potential. Cryptic species often possess unique biochemical profiles resulting from their distinct evolutionary trajectories and ecological specializations [17] [18]. The exploration of these previously overlooked lineages increases the probability of discovering novel bioactive compounds with unique mechanisms of action.

The rich symbiotic associations found in marine hotspots, particularly in the IAA, represent promising sources of pharmaceutical leads [20] [18]. These complex holobiont systems—such as sponges, corals, and their microbial symbionts—have co-evolved intricate chemical communication systems that include antibacterial, antifungal, and antipredator compounds [18]. As many of these symbiotic relationships are highly specific, the discovery of cryptic host species often reveals previously unknown microbial symbionts with unique metabolic capabilities.

Marine biodiversity hotspots function as cradles for cryptic diversity through the complex interplay of historical biogeography, environmental heterogeneity, and ecological opportunity. The evolutionary drivers outlined in this technical guide—including refugial dynamics, environmental gradients, and non-morphological reproductive barriers—promote genetic divergence and speciation while maintaining morphological stasis. Advanced molecular methodologies now enable researchers to detect and describe this hidden biodiversity, revealing that cryptic species represent a substantial component of global diversity with significant implications for conservation planning and bioprospecting.

As research in this field advances, integrating multifaceted approaches that combine taxonomic, genetic, and phylogenetic dimensions will be essential for fully understanding and protecting the evolutionary processes that generate and maintain biodiversity in these critical regions. The dynamic nature of hotspots underscores the importance of considering both current patterns and historical processes in biodiversity research and conservation implementation.

The ocean, encompassing over 70% of the Earth's surface and representing its largest habitat, possesses greater biodiversity than terrestrial ecosystems [23] [24]. This biological richness translates to extraordinary chemodiversity, with marine organisms producing structurally novel bioactive compounds that modulate human disease targets through unique mechanisms of action [23]. The evolutionary pressure exerted by marine environments—including extreme conditions of temperature, pressure, salinity, and low light—has driven the development of sophisticated chemical defense strategies in many marine invertebrates, which lack physical defenses or immune systems [23] [24]. These defense molecules often exhibit ideal drug-like properties, including the ability to traverse biological barriers and interact with specific molecular targets, making them particularly valuable for pharmaceutical development [23]. The field of marine pharmaceuticals has evolved from early discoveries in the 1950s to a mature discipline that has yielded approximately 15-20 clinically approved drugs, predominantly for cancer treatment and pain management, with many more in clinical development [23] [24].

The commercial significance of marine-derived pharmaceuticals is demonstrated by substantial market growth and valuation projections. The global marine pharmaceuticals market continues to expand rapidly, driven by increasing demand for novel therapeutic agents and advancements in marine biotechnology.

Table 1: Marine Pharmaceuticals Market Projections

| Market Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2034/2035 Projection | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 6.19 billion (2024) [25] | USD 10.34 billion (2034) [25] | 5.29% [25] | Unique marine biodiversity, chronic disease prevalence, biotechnology advances [25] |

| Alternative Market Size | USD 4,177.9 million (2025) [26] | USD 9,264.04 million (2035) [26] | 8.3% [26] | Demand for natural therapies, anti-infective needs, sustainable sourcing [26] |

| Oncology Segment | USD 1.44 billion (2018) [27] | Significant growth by 2028 [27] | - | Rising cancer prevalence, novel mechanisms of action [27] |

Regional market analysis reveals that North America dominates with approximately 40% market share, supported by well-established biotechnology infrastructure, significant research funding from agencies like NOAA and NIH, and high prevalence of chronic diseases [25] [27]. The Asia-Pacific region is projected to witness the fastest growth rate during 2025-2034, fueled by rich marine biodiversity, increasing investments in marine research, and government support in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea [25].

Therapeutic application segmentation shows that oncology/anticancer applications hold the largest market share (30-35%), while the anti-infective segment is expected to grow at the fastest CAGR, driven by the global antimicrobial resistance crisis [25]. By product type, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) constitute approximately 40% of the market, with semi-synthetic/synthetic derivatives exhibiting the most rapid growth as they enhance stability and potency while improving production scalability [25].

Historical Success Stories: From Sea to Clinic

The historical trajectory of marine pharmaceutical discovery demonstrates a compelling narrative of scientific innovation, beginning with foundational discoveries in the mid-20th century.

