Unveiling the Hidden Symbiosis: How Algae-Archaea Interactions Drive Global Biogeochemical Cycles and Shape Our World

This article synthesizes current scientific knowledge on the understudied yet critical symbiotic relationships between algae and archaea.

Unveiling the Hidden Symbiosis: How Algae-Archaea Interactions Drive Global Biogeochemical Cycles and Shape Our World

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific knowledge on the understudied yet critical symbiotic relationships between algae and archaea. Targeting researchers and biotechnology professionals, it explores the foundational ecology of these partnerships, their profound influence on carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles, and their evolutionary history. The review further addresses the significant methodological challenges in studying these interactions, evaluates their applications in biotechnology and climate change mitigation, and compares their functions with the more familiar algal-bacterial systems. By integrating the latest research, this article aims to provide a comprehensive framework to guide future exploration and harness the potential of algae-archaea symbiosis for scientific and industrial advancement.

The Unseen Partners: Exploring the Diversity and Ecological Foundations of Algae-Archaea Symbiosis

The concept of the holobiont, which considers a host organism and its associated microbial communities as a functional unit, is reshaping our understanding of marine ecology. While algal-bacterial interactions have been extensively studied, the integral role of archaea within algal holobionts has remained a critical knowledge gap. This review synthesizes emerging evidence that archaea are consistent, specialized members of both macroalgal surface communities and the microalgal phycosphere. We explore the diversity of these algal-archaeal associations, their putative symbiotic functions, and their combined influence on biogeochemical cycling. Technological advances in metagenomics and culturing are now unveiling the hidden archaeal diversity within these niches, providing novel insights into the ecological and biotechnological significance of the algal-archaea holobiont.

Archaea, once believed to inhabit only extreme environments, are now recognized as ubiquitous and abundant in temperate marine systems [1] [2]. In the context of algal biology, where research has overwhelmingly focused on bacterial partners, archaea represent the overlooked component of the holobiont. The holobiont framework posits that the algal host and its entire associated microbiome—including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses—form a cohesive ecological and functional unit [3] [4]. The phycosphere, the region immediately surrounding an algal cell influenced by its exudates, serves as a key interface for metabolic exchange between the host and its associated microbes [5]. Despite their low relative abundance, archaea are increasingly implicated in the health, stability, and metabolic output of the algal holobiont [1] [6] [2]. Understanding the specific niches and functions of archaea, from the microscale phycosphere to the complex surface structures of macroalgae, is essential for a complete picture of marine primary production and biogeochemical cycling.

Diversity of Algal-Associated Archaea

Archaeal communities associated with algae are distinct from those in the surrounding seawater and are consistently dominated by specific lineages, though their composition varies between macroalgal and microalgal hosts.

Archaea on Macroalgal Surfaces

The macroalgal surface, or thallus, provides a nutrient-rich, oxygenated habitat for microbiota. Metagenomic studies have revealed that archaea are recurrent, though often minorit,y members of this epiphytic community. The table below summarizes the primary archaeal groups identified on various macroalgae.

Table 1: Key Archaeal Lineages Associated with Macroalgae

| Archaeal Group | Putative Function | Example Hosts | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrososphaeria (Marine Group I) | Ammonia oxidation, Nitrification | Ulva prolifera, Pyropia haitanensis | [1] [2] |

| Methanogenic Euryarchaeota(e.g., Methanomicrobiaceae, Methanosarcinaceae) | Methanogenesis, Carbon cycling | Sargassum spp., Ulva prolifera | [1] [2] |

| Marine Group II (Poseidoniales) | Dissolved organic matter cycling, Possible symbiosis | Ulva prolifera | [1] [2] |

| Bathyarchaeia, Lokiarchaeia | Putative hydrocarbon degradation, Other metabolisms | Ulva prolifera | [1] [2] |

| Nanoarchaeales, Woesearchaeales | Reduced-genome symbionts, Fermentative metabolisms | Epilithic macroalgae in the Gulf of Thailand | [1] [2] |

The dominance of Nitrososphaeria (formerly Thaumarchaeota) and methanogens points to a critical role for macroalgal-associated archaea in nitrogen and carbon transformation, respectively, within the holobiont [1] [2].

Archaea in the Microalgal Phycosphere

The phycosphere of microalgae is a dynamic zone of chemical interaction. Archaea in this environment are primarily represented by two major groups, which often show population-level correlations with phytoplankton dynamics.

Table 2: Dominant Archaea in the Microalgal Phycosphere

| Archaeal Group | Ecological Correlation | Putative Interaction | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Group I (MGI)(Nitrosopumilaceae) | Typically negative correlation with phytoplankton blooms | Competition for ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) | [2] |

| Marine Group II (MGII)(Poseidoniales) | Frequently positive correlation with phytoplankton blooms | Utilization of algal-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) | [1] [2] |

These contrasting correlations highlight the complex and nuanced nature of algal-archaeal interactions. While MGII may act as commensals or symbionts by consuming organic waste, MGI are likely competitors for a key nutrient, ammonium [2].

Methodologies for Studying the Algal-Archaea Holobiont

Research in this field is challenging due to the difficulty in cultivating many archaea and their relatively low abundance. A multi-pronged, cultivation-independent approach is essential.

Standardized Sampling and Metagenomic Analysis

A robust experimental workflow begins with careful sample collection. For macroalgae, this involves swabbing the thallus for epiphytes or processing tissue for endophytes, alongside collecting surrounding seawater and sediment controls [4] [7]. For microalgae, phycosphere water is filtered to capture associated microbes.

Subsequent DNA extraction and sequencing are foundational. The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (e.g., targeting V3-V4 regions with primers 341F/806R) is widely used for initial community profiling and identifying core microbial taxa [8] [7]. For deeper functional insights, shotgun metagenomics is employed. This involves sequencing all the DNA in a sample, followed by assembly into contigs and the binning of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) [4] [7]. This powerful approach allows for the genomic characterization of uncultivated archaea, revealing their metabolic potential. Furthermore, viromics—sequencing of virus-enriched fractions—is emerging as a crucial tool for understanding how viruses influence the holobiont's equilibrium by infecting archaeal and bacterial members [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Algal Holobiont Research

| Item / Kit Name | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleospin Soil Kit (MN) | Metagenomic DNA extraction from complex samples | DNA extraction from macroalgal swabs, sediment, and cell pellets [8] [7]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN) | Metagenomic DNA extraction, optimized for environmental samples | DNA extraction from water column and sediment filters [4]. |

| Primers 341F / 806R | Amplification of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene | Profiling prokaryotic (bacterial and archaeal) community structure [8] [4]. |

| Illustra GenomiPhi V3 DNA Amplification Kit | Whole-genome amplification of low-biomass viral DNA | Preparation of virome sequencing libraries from concentrated viral particles [4]. |

| PICRUSt2 / Tax4Fun2 | Bioinformatics software for predicting metagenomic functions | Inferring the functional potential of a microbial community from 16S rRNA amplicon data [8]. |

| a-Hydroxymetoprolol | a-Hydroxymetoprolol, CAS:56392-16-6, MF:C15H25NO4, MW:283.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE1 | 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE1, CAS:22973-19-9, MF:C20H32O5, MW:352.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Ecological and Biotechnological Significance

Role in Biogeochemical Cycles

The algal-archaea holobiont is a key node in global nutrient cycles. Nitrososphaeria are primary drivers of nitrification in marine systems, converting ammonia to nitrite, a process critical to the nitrogen cycle that can also compete with the algal host for ammonium [1] [2]. Conversely, methanogenic Euryarchaeota perform methanogenesis, influencing the carbon cycle by producing the potent greenhouse gas methane from algal biomass decomposition [1] [9]. Their activity is particularly relevant in the context of green tides and algal bloom decay. The presence of other lineages like Bathyarchaeia and Woesearchaeales suggests a wider, yet uncharacterized, involvement in carbon and hydrogen cycling within the holobiont [1] [2].

Biotechnological Applications

Understanding these symbiotic relationships opens doors to novel applications. Beneficial archaea can be used as probiotics in algal cultivation to enhance biomass accumulation and reduce production costs [1] [2]. Furthermore, methanogenic archaea are central to the anaerobic digestion of residual algal biomass for biogas production, improving the sustainability of algal biorefineries [1] [9]. The unique enzymes and secondary metabolites produced by archaea also have potential in biomass processing for cell disruption and the harvesting of algal cells [1] [2].