Table 2: Historically Significant Marine-Derived Pharmaceuticals

| Compound/Drug | Marine Source | Year/Period | Clinical Application | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spongothymidine & Spongouridine | Caribbean sponge Tethya crypta (later renamed Cryptothethya crypta) [23] | 1940s-1950s [23] | Lead compounds for synthetic antiviral and anticancer drugs [23] | First marine-derived bioactive compounds; inspired development of Ara-C (cytarabine) and Ara-A [23] |

| Cytarabine (Ara-C) | Synthetic derivative inspired by sponge nucleosides [23] [24] | Approved 1969 [23] | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, meningeal leukemia [24] | First marine-inspired drug approved; antimetabolite/antineoplastic agent [24] |

| Ziconotide | Cone snail (Conus magus) [24] | Approved 2004 [24] | Chronic pain management [24] | Potent analgesic (1000x more potent than morphine); calcium channel blocker [24] |

| Eribulin (Halaven) | Synthetic analog of halicondrin B from sponge Halichondria okadai [24] | Approved 2010 (USA) [24] | Advanced breast cancer, liposarcoma [24] | Macrocyclic ketone analog; inhibits cell growth in multiple cancer lines [24] |

| Bryostatin | Bryozoan Bugula neritina [24] | Clinical trials [24] | Cancer, Alzheimer's disease, anti-HIV [24] | Protein kinase C modulator; demonstrates diverse therapeutic potential [24] |

The discovery of spongothymidine and spongouridine from the Caribbean sponge Tethya crypta by Bergmann and Feeney in the 1940s-1950s represented the pivotal starting point for marine pharmaceuticals [23]. These novel nucleosides containing arabinose sugar moieties inspired synthetic chemists to develop analogs that would eventually become the first marine-inspired drugs approved for human use [23]. The subsequent approval of cytarabine (Ara-C) for leukemias established that marine organisms could yield clinically significant therapeutics, paving the way for future marine drug discovery efforts [23] [24].

The progression from initial discovery to clinical application typically follows an extended timeline, often spanning decades. This process involves multiple stages including biomass collection, extract preparation, bioactivity screening, compound isolation, structural elucidation, mechanism of action studies, and extensive preclinical and clinical development [23]. The supply chain challenge has been addressed through various innovative approaches including aquaculture, mariculture, and semi-synthetic production, as total synthesis of complex marine natural products is often economically unfeasible [24].

Cryptic Biodiversity: Hidden Diversity in Marine Ecosystems

Cryptic biodiversity—the presence of morphologically similar but genetically distinct species—presents both challenges and opportunities for marine bioprospecting. Molecular genetic studies have revealed that many supposedly widespread marine species actually comprise complexes of multiple evolutionary lineages, with significant implications for bioprospecting efforts.

The ascidian Pyura stolonifera, an important ecosystem engineer dominating temperate coastal communities in the southern hemisphere, exemplifies this phenomenon. Genetic analyses using mitochondrial COI and nuclear markers (ANT, ATPSα, 18S) have revealed "nested cryptic diversity" within this taxon, with at least five distinct species further subdivided into smaller-scale genetic lineages [28]. This complex genetic structure initially created uncertainty about whether populations in Africa, Australasia, and South America represented the fragmented remains of a pan-Gondwanan species or recent introductions through human activities [28].

The implications of cryptic diversity for bioprospecting are substantial:

- Chemodiversity Potential: Genetically distinct lineages often produce different suites of bioactive compounds as part of their chemical defense systems, expanding the potential for novel drug discovery within a single morphological species [28].

- Sustainable Sourcing: Identifying the correct genetic lineage is crucial for developing sustainable sourcing strategies, as different lineages may require different aquaculture or conservation approaches [28].

- Benefit Sharing: Understanding the true geographic distributions of evolutionary units is essential for equitable benefit-sharing arrangements, a key consideration under international agreements like the Nagoya Protocol [28].

- Quality Control: Ensuring consistent genetic identity of source organisms is critical for reproducible production of marine-derived pharmaceuticals [28].

Similar patterns of cryptic diversity have been documented across diverse marine taxa, suggesting that the phenomenon is widespread in marine ecosystems. This hidden diversity represents a largely untapped resource for discovering novel bioactive compounds with unique mechanisms of action [28].

Methodological Framework: From Collection to Clinical Candidate

The discovery and development of marine-derived pharmaceuticals follows a systematic workflow that integrates traditional natural product chemistry with modern technological approaches.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Marine bioprospecting begins with the strategic collection of marine organisms from diverse ecosystems, including extreme environments [23]. Sampling approaches must consider cryptic biodiversity by collecting from multiple habitats and biotic zones within a region [28]. Proper documentation and preservation of voucher specimens is essential for taxonomic identification and future recollection [23]. For marine invertebrates and microorganisms, biomass is typically extracted using organic solvents, followed by removal of solvents to generate crude extracts potentially containing hundreds to thousands of compounds [23].

Bioactivity Screening and Compound Isolation

The subsequent workflow involves multiple stages of fractionation and testing:

- Initial fractionation to remove water-soluble compounds (salts, sugars) and highly lipophilic compounds (fats) [23]

- Biological screening using assays relevant to human diseases, particularly focusing on unmet medical needs [23]

- Bioassay-guided fractionation through iterative chromatographic purification and activity testing to pinpoint bioactive compounds [23]

- Dereplication using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to identify known compounds and focus efforts on novel bioactives [23]

- Structural elucidation of pure bioactive compounds using mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [23]

Advanced Technologies in Marine Drug Discovery

Contemporary marine pharmaceutical discovery employs sophisticated technologies that enhance efficiency and success rates:

- Genome Mining: Identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in marine microorganisms predicts their capacity to produce novel bioactive compounds [29]. Tools like antiSMASH facilitate BGC identification, though novel BGCs may be overlooked due to reference-based algorithms [29].

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS): Metagenomic analysis of marine microbial communities without cultivation, using specific gene regions or barcodes to assess genetic diversity and biosynthetic potential [24].

- HTS combined with LC-MS/NMR: Increased sensitivity and specificity in compound identification through integrated omics approaches [24].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): Prediction of structure-activity relationships and biological targets of marine natural products; systems like AlphaFold predict 3D protein structures to facilitate target identification [24].

- Heterologous Expression: Production of marine-derived compounds by expressing BGCs in culturable microbial hosts to overcome supply limitations [23].

- Semi-synthetic Derivatization: Chemical or enzymatic modification of marine-derived lead compounds to enhance stability, potency, and pharmacokinetic properties while maintaining structural novelty [25] [24].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Marine Pharmaceutical Discovery

| Reagent/Technology | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Genetic analysis of cryptic diversity; genome mining | Salting-out protocol for ascidian tissue [28] |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | Amplification of taxonomic and biosynthetic genes | Custom primers (e.g., StolidoANT-F for ascidian ANT gene) [28] |

| LC-MS Systems | Dereplication; compound identification | Analysis of extracts and fractions to identify novel vs. known compounds [23] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Structural elucidation of novel compounds | Determination of complex structures with novel skeletons [23] |

| HTS Screening Platforms | Bioactivity assessment | Disease-relevant assays for cancer, infectious diseases, inflammation [24] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | BGC identification; sequence analysis | antiSMASH for BGC prediction; phylogenetic analysis software [29] |

| Aquaculture Systems | Sustainable biomass production | In-sea and on-land aquaculture for species like bryozoan [24] |

| Fermentation Bioreactors | Microbial culture and compound production | Large-scale fermentation of marine microorganisms [23] |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite notable successes, marine pharmaceutical discovery faces several significant challenges that must be addressed to fully realize the potential of marine biodiversity.

Technical and Development Challenges

The "valley of death" in drug development describes the difficulty in advancing promising lead compounds to clinical candidates [27]. For marine-derived leads, this transition requires comprehensive mechanism of action studies, structure-activity relationship characterization, pharmaceutical property assessment, pharmacokinetic profiling, and medicinal chemistry optimization [27]. The complex structural features of many marine natural products often make total synthesis economically unfeasible, necessitating alternative approaches such as semi-synthesis, aquaculture, or heterologous expression [24].

Supply chain sustainability remains a critical consideration, as many marine source organisms occur in low abundances or fragile ecosystems [23]. Innovative solutions include the development of aquaculture for species such as the bryozoan Bugula neritina (bryostatin source), which has been successfully cultivated through both in-sea and on-land systems [24]. For marine microorganisms, fermentation-based production offers a scalable alternative, though it requires optimization of growth conditions and nutrient media [23].

Biodiversity Conservation and Ethical Considerations

The exploration of marine genetic resources raises important questions about equitable benefit-sharing, particularly given that benefits currently flow disproportionately to economically powerful states and corporations [30]. International agreements, including the Nagoya Protocol, aim to ensure fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources [30].