The definition of the algal holobiont is incomplete without the inclusion of archaea. Evidence now firmly establishes that specific archaeal lineages are consistent, functionally engaged partners in both macroalgal and microalgal systems, influencing host fitness and global biogeochemical fluxes. Future research must prioritize overcoming the significant cultivation bottleneck to establish model co-culture systems for hypothesis testing [1] [2]. There is also a pressing need for multi-omics studies that integrate metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics to move from genetic potential to actual function within the holobiont [6]. Finally, standardized methodologies and a greater focus on underrepresented algal species and geographical regions are essential to build a comprehensive, global understanding of the algal-archaea holobiont [6]. Embracing this complexity will be key to unlocking both fundamental ecological insights and pioneering biotechnological innovations.

Archaea, once believed to inhabit only extreme environments, are now recognized as ubiquitous and ecologically significant components of diverse ecosystems, including those dominated by algae [1] [10]. While algal-bacterial interactions have been extensively studied, understanding of algal-archaeal associations remains limited despite their potential importance in global biogeochemical cycles and algal physiology [1] [11]. This whitepaper synthesizes current knowledge on three major archaeal lineages frequently associated with algal hosts: the ammonia-oxidizing Nitrososphaeria (formerly Thaumarchaeota), the heterotrophic Marine Group II (MGII) within Euryarchaeota, and various methanogenic Euryarchaeota. These associations represent a frontier in microbial ecology with implications for understanding symbiotic relationships, nutrient cycling in aquatic environments, and developing algal biotechnology applications.

Major Archaeal Lineages in Algal Associations

Nitrososphaeria

Nitrososphaeria, particularly members of the family Nitrosopumilaceae, are frequently identified in association with diverse algal hosts [1]. These archaea are chemolithoautotrophic ammonia-oxidizers that play crucial roles in nitrogen cycling by converting ammonia to nitrite. Their co-occurrence with algae suggests a potential symbiotic relationship where algae provide ammonia from their metabolic waste, while Nitrososphaeria generate nitrite that can be utilized by other microorganisms or further processed in the nitrogen cycle [1].

Table 1: Diversity and Distribution of Major Archaeal Lineages in Algal Associations

| Archaeal Lineage | Major Metabolic Function | Algal Hosts/Environments | Representative Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrososphaeria | Ammonia oxidation | Macroalgae (Ulva prolifera, Pyropia haitanensis), Microalgae (diatoms) | Nitrosopumilaceae, Nitrososphaeraceae |

| Marine Group II (MGII) | Heterotrophic, protein degradation | Microalgae (Phaeocystis, Chaetoceros, Heterosigma, Micromonas) | Uncultured MGII subgroups |

| Methanogenic Euryarchaeota | Methanogenesis (methyl-reducing pathway) | Hypersaline environments with algae | Methanomicrobiaceae, Methanosarcinaceae, Methanococcaceae, "Methanonatronarchaeia" |

Marine Group II (MGII)

Marine Group II represents one of the most prevalent archaeal groups in the ocean, with numerous studies reporting their consistent co-occurrence with phytoplankton blooms [1]. MGII are heterotrophic archaea thought to primarily degrade proteins and are abundant in the photic zone where algal productivity is high [12]. Their phylogenetic diversification has been linked to major geological events, with estimates suggesting they emerged near the Great Oxidation Event [12]. Their recurrent associations with diverse microalgae, including Phaeocystis, Chaetoceros, Heterosigma, and Micromonas pusilla, suggest these archaea may play important roles in processing organic matter derived from algal photosynthesis [1].

Methanogenic Euryarchaeota

Methanogenic archaea belonging to the Euryarchaeota phylum have been identified in association with macroalgal hosts such as Sargassum and Ulva prolifera [1]. These archaea produce methane through various pathways, including the methyl-reducing pathway observed in newly discovered extremophilic lineages [13]. In hypersaline environments where algae exist, extremely halophilic methyl-reducing methanogens such as the recently discovered "Methanonatronarchaeia" have been identified [13]. This deep phylogenetic lineage represents a class-level taxon most closely related to Halobacteria and employs a "salt-in" osmoprotection strategy, accumulating high intracellular potassium concentrations rather than organic osmolytes [13].

Methodological Approaches for Studying Algal-Archaea Associations

Molecular Detection and Community Analysis

Protocol 1: 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing for Archaeal Diversity Assessment

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Filter water or sediment samples through 0.22 µm membranes. For macroalgal epiphytes, swab algal surfaces or grind tissue samples. Extract DNA using commercial kits (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit) with bead beating to ensure lysis of archaeal cells [14] [15].

- Library Preparation: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene V4 hypervariable region using archaea-specific primers (e.g., Arch524F -

GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAAand Arch958R -GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) [14]. Alternatively, use universal prokaryotic primers (515F/806R) if targeting both bacteria and archaea, noting that universal primers may under-detect some archaeal lineages [1] [11]. - Sequencing and Processing: Sequence on Illumina platforms (e.g., HiSeq2000). Process raw reads using DADA2 in QIIME2 for denoising, chimera removal, and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) calling [14].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs against curated archaeal databases (Silva v132, GTDB). For algal chloroplast sequences identified in the dataset, classify using PhytoRef database to identify algal taxa [14].

Protocol 2: Co-occurrence Network Analysis

- Data Preparation: Create abundance tables with bacterial (genus-level) and algal (ASV-level) counts. Filter low-prevalence organisms present in <10% of samples [14].

- Correlation Analysis: Use FastSpar (SparCC algorithm) to compute correlations between all ASVs. Generate correlation and p-value matrices with bootstrap procedures [14].

- Network Construction: Build undirected weighted networks in R using igraph package. Apply significance (p < 0.05) and correlation thresholds (r > 0.5-0.6). Cluster networks using MCL algorithm (inflation=2.0) to identify modules of co-occurring taxa [14].

- Network Analysis: Calculate node degree, centrality metrics, and identify keystone species. Visualize networks in Cytoscape [14].

Cultivation Approaches

Protocol 3: Enrichment and Isolation of Extremely Halophilic Methyl-Reducing Methanogens

- Sample Stimulation: Inoculate sediment slurries from hypersaline lakes (soda or salt lakes) into synthetic media with 4 M total Na+. For soda lakes, adjust pH to 9.5-10; for neutral salt lakes, maintain pH ~7. Supplement with methylotrophic substrates (MeOH or trimethylamine) combined with formate or H₂. Incubate at elevated temperatures (48-60°C) [13].

- Methane Detection: Monitor methane production via gas chromatography. Compare methane yield in methyl-compound + formate/Hâ‚‚ conditions versus single substrates [13].

- Purification: Perform sequential 1:100 dilutions in synthetic media. Add colloidal FeSₓ·nH₂O (for soda lakes) or sterilized sediments (for salt lakes) as growth enhancers. Filter through 0.45 µm filters and apply antibiotic treatments to obtain pure cultures [13].

- Characterization: Analyze marker genes (16S rRNA, mcrA) for phylogenetic placement. Examine cell morphology via electron microscopy. Test salt dependence, osmolyte strategy, and cytochrome content [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Algal-Archaeal Associations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Archaea-specific primers (Arch524F/Arch958R) | Target 16S rRNA gene for amplicon sequencing | Selective amplification of archaeal communities; avoids bacterial dominance [14] |

| PhytoRef database | Taxonomic classification of algal chloroplast 16S sequences | Identification of microalgal partners in co-occurrence networks [14] |

| Synthetic hypersaline media (4 M Na+) | Cultivation of extreme halophiles | Enrichment of "Methanonatronarchaeia" and other halophilic archaea [13] |

| Methylotrophic substrates (MeOH, TMA) + electron donors (formate, Hâ‚‚) | Selective for methyl-reducing methanogens | Stimulating methane production under methyl-reducing conditions [13] |

| Colloidal FeSₓ·nH₂O | Growth enhancer for syntrophic cultures | Improving cultivation success of fastidious archaea from soda lakes [13] |

| BOC-L-phenylalanine-d5 | BOC-L-phenylalanine-d5, CAS:121695-40-7, MF:C14H19NO4, MW:270.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine 7-oxide | 1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine 7-Oxide|CAS 55052-24-9 | 1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine 7-Oxide is a key synthon for 7-azaindole functionalization in medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Interactions