The phenomenon of cryptic biodiversity complicates these efforts, as the true geographic distributions of evolutionary units may not align with political boundaries [28]. Comprehensive sampling across a species' range is essential to accurately determine biogeographic patterns and establish appropriate benefit-sharing frameworks [28].

Future Prospects

Future advances in marine pharmaceutical discovery will likely focus on several key areas:

- Unexplored Ecosystems: Deep-sea and extreme environments harbor specially adapted organisms with unique metabolic capabilities, representing a promising resource for novel bioactive compounds [24] [29].

- Synergistic Combinations: Research into synergistic interactions between marine-derived compounds may enhance efficacy and combat drug resistance [29].

- Targeted Delivery Systems: Antibody-drug conjugates linking marine cytotoxins to targeted antibodies represent an emerging approach to enhance therapeutic specificity [23].

- Sustainable Exploration: Advances in marine biotechnology, including in situ cultivation and microbiome engineering, will enable more sustainable exploration of marine pharmaceutical resources [24] [26].

The historical success of marine-derived pharmaceuticals demonstrates the profound medical potential residing in marine biodiversity. From the initial discovery of novel nucleosides in Caribbean sponges to contemporary approved drugs for cancer and pain, marine natural products have established a compelling track record of clinical utility. The recognition of cryptic biodiversity within marine ecosystems reveals an even greater chemical diversity than previously appreciated, with distinct evolutionary lineages representing unique reservoirs of bioactive compounds.

The continued exploration of this resource requires interdisciplinary approaches that integrate marine biology, natural product chemistry, genomics, and drug development expertise. As technological advances facilitate the discovery and production of marine-derived therapeutics, and with international frameworks evolving to ensure equitable benefit-sharing, marine pharmaceuticals are poised to make increasingly significant contributions to addressing unmet medical needs. The future of this field lies in balancing aggressive bioprospecting with conscientious conservation, ensuring that marine ecosystems continue to provide novel therapeutic agents for generations to come.

The Mesoamerican Reef (MAR) represents one of the most valuable coral reef systems in the Northern Hemisphere, yet its full biological diversity remains incompletely characterized [31]. This technical guide examines the critical knowledge gap between known and undocumented biodiversity within this and similar marine hotspots, framing the issue within the broader context of cryptic biodiversity research. As climate change and anthropogenic pressures accelerate, quantifying this gap becomes increasingly urgent for developing effective conservation strategies and understanding the true scale of potential biodiversity loss [31]. We synthesize current assessment methodologies, present quantitative data on documented species, and outline protocols for detecting the cryptic diversity that conventional surveys overlook, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for biodiversity inventory in complex marine ecosystems.

The Documented Biodiversity of the Mesoamerican Reef

Current Ecological Health Indicators

Systematic monitoring programs, such as the Healthy Reefs Initiative, have established quantitative baselines for key ecological indicators across the MAR. The 2024 Reef Health Report Card evaluated 286 sites, providing a snapshot of the system's known ecological state [32]. The data reveal an ecosystem under significant stress, with only 10% of sites rated in "good" or "very good" condition.

Table 1: Ecosystem Health Indicators in the Mesoamerican Reef (2024 Assessment)

| Indicator | Status | Trend (2021-2023) | Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reef Health Index (RHI) | Poor | Improving | 2.3 → 2.5 (out of 5) |

| Coral Cover | Fair | Declining | 19% → 17% |

| Herbivorous Fish Biomass | Fair | Increasing | 1,843 → 2,419 g/100m² |

| Commercial Fish Biomass | Poor | Stable (except Belize) | Belize: 330 → 791 g/100m² |

| Fleshy Macroalgae | Poor | Not Specified | Not Specified |

The documented decline in coral cover from 19% to 17% between 2021 and 2023 is primarily attributed to disease and bleaching events, with all reefs exposed to severe heat stress during the monitoring period [32]. Notably, approximately 40% of corals experienced severe bleaching in 2023, with significant mortality events occurring post-monitoring in iconic sites like Banco Cordelia in Honduras, where live coral cover plummeted from 46% to 5% between September 2023 and February 2024 [32].

Structurally Complex Coral Assemblages

The architectural complexity provided by specific coral taxa is a critical determinant of overall reef biodiversity. Research identifies Orbicella annularis and Orbicella faveolata as crucial for maintaining the structural complexity and associated biodiversity in the central and southern zones of the MAR's northern sector [33]. These framework-building species create the three-dimensional habitats that support diverse fish and invertebrate communities.

A 2016 study of 158 sites across the MAR revealed that only 13% were "hotspots" containing more than 10% live coral cover of these key structural species (competitive and stress-tolerant corals) [31]. The distribution of these hotspots showed a spatial mismatch with existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), highlighting a significant conservation gap. Only 30% of these critical sites benefiting from full protection within Replenishment Zones, where all extractive activities are prohibited [31].

Methodologies for Biodiversity Assessment

Conventional Ecological Monitoring Protocols

The quantitative data presented in Section 2 derive from standardized monitoring protocols that have been systematically implemented across the MAR:

- Video Transect Surveys: The foundational methodology for benthic community assessment involves 50m long by 0.4m wide video transects, with subsequent frame-by-frame analysis to quantify species richness and percentage cover [33]. Typically, 40 frames are reviewed per transect, with 13 fixed points systematically distributed to record coral species presence and abundance.

- Reef Health Index Calculation: This composite metric integrates multiple indicators (coral cover, fleshy macroalgae, herbivorous and commercial fish biomass) into a single score on a 5-point scale, allowing for standardized comparison across sites and temporal trends [32].

- Habitat Area Estimation: Satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat TM) combined with supervised classification in programs like ERDAS enables quantification of reef habitat area, a key variable influencing biodiversity patterns [33].

Molecular Approaches for Cryptic Diversity Detection

Traditional morphological surveys significantly underestimate true diversity, particularly for taxonomically challenging groups. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful complementary tool for revealing cryptic species complexes.

- Sample Collection: Extensive specimen collection across biodiversity hotspots provides the foundational material for analysis. For example, a study on plateau loach in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau collected 1,630 specimens to assess cryptic diversity [34].

- DNA Extraction and COI Amplification: Standard DNA extraction followed by PCR amplification of a ~650 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene using universal primers [34].

- Sequence Analysis: Sequencing and alignment of COI sequences (typically trimmed to a consensus length of 606 bp) with analysis of nucleotide composition, variable sites, and haplotype diversity [34].

- Molecular Operational Taxonomic Unit (MOTU) Delineation: Application of multiple analytical methods to identify putative species:

- Poisson Tree Processes (PTP) Model: Uses phylogenetic tree branch lengths to identify speciation events [34].

- General Mixed Yule-Coalescent (GMYC) Model: Distinguishes between coalescent (population-level) and Yule (species-level) processes on phylogenetic trees [34].

- Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD): Partitions sequences into MOTUs based on the presence of a "barcode gap" in genetic distances [34].

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for comprehensive biodiversity assessment combining traditional morphological surveys and modern molecular approaches.

The Known Unknowns: Quantifying the Biodiversity Gap

Limitations of Conventional Biodiversity Inventories

The gap between documented and actual diversity stems from several methodological and taxonomic limitations:

- Cryptic Species Complexes: Morphologically similar but genetically distinct species are common in marine environments. DNA barcoding studies regularly reveal 10-30% more MOTUs than morphospecies in well-studied groups [34].

- Taxonomic Resolution Gaps: Global barcoding coverage varies significantly among phyla. As of 2021, only 14.2% of known marine species had been barcoded, with dramatic disparities between groups (Chordata: 74.7% vs. Porifera: 4.8%) [14].

- Inadequate Spatial Coverage: Even in monitored systems like the MAR, sampling intensity varies geographically, with remote or deep areas frequently under-surveyed [35].

DNA Barcoding Coverage Across Marine Taxa

The uneven progress in molecular characterization of marine species creates significant blind spots in biodiversity assessments:

Table 2: DNA Barcoding Coverage Across Major Marine Phyla in Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs)

| Phylum | Barcoding Coverage | Representation in Reference Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Chordata | High (74.7%) | Well-represented |

| Arthropoda | Moderate | Fairly represented |

| Mollusca | Moderate | Fairly represented |

| Porifera | Low (4.8%) | Highly underrepresented |

| Bryozoa | Low | Highly underrepresented |

| Platyhelminthes | Low | Highly underrepresented |

This coverage disparity means biodiversity assessments for well-studied groups like fishes may be relatively complete, while those for sponges and other poorly-barcoded taxa significantly underestimate true diversity [14]. Between 2011 and 2021, the percentage of barcoded marine species increased from 9.5% to 14.2%, indicating progress but still leaving the majority of marine species without molecular characterization [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Comprehensive Biodiversity Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function/Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Underwater Video Systems | Benthic community surveys | High-definition video recording along transects for later frame analysis of species composition and cover [33]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Molecular analysis | Standardized protocols for obtaining high-quality genomic DNA from tissue samples (fin clips, tissue biopsies) [34]. |