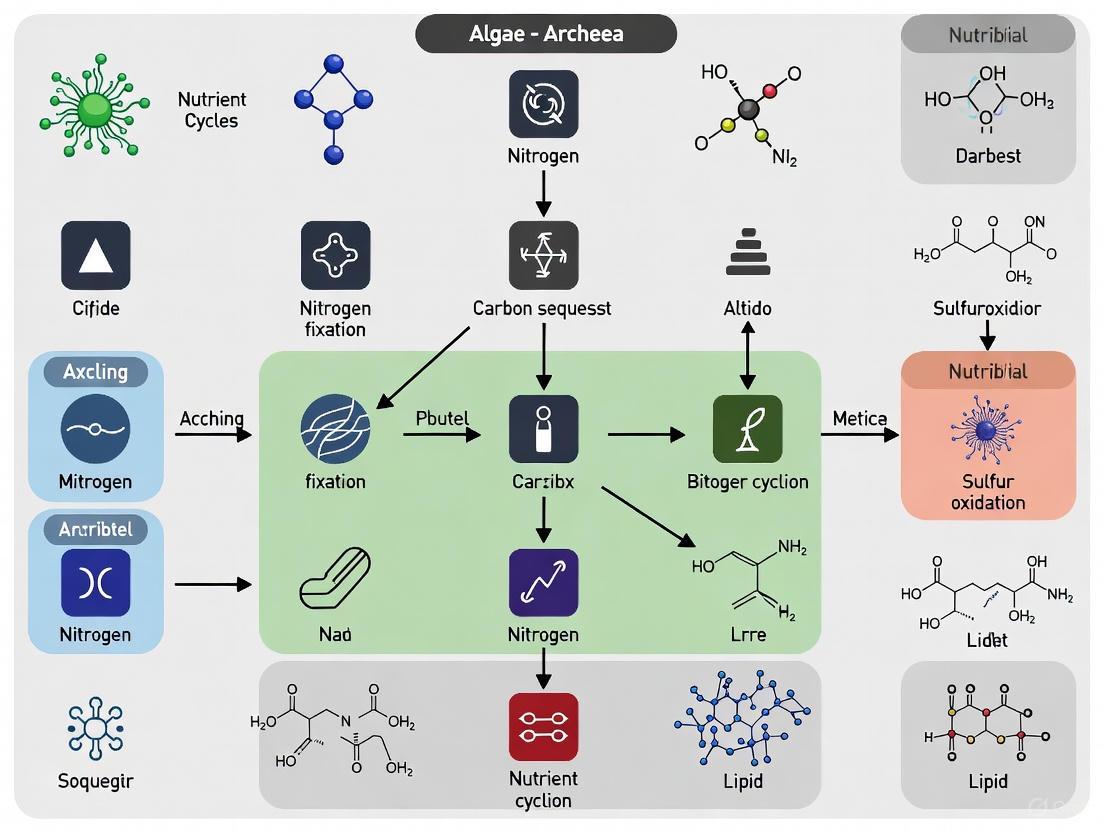

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for studying algal-archaeal associations, combining molecular and cultivation-based approaches.

Figure 2: Putative metabolic relationships between algae and major archaeal lineages.

The associations between algae and archaeal lineages represent a significant yet underexplored dimension of microbial ecology. Nitrososphaeria, Marine Group II, and methanogenic Euryarchaeota frequently co-occur with diverse algal hosts across aquatic ecosystems, where they likely participate in interconnected biogeochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements [1]. Methodological advances in molecular detection, co-occurrence network analysis, and specialized cultivation techniques are progressively revealing the diversity and functional roles of these archaeal symbionts [13] [14]. Future research should focus on establishing robust co-culture models, applying metagenomics and metatranscriptomics to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying these associations, and exploring how these interactions influence broader ecosystem processes and respond to environmental change [1]. Understanding these relationships has dual significance for both advancing fundamental knowledge of microbial symbioses and developing practical applications in algal biotechnology, climate science, and aquatic ecosystem management.

This technical review synthesizes current evidence on the co-occurrence patterns between Marine Group I (MGI) and Marine Group II (MGII) archaea and diverse phytoplankton lineages. Growing metagenomic and co-occurrence network data reveal these archaea as consistent partners in the phycosphere, forming association patterns ranging from generalist to specialist interactions. These structured relationships are mediated through specific molecular mechanisms, including vitamin synthesis, nutrient remineralization, and chemotaxis. The elucidation of these patterns is critical for modeling their collective impact on global biogeochemical cycles, particularly carbon and nitrogen fluxes, and for harnessing these interactions in biotechnological applications.

Marine phytoplankton form the foundation of aquatic food webs, accounting for approximately 50% of global net primary production [16]. These microscopic algae do not exist in isolation but within complex microbial communities where interactions with archaea have remained a critically understudied domain despite their ecological significance [1]. The discovery that mesophilic archaea, particularly Marine Group I (Thaumarchaeota) and Marine Group II (Halobacteriaceae), inhabit diverse oceanic waters has stimulated research into their potential symbiotic relationships with phytoplankton [1].

The phycosphere—the microenvironment immediately surrounding phytoplankton cells where metabolite concentrations are elevated—serves as the primary interface for these interactions [17]. Within this niche, algae and archaea likely engage in complex metabolic exchanges that influence global biogeochemical cycles, including carbon fixation, nitrogen transformation, and organic matter remineralization [1] [18]. Understanding the specific co-occurrence patterns between Marine Groups I/II and phytoplankton provides a foundation for deciphering the underlying mechanisms of these ecologically vital partnerships.

Quantitative Evidence of Association Patterns

Empirical evidence from global oceanographic surveys has begun to quantify the specific associations between Marine Group I/II archaea and various phytoplankton taxa, revealing distinct patterns of interaction.

Table 1: Documented Co-occurrence Patterns between Marine Group Archaea and Phytoplankton

| Archaeal Group | Phytoplankton Partner | Association Type | Ecological Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Group II | Dinophyta, Chlorophyta, Bacillariophyta | Generalist Co-occurrence | Global Ocean Survey (Tara Oceans) | [1] |

| Marine Group II | Phaeocystis, Chaetoceros, Heterosigma | Positive Correlation | San Pedro Ocean Time-series | [1] |

| Marine Group II | Diatoms, Pseudo-nitzschia, Chaetoceros | Recurring Association | Offshore California, USA | [1] |

| Marine Group II | Micromonas pusilla | Specific Partnership | Coastal California | [1] |

| Marine Group I & II | Bathycoccus prasinos | Co-occurrence | San Pedro Ocean Time-series | [1] |

| Marine Group I | Macroalgae (e.g., Ulva prolifera) | Epiphytic Presence | Coastal Qingdao, China | [1] |

Table 2: Genomic Functional Enrichment in Phytoplankton-Associated Archaea

| Functional Category | Specific Genes/Functions | Potential Benefit to Phytoplankton | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin Synthesis | Vitamin B12, B7 biosynthesis | Provision of essential growth cofactors | Genomic Prediction [17] |

| Nutrient Remineralization | Ammonia oxidation (MGI), organic matter hydrolysis | Nitrogen cycling, nutrient solubilization | [1] [19] |

| Metabolite Exchange | Transporter genes for organic compounds | Uptake of phytoplankton-derived DOC | [17] |

| Environmental Sensing | Chemotaxis and motility genes | Colonization of the phycosphere | [17] |

| Antimicrobial Production | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis | Protection against algal pathogens | [17] |

Methodologies for Characterizing Interactions

Field Sampling and Environmental DNA Sequencing

Sample Collection: Integrated water samples are typically collected using Niskin bottles deployed on CTD rosettes, capturing various depths through the photic zone. For phytoplankton-archaea associations, a large volume of water (500-1000 mL) is filtered sequentially through 3.0 μm and 0.22 μm polyethersulfone (PES) membranes to capture particle-associated (including phytoplankton) and free-living microorganisms, respectively [16].

DNA Extraction and Amplification: Total environmental DNA is extracted from filters using commercial kits such as the FastDNA Soil Genome DNA Extraction Kit (MP Bio) [16]. For phytoplankton community analysis, the plastid 23S rRNA gene is targeted using primers p23SrVf1 and p23SrVr1, providing higher phylogenetic resolution than 16S rRNA for algal lineages [16]. For associated archaea, the 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 regions are amplified using archaea-specific primers (e.g., 341F/806R) [8].

Sequencing and Bioinformatics: Amplicons are sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform. Processing involves quality filtering, denoising (e.g., using DADA2), and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) calling in QIIME 2. Taxonomic assignment is performed against curated databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) using BLAST [16] [8].

Co-occurrence Network Analysis

Construction: ASV tables are filtered to retain only taxa present in more than three samples. Pairwise correlations (e.g., Spearman's rank) are computed, retaining only robust correlations (e.g., |R| > 0.6, FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.05) to construct a sparse network [16] [20].

Topological Analysis: The resulting network is visualized in Gephi 0.9.2. Key metrics calculated include:

- Modularity: Measures how compartmentalized the network is.

- Average Degree: Average number of connections per node.

- Average Path Length: Average shortest distance between nodes.

- Vulnerability: Measures network sensitivity to node removal [20].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for co-occurrence network analysis.

Laboratory Model System Development

Phytoplankton Isolation: Single phytoplankton cells are isolated from plankton tows using micromanipulation or flow cytometry and established in culture with sterile medium [17].

Longitudinal Microbiome Tracking: The bacterial and archaeal communities associated with each phytoplankton strain are characterized via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing at multiple time points (e.g., 7, 10, 20, 40, 200, and 400 days) to distinguish specialist associates (present in 1-2 phytoplankton strains) from generalist associates (present in ≥3 strains) and transients [17].

Metagenomic Sequencing: Shotgun metagenomics on the associated community identifies functional genes and pathways underlying the symbiotic relationship, such as those involved in vitamin synthesis, nutrient cycling, and chemotaxis [17].

Mechanisms and Ecological Consequences

Metabolic Interdependence and Signaling

The co-occurrence patterns observed between Marine Group I/II archaea and phytoplankton are underpinned by specific metabolic interactions. Marine Group I (Nitrososphaeria) are capable of ammonia oxidation, converting ammonia to nitrite, thereby playing a crucial role in nitrogen cycling within the phycosphere that may benefit phytoplankton nutrition [1] [19]. Genomic evidence suggests that generalist and specialist archaeal associates are enriched in genes for vitamin B12 and B7 synthesis, potentially providing essential growth cofactors to algal partners [17].

Diagram 2: Putative metabolite exchange in the phycosphere.

Impact on Biogeochemical Cycles

The structured interactions between phytoplankton and archaea significantly influence global biogeochemical processes. Phytoplankton-archaea associations in the East China Sea demonstrate that these partnerships are sensitive to nutrient regimes, with deterministic processes governing community assembly in both nutrient-rich and oligotrophic waters [16]. The coupling of carbon and nitrogen cycles is evident, where phytoplankton-derived organic carbon fuels archaeal metabolism, while archaeal ammonia oxidation and nutrient remineralization enhance phytoplankton growth and primary production [1] [19]. Furthermore, the co-occurrence of methanogenic Euryarchaeota with macroalgae suggests a potential link between algal productivity and methane production, potentially contributing to the oceanic methane paradox [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example / Model | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Filtration System | Whatman GF/F glass fiber filters (~0.7 μm), 0.22 μm PES membranes | Size-fractionated concentration of microbial cells from water samples. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | FastDNA Soil Kit (MP Bio), Nucleospin Soil Kit (MN) | Efficient lysis and purification of genomic DNA from environmental samples. |

| PCR Primers (Archaea) | 341F (5'-GCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') / 806R | Amplification of 16S rRNA V3-V4 regions for archaeal community analysis. |

| PCR Primers (Phytoplankton) | p23SrVf1 / p23SrVr1 | Targeting plastid 23S rRNA for high-resolution phytoplankton taxonomy. |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina MiSeq PE300 | High-throughput amplicon sequencing for community profiling. |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | QIIME 2, DADA2 | Data processing, denoising, and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) calling. |

| Network Analysis Software | Gephi 0.9.2 | Visualization and topological analysis of co-occurrence networks. |

| Statistical Environment | R package "vegan" | Calculation of diversity indices and multivariate statistical analysis. |

| Methyl pyrimidine-2-carboxylate | Methyl pyrimidine-2-carboxylate, CAS:34253-03-7, MF:C6H6N2O2, MW:138.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Methylpiperazine-d4 | N-Methylpiperazine-3,3,5,5-D4 Deuterated Reagent | N-Methylpiperazine-3,3,5,5-D4 (C5H8D4N2). A deuterated building block for organic synthesis and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Evidence from global marine ecosystems consistently demonstrates that Marine Group I and II archaea form non-random, metabolically structured co-occurrence patterns with diverse phytoplankton hosts. These interactions are governed by a complex interplay of deterministic environmental filtering, metabolic interdependence, and stochastic processes. Future research must prioritize the development of robust laboratory co-culture models to move beyond correlation and definitively establish causal mechanisms. Furthermore, integrating metagenomic insights with metatranscriptomic and metabolomic approaches will reveal the dynamic functional landscape of these associations. A precise understanding of these patterns is paramount for predicting ecosystem responses to global change and for harnessing these partnerships in sustainable biotechnological applications.

The evolutionary history of marine archaea is inextricably linked to the biogeochemical development of Earth's oceans and represents a critical, yet understudied, component of the planet's microbial ecosystems. While bacterial evolution has received considerable scientific attention, the deep-time diversification of marine archaea remains less clearly defined, particularly within the context of algal-archaeal symbiotic relationships that underpin key marine biogeochemical cycles. The discovery that mesophilic archaea are widespread in temperate and oxygenated marine waters, rather than restricted to extreme environments, has fundamentally shifted our understanding of their ecological significance [1] [2]. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of marine archaeal diversification through deep time, examines the methodological frameworks enabling these discoveries, and explores the profound implications for understanding contemporary algae-archaea interactions in biogeochemical cycling. By reconstructing the timeline of marine archaeal evolution, we can establish an evolutionary context for interpreting modern symbiotic relationships and their roles in global nutrient cycles, thereby providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for integrating archaeal evolution into broader marine ecological and biogeochemical models.

Deep-Time Diversification Timeline of Marine Archaea

Major Geological Events and Marine Archaeal Diversification

The colonization of ocean environments by major archaeal lineages spans billions of years, with diversification events closely correlated with major oxygenation events in Earth's history. Advanced molecular dating analyses using benchmarked multi-domain phylogenetic trees have revealed that marine archaeal clades diversified across distinct geological eras, responding to fundamental shifts in ocean chemistry and the emergence of new ecological niches [21] [22]. These analyses employ Bayesian relaxed molecular clock methods with geochemical evidence as temporal calibrations, including the age of liquid water (≈4400 My) and the most ancient record of biogenic methane (≈3460 My) as maximum and minimum priors for domain-level calibrations [21] [22]. The timeline reveals a pattern of sequential diversification, with different archaeal groups emerging in response to specific planetary transitions.

Table 1: Marine Archaeal Diversification in Relation to Geological Events

| Geological Era/Event | Time (Million years ago) | Marine Archaeal Groups Diversifying | Environmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Oxidation Event (GOE) | ≈2479-2196 Ma | SAR202, Marine Group II (MGII) | Increased oxygen but microaerophilic conditions; oxygen oases in pre-GOE Earth [21] [22] |

| Mid-Proterozoic | ≈2196-800 Ma | SAR324, Ca. Marinimicrobia | Continued microaerophilic conditions throughout Mid-Proterozoic [21] [22] |

| Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (NOE) | 800-400 Ma | Marine Group I (MGI) | Increase of oxygen and nutrients in ocean; diversification of eukaryotic algae [21] [22] |

| Phanerozoic Oxidation Event | After 450-400 Ma | (Phototrophic bacterial clades) | Oxygen concentrations reached modern levels [21] [22] |

Key Marine Archaeal Groups and Their Evolutionary Significance

The earliest diversifying marine archaeal clades include Marine Group II (MGII) of the phylum Euryarchaeota, which emerged near the Great Oxidation Event [21] [22]. The ancient pre-GOE origin of SAR202 (2479 My, 95% CI 2465–2492 My) suggests this clade emerged during proposed oxygen oases in pre-GOE Earth, consistent with their broadly distributed aerobic capabilities [21] [22]. The diversification of Marine Group I (MGI), now classified as Nitrososphaeria, occurred later during the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (0.8–0.4 Ga), concomitant with an overall increase of oxygen and nutrients in the ocean as well as the diversification of eukaryotic algae [21] [22]. This temporal coincidence suggests a potential evolutionary linkage between the diversification of heterotrophic microbes and the emergence of large eukaryotic phytoplankton, which would have significantly altered the marine organic carbon cycle.

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Marine Archaeal Groups

| Archaeal Group | Phylogenetic Classification | Diversification Timeline | Metabolic Features | Contemporary Ecological Niches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Group I (MGI) | Nitrososphaeria (formerly Thaumarchaeota) | Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (800-400 Ma) [21] [22] | Ammonia oxidation, carbon fixation [1] [2] | Oxygenated waters; competition with phytoplankton for ammonium [2] |

| Marine Group II (MGII) | Poseidoniales (Euryarchaeota) | Near Great Oxidation Event (≈2479-2196 Ma) [21] [22] | Heterotrophic, proteorhododpsin-based photoheterotrophy [1] | Surface to mesopelagic waters; association with algal blooms [1] [2] |

| Methanogenic Euryarchaeota | Various families (Methanosarcinaceae, Methanococcaceae, etc.) | Not specified in studies | Methanogenesis | Macroalgal surfaces; anaerobic microenvironments [1] [2] |

| Bathyarchaeia | Bathyarchaeia | Not specified in studies | Heterotrophic, potential for hydrocarbon degradation | Deep sediments; associated with green tides [1] |

Methodological Frameworks for Studying Archaeal Evolution

Molecular Dating and Phylogenetic Analysis

Reconstructing the deep-time diversification of marine archaea requires sophisticated molecular dating approaches that overcome limitations of the microbial fossil record. The most advanced methodologies involve constructing multi-domain phylogenetic trees using benchmarked sets of marker genes that are congruent for inter-domain phylogenetic reconstruction [21] [22]. These analyses typically employ:

- Gene Selection: Curated sets of universally conserved, single-copy marker genes that avoid horizontal gene transfer issues and provide robust phylogenetic signals across domains.

- Sequence Alignment and Tree Construction: Use of maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference methods with comprehensive model testing to account for site-specific and lineage-specific rate variation.

- Divergence Time Estimation: Implementation of relaxed molecular clock models in Bayesian frameworks (e.g., MCMCTree, BEAST) that accommodate rate variation across lineages.

- Calibration Strategy: Utilization of multiple geochemical and paleontological calibration points, including the Great Oxidation Event (2320 Ma) to constrain aerobic lineages, and evidence of liquid water (4400 Ma) and earliest life (3460 Ma) for root priors [21] [22].

These methodological approaches allow for simultaneous dating of bacterial and archaeal lineages, enabling direct comparison of evolutionary timelines across domains and providing a comprehensive view of microbial diversification in the ocean through deep time.

Experimental Models and Cultivation Challenges

A significant limitation in advancing our understanding of algae-archaea interactions is the challenge of cultivating novel archaeal representatives. As noted in current research, "It is essential to isolate and culture species from those uncultured archaeal lineages (such as Marine Group II and III) to establish algae-archaea co-culture models for better understanding their physiology and ecological roles" [1] [2]. The successful culturing of novel archaeal representatives remains limited despite rapid methodological and technological advances, creating a critical bottleneck in functional studies [1] [2]. Current experimental approaches include:

- Co-culture Systems: Development of simplified model systems containing algae and archaea to investigate symbiotic interactions under controlled conditions.

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Analysis of uncultured archaeal diversity through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics from environmental samples and algal holobionts.

- Stable Isotope Probing: Tracking nutrient flows between algal and archaeal partners using 13C, 15N, and other isotopic tracers.

- Single-cell Genomics: Bypassing cultivation requirements through genomic analysis of individual archaeal cells sorted from environmental samples or algal associations.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Studying Marine Archaeal Evolution

Algae-Archaea Symbiosis in Biogeochemical Cycles

Evolutionary Context of Modern Symbiotic Relationships

The deep-time diversification of marine archaea establishes an evolutionary framework for interpreting contemporary algae-archaea interactions and their roles in biogeochemical cycling. The coincidence between the diversification of heterotrophic archaeal clades and the emergence of large eukaryotic phytoplankton in the Neoproterozoic suggests an ancient evolutionary foundation for modern symbiotic relationships [21] [22]. Current research indicates that archaea are involved in the cycling of essential elements such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, as well as other trace metals, with their complex interactions potentially influencing atmospheric pools of greenhouse gases such as CO2 and CH4 through carbon fixation and methanogenesis [1] [2]. The evolutionary timing of these diversification events suggests that marine archaea have been integral components of marine biogeochemical cycles since early in Earth history, with their metabolic capabilities evolving in response to, and influencing, planetary-scale environmental transitions.

Specific Algal-Archaeal Associations

Modern marine ecosystems reveal diverse associations between archaea and algae that likely have deep evolutionary roots. Marine Group I (MGI) and Marine Group II (MGII) are the most common archaeal groups correlated with microalgae, with MGI typically showing negative correlations with phytoplankton communities due to competition for ammonium, though positive correlations have also been observed in some studies [2]. Macroalgal surfaces provide ideal habitats for microbiota, hosting archaeal communities dominated by Nitrososphaeria and methanogenic Euryarchaeota, though these archaeal taxa are often overlooked in microbiome studies due to their relatively low abundance compared to bacterial associates [1] [2]. Specific associations include:

- Epiphytic Archaea on Macroalgae: Nitrososphaeria, Methanomicrobiaceae, Methanosarcinaceae, and Methanococcaceae found associated with Sargassum, Ulva prolifera, and other macroalgae [1] [2].

- Phycosphere Archaea: MGI and MGII archaea detected in the microbial communities surrounding microalgal cells, particularly during algal blooms [2].

- Extremophile Associations: Bathyarchaeia, Lokiarchaeia, and Woesearchaeales associated with green tides and epilithic macroalgae in specialized environments [1].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Algae-Archaea Interactions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dating Tools | MCMCTree, BEAST2, PhyloBayes | Bayesian molecular clock analysis for divergence time estimation | Requires appropriate calibration priors and model testing [21] [22] |

| Phylogenetic Markers | Concatenated universal single-copy genes (e.g., ribosomal proteins) | Multi-domain phylogenetic reconstruction | Must be congruent across domains; benchmarked sets reduce artifacts [21] [22] |

| Cultivation Media | Defined mineral media with algal exudates | Enrichment and isolation of algal-associated archaea | Must simulate phycosphere conditions; often requires long incubation [1] [2] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | 13C-bicarbonate, 15N-ammonium, 18O-water | Tracking nutrient fluxes in algae-archaea symbiosis | Can be combined with NanoSIMS for spatial resolution [1] |

| Metagenomic Tools | 16S rRNA archaeal primers, shotgun sequencing | Characterization of uncultured archaeal diversity | Primer bias remains a challenge for archaeal community profiling [1] [2] |

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Methodological Limitations and Needs

Despite significant advances in understanding marine archaeal diversification, substantial research gaps remain. The field is hampered by the "challenge of isolating archaea," with successful culturing of novel archaeal representatives remaining limited despite rapid methodological and technological advances [1] [2]. This cultivation bottleneck fundamentally constrains our ability to functionally characterize algal-archaeal interactions and validate evolutionary hypotheses generated from genomic data. Additional methodological challenges include:

- Primer Bias: Archaeal communities are frequently underrepresented in microbiome studies due to primer mismatches and amplification biases in 16S rRNA protocols.

- Standardization Needs: Lack of standardized protocols in microbiome research creates challenges for comparative analyses across studies and ecosystems [6].

- Temporal Dynamics: Most studies provide only snapshot views of archaeal diversity, with limited longitudinal data tracking community changes over time or in response to environmental perturbations [6].

- Geographic Biases: Significant under-representation of certain geographical areas in algal microbiome research, particularly from underdeveloped regions and the Southern Hemisphere, skews our understanding of global archaeal diversity and evolution [6].

Integrative Research Opportunities

Future research directions should prioritize integrative approaches that connect deep-time evolutionary patterns with contemporary ecological function. Promising avenues include:

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics to link archaeal evolutionary history with contemporary functional roles in algal holobionts.

- Paleogenomic Approaches: Applying evolutionary constraints inferred from deep-time diversification to predict functional interactions in modern ecosystems.

- Experimental Evolution: Using laboratory systems to test hypotheses about the selective pressures that shaped archaeal diversification in response to historical Earth system transitions.

- Biotechnological Applications: Leveraging knowledge of ancient symbiotic relationships to develop novel applications in bioenergy, bioremediation, and sustainable biotechnology [1] [2] [23].

Figure 2: Feedback Relationships in Archaeal Evolution and Biogeochemistry

The deep-time diversification of marine archaea represents a critical evolutionary narrative that spans more than 2.2 billion years of Earth history, with major groups colonizing ocean environments during distinct geological eras characterized by fundamental shifts in ocean chemistry and biological complexity. The timeline of marine archaeal evolution, from the emergence of groups like Marine Group II near the Great Oxidation Event to the diversification of Marine Group I alongside eukaryotic algae during the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event, provides an essential evolutionary context for interpreting modern algae-archaea symbiotic relationships and their roles in biogeochemical cycles. Reconstructing this evolutionary history requires sophisticated methodological approaches that overcome significant challenges, particularly the difficulty of cultivating archaeal representatives and the limited fossil record. Future research that integrates deep-time evolutionary patterns with contemporary functional ecology, leveraging multi-omics approaches and addressing critical knowledge gaps in archaeal biology, will substantially advance our understanding of these fundamental components of marine ecosystems and their responses to ongoing environmental change. For researchers investigating algal-archaeal interactions and biogeochemical cycles, this evolutionary perspective provides an essential framework for interpreting modern ecological patterns and predicting ecosystem responses to anthropogenic perturbations.

Within the framework of biogeochemical cycles research, symbiotic relationships between algae and archaea represent a frontier in understanding aquatic ecosystem dynamics. Compared to the well-documented interactions between algae and bacteria, the putative symbiotic mechanisms between algae and archaea remain significantly underexplored, presenting a critical knowledge gap in environmental microbiology [1]. These interactions are now recognized as potent drivers of global carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles, influencing processes from carbon sequestration to methane production [1]. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the core mechanistic themes governing these relationships: nutrient exchange, molecular signaling, and horizontal gene transfer (HGT). By integrating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual schematics, this review provides researchers with a foundational toolkit for advancing research into algae-archaea symbiosis and its broader ecological implications.

Nutrient Exchange and Metabolic Interdependence

Nutrient exchange forms the bedrock of algal-archaeal symbiosis, creating a mutualistic framework that enhances the metabolic capabilities and environmental resilience of both partners. This exchange is primarily centered on the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, and essential micronutrients.

Carbon and Oxygen Cycling: The foundational exchange involves gases critical to aerobic and anaerobic metabolism. Algae, as primary producers, fix atmospheric COâ‚‚ into organic carbon through photosynthesis, simultaneously releasing Oâ‚‚ [24] [25]. This oxygen can support aerobic ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), which are frequently associated with macroalgal surfaces [1]. In return, archaeal respiratory COâ‚‚ production can be re-assimilated by algae, creating a efficient closed-loop carbon cycle [26]. In anaerobic environments, methanogenic archaea perform the critical terminal step in organic matter mineralization, converting algae-derived organic compounds into methane (CHâ‚„) [9].

Nitrogen Metabolism: Ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), particularly those from the Nitrososphaeria class (formerly Thaumarchaeota), are frequently detected in algal microbiomes [1]. They provide a vital service to the algal host by oxidizing ammonia to nitrite, a more readily assimilable nitrogen form. This process is crucial in nutrient-rich environments and for algae with high nitrogen demands [1] [9]. Genomic evidence suggests that some algae may have acquired genes related to nitrogen metabolism via HGT from prokaryotic donors, potentially enhancing their metabolic versatility [27].

Micronutrient Exchange: Archaea can enhance the bioavailability of essential trace metals and cofactors. For instance, some bacteria and potentially archaea release siderophores to overcome iron uptake limitations for their algal hosts [28]. Furthermore, the synthesis and exchange of vitamins, particularly B12, is a classic currency of microbial symbiosis. While more commonly documented in bacterial partners, the principle likely extends to archaea, given the auxotrophy of many algal species for this vitamin [28].

Table 1: Documented and Putative Nutrient Exchanges in Algae-Archaea Symbiosis

| Nutrient | Direction (Algae → Archaea) | Direction (Archaea → Algae) | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) [1] | COâ‚‚ from respiration [26] | Fuels heterotrophic archaea; feeds algal photosynthesis |

| Oxygen | Oâ‚‚ from photosynthesis [24] | - | Supports aerobic ammonia oxidation by AOA |

| Nitrogen | Ammonia (NH₃) from algal organic matter decomposition [1] | Nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») from archaeal ammonia oxidation [1] | Algae provide substrate for AOA; AOA supply bioavailable nitrogen |

| Vitamins | - | Cobalamin (B12) (putative) [28] | Supports growth of B12-auxotrophic algae |

| Trace Metals | - | Increased iron bioavailability via siderophores (putative) [28] | Overcomes algal limitation for essential micronutrients |

Molecular Signaling and Communication

Interkingdom signaling between algae and archaea coordinates symbiotic behaviors, including attachment, metabolic integration, and defense. These communications are mediated through small molecules and signal transduction pathways that influence gene expression and physiological responses in both partners.

Quorum Sensing (QS): While best characterized in bacteria, QS is a ubiquitous microbial language. Prokaryotes use autoinducer molecules, such as acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), to sense population density [25]. Evidence from algal-bacterial systems shows that algae can perceive and respond to these prokaryotic signals. For instance, exposure to AHLs can trigger self-aggregation in green algae into bioflocs and stimulate the secretion of specific proteins, behaviors that are likely crucial for forming stable symbiotic consortia with archaea as well [25] [26]. This suggests archaeal signals may similarly modulate algal morphology and physiology.

Secondary Messengers and Growth Regulators: Small signaling molecules like cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) coordinate behaviors such as biofilm formation in prokaryotes [26]. In symbiotic systems, c-di-GMP can upregulate algal exopolysaccharide (EPS) production, promoting aggregate formation. Furthermore, archaea may produce or mimic plant-growth regulators like indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a type of auxin. In modeled systems, IAA signaling has been shown to significantly enhance algal lipid accumulation, a key metabolite for biofuel production [26]. Disruption of this signaling can reduce lipid yields by up to 70%, underscoring its importance [26].

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated signaling pathways that facilitate the establishment of a stable algae-archaea symbiotic consortium.

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is a powerful evolutionary mechanism enabling algae to acquire novel traits directly from associated prokaryotes, including archaea, without sexual reproduction. This process can rapidly expand algal metabolic capabilities and enhance their adaptability to stressful environments.

Mechanisms and Evidence: HGT involves the lateral movement of genetic material between distantly related organisms. In intertidal algae, this is often facilitated by transposable elements (TEs). A chromosome-level genome analysis of the red alga Pyropia haitanensis identified 286 HGT-derived genes, 251 of which were associated with TEs, highlighting the role of TEs in the integration and stabilization of foreign genes [27]. Donors of these genes were primarily bacterial phyla like Pseudomonas and Actinobacteria, which are dominant members of its symbiotic community, though archaeal donors are also plausible [27].

Functionally Significant Transfers: Acquired genes often confer immediate adaptive advantages. In Pyropia haitanensis, two HGT-derived genes, sirohydrochlorin ferrochelatase and peptide-methionine (R)-S-oxide reductase, were linked via bulked segregant analysis (BSA) to the alga's tolerance to heat stress [27]. Similarly, the extremophilic red alga Galdieria sulphuraria acquired numerous genes from archaea and bacteria, enabling it to survive in hot, acidic, and metal-rich springs and utilize over 50 different carbon sources [25]. These findings position HGT as a critical driver in the ecological expansion and diversification of algae.

Table 2: Experimentally Validated HGT Genes in Algae and Their Putative Functions

| Algal Species | Acquired Gene / Enzyme | Putative Donor | Function in Alga | Adaptive Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyropia haitanensis [27] | Sirohydrochlorin ferrochelate | Bacteria/Archaea | Heme biosynthesis | Enhanced heat tolerance |

| Pyropia haitanensis [27] | Peptide-methionine (R)-S-oxide reductase | Bacteria/Archaea | Repair of oxidized proteins | Enhanced heat tolerance |

| Galdieria sulphuraria [25] | >75 genes (various metabolic enzymes) | Bacteria and Archaea | Diverse substrate metabolism | Survival in extreme environments (heat, metals, acidity) |

| Pyropia yezoensis [27] | Superoxide dismutase (SOD), Peroxidase | Prokaryotes | Oxidative stress response | Detoxification of reactive oxygen species |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Establishing a Model Symbiosis System

Objective: To construct and maintain a stable co-culture of Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Bacillus subtilis as a model for investigating symbiotic mechanisms, with methodologies applicable to algae-archaea systems [9].

Strains and Cultivation:

- Obtain Chlorella pyrenoidosa (e.g., FACHB-9) and Bacillus subtilis (e.g., 1.7740) from culture collections.

- Pre-culture C. pyrenoidosa axenically in 300 mL of BG-11 medium in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks.

- Pre-culture B. subtilis in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth.

- Incubate both cultures at 28°C under a continuous light intensity of 60–300 μmol/m²/s with a 12:12 light-dark cycle for 5-7 days [9].

Inoculation and Co-culture:

- Harvest algal and bacterial cells during their late exponential growth phase via centrifugation (e.g., 5000 x g for 10 min).

- Wash pellets with sterile physiological saline to remove residual medium.

- Mix the washed cell pellets in a defined ratio (e.g., 1:1 cell concentration ratio) and re-suspend in fresh BG-11 medium [9].

- Maintain the co-culture under the conditions described in step 1.

Growth Monitoring:

- Chlorophyll a Measurement: Monitor algal growth every 24-48 hours. Extract chlorophyll a by harvesting cells, extracting with 90% methanol, and measuring absorbance at 665 and 652 nm. Calculate concentration using standard formulas [9].

- Cell Dry Weight: Determine biomass production by filtering a known culture volume through a pre-weighed dry filter, drying at 105°C to constant weight, and measuring the mass increase [9].

Protocol 2: Identifying Horizontally Transferred Genes

Objective: To identify and validate genes of putative archaeal origin in an algal genome, using Pyropia haitanensis as a case study [27].

High-Quality Genome Assembly:

- Sequencing: Isolate high-molecular-weight DNA from a host organism. Sequence using long-read technologies (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio HiFi) to achieve >100x coverage. Perform complementary short-read Illumina sequencing for polishing.

- Symbiont Depletion: Employ nuclei isolation or flow cytometry to minimize bacterial/archaeal DNA contamination prior to sequencing.

- Assembly & Chromosome Scaffolding: Assemble sequences into contigs. Use Hi-C proximity ligation data to scaffold contigs into chromosome-level assemblies, distinguishing host chromosomes from contaminant sequences based on interaction matrices [27].

Bioinformatic HGT Prediction:

- Taxonomic Screening: Annotate the assembled genome and compare all predicted protein sequences against comprehensive non-redundant (NR) databases using BLAST. Flag genes with a best hit to a non-phylogenetically related group (e.g., algal gene with top hit to archaea).

- Phylogenetic Confirmation: For candidate HGT genes, perform multiple sequence alignments and construct maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees. A gene is strongly supported as horizontally acquired if the algal sequence is nested within a clade of archaeal orthologs to the exclusion of other eukaryotic sequences [27].

- Analysis of Flanking Regions: Investigate the genomic context of candidate genes for the presence of transposable elements (TEs), which are often associated with HGT events [27].

Phenotypic Validation (e.g., BSA for Stress Tolerance):

- Population Construction: Cross heat-tolerant and heat-sensitive algal strains to generate a segregating F2 population.

- Bulk Construction: Pool tissue from ~50 extremely heat-tolerant F2 individuals to form the "high" bulk, and from ~50 extremely sensitive individuals to form the "low" bulk.

- Genotyping and Analysis: Sequence the two bulks and the parent strains. Identify genomic regions and specific HGT candidate genes where the allele frequency significantly diverges between the high and low bulks, linking the gene to the heat tolerance trait [27].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for identifying horizontally transferred genes, from initial genome sequencing to phenotypic validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Algal-Symbiont Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BG-11 Medium [9] | Defined freshwater medium for cyanobacteria and microalgae cultivation. | Axenic pre-culture of Chlorella pyrenoidosa [9]. |

| Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) Broth [9] | Nutrient-rich general-purpose medium for growing a wide variety of fastidious bacteria. | Cultivation of Bacillus subtilis and other heterotrophic symbionts [9]. |

| F/2 Medium | Defined seawater medium for marine phytoplankton cultivation. | Cultivation of marine algae like Nannochloropsis or diatoms. |

| Polyethylene Coated Carbon (PEC) Particles | Buoyant carrier particles for biofilm formation in inverse fluidized bed bioreactors (IFBBR). | Creating stable algal-bacterial/archaeal biofilms for wastewater treatment studies [29]. |

| Nuclei Isolation/Percoll Gradient Kits | Isolation of nuclei from algal cells to reduce contaminating symbiont DNA during host genome sequencing. | Preparation of high-molecular-weight DNA for symbiont-free genome assembly [27]. |

| Hi-C Sequencing Kit | Capturing chromatin conformation data for chromosome-level scaffolding. | Distinguishing host algal chromosomes from contaminant sequences in genome assembly [27]. |

| AHL Standards (e.g., C6-HSL, 3OC6-HSL) | Pure quorum-sensing signal molecules for experimental treatment. | Investigating the effect of prokaryotic signals on algal gene expression and morphology [25] [26]. |

| Methanol (90%) | Solvent for chlorophyll a extraction from algal biomass. | Quantification of algal growth in co-culture experiments [9]. |

| 4-Nitropyrazole | 4-Nitro-1H-pyrazole | High Purity | For Research Use | High-purity 4-Nitro-1H-pyrazole, a key heterocyclic building block for medicinal chemistry & life science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| myo-Inositol,hexaacetate | (2,3,4,5,6-Pentaacetyloxycyclohexyl) Acetate | (2,3,4,5,6-Pentaacetyloxycyclohexyl) acetate for research. A key biochemical building block. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Archaea, one of the three domains of life, play indispensable roles in global biogeochemical cycles, particularly in carbon fixation and methanogenesis. These microorganisms inhabit diverse ecosystems, from extreme environments to moderate habitats including the open ocean, soils, and animal digestive systems. Carbon fixation and methanogenesis are two critical processes mediated by archaea that significantly impact carbon cycling and atmospheric composition. This review examines the mechanisms of these processes, their ecological significance, and their interplay within algae-archaea symbiotic relationships, which represent an emerging frontier in environmental microbiology. Archaea contribute substantially to global carbon cycling through their unique metabolic pathways, with methanogenic archaea (methanogens) alone contributing approximately 0.2 gigatons of methane annually from natural sources like wetlands [30]. Understanding these processes is crucial for predicting climate change impacts and developing biotechnological applications.

Carbon Fixation Pathways in Archaea

Carbon fixation, the process of converting inorganic carbon (COâ‚‚) into organic compounds, is performed by various archaeal lineages through multiple pathways. These pathways enable archaea to function as primary producers in diverse ecosystems, including those where they form symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic organisms.

Key Carbon Fixation Pathways

Archaea employ several distinct pathways for carbon fixation, each with unique biochemical mechanisms and energy requirements:

3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Cycle: Primarily found in thermophilic archaea such as those from the orders Sulfolobales and Thermoproteales. This pathway operates effectively under high-temperature conditions and involves the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to form malonyl-CoA, which is then converted to 4-hydroxybutyrate before being split into two molecules of acetyl-CoA.

Dicarboxylate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Cycle: Utilized by anaerobic archaea including Ignicoccus species and other thermophilic anaerobes. This cycle begins with the carboxylation of succinyl-CoA to form oxaloacetate, proceeds through dicarboxylic acids, and utilizes 4-hydroxybutyrate as a key intermediate.

Reductive Acetyl-CoA Pathway (Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway): Employed by methanogenic archaea for both carbon fixation and energy generation. This pathway directly reduces COâ‚‚ to a methyl group, which is then combined with CO and CoA to form acetyl-CoA.

The table below summarizes the distribution and key features of these pathways:

Table 1: Carbon Fixation Pathways in Archaea

| Pathway | Representative Archaeal Groups | Key Enzymes | Habitat Preferences |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Cycle | Sulfolobales, Thermoproteales | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, 4-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase | Terrestrial hot springs, acidic environments |

| Dicarboxylate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Cycle | Ignicoccus, Thermoproteales | Pyruvate synthase, 4-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase | Marine hydrothermal vents, anaerobic sediments |

| Reductive Acetyl-CoA Pathway | Methanogens, Methanobacteriales | Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, Formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase | Anaerobic environments (ruminant guts, wetlands) |

Ecological Significance of Archaeal Carbon Fixation

Archaea contribute significantly to carbon fixation in various ecosystems. In marine environments, Thaumarchaeota (now classified as Nitrososphaeria) are among the most abundant microorganisms and play crucial roles in both carbon and nitrogen cycling [1]. These organisms fix carbon while simultaneously oxidizing ammonia, coupling carbon and nitrogen cycles in the ocean. The organic carbon produced by archaea supports higher trophic levels and contributes to carbon sequestration in marine sediments.

In extreme environments such as hot springs and deep-sea hydrothermal vents, archaeal carbon fixation represents the foundation of the food web. The unique enzymes and pathways employed by these extremophilic archaea have attracted significant biotechnological interest for industrial applications requiring high-temperature or high-pressure conditions.

Methanogenesis: Mechanisms and Environmental Impact

Methanogenesis is a specialized form of anaerobic respiration that generates methane as the final metabolic product. This process is exclusively performed by methanogenic archaea and represents the terminal step in organic matter decomposition in anaerobic environments.

Biochemical Pathways of Methanogenesis

Methanogenic archaea employ three primary metabolic pathways for methane production, each utilizing different substrates:

Hydrogenotrophic Methanogenesis: Uses hydrogen to reduce carbon dioxide to methane according to the stoichiometry: 4H₂ + CO₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O. This is the most prevalent pathway among characterized methanogen strains [31] [32].

Methylotrophic Methanogenesis: Involves the conversion of methylated compounds such as methanol, methylamines, and methyl sulfides to methane. Some methylotrophic methanogens require Hâ‚‚ as an electron donor, while others can perform Hâ‚‚-independent methanol reduction [31].

Acetoclastic Methanogenesis: Splits acetate into methane and carbon dioxide: CH₃COOH → CH₄ + CO₂. This pathway is less common among host-associated methanogens compared to environmental strains [31].

The key enzyme in all methanogenesis pathways is methyl-coenzyme M reductase (Mcr), which catalyzes the final step of methyl group reduction to methane [30]. This enzyme is unique to methanogenic archaea and is often used as a molecular marker for detecting methanogens in environmental samples.

Table 2: Methanogenesis Pathways and Their Characteristics

| Pathway | Primary Substrates | Representative Genera | Energy Yield | Environmental Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogenotrophic | Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚, Formate | Methanobrevibacter, Methanobacterium | ~1 ATP/CHâ‚„ [32] | Most common in host-associated systems |

| Methylotrophic | Methanol, Methylamines, Methyl sulfides | Methanosphaera, Methanomassiliicoccales | Variable | Moderate, dependent on substrate availability |

| Acetoclastic | Acetate | Methanosarcina | ~1 ATP/CHâ‚„ | Less common in hosts, dominant in sediments |

Environmental Significance of Methanogenesis

Methanogenesis plays a crucial role in global carbon cycling, with methanogenic archaea contributing significantly to atmospheric methane concentrations. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with approximately 30 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period [30]. Current atmospheric methane concentrations have reached record levels of approximately 1,896 parts per billion, with wetlands and other natural sources contributing roughly 0.2 gigatons annually [30].

The process of methanogenesis also creates a concerning climate feedback loop: rising global temperatures increase the activity and abundance of methanogens in environments like thawing permafrost, leading to additional methane emissions that further accelerate warming [30]. In northern wetlands, for example, permafrost thaw initially favors hydrogenotrophic methanogens, but as thawing progresses, acetoclastic methanogens become dominant, potentially increasing methane production efficiency [30].

The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic pathways and environmental significance of methanogenesis:

Figure 1: Methanogenesis Pathways and Their Environmental Significance

Archaea in Symbiotic Relationships

Archaea form diverse symbiotic relationships with eukaryotic hosts, particularly algae, which influence biogeochemical cycles across various ecosystems. These symbiotic interactions represent a significant yet understudied aspect of microbial ecology.

Algae-Archaea Symbioses

Algae and archaea coexist in diverse aquatic ecosystems, where their interactions play significant roles in ecological functions and biogeochemical cycles [1]. Macroalgal surfaces provide ideal habitats for archaeal colonization due to high organic carbon content and abundant oxygen. The associated microbial communities, including archaea, together with the algal host form a functional unity termed a "holobiont" [1].

Metagenomic studies have revealed that macroalgae-associated archaea primarily belong to Nitrososphaeria (formerly Thaumarchaeota) and methanogenic Euryarchaeota [1]. For instance, ammonium-oxidizing archaea from the Nitrososphaeria class have been identified on macroalgal species such as Osmundaria volubilis, Phyllophora crispa, and Laminaria rodriguezii [1]. Methanogenic Euryarchaeota, including families such as Methanomicrobiaceae, Methanosarcinaceae, and Methanococcaceae, have been detected associated with Sargassum and Ulva prolifera [1].

The interaction between algae and archaea influences the cycling of essential elements including carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, with potential impacts on atmospheric pools of greenhouse gases such as COâ‚‚ and CHâ‚„ [1]. Archaea may benefit from dissolved organic matter released by algae, while potentially providing growth-promoting factors to their algal hosts, though the exact mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Animal-Associated Methanogens

Methanogenic archaea form essential symbiotic relationships within the gastrointestinal tracts of diverse animal species, including ruminants, insects, and humans. In ruminants like cattle and sheep, methanogens participate in syntrophic interactions with bacterial and fungal partners, consuming hydrogen and other fermentation products that would otherwise inhibit microbial digestion [31]. This process, known as interspecies hydrogen transfer, enhances the efficiency of cellulose degradation while generating methane as a waste product [31].

The table below summarizes key archaeal symbionts in different hosts:

Table 3: Archaea in Symbiotic Associations with Eukaryotic Hosts

| Host Organism | Associated Archaea | Type of Interaction | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruminants (cattle, sheep) | Methanobrevibacter, Methanosphaera | Syntrophic | Hydrogen consumption, enhances fermentation efficiency |

| Termites, Cockroaches | Methanobrevibacter spp. | Commensal/Mutualistic | Lignocellulose digestion, methane production |

| Humans | Methanobrevibacter smithii, Methanosphaera stadtmanae | Commensal | Hydrogen removal, potential role in energy harvest |

| Marine Sponges | Cenarchaeum symbiosum, other Crenarchaeota | Symbiotic | Potential involvement in nitrogen metabolism |

| Macroalgae | Nitrososphaeria, Methanogenic Euryarchaeota | Epiphytic | Nitrogen cycling, methane production |

In the human gut, methanogens comprise up to 10% of the anaerobic microbial community in some individuals, with Methanobrevibacter smithii being the most prevalent species [33]. These archaea remove hydrogen through methanogenesis, potentially affecting host energy harvest and having been correlated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis, though causal relationships remain uncertain [33] [34].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Studying archaeal involvement in carbon fixation and methanogenesis requires specialized methodologies due to their unique physiological properties and frequently anaerobic growth requirements.

Cultivation Techniques

Cultivating methanogenic archaea requires strict anaerobic conditions and specialized growth media. The following protocol outlines standard cultivation methods for methanogens:

Table 4: Standardized Culture Medium for Methanogen Growth

| Component | Concentration | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution A | 150 mL | Mineral base | KH₂PO₄, (NH₄)₂SO₄, NaCl, MgSO₄·7H₂O, CaCl₂·2H₂O |

| Solution B | 150 mL | Phosphate buffer | Kâ‚‚HPOâ‚„ |

| NaHCO₃ | 12 g/L | Carbon source & buffer | |

| Vitamin Supplement | 1 mL | Essential cofactors | Supplement with cyanocobalamin |

| Trace Element Solution | 10 mL | Metal requirements | Mn, Ni, Mo, Fe, Co, Se, V, Zn, Cu |

| Resazurin | 1 mL (0.1% w/v) | Redox indicator | Pink indicates oxygen contamination |

| L-cysteine-HCl | 1 g/L | Reducing agent | Maintains anaerobic conditions |

| Substrate Supplements | Variable | Energy source | Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ (80/20), methanol, acetate, formate |

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare base medium by combining Solutions A and B with NaHCO₃ in MilliQ H₂O to 1L total volume.

- Boil vigorously to drive off oxygen, then cool under COâ‚‚ atmosphere.

- Aliquot under 80/20 Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ gas mixture before autoclaving.

- After autoclaving, add filter-sterilized vitamin solutions and specific substrates (methanol, formate, acetate) based on methanogen requirements.

- Inoculate with archaeal culture and incubate at appropriate temperature (typically 35-39°C for mesophilic strains) without shaking [34].

Molecular and Genomic Approaches

Genomic analysis has revealed significant insights into methanogen metabolism and adaptability. Comparative genomics of four diverse methanogen species (Methanobacterium bryantii, Methanosarcina spelaei, Methanosphaera cuniculi, and Methanocorpusculum parvum) revealed a genomic trend towards energy conservation, with distinct membrane proteins and transporters supporting different energy conservation strategies [34].

Epigenetic studies using Nanopore sequencing have uncovered DNA modification patterns in methanogens that may play roles in gene regulation and self-identification [35]. Additionally, genomic analyses have identified pervasive nucleotide tandem repeats in methanogen genomes that may contribute to their ecological adaptability through phase variation mechanisms [35].

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for studying archaeal functions in biogeochemical cycling:

Figure 2: Research Workflow for Studying Archaeal Biogeochemical Functions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Archaeal Biogeochemical Processes

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Culture Systems | Anaerobic chambers, sealed serum bottles | Creating oxygen-free environment for growth | Use resazurin (0.1% w/v) as oxygen indicator [34] |

| Reducing Agents | L-cysteine-HCl, sodium sulfide | Maintaining low redox potential | Critical for methanogen viability |

| Trace Element Solutions | MnCl₂·4H₂O, NiCl₂·6H₂O, NaMoO₄·2H₂O | Providing essential micronutrients | Nickel particularly important for hydrogenases |

| Methanogen Substrates | Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ mixture, methanol, sodium formate, sodium acetate | Energy and carbon sources | Specific to methanogenic pathway |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Metagenomic DNA extraction kits | Community analysis without cultivation | Must include protocols for tough cell walls |

| Epigenetic Tools | Nanopore sequencing | Detecting DNA modifications | Reveals epigenetic regulation [35] |

| Stable Isotopes | ¹³C-labeled bicarbonate, ¹³C-acetate | Tracing carbon fixation pathways | Enables SIP (Stable Isotope Probing) |

| Boc-N-Ethylglycine | BOC-N-ethylglycine | High-Quality Building Block | BOC-N-ethylglycine is a key N-alkylated amino acid derivative for peptide synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Imiclopazine | Imiclopazine dihydrochloride | High Purity | RUO | Imiclopazine dihydrochloride for research. A phenothiazine derivative for neuropsychiatric & pharmacological studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Implications and Future Directions