| COI Universal Primers | DNA barcoding | Amplification of ~650 bp cytochrome c oxidase I region for species identification and delimitation [34]. |

| GPS & GIS Software | Spatial mapping | Precise location data for survey sites; spatial analysis of biodiversity patterns and protected area coverage [31] [33]. |

| BOLD Database | Sequence repository | Reference database for comparing obtained sequences with known barcodes; identification of unknown specimens [14]. |

| (S)-Norzopiclone | N-Desmethylzopiclone | N-Desmethylzopiclone, an active metabolite of Zopiclone. A selective GABA-A receptor partial agonist for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| H-Abu-OH-d3 | L-Aminobutyric Acid-d3|CAS 929202-07-3 | L-Aminobutyric Acid-d3 (CAS 929202-07-3) is a deuterated internal standard for precise bioanalysis. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Quantifying the gap between known and unknown diversity in critical regions like the Mesoamerican Reef requires integrating traditional ecological monitoring with cutting-edge molecular techniques. While current data reveal an ecosystem under significant stress, with only 10% of sites in good health and key structural corals in decline, the true scale of biodiversity remains incompletely characterized [32] [31]. The documented increase in barcoded marine species from 9.5% to 14.2% over the past decade represents progress, but significant taxonomic gaps persist, particularly for non-vertebrate taxa [14].

Future research must prioritize the application of integrated assessment protocols, expanding molecular characterization to understudied taxa, and increasing spatial coverage to include mesophotic depths and remote areas. Only through such comprehensive approaches can we accurately quantify marine biodiversity and implement effective conservation strategies for these critically important ecosystems. The protection of the remaining hotspots of structural complexity, which currently show a spatial mismatch with existing fully protected zones, deserves particular urgency in conservation planning [31].

Advanced Tools for Detection: From eDNA Metabarcoding to Autonomous Monitoring

In the vast and complex realm of marine biodiversity hotspots, a significant portion of biological diversity remains undetected by traditional survey methods. Cryptic biodiversity—encompassing rare, elusive, and morphologically similar species—often evades visual census and capture-based techniques, creating substantial knowledge gaps in some of the world's most ecologically important regions [36] [37]. Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a revolutionary approach to address this challenge, enabling comprehensive biodiversity assessment through genetic traces organisms leave in their environment [38]. This transformative technology detects multi-species presence from water, sediment, or ice samples without direct observation or capture, making it particularly valuable for monitoring protected areas and detecting invasive or endangered species [38] [36]. In marine ecosystems, where traditional methods face limitations in scalability, detection sensitivity, and invasiveness, eDNA metabarcoding provides a non-invasive, cost-effective alternative that can uncover previously hidden components of biodiversity [36] [39]. This technical guide examines the core workflows, applications, and advancements in eDNA metabarcoding that are revolutionizing discovery in marine biodiversity research.

Core Technical Workflow: From Sample Collection to Data Interpretation

The standard eDNA metabarcoding workflow involves multiple critical stages, each requiring meticulous execution to ensure reliable results. The process begins with environmental sample collection and progresses through DNA extraction, sequencing, and sophisticated bioinformatic analysis.

Sample Collection and Preservation

Water sampling represents the most common approach in marine eDNA studies, with several collection methods validated for scientific use:

- Niskin Bottles: Deployed at specific depths (typically 5-150m), these devices provide depth-resolved samples and minimize surface contamination [39] [4]. They require the vessel to stop during deployment but are relatively easy to maintain contamination-free.

- Ship-Bottom Intake: Continuously samples water from several meters below the surface (approximately 4.5m) while the vessel is underway, enabling broader spatial coverage [39]. This method faces challenges with potential metal ion obstructions and maintaining a clean intake system.

- Surface Bucket Sampling: Collects water from the air-sea interface (0m depth), offering the simplest approach but limited to calm sea conditions [39]. Comparative studies indicate bucket sampling may show enhanced detection for some surface-associated species like Japanese jack mackerel and Pacific saury [39].

Recent research comparing these methods in the western North Pacific found that despite technical differences, all three approaches detected similar fish community compositions when sampling within the well-mixed surface layer [39]. This suggests methodological flexibility based on logistical constraints while maintaining scientific validity